Transduction is the process by which foreign DNA is introduced into a cell by a virus or viral vector.[1] An example is the viral transfer of DNA from one bacterium to another and hence an example of horizontal gene transfer.[2] Transduction does not require physical contact between the cell donating the DNA and the cell receiving the DNA (which occurs in conjugation), and it is DNase resistant (transformation is susceptible to DNase). Transduction is a common tool used by molecular biologists to stably introduce a foreign gene into a host cell's genome (both bacterial and mammalian cells).

Discovery (bacterial transduction)

Transduction was discovered in Salmonella by Norton Zinder and Joshua Lederberg at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1952.[3]

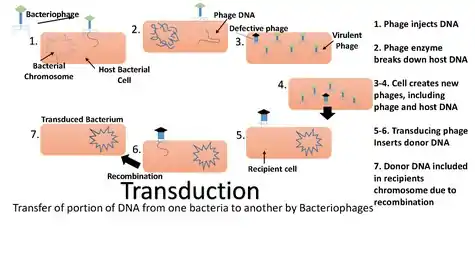

In the lytic and lysogenic cycles

Transduction happens through either the lytic cycle or the lysogenic cycle. When bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) that are lytic infect bacterial cells, they harness the replicational, transcriptional, and translation machinery of the host bacterial cell to make new viral particles (virions). The new phage particles are then released by lysis of the host. In the lysogenic cycle, the phage chromosome is integrated as a prophage into the bacterial chromosome, where it can stay dormant for extended periods of time. If the prophage is induced (by UV light for example), the phage genome is excised from the bacterial chromosome and initiates the lytic cycle, which culminates in lysis of the cell and the release of phage particles. Generalized transduction (see below) occurs in both cycles during the lytic stage, while specialized transduction (see below) occurs when a prophage is excised in the lysogenic cycle.

As a method for transferring genetic material

Transduction by bacteriophages

The packaging of bacteriophage DNA into phage capsids has low fidelity. Small pieces of bacterial DNA may be packaged into the bacteriophage particles. There are two ways that this can lead to transduction.

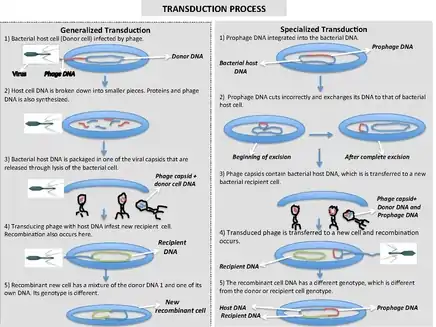

Generalized transduction

Generalized transduction occurs when random pieces of bacterial DNA are packaged into a phage. It happens when a phage is in the lytic stage, at the moment that the viral DNA is packaged into phage heads. If the virus replicates using 'headful packaging', it attempts to fill the head with genetic material. If the viral genome results in spare capacity, viral packaging mechanisms may incorporate bacterial genetic material into the new virion. Alternatively, generalized transduction may occur via recombination. Generalized transduction is a rare event and occurs on the order of 1 phage in 11,000.

The new virus capsule that contains part bacterial DNA then infects another bacterial cell. When the bacterial DNA packaged into the virus is inserted into the recipient cell three things can happen to it:

- The DNA is recycled for spare parts.

- If the DNA was originally a plasmid, it will re-circularize inside the new cell and become a plasmid again.

- If the new DNA matches with a homologous region of the recipient cell's chromosome, it will exchange DNA material similar to the actions in bacterial recombination.

Specialized transduction

Specialized transduction is the process by which a restricted set of bacterial genes is transferred to another bacterium. Those genes that are located adjacent to the prophage are transferred due to improper excision. Specialized transduction occurs when a prophage excises imprecisely from the chromosome so that bacterial genes lying adjacent to it are included in the excised DNA. The excised DNA along with the viral DNA is then packaged into a new virus particle, which is then delivered to a new bacterium when the phage attacks new bacterium. Here, the donor genes can be inserted into the recipient chromosome or remain in the cytoplasm, depending on the nature of the bacteriophage.

When the partially encapsulated phage material infects another cell and becomes a prophage, the partially coded prophage DNA is called a "heterogenote".

An example of specialized transduction is λ phage in Escherichia coli.[4]

Lateral transduction

Lateral transduction is the process by which very long fragments of bacterial DNA are transferred to another bacterium. So far, this form of transduction has been only described in Staphylococcus aureus, but it can transfer more genes and at higher frequencies than generalized and specialized transduction. In lateral transduction, the prophage starts its replication in situ before excision in a process that leads to replication of the adjacent bacterial DNA. After which, packaging of the replicated phage from its pac site (located around the middle of the phage genome) and adjacent bacterial genes occurs in situ, to 105% of a phage genome size. Successive packaging after initiation from the original pac site leads to several kilobases of bacterial genes being packaged into new viral particles that are transferred to new bacterial strains. If the transferred genetic material in these transducing particles provides sufficient DNA for homologous recombination, the genetic material will be inserted into the recipient chromosome. Because multiple copies of the phage genome are produced during in situ replication, some of these replicated prophages excise normally (instead of being packaged in situ), producing normal infectious phages.[5]

Mammalian cell transduction with viral vectors

Transduction with viral vectors can be used to insert or modify genes in mammalian cells. It is often used as a tool in basic research and is actively researched as a potential means for gene therapy.

Process

In these cases, a plasmid is constructed in which the genes to be transferred are flanked by viral sequences that are used by viral proteins to recognize and package the viral genome into viral particles. This plasmid is inserted (usually by transfection) into a producer cell together with other plasmids (DNA constructs) that carry the viral genes required for the formation of infectious virions. In these producer cells, the viral proteins expressed by these packaging constructs bind the sequences on the DNA/RNA (depending on the type of viral vector) to be transferred and insert it into viral particles. For safety, none of the plasmids used contains all the sequences required for virus formation, so that simultaneous transfection of multiple plasmids is required to get infectious virions. Moreover, only the plasmid carrying the sequences to be transferred contains signals that allow the genetic materials to be packaged in virions so that none of the genes encoding viral proteins are packaged. Viruses collected from these cells are then applied to the cells to be altered. The initial stages of these infections mimic infection with natural viruses and lead to expression of the genes transferred and (in the case of lentivirus/retrovirus vectors) insertion of the DNA to be transferred into the cellular genome. However, since the transferred genetic material does not encode any of the viral genes, these infections do not generate new viruses (the viruses are "replication-deficient").

Some enhancers have been used to improve transduction efficiency such as polybrene, protamine sulfate, retronectin, and DEAE Dextran.[6]

Medical applications

- Gene therapy: Correcting genetic diseases by direct modification of genetic error.

See also

- Electroporation – use of an electrical field to increase cell membrane permeability.

- Phage therapy – therapeutic use of bacteriophages.

- Signal transduction

- Transfection – means of inserting DNA into a cell.

- Transformation (genetics) – means of inserting DNA into a cell.

- Viral vector – commonly used tool to deliver genetic material into cells.

References

- ↑ Transduction, Genetic at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ↑ Jones E, Hartl DL (1998). Genetics: principles and analysis. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7637-0489-6.

- ↑ Zinder ND, Lederberg J (November 1952). "Genetic exchange in Salmonella". Journal of Bacteriology. 64 (5): 679–99. doi:10.1128/JB.64.5.679-699.1952. PMC 169409. PMID 12999698.

- ↑ Snyder L, Peters JE, Henkin TM, Champness W (2013). "Lysogeny: the λ Paradigm and the Role of Lysogenic Conversion in Bacterial Pathogenesis". Molecular Genetics of Bacteria (4th ed.). Washington, DC: ASM Press. pp. 340–343. ISBN 9781555816278.

- ↑ Chen J.; et al. (13 October 2018). "Genome hypermobility by lateral transduction". Science. 362 (6411): 207–212. Bibcode:2018Sci...362..207C. doi:10.1126/science.aat5867. hdl:20.500.11820/a13340e9-873c-48c5-87c6-e2e92d1fffa1. PMID 30309949.

- ↑ Denning W, Das S, Guo S, Xu J, Kappes JC, Hel Z (March 2013). "Optimization of the transductional efficiency of lentiviral vectors: effect of sera and polycations". Molecular Biotechnology. 53 (3): 308–14. doi:10.1007/s12033-012-9528-5. PMC 3456965. PMID 22407723.

External links

- Genetic+Transduction at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview at ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- http://www.med.umich.edu/vcore/protocols/RetroviralCellScreenInfection13FEB2006.pdf (transduction protocol)

- Generalized and Specialized transduction at sdsu.edu