Republic of Vanuatu | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Long God yumi stanap" (Bislama) Nous nous tenons devant Dieu (French) "With God we stand"[1][2] | |

| Anthem: "Yumi, Yumi, Yumi" (Bislama) "We, We, We" | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital and largest city | Port Vila 17°S 168°E / 17°S 168°E |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2020) |

|

| Religion (2020)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Ni-Vanuatu and Vanuatuan |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Nikenike Vurobaravu | |

| Charlot Salwai | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Independence | |

| 30 July 1980 | |

• Admitted to the United Nations | 15 September 1981 |

| Area | |

• Total | 12,189 km2 (4,706 sq mi) (157th) |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 335,908[4] (182nd) |

• 2020 census | 300,019[5] |

• Density | 27.6/km2 (71.5/sq mi) (188th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | $1.064 billion[6] |

• Per capita | $3,001[6] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | $1.002 billion[6] |

• Per capita | $3,188[6] |

| Gini (2010) | 37.6[7] medium |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 142nd |

| Currency | Vatu (VUV) |

| Time zone | UTC+11 (VUT (Vanuatu Time)) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +678 |

| ISO 3166 code | VU |

| Internet TLD | .vu |

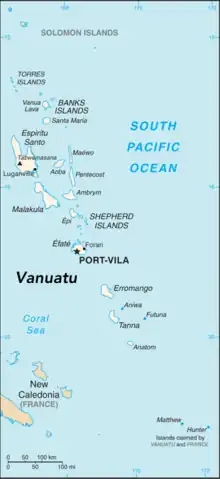

Vanuatu (English: /ˌvɑːnuˈɑːtuː/ ⓘ VAH-noo-AH-too or /vænˈwɑːtuː/ van-WAH-too; Bislama and French pronunciation [vanuatu]), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (French: République de Vanuatu; Bislama: Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country in Melanesia, located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is 1,750 km (1,090 mi) east of northern Australia, 540 km (340 mi) northeast of New Caledonia, east of New Guinea, southeast of Solomon Islands, and west of Fiji.

Vanuatu was first inhabited by Melanesian people. The first Europeans to visit the islands were a Spanish expedition led by Portuguese navigator Fernandes de Queirós, who arrived on the largest island, Espíritu Santo, in 1606. Queirós claimed the archipelago for Spain, as part of the colonial Spanish East Indies and named it La Austrialia del Espíritu Santo.

In the 1880s, France and the United Kingdom claimed parts of the archipelago, and in 1906, they agreed on a framework for jointly managing the archipelago as the New Hebrides through an Anglo-French condominium.

An independence movement arose in the 1970s, and the Republic of Vanuatu was founded in 1980. Since independence, the country has become a member of the United Nations, Commonwealth of Nations, Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, and the Pacific Islands Forum.

Etymology

Vanuatu's name derives from the word vanua ("land" or "home"),[9] which occurs in several Austronesian languages,[lower-alpha 1] combined with the word tu, meaning "to stand" (from POc *tuqur).[10] Together, the two words convey the independent status of the country.[11]

History

Prehistory

The history of Vanuatu before European colonisation is mostly obscure because of the lack of written sources up to that point, and because only limited archaeological work has been conducted; Vanuatu's volatile geology and climate is also likely to have destroyed or hidden many prehistoric sites.[12] Archaeological evidence gathered since the 1980s supports the theory that the Vanuatuan islands were first settled about 3,000 years ago, in the period roughly between 1100 BC and 700 BCE.[12][13] These were almost certainly people of the Lapita culture. The formerly widespread idea that Vanuatu might have been only marginally affected by this culture was rendered obsolete by the evidence uncovered in recent decades at numerous sites on most of the islands in the archipelago, ranging from the Banks Islands in the north to Aneityum in the south.[12]

Notable Lapita sites include Teouma on Éfaté, Uripiv, and Vao off the coast of Malakula, and Makue on Aore. Several ancient burial sites have been excavated, most notably Teouma on Éfaté, which has a large ancient cemetery containing the remains of 94 individuals.[12] There are also sites – on Éfaté and on the adjacent islands of Lelepa and Eretoka – associated with the 16th–17th century chief or chiefs called Roy Mata. (This may be a title held by different men over several generations.) Roy Mata is said to have united local clans and instituted and presided over an era of peace.[14][15]

The stories about Roy Mata come from local oral tradition and are consistent with centuries-old evidence uncovered at archaeological sites.[15] The Lapita sites became Vanuatu's first UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2008.[16][17]

The immediate origins of the Lapita lay to the northwest, in the Solomon Islands and the Bismark Archipelago of Papua New Guinea,[12] though DNA studies of a 3,000-year-old skeleton found near Port Vila in 2016 indicates that some may have arrived directly from the Philippines and/or Taiwan, pausing only briefly en route.[18] They brought with them crops such as yam, taro, and banana, as well as domesticated animals such as pigs and chickens.[12] Their arrival is coincident with the extinction of several species, such as the land crocodile (Mekosuchus kalpokasi), land tortoise (Meiolania damelipi) and various flightless bird species.[12] Lapita settlements reached as far east as Tonga and Samoa at their greatest extent.[12]

Over time, the Lapita culture lost much of its early unity; as such, it became increasingly fragmented, the precise reasons for which are unclear. Over the centuries, pottery, settlement and burial practices in Vanuatu all evolved in a more localised direction, with long-distance trade and migration patterns contracting.[12] Nevertheless, some limited long-distance trade did continue, with similar cultural practices and late-period items also being found in Fiji, New Caledonia, the Bismarks and the Solomons.[12] Finds in central and southern Vanuatu, such as distinctive adzes, also indicate some trade connections with, and possibly population movements of, Polynesian peoples to the east.[12][14]

Over time, it is thought that the Lapita either mixed with, or acted as pioneers for, migrants coming from the Bismarks and elsewhere in Melanesia, ultimately producing the darker-skinned physiognomy that is typical of modern Ni-Vanuatu.[19][20] Linguistically, the Lapita peoples' Austronesian languages were maintained, with all of the numerous 100+ autochthonous languages of Vanuatu being classified as belonging to the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian language family.[21]

This linguistic hyperdiversity resulted from a number of factors: continuing waves of migration, the existence of numerous decentralised and generally self-sufficient communities, hostilities between people groups, with none able to dominate any of the others, and the difficult geography of Vanuatu that impeded inter- and intra-island travel and communication.[22] The geological record also shows that a huge volcanic eruption occurred on Ambrym in c. 200 CE, which would have devastated local populations and likely resulted in further population movements.[12][14][23]

Arrival of Europeans (1606–1906)

The Vanuatu islands first had contact with Europeans in April 1606, when the Portuguese explorer Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, sailing for the Spanish Crown, departed El Callao,[24] sailed by the Banks Islands, landing briefly on Gaua (which he called Santa María).[14][25] Continuing further south, Queirós arrived at the largest island, naming it La Austrialia del Espíritu Santo or "The Southern Land of the Holy Spirit", believing he had arrived in Terra Australis (Australia).[12][26] The Spanish established a short-lived settlement named Nueva Jerusalem at Big Bay on the north side of the island.[14][25]

Despite Queirós's intention, relations with the Ni-Vanuatu turned violent within days. The Spanish subsequent attempts to make contact were met with the islanders fleeing or leading the explorers into an ambush.[14] Many of the crew, including Queirós, were also suffering from ill health, with Queirós's mental state also deteriorating.[14][25] The settlement was abandoned after a month, with Queirós continuing his search for the southern continent.[14]

Europeans did not return until 1768, when the French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville sailed by the islands on 22 May, naming them the Great Cyclades.[27][12] Of the various French toponyms Bougainville devised, only Pentecost Island has stuck.[25]

