| Victor Emmanuel II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Victor Emmanuel, c. 1861, by Disdéri | |||||

| King of Italy | |||||

| Reign | 17 March 1861 – 9 January 1878 | ||||

| Predecessor | Napoleon (1814) | ||||

| Successor | Umberto I | ||||

| Prime ministers | |||||

| King of Sardinia[lower-alpha 1] Duke of Savoy | |||||

| Reign | 23 March 1849 – 17 March 1861 | ||||

| Predecessor | Charles Albert | ||||

| Prime ministers | |||||

| Born | 14 March 1820 Palazzo Carignano, Turin, Kingdom of Sardinia | ||||

| Died | 9 January 1878 (aged 57) Quirinal Palace, Rome, Kingdom of Italy | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue see details... | |||||

| |||||

| House | Savoy-Carignano | ||||

| Father | Charles Albert of Sardinia | ||||

| Mother | Maria Theresa of Austria | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature | |||||

Victor Emmanuel II (Italian: Vittorio Emanuele II; full name: Vittorio Emanuele Maria Alberto Eugenio Ferdinando Tommaso di Savoia; 14 March 1820 – 9 January 1878) was King of Sardinia (also known as Piedmont-Sardinia) from 23 March 1849 until 17 March 1861,[lower-alpha 1] when he assumed the title of King of Italy and became the first king of an independent, united Italy since the 6th century, a title he held until his death in 1878. Borrowing from the old Latin title Pater Patriae of the Roman emperors, the Italians gave him the epithet of Father of the Fatherland (Italian: Padre della Patria).

Born in Turin as the eldest son of Charles Albert, Prince of Carignano, and Maria Theresa of Austria, he fought in the First Italian War of Independence (1848–1849) before being made King of Sardinia following his father's abdication. He appointed Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, as his Prime Minister, and he consolidated his position by suppressing the republican left. In 1855, he sent an expeditionary corps to side with French and British forces during the Crimean War; the deployment of Italian troops to the Crimea, and the gallantry shown by them in the Battle of the Chernaya (16 August 1855) and in the siege of Sevastopol led the Kingdom of Sardinia to be among the participants at the peace conference at the end of the war, where it could address the issue of the Italian unification to other European powers.[1] This allowed Victor Emmanuel to ally himself with Napoleon III, Emperor of France. France had supported Sardinia in the Second Italian War of Independence, resulting in liberating Lombardy from Austrian rule.

Victor Emmanuel supported the Expedition of the Thousand (1860–1861) led by Giuseppe Garibaldi, which resulted in the rapid fall of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in southern Italy. However, Victor Emmanuel halted Garibaldi when he appeared ready to attack Rome, still under the Papal States, as it was under French protection. In 1860, Tuscany, Modena, Parma and Romagna decided to side with Sardinia, and Victor Emmanuel then marched victoriously in the Marche and Umbria after the victorious Battle of Castelfidardo over the Papal forces. This led to his excommunication from the Catholic Church until 1878, just before his death in the same year. He subsequently met Garibaldi at Teano, receiving from him the control of southern Italy and becoming the first King of Italy on 17 March 1861.

In 1866, the Third Italian War of Independence allowed Italy to annex Veneto. In 1870, Victor Emmanuel also took advantage of the Prussian victory over France in the Franco-Prussian War to conquer the Papal States after the French withdrew. He entered Rome on 20 September 1870 and set up the new capital there on 2 July 1871. He died in Rome in 1878, and was buried in the Pantheon.

The Italian national Victor Emmanuel II Monument in Rome, containing the Altare della Patria, was built in his honour.

Biography

Victor Emmanuel was born as the eldest son of Carlo Alberto Prince of Carignano, and Maria Theresa of Austria. His father succeeded a distant cousin as King of Sardinia in 1831. He lived for some years of his youth in Florence and showed an early interest in politics, the military, and sports. In 1842, he married his cousin, Adelaide of Austria. He was styled as the Duke of Savoy prior to becoming King of Sardinia.

He took part in the First Italian War of Independence (1848–1849) under his father, King Charles Albert, fighting in the front line at the battles of Pastrengo, Santa Lucia, Goito and Custoza.[2]

He became King of Sardinia in 1849 when his father abdicated the throne, after being defeated by the Austrians at the Battle of Novara. Victor Emmanuel was immediately able to obtain a rather favourable armistice at Vignale by the Austrian imperial army commander, Radetzky. The treaty, however, was not ratified by the Piedmontese lower parliamentary house, the Chamber of Deputies, and Victor Emmanuel retaliated by firing his Prime Minister, Claudio Gabriele de Launay, replacing him with Massimo D'Azeglio. After new elections, the peace with Austria was accepted by the new Chamber of Deputies. In 1849, Victor Emmanuel also fiercely suppressed a revolt in Genoa, defining the rebels as a "vile and infected race of canailles."

In 1852, he appointed Count Camillo Benso of Cavour ("Count Cavour") as Prime Minister of Piedmont-Sardinia. This turned out to be a wise choice since Cavour was a political mastermind and a major player in the Italian unification in his own right. Victor Emmanuel II soon became the symbol of the "Risorgimento", the Italian unification movement of the 1850s and early 60s. [2] He was especially popular in the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia because of his respect for the new constitution and his liberal reforms.

Crimean War

Following Victor Emmanuel's advice, Cavour joined Britain and France in the Crimean War against Russia. Cavour was reluctant to go to war due to the power of Russia at the time and the expense of doing so. Victor Emmanuel, however, was convinced of the rewards to be gained from the alliance created with Britain and, more importantly, France.

After successfully seeking British support and ingratiating himself with France and Napoleon III at the Congress of Paris in 1856 at the end of the war, Count Cavour arranged a secret meeting with the French emperor. In 1858, they met at Plombières-les-Bains (in Lorraine), where they agreed that if the French were to help Piedmont in its war against Austria, which still reigned over the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia in northern Italy, France would be awarded Nice and Savoy.

Wars of Italian Unification

The Italo-French campaign against Austria in 1859 started successfully. However, sickened by the casualties of the war and worried about the mobilisation of Prussian troops, Napoleon III secretly made a treaty with Franz Joseph of Austria at Villafranca whereby Piedmont would only gain Lombardy. France did not as a result receive the promised Nice and Savoy, but Austria did keep Venetia, a major setback for the Piedmontese, in no small part because the treaty had been prepared without their knowledge. After several quarrels about the outcome of the war, Cavour resigned, and the king had to find other advisors. France indeed only gained Nice and Savoy after the Treaty of Turin was signed in March 1860, after Cavour had been reinstalled as Prime Minister, and a deal with the French was struck for plebiscites to take place in the Central Italian Duchies.

Later that same year, Victor Emmanuel II sent his forces to fight the papal army at Castelfidardo and drove the Pope into Vatican City. His success at these goals led him to be excommunicated from the Catholic Church until 1878 when it was lifted just before his death. Then, Giuseppe Garibaldi conquered Sicily and Naples, and Piedmont-Sardinia grew even larger. On 17 March 1861, the Kingdom of Italy was officially established and Victor Emmanuel II became its king.

Victor Emmanuel supported Giuseppe Garibaldi's Expedition of the Thousand (1860–1861), which resulted in the rapid fall of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in southern Italy. However, the king halted Garibaldi when he appeared ready to attack Rome, still under the Papal States, as it was under French protection. In 1860, through local plebiscites, Tuscany, Modena, Parma and Romagna decided to side with Piedmont-Sardinia. Victor Emmanuel then marched victoriously in the Marche and Umbria after the victorious battle of Castelfidardo (1860) over the Papal forces.

The king subsequently met with Garibaldi at Teano, receiving from him the control of southern Italy. Another series of plebiscites in the occupied lands resulted in the proclamation of Victor Emmanuel as the first King of Italy by the new Parliament of unified Italy, on 17 March 1861. He did not renumber himself after assuming the new royal title, however. Turin became the capital of the new state. Only Lazio, Veneto, and Trentino remained to be conquered.

Completion of the unification

In 1866 Victor Emmanuel allied himself with Prussia in the Third Italian War of Independence. Although not victorious in the Italian theatre, he managed to receive Veneto after the Austrian defeat in Germany. The British Foreign Secretary, Lord Clarendon, visited Florence in December 1867 and reported to London after talking to various Italian politicians: "There is universal agreement that Victor Emmanuel is an imbecile; he is a dishonest man who tells lies to everyone; at this rate, he will end up losing his crown and ruining both Italy and his dynasty."[3] In 1870, after two failed attempts by Garibaldi, he also took advantage of the Prussian victory over France in the Franco-Prussian War to capture Rome after the French withdrew. He entered Rome on 20 September 1870 and set up the new capital there on 2 July 1871, after a temporary move to Florence in 1864. The new Royal residence was the Quirinal Palace.

The rest of Victor Emmanuel II's reign was much quieter. After the Kingdom of Italy was established he decided to continue on as King Victor Emmanuel II instead of Victor Emmanuel I of Italy. This was a terrible move as far as public relations went as it was not indicative of the fresh start that the Italian people wanted and suggested that Piedmont-Sardinia had taken over the Italian Peninsula, rather than unifying it. Despite this mishap, the remainder of Victor Emmanuel II's reign was consumed by wrapping up loose ends and dealing with economic and cultural issues. His role in day-to-day governing gradually dwindled, as it became increasingly apparent that a king could no longer keep a government in office against the will of Parliament. As a result, while the wording of the Statuto Albertino stipulating that ministers were solely responsible to the crown remained unchanged, in practice they were now responsible to Parliament.

Victor Emmanuel died in Rome in 1878, after meeting with the envoys of Pope Pius IX, who had reversed the excommunication, and received last rites. He was buried in the Pantheon. His successor was his son Umberto I.[4]

Family and children

In 1842 he married his paternal first cousin (aunt's daughter) Adelaide of Austria (1822–1855). With her, he had eight children:[5]

- Maria Clotilde (1843–1911), who married Napoléon Joseph (the Prince Napoléon). Their grandson Prince Louis Napoléon was the Bonapartist pretender to the French imperial throne.

.jpg.webp)

- Umberto (1844–1900), later King of Italy. He married his first cousin Margherita of Savoy.

- Amadeo (1845–1890), later King of Spain. He married Maria Vittoria dal Pozzo and later Maria Letizia Bonaparte.

- Oddone Eugenio Maria (1846–1866), Duke of Montferrat.

- Maria Pia (1847–1911), who married King Louis of Portugal.

- Carlo Alberto (2 June 1851 – 28 June 1854), Duke of Chablais.

- Vittorio Emanuele (6 July 1852 – 6 July 1852).

- Vittorio Emanuele (18 January 1855 – 17 May 1855), Count of Geneva.

In 1869 he married morganatically his principal mistress Rosa Vercellana (3 June 1833 – 26 December 1885). Popularly known in Piedmontese as "Bela Rosin", she was born a commoner but made Countess of Mirafiori and Fontanafredda in 1858. Their offspring were:

- Vittoria Guerrieri (2 December 1848 – 29 December 1905), married three times: to Giacomo Spinola, Luigi Spinola and Paolo DeSimone. She had issue.

- Emanuele Alberto Guerrieri (16 March 1851 – 24 December 1894), Count of Mirafiori and Fontanafredda, married and had issue.

In addition to his morganatic second wife, Victor Emmanuel II had several other mistresses:

1) Laura Bon at Stupinigi, who bore him two children:

- Stillborn child (1852-1852).

- Emanuela of Roverbella (6 September 1853 – 1896).

2) Baroness Vittoria Duplesis who bore him another daughter:

- Maria Savoiarda Projetti (1854–1885/1888).

3) Unknown mistress at Mondovì, mother of:

- Donato Etna (1858–1938) who became a soldier during the First World War.

4) Virginia Rho at Turin, mother of two children:

- Vittorio di Rho (1861 – Turin, 10 October 1913). He became a notable photographer.

- Maria Pia di Rho (25 February 1866 – Vienna, 19 April 1947). Married to count Alessandro Montecuccoli.

5) Rosalinda Incoronata De Domenicis (1846–1916), mother of one daughter:

- Vittoria De Domenicis (1869–1935) who married doctor Alberto Benedetti (1870–1920), with issue.

6) Angela Rosa De Filippo, mother of:

- Actor Domenico Scarpetta (1876–1952)

Honours and arms

| Styles of King Victor Emmanuel II | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Majesty |

Italian

- Knight of the Order of the Annunciation, 23 December 1836;[6] Grand Master, 23 March 1849

- Grand Cross of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, 1836; Grand Master, 23 March 1849

- Grand Master of the Military Order of Savoy

- Grand Master of the Order of the Crown of Italy

- Grand Master of the Civil Order of Savoy

- Gold Medal of Military Valour

- Silver Medal of Military Valour

- Medal of the Liberation of Rome (1849–1870)

- Commemorative Medal of Campaigns of Independence Wars

- Commemorative Medal of the Unity of Italy

Tuscan Grand Ducal family: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Joseph[7]

Tuscan Grand Ducal family: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Joseph[7]

Foreign

Austrian Empire:

Austrian Empire:

- Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, 1841[8]

- Grand Cross of the Order of St. Stephen, 1869[9]

.svg.png.webp) Baden:[10]

Baden:[10]

- Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1864

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Zähringer Lion, 1864

.svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Bavaria: Knight of the Order of St. Hubert, 1869[11]

Kingdom of Bavaria: Knight of the Order of St. Hubert, 1869[11].svg.png.webp) Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 25 July 1855[12]

Belgium: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold, 25 July 1855[12] Denmark: Knight of the Order of the Elephant, 2 September 1861[13]

Denmark: Knight of the Order of the Elephant, 2 September 1861[13].svg.png.webp) French Empire:

French Empire:

.svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Hawaii: Grand Cross of the Order of Kamehameha I, 1865[14]

Kingdom of Hawaii: Grand Cross of the Order of Kamehameha I, 1865[14].svg.png.webp) Mexican Empire: Grand Cross of the Order of the Mexican Eagle, with Collar, 1865[15]

Mexican Empire: Grand Cross of the Order of the Mexican Eagle, with Collar, 1865[15].svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Prussia:[16]

Kingdom of Prussia:[16]

- Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle, 12 January 1866; with Collar, 1875

- Pour le Mérite (military), 29 May 1872

.svg.png.webp) Kingdom of Saxony: Knight of the Order of the Rue Crown, 1850[17]

Kingdom of Saxony: Knight of the Order of the Rue Crown, 1850[17].svg.png.webp)

Sweden-Norway: Knight of the Order of the Seraphim, 30 August 1861[18]

Sweden-Norway: Knight of the Order of the Seraphim, 30 August 1861[18].svg.png.webp) Beylik of Tunis: Husainid Family Order[19]

Beylik of Tunis: Husainid Family Order[19] United Kingdom: Stranger Knight of the Order of the Garter, 5 December 1855[20]

United Kingdom: Stranger Knight of the Order of the Garter, 5 December 1855[20]

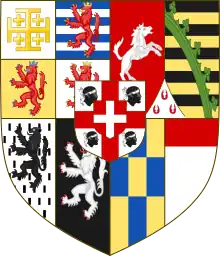

Arms

.svg.png.webp) |

.svg.png.webp) |

.svg.png.webp) |

|---|---|---|

| Arms as knight of the Golden Fleece | Coat of arms as King of Sardinia (1849–1861) | Greater coat of arms as King of Italy (1861–1878) |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Victor Emmanuel II |

|---|

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Victor Emmanuel and his successors retained the title "King of Sardinia" after the Kingdom of Sardinia became the Kingdom of Italy in 1861.

References

- ↑ Arnold, Guy (2002). Historical Dictionary of the Crimean War. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810866133.

- 1 2 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Mack Smith, Denis Italy and its Monarchy, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989 p. 42

- ↑ "Excommunicating Politicians". 27 September 2004.

- ↑ Genealogical data from the Savoia page of the Genealogie delle famiglie nobili italiane website.

- ↑ Luigi Cibrario (1869). Notizia storica del nobilissimo ordine supremo della santissima Annunziata. Sunto degli statuti, catalogo dei cavalieri. Eredi Botta. p. 107.

- ↑ Almanacco Toscano per l'anno 1855. Stamperia Granducale. 1840. p. 275.

- ↑ Boettger, T. F. "Chevaliers de la Toisón d'Or - Knights of the Golden Fleece". La Confrérie Amicale. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ↑ "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1865), "Großherzogliche Orden" pp. 55, 66

- ↑ Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Bayern (1873), "Königliche Orden" p. 8

- ↑ Ferdinand Veldekens (1858). Le livre d'or de l'ordre de Léopold et de la croix de fer. lelong. p. 214.

- ↑ Jørgen Pedersen (2009). Riddere af Elefantordenen, 1559–2009 (in Danish). Syddansk Universitetsforlag. p. 466. ISBN 978-87-7674-434-2.

- ↑ "The Royal Order of Kamehameha". crownofhawaii.com. Official website of the Royal Family of Hawaii. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ↑ "Seccion IV: Ordenes del Imperio", Almanaque imperial para el año 1866 (in Spanish), 1866, p. 242, retrieved 29 April 2020

- ↑ "Königlich Preussische Ordensliste", Preussische Ordens-Liste (in German), Berlin, 1: 12, 24, 1877

- ↑ Sachsen (1866). Staatshandbuch für den Freistaat Sachsen: 1865/66. Heinrich. p. 4.

- ↑ Sveriges statskalender (in Swedish), 1877, p. 368, retrieved 2 May 2020 – via runeberg.org

- ↑ "Nichan ad-Dam, ou ordre du Sang, institué... - Lot 198".

- ↑ Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) The Knights of England, I, London, p. 59

Sources

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Mack Smith, Denis, 1920-2017. (1972). [Victor Emanuel, Cavour and the Risorgimento.] Vittorio Emanuele II. (Traduzione ... di Jole Bertolazzi.). Laterza. OCLC 504679452.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Thayer, William Roscoe (1911). The Life and Times of Cavour vol 1. old interpretations but useful on details; vol 1 goes to 1859]; volume 2 online covers 1859–62

In Italian

- Del Boca, Lorenzo (1998). Maledetti Savoia. Casale Monferrato: Piemme.

- Gasparetto, Pier Francesco (1984). Vittorio Emanuele II. Milan: Rusconi.

- Mack Smith, Denis (1995). Vittorio Emanuele II. Milan: Mondadori.

- Pinto, Paolo (1997). Vittorio Emanuele II: il re avventuriero. Milan: Mondadori.

- Rocca, Gianni (1993). Avanti, Savoia!: miti e disfatte che fecero l'Italia, 1848–1866. Milan: Mondadori.

.jpg.webp)