| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Basic lead carbonate | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.901 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2 | |

| Molar mass | 775.633 g/mol |

| Appearance | White powder |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

Lead poisoning |

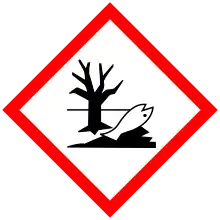

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| H302, H332, H360, H373, H410 | |

| P201, P202, P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P273, P281, P301+P312, P304+P312, P304+P340, P308+P313, P312, P314, P330, P391, P405, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

White lead is the basic lead carbonate 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2.[1] It is a complex salt, containing both carbonate and hydroxide ions. White lead occurs naturally as a mineral, in which context it is known as hydrocerussite,[1] a hydrate of cerussite.[2] It was formerly used as an ingredient for lead paint and a cosmetic called Venetian ceruse, because of its opacity and the satiny smooth mixture it made with dryable oils. However, it tended to cause lead poisoning, and its use has been banned in most countries.[3]

White lead compounds known as lead soap were also used as additive for lubricants for bearings and in machine shops.[4] Lead soap was also used as an oil drying agent for paints made with drying oil or air drying paints made with alkyd resins. Lead is often used with cobalt driers. Lead free substitutes have been developed to replace this use of lead in paint.

History

What is commonly known today as the "Dutch method" for the preparation of white lead was described as early as Theophrastus of Eresos[5] (ca. 300 BC), in his brief work on rocks or minerals, On Stones or History of Stones. His directions for the process were repeated throughout history by many authors of chemical and alchemical literature. The uses of cerussa were described as an external medication and pigment.[6]

Clifford Dyer Holley quotes from Theophrastus' History of Stones[7] as follows, in his book The Lead and Zinc Pigments.

Lead is placed in earthen vessels over sharp vinegar, and after it has acquired some thickness of a sort of rust, which it commonly does in about ten days, they open the vessels and scrape it off, as it were, in a sort of foulness; they then place the lead over vinegar again, repeating over and over again the same method of scraping it till it has wholly dissolved. What has been scraped off they then beat to powder and boil for a long time, and what at last subsides to the bottom of the vessel is ceruse.[8]

Later descriptions of the Dutch process involved casting metallic lead as thin buckles and corroded with acetic acid in the presence of carbon dioxide. This was done by placing them over pots with a little vinegar (which contains acetic acid). These were stacked up and covered with a mixture of decaying dung and spent tanner's bark, which supplied the CO2, and left for six to fourteen weeks, by which time the blue-grey lead had corroded to white lead. The pots were then taken to a separating table where scraping and pounding removed the white lead from the buckles. The powder was then dried and packed for shipment or shipped as a paste.[9] One benefit of the process was that it was not necessary to dry the paste of white lead, removing its water. All that needed was to mill the paste with linseed oil, and the white lead would take up the oil and reject the residual water, to give white lead in oil.

Paints

White lead has been the principal white pigment of classical European oil painting. There have been claims that it is partly responsible for darkening of old paintings over time, reacting with trace amounts of hydrogen sulfide in the air to produce black lead sulfide. Other authorities dispute this; the most traditional view is that impermanent pigments and dirty varnish (which is often cleanable) are more likely responsible for darkening.

White lead has been mostly supplanted in artistic use by titanium white, which has much higher tinting strength than white lead.[10] Critics argue that substitutes like zinc oxide and titanium dioxide are more reactive, become brittle, and can flake off.[11][12] White lead is less used by today's painters, not because of its toxicity directly; but simply because its toxicity in other contexts has led to trade restrictions that make white lead difficult for artists to obtain in sufficient quantities.[13] Winsor & Newton, the English paint company, was restricted in 2014 from selling its flake white in tubes and now must sell exclusively in 150 ml (5.3 imp fl oz; 5.1 US fl oz) tins.[14]

In the eighteenth century, white lead paints were routinely used to repaint the hulls and floors of Royal Navy vessels, to waterproof the timbers and limit infestation by shipworm.[15]

Other synonyms (as an art pigment)

Among the synonyms for white lead are Berlin white, Cremnitz white, Dutch white lead, flake white, Flemish white, Krems white, London white, Pigment White 1, Roman white, silver white, slate white and Vienna white.[16]

See also

References

- 1 2 Wiberg, Egon; Holleman, Arnold Frederick (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Elsevier. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ↑ see mineral hydration

- ↑ Hernberg, Sven (September 2000). "Lead Poisoning in a Historical Perspective" (PDF). American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 38 (3): 244–254. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.477.2081. doi:10.1002/1097-0274(200009)38:3<244::AID-AJIM3>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID 10940962. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-13. Retrieved 2015-04-12.

- ↑ Klemgard, E.N. (1937). "Lead base greases". Lubricating Greases Their Manufacture And Use. Reinhold Publishing Corporation. p. 677.

- ↑ J. R. Partington, A Short History of Chemistry (1937)

- ↑ Stillman, John Maxson (1924). The Story of Early Chemistry. D. Appleton. pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Theophrastus, History of Stones, p.223

- ↑ Holley, Clifford Dyer (1909). The Lead and Zinc Pigments. John Wiley & Sons. p. 2.

- ↑ Lead411.org Archived 2008-04-03 at the Wayback Machine based on Warren, Christian. "Toxic Purity: The progressive era origins of America’s lead paint poisoning epidemic". Business History Review. Winter 1999, Vol. 73(4)

- ↑ Laver, M. (1997). "Titanium Dioxide Whites". In Fitzhugh, E. W. (ed.). Artists' Pigments. Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. p. 309.

- ↑ "Zinc White: Problems in Oil Paint". The Smithsonian's Museum Conservation Institute exposes long-term problems with zinc white

- ↑ Macchia, Andrea; Cesaro, Stella; Keheyan, Yeghis; Ruffolo, Silvestro; La Russa, Mauro (2015). "White zinc in Linseed Oil Paintings: Chemical, Mechanical and Aesthetic Aspects". Periodico di Mineralogia. 84 (3A): 483–495. doi:10.2451/2015PM0027.

- ↑ Raine, Craig (5 September 2020). "Epic of gossip (review of The Lives of Lucian Freud : Fame 1968-2011 by William Feaver". The Spectator: 30/2.

- ↑ "Choosing a white in oil colour". Winsor & Newton. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

For reasons of toxicity these Lead White colours are only available in tins in the EU.

- ↑ Hough, Richard (1994). Captain James Cook. Hodder and Stoughton. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-340-82556-3.

- ↑ "Lead white". Conservation and Art Materials Encyclopedia Online (CAMEO). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Massachusetts). Retrieved 6 June 2019.

Further reading

- Gettens, R.J., Kühn, H. and Chase, W.T. "Lead White", in Roy, A., (Ed), Artists' Pigments, Vol 2, Oxford University Press, 1993, pp. 67–81

External links

- Lead white, Colourlex