The French landed on Ambae, trading with the native people in a peaceful manner, though Bougainville stated that they were later attacked, necessitating him to fire warning shots with his muskets, before his crew left and continued their voyage.[25] In July–September 1774 the islands were explored extensively by British explorer Captain James Cook, who named them the New Hebrides, after the Hebrides off the west coast of Scotland, a name that lasted until independence in 1980.[28][12][25] Cook managed to maintain generally cordial relations with the Ni-Vanuatu by giving them presents and refraining from violence.[14][25]

In 1789, William Bligh and the remainder of his crew sailed through the Banks Islands on their return voyage to Timor following the mutiny on the Bounty; Bligh later returned to the islands, naming them after his benefactor Joseph Banks.[29]

Whaleships were among the first regular visitors to this group of islands. The first recorded visit was by the Rose in February 1804, and the last known visit by the New Bedford ship John and Winthrop in 1887.[30] In 1825, the trader Peter Dillon's discovery of sandalwood on the island of Erromango, highly valued as an incense in China where it could be traded for tea, resulted in rush of incomers that ended in 1830 after a clash between immigrant Polynesian workers and indigenous Ni-Vanuatu.[12][31][32][33] Further sandalwood trees were found on Efate, Espiritu Santo, and Aneityum, prompting a series of boom and busts, though supplies were essentially exhausted by the mid-1860s, and the trade largely ceased.[31][33]

During the 1860s, planters in Australia, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the Samoan islands, in need of labourers, encouraged a long-term indentured labour trade called "blackbirding".[33] At the height of the labour trade, more than one-half the adult male population of several of the islands worked abroad. Because of this, and the poor conditions and abuse often faced by workers, as well the introduction of common diseases to which native Ni-Vanuatu had no immunity, the population of Vanuatu declined severely, with the current population being greatly reduced compared to pre-contact times.[28][12][33] Greater oversight of the trade saw it gradually wind down, with Australia barring any further 'blackbird' labourers in 1906, followed by Fiji and Samoa in 1910 and 1913 respectively.[33]

From 1839 onwards, missionaries, both Roman Catholic and Protestant, arrived on the islands.[14][33] At first, they faced hostility, most notably with the killings of John Williams and James Harris of the London Missionary Society on Erromango in 1839.[14][34] Despite this they pressed on, resulting in many conversions. To the consternation of the European, this was often only skin-deep, with Ni-Vanuatu syncretising Christianity with traditional kastom beliefs.[33] The Anglican Melanesian Mission also took promising young converts for further training in New Zealand and Norfolk Island.[14] Presbyterian missionaries proved particularly successful on Aneityum, though less so on Tanna, with missionaries being repeatedly chased off the island by locals throughout the 1840s–60s.[14] The hostile response may have been partly to blame with the waves of illnesses and deaths the missionaries inadvertently brought with them.[14][33]

Other European settlers also came, looking for land for cotton plantations, the first of these being Henry Ross Lewin on Tanna in 1865 (which he later abandoned).[35] When international cotton prices collapsed after the ending of the American Civil War, they switched to coffee, cocoa, bananas, and, most successfully, coconuts. Initially British subjects from Australia made up the majority of settlers, but with little support from the British government they frequently struggled to make a success of their settlements.[33]

French planters also began arriving, beginning with Ferdinand Chevillard on Efate in 1880, and later in larger numbers following the creation of the Compagnie Caledonienne des Nouvelles-Hébrides (CCNH) I. 1882 by John Higginson (a fiercely pro-French Irishman), which soon tipped the balance in favour of French subjects.[36][37] The French government took over the CCNH in 1894 and actively encouraged French settlement.[33] By 1906, French settlers (at 401) outnumbered the British (228) almost two to one.[28][33]

Colonial era (1906–1980)

Early period (1906–1945)

The jumbling of French and British interests in the islands and the near lawlessness prevalent there brought petitions for one or another of the two powers to annex the territory.[33] The Convention of 16 October 1887 established a joint naval commission for the sole purpose of protecting French and British citizens, with no claim to jurisdiction over internal native affairs.[14][38] Hostilities between settlers and Ni-Vanuatu were commonplace, often centring on disputes over land which had been purchased in dubious circumstances.[33] There was pressure from French settlers in New Caledonia to annex the islands, though Britain was unwilling to relinquish their influence completely.[14]

As a result, in 1906 France and the United Kingdom agreed to administer the islands jointly; called the Anglo-French Condominium, it was a unique form of government, with two separate governmental, legal, judicial and financial systems that came together only in a (weak and ineffective) Joint Court.[33][39] Land expropriation and exploitation of Ni-Vanuatu workers on plantations continued apace.[33] In an effort to curb the worst of the abuses, and with the support of the missionaries, the Condominium's authority was extended via the Anglo-French Protocol of 1914, although this was not formally ratified until 1922.[33] Whilst this resulted in some improvements, labour abuses continued and Ni-Vanuatu were barred from acquiring the citizenship of either power, being officially stateless.[28][33] The underfunded Condominium government proved dysfunctional, with the duplication of administrations making effective governance difficult and time-consuming.[33] Education, healthcare and other such services were left in the hands of the missionaries.[33]

During the 1920s–1930s, indentured workers from Vietnam (then part of French Indochina) came to work in the plantations in the New Hebrides.[40] By 1929, there were some 6,000 Vietnamese people in the New Hebrides.[33][40] There was some social and political unrest among them in the 1940s due to the poor working conditions and the social effects of Allied troops, who were generally more sympathetic to their plight than the planters.[41] Most Vietnamese were repatriated in 1946 and 1963, though a small Vietnamese community remains in Vanuatu today.[42]

The Second World War brought immense change to the archipelago. The fall of France to Nazi Germany in 1940 allowed Britain to gain a greater level of authority on the islands.[39] The Australian military stationed a 2,000-strong force on Malakula in a bid to protect Australia from a possible Japanese invasion.[39] Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, the United States joined the war on the Allied side; Japan soon advanced rapidly throughout Melanesia and was in possession of much of what is now Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands by April 1942, leaving the New Hebrides on the frontline of any further advance.[39] To forestall this, from May 1942 US troops were stationed on the islands, where they built airstrips, roads, military bases and an array of other supporting infrastructure on Efate and Espiritu Santo.[43]

At the peak of the deployment, some 50,000 Americans were stationed on the two military bases, outnumbering the native population of roughly 40,000, with thousands more Allied troops passing through the islands at some point.[43] A small Ni-Vanuatu force of some 200 men (the New Hebrides Defence Force) was established to support the Americans, and thousands more were engaged in the construction and maintenance work as part of the Vanuatu Labor Corps.[43] The American presence effectively sidelined the Anglo-French authorities for the duration of their stay, with the Americans' more tolerant and friendly attitude to the Ni-Vanuatu, informal habits, relative wealth, and the presence of African American troops serving with a degree of equality (albeit in a segregated force) seriously undermining the underlying ethos of colonial superiority.[43]

Wartime Vanuatu was the setting for James Michener's novel Tales of the South Pacific.

