| A.W.38 Whitley | |

|---|---|

| |

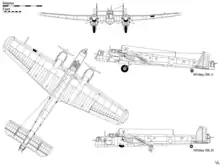

| Whitley Mk.V | |

| Role | Heavy bomber, night bomber |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft |

| Designer | John Lloyd |

| First flight | 17 March 1936 |

| Introduction | 1937 |

| Retired | 1945 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary user | Royal Air Force |

| Number built | 1,814[1] |

| Developed from | Armstrong Whitworth AW.23 |

The Armstrong Whitworth A.W.38 Whitley was a British medium bomber aircraft of the 1930s. It was one of three twin-engined, front line medium bomber types that were in service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) at the outbreak of the Second World War. Alongside the Vickers Wellington and the Handley Page Hampden, the Whitley was developed during the mid-1930s according to Air Ministry Specification B.3/34, which it was subsequently selected to meet. In 1937, the Whitley formally entered into RAF squadron service; it was the first of the three medium bombers to be introduced.

Following the outbreak of war in September 1939, the Whitley participated in the first RAF bombing raid upon German territory and remained an integral part of the early British bomber offensive. In 1942 it was superseded as a bomber by the larger four-engined "heavies" such as the Avro Lancaster.[2] Its front-line service included maritime reconnaissance with Coastal Command and the second line roles of glider-tug, trainer and transport aircraft. The type was also procured by British Overseas Airways Corporation as a civilian freighter aircraft. The aircraft was named after Whitley, a suburb of Coventry, home of Armstrong Whitworth's Whitley plant.

Development

Origins

In July 1934, the Air Ministry issued Specification B.3/34, seeking a heavy night bomber/troop transport to replace the Handley Page Heyford biplane bomber.[3] This combination bomber/transport was part of the RAF's concept of fighting wars in distant British Empire locations, where the aircraft would fly into the theatre of action carrying troops and then provide air support.

John Lloyd, the Chief Designer of Armstrong Whitworth Aircraft, chose to respond to the specification with the AW.38 design, which later was given the name Whitley after the location of Armstrong Whitworth's main factory. The design of the AW.38 was a development of the Armstrong Whitworth AW.23 bomber-transport design that had lost to the Bristol Bombay for the earlier Specification C.26/31.[3]

Lloyd selected the Armstrong Siddeley Tiger IX radial engine to power the Whitley, which was capable of generating 795 hp (593 kW).[3] One of the novel features of the Whitley's design was the adoption of a three-bladed two-position variable-pitch propeller built by de Havilland; the Whitley was the first aircraft to fly with such an arrangement.[3]

As Lloyd was unfamiliar with the use of flaps on a large heavy monoplane, they were initially omitted from the design. To compensate, the mid-set wings were set at a high angle of incidence (8.5°) to confer good take-off and landing performance.[4] Flaps were included late in the design stage, the wing remained unaltered; as a result, the Whitley flew with a pronounced nose-down attitude when at cruising speed, resulting in considerable drag.[4][5]

The Whitley holds the distinction of having been the first RAF aircraft with a semi-monocoque fuselage, which was built using a slab-sided structure to ease production.[2] This replaced the tubular construction method traditionally employed by Armstrong Whitworth, who instead constructed the airframe from light-alloy rolled sections, pressings and corrugated sheets.[3] According to aviation author Philip Moyes, the decision to adopt the semi-monocoque fuselage was a significant advance in design; many Whitleys surviving severe damage on operations.[3]

In June 1935, owing to the urgent need to replace biplane heavy bombers then in service with the RAF, it was agreed to produce an initial 80 aircraft, 40 being of an early Whitley Mk I standard and the other 40 being more advanced Whitley Mk IIs.[4] Production was initially at three factories in Coventry; fuselages and detailed components were fabricated at Whitley Abbey, panel-beating and much of the detailed work at the former Coventry Ordnance Works factory, while wing fabrication and final assembly took placed at Baginton Aerodrome.[4] During 1935 and 1936, various contracts were placed for the type; the Whitley was ordered "off the drawing board" - prior to the first flights of any of the prototypes.[4]

