Delft | |

|---|---|

City and municipality | |

A view of Delft with the Oude Kerk in the centre | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nickname: Prinsenstad (Prince City) | |

.svg.png.webp) Location in South Holland | |

Delft Location within the Netherlands  Delft Location within Europe | |

| Coordinates: 52°0′42″N 4°21′33″E / 52.01167°N 4.35917°E | |

| Country | Netherlands |

| Province | South Holland |

| City Hall | Delft City Hall |

| Government | |

| • Body | Municipal council |

| • Mayor | Marja van Bijsterveldt (CDA) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 24.06 km2 (9.29 sq mi) |

| • Land | 22.65 km2 (8.75 sq mi) |

| • Water | 1.41 km2 (0.54 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (January 2021)[4] | |

| • Total | 103,581 |

| • Density | 4,573/km2 (11,840/sq mi) |

| Demonyms |

|

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postcodes | 2600–2629 |

| Area code | 015 |

| Website | www |

Delft (Dutch pronunciation: [ˈdɛl(ə)ft] ⓘ) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. It is located between Rotterdam, to the southeast, and The Hague, to the northwest. Together with them, it is a part of both the Rotterdam–The Hague metropolitan area and the Randstad.

Delft is a popular tourist destination in the Netherlands, famous for its historical connections with the reigning House of Orange-Nassau, for its blue pottery, for being home to the painter Jan Vermeer, and for hosting Delft University of Technology (TU Delft). Historically, Delft played a highly influential role in the Dutch Golden Age.[5][6][7][8] In terms of science and technology, thanks to the pioneering contributions of Antonie van Leeuwenhoek[9][10] and Martinus Beijerinck,[11] Delft can be considered to be the birthplace of microbiology.

History

Early history

.jpg.webp)

The city of Delft came into being beside a canal, the 'Delf', which comes from the word delven, meaning to delve or dig, and this led to the name Delft. At the elevated place where this 'Delf' crossed the creek wall of the silted up river Gantel, a Count established his manor, probably around 1075. Partly because of this, Delft became an important market town, the evidence for which can be seen in the size of its central market square.

Having been a rural village in the early Middle Ages, Delft developed into a city, and on 15 April 1246, Count Willem II granted Delft its city charter. Trade and industry flourished. In 1389 the Delfshavensche Schie canal was dug through to the river Maas, where the port of Delfshaven was built, connecting Delft to the sea.

Until the 17th century, Delft was one of the major cities of the then county (and later province) of Holland. In 1400, for example, the city had 6,500 inhabitants, making it the third largest city after Dordrecht (8,000) and Haarlem (7,000). In 1560, Amsterdam, with 28,000 inhabitants, had become the largest city, followed by Delft, Leiden and Haarlem, which each had around 14,000 inhabitants.

In 1536, a large part of the city was destroyed by the great fire of Delft.

The town's association with the House of Orange started when William of Orange (Willem van Oranje), nicknamed William the Silent (Willem de Zwijger), took up residence in 1572 in the former Saint-Agatha convent (subsequently called the Prinsenhof). At the time he was the leader of growing national Dutch resistance against Spanish occupation, known as the Eighty Years' War. By then Delft was one of the leading cities of Holland and was equipped with the necessary city walls to serve as a headquarters. In October 1573, an attack by Spanish forces was repelled in the Battle of Delft.

After the Act of Abjuration was proclaimed in 1581, Delft became the de facto capital of the newly independent Netherlands, as the seat of the Prince of Orange.

When William was shot dead on 10 July 1584 by Balthazar Gerards in the hall of the Prinsenhof (now the Prinsenhof Museum), the family's traditional burial place in Breda was still in the hands of the Spanish. Therefore, he was buried in the Delft Nieuwe Kerk (New Church), starting a tradition for the House of Orange that has continued to the present day.

Around this time, Delft also occupied a prominent position in the field of printing.

A number of Italian glazed earthenware makers settled in the city and introduced a new style. The tapestry industry also flourished when famous manufacturer François Spierincx moved to the city. In the 17th century, Delft experienced a new heyday, thanks to the presence of an office of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) (opened in 1602) and the manufacture of Delft Blue china.