With the successful reoccupation of the Solomons in 1943 the New Hebrides lost their strategic importance, and the Americans withdrew in 1945, selling much of their equipment at bargain prices and dumping the rest in the sea, at a place now called Million Dollar Point on Espiritu Santo.[33] The rapid American deployment and withdrawal led to growth in 'cargo cults', most notably that of John Frum, whereby Ni-Vanuatu hoped that by returning to traditional values whilst mimicking aspects of the American presence that 'cargo' (i.e. large quantities of American goods) would be delivered to them.[44][45] Meanwhile, the Condominium government returned, though understaffed and underfunded, it struggled to reassert its authority.[33]

Lead-up to independence (1945–1980)

Decolonisation began sweeping the European empires after the war, and from the 1950s the Condominium government began a somewhat belated campaign of modernisation and economic development.[33] Hospitals were built, doctors trained and immunisation campaigns carried out.[33] The inadequate mission-run school system was taken over and improved, with primary enrollment greatly increasing to be near-universal by 1970.[33] There was greater oversight of the plantations, with worker exploitation being clamped down on and Ni-Vanuatu paid higher wages.[33]

New industries, such as cattle ranching, commercial fishing and manganese mining were established.[33] Ni-Vanuatu began gradually to take over more positions of power and influence within the economy and the church.[33] Despite this, the British and French still dominated the politics of the colony, with an Advisory Council set up in 1957 containing some Ni-Vanuatu representation having little power.[33]

The economic development had unintended consequences. In the 1960s, many planters began fencing off and clearing large areas of bushland for cattle ranching, which were often deemed to be communally-held kastom lands by Ni-Vanuatu.[33] On Espiritu Santo, the Nagriamel movement was founded in 1966 by Chief Buluk and Jimmy Stevens on a platform of opposing any further land clearances and gradual, Ni-Vanuatu-led, economic development.[33][46] The movement gained a large following, prompting a crackdown by the authorities, with Buluk and Stevens being arrested in 1967.[33] Upon their release, they began to press for complete independence.[33] In 1971, Father Walter Lini established another party: the New Hebrides Cultural Association, later renamed the New Hebrides National Party (NHNP), which also focused on achieving independence and opposition to land expropriation.[33] The NNDP first came to prominence in 1971, when the Condominium government was forced to intervene after a rash of land speculation by foreign nationals.[33]

Meanwhile, French settlers, and Francophone and mixed-race Ni-Vanuatu, established two separate parties on a platform of more gradual political development – the Mouvement Autonomiste des Nouvelles-Hébrides (MANH), based on Espiritu Santo, and the Union des Communautés des Nouvelles-Hébrides (UCNH) on Efate.[33] The parties aligned on linguistic and religious lines: the NHNP was seen as the party of Anglophone Protestants, and were backed by the British who wished to exit the colony altogether, whereas the MANH, UCNH, Nagriamel and others (collectively known as the 'Moderates') represented Catholic Francophone interests, and a more gradual path to independence.[33] France backed these groups as they were keen to maintain their influence in the region, most especially in their mineral-rich colony of New Caledonia where they were attempting to suppress an independence movement.[33][47]

Meanwhile, economic development continued, with numerous banks and financial centres opening up in the early 1970s to take advantage of the territory's tax haven status.[33] A mini-building boom took off in Port Vila and, following the building of a deep-sea wharf, cruise ship tourism grew rapidly, with annual arrivals reaching 40,000 by 1977.[33] The boom encouraged increasing urbanisation and the populations of Port Vila and Luganville grew rapidly.[33]

In November 1974, the British and French met and agreed to create New Hebrides Representative Assembly in the colony, based partly on universal suffrage and partly on appointed persons representing various interest groups.[33] The first election took place in November 1975, resulting in an overall victory for the NHNP.[33] The Moderates disputed the results, with Jimmy Stevens threatening to secede and declare independence.[33] The Condominium's Resident Commissioners decided to postpone the opening of the Assembly, though the two sides proved unable to agree on a solution, prompting protests and counter-protests, some of which turned violent.[33][48][49] After discussions and some fresh elections in disputed areas, the Assembly finally convened in November 1976.[33][50][51] The NHNP renamed itself the Vanua'aku Pati (VP) in 1977, and now supported immediate independence under a strong central government and an Anglicisation of the islands. The Moderates meanwhile supported a more gradual transition to independence and a federal system, plus the maintenance of French as an official language.[33]

In March 1977, a joint Anglo-French and Ni-Vanuatu conference was held in London, at which it was agreed to hold fresh Assembly elections and later an independence referendum in 1980; the VP boycotted the conference and the subsequent election in November.[33][52] They set up a parallel 'People's Provisional Government' which had de facto control of many areas, prompting violent confrontations with Moderates and the Condominium government.[33][53][54]

A compromise was eventually brokered, a Government of National Unity formed under a new constitution, and fresh elections held in November 1979, which the VP won with a comfortable majority. Independence was now scheduled for 30 July 1980.[33] Performing less well than expected, the Moderates disputed the results.[33][55]

Tensions continued throughout 1980. Violent confrontations occurred between VP and Moderate supporters on several islands.[33] On Espiritu Santo Nagriamel and Moderate activists under Jimmy Stevens, funded by the American libertarian organisation Phoenix Foundation, took over the island's government in January and declared the independent Republic of Vemarana, prompting VP supporters to flee and the central government to institute a blockade.[33][56] In May an abortive Moderate rebellion broke out on Tanna, in the course of which one of their leaders was shot and killed.[33] The British and French sent in troops in July in a bid to forestall the Vemarana secessionists. Still ambivalent about independence, the French effectively neutered the force, prompting a collapse of law and order on Espiritu Santo resulting in large scale looting.[33]

Independence (1980–present)

The New Hebrides, now renamed Vanuatu, achieved independence as planned on 30 July 1980 under Prime Minister Walter Lini, with a ceremonial President replacing the Resident Commissioners.[33][57][58] The Anglo-French forces withdrew in August, and Lini called in troops from Papua New Guinea, sparking the brief 'Coconut War' against Jimmy Stevens's Vemarana separatists.[33][59] The PNG forces quickly quelled the Vemarana revolt and Stevens surrendered on 1 September; he was later jailed.[33][60][61] Lini remained in office until 1991, running an Anglophone-dominated government and winning both the 1983 and 1987 elections.[62][63]

In foreign affairs, Lini joined the Non Aligned Movement, opposed Apartheid in South Africa and all forms of colonialism, established links with Libya and Cuba, and opposed the French presence in New Caledonia and their nuclear testing in French Polynesia.[64][65] Opposition to Lini's tight grip on power grew and in 1987, after he had suffered a stroke whilst on a visit to the United States, a section of the Vanua'aku Pati (VP) under Barak Sopé broke off to form a new party (the Melanesian Progressive Party, MPP), and an attempt was made by President Ati George Sokomanu to unseat Lini.[59] This failed, and Lini became increasingly distrustful of his VP colleagues, firing anyone he deemed to be disloyal.[63]

One such person, Donald Kalpokas, subsequently declared himself to be VP leader, splitting the party in two.[63] On 6 September 1991 a vote of no confidence removed Lini from power;[63] Kalpokas became Prime Minister, and Lini formed a new party, the National United Party (NUP).[63][59] Meanwhile, the economy had entered a downturn, with foreign investors and foreign aid put off by Lini's flirtation with Communist states and tourist numbers down due to the political turmoil, compounded by a crash in the price of copra, Vanuatu's main export.[63] As a result, the Francophone Union of Moderate Parties (UMP) won the 1991 election, but not with enough seats to form a majority. A coalition was thus formed with Lini's NUP, with the UMP's Maxime Carlot Korman becoming Prime Minister.[63]

Since the 1991 general election, Vanuatuan politics have been unstable with a series of fractious coalition governments and the use of no confidence votes resulting in frequent changes of prime ministers. The democratic system as a whole has been maintained and Vanuatu remains a peaceful and reasonably prosperous state. Throughout most of the 1990s the UMP were in power, the prime ministership switching between UMP rivals Korman and Serge Vohor, and the UMP instituting a more free market approach to the economy, cutting the public sector, improving opportunities for Francophone Ni-Vanuatu and renewing ties with France.[63][66] The government struggled with splits in their NUP coalition partner and a series of strikes within the Civil Service in 1993–1994, the latter dealt with by a wave of firings.[63] Financial scandals dogged both Korman and Vohor, with the latter implicated in a scheme to sell Vanuatu passports to foreigners.[67][68]

