_with_poles_HiRes.jpg.webp) Vastitas Borealis is the large low elevation area surrounding 70°N. | |

| Location | Northern Hemisphere, Mars |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 87°44′N 32°32′E / 87.73°N 32.53°E |

| Length | 0–360 E |

| Width | 48.25–82.08 N |

| Diameter | 2002.91 km |

| Depth | 4–5 km |

| Naming | Latin |

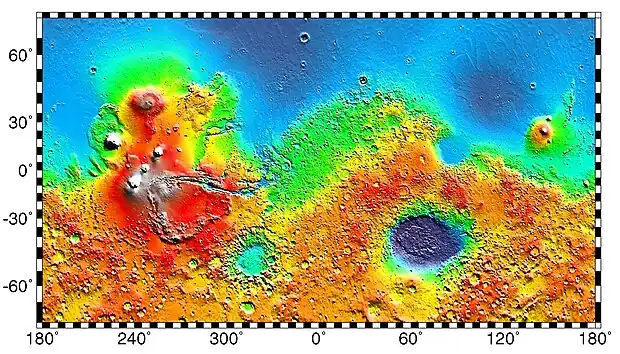

Vastitas Borealis (Latin for 'northern waste')[1] is the largest lowland region of Mars. It is in the northerly latitudes of the planet and encircles the northern polar region.[2] Vastitas Borealis is often simply referred to as the northern plains, northern lowlands or the North polar erg[3] of Mars. The plains lie 4–5 km below the mean radius of the planet, and is centered at 87°44′N 32°32′E / 87.73°N 32.53°E.[4] A small part of Vastitas Borealis lies in the Ismenius Lacus quadrangle.

The region was named by Eugene Antoniadi, who noted the distinct albedo feature of the Northern plains in his book La Planète Mars (1930). The name was officially adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1973.[5]

Although it is not an officially recognized feature, the North Polar Basin makes up most of the lowlands in the Northern Hemisphere of Mars.[6][7] As a result, Vastitas Borealis lies within the North Polar Basin, while Utopia Planitia, another very large basin, is adjacent to it. Some scientists have speculated the plains were covered by a hypothetical ocean at some point in Mars' history and putative shorelines have been suggested for its southern edges. Today these mildly sloping plains are marked by ridges, low hills, and sparse cratering. Vastitas Borealis is noticeably smoother than similar topographical areas in the south.

In 2005 the European Space Agency's Mars Express spacecraft imaged a substantial quantity of water ice in a crater in the Vastitas Borealis region. The environmental conditions at the locality of this feature are suitable for water ice to remain stable. It was revealed after overlaying frozen carbon dioxide sublimated away at the commencement of the Northern Hemisphere Summer and is believed to be stable throughout the Martian year.[8]

A NASA probe named Phoenix landed safely in a region of Vastitas Borealis unofficially named Green Valley on 25 May 2008 (in the early Martian summer). Phoenix landed at 68.218830°N 234.250778°E.[9] The probe, which will remain stationary, collected and analyzed soil samples in an effort to detect water and determine how hospitable the planet might once have been for life to grow. It remained active there until winter conditions became too harsh around five months later.[10]

Surface

Unlike some the sites visited by the Viking and Pathfinder landers, nearly all the rocks near the Phoenix landing site on Vastitas Borealis are small. For about as far as the camera can see, the land is flat, but shaped into polygons. The polygons are between 2–3 m in diameter and are bounded by troughs that are 20 to 50 cm deep. These shapes are caused by ice in the soil reacting to major temperature changes.[11] The top of the soil has a crust. The microscope showed that the soil is composed of flat particles (probably a type of clay) and rounded particles. When the soil is scooped up, it clumps together. Although other landers in other places on Mars have seen many ripples and dunes, no ripples or dunes are visible in the area of Phoenix. Ice is present a few inches below the surface in the middle of the polygons. Along the edge of the polygons the ice is at least 8 inches deep. When the ice is exposed to the Martian atmosphere it slowly disappears.[12] In the winter there would be accumulations of snow on the surface.[13]

Surface chemistry

Results published in the journal Science after the Phoenix mission ended reported that chloride, bicarbonate, magnesium, sodium, potassium, calcium, and possibly sulfate were detected in the samples. The pH was narrowed down to 7.7±0.5. Perchlorate (ClO4), a strong oxidizer, was detected. This was a significant discovery. The chemical has the potential of being used for rocket fuel and as a source of oxygen for future colonists. Under certain conditions perchlorate can inhibit life; however some microorganisms obtain energy from the substance (by anaerobic reduction). The chemical when mixed with water can greatly lower freezing points, in a manner similar to how salt is applied to roads to melt ice. Perchlorate strongly attracts water; consequently it could pull humidity from the air and produce a small amount of liquid water on Mars today.[14] Gullies, which are common in certain areas of Mars, may have formed from perchlorate melting ice and causing water to erode soil on steep slopes.[15] Two sets of experiments demonstrated that the soil contains 3–5% calcium carbonate. When a sample was slowly heated in the Thermal and Evolved-Gas Analyzer (TEGA), a peak occurred at 725 °C, which is what would happen if calcium carbonate were present. In a second experiment acid was added to a soil sample in the Wet Chemistry Laboratory (WCL) while a pH electrode measured the pH. Since the pH rose from 3.3 to 7.7, it was concluded that calcium carbonate was present. Calcium carbonate changes the texture of soil by cementing particles. Having calcium carbonate in the soil may be easier on life forms because it buffers acids, creating a pH more friendly toward life.[16]