A number of notable artists based themselves in the city, including Leonard Bramer, Carel Fabritius, Pieter de Hoogh, Gerard Houckgeest, Emanuel de Witte, Jan Steen, and Johannes Vermeer. Reinier de Graaf and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek received international attention for their scientific research.

Explosion

The Delft Explosion, also known in history as the Delft Thunderclap, occurred on 12 October 1654[12] when a gunpowder store exploded, destroying much of the city. Over a hundred people were killed and thousands were injured.[13]

About 30 t (29.5 long tons; 33.1 short tons) of gunpowder were stored in barrels in a magazine in a former Clarist convent in the Doelenkwartier district, where the Paardenmarkt is now located. Cornelis Soetens, the keeper of the magazine, opened the store to check a sample of the powder and a huge explosion followed. Luckily, many citizens were away, visiting a market in Schiedam or a fair in The Hague.

Today, the explosion is primarily remembered for killing Rembrandt's most promising pupil, Carel Fabritius, and destroying almost all of his works.

Delft artist Egbert van der Poel painted several pictures of Delft showing the devastation.

The gunpowder store (Dutch: Kruithuis) was subsequently re-housed, a 'cannonball's distance away', outside the city, in a new building designed by architect Pieter Post.[14]

Sights

The city centre retains a large number of monumental buildings, while in many streets there are canals of which the banks are connected by typical bridges, altogether making this city a notable tourist destination.[15]

Historical buildings and other sights of interest include:

- Oude Kerk (Old Church), constructed between 1246 and 1350. Buried here: Piet Hein, Johannes Vermeer, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek.

- Nieuwe Kerk (New Church), constructed between 1381 and 1496. It contains the Dutch royal family's burial vault which, between funerals, is sealed with a 5,000 kg (11,020 lb) cover stone.

- A statue of Hugo Grotius created by Franciscus Leonardus Stracké in 1886, located on the Markt near the Nieuwe Kerk.

- The Prinsenhof (Princes' Court), now a museum.[15]

- City Hall on the Markt.

- The Oostpoort (Eastern gate), built around 1400. This is the only remaining gate of the old city walls.

- The Gemeenlandshuis Delfland, or Huyterhuis, built in 1505, which has housed the Delfland regional water authority since 1645.

- The Vermeer Centre in the re-built Guild house of St. Luke.

- The historical "Waag" building (Weigh house).

- Windmill De Roos, a tower mill built c. 1760. Restored to working order in 2013.[16] Another windmill that formerly stood in Delft, Het Fortuyn, was dismantled in 1917 and re-erected at the Netherlands Open Air Museum, Arnhem, Gelderland in 1920.

- Royal Delft also known as De Porceleyne Fles, is a great place which showcases Delft ware.[17][18]

- Science Center attracts kids as well as adults.[19][20]

Delft City Hall

Delft City Hall Eastern Gate (Oostpoort)

Eastern Gate (Oostpoort) The Old Church tower

The Old Church tower Oude Langendijk

Oude Langendijk

Culture

Delft is well known for the Delft pottery ceramic products[15] which were styled on the imported Chinese porcelain of the 17th century. The city had an early start in this area since it was a home port of the Dutch East India Company. It can still be seen at the pottery factories De Koninklijke Porceleyne Fles (or Royal Delft) and De Delftse Pauw, while new ceramics and ceramic art can be found at the Gallery Terra Delft.[21]

The painter Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) was born in Delft. Vermeer used Delft streets and home interiors as the subject or background in his paintings.[15] Several other famous painters lived and worked in Delft at that time, such as Pieter de Hoogh, Carel Fabritius, Nicolaes Maes, Gerard Houckgeest and Hendrick Cornelisz. van Vliet. They were all members of the Delft School. The Delft School is known for its images of domestic life and views of households, church interiors, courtyards, squares and the streets of Delft. The painters also produced pictures showing historic events, flowers, portraits for patrons and the court as well as decorative pieces of art.

Delft supports creative arts' companies. From 2001 the Bacinol, a building that had been disused since 1951, began to house small companies in the creative arts sector.[22] Its demolition started in December 2009, making way for the new railway tunnel in Delft. The occupants of the building, as well as the name 'Bacinol', moved to another building in the city. The name Bacinol relates to Dutch penicillin research during WWII.