In 1996, Vohor and President Jean-Marie Léyé were briefly abducted by the Vanuatu Mobile Force over a pay dispute and later released unharmed.[69][59] A riot occurred in Port Vila in 1998 when savers attempted to withdraw funds from the Vanuatu National Provident Fund following allegations of financial impropriety, prompting the government to declare a brief state of emergency.[59][68] A Comprehensive Reform Program was enacted in the 1998 with the aim of improving economic performance and cracking down on government corruption.[68] At the 1998 Vanuatuan general election the UMP were unseated by the VP under Donald Kalpokas.[59][70][71] He lasted only a year, resigning when threatened with a no confidence vote, replaced by Barak Sopé of the MPP in 1999, himself unseated in a no confidence vote in 2001.[72][68] Despite the political uncertainty Vanuatu's economy continued to grow in this period, fuelled by high demand for Vanuatu beef, tourism, remittances from foreign workers, and large aid packages from the Asian Development Bank (in 1997) and the US Millennium Challenge fund (in 2005).[73] Vanuatu was removed from the OECD list of 'uncooperative tax havens' in 2003 and joined the World Trade Organization in 2011.[73][74]

Edward Natapei of the VP became Prime Minister in 2001 and went on to win the 2002 Vanuatuan general election.[75] The 2004 Vanuatuan general election saw Vohor and the UMP return to power. He lost much support over a secret deal to recognise Taiwan in the China-Taiwan dispute and was unseated in a confidence vote less than five months after taking office, being replaced by Ham Lini.[76][77] Lini switched back recognition to the People's Republic of China and the PRC remains a major aid donor to the Vanuatu government.[78][79] In 2007 violent clashes broke out in Port Vila between migrants from Tanna and Ambrym, in which two people died.[80][74] Lini lost the 2008 Vanuatuan general election, with Natapei returning to power as Vanuatu politics entered a period of turmoil. There were frequent attempts by the opposition to unseat Natapei via the use of no confidence votes – though unsuccessful, he was briefly removed on a procedural technicality in November 2009, an action that was then overturned by the Chief Justice.[81][82] Sato Kilman of the People's Progressive Party (PPP) ousted Natapei in another no confidence vote in December 2010. He was removed in the same manner by Vohor's UMP in April 2011. This was invalidated on a technical point and he returned as PM. The Chief Justice then overturned his victory. Natapei returned to power for ten days, until Parliament voted in Kilman again.[83] Kilman managed to remain in office for two years, before being ousted in March 2013.[84]

The new government was the first time the Green Confederation was in power, and the new Prime Minister, Moana Carcasses Kalosil, was the first non-Ni-Vanuatu to hold the position (Kalosil is of mixed French-Tahitian ancestry and a naturalised Vanuatu citizen). Kalosil instituted a review of the sale of diplomatic passports and publicly declared his support for the West Papua independence movement, a move supported by former PMs Kilman and Carlot Korman.[85][86][87][88] Kalosil was ousted in yet another confidence vote in 2014, with the VP returning under Joe Natuman, who himself was ousted the following year in a confidence vote led by Kilman, angered at being fired from his position of Foreign Affairs Minister. Meanwhile, the country was devastated by Cyclone Pam in 2015, which resulted in 16 deaths and enormous destruction.[89]

A corruption investigation in 2015 resulted in the conviction of numerous MPs in Kilman's government for bribery, including former PM Moana Carcasses Kalosil.[90][91] His authority severely weakened, Kilman lost the 2016 Vanuatuan general election to Charlot Salwai's Reunification Movement for Change (RMC). Salwai in turn lost the 2020 Vanuatuan general election amidst allegations of perjury, bringing back in the VP under Bob Loughman as the country dealt with the aftermath of Cyclone Harold and the global COVID-19 pandemic.[92][93]

Vanuatu was one of the last places on Earth to suffer a coronavirus outbreak, recording its first case of COVID-19 in November 2020.[94]

In October 2023, Vanuatu aimed itself at being the first Pacific country to eliminate cervical cancer.[95]

Geography

Vanuatu is a Y-shaped archipelago consisting of about 83 relatively small, geologically newer islands of volcanic origin (65 of them inhabited), with about 1,300 kilometres (810 mi) between the most northern and southern islands.[96][97] Two of these islands (Matthew and Hunter) are also claimed and controlled by France as part of the French collectivity of New Caledonia. The country lies between latitudes 13°S and 21°S and longitudes 166°E and 171°E.

The fourteen of Vanuatu's islands that have surface areas of more than 100 square kilometres (39 sq mi) are, from largest to smallest: Espiritu Santo, Malakula, Efate, Erromango, Ambrym, Tanna, Pentecost, Epi, Ambae or Aoba, Gaua, Vanua Lava, Maewo, Malo and Aneityum or Anatom. The nation's largest towns are the capital Port Vila, on Efate, and Luganville on Espiritu Santo.[98] The highest point in Vanuatu is Mount Tabwemasana, at 1,879 metres (6,165 ft), on the island of Espiritu Santo.

Vanuatu's total area is roughly 12,274 square kilometres (4,739 sq mi),[99] of which its land surface is very limited (roughly 4,700 square kilometres (1,800 sq mi)). Most of the islands are steep, with unstable soils and little permanent fresh water.[97] One estimate, made in 2005, is that only 9% of land is used for agriculture (7% with permanent crops, plus 2% considered arable).[100] The shoreline is mostly rocky with fringing reefs and no continental shelf, dropping rapidly into the ocean depths.[97]

There are several active volcanoes in Vanuatu, including Lopevi, Mount Yasur and several underwater volcanoes. Volcanic activity is common, with an ever-present danger of a major eruption; a nearby undersea eruption of 6.4 magnitude occurred in November 2008 with no casualties, and an eruption occurred in 1945.[101] Vanuatu is recognised as a distinct terrestrial ecoregion, which is known as the Vanuatu rain forests.[102] It is part of the Australasian realm, which includes New Caledonia, the Solomon Islands, Australia, New Guinea and New Zealand.

Vanuatu's population (estimated in 2008 as growing 2.4% annually)[103] is placing increasing pressure on land and resources for agriculture, grazing, hunting, and fishing. 90% of Vanuatu households fish and consume fish, which has caused intense fishing pressure near villages and the depletion of near-shore fish species. While well-vegetated, most islands show signs of deforestation. The islands have been logged, particularly of high-value timber, subjected to wide-scale slash-and-burn agriculture, and converted to coconut plantations and cattle ranches, and now show evidence of increased soil erosion and landslides.[97]

Many upland watersheds are being deforested and degraded, and fresh water is becoming increasingly scarce. Proper waste disposal, as well as water and air pollution, are becoming troublesome issues around urban areas and large villages. Additionally, the lack of employment opportunities in industry and inaccessibility to markets have combined to lock rural families into a subsistence or self-reliance mode, putting tremendous pressure on local ecosystems.[97] The country had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.82/10, ranking it 18th globally out of 172 countries.[104]

Flora and fauna

Despite its tropical forests, Vanuatu has relatively few terrestrial plant and animal species. It has an indigenous flying fox, Pteropus anetianus. Flying foxes are important rainforest and timber regenerators. They pollinate and seed disperse a wide variety of native trees. Their diet is nectar, pollen and fruit and they are commonly called "fruit bats". They are in decline across their South Pacific range. Governments are increasingly made aware of why flying foxes' economic and ecological value should be protected. There are no indigenous large mammals.

The 19 species of native reptiles include the flowerpot snake, found only on Efate. The Fiji banded iguana (Brachylophus fasciatus) was introduced as a feral animal in the 1960s.[105][106] There are eleven species of bats (three unique to Vanuatu) and sixty-one species of land and water birds. While the small Polynesian rat is thought to be indigenous, the large species arrived with Europeans, as did domesticated hogs, dogs, and cattle. The ant species of some of the islands of Vanuatu were catalogued by E. O. Wilson.[107]

The region is rich in sea life, with more than 4,000 species of marine molluscs and a large diversity of marine fishes. Cone snails and stonefish carry poison fatal to humans. The Giant East African land snail arrived only in the 1970s, but already has spread from the Port Vila region to Luganville.

