Victoria | |

|---|---|

| The Corporation of the City of Victoria[1] | |

From the top, left to right: the British Columbia Parliament Buildings; Downtown Victoria; Craigdarroch Castle; Christ Church Cathedral; the Empress Hotel; and the Float Home Village at Fisherman's Wharf | |

|

Logo | |

| Nickname: | |

| Motto(s): Semper Liber (Latin) "Forever free" | |

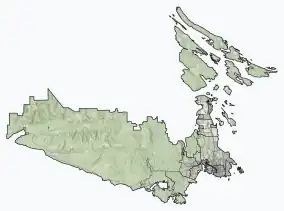

Victoria Location of Victoria within the Capital Regional District | |

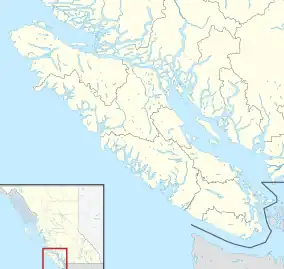

Victoria Location within British Columbia  Victoria Location within Canada  Victoria Location within North America  Victoria Victoria (North America) | |

| Coordinates: 48°25′42″N 123°21′53″W / 48.42833°N 123.36472°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | British Columbia |

| Regional district | Capital Regional District |

| Historic colonies | C. of Vancouver Island (1848–66) C. of British Columbia (1866–71) |

| Incorporated | 2 August 1862[4] |

| Named for | Queen Victoria |

| Seat | Victoria City Hall |

| Government | |

| • Type | Elected city council |

| • Body | Victoria City Council |

| • Mayor | Marianne Alto |

| • MP | Laurel Collins (NDP) |

| • MLAs | Grace Lore (BC NDP), Rob Fleming (BC NDP) |

| Area | |

| • City | 19.47 km2 (7.52 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 215.88 km2 (83.35 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 696.15 km2 (268.79 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 23 m (75 ft) |

| Population | |

| • City | 91,867 |

| • Rank | 66th in Canada |

| • Density | 4,722.3/km2 (12,231/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 7th in Canada |

| • Urban | 397,237 |

| • Urban density | 1,555.0/km2 (4,027/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 397,237 (16th in Canada) |

| • Metro density | 571.3/km2 (1,480/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Victorian |

| Time zone | UTC–08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (PDT) |

| Forward sortation area | |

| Area codes | 250, 778, 236, 672 |

| NTS Map | 92B6 Victoria |

| GNBC Code | JBOBQ[8] |

| GDP (Victoria CMA) | CA$22.5 billion (2020)[9] |

| GDP per capita (Victoria CMA) | $53,446 (2016) |

| Website | www |

Victoria is the capital city of the Canadian province of British Columbia, on the southern tip of Vancouver Island off Canada's Pacific coast. The city has a population of 91,867, and the Greater Victoria area has a population of 397,237. The city of Victoria is the seventh most densely populated city in Canada with 4,406 inhabitants per square kilometre (11,410/sq mi).[10]

Victoria is the southernmost major city in Western Canada and is about 100 km (62 mi) southwest from British Columbia's largest city of Vancouver on the mainland. The city is about 100 km (62 mi) from Seattle by airplane, seaplane, ferry, or the Victoria Clipper passenger-only ferry, and 40 km (25 mi) from Port Angeles, Washington, by ferry Coho across the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Named for Queen Victoria, the city is one of the oldest in the Pacific Northwest, with British settlement beginning in 1843. The city has retained a large number of its historic buildings, in particular its two most famous landmarks, the Parliament Buildings (finished in 1897 and home of the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia) and the Empress Hotel (opened in 1908). The city's Chinatown is the second oldest in North America, after that of San Francisco. The region's Coast Salish First Nations peoples established communities in the area long before European settlement, which had large populations at the time of European exploration.

Known as "the Garden City", Victoria is an attractive city and a popular tourism destination and has a regional technology sector that has risen to be its largest revenue-generating private industry.[11] Victoria is in the top 20 world cities for quality of life,[12] according to Numbeo.

History

Prior to the arrival of European navigators in the late 1700s, the Greater Victoria area was home to several communities of Coast Salish peoples, including the Lək̓ʷəŋən (Lekwungen) and W̱SÁNEĆ (Saanich) peoples.

Early European exploration (1770–1871)

The Spanish and British took up the exploration of the northwest coast, beginning with the visits of Juan Pérez in 1774, and of James Cook in 1778. Although the Victoria area of the Strait of Juan de Fuca was not explored until 1790, Spanish sailors visited Esquimalt Harbour (just west of Victoria proper) in 1790, 1791, and 1792.

In 1841 James Douglas was charged with the duty of setting up a trading post on the southern tip of Vancouver Island. Upon the recommendation by George Simpson a new more northerly post should be built in case Fort Vancouver fell into American hands (see Oregon boundary dispute). Douglas founded Fort Victoria on the site of present-day Victoria in anticipation of the outcome of the Oregon Treaty in 1846, extending the British North America/United States border along the 49th parallel from the Rockies to the Strait of Georgia.[13]

_VICTORIA_FROM_JAMES'_BAY_LOOKING_UP_GOVERNMENT_STREET.jpg.webp)

Erected in 1843 as a Hudson's Bay Company trading post on a site originally called Camosack meaning "rush of water".[14] Known briefly as "Fort Albert", the settlement was renamed Fort Victoria in November 1843, in honour of Queen Victoria.[15][16] The Songhees established a village across the harbour from the fort. The Songhees' village was later moved north of Esquimalt in 1911.The crown colony was established in 1849. Between the years 1850–1854 a series of treaty agreements known as the Douglas Treaties were made with indigenous communities to purchase certain plots of land in exchange for goods.[17] These agreements contributed to a town being laid out on the site and made the capital of the colony, though controversy has followed about the ethical negotiation and upholding of rights by the colonial government.[18] The superintendent of the fort, Chief Factor James Douglas was made the second governor of the Vancouver Island Colony (Richard Blanshard was first governor, Arthur Edward Kennedy was third and last governor), and would be the leading figure in the early development of the city until his retirement in 1864.

When news of the discovery of gold on the British Columbia mainland reached San Francisco in 1858, Victoria became the port, supply base, and outfitting centre for miners on their way to the Fraser Canyon gold fields, mushrooming from a population of 300 to over 5000 within a few days. Victoria was incorporated as a city in 1862.[19] In 1862 Victoria was the epicentre of the 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic which devastated First Nations, killing about two-thirds of all natives in British Columbia. In 1865, the North Pacific home of the Royal Navy was established in Esquimalt and today is Canada's Pacific coast naval base. In 1866 when the island was politically united with the mainland, Victoria was designated the capital of the new united colony instead of New Westminster – an unpopular move on the Mainland – and became the provincial capital when British Columbia joined the Canadian Confederation in 1871.

Modern history (1871–present)

%252C_1889_(38868364955).jpg.webp)

In the latter half of the 19th century, the Port of Victoria became one of North America's largest importers of opium, serving the opium trade from Hong Kong and distribution into North America. Opium trade was legal and unregulated until 1865, when the legislature issued licences and levied duties on its import and sale. The opium trade was banned in 1908.[20]

In 1886, with the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway terminus on Burrard Inlet, Victoria's position as the commercial centre of British Columbia was irrevocably lost to the city of Vancouver. The city subsequently began cultivating an image of genteel civility within its natural setting, aided by the impressions of visitors such as Rudyard Kipling, the opening of the popular Butchart Gardens in 1904 and the construction of the Empress Hotel by the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1908. Robert Dunsmuir, a leading industrialist whose interests included coal mines and a railway on Vancouver Island, constructed Craigdarroch Castle in the Rockland area, near the official residence of the province's Lieutenant Governor. His son James Dunsmuir became Premier and subsequently Lieutenant Governor of the province and built his own grand residence at Hatley Park (used for several decades as Royal Roads Military College, now civilian Royal Roads University) in the present City of Colwood.

A real-estate and development boom ended just before World War I, leaving Victoria with a large stock of Edwardian public, commercial and residential buildings that have greatly contributed to the city's character. With the economic crash and an abundance of unmarried men, Victoria became an excellent location for military recruiting. Two militia infantry battalions, the 88th Victoria Fusiliers and the 50th Gordon Highlanders, formed in the immediate pre-war period. Victoria was the home of Sir Arthur Currie. He had been a high-school teacher and real-estate agent prior to the war and was the Commanding Officer of the Gordon Highlanders in the summer of 1914. Before the end of the war he commanded the Canadian Corps.[21] A number of municipalities surrounding Victoria were incorporated during this period, including the Township of Esquimalt, the District of Oak Bay, and several municipalities on the Saanich Peninsula.[22]

Since World War II the Victoria area has seen relatively steady growth, becoming home to two major universities. Since the 1980s the western suburbs have been incorporated as new municipalities, such as Colwood and Langford, which are known collectively as the Western Communities.