Education

Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) is one of four universities of technology in the Netherlands.[23] It was founded as an academy for civil engineering in 1842 by King William II. Today, well over 21,000 students are enrolled.[24]

The UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education, providing postgraduate education for people from developing countries, draws on the strong tradition in water management and hydraulic engineering of the Delft university.

The Hague University of Applied Sciences has a building on the Delft University of Technology campus. It opened in 2009[25] and offers several bachelor degrees for the Faculty of Technology, Innovation & Society.

Inholland University of Applied Sciences also has a building on the Delft University of Technology campus. Several bachelor degrees for the Agri, Food & Life Sciences faculty and the Engineering, Design and Computing faculty are being taught at the Delft campus.

Economy

In the local economic field, essential elements are:

- education; (amongst others Delft University of Technology) (As of 2017 21.651 students and 4.939 full-time employees),

- scientific research; (amongst others "TNO" Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research), Stichting Deltares, Nederlands Normalisatie-Instituut, UNESCO-IHE Institute for water education, Technopolis Innovation Park;

- tourism; (about one million registered visitors a year),

- industry; (DSM Gist Services BV, (Delftware) earthenware production by De Koninklijke Porceleyne Fles, Exact Software Nederland BV, TOPdesk, Ampelmann)

- retail; (IKEA (Inter IKEA Systems B.V., owner and worldwide franchisor of the IKEA Concept, is based in Delft), Makro, Eneco Energy NV).

Nature and recreation

East of Delft lies a relatively large nature and recreation area called the "Delftse Hout" ("Delft Wood").[26] Through the forest lie bike, horse-riding and footpaths. It also includes a vast lake (suitable for swimming and windsurfing), narrow beaches, a restaurant, and community gardens, plus camping ground and other recreational and sports facilities. (There is also a facility for renting bikes from the station.)

Inside the city, apart from a central park, there are several smaller town parks, including "Nieuwe Plantage", "Agnetapark", "Kalverbos". There is also the Botanical Garden of the TU and an arboretum in Delftse Hout.

Notable people

._Natuurkundige_te_Delft_Rijksmuseum_SK-A-957.jpeg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Delft is the birthplace of:

Dutch Golden Age

- Jacob Willemsz Delff the Elder, (ca. 1550–1601), portrait painter

- Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt (1567–1641), painter

- Willem van der Vliet (c. 1584–1642), painter

- Adriaen van de Venne (1589–1662), painter

- Adriaen Cornelisz van Linschoten (1590–1677), painter

- Daniël Mijtens (ca. 1590–1647/48), portrait painter

- Leonaert Bramer (1596–1674), painter of genre, religious, and history paintings

- Pieter Jansz van Asch (1603–ca. 1678), painter

- Evert van Aelst (1602–1657), still life painter

- Hendrick Cornelisz. van Vliet (ca. 1611–1675), painter of church interiors

- Harmen Steenwijck (ca. 1612–ca. 1656), painter of still lifes and fruit

- Jacob Willemsz Delff the Younger (1619–1661), portrait painter

- David Beck (1621–1656), portrait painter

- Egbert van der Poel (1621–1664), genre and landscape painter

- Daniel Vosmaer (1622–1666), painter

- Willem van Aelst (1627–1683), artist of still-lifes

- Hendrick van der Burgh (1627–after 1664), genre painter

- Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), painter of domestic interior scenes

- Ary de Milde (1634–1708), ceramist

Public thinking and service

- Christian van Adrichem (1533—1585), Catholic priest and theological writer[27]

- Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn (1556–1623), one of the first Dutchmen in Japan

- Hugo Grotius (1583–1645), humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian and jurist who laid the foundations for international law

- Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange (1584–1647), sovereign prince of Orange and stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders & Overijssel from 1625 to 1647

- Philippus Baldaeus (1632–1671), minister in Jaffna

- Diederik Durven (1676–1740), Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies from 1729 to 1732

- Abraham van der Weijden (1743–1773), ship's captain, initiated of Freemasonry in South Africa

- Gerrit Paape (1752–1803), painter of earthenware and stoneware, poet, journalist, novelist, judge, columnist and finally a ministerial civil servant