There are three or possibly four adult saltwater crocodiles living in Vanuatu's mangroves and no current breeding population.[106] It is said the crocodiles reached the northern part of the islands after cyclones, given the island chain's proximity to the Solomon Islands and New Guinea where crocodiles are very common.[108]

Climate

The climate is tropical, with about nine months of warm to hot rainy weather and the possibility of cyclones and three to four months of cooler, drier weather characterised by winds from the southeast. The water temperature ranges from 22 °C (72 °F) in winter to 28 °C (82 °F) in the summer. Cool between April and September, the days become hotter and more humid starting in October. The daily temperature ranges from 20–32 °C (68–90 °F). Southeasterly trade winds occur from May to October.[97]

Vanuatu has a long rainy season, with significant rainfall almost every month. The wettest and hottest months are December through April, which also constitutes the cyclone season. The driest months are June through November.[97] Rainfall averages about 2,360 millimetres (93 in) per year but can be as high as 4,000 millimetres (160 in) in the northern islands.[100] According to the WorldRiskIndex 2021, Vanuatu ranks first among the countries with the highest disaster risk worldwide.[109]

In 2023, the governments of Vanuatu and other vulnerable to climate change islands (Fiji, Niue, the Solomon Islands, Tonga and Tuvalu) launched the "Port Vila Call for a Just Transition to a Fossil Fuel Free Pacific", calling for the phase out fossil fuels and the 'rapid and just transition' to renewable energy and strengthening environmental law including introducing the crime of ecocide.[110][111][112]

Tropical cyclones

.jpg.webp)

In March 2015, Cyclone Pam impacted much of Vanuatu as a Category 5 severe tropical cyclone, causing deaths and extensive damage to all the islands. As of 17 March 2015 the United Nations said the official death toll was 11 (six from Efate and five from Tanna), and 30 were reported injured; these numbers were expected to rise as more remote islands reported back.[113][114] Vanuatu lands minister, Ralph Regenvanu said, "This is the worst disaster to affect Vanuatu ever as far as we know."[115]

In April 2020, Cyclone Harold travelled through the Espiritu Santo town of Luganville, causing great material damage there and on at least four islands.[116]

Earthquakes

Vanuatu has relatively frequent earthquakes. Of the 58 M7 or greater events that occurred between 1909 and 2001, few were studied.

Government

Politics

The Republic of Vanuatu is a parliamentary democracy[117] with a written constitution, which declares that the "head of the Republic shall be known as the President and shall symbolise the unity of the nation." The powers of the President of Vanuatu, who is elected for a five-year term by a two-thirds vote of an electoral college, are primarily ceremonial.[118] The electoral college consists of members of Parliament and the presidents of Regional Councils. The President may be removed by the electoral college for gross misconduct or incapacity.

The Prime Minister, who is the head of government, is elected by a majority vote of a three-quarters quorum of the Parliament. The Prime Minister, in turn, appoints the Council of Ministers, whose number may not exceed a quarter of the number of parliamentary representatives. The Prime Minister and the Council of Ministers constitute the executive government.

The Parliament of Vanuatu is unicameral and has 52 members,[119] who are elected by popular vote every four years unless earlier dissolved by a majority vote of a three-quarters quorum or by a directive from the President on the advice of the Prime Minister. Forty-four of these MPs are elected through Single non-transferable voting; eight are elected through single-member plurality.

The national Council of Chiefs, called the Malvatu Mauri and elected by district councils of chiefs, advises the government on all matters concerning ni-Vanuatu culture and language.

Besides national authorities and figures, Vanuatu also has high-placed people at the village level. Chiefs continue to be the leading figures at the village level. It has been reported that even politicians need to oblige them.[120] One becomes such a figure by holding a number of lavish feasts (each feast allowing them a higher ceremonial grade) or alternatively through inheritance (the latter only in Polynesian-influenced villages). In northern Vanuatu, feasts are graded through the nimangki system.

Government and society in Vanuatu tend to divide along linguistic French and English lines. Forming coalition governments has proved problematic at times, owing to differences between English and French speakers. Francophone politicians like those of the Union of Moderate Parties tend to be conservative and support neo-liberal policies, as well as closer relations with France and the West. The anglophone Vanua'aku Pati identifies as socialist and anti-colonial.

The Supreme Court consists of a chief justice and up to three other judges. Two or more members of this court may constitute a Court of Appeal. Magistrate courts handle most routine legal matters. The legal system is based on British common law and French civil law. The constitution also provides for the establishment of village or island courts presided over by chiefs to deal with questions of customary law. Squatting occurs and the principle of adverse possession does not exist.[121]

Foreign relations

.jpg.webp)

Vanuatu has joined the Asian Development Bank, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the Agence de Coopération Culturelle et Technique, la Francophonie and the Commonwealth of Nations.

Since 1980, Australia, the United Kingdom, France and New Zealand have provided the bulk of Vanuatu's development aid. Direct aid from the UK to Vanuatu ceased in 2005 following the decision by the UK to no longer focus on the Pacific.

More recently, new donors such as the Millennium Challenge Account (MCA) of the United States and the People's Republic of China have been providing increased amounts of aid funding and loans. In 2005 the MCA announced that Vanuatu was one of the first 15 countries in the world selected to receive support – an amount of US$65 million was given for the provision and upgrading of key pieces of public infrastructure.

_(Imagicity_548).jpg.webp)

In March 2017, at the 34th regular session of the UN Human Rights Council, Vanuatu made a joint statement on behalf of some other Pacific nations raising human rights abuses in the Western New Guinea or West Papua region, which has been part of Indonesia since 1963,[122] and requested that the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights produce a report[123][124] as more than 100,000 Papuans allegedly have died during decades of Papua conflict.[125] Indonesia rejected Vanuatu's allegations.[124] In September 2017, at the 72nd Session of the UN General Assembly, the Prime Ministers of Vanuatu, Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands once again raised human rights concerns in West Papua.[126]

In 2018, newspaper reports from Australia indicated growing concern about the level of Chinese investment in Vanuatu, with over 50% of the country's debt of $440 million owed to China.[127] Concern was focused on the possibility that China would use Vanuatu's potential inability to repay debt as leverage to bargain for control of, or a People's Liberation Army presence at, Luganville Wharf. China loaned and funded the $114 million redevelopment of the wharf, which has already been constructed, with the capacity to dock naval vessels.[128]

Vanuatu retains strong economic and cultural ties to Australia, the European Union (in particular France), the UK and New Zealand. Australia now provides the bulk of external assistance, including to the police force, which has a paramilitary wing.[129]

Karen Bell is the new British High Commissioner to Vanuatu. The British High Commission to Vanuatu, located in Port Vila, was re-opened in the summer of 2019 as part of the UK Government's 'Pacific Uplift' strategy.[130] The British Friends of Vanuatu,[131] based in London, provides support for Vanuatu visitors to the UK, and can often offer advice and contacts to persons seeking information about Vanuatu or wishing to visit, and welcomes new members (not necessarily resident in the UK) interested in Vanuatu. The association's Charitable Trust funds small scale assistance in the education and training sector.