Patterned ground

Much of the surface of Vastitas Borealis is covered with patterned ground. Sometimes the ground has the shape of polygons. Close-up views of patterned ground in the shape of polygons was provided by the Phoenix lander. In other places, the surface has low mounds arranged in chains. Some scientists first called the features fingerprint terrain because the many lines looked like someone's fingerprint.[17] Similar features in both shape and size are found in terrestrial periglacial regions such as Antarctica. Antarctica's polygons are formed by repeated expansion and contraction of the soil-ice mixture due to seasonal temperature changes. When dry soil falls into cracks sand wedges are made which increase this effect. This process results in polygonal networks of stress fractures.[18]

Patterned ground was once called fingerprint terrain because it looked like giant fingerprints. The dark dots are actually chains of low mounds. The center circular feature is a ring of dark boulders on the rim of a buried crater. Picture from Mars Global Surveyor.

Patterned ground was once called fingerprint terrain because it looked like giant fingerprints. The dark dots are actually chains of low mounds. The center circular feature is a ring of dark boulders on the rim of a buried crater. Picture from Mars Global Surveyor. Lomonosov Crater with polygonal patterned ground, as seen with Mars Global Surveyor.

Lomonosov Crater with polygonal patterned ground, as seen with Mars Global Surveyor. Korolev Crater Floor, as seen by HiRISE.

Korolev Crater Floor, as seen by HiRISE.

Defrosting

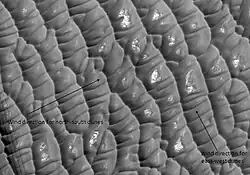

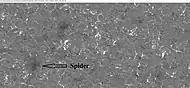

In the spring, various shapes appear because frost is disappearing from the surface, exposing the underling dark soil. Also, in some places dust is blown out of in geyser-like eruptions that are sometimes called "spiders." If a wind is blowing, the material creates a long, dark streak or fan.

Spiders and frost in polygons during northern spring, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

Spiders and frost in polygons during northern spring, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Close-up view of spider among polygons or patterned ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

Close-up view of spider among polygons or patterned ground, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Spiders shaped by the wind into streak or fans, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Polygon surface has frost in the troughs along the edges.

Spiders shaped by the wind into streak or fans, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Polygon surface has frost in the troughs along the edges. Group of dunes with most of the frost gone, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Some ripples are visible.

Group of dunes with most of the frost gone, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Some ripples are visible. Close-up of defrosting dunes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Some ripples and a small channel are also visible.

Close-up of defrosting dunes, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Some ripples and a small channel are also visible.

Glaciers

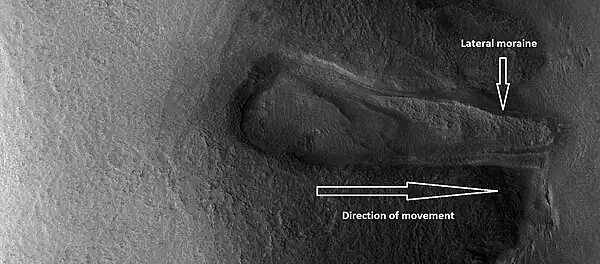

Glaciers formed much of the observable surface in large areas of Mars. Much of the area in high latitudes is believed to still contain enormous amounts of water ice.[20] In March 2010, scientists released the results of a radar study of an area called Deuteronilus Mensae that found widespread evidence of ice lying beneath a few meters of rock debris. The ice was probably deposited as snowfall during an earlier climate when the poles were tilted more.[21] Some features in Vastitas Borealis are believed to be ancient glaciers as shown in the pictures below.

Remains of a glacier after ice has disappeared, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

Remains of a glacier after ice has disappeared, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Probable glacier as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Radar studies have found that it is made up of almost completely pure ice. It appears to be moving from the high ground (a mesa) on the right.

Probable glacier as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Radar studies have found that it is made up of almost completely pure ice. It appears to be moving from the high ground (a mesa) on the right. Romer Lake's Elephant Foot Glacier in the Earth's Arctic, as seen by Landsat 8. This picture shows several glaciers that have the same shape as many features on Mars that are believed to also be glaciers.

Romer Lake's Elephant Foot Glacier in the Earth's Arctic, as seen by Landsat 8. This picture shows several glaciers that have the same shape as many features on Mars that are believed to also be glaciers.

Layers

Where the ice cap is exposed in certain places, it is found to contain many layers. Some are shown in the picture below.