- Aegidius van Braam (1758–1822), naval vice-admiral

- Agneta Matthes (1847–1909), entrepreneur, manufactured yeast using the cooperative movement and housed workers at Agnetapark

- Henk Zeevalking (1922–2005), politician and jurist

- Piet Bukman (born 1934), politician and diplomat

- Klaas de Vries (born 1943), politician and jurist

- Atzo Nicolaï (born 1960), politician

- Marja van Bijsterveldt (born 1961), politician, Mayor of Delft since 2016

- Alexander Pechtold (born 1965), politician and art historian

Science and business

- Adolphus Vorstius (1597–1663), physician and botanist

- Martin van den Hove (1605–1639), astronomer and mathematician

- Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723), father of microbiology and developer of the microscope

- Nicolaas Kruik (1678–1754), land surveyor, cartographer, astronomer, weatherman and eponym of the Museum De Cruquius

- Martin van Marum (1750–1837), physician, inventor, scientist and teacher[28]

- Jacob Gijsbertus Samuël van Breda (1788–1867), biologist and geologist

- Philippe-Charles Schmerling (1791–1836), prehistorian, geologist and pioneer in paleontology

- Martinus Beijerinck (1851–1931), microbiologist, discovered viruses, lived and worked in Delft

- Guillaume Daniel Delprat CBE (1856–1937), metallurgist, mining engineer and businessman

- Frederik H. Kreuger (1928–2015), high-voltage scientist, academic and inventor

- Marjo van der Knaap (born 1958), professor of pediatric neurology, white matter researcher

- Antoni Folkers (born 1960), architect, humanist

- Peter Schrijver (born 1963), historical linguist

- Ionica Smeets (born 1979), mathematician, science journalist, TV presenter and academic

- Boyan Slat (born 1994), inventor and entrepreneur, CEO of The Ocean Cleanup

Art

- Suzanne Manet (1829–1906), pianist, wife and model of painter Édouard Manet

- Betsy Perk (1833–1906), author of novels and plays, pioneer of the Dutch women's movement

- Ton Lutz (1919–2009) and Pieter Lutz (1927–2009), brothers and actors[29]

- Bram Bogart (1921–2012), expressionist painter of the COBRA group

- Cor Dam (born 1935), sculptor, painter, illustrator and ceramist

- Kader Abdolah (born 1954), poet and columnist

- Michèle Van de Roer (born 1956), artist, designer, photographer and engraver

- Mariska Hulscher (born 1964), TV presenter[30]

- Emma Kirchner (1830 - 1909), first woman photographer in Delft area[31]

- Wessel van Diepen (born 1966), radio host, music producer and former TV presenter[32]

- Rob Das (born 1969), film and TV actor, director and writer[33]

- Jan-Willem van Ewijk (born 1970), film director, actor and screenwriter[34]

- Ricky Koole (born 1972) a Dutch singer and film actress[35]

- Vincent de Moor (born 1973), trance musician and remixer

- Roel van Velzen (born 1978), singer

- Marly van der Velden (born 1988), actress and fashion designer[36]

- Rose Schmits (born c. 1988), potter and trans activist

Sport

- Jan Thomée (1886–1954), footballer, team bronze medallist at the 1908 Summer Olympics

- Henri van Schaik (1899–1991), horse rider, team silver medallist in the 1936 Summer Olympics

- Tinus Osendarp (1916–2002), sprint runner, twice bronze medallist at the 1936 Summer Olympics

- Stien Kaiser (born 1938), speed skater, twice bronze medallist at the 1968 Winter Olympics and gold and silver medallist in the 1972 Winter Olympics

- Pieter van der Kruk (born 1941), heavyweight weightlifter and shot putter, competed at the 1968 Summer Olympics

- Jan Timman (born 1951), chess grandmaster, raised in Delft

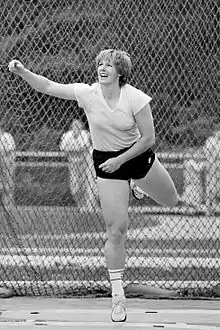

- Ria Stalman (born 1951), discus thrower and shot putter, gold medallist in the discus at the 1984 Summer Olympics

- Frank Leistra (born 1960), field hockey goalkeeper, team bronze medallist at the 1988 Summer Olympics