Armed forces

There are two police wings: the Vanuatu Police Force (VPF) and the paramilitary wing, the Vanuatu Mobile Force (VMF).[132] Altogether there were 547 police officers organised into two main police commands: one in Port Vila and one in Luganville.[132] In addition to the two command stations there were four secondary police stations and eight police posts. This means that there are many islands with no police presence, and many parts of islands where getting to a police post can take several days.[133][134] There is no purely military expenditure.[135] In 2017, Vanuatu signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[136][137]

Administrative divisions

Vanuatu has been divided into six provinces since 1994.[138][139] The names in English of all provinces are derived from the initial letters of their constituent islands:

- Malampa (Malakula, Ambrym, Paama)

- Penama (Pentecost, Ambae, Maewo – in French: Pénama)

- Sanma (Santo, Malo)

- Shefa (Shepherds group, Efate – in French: Shéfa)

- Tafea (Tanna, Aniwa, Futuna, Erromango, Aneityum – in French: Taféa)

- Torba (Torres Islands, Banks Islands)

Provinces are autonomous units with their own popularly elected local parliaments known officially as provincial councils.[140]

The provinces are in turn divided into municipalities (usually consisting of an individual island) headed by a council and a mayor elected from among the members of the council.[141]

Economy

The four mainstays of the economy are agriculture, tourism, offshore financial services, and raising cattle.

There is substantial fishing activity, although this industry does not bring in much foreign exchange. Exports include copra, kava, beef, cocoa and timber; imports include machinery and equipment, foodstuffs, and fuels. In contrast, mining activity is very low.

Although manganese mining halted in 1978, there was an agreement in 2006 to export manganese already mined but not yet exported. The country has no known petroleum deposits. A small light-industry sector caters to the local market. Tax revenues come mainly from import duties and a 15% VAT on goods and services. Economic development is hindered by dependence on relatively few commodity exports, vulnerability to natural disasters, and long distances between constituent islands and from main markets.

Agriculture is used for consumption as well as for export. It provides a living for 65% of the population. In particular, production of copra and kava create substantial revenue. Many farmers have been abandoning cultivation of food crops and use earnings from kava cultivation to buy food.[120] Kava has also been used in ceremonial exchanges between clans and villages.[142] Cocoa is also grown for foreign exchange.[143]

In 2007, the number of households engaged in fishing was 15,758, mainly for consumption (99%), and the average number of fishing trips was 3 per week.[144] The tropical climate enables growing of a wide range of fruits and vegetables and spices, including banana, garlic, cabbage, peanuts, pineapples, sugarcane, taro, yams, watermelons, leaf spices, carrots, radishes, eggplants, vanilla (both green and cured), pepper, cucumber and many others.[145] In 2007, the value (in terms of millions of vatu – the official currency of Vanuatu), for agricultural products, was estimated for different products: kava (341 million vatu), copra (195), cattle (135), crop gardens (93), cocoa (59), forestry (56), fishing (24) and coffee (12).[146]

In 2018, Vanuatu banned all use of plastic bags and plastic straws, with more plastic items scheduled to be banned in 2020.[147]

Tourism brings in much-needed foreign exchange. Vanuatu is widely recognised as one of the premier vacation destinations for scuba divers wishing to explore coral reefs of the South Pacific region.[148] A further significant attraction to scuba divers is the wreck of the US ocean liner and converted troop carrier SS President Coolidge on Espiritu Santo island. Sunk during World War II, it is one of the largest shipwrecks in the world that is accessible for recreational diving. Tourism increased 17% from 2007 to 2008 to reach 196,134 arrivals, according to one estimate.[149] The 2008 total is a sharp increase from 2000, in which there were only 57,000 visitors (of these, 37,000 were from Australia, 8,000 from New Zealand, 6,000 from New Caledonia, 3,000 from Europe, 1,000 from North America, 1,000 from Japan.[150] Tourism has been promoted, in part, by Vanuatu being the site of several reality-TV shows. The ninth season of the reality TV series Survivor was filmed on Vanuatu, entitled Survivor: Vanuatu—Islands of Fire. Two years later, Australia's Celebrity Survivor was filmed at the same location used by the US version. In mid-2002, the government stepped up efforts to boost tourism.

Financial services are an important part of the economy. Vanuatu is a tax haven that until 2008 did not release account information to other governments or law-enforcement agencies. International pressure, mainly from Australia, influenced the Vanuatu government to begin adhering to international norms to improve transparency. In Vanuatu, there is no income tax, withholding tax, capital gains tax, inheritance tax, or exchange control. Many international ship-management companies choose to flag their ships under the Vanuatu flag, because of the tax benefits and favourable labour laws (Vanuatu is a full member of the International Maritime Organization and applies its international conventions). Vanuatu is recognised as a "flag of convenience" country.[151] Several file-sharing groups, such as the providers of the KaZaA network of Sharman Networks and the developers of WinMX, have chosen to incorporate in Vanuatu to avoid regulation and legal challenges. In response to foreign concerns the government has promised to tighten regulation of its offshore financial centre. Vanuatu receives foreign aid mainly from Australia and New Zealand.

Vanuatu became the 185th member of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in December 2011.[152]

Raising cattle leads to beef production for export. One estimate in 2007 for the total value of cattle heads sold was 135 million vatu; cattle were first introduced into the area from Australia by British planter James Paddon.[153] On average, each household has 5 pigs and 16 chickens, and while cattle are the "most important livestock", pigs and chickens are important for subsistence agriculture as well as playing a significant role in ceremonies and customs (especially pigs).[154] There are 30 commercial farms (sole proprietorships (37%), partnerships (23%), corporations (17%)), with revenues of 533 million vatu and expenses of 329 million vatu in 2007.[155]

Earthquakes can negatively affect economic activity on the island nation. A severe earthquake in November 1999, followed by a tsunami, caused extensive damage to the northern island of Pentecost, leaving thousands homeless. Another powerful earthquake in January 2002 caused extensive damage in the capital, Port Vila, and surrounding areas, and was also followed by a tsunami. Another earthquake of 7.2 struck on 2 August 2007.[156]

The Vanuatu National Statistics Office (VNSO) released their 2007 agricultural census in 2008. According to the study, agricultural exports make up about three-quarters (73%) of all exports; 80% of the population lives in rural areas where "agriculture is the main source of their livelihood"; and of these households, almost all (99%) engaged in agriculture, fisheries and forestry.[157] Total annual household income was 1,803 million vatu. Of this income, agriculture grown for their own household use was valued at 683 million vatu, agriculture for sale at 561, gifts received at 38, handicrafts at 33 and fisheries (for sale) at 18.[157]

The largest expenditure by households was food (300 million vatu), followed by household appliances and other necessities (79 million vatu), transportation (59), education and services (56), housing (50), alcohol and tobacco (39), clothing and footwear (17).[158] Exports were valued at 3,038 million vatu, and included copra (485), kava (442), cocoa (221), beef (fresh and chilled) (180), timber (80) and fish (live fish, aquarium, shell, button) (28).[159] Total imports of 20,472 million vatu included industrial materials (4,261), food and drink (3,984), machinery (3,087), consumer goods (2,767), transport equipment (2,125), fuels and lubricants (187) and other imports (4,060).[160] There are substantial numbers of crop gardens – 97,888 in 2007 – many on flat land (62%), slightly hilly slope (31%), and even on steep slopes (7%); there were 33,570 households with at least one crop garden, and of these, 10,788 households sold some of these crops over a twelve-month period.[161]

The economy grew about 6% in the early 2000s.[162] This is higher than in the 1990s, when GDP rose less than 3%, on average.