Greater Victoria periodically experiences calls for the amalgamation of the thirteen municipal governments within the Capital Regional District.[23] The opponents of amalgamation state that separate governance affords residents a greater deal of local autonomy.[24] The proponents of amalgamation argue it would reduce duplication of services,[25] while allowing for more efficient use of resources and the ability to better handle broad, regional issues and long-term planning.[26]

Geography

Topography

The landscape of Victoria was formed by volcanism followed by water in various forms. Pleistocene glaciation put the area under a thick ice cover, the weight of which depressed the land below present sea level. These glaciers also deposited stony sandy loam till. As they retreated, their melt water left thick deposits of sand and gravel. Marine clay settled on what would later become dry land. Post-glacial rebound exposed the present-day terrain to air, raising beach and mud deposits well above sea level. The resulting soils are highly variable in texture, and abrupt textural changes are common. In general, clays are most likely to be encountered in the northern part of town and in depressions. The southern part has coarse-textured subsoils and loamy topsoils. Sandy loams and loamy sands are common in the eastern part adjoining Oak Bay. Victoria's soils are relatively unleached and less acidic than soils elsewhere on the British Columbia Coast. Their thick dark topsoils denote a high level of fertility which made them valuable for farming prior to urbanization.

Climate

.jpg.webp)

Depending on the classification used, Victoria either has a warm-summer Mediterranean or oceanic climate (Köppen: Csb, Trewartha: Do);[27][28] with fresh, dry, sunny summers, and cool, cloudy, rainy winters.[29]

Victoria is farther north than many "cold-winter" cities, such as Ottawa, Quebec City, and Minneapolis. However, westerly winds and Pacific Ocean currents keep Victoria's winter temperatures substantially higher, with an average January temperature of 5.0 °C (41.0 °F) compared to Ottawa, the nation's capital, with −10.2 °C (13.6 °F).

At the Victoria Gonzales weather station, daily temperatures rise above 30 °C (86 °F) on average less than one day per year and fall below 0 °C (32 °F) on average only ten nights per year. Victoria has recorded completely freeze-free winter seasons four times (in 1925–26, 1939–40, 1999–2000, and 2002–03). 1999 is the only calendar year on record without a single occurrence of frost. During this time the city went 718 days without freezing, starting on 23 December 1998 and ending 10 December 2000. The second longest frost-free period was a 686-day stretch covering 1925 and 1926, marking the first and last time the city has gone the entire season without dropping below 1 °C (34 °F).[30]

During the winter, the average daily high and low temperatures are 8 and 4 °C (46 and 39 °F), respectively. The summer months are also relatively mild, with an average high temperature of 20 °C (68 °F) and low of 11 °C (52 °F), although inland areas often experience warmer daytime highs. The highest temperature ever recorded at Victoria Gonzales was 39.8 °C (103.6 °F) on 28 June 2021;[31] The coldest temperature on record is −15.6 °C (3.9 °F) on 29 December 1968.[32] The average annual temperature varies from a high of 11.4 °C (52.5 °F) set in 2004 to a low of 8.6 °C (47.5 °F) set in 1916.[30]

Due to the rain shadow effect of the nearby Olympic Mountains, Victoria is the driest location on the British Columbia coast and one of the driest in the region. Average precipitation amounts in the Greater Victoria area range from 608 mm (23.9 in) at the Gonzales observatory in the City of Victoria to 1,124 mm (44.3 in) in nearby Langford.[33] The Victoria Airport, 25 km (16 mi) north of the city, receives about 45% more precipitation than the city proper. Regional average precipitation amounts range from as low as 406 mm (16.0 in) on the north shore of the Olympic Peninsula[34] to 3,505 mm (138.0 in) in Port Renfrew just 80 km (50 mi) away on the more exposed southwest coast of Vancouver Island. Vancouver measures 1,589 mm (62.6 in) annually and Seattle is at 952 mm (37.5 in).

One feature of Victoria's climate is its distinct dry and rainy seasons. Nearly two-thirds of the annual precipitation falls during the four wettest months, November to February. Precipitation in December, the wettest month (109 mm [4.3 in]) is nearly eight times as high as in July, the driest month (14 mm [0.55 in]). Victoria experiences the driest summers in Canada (outside of the extreme northern reaches of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut).[35]

Victoria averages just 26 cm (10 in) of snow annually, about half that of Vancouver. Roughly one third of winters see virtually no snow, with less than 5 cm (2.0 in) falling during the entire season. When snow does fall, it rarely lasts long on the ground. Victoria averages just two or three days per year with at least 5 cm (2.0 in) of snow on the ground. Every few decades Victoria receives very large snowfalls including the record breaking 100 cm (39 in) of snow that fell in December 1996. That amount places Victoria 3rd for biggest snowfall among major cities in Canada.

With 2,193 hours of bright sunshine annually during the last available measurement period, Victoria is effectively tied with Cranbrook as the sunniest city in British Columbia. In July 2013, Victoria received 432.8 hours of bright sunshine, which is the most sunshine ever recorded in any month in British Columbia history.[36]

Victoria's equable climate has also added to its reputation as the "City of Gardens". The city takes pride in the many flowers that bloom during the winter and early spring, including crocuses, daffodils, early-blooming rhododendrons, cherry and plum trees. Every February there is an annual "flower count" in what for the rest of the country and most of the province is still the dead of winter.

Due to its mild climate, Victoria and its surrounding area (southeastern Vancouver Island, Gulf Islands, and parts of the Lower Mainland and Sunshine Coast) are also home to many rare, native plants found nowhere else in Canada, including Quercus garryana (Garry oak), Arctostaphylos columbiana (hairy manzanita), and Canada's only broad-leaf evergreen tree, Arbutus menziesii (Pacific madrone). Many of these species exist here, at the northern end of their range, and are found as far south as southern California and parts of Mexico.

Non-native plants grown in Victoria include the cold-hardy palm Trachycarpus fortunei, which can be found in gardens and public areas of Victoria. One of these Trachycarpus palms stands in front of City Hall.[37]

| Climate data for Victoria (Gonzales Heights) Climate ID: 1018610; coordinates 48°24′47″N 123°19′30″W / 48.41306°N 123.32500°W; elevation: 69.5 m (228 ft); 1971–2000 normals, extremes 1898–present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.1 (62.8) |

17.4 (63.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.0 (80.6) |

31.6 (88.9) |

39.8 (103.6) |

36.0 (96.8) |

33.4 (92.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

25.3 (77.5) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

39.8 (103.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

15.9 (60.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

19.8 (67.6) |

20.1 (68.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.0 (41.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

7.6 (45.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

3.7 (38.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.2 (37.8) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.2 (6.4) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

3.9 (39.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 94.3 (3.71) |

71.7 (2.82) |

46.5 (1.83) |

28.5 (1.12) |

25.8 (1.02) |

20.7 (0.81) |

14.0 (0.55) |

19.7 (0.78) |

27.4 (1.08) |

51.2 (2.02) |

98.9 (3.89) |

108.9 (4.29) |

607.6 (23.92) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 85.2 (3.35) |

68.1 (2.68) |

45.3 (1.78) |

28.5 (1.12) |

25.8 (1.02) |

20.7 (0.81) |

14.0 (0.55) |

19.7 (0.78) |

27.4 (1.08) |

51.1 (2.01) |

95.5 (3.76) |

101.9 (4.01) |

583.1 (22.96) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 9.7 (3.8) |

3.5 (1.4) |

1.1 (0.4) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.0) |

4.1 (1.6) |

7.8 (3.1) |

26.3 (10.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 17.0 | 15.4 | 13.6 | 10.4 | 9.0 | 7.1 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 7.9 | 11.9 | 16.1 | 17.5 | 135.6 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 14.6 | 14.3 | 12.9 | 10.4 | 9.0 | 7.1 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 7.9 | 11.9 | 15.3 | 16.1 | 129.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 2.6 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 7.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 74.1 | 93.7 | 149.5 | 201.5 | 266.6 | 273.8 | 327.8 | 297.3 | 204.1 | 153.4 | 83.1 | 68.7 | 2,193.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 27.1 | 32.6 | 40.6 | 49.2 | 56.6 | 56.9 | 67.5 | 66.9 | 53.9 | 45.6 | 29.9 | 26.4 | 46.1 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: Environment and Climate Change Canada[38][39][40][41][42][32][43][44] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[45] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for University of Victoria Climate ID: 1018598; coordinates 48°27′25″N 123°18′18″W / 48.45694°N 123.30500°W; elevation: 60.1 m (197 ft); 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1992–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