- Ken Monkou (born 1964), football player with 356 club caps

- Eeke van Nes (born 1969), rower, team bronze medallist at the 1996 Summer Olympics and team silver medallist at the 2000 Summer Olympics

- Thamar Henneken (born 1979), freestyle swimmer, team silver medallist at the 2000 Summer Olympics

- Ard van Peppen (born 1985), footballer with over 350 club caps

- Sytske de Groot (born 1986), rower, team bronze medallist at the 2012 Summer Olympics

- Aaron Meijers (born 1987), footballer with almost 400 club caps

- Michaëlla Krajicek (born 1989), tennis player

- Arantxa Rus (born 1990), tennis player

- Kelly Vollebregt (born 1995), handball player

- Victoria Pelova (born 1999), football player

- Tijmen van der Helm (born 2004), racing driver

Miscellaneous

- Nuna is a series of crewed solar-powered vehicles, built by students at the Delft University of Technology, that won the World solar challenge in Australia seven times in the last nine competitions (in 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, 2013, 2015 and 2017).[37]

- The so-called "Superbus" project aims to develop high-speed coaches capable of speeds of up to 250 km/h (155 mph) together with the supporting infrastructure including special highway lanes constructed separately next to the nation's highways; this project was led by Dutch astronaut professor Wubbo Ockels of the Delft University of Technology.

- Members of both Delft Student Rowing Clubs Proteus-Eretes and Laga have won many international trophies, including Olympic medals, in the past.

- Formula Student Team Delft is a student racing team that has won the Formula Student competition format in Germany three times in a row, their workplace is located along the shie.[38]

- The Human Power Team Delft & Amsterdam, a team consisting mainly of students from the Delft University of Technology, has won The World Human Powered Speed Challenge (WHPSC) four times. This is an international contest for recumbents in the US state of Nevada, the aim of which is to break speed records.[39] They set the world record of 133.78 kilometres an hour (83.13 mph) in 2013.

International relations

Twin towns

|

|

|

Transport

- Delft railway station; (As of February 2015, located in a new building.)[42]

- Delft Campus railway station

Trains stopping at these stations connect Delft with, among others, the nearby cities of Rotterdam and The Hague, as often as every five minutes, for most of the day.

There are several bus routes from Delft to similar destinations. Trams frequently travel between Delft and The Hague via special double tracks crossing the city.

The whole city center and adjacent areas are a paid on-street parking area. In 2018, with the day parking fee of 29.5 Euro, it was the most expensive on-street parking area in the Netherlands, with the city centers of Deventer and Dordrecht being second and third, respectively.[43]

See also

Gallery

Delft city view |

"Gemeenlandshuis" |

Nieuwe Kerk (New Church) |

Legermuseum (Army museum) |

Central Market Square |

City sight ("Vrouw Juttenland") |

Huybrechtstower |

"Koornbeurs" |

Observatory |

Former station building |

New station building |

Main canal "Delftse Schie" at sundown |

Sculpture near the church |

Streetview (het Oosteinde) |

Streetview (Dertienhuizen) |

Notes

- ↑ "Maak kennis met" [Meet.]. Burgermeester Verkerk (in Dutch). Gemeente Delft. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "Kerncijfers wijken en buurten 2020" [Key figures for neighbourhoods 2020]. StatLine (in Dutch). CBS. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ↑ "Postcodetool for 2611GX". Actueel Hoogtebestand Nederland (in Dutch). Het Waterschapshuis. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ↑ "Bevolkingsontwikkeling; regio per maand" [Population growth; regions per month]. CBS Statline (in Dutch). CBS. 1 January 2021. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ↑ Huerta, Robert D.: Giants of Delft: Johannes Vermeer and the Natural Philosophers: The Parallel Search for Knowledge during the Age of Discovery. (Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press, 2003)

- ↑ Brook, Timothy: Vermeer's Hat: The Seventeenth Century and the Dawn of the Global World. (Bloomsbury Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1596915992)

- ↑ Liedtke, Walter; Plomp, Michiel C.; Ruger, Axel; Baarsen, Reinier J.: Vermeer and the Delft School. (NYC: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013, ISBN 978-0300200294)