One report from the Manila-based Asian Development Bank about Vanuatu's economy gave mixed reviews. It noted the economy was "expanding", noting that the economy grew at an impressive 5.9% rate from 2003 to 2007, and lauded "positive signals regarding reform initiatives from the government in some areas" but described certain binding constraints such as "poor infrastructure services". Since a private monopoly generates power, "electricity costs are among the highest in the Pacific" among developing countries. The report also cited "weak governance and intrusive interventions by the State" that reduced productivity.[162]

Vanuatu was ranked the 173rd safest investment destination in the world in the March 2011 Euromoney Country Risk rankings.[163] In 2015, Vanuatu was ranked the 84th most economically free country by The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal.[164]

Vanuatu sells citizenship for about $150,000, and its passports allow visa-free travel throughout Europe. With demand from the Chinese market booming, passport sales may now account for more than 30% of the country's revenue.[165] Such schemes have been shown to raise ethical problems,[166] and have been involved in some political scandals.[67][167] On 19 July 2023, Vanuatu lost UK visa-free access due to concerns over its citizenship by investment scheme.[168]

Communications

Mobile phone service in the islands is provided by Vodafone (formerly TVL)[169] and Digicel. Internet access is provided by Vodafone, Telsat Broadband, Digicel and Wantok using a variety of connection technologies. A submarine optical fibre cable now connects Vanuatu to Fiji.[170]

Demographics

According to the 2009 census, Vanuatu has a population of 243,304.[171] Men outnumber women, with the population consisting of 119,091 men and 114,932 women in 2009.[172] The population is predominantly rural, but Port Vila and Luganville have populations in the tens of thousands.

The inhabitants of Vanuatu are called ni-Vanuatu in English, using a recent coinage. The ni-Vanuatu are primarily (98.5%) of Melanesian descent, with the remainder made up of a mix of Europeans, Asians and other Pacific islanders. Three islands were historically colonised by Polynesians. About 20,000 ni-Vanuatu live and work in New Zealand and Australia.

Most Asians in Vanuatu are of Vietnamese descent, forming the community of Vietnamese in Vanuatu. Although the Vietnamese community has declined from 10% of Vanuatu's population in 1929 to about 0.3% (or 1,000 individuals) today, the Vietnamese community remains very significant and influential.[173]

In 2006, the New Economics Foundation and Friends of the Earth environmentalist group published the Happy Planet Index, which analysed data on levels of reported happiness, life expectancy and Ecological Footprint, and they estimated Vanuatu to be the most ecologically efficient country in the world in achieving high well-being.[174]

Trade in citizenship for investment has been an increasingly significant revenue earner for Vanuatu in recent years. The sale of what is called "honorary citizenship" in Vanuatu has been on offer for several years under the Capital Investment Immigration Plan and more recently the Development Support Plan. People from mainland China make up the bulk of those who have purchased honorary citizenship, entitling them to a Vanuatu passport.[166]

Languages

The national language of the Republic of Vanuatu is Bislama. The official languages are Bislama, English and French. The principal languages of education are English and French. The use of English or French as the formal language is split along political lines.[175]

Bislama is a creole spoken natively in urban areas. Combining a typical Melanesian grammar and phonology with an almost entirely English-derived vocabulary, Bislama is the lingua franca of the archipelago, used by the majority of the population as a second language.

In addition, 113 indigenous languages, all of which are Southern Oceanic languages except for three outlier Polynesian languages, are spoken in Vanuatu.[176] The density of languages, per capita, is the highest of any nation in the world,[177] with an average of only 2,000 speakers per language. All vernacular languages of Vanuatu (i.e., excluding Bislama) belong to the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian family.

In recent years, the use of Bislama as a first language has considerably encroached on indigenous languages, whose use in the population has receded from 73.1 to 63.2 percent between 1999 and 2009.[178]

Religion

Christianity is the predominant religion in Vanuatu, consisting of several denominations. About one-third of the population belongs to the Presbyterian Church in Vanuatu,[179] Roman Catholic and Anglican are other common denominations, each claiming about 15% of the population. According to its 2022 facts and statistics, 3.6% of the population belongs to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, with a countrywide membership of over 11,000.[180] As of 2010, 1.4% of the people of Vanuatu are members of the Bahá'í Faith, making Vanuatu the 6th most Bahá'í country in the world.[181] The less significant groups are the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Church of Christ,[182] Neil Thomas Ministries (NTM), Jehovah's Witnesses, and others. In 2007, Islam in Vanuatu was estimated to consist of about 200 converts.[183][184]

Because of the modern goods that the military in the Second World War brought with them when they came to the islands, several cargo cults developed. Many died out, but the John Frum cult on Tanna is still large, and has adherents in the parliament.[185] Also on Tanna is the Prince Philip Movement, which reveres the United Kingdom's Prince Philip.[186] Villagers of the Yaohnanen tribe believed in an ancient story about the pale-skinned son of a mountain spirit venturing across the seas to look for a powerful woman to marry. Prince Philip, having visited the island with his new wife Queen Elizabeth II, fit the description exactly and is therefore revered as a god around the isle of Tanna.[187] After Philip died, an anthropologist familiar with the group, said that after their period of mourning the group would probably transfer their veneration to King Charles III, who had visited Vanuatu in 2018 and met with some of the tribal leaders.[188]

Health

Education

The estimated literacy rate of people aged 15–24 years is about 74% according to UNESCO figures.[189] The rate of primary school enrolment rose from 74.5% in 1989 to 78.2% in 1999 and then to 93.0% in 2004 but then fell to 85.4% in 2007. The proportion of pupils completing a primary education fell from 90% in 1991 to 72% in 2004[190] and up to 78% in 2012.

Port Vila and three other centres have campuses of the University of the South Pacific, an educational institution co-owned by twelve Pacific countries. The campus in Port Vila, known as the Emalus Campus, houses the university's law school.

Culture

Vanuatu culture retains a strong diversity through local regional variations and through foreign influence. Vanuatu may be divided into three major cultural regions. In the north, wealth is established by how much one can give away, through a grade-taking system. Pigs, particularly those with rounded tusks, are considered a symbol of wealth throughout Vanuatu. In the centre, more traditional Melanesian cultural systems dominate. In the south, a system involving grants of title with associated privileges has developed.[176]

Young men undergo various coming-of-age ceremonies and rituals[191] to initiate them into manhood, usually including circumcision.

Most villages have a nakamal or village clubhouse, which serves as a meeting point for men and a place to drink kava. Villages also have male- and female-only sections. These sections are situated all over the villages; in nakamals, special spaces are provided for females when they are in their menstruation period.

There are few prominent ni-Vanuatu authors. Women's rights activist Grace Mera Molisa, who died in 2002, achieved international notability as a descriptive poet.

Music

The traditional music of Vanuatu is still thriving in the rural areas of Vanuatu.[192] Musical instruments consist mostly of idiophones: drums of various shape and size, slit gongs, stamping tubes, as well as rattles, among others. Another musical genre that has become widely popular during the 20th century in all areas of Vanuatu, is known as string band music. It combines guitars, ukulele, and popular songs.

More recently the music of Vanuatu, as an industry, grew rapidly in the 1990s and several bands have forged a distinctive ni-Vanuatu identity.[193] Popular genres of modern commercial music, which are currently being played in the urban areas include zouk music and reggaeton. Reggaeton, a variation of Dancehall Reggae spoken in the Spanish language, played alongside its own distinctive beat, is especially played in the local nightclubs of Port Vila with, mostly, an audience of Westerners and tourists.

Cuisine

The cuisine of Vanuatu (aelan kakae) incorporates fish, root vegetables such as taro and yams, fruits, and vegetables. Most island families grow food in their gardens, and food shortages are rare. Papayas, pineapples, mangoes, plantains, and sweet potatoes are abundant through much of the year. Coconut milk and coconut cream are used to flavour many dishes. Most food is cooked using hot stones or through boiling and steaming; very little food is fried.[97]

Sports

The most practised sport in Vanuatu is football. The top flight league is the VFF National Super League while the Port Vila Football League is another important competition.

Festivals

The island of Pentecost is known for its tradition of land diving, locally known as gol. The ritual consists of men land diving off a 98-foot-high wooden tower with their ankles tied to vines, as part of the annual yam harvest festival.[195][196] This local tradition is often credited to the inspiration of the modern practice of bungee jumping, which was developed in New Zealand in the 1980s.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Vanua in turns comes from the Proto-Austronesian *banua – see Reuter 2002, p. 29; and Reuter 2006, p. 326

References

- ↑ Selmen, Harrison (17 July 2011). "Santo chiefs concerned over slow pace of development in Sanma". Vanuatu Daily Post. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ↑ Lynch & Pat 1996, p. 319.