25.0 (77.0) |

28.8 (83.8) |

37.8 (100.0) |

37.6 (99.7) |

34.5 (94.1) |

29.3 (84.7) |

23.5 (74.3) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

37.8 (100.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.5 (47.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.6 (51.1) |

8.6 (47.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

6.3 (43.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.0 (55.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

17.8 (64.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.6 (38.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

4.3 (39.7) |

5.8 (42.4) |

8.1 (46.6) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.0 (53.6) |

11.9 (53.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.3 (45.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

3.6 (38.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.7 (10.9) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

5.2 (41.4) |

6.2 (43.2) |

7.3 (45.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

−7.4 (18.7) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

| Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada[46][47][48][49]

</ref>[50] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for North Saanich (Victoria International Airport) WMO ID: 1018620; coordinates 48°38′50″N 123°25′33″W / 48.64722°N 123.42583°W; elevation: 19.5 m (64 ft); 1981-2010 normals, extremes 1940-present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high humidex | 16.4 | 17.1 | 20.9 | 26.1 | 33.6 | 42.6 | 39.6 | 36.8 | 34.7 | 27.0 | 20.0 | 17.7 | 42.6 |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.1 (61.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

26.3 (79.3) |

31.5 (88.7) |

39.4 (102.9) |

36.3 (97.3) |

34.4 (93.9) |

31.1 (88.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.1 (61.0) |

39.4 (102.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.9 (62.4) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.4 (72.3) |

19.6 (67.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

7.0 (44.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

5.1 (41.2) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.8 (62.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.4 (43.5) |

4.0 (39.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

1.3 (34.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

7.2 (45.0) |

9.8 (49.6) |

11.3 (52.3) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

5.7 (42.3) |

3.0 (37.4) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.6 (42.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.6 (3.9) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

2.1 (35.8) |

4.1 (39.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−13.3 (8.1) |

−14.4 (6.1) |

−15.6 (3.9) |

| Record low wind chill | −19.0 | −24.0 | −14.0 | −7.0 | −5.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −9.0 | −19.0 | −25.0 | −25.0 |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 143.2 (5.64) |

89.3 (3.52) |

78.4 (3.09) |

47.9 (1.89) |

37.5 (1.48) |

30.6 (1.20) |

17.9 (0.70) |

23.8 (0.94) |

31.1 (1.22) |

88.1 (3.47) |

152.6 (6.01) |

142.5 (5.61) |

882.9 (34.76) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 132.8 (5.23) |

83.0 (3.27) |

75.2 (2.96) |

47.5 (1.87) |

37.5 (1.48) |

30.6 (1.20) |

17.9 (0.70) |

23.8 (0.94) |

31.1 (1.22) |

88.0 (3.46) |

148.4 (5.84) |

129.7 (5.11) |

845.3 (33.28) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 10.9 (4.3) |

6.3 (2.5) |

3.4 (1.3) |

0.4 (0.2) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.1) |

4.7 (1.9) |

13.7 (5.4) |

39.7 (15.6) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 18.6 | 14.9 | 16.7 | 13.3 | 12.0 | 9.5 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 7.6 | 14.0 | 19.2 | 18.6 | 155.1 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 17.8 | 14.3 | 16.5 | 13.3 | 12.0 | 9.5 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 7.6 | 14.0 | 18.7 | 17.6 | 151.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 2.0 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 2.2 | 8.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 78.2 | 70.1 | 66.0 | 60.3 | 59.5 | 57.5 | 55.9 | 56.7 | 60.0 | 69.3 | 77.4 | 79.4 | 65.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 70.8 | 95.5 | 145.3 | 191.3 | 241.5 | 251.7 | 318.1 | 297.5 | 228.6 | 136.9 | 72.8 | 58.9 | 2,108.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 26.0 | 33.3 | 39.5 | 46.7 | 51.2 | 52.2 | 65.4 | 66.9 | 60.3 | 40.7 | 26.2 | 22.7 | 44.3 |

| Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada[51][52] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1871 | 3,270 | — |

| 1881 | 5,925 | +81.2% |

| 1891 | 16,841 | +184.2% |

| 1901 | 20,816 | +23.6% |

| 1911 | 31,660 | +52.1% |

| 1921 | 38,727 | +22.3% |

| 1931 | 39,082 | +0.9% |

| 1941 | 42,907 | +9.8% |

| 1951 | 51,331 | +19.6% |

| 1961 | 54,941 | +7.0% |

| 1971 | 61,761 | +12.4% |

| 1981 | 64,379 | +4.2% |

| 1991 | 71,228 | +10.6% |

| 1996 | 73,504 | +3.2% |

| 2001 | 74,125 | +0.8% |

| 2006 | 78,057 | +5.3% |

| 2011 | 80,017 | +2.5% |

| 2016 | 85,792 | +7.2% |

| 2021 | 91,867 | +7.1% |

| [53][54] | ||

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Victoria had a population of 91,867 living in 49,222 of its 53,070 total private dwellings, a change of 7.1% from its 2016 population of 85,792. With a land area of 19.45 km2 (7.51 sq mi), it had a population density of 4,723.2/km2 (12,233.1/sq mi) in 2021.[5] Victoria is one of the most gender diverse cities in Canada, with approximately 0.75% of residents identifying as transgender or non-binary in the 2021 Statistics Canada Census of Population.[55]

At the census metropolitan area (CMA) level in the 2021 census, the Victoria CMA had a population of 397,237 living in 176,676 of its 186,674 total private dwellings, a change of 8% from its 2016 population of 367,770. With a land area of 695.29 km2 (268.45 sq mi), it had a population density of 571.3/km2 (1,479.7/sq mi) in 2021.[6]

Victoria is known for its disproportionately large retiree population. Some 23.4 percent of the population of Victoria and its surrounding area are over 65 years of age, which is higher than the overall Canadian distribution of over 65 year-olds in the population (19%).[56] A historically popular cliché refers to Victoria as the home of "the newly wed and nearly dead".[57]

Ethnic origins

_a_Kwakwaka'wakw_big_house.jpg.webp)

| Panethnic group |

2021[58] | 2016[59] | 2011[60] | 2006[61] | 2001[62] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| European[lower-alpha 2] | 68,665 | 78.13% | 65,500 | 80.22% | 63,665 | 83.74% | 63,425 | 84.13% | 62,425 | 87.2% |

| East Asian[lower-alpha 3] | 4,645 | 5.29% | 4,715 | 5.77% | 3,720 | 4.89% | 4,360 | 5.78% | 3,465 | 4.84% |

| Indigenous | 4,365 | 4.97% | 3,780 | 4.63% | 3,375 | 4.44% | 2,835 | 3.76% | 2,180 | 3.05% |

| Southeast Asian[lower-alpha 4] | 3,120 | 3.55% | 2,420 | 2.96% | 1,615 | 2.12% | 1,505 | 2% | 930 | 1.3% |

| South Asian | 2,540 | 2.89% | 1,750 | 2.14% | 1,160 | 1.53% | 1,015 | 1.35% | 975 | 1.36% |

| African | 1,510 | 1.72% | 1,130 | 1.38% | 850 | 1.12% | 1,070 | 1.42% | 830 | 1.16% |

| Middle Eastern[lower-alpha 5] | 1,125 | 1.28% | 1,020 | 1.25% | 630 | 0.83% | 325 | 0.43% | 245 | 0.34% |

| Latin American | 1,120 | 1.27% | 765 | 0.94% | 505 | 0.66% | 495 | 0.66% | 405 | 0.57% |

| Other[lower-alpha 6] | 800 | 0.91% | 580 | 0.71% | 505 | 0.66% | 360 | 0.48% | 125 | 0.17% |

| Total responses | 87,890 | 95.67% | 81,650 | 95.17% | 76,025 | 95.01% | 75,390 | 96.58% | 71,590 | 96.58% |

| Total population | 91,867 | 100% | 85,792 | 100% | 80,017 | 100% | 78,057 | 100% | 74,125 | 100% |

- Note: Totals greater than 100% due to multiple origin responses.

| Ethnic Origin[58] | Population (2021)[lower-alpha 7] | Proportion[lower-alpha 8] |

|---|---|---|

| English | 26,790 | 30.5% |

| Scottish | 21,660 | 24.6% |

| Irish | 18,205 | 20.7% |

| German | 11,540 | 13.1% |

| French n.o.s | 8,300 | 9.4% |

| Canadian | 7,335 | 8.3% |

| British Isles, n.o.s.[lower-alpha 9] | 5,785 | 6.6% |

| Ukrainian | 4,455 | 5.1% |

| Dutch (Netherlands) | 4,030 | 4.6% |

| Chinese | 3,285 | 3.7% |

| Polish | 3,240 | 3.7% |

| Welsh | 3,210 | 3.7% |

| Norwegian | 3,030 | 3.4% |

| Italian | 3,205 | 3.6% |

| European n.o.s | 2,410 | 2.7% |

| Filipino | 2,255 | 2.6% |

| Russian | 2,195 | 2.5% |

| Swedish | 2,070 | 2.4% |

| American | 2,025 | 2.3% |

| Caucasian (White) n.o.s | 1,940 | 2.2% |

| East Indian | 1,790 | 2.0% |

| Métis | 1,525 | 1.7% |

| First Nations n.o.s | 1,460 | 1.7% |

| Jewish | 1,405 | 1.6% |

| Danish | 1,385 | 1.6% |

| Hungarian (Magyar) | 1,250 | 1.4% |

| Austrian | 1,090 | 1.2% |

| Spanish | 1,015 | 1.2% |

| Japanese | 1,015 | 1.2% |

| French Canadian | 1,085 | 1.2% |

- Note: These categories are those used by Statistics Canada.