- ↑ Snyder, Laura J.: Eye of the Beholder: Johannes Vermeer, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, and the Reinvention of Seeing. (W. W. Norton & Company, 2015, ISBN 978-0393352887)

- ↑ Ruestow, Edward G.: The Microscope in the Dutch Republic: The Shaping of Discovery. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996)

- ↑ Fournier, Marian: The Fabric of Life: The Rise and Decline of Seventeenth-Century Microscopy. (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0801851384)

- ↑ Artenstein, Andrew W.: The discovery of viruses: advancing science and medicine by challenging dogma. (International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 16, Issue 7, July 2012, pages: e470-e473). doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2012.03.005. Andrew W. Artenstein: "By 1895 Beijerinck had returned to academia after leaving the Agricultural School for a 10-year stint in industrial microbiology in Delft, the South Holland birthplace of van Leeuwenhoek, one of the founding fathers of microbiology. During his first years at the Technical University of Delft, Beijerinck resumed the research on tobacco mosaic disease that he had started while working with Mayer. Even then, he had appreciated that the affliction was microbial in nature, although he felt that the actual agents had yet to be discovered. Beijerinck's investigations at Delft proved fruitful; he not only confirmed the infectivity of the contagium vivum fluidum—soluble living germ—despite filtration, but he importantly demonstrated that unlike bacteria, the culprit of tobacco disease of plants was incapable of independent growth, requiring the presence of living, dividing host cells in order to replicate."

- ↑ "The Day the World Came to an End: the Great Delft Thunderclap of 1654". Radio Netherlands. 14 October 2004.

- ↑ Cumming, Laura (2023). Thunderclap: A Memoir of Art and Life and Sudden Death. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-1-9821-8174-1.

- ↑ "Historie: Het Kruithuis" (in Dutch). Scoutcentrum Delft.

- 1 2 3 4 Martin Dunford (2010). The Rough Guide to The Netherlands. Penguin. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-84836-882-8. Retrieved 24 November 2011.

- ↑ "Delft, Zuid-Holland" (in Dutch). Molendatabase. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ↑ "Royal Delft. Ontdek de wereld van koninklijk Delfts Blauw". www.royaldelft.com. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ↑ "Welcome to delfthuis.com". delfthuis.com.

- ↑ "Science Centre Delft". TU Delft (in Dutch). Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ↑ "Museumkids". Museumkids.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ↑ Kitty Kilian, "10 jaar galerie Terra; Keramisch gezicht op Delft." NRC Handelsblad, 23 May 1996.

- ↑ "Art on the streets of Delft". Kunstwandeling Delft. Retrieved 2023-02-05.

- ↑ "4TU.Federation". 4tu.nl.

- ↑ "Studentenpopulatie". TU Delft. Archived from the original on 2021-04-22. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ↑ "Vestiging Delft - De Haagse Hogeschool". www.dehaagsehogeschool.nl. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- ↑ "Category:Delftse Hout". Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 01. 1907.

- ↑ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ↑ "Ton Lutz". IMDb. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ "Mariska Hulscher". IMDb. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ "Depth of Field | Scherptediepte". depthoffield.universiteitleiden.nl. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- ↑ "Wessel van Diepen". IMDb. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ "Rob Das". IMDb.

- ↑ "Jan-Willem van Ewijk". IMDb. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ "Ricky Koole". IMDb. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ "Marly van der Velden". IMDb. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ "World Solar Challenge 2017". worldsolarchallenge.org. Archived from the original on 2017-10-16. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- ↑ "HOME". DUT23.

- ↑ "The Recumbent Bicycle and Human Powered Vehicle Information Center". recumbents.com.

- ↑ (source: Delft municipality guide 2005)

- ↑ "List of Twin Towns in the Ruhr District" (PDF). © 2009 www.twins2010.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-11-28. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑ "Category:Spoorzone-project". Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ↑ "Parkeer Puzzel". Kampioen (in Dutch). Royal Dutch Touring Club (4): 18–21. April 2018.

References

- Lourens, Piet; Lucassen, Jan (1997). Inwonertallen van Nederlandse steden ca. 1300–1800. Amsterdam: NEHA. ISBN 9057420082.

Further reading

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 07 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Vermeer: A View of Delft, Anthony Bailey, Henry Holt & Company, 2001, ISBN 0-8050-6718-3