On 17 March 1936, the first prototype Whitley Mk I, K4586, conducted its maiden flight from Baginton Aerodrome, piloted by Armstrong Whitworth Chief Test Pilot Alan Campbell-Orde.[6] K4586 was powered by a pair of 795 hp (593 kW) Armstrong Siddeley Tiger IX 14-cylinder air-cooled aircraft radial engines. The second prototype, K4587, was furnished with a pair of more powerful medium-supercharged Tiger XI engines.[7][6] The prototypes differed little from the initial production standard aircraft; a total of 34 production Whitley Mk I were completed.[6]

Further development

After the first 34 aircraft had been completed, the engines were replaced with the more reliable two-speed-supercharged Tiger VIIIs. K7243, the 27th production Whitley, is believed to have served as a prototype following modifications.[6] The resulting aircraft was designated as the Whitley Mk II. A total of 46 production aircraft were completed to the Whitley Mk II standard.[6] One Whitley Mk II, K7243, was used as a test bed for the 1,200 hp (890 kW) 21-cylinder radial Armstrong Siddeley Deerhound engine; on 6 January 1939, K7243 made its first flight with the Deerhound.[8][9] Another Whitley Mk I, K7208, was modified to operate with a higher (33,500 lb (15,200 kg)) gross weight.[10]

K7211, the 29th production Whitley, served as the prototype for a further advanced variant of the aircraft, the Whitley Mk III.[6] The Whitley Mk III featured numerous improvements, such as the replacement of the manually operated nose turret with a single powered Nash & Thompson turret and a powered retractable twin-gun ventral "dustbin" turret. The ventral turret was hydraulically-powered but proved to be hard to operate and added considerable drag, thus the Whitley Mk III was the only variant with it.[6] Other changes included increased dihedral of the outer wing panels, superior navigational provision and the installation of new bomb racks.[11] A total of 80 Whitley Mk III aircraft were manufactured.[6]

While the Tiger VIII engine used in the Whitley Mks II and III was more reliable than those used in early aircraft, the Whitley was re-engined with Rolls-Royce Merlin engines in 1938, giving rise to the Whitley Mk IV.[12] Three Whitley Mk I aircraft, K7208, K7209 and K7211, were initially re-engined to serve as prototypes. The new engines are credited with producing greatly improved performance.[2][12] Other changes made included the replacement of the manually operated tail and retractable ventral turrets with a Nash & Thompson powered tail turret equipped with four .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns, the increasing of fuel tankage capacity, including two additional fuel tanks in the wing.[12] A total of 40 Whitley Mk IV and Whitley Mk IVA, a sub-variant featuring more powerful models of the Merlin engine, were completed.[12]

The decision was made to introduce a series of other minor improvements to produce the Whitley Mk V. These included the modification of the tail fins and rudders, the fitting of leading edge de-icers, further fuel capacity increases, a smaller D/F loop in a streamlined fairing being adopted, and the extension of the rear fuselage by 15 in (381 mm) to improve the rear-gunner's field of fire.[13] The Whitley Mk V was by far the most numerous version of the aircraft, with 1,466 built until production ended in June 1943.[2][13]

The Whitley Mk VII was the final variant to be built. Unlike the other variants, it was developed for service with RAF Coastal Command and was thus furnished for maritime reconnaissance rather than as a general purpose bomber.[13] A Whitley Mk V, P3949 acted as a prototype for this variant. A total of 146 Whitley Mk VIIs were produced, additional Whitley Mk V aircraft being converted to the standard.[13] It had a sixth crew member to operate the new ASV Mk II radar system along with an increased fuel capacity for long endurance anti-shipping missions.[14] Some Whitley Mk VII were later converted as trainer aircraft, featuring additional seating and instrumentation for flight engineers.[10]

Early marks of the Whitley featured bomb bay doors, fitted on the fuselage and wing bays, that were held shut by bungee cords; during bombing operations, these were opened by the weight of the bombs as they fell on them and closed again by the bungee cord.[4][5] The short and unpredictable delay for the doors to open led to highly inaccurate bombing. The Mk.III introduced hydraulic doors which greatly improved bombing accuracy. To aim bombs, the bomb aimer opened a hatch in the nose of the aircraft, which extended the bomb sight out of the fuselage but the Mk IV replaced this hatch with a slightly extended transparent plexiglas panel, improving crew comfort.[12][15]

Design

The Armstrong Whitworth Whitley was a twin-engined heavy bomber, initially being powered by a pair of 795 hp (593 kW). Armstrong Siddeley Tiger IX radial engines.[16] More advanced models of the Tiger engine equipped some of the later variants of the Whitley; starting with the Whitley Mk IV variant, the Tigers were replaced by a pair of 1,030 hp (770 kW) Rolls-Royce Merlin IV V12 engines.[11] According to Moyes, the adoption of the Merlin engine gave the Whitley a considerable boost in performance.[12]

The Whitley had a crew of five: a pilot, co-pilot/navigator, a bomb aimer, a wireless operator and a rear gunner. The pilot and second pilot/navigator sat side by side in the cockpit, with the wireless operator further back. The navigator, his seat mounted on rails and able to pivot, slid backwards and rotated to the left to use the chart table behind him after take-off.[15] The bomb aimer position was in the nose with a gun turret located directly above. The fuselage aft of the wireless operator was divided horizontally by the bomb bay; behind the bomb bay was the main entrance and aft of that the rear turret.[15] The bombs were stowed in two bomb bays housed within the fuselage, along with a further 14 smaller cells in the wing.[4] Other sources state there were 16 "cells", two groups of two in the fuselage and four groups of three in the wings, plus two smaller cells for parachute flares in the rear fuselage.[15] Bomb racks capable of holding larger bombs were installed on the Whitley Mk III variant.[6]

The early examples had a nose turret and rear turret, both being manually operated with one Vickers 0.303 machine gun apiece. On the Whitley Mk III this arrangement was substantially revised: a new retractable ventral 'dustbin' position was installed mounting twin .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine-guns and the nose turret was also upgraded to a Nash & Thompson power-operated turret.[6] On the Whitley Mk IV, the tail and ventral turrets were replaced with a Nash & Thompson power-operated tail turret mounting four Browning .303 machine guns; upon the adoption of this turret arrangement, the Whitley became the most powerfully armed bomber in the world against attacks from the rear.[12]

The fuselage comprised three sections, with the main frames being riveted with the skin and the intermediate sections being riveted to the inside flanges of the longitudinal stringers.[3] Extensive use of Alclad sheeting was made. Fuel was carried in three tanks, a pair of 182 imp gal (830 L) tanks in the leading edge of each outer wing and one 155 imp gal (700 L) tank in the roof of the fuselage, over the spar center section; two auxiliary fuel tanks could be installed in the front fuselage bomb bay compartment. The inner leading edges contained the oil tanks, which doubled as radiant oil coolers.[4][15] To ease production, a deliberate effort was made to reduce component count and standardise parts.[3] The fuselage proved to be robust enough to withstand severe damage.[4]

The Whitley featured a large rectangular-shaped wing; its appearance led to the aircraft receiving the nickname "the flying barn door".[4] Like the fuselage, the wings were formed from three sections, being built up around a large box spar with the leading and trailing edges being fixed onto the spar at each rib point.[17] The forward surfaces of the wings were composed of flush-riveted, smooth and unstressed metal sheeting; the rear 2/3rds aft of the box spar to the trailing edge, as well as the ailerons and split flaps was fabric covered.[15][17] The inner structure of the split flaps was composed of duralumin and ran between the ailerons and the fuselage, being set at a 15–20 degree position for taking off and at a 60 degree position during landing.[4] The tailplanes employed a similar construction to that of the wings, the fins being braced to the fuselage using metal struts; the elevators and rudders incorporated servo-balancing trim tabs.[4]