Layers visible along edge of ice cap, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Layers visible along edge of ice cap, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Dunes

Dunes on floor of a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program.

Dunes on floor of a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Close-up of dunes in a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: this is an enlargement of the previous image.

Close-up of dunes in a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program. Note: this is an enlargement of the previous image. Close-up of dunes on the floor of a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Close-up of dunes on the floor of a crater, as seen by HiRISE under HiWish program

Climate

Weather

The Phoenix lander provided several months of weather observations from Mare Boreum. Wind speeds ranged from 11 to 58 km per hour. The usual average speed was 36 km per hour.[22] The highest temperature measured during the mission was −19.6 °C, while the coldest was −97.7 °C.[23] Dust devils were observed.[24]

Cirrus clouds that produced snow were sighted in Phoenix imagery. The clouds formed at a level in the atmosphere that was around −65 °C, so the clouds would have to be composed of water-ice, rather than carbon dioxide-ice because the temperature for forming carbon dioxide ice is much lower—less than −120 °C. As a result of the mission, it is now believed that water ice (snow) would have accumulated later in the year at this location.[13]

Scientists think that water ice was transported downward by snow at night. It sublimated (went directly from ice to vapor) in the morning. Throughout the day convection and turbulence mixed it back into the atmosphere.[13]

Climate cycles

Interpretation of the data transmitted from the Phoenix craft was published in the journal Science. As per the peer reviewed data the presence of water ice has been confirmed and that the site had a wetter and warmer climate in the recent past. Finding calcium carbonate in the Martian soil leads scientists to believe that the site had been wet or damp in the geological past. During seasonal or longer period diurnal cycles water may have been present as thin films. The tilt or obliquity of Mars changes far more than the Earth; hence times of higher humidity are probable.[25]

Interactive Mars map

See also

References

- ↑ Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1879. ISBN 0-19-864201-6

- ↑ "Vastitas Borealis". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Science Center. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ↑ "known as the North polar erg" Archived 30 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine at HiRISE project

- ↑ "Planetary Names: Vastitas, vastitates: Vastitas Borealis on Mars". planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ↑ USGS Planetary Nomenclature (click on the feature name for details)

- ↑ Andrews-Hanna, Jeffrey C.; Zuber, Maria T.; Banerdt, W. Bruce (1 June 2008). "The Borealis basin and the origin of the martian crustal dichotomy". Nature. 453 (7199): 1212–1215. Bibcode:2008Natur.453.1212A. doi:10.1038/nature07011. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 18580944. S2CID 1981671.

- ↑ "NASA – NASA Spacecraft Reveal Largest Crater in Solar System". nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 22 November 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ↑ "Water ice in crater at Martian north pole". European Space Agency. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- ↑ Lakdawalla, Emily (27 May 2008). "Phoenix Sol 2 press conference, in a nutshell". The Planetary Society weblog. Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014.

- ↑ "Mars lander aims for touchdown in 'Green Valley'". New Scientist Space. 11 April 2008. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012.

- ↑ Levy, J, J. Head, and D. Marchant. 2009. Thermal contraction crack polygons on Mars: Classification, distribution, and climate implications from HiRISE observations. Journal of Geographical Research: 114. p E01007

- ↑ "The Dirt on Mars Lander Soil Findings". space.com. 2 July 2009. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 Whiteway, J. et al. 2009. Mars Water-Ice Clouds and Precipitation. Science: 325. p 68–70

- ↑ "JPL". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ↑ Hecht, M. et al. 2009. Detection of Perchlorate and the Soluble Chemistry of Martian Soil at the Phoenix Lander Site. Science: 325. 64–67

- ↑ Boynton, W. et al. 2009. Evidence for Calcium Carbonate at the Mars Phoenix Landing Site. Science: 325. p 61–64

- ↑ Guest, J., P. Butterworth, and R. Greeley. 1977. Geological observations in the Cydonia region of Mars from Viking. J. Geophys. Res. 82. 4111–4120.

- ↑ Signs of Aeolian and Periglacial Activity at Vastitas Borealis (HiRISE Image ID: PSP_001481_2410) Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Murchie, S. et al. 2009. A synthesis of Martian aqueous mineralogy after 1 Mars year of observations from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Journal of Geophysical Research: 114.

- ↑ esa. "Breathtaking views of Deuteronilus Mensae on Mars". esa.int. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ↑ Madeleine, J. et al. 2007. Exploring the northern mid-latitude glaciation with a general circulation model. In: Seventh International Conference on Mars. Abstract 3096.

- ↑ "ASC – Ficher introuvable – CSA – File not found". Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ↑ "CSA – News Release". Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- ↑ Smith, P. et al. H2O at the Phoenix Landing Site. 2009. Science:325. p58-61

- ↑ Boynton, et al. 2009. Evidence for Calcium Carbonate at the Mars Phoenix Landing Site. Science. 325: 61–64

Further reading

- Martel, L.M.V. (July, 2003) Ancient Floodwaters and Seas on Mars. Planetary Science Research Discoveries. http://www.psrd.hawaii.edu/July03/MartianSea.html