Religion and spirituality

According to the 2021 census, the majority of the population of Victoria described themselves as irreligious (63.4%).[58] Over 25% of Victoria residents are Christian, with the second largest religious group being Muslim (1.9%). A similar proportion of residents are Buddhist (1.4%) or Jewish (1.1%). Hinduism, Sikhism and Indigenous Spirituality make up under 1% of other groups.

| Religious group | 2021[58] | 2011[60] | 2001[62] | 1991[63] | 1944[64]: 131–132 [53] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Christian | 24,930 | 28.37% | 28,270 | 37.19% | 37,195 | 51.96% | 43,425 | 63.17% | ||

| Muslim | 1,690 | 1.92% | 860 | 1.13% | 565 | 0.79% | 145 | 0.21% | ||

| Buddhist | 1,220 | 1.39% | 1,235 | 1.62% | 1,335 | 1.86% | 655 | 0.95% | ||

| Jewish | 960 | 1.09% | 550 | 0.72% | 595 | 0.83% | 325 | 0.47% | ||

| Hindu | 670 | 0.76% | 310 | 0.41% | 150 | 0.21% | 115 | 0.17% | ||

| Sikh | 420 | 0.48% | 315 | 0.41% | 300 | 0.42% | 350 | 0.51% | 338 | 0.77% |

| Indigenous spirituality | 255 | 0.29% | 90 | 0.12% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Other religion | 1,990 | 2.26% | 1,660 | 2.18% | 1,025 | 1.43% | 700 | 1.02% | ||

| Irreligious | 55,750 | 63.43% | 42,735 | 56.21% | 30,425 | 42.5% | 23,025 | 33.5% | ||

| Total responses | 87,890 | 95.67% | 76,025 | 95.01% | 71,590 | 96.58% | 68,740 | 96.51% | 44,068 | |

Neighbourhoods

The following is a list of neighbourhoods in the City of Victoria, as defined by the city planning department.[65] For a list of neighbourhoods in other area municipalities, see Greater Victoria, or the individual entries for those municipalities.

Informal neighbourhoods include:

Homelessness

A point-in-time homeless count was conducted by volunteers between March 11 and March 12, 2020, that counted at least 1,523 homeless that night.[66][67] The homeless count is considered an underestimate due to the hidden homeless that may be couch surfing or have found somewhere to stay that is not on the street or homeless shelters.[67] The first homeless count was conducted in January 2005 by the Victoria Cool Aid Society and counted a homeless population of approximately 700 individuals.[68]

Like many west coast cities in North America the homeless population is both concentrated in specific areas (parts of Pandora avenue in Victoria) and is often outside due to milder climates that make homelessness more visible year-round.

The 2020 point-in-time homeless count found 35% respondents identified as being Indigenous. This is over representative in the homeless population as only 4.7% of the overall population of Victoria identify as Indigenous.[69]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many homeless people sheltered in camping tents within the city's parks and some roadside greenspaces, including in Beacon Hill Park.[70] In March 2021, city council reinstated a bylaw prohibiting daytime camping in parks, and with support from the provincial government, pledged to find indoor accommodation for all those camping in parks.[71][72][73] Homeless campers from parks and other public spaces were housed temporarily in motels, the Save-on-Foods arena and a tiny home village on a portion of the Royal Athletic Park's parking lot.[74][75][76][77]

Economy

The city's chief industries are technology, tourism, education, federal and provincial government administration and services.[78] Other nearby employers include the Canadian Forces (the Township of Esquimalt is the home of the Pacific headquarters of the Royal Canadian Navy), and the University of Victoria (in the municipalities of Oak Bay and Saanich) and Camosun College in Saanich (which have over 33,000 faculty, staff and students combined). Other sectors of the Greater Victoria area economy include: investment and banking, online book publishing, various public and private schools, food products manufacturing, light aircraft manufacturing (in North Saanich), technology products, various high tech firms in pharmaceuticals and computers, engineering, architecture and telecommunications.

Employment by industry

The city's employment has 164,000 (87%) of workers in the service sector.[79] Top segments include health care and social assistance (28,900; 15.3%), public administration (27,800; 14.7 %), wholesale and retail trade (24,100; 12.7%), professional, scientific and technical services (19,800; 10.4%), educational services (15,000; 7.9%) and accommodation and food services (10,100; 5.3%). The goods-producing sector is dominated by construction (16,000; 8.4%) and manufacturing (6,900; 3.6%).

Retail

There are three major shopping malls in the City of Victoria, including the Bay Centre, Hillside Shopping Centre, and Mayfair Shopping Centre. Mayfair, one of the first major shopping centres in Victoria, first opened as an outdoor strip mall on 16 October 1963 with 27 stores.[80][81] It was built on the site of a former brickyard in the Maywood district, a then-semi-rural area in the northern part of Victoria.[81][82] Woodward's was Mayfair's original department store anchor upon the mall's opening.[81][83]

Mayfair was enclosed and renovated into an indoor mall in 1974.[84][85] The mall underwent three later expansions in 1984 (with the addition of Consumers Distributing), 1985 (expansion of the mall food court) and a major expansion in 1990 that saw the addition of more retail space.[84] The Bay (now Hudson's Bay) replaced Woodward's as Mayfair's department store anchor in 1993 following Hudson's Bay Company's acquisition of the Woodward's chain.[86] The mall was more recently renovated in 2019.[87] Mayfair now offers over 100 stores and services including Hudson's Bay.[88] It has 42,197.8 m2 (454,213 sq ft) of retail space and it also provides customers with rooftop parking.[89]

Technology industry

Advanced technology is Victoria's largest revenue-producing private industry with $3.15 billion in annual revenues generated by more than 880 tech companies that have over 15,000 direct employees.[90] The annual economic impact of the sector is estimated at more than $4.03 billion per year.[90] With three post-secondary institutions in Saanich, eight federal research labs in the region, and Canada's Pacific Navy Base in Esquimalt, Victoria relies heavily upon the neighbouring communities for economic activity and as employment hubs. The region has many of the elements required for a strong technology sector, including Canada's highest household internet usage.[91] Over a hundred technology, software and engineering companies have an office in Victoria.[92]

Tourism

Victoria is a major tourism destination with over 3.5 million overnight visitors per year who add more than a billion dollars to the local economy.[93] As well, over 500,000 daytime visitors arrive via cruise ships which dock at Ogden Point near the city's Inner Harbour. Many whale watching tour companies operate from this harbour due to the whales often present near its coast. The city is also close to Canadian Forces Base Esquimalt, the Canadian Navy's primary Pacific Ocean naval base.

Downtown Victoria also serves as Greater Victoria's regional downtown, where many night clubs, theatres, restaurants and pubs are clustered, and where many regional public events occur. Canada Day fireworks displays, Symphony Splash, and many other music festivals and cultural events draw tens of thousands of Greater Victorians and visitors to the downtown core. The Rifflandia and Electronic Music Festival are other music events that draw crowds to the downtown core. Victoria relies upon neighbouring communities for many recreational opportunities including ice rinks in Oak Bay and Saanich. Victoria has one small public pool (Crystal Pool) and many residents use larger and newer pool facilities in Oak Bay, and Saanich (Commonwealth Pool and Gordon Head Pool).

The city and metro region has hosted high-profile sports events including the 1994 Commonwealth Games which hosted track events at the Saanich-Oak Bay based University of Victoria and the Saanich Commonwealth Pool, the 2009 Scotties Tournament of Hearts, the 2005 Ford World Men's Curling Championship tournament, and 2006 Skate Canada. Victoria co-hosted the 2007 FIFA U-20 World Cup at Royal Athletic Park, and is the venue for the Bastion Square Grand Prix Criterium road cycling race. The city is also a destination for conventions, meetings, and conferences, including a 2007 North Atlantic Treaty Organization military chief of staff meeting held at the Hotel Grand Pacific. Every year, the Swiftsure International Yacht Race attracts boaters from around the world to participate in the boat race in the waters off of Vancouver Island, and the Victoria Dragon Boat Festival brings over 90 teams from around North America. The Tall Ships Festival brings sailing ships to the city harbour. Victoria also hosts the start of the Vic-Maui Yacht Race, the longest offshore sailboat race on the West Coast.

The Port of Victoria consists of three parts, the Outer Harbour, used by deep sea vessels, the Inner and Upper Harbours, used by coastal and industrial traffic. It is protected by a breakwater with a deep and wide opening. The port is a working harbour, tourist attraction and cruise destination. Esquimalt Harbour is also a well-protected harbour with a large graving dock and shipbuilding and repair facilities.

Arts and Culture

The Victoria Symphony, led by Christian Kluxen, performs at the Royal Theatre and the Farquhar Auditorium of the Saanich-Oak Bay sited University of Victoria from September to May. Every BC Day weekend, the Symphony mounts Symphony Splash, an outdoor event that includes a performance by the orchestra sitting on a barge in Victoria's Inner Harbour. Streets in the local area are closed, as each year approximately 40,000 people attend a variety of concerts and events throughout the day. The event culminates with the Symphony's evening concert, with Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture as the grand finale, complete with cannon fire from Royal Canadian Sea Cadet Gunners from HMCS QUADRA, a pealing carillon and a fireworks display to honour BC Day. Pacific Opera Victoria, Victoria Operatic Society, Victoria Philharmonic Choir, Canadian Pacific Ballet and Ballet Victoria stage two or three productions each year at the Macpherson or Royal Theatres.

Theatre

The Bastion Theatre, a professional dramatic company, functioned in Victoria through the 1970s and 1980s and performed high quality dramatic productions but ultimately declared bankruptcy in 1988.[94] Reborn as The New Bastion Theatre in 1990 the company operated for five more years before closing operations in 1996.[95]

The Belfry Theatre started in 1974 as the Springridge Cultural Centre in 1974. The venue was renamed the Belfry Theatre in 1976 as the company began producing its own shows. The Belfry's mandate is to produce contemporary plays with an emphasis on new Canadian plays. Other regional theatre venues include: the University of Victoria Phoenix Theatre;[96] The Roxy Theatre, home of the Blue Bridge Repertory Theatre company;[97] Kaleidoscope Theatre [98] and Intrepid Theatre Company,[99] producers of the Victoria Fringe Theatre Festival and The Uno Festival of Solo Performance.

The only Canadian Forces Primary Reserve brass/reed band on Vancouver Island is in Victoria. The 5th (British Columbia) Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery Band traces its roots back to 1864, making it the oldest, continually operational military band west of Thunder Bay, Ontario. Its mandate is to support the island's military community by performing at military dinners, parades and ceremonies, and other events. The band performs weekly in August at Fort Rodd Hill National Historic Site where the Regiment started manning the guns of the fort in 1896, and also performs every year at the Cameron Bandshell at Beacon Hill Park.

The annual multi-day Rifflandia Music Festival is one of Canada's largest modern rock and pop music festivals.

Films set in Victoria

Due to the proximity to Vancouver and a 6% distance location tax credit, Victoria is used as a filming location for many films, television series, and television movies. Some of these films include X2, X-Men: The Last Stand, In the Land of Women, White Chicks, Scary Movie, Final Destination, Excess Baggage and Bird on a Wire. Television series such as Smallville, The Dead Zone and Poltergeist: The Legacy were also filmed there.

Victoria-area artists and writers

Canadian director Atom Egoyan was raised in neighbouring Saanich. Actors Cameron Bright (Ultraviolet, X-Men: The Last Stand, Thank You for Smoking, New Moon) and Ryan Robbins (Stargate Atlantis, Battlestar Galactica, Sanctuary) were born in Victoria. Actor Cory Monteith from the television series Glee was raised in Victoria. Actor, artist, and athlete Duncan Regehr of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine was raised in the region. Artist, art magazine publisher and jazz saxophonist Noah Becker of Whitehot Magazine has been a long time Victoria resident.

Nobel laureate Alice Munro lived in Victoria during the years when she published her first story collections and co-founded Munro's Books. Victoria resident Stanley Evans has written a series of mysteries featuring a Coast Salish character, Silas Seaweed, who works as an investigator with the Victoria Police Department. Other Victoria writers include Kit Pearson, Esi Edugyan, Robert Wiersema, W. D. Valgardson, Elizabeth Louisa Moresby, Madeline Sonik, Jack Hodgins, Dave Duncan, Bill Gaston, David Gurr, Ken Steacy, Sheryl McFarlane, Carol Shields and Patrick Lane. Gayleen Froese's 2005 novel Touch is set in Victoria. The comedy troupe LoadingReadyRun is based in Victoria.

Victoria-area musicians

A number of well-known musicians and bands are from the Victoria area, including Nelly Furtado, David Foster, The Moffatts, Frog Eyes, Johnny Vallis, Jets Overhead, Bryce Soderberg, Armchair Cynics, Nomeansno, The New Colors, Wolf Parade, The Racoons, Tal Bachman, Dayglo Abortions, Hot Hot Heat, Aidan Knight and Noah Becker.

Attractions

.jpg.webp)

In the heart of downtown are the British Columbia Parliament Buildings, The Empress Hotel, Victoria Police Department Station Museum, the gothic Christ Church Cathedral, and the Royal British Columbia Museum/IMAX National Geographic Theatre, with large exhibits on local Aboriginal peoples, natural history, and modern history, along with travelling international exhibits. In addition, the heart of downtown also has the Maritime Museum of British Columbia, Emily Carr House, Victoria Bug Zoo, and Market Square. The oldest (and most intact) Chinatown in Canada is within downtown and includes the Chinese Public School built in 1909, and some cultural items and pictures displayed at the Pandora avenue entrances to Market Square.[100] The Art Gallery of Greater Victoria is close to downtown in the Rockland neighbourhood several city blocks from Craigdarroch Castle built by industrialist Robert Dunsmuir and Government House, the official residence of the Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia.

Numerous other buildings of historic importance or interest are also in central Victoria, including: the 1845 St. Ann's Schoolhouse; the 1852 Helmcken House built for Victoria's first doctor; the 1863 Congregation Emanu-El, the oldest synagogue in continuous use in Canada; the 1865 Angela College built as Victoria's first Anglican Collegiate School for Girls, now housing retired nuns of the Sisters of St. Ann; the 1871 St. Ann's Academy built as a Catholic school; the 1874 Church of Our Lord, built to house a breakaway congregation from the Anglican Christ Church cathedral; the 1890 St. Andrew's Presbyterian Church;[101] the 1890 Metropolitan Methodist Church (now the Victoria Conservatory of Music), [102] which is publicly open for faculty, student, and guest performances, also acts as Camosun College Music Department; the 1892 St. Andrew's Cathedral; and the 1925 Crystal Gardens, originally a saltwater swimming pool, restored as a conservatory and most recently a tourist attraction called the B.C. Experience, which closed down in 2006.

Downtown Victoria is a very walkable area with many midblock crosswalks, an expanding central pedestrian street,[103] public squares, and alleys that are predominantly spaces for pedestrians.[104] Fan Tan alley is the narrowest commercial street in North America and runs between Pandora avenue and Fisgard street in Victoria's Chinatown.[104] Dragon alley is also located in Chinatown and is a mix of commercial and residential units, located between Fisgard and Herald streets.[105] Theatre alley was rebuilt in a newer condo construction in Chinatown and is a narrow alley that winds between Pandora avenue and Fisgard street just west of Fan Tan alley, but it does not include direct access to any commercial businesses.[106] Waddington alley is uniquely paved with wooden blocks located between Yates and Johnson streets.[107] Trounce alley is a small commercial alley located between Government and Broad streets.[108][109]

Beacon Hill Park is the central city's main urban green space. Its area of 75 ha (190 acres) adjacent to Victoria's southern shore includes numerous playing fields, manicured gardens, exotic species of plants and animals such as wild peacocks, a petting zoo, and views of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Olympic Mountains in Washington across it. The sport of cricket has been played in Beacon Hill Park since the mid-19th century.[110] Each summer, the City of Victoria presents dozens of concerts at the Cameron Band Shell in Beacon Hill Park.[111]

The extensive system of parks in Victoria also includes a few areas of natural Garry oak meadow habitat, an increasingly scarce ecosystem that once dominated the region.[112]

Private gardens that are open to the public with sometimes limited opening hours are located throughout the city and offer access at low or no cost to visitors, they include the rose garden next to the Empress Hotel, the Government House Gardens on the grounds of the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia's house (also known as Government House) on Rockland Road,[113] and Abkahazi Garden on Fairfield Road.[114]

Dallas Road is a waterfront trail and road with 7.1 km[115] to walk, run, bike or drive. Clover Point is its main rest area with benches, lounge chairs, picnic tables and a public washroom.[116][117]

The David Foster Harbour Pathway is a predominantly a pedestrian pathway that meanders around the inner harbour between the southern start at Ogden point by the cruise ship terminal and Rock Bay at its northern terminus.[118] The pathway has some disconnected sections that are expected to be connected with redevelopments along the pathway near the Johnson street bridge.[119] When completed the David Foster Harbour Pathway is expected to extend over 5 kilometres in length.[118]

Outside the city

CFB Esquimalt navy base, in the adjacent municipality of Esquimalt, has a base museum dedicated to naval and military history, in the Naden part of the base.

North of the city on the Saanich Peninsula are the marine biology Shaw Ocean Discovery Centre, Butchart Gardens in Brentwood Bay, one of the biggest tourist and local resident attractions on Vancouver Island, as well as the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, part of the National Research Council of Canada, Victoria Butterfly Gardens and Centre of the Universe planetarium.[120]

Sports and recreation

Victoria's climate, location and variety of facilities make it ideal for many recreational activities including rock climbing, hiking, kayaking, golf, water sports, informal team sports and jogging.

Victoria is also known as the Cycling Capital of Canada,[121] with hundreds of kilometres of bicycle paths, bike lanes and bike routes in the city, including the Galloping Goose Regional Trail. There are mountain biking trails at Mount Work Regional Park in the neghbour community The District of Highlands,[122] and Victoria is quickly becoming a bike tourism destination.[123] Cycling advocacy groups including Greater Victoria Cycling Coalition (GVCC) and the Bike to Work Society have worked to improve Victoria's cycling infrastructure and facilities, and to make cycling a viable transportation alternative, attracting 5% of commuters in 2005.[124]

Greater Victoria also has a rich motorsports history, and was home to a 4/10ths mile oval race track called Western Speedway in the nearby City of Langford. Opened in 1954, Western Speedway was the oldest speedway in western Canada, and featured stock car racing, drag racing, demolition derbies and other events. Western Speedway was also home to the Victoria Auto Racing Hall of Fame and Museum.

The Greater Victoria area also serves as a headquarters for Rugby Canada, based out of Starlight Stadium in Langford, as well as a headquarters for Rowing Canada, based out of Victoria City Rowing Club at Elk Lake in Saanich. The Greater Victoria Sports Hall of Fame is at the Save-on-Foods Memorial Centre, and features numerous displays and information on the sporting history of the city.

The major sporting and entertainment complex, for Victoria and Vancouver Island Region, is the Save-On-Foods Memorial Centre arena. It replaced the former Victoria Memorial Arena, which was constructed by efforts of World War II veterans as a monument to fallen comrades. World War I, World War II, Korean War, and other conflict veterans are also commemorated. Fallen Canadian soldiers in past, present, and future wars and/or United Nations, NATO missions are noted, or will be noted by the main lobby monument at the Save-On-Foods Memorial Centre. The arena was the home of the ECHL (formerly known as the East Coast Hockey League) team, Victoria Salmon Kings, owned by RG Properties Limited, a real estate development firm that built the Victoria Save On Foods Memorial Centre, and Prospera Place Arena in Kelowna. The arena is the home of the Victoria Royals Western Hockey League (WHL) team that replaced the Victoria Salmon Kings (ECHL).

International events

Victoria has also been a destination for numerous high-profile international sporting events. It co-hosted the 1994 Commonwealth Games with Saanich and Oak Bay and the 2005 Ford World Men's Curling Championship. The 2007 FIFA U-20 World Cup was co-hosted by Victoria along with five other Canadian cities; (Burnaby, Toronto, Edmonton, Ottawa, Montreal). Victoria was also the first city location of the cross Canada 2010 Winter Olympics torch relay that occurred before the start of the 2010 Winter Olympics. Victoria co-hosted the 2019 World Junior Ice Hockey Championships along with Vancouver, British Columbia. Victoria was one of four host cities for the 2020 FIBA Men's Olympic Qualifying Tournaments in June 2020.

Sports teams

The city has also been home to numerous high-profile sports teams in its history. The Victoria Cougars are perhaps the most famous sports franchise the city has known, existing as members of several professional leagues from 1911 to 1926, and again from 1949 to 1961. The Cougars won the Stanley Cup as members of the WCHL in 1925 after defeating the Montreal Canadiens three games to one in a best-of-five final. The Cougars were reincarnated in 1971 as a major junior hockey team in the Western Hockey League, before they moved to Prince George to become the Prince George Cougars. Today, the Cougars name and legacy continue in the form of the Junior 'B' team that plays in the Vancouver Island Junior Hockey League. Minor professional hockey returned to Victoria in the form of the Victoria Salmon Kings, which played in the ECHL from 2004 to 2011, and were a minor league affiliate of the Vancouver Canucks. In baseball, Victoria was once home of the Victoria Athletics of the Western International League, a Class 'A' minor league baseball affiliate of the New York Yankees. The Victoria region's newest sports team is Pacific FC of the Canadian Premier League. Pacific FC play their home matches at Starlight Stadium in Langford.

Victoria has been home to many accomplished athletes that have participated in professional sports or the Olympics. Notable professional athletes include basketball Hall of Famer Steve Nash, twice Most Valuable Player in the National Basketball Association, who grew up in Victoria and played youth basketball at St. Michael's University School in Saanich and Mount Douglas Secondary School in Saanich. Furthermore, there are several current NHL hockey players from Greater Victoria, including brothers Jamie Benn and Jordie Benn of the Dallas Stars and Toronto Maple Leafs, respectively who grew up in North Saanich; Tyson Barrie of the Edmonton Oilers, and Matt Irwin of the Washington Capitals. Current Boston Red Sox pitcher Nick Pivetta was born in Victoria and played summer collegiate baseball for the Victoria HarbourCats. Former professional racing cyclist and 2012 Giro d'Italia winner, Ryder Hesjedal was born in Victoria and still calls the city home. Victoria has also been home to many Olympic Games athletes, including multi-time medalists such as Silken Laumann, Ryan Cochrane, and Simon Whitfield.

Sports teams presently operating in Victoria include:

| Club | Sport | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pacific FC | Soccer | Canadian Premier League | Starlight Stadium, Langford |

| Victoria Royals | Ice hockey | Western Hockey League | Save on Foods Memorial Centre |

| Victoria HarbourCats | Baseball | West Coast League | Royal Athletic Park |

| UVic Vikes | Various | U Sports | Various, principally UVic (Saanich-Oak Bay) |

| Camosun Chargers | Various | Canadian Colleges Athletic Association | Various, principally Camosun College (Saanich) |

| Victoria Shamrocks | Box lacrosse | Western Lacrosse Association | The Q Centre |

| Victoria Grizzlies | Ice hockey | British Columbia Hockey League | The Q Centre |

| Westshore Rebels | Canadian football | Canadian Junior Football League | Starlight Stadium, Langford |

| Victoria Highlanders | Soccer | USL League Two | Centennial Stadium |

| Eves of Destruction | Roller Derby | Women's Flat Track Derby Association | Various |

Notable defunct teams that operated in Victoria include:

Infrastructure

The Jordan River Diversion Dam is Vancouver Island's main hydroelectric power station. It was built in 1911.[125]

The city's water is supplied by the Capital Regional District's Water Services Department from its Sooke Lake Reservoir. The lake is connected to a treatment plant at Japan Gulch by the 8.8 km (5.5 mi) Kapoor Tunnel. The lake water is very soft and requires no filtering. It is treated with chlorine, ammonia and ultraviolet light to control micro-organisms. [126] Until the tunnel was completed in 1967, water flowed from the lake through the circuitous, leaky and much smaller 44 km (27 mi) Sooke Flowline.

The Hartland landfill in Saanich is the waste disposal site for Greater Victoria area. Since 1985, it has been run by the Capital Regional District environmental services. It is on top of a hill, between Victoria and Sidney, at the end of Hartland Avenue (48°32′17″N 123°27′48″W / 48.53806°N 123.46333°W) There is a recycling centre, a sewer solid waste collection, hazardous waste collection, and an electricity generating station. This generating station now creates 1.6 megawatts of electricity, enough for 1,600 homes.[127] The site has won international environmental awards.[128] The CRD conducts public tours of the facility. It is predicted to be full by 2045.

As of December 15, 2020 the CRD announced that core municipalities within Greater Victoria no longer discharge screened wastewater into the Strait of Juan de Fuca.[129][130] The wastewater treatment facility was required to comply with federal regulations that forbid untreated discharge into waterways.[131] The wastewater treatment project included pump stations at Clover Point and Macaulay Point in addition to the wastewater treatment plant at McLoughlin Point and the residuals treatment facility at Hartland landfill.[129][132] The wastewater treatment plant serves Victoria, Esquimalt, Saanich, Oak Bay, View Royal, Langford, Colwood and the Esquimalt and Songhees First Nations.[129]

The Saanich Peninsula wastewater treatment plant serves North Saanich, Central Saanich and the Town of Sidney as well as the Victoria International Airport, the Institute of Ocean Sciences and the Tseycum and Pauquachin First Nations.[133] This is a secondary level treatment plant which produces Class A biosolids.[133]

Transportation

Air

Victoria International Airport in North Saanich has non-stop flights to and from Toronto, Seattle, Montreal (seasonal), select seasonal sun destinations, and many cities throughout Western Canada. Multiple scheduled helicopter and seaplane flights are available daily from Victoria Inner Harbour Airport to Vancouver International Airport, Vancouver Harbour, and Seattle.

Victoria is also home to the world's largest all-seaplane airline, Harbour Air.[134] Harbour air offers flights during daylight hours at least every 30 minutes between Victoria's inner harbour and Vancouver's downtown terminal or YVR south terminal. Harbour Air also operate scenic tour flights over the Victoria harbour and gulf islands area.[135]

Cycling

.jpg.webp)

Due to Victoria's mild year round weather with mostly rainy winters, commuting by bicycle is more enjoyable year-round compared to many other Canadian cities. For this reason, the Greater Victoria area has the highest rate of bicycle commuting to work of any census metropolitan area in Canada.[136][137][138] Greater Victoria also has an expanding system designed to facilitate cyclists, electrically assisted bicycles and other micromobility users via protected bike lanes on many roads, as well as separated multi-use paths for bicycles and pedestrians including the Galloping Goose Regional Trail, Lochside Regional Trail and the E&N rail trail. These multi-use trails are designed exclusively for foot traffic, cyclists, and micro-mobility users and pass through many communities in the Greater Victoria area, beginning at the downtown core and extending into areas such as Langford and Central and North Saanich.

Victoria is currently finishing a 32 kilometre protected bike lane network intended for all ages and abilities (AAA).[139] The first lane opened in Spring 2017 on Pandora Avenue, between Store Street and Cook Street in the downtown core[140] and provides an easy cycling connection across the Johnson Street Bridge to the Galloping Goose Trail and E&N rail trail. The second protected bike lane in the network opened on Fort Street on May 27, 2018.[141] The next two roads added to the downtown area bike network were Wharf and Humboldt streets, completed in 2019 and 2020 respectively,[142][143] with Vancouver Street and Graham/Jackson streets added to the AAA bike network in 2021.[144] The next round of streets upgraded starting in 2021 as "complete streets" with AAA cycling infrastructure included Richardson Street, Haultain Street, Government Street north of Pandora Avenue to Gorge Road, and finally Kimta Road connecting the network to the E&N rail trail.[145] Connector routes in the Fernwood and Oaklands neighbourhoods to the Vancouver Street lanes were also constructed starting in 2021, avoiding hills and adding safer pedestrian and cyclist crossings.[146] In 2022 the city constructed further AAA bicycle connections along Montreal street, Superior street, Government street (south, between Humboldt street and Dallas road), Fort street (between Cook street and up to the municipal border with Oak Bay), and Gorge Road (between Government street and up to the municipal border with Saanich).[147][148]

.jpg.webp)

Go By Bike Week,[149][150] previously called Bike to Work Week,[151][152][153] is a bi-annual event held in communities throughout greater Victoria, British Columbia. It is organized by Capital Bike,[154] a group created in 2021 by the merging of the Greater Victoria Cycling Coalition and Greater Victoria Bike to Work Society, and typically lasts one or two weeks. There is a large Spring event scheduled in late May every year, and again later during Fall typically in October. The original "Bike to Work Week" began in 1995 in Victoria and expanded to include other communities in BC through their local bicycle advocacy groups, all supported by the Bike to Work BC Society. The Bike to Work BC Society was formed in 2008 as a legal entity to run the event in other communities around BC, and was renamed the GoByBike BC Society[155] to encourage cycling beyond the scope of commuting. The behaviour change (public health) model, relying on research conducted by both the provincial and federal governments that identified barriers to cycling and reasons for choosing cycling, was applied in the original Bike to Work Week event as a way to accomplish the goal of recruiting employees to bicycle to work.[156] Since its inception, ridership in Go By Bike Week has steadily increased, and in 2017 over 7000 people participated in Greater Victoria.[157] The event aims to attract new riders, promote cycling for commuting, recreation, and general transportation, and advocate for expanding safe cycling networks with prizes, activities and free cycling skills workshops. Pop-up "Celebration Stations" are set up throughout Greater Victoria, which typically feature free snacks and local coffee for cyclists, bicycle repair stands, and local cycling-related vendors and advocacy groups. The events were cancelled during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, though individualized events were still promoted where participants could win prizes,[158] and in-person events resumed in 2022.[159]

Other cycling advocacy initiatives in the Greater Victoria area include the Victoria chapter of Cycling Without Age,[160][161] the Bike2Farm program[162] and several recreational cycling clubs.

Ferries

The CRD is served by several ferries with the Lower Mainland, Gulf Islands and the United States. BC Ferries provides service between Swartz Bay, located on the northern tip of the Saanich Peninsula, to Tsawwassen on the Lower Mainland for cars, bus, trucks, pedestrians and cyclists. The Coho ferry[163] operates as a car and pedestrian/cyclist ferry between the inner harbour of Victoria and Port Angeles, Washington. The Victoria Clipper is a pedestrian and cyclist-only (no vehicles) ferry which operates daily, year-round between downtown Seattle and the inner harbour of Victoria. The Washington State Ferries ran a ferry until 2020 for cars, pedestrians and cyclists between Friday Harbor, Orcas Island and Anacortes in Washington State from the port at Sidney, north of Victoria on the Saanich Peninsula.[164] However, the service was shut down during the COVID-19 pandemic and did not resume.[165] Washington State Ferries, citing crew and vessel shortages, estimates that it will not resume until at least 2030.[166]

Public transit

Local public transportation is run by the Victoria Regional Transit System, which is part of BC Transit. Since 2000, double-decker buses have been introduced to the fleet, and have become an icon for the city. Rider fare payments can be made in cash, monthly bus passes, disability yearly passes, day-passes purchased from the driver or tickets purchased from a store. As of April 1, 2016 bus drivers do not provide transfers as proof of payment. Transfers were a source of disagreement and delay on the bus, due to improper transfer use, and disagreements over expired transfers or transfers used for return trips.[167] Instead, a day-pass was added that can be purchased from the bus driver for $5, or two bus tickets (purchased from a retailer) for the equivalent of $4.50.[167] To improve bus reliability and reduce delays, a bike and bus priority lane was opened in 2014 during peak traffic periods with fines for motorists operating in the bus/bike lane who are not turning in the same block.[168] The dedicated bike and bus lane on Douglas street is being expanded from Downtown to near Uptown and may be changed to be restricted to only buses and bikes 24/7 rather than just during peak traffic periods depending on direction of travel.[169] Most buses operating in the Greater Victoria area have a bike rack installed at the front of the bus that can accommodate two bicycles.[170]

Rail

Passenger rail service previously operated by Via Rail provided a single daily return trip along between Victoria – Courtenay, along the eastern coast of Vancouver Island, to the cities of Nanaimo, Courtenay, and points between. The service was discontinued along this line indefinitely on 19 March 2011, due to needed track replacement work.[171][172] Prior to further inspection of the track, service along the segment between Nanaimo and Victoria was originally planned to resume on 8 April, but lack of funding has prevented any of the work from taking place and it is unclear when or if the service will resume.

Roads

Local roadways are not based on a grid system as they are in Vancouver or Edmonton, and many streets do not follow a straight line from beginning to end as they wind around hills, parks, coastlines, and historic neighbourhoods, often changing names two or three times.[173] There is no directional indication in street names that may be used in other cities with numbered roads where a street may run north–south or avenue may run east–west.[174]

The compact size of the city with few steep hills lends itself readily to smaller, fuel efficient alternatives to full size passenger cars, such as scooters, Smart Cars, motorcycles and electric bicycles. Victoria incentivizes the use of smaller modes of transport by offering smaller metered parking spaces in the downtown core specifically designated for small vehicles and motorcycles.[175] Rush hour traffic delays along the Trans-Canada Highway to western suburban municipalities (including Langford, Colwood, Sooke and Metchosin) is commonly referred to as the "Colwood Crawl".[176]

Victoria serves as the western terminus (Mile Zero) for Canada's Trans-Canada Highway, the longest national highway in the world. The Mile Zero marker is at the southernmost point of Douglas Street where it meets Dallas Road along the waterfront. The Mile Zero location includes a statue to honour Terry Fox.

Other transportation

Coach bus service between downtown Victoria and downtown Vancouver or the Vancouver International Airport, which includes the ferry fare is called the BC Ferries Connector run by Wilson's Transportation Limited. The coach bus travels on the ferry to Vancouver with separate trips for the bus to downtown and a bus to the Vancouver International Airport (YVR). Average travel time between the two cities is under 4 hours with an hour and half of that time spent on the ferry crossing.

Bus service from Victoria to points up island is run by Island Link Bus or Tofino Bus. Both bus services depart from the Victoria bus terminal at 700 Douglas Street, behind the Fairmont Empress Hotel and offer trips to destinations further up island and the west coast of the island.

Education

The city of Victoria lies entirely within the Greater Victoria School District. Victoria High School is the only public high school located within the municipal boundaries of the city of Victoria. Opened August 7, 1876, Victoria High School is the oldest High School in North America north of San Francisco and west of Winnipeg, Manitoba.[177] Many of the elementary schools in Victoria offer both French immersion and English programs of instruction. École Victor-Brodeur in Esquimalt serves as a dedicated school for Francophones.

In addition, there are several independent schools serving the Greater Victoria community, including the Chinese School in Chinatown, the Christ Church Cathedral School , Glenlyon Norfolk School, Lester B. Pearson United World College of the Pacific, St. Margaret's School , St. Michaels University School, St. Patrick's Elementary School.

Greater Victoria is served by three public post secondary educational institutions, listed by student population size below:

- University of Victoria (UVic), with 22,020 undergraduate and graduate students.[178] The University of Victoria is located within the boundaries of the District of Saanich and the District of Oak Bay.

- Camosun College, with 20,400 learners.[179] Camosun College has two campuses (Lansdowne and Interurban), both of which are located within the District of Saanich.

- Royal Roads University (RRU) with 4,748 full-time undergraduate and graduate students.[180] The Royal Roads University campus is located in Colwood.

A number of private career colleges are located in Victoria including the Justice Institute of British Columbia, Pacific Rim College, Sprott Shaw College and the Victoria College of Art.

Media

Victoria is served by a number of media outlets including the Times Colonist, an English-language daily; a variety of local print outlets; 12 radio stations, and 3 television stations: CHEK-DT (an independent station), CIVI-DT (a CTV 2 owned-and-operated station) and Shaw Spotlight.

Victoria is the only Canadian provincial capital without a local CBC Television station, owned-and-operated or affiliate, although it does host a small CBC Radio One (CBCV-FM) station at 780 Kings Road. The region is considered to be a part of the Vancouver television market, receiving most stations that broadcast from across the Strait of Georgia, including CBC Television, Ici Radio-Canada Télé, CTV, Global, Citytv and Omni owned-and-operated stations.

Notable people

- Tyson Barrie, hockey player, NHL Nashville Predators

- Jamie Benn, hockey player, NHL Dallas Stars

- Jordie Benn, hockey player, Swedish HockeyAllsvenskan Brynäs IF

- David Holmes Black, media proprietor, founder of Black Press

- Emily Carr, artist (1971-1945)

- Nikki Chooi, classical violinist

- Sir Arthur Currie, general (1875-1933)

- Don Drummond (economist), economist

- Esi Edugyan, writer

- Atom Egoyan, filmmaker

- Erin Fitzgerald, voice actress

- Billy Foster, racing driver (1937-1967)

- David Foster, music composer

- Nelly Furtado, singer and songwriter

- Rhonda Ganz, poet and illustrator

- Chelsea Green, professional wrestler

- Ryder Hesjedal, road cyclist and winner of the 2012 Giro d'Italia

- Matt Irwin, hockey player, AHL Abbotsford Canucks

- Jimbo (drag queen), drag artist and designer

- Gary Kershaw, racing driver

- Ed Kostenuk, racing driver (1925-1997)

- J. Fenwick Lansdowne, wildlife artist

- Silken Laumann, Olympic rower

- Hannah Maynard, photographer

- Cory Monteith, actor and musician (1982-2013)

- Alice Munro, short story writer

- Steve Nash, basketball player and 2x NBA MVP

- Rick O'Dell, racing driver

- Larry Pollard, racing driver

- Peter Pollen, politician and business man

- Bill Reid, artist and carver (1920-1998)

- Jack Shadbolt, artist (1909-1998)

- Carol Shields, writer

- Roy Smith, NASCAR racing driver (1944-2004)

- Spiritbox, heavy metal band

- Ross Surgenor, racing driver

- Ian Tyson, singer-songwriter (1933-2022)

- William Vickrey, economist and Nobel Laureate (1914-1996)

- Tudi Wiggins, actress

- Calum Worthy, actor

Twin Cities - Sister Cities

Victoria has three sister cities:[181]

As of March 4, 2022, Victoria City Council voted to suspend the city's relationship with Khabarovsk, Russia as a result of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[182]

Victoria also has Friendship City agreements with:

See also

- Dallasite, unofficial gemstone of Victoria, British Columbia

- Leaky condo crisis

- List of historic places in Victoria, British Columbia

- Monarchy in British Columbia

- Royal eponyms in Canada

- Old Victoria Custom House

- Victoria (disambiguation)#Places

Notes

- ↑ Climate data for Victoria was recorded at Gonzales Heights from August 1898 to present.

- ↑ Statistic includes all persons that did not make up part of a visible minority or an indigenous identity.

- ↑ Statistic includes total responses of "Chinese", "Korean", and "Japanese" under visible minority section on census.

- ↑ Statistic includes total responses of "Filipino" and "Southeast Asian" under visible minority section on census.

- ↑ Statistic includes total responses of "West Asian" and "Arab" under visible minority section on census.

- ↑ Statistic includes total responses of "Visible minority, n.i.e." and "Multiple visible minorities" under visible minority section on census.

- ↑ Included multiple responses

- ↑ does not total 100% because all figures are multiple responses

- ↑ "n.o.s." means "not otherwise specified"

References

- ↑ "British Columbia Regional Districts, Municipalities, Corporate Name, Date of Incorporation and Postal Address" (XLS). British Columbia Ministry of Communities, Sport and Cultural Development. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- ↑ "B.C. Transit drivers return to calling out stops on Victoria buses". Victoria News. Black Press. 6 May 2012. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ↑ Macionis, John J (2002). Society: The Basics. Upper Saddle River, N.J: Prentice Hall. p. 69. ISBN 9780131111646.

- ↑ "History Snapshot of Victoria, BC". City Of Victoria. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - Victoria, City (CY) [Census subdivision], British Columbia". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Profile table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population - Victoria [Census metropolitan area], British Columbia". Statistics Canada. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ↑ "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Victoria [Population centre], British Columbia and British Columbia [Province]". 2.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑ "Victoria". Geographical Names Data Base. Natural Resources Canada.

- ↑ "Table 36-10-0468-01 Gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, by census metropolitan area (CMA) (x 1,000,000)". Statistics Canada. 27 January 2017. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- ↑ "The 10 highest population densities among municipalities (census subdivisions) with 5,000 residents or more, Canada, 2016". Statistics Canada. 8 February 2017. Archived from the original on 20 April 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ↑ Gemme, Brigitte (November 2009). "Economic Impact of the Greater Victoria Technology Sector" (PDF). University of British Columbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

This report was commissioned by the Victoria Advanced Technology Council (VIATeC) and prepared by Brigitte Gemme, Ph.D. candidate at the University of British Columbia. The study was supported by the ACCELERATE BC (MITACS) internship programme. The Centre for Sustainability and Social Innovation and its director, professor James Tansey, generously hosted the author of the report during the internship. The author and VIATeC would also like to thank the Victoria technology sector organizations who took the time to participate in this study.

- ↑ "Quality of Life Index by City 2019". numbeo.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ↑ "Milestones: 1830–1860 - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "Ahead of #AllIn2019: A history of the area around Victoria". Community Foundations of Canada. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ W. Kaye Lamb, "The Founding of Fort Victoria," B.C Historical Quarterly, Vol. VII (April 1943), p. 88

- ↑ "City of Victoria – History". Archived from the original on 25 February 2006.

- ↑ "Douglas Treaties: 1850–1854" (PDF). Government of British Columbia – Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation. 28 November 2006. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ↑ Watts, R., 'Tsawout file claim to James Island; Assertion based on 1852 treaty signed by James Douglas', Times-Colonist (Victoria, B.C), 26 Jan 2018