Operational history

Military service

On 9 March 1937, the Whitley Mk I began entering squadron service with No. 10 Squadron of the RAF, replacing their Handley Page Heyford biplanes.[18][19] In January 1938, the Whitley Mk II first entered squadron service with No. 58 Squadron and in August 1938, the Whitley Mk III first entered service with No. 51 Squadron.[19] In May 1939, the Whitley Mk IV first entered service with No. 10 Squadron and in August 1939, the Whitley Mk IVA first entered service with No. 78 Squadron.[19] By the outbreak of the Second World War, seven squadrons were operational, the majority of these flying Whitley III or IV aircraft, while the Whitley V had only just been introduced to service; 196 Whitleys were on charge with the RAF.[18][19][20]

At the start of the war, 4 Group, equipped with the Whitley, was the only trained night bomber force in the world.[19] Alongside the Handley Page Hampden and the Vickers Wellington, the Whitley bore the brunt of the early fighting and saw action during the first night of the war, when they dropped propaganda leaflets over Germany.[21] The propaganda flight made the Whitley the first aircraft of RAF Bomber Command to penetrate into Germany.[19] Further propaganda flights would travel as far as Berlin, Prague, and Warsaw.[22] On the night of 19/20 March 1940, in conjunction with Hampdens, the Whitley conducted the first bombing raid on German soil, attacking the Hörnum seaplane base on the Island of Sylt.[2][23] Following the Hörnum raid, Whitleys routinely patrolled the Frisian Islands, targeting shipping and seaplane activity.[19]

Unlike the Hampden and Wellington, which had met Specification B.9/32 for a day bomber, the Whitley was always intended for night operations and escaped the early heavy losses received during daylight raids carried out upon German shipping.[3] As the oldest of the three bombers, the Whitley was obsolete by the start of the war, yet over 1,000 more aircraft were produced before a suitable replacement was found. A particular problem with the radar-equipped Mk VII, with the addition of the drag-producing aerials, was that it could not maintain altitude on one engine. Whitleys flew a total of 8,996 operations with Bomber Command, dropped 9,845 tons (8,931 tonnes) of bombs and 269 aircraft were lost in action.[24]

On the night of 11/12 June 1940, the Whitley carried out Operation Haddock, the first RAF bombing raid on Italy, only a few hours after Italy's declaration of war; the Whitleys bombed Turin and Genoa, reaching northern Italy via a refuelling stop in the Channel Islands.[21][23] Many leading World War II bomber pilots of the RAF flew Whitleys at some point in their career, including Don Bennett, James Tait, and Leonard Cheshire.[25]

On the night of 10/11 February 1941, six Whitley Vs of 51 Squadron led by Tait took part in Operation Colossus, the first airborne operation undertaken by the British military, delivering paratroops to attack the Tragino Aqueduct in southern Italy. The Whitley was not always popular with paratroopers as they exited via a bin like chute in the floor. If this was not timed correctly the airflow would drag the paratrooper out resulting in nasty injuries to the face against the lip of the chute known as a Whitley kiss.

On the night of 29/30 April 1942 No. 58 Squadron, flying Whitleys, bombed the Port of Ostend in Belgium. This was the last operational mission by a Whitley-equipped bomber squadron.[26] In late 1942, the Whitley was retired from service as a frontline aircraft for bomber squadrons and was shifted to other roles. The type continued to operate delivering supplies and agents in the Special Duties squadrons (138 and 161) until December 1942, as well as serving as a transport for troops and freight, a carrier for paratroopers and a tow aircraft for gliders.[27] In 1940, the Whitley had been selected as the standard paratroop transport; in this role, the ventral turret aperture was commonly modified to be used for the egress of paratroopers.[26] No. 100 Group RAF used Whitleys to carry radar and electronic counter-measures. In February 1942, Whitleys were used to carry the paratroopers who participated in the Bruneval raid, code named Operation Biting, in which German radar components were captured from a German base on the coast of France.[27]

Long-range Coastal Command Mk VII variants were among the last Whitleys remaining in front-line service, remaining in service until early 1943.[26] The first U-boat kill attributed to the Whitley Mk VII was the sinking of the German submarine U-751 on 17 July 1942, which was achieved in combination with a Lancaster heavy bomber.[28][29] Having evaluated the Whitley in 1942, the Fleet Air Arm operated a number of modified ex-RAF Mk VIIs from 1944 to 1946, to train aircrew in Merlin engine management and fuel transfer procedures.[2]

Civilian service

In April/May 1942, the British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) operated 15 Whitley Mk V aircraft which had been converted into freighters. The conversion process involved the removal of all armaments, the turret recesses were faired over, additional fuel tanks were installed in the bomb bay, the interior of the fuselage was adapted for freight stowage, and at least one aircraft was fitted with an enlarged cargo door.[19] The type was typically used for night supply flights from Gibraltar to Malta; the route took seven hours, and would often require landing during Axis air attacks on their arrival at Malta.[30] Whitley freighters also flew the dangerous route between RAF Leuchars, Scotland and Stockholm, Sweden.[19] The Whitley consumed a disproportionally large quantity of fuel to carry a relatively small payload and there were other reasons making the type less than ideal, so, in August 1942, the type was replaced by the Lockheed Hudson and the 14 survivors were returned to the RAF.[19][30]

Variants

Following the two prototypes (K4586 and K4587), at the outbreak of the war the RAF had 207 Whitleys in service ranging from Mk I to Mk IV types, with improved versions following:

- Mk I

- A.W. Type 188. Powered by 795 hp (593 kW) Armstrong Siddeley Tiger IX air-cooled radial engines, 4 degrees of dihedral incorporated into each outer wing panel, with earlier aircraft being retrospectively modified: 34 built.[6]

- Mk II

- A.W. Type 197 (some Type 220). Powered by 920 hp (690 kW) two-speed supercharged Tiger VIII engines: 46 built.[6]

- Mk III

- A.W. Type 205. Powered by Tiger VIII engines, retractable "dustbin" ventral turret fitted aft of the wing root armed with two .303 in (7.7 mm) machine guns, hydraulically operated bomb bay doors and ability to carry larger bombs: 80 built.[6]

- Mk IV

- A.W. Type 209. Powered by 1,030 hp (770 kW) Rolls-Royce Merlin IV inline liquid-cooled engines, increased fuel capacity, extended bomb-aimer's transparency, manually operated tail and retractable ventral turrets replaced with a single Nash & Thompson powered tail turret equipped with four .303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns, produced from 1938: 33 built.[12]

- Mk IVA

- A.W. Type 210. Mk IV variant powered by 1,145 hp (854 kW) Merlin X engines made by fitting Merlin X engines on last Mk IV's on production line: seven built.[12]

- Mk V

- A.W. Type 207. The main wartime production version based on the Mk IV, modified straight-edged fins, leading edge de-icing, tail fuselage aft or empennage extended by 15 in (381 mm) to improve the tail gunner's field of fire.[2] First flew in December 1938, production ceased in June 1943: 1,466 built.[13]

- Mk VI

- Proposed Pratt & Whitney G.R.1830 Twin Wasp-powered version of Mk V in case of Merlin production shortfall: none built.[13]

- Mk VII

- A.W. Type 217. Designed for service with Coastal Command and carried a sixth crew member, capable of longer-range flights (2,300 mi/3,700 km compared to the early version's 1,250 mi/2,011 km)[2] having additional fuel tanks fitted in the bomb bay and fuselage, equipped with Air to Surface Vessel (ASV) radar for anti-shipping patrols with an additional four 'stickleback' dorsal radar masts and other antennae: 146 built.[14] Being heavier and less efficient with its aerials, this Mk could not maintain altitude on only one engine.

Operators

Military operators

- Royal Air Force

- No. 7 Squadron RAF between March 1938 and May 1939.

- No. 10 Squadron RAF between March 1937 and December 1941.

- No. 51 Squadron RAF between February 1938 and October 1942.

- No. 53 Squadron RAF between February 1943 and May 1943.

- No. 58 Squadron RAF between October 1937 and January 1943.

- No. 76 Squadron RAF between September 1939 and April 1940.

- No. 77 Squadron RAF between November 1938 and October 1942.

- No. 78 Squadron RAF between July 1937 and March 1942.

- No. 97 Squadron RAF between February 1939 and May 1940.

- No. 102 Squadron RAF between October 1938 and February 1942.

- No. 103 Squadron RAF between October 1940 and June 1942.

- No. 109 Squadron RAF operated only one aircraft (P5047).

- No. 115 Squadron RAF during 1938[31]

- No. 138 Squadron RAF between August 1941 and October 1942.

- No. 161 Squadron RAF between February 1942 and December 1942.

- No. 166 Squadron RAF between July 1938 and April 1940.

- No. 295 Squadron RAF between August 1942 and November 1943.

- No. 296 Squadron RAF between June 1943 and March 1943.

- No. 297 Squadron RAF between February 1942 and February 1944.

- No. 298 Squadron RAF between August 1942 and October 1942.

- No. 299 Squadron RAF between November 1943 and January 1944.

- No. 502 Squadron RAF between October 1940 and February 1943.

- No. 612 Squadron RAF between November 1940 and June 1943.

- No. 619 Squadron RAF between April 1943 and January 1944.

- No. 1419 Flight RAF

- No. 1473 Flight RAF

- No. 1478 Flight RAF

- No. 1481 Flight RAF

- No. 1484 Flight RAF

- No. 1485 Flight RAF

- No. 1486 Flight RAF

- No. 1 (Coastal) Operational Training Unit RAF

- No. 10 Operational Training Unit RAF

- No. 81 Operational Training Unit RAF

- No. 19 Operational Training Unit RAF

- No. 24 Operational Training Unit RAF

- No. 29 Operational Training Unit RAF

- No. 58 Operational Training Unit RAF

- No. 81 Operational Training Unit RAF

- No. 83 Operational Training Unit RAF

- Parachute Training School

- Parachute Section, 13 Maintenance Unit

- Fleet Air Arm

- 734 Naval Air Squadron operated Whitleys between February 1944 and February 1946.

Civil operators

Surviving aircraft

No complete aircraft of the 1,814 Whitleys produced remains. The Whitley Project is rebuilding an example from salvaged remains, and a fuselage section is displayed at the Midland Air Museum (MAM), whose site is adjacent to the airfield from where the Whitley's maiden flight took place.[32]

Specifications (Whitley Mk V)

.jpg.webp)

Data from The Whitley File[33]

General characteristics

- Crew: 5

- Length: 70 ft 6 in (21.49 m)

- Wingspan: 84 ft 0 in (25.60 m)

- Height: 15 ft 0 in (4.57 m)

- Wing area: 1,137 sq ft (105.6 m2)

- Empty weight: 19,300 lb (8,754 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 33,500 lb (15,195 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Rolls-Royce Merlin X liquid-cooled V12 engines, 1,145 hp (854 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 230 mph (370 km/h, 200 kn) at 16,400 ft (5,000 m)

- Range: 1,650 mi (2,660 km, 1,430 nmi)

- Ferry range: 2,400 mi (3,900 km, 2,100 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 26,000 ft (7,900 m)

- Rate of climb: 800 ft/min (4.1 m/s)

Armament

- Guns: ** 1 × .303 in (7.7 mm) Vickers K machine gun in nose turret

- 4 × .303 in Browning machine guns in tail turret

- Bombs: Up to 7,000 lb (3,175 kg) of bombs in the fuselage and 14 cells in the wings, typically including

- 12 × 250 lb (113 kg) and

- 2 × 500 lb (227 kg) bombs

- Bombs as heavy as 2,000 lb (907 kg) could be carried

See also

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

Notes

- ↑ Moyes 1967, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Crosby 2007, pp. 48–49.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Moyes 1967, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Moyes 1967, p. 4.

- 1 2 Gunston 1995

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Moyes 1967, p. 5.

- ↑ Swanborough 1997, p. 8..

- ↑ Roberts 1986, p. 8.

- ↑ Moyes 1967, pp. 10-11.

- 1 2 Moyes 1967, p. 10.

- 1 2 Moyes 1967, pp. 5-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Moyes 1967, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Moyes 1967, p. 7.

- 1 2 Moyes 1967, pp. 7, 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Flight 21 October 1937, p. 402.

- ↑ Moyes 1967, pp. 4-5.

- 1 2 Moyes 1967, pp. 3-4.

- 1 2 Mondey 1994, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Moyes 1967, p. 11.

- ↑ Thetford 1957, p. 27.

- 1 2 Green and Swanborough Air Enthusiast 1979, p. 22.

- ↑ Moyes 1967, pp. 11-12.

- 1 2 Moyes 1967, p. 12.

- ↑ Moyes 1976, p. 327.

- ↑ Moyes 1967, pp. 12-13.

- 1 2 3 Moyes 1967, p. 13.

- 1 2 Moyes 1967, pp. 13-14.

- ↑ U-boat.net/ "U-206." uboat.net. Retrieved: 8 August 2010.

- ↑ Uboat.net/ "U-751." uboat.net. Retrieved: 8 August 2010.

- 1 2 Jackson 1973, p. 325.

- ↑ Roberts 1978, p. 62.

- ↑ Roberts 1978, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Roberts 1986, p. 68

Bibliography

- "A Modern Heavy Bomber." Flight, 21 October 1937, pp. 396–402.

- Cheshire, Leonard. Leonard Cheshire V.C. Bomber Pilot. St. Albans, Herts, UK: Mayflower, 1975 (reprint of 1943 edition). ISBN 0-583-12541-7.

- Crosby, F. (2007). The World Encyclopedia of Bombers. London: Anness. ISBN 978-1-84477-511-8.

- Donald, David and Jon Lake. Encyclopedia of World Military Aircraft. London: AIRtime Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-880588-24-2.

- Green, William. Famous Bombers of the Second World War. London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1959, (third revised edition 1975). ISBN 0-356-08333-0.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. "Armstrong Whitworth's Willing Whitley" Air Enthusiast. No. 9, February–May 1979. Bromley, Kent, UK., pp. 10–25.

- Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. WW2 Aircraft Fact Files: RAF Bombers, Part 1. London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1979. ISBN 0-354-01230-4.

- Gunston, Bill (1995). Classic World War II Aircraft Cutaways. Botley: Osprey. ISBN 1-85532-526-8.

- Jackson, A. J. British Civil Aircraft since 1919 (Volume 1). London: Putnam & Company Ltd., 1973. ISBN 0-370-10006-9.

- Mason, Francis K. The British Bomber since 1914. London: Putnam Aeronautical Books, 1994. ISBN 0-85177-861-5.

- Mondey, David (1994). The Hamlyn Concise Guide to British Aircraft of World War II. London: Chancellor Press. ISBN 1-85152-668-4.

- Moyes, Philip J. R. The Armstrong Whitworth Whitley. Leatherhead, Surrey, UK: Profile Publications, 1967.

- Moyes, Philip J. R. (1964). Bomber Squadrons of the RAF and Their Aircraft (1976 rev. ed.). London: Macdonald and Jane's. ISBN 0-354-01027-1.

- Roberts, N. (1978). Armstrong Whitworth Whitley. Aircraft Crash Log. no isbn. Leeds: N. Roberts.

- Roberts, R. N. (1986). The Whitley File. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air-Britain (Historians). ISBN 0-85130-127-4.

- Swanborough, Gordon (1997). British Aircraft at War, 1939–1945. East Sussex: HPC. ISBN 0-9531421-0-8.

- Thetford, Owen. Aircraft of the Royal Aircraft, 1918–57. London: Putnam & Company Ltd., 1957.

- Turner-Hughes, Charles. "Armstrong Whitworth's Willing Whitley". Air Enthusiast, No. 9, February–May 1979, pp. 10–25. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Wixey, Ken. Armstrong Whitworth Whitley (Warpaint Series No. 21). Denbigh East, Bletchley, UK: Hall Park Books, 1999. OCLC 65202527

External links

- The Whitley Project

- Flight cutaway of Whitley

- Machine Gun Skeet Archived 6 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine August 1940 Popular Mechanics