- ↑ "National Profiles – Religious demographics (Vanuatu)". The Association of Religion Data Archives. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ↑ "Vanuatu Population (2023) – Worldometer". worldometers.info. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ↑ "2020 National Population and Housing Census – Basic Tables Report, Volume 1, Version 2" (PDF). vnso.gov.vu. Vanuatu National Statistics Office. 17 November 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2023". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ↑ "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". World Bank. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ↑ Hess 2009, p. 115.

- ↑ See Entry *tuqu Archived 24 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine in the Polynesian Lexicon Project.

- ↑ Crowley 2004, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Spriggs, Matthew; Bedford, Stuart. "The Archaeology of Vanuatu: 3,000 Years of History across Islands of Ash and Coral". Oxford Handbooks Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ↑ Bedford & Spriggs 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Flexner, James; Spriggs, Matthew; Bedford, Stuart. "Beginning Historical Archaeology in Vanuatu: Recent Projects on the Archaeology of Spanish, French, and Anglophone Colonialism". Research Gate. Springer. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- 1 2 Chief Roi Mata's Domain – Challenges facing a World Heritage-nominated property in Vanuatu. ICOMOS. S2CID 55627858.

- ↑ "Chief Roi Mata's Domain" Archived 26 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, UNESCO

- ↑ "World Heritage Status set to ensure protection of Vanuatu's Roi Mata domain". Radio New Zealand International. 9 July 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ↑ "Origins of Vanuatu and Tonga's first people revealed". Australian National University. 4 October 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ↑ "Study of ancient skulls from Vanuatu cemetery sheds light on Polynesian migration, scientists say". ABC Radio Canberra. 29 December 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ↑ "Scientists Reveal the Genetic Timeline of Ancient Vanuatu People". SciTech Daily. 9 March 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ↑ "Languages of Vanuatu" – 2013 archive from Ethnologue.

- ↑ "The exceptional linguistic diversity of Vanuatu". Sorosoro. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ↑ Gao, Chaochao; Robock, Alan; Self, Stephen; Witter, Jeffrey B.; J. P. Steffenson; Henrik Brink Clausen; Marie-Louise Siggaard-Andersen; Sigfus Johnsen; Paul A. Mayewski; Caspar Ammann (2006). "The 1452 or 1453 A.D. Kuwae eruption signal derived from multiple ice core records: Greatest volcanic sulfate event of the past 700 years" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 111 (D12107): 11. Bibcode:2006JGRD..11112107G. doi:10.1029/2005JD006710.

- ↑ Rogers Kotlowski, Elizabeth. "Southland of the Holy Spirit". CHR. Archived from the original on 24 December 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

In 1605 [...] Quiros sailed west from Callao, Peru

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jolly, Margaret. "The Sediment of Voyages: Re-membering Quirós, Bougainville and Cook in Vanuatu". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.533.9909.

- ↑ Vanuatu and New Caledonia. Lonely Planet. 2009. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-74104-792-9. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Salmond, Anne (2010). Aphrodite's Island. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-520-26114-3.

- 1 2 3 4 "Background Note: Vanuatu". US Department of State. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ↑ Wahlroos, Sven. "Mutiny and Romance in the South Seas: A Companion to the Bounty Adventure". Pitcairn Islands Study Centre. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ↑ Langdon, Robert (1984). Where the whalers went; an index to the Pacific ports and islands visited by American whalers (and some other ships) in the 19th century. Canberra: Pacific Manuscripts Bureau. pp. 190–191. ISBN 0-86784-471-X.

- 1 2 Bule, Leonard; Daruhi, Godfrey. "Status of Sandalwood Resources in Vanuatu" (PDF). US Forest Service. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ↑ Van Trease 1987, p. 12-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 MacClancy, Jeremy (January 1981). "To Kill a Bird with Two Stones – A Short History of Vanuatu". Academia.edu. Vanuatu Cultural Centre Publications. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ↑ Van Trease 1987, p. 15.

- ↑ Van Trease 1987, p. 19.

- ↑ Vanuatu Country Study Guide. International Business Publications. 30 March 2009. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-4387-5649-3. Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- ↑ Van Trease 1987, p. 26-7.

- ↑ Bresnihan, Brian J.; Woodward, Keith (2002). Tufala Gavman: Reminiscences from the Anglo-French Condominium of the New Hebrides. editorips@usp.ac.fj. p. 423. ISBN 978-982-02-0342-6. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "A Short History Of Vanuatu". South Pacific WWII Museum. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- 1 2 Calnitsky, Naomi Alisa. "The Tonkinese Labour Traffic to the Colonial New Hebrides: The Role of French Inter-Colonial Webs". Academia.edu. Indian Ocean World Centre, McGill University. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ↑ Robequain, Charles (1950). "Les Nouvelles-Hébrides et l'immigration annamite". Annales de Géographie (in French). 59 (317): 391–392. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018.

- ↑ Buckley, Joe (8 October 2017). "In My Words Vietnamese surprises in Vanuatu". VN Express. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Lindstrom, Lamont. "The Vanuatu Labor Corps Experience" (PDF). Scholar Space. University of Hawaii. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ↑ Guiart, Jean (March 1952). "John Frum Movement in Tanna" (PDF). Oceania. 22 (3): 165–177. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4461.1952.tb00558.x. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ↑ "Western Oceanian Religions: Jon Frum Movement". University of Cumbria. Archived from the original on 16 October 2003.

- ↑ ""Chief President Moses": Man with a message for 10,000 New Hebrideans". Pacific Islands Monthly. July 1969. pp. 23–25. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "Bombs, bribery and ballots in New Hebrides". Pacific Islands Monthly. January 1976. p. 8. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "The Ghost Assembly". Pacific Islands Monthly. June 1976. p. 10. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "Splinters flying in N. Hebrides". Pacific Islands Monthly. May 1976. p. 11. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "New Hebrides Assembly meets". Pacific Islands Monthly. August 1976. p. 18. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "New Hebrides Assembly meets – but what's new?". Pacific Islands Monthly. February 1977. pp. 17–18. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "New Hebrides' new era". Pacific Islands Monthly. March 1978. p. 28. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- ↑ Van Trease, Howard (9 August 2006). "The Operation of the single non-transferable vote system in Vanuatu". Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 43 (3): 296–332. doi:10.1080/14662040500304833. S2CID 153565206.

- ↑ "Turmoil in New Hebrides". Pacific Islands Monthly. January 1978. p. 5. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "New Hebrides: High hopes haunted by high danger". Pacific Islands Monthly. January 1980. pp. 13–14. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020.

- ↑ Parsons, Mike (July 1981). "Phoenix: ashes to ashes". New Internationalist. Archived from the original on 11 May 2010.

- ↑ Shears 1980.

- ↑ "Independence". Vanuatu.travel – Vanuatu Islands. 17 September 2009. Archived from the original on 18 April 2011. Retrieved 17 September 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Vanuatu (1980–present)". University of Central Arkansas.

- ↑ "New Hebrides Rebel Urges Peace; Willing to Fight British and French One British Officer Injured". The New York Times. 9 June 1980. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- ↑ Bain, Kenneth (4 March 1994). "Obituary: Jimmy Stevens". The Independent. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ Miles, William F. S. (1998). Bridging Mental Boundaries in a Postcolonial Microcosm: Identity and Development in Vanuatu. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-8248-2048-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Steeves, Jeffrey; Premdas, Ralph (1995). "Politics in Vanuatu: the 1991 Elections". Journal de la Société des Océanistes. 100 (1): 221–234. doi:10.3406/jso.1995.1965. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ↑ Zinn, Christopher (25 February 1999). "Walter Lini obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ Huffer, Elise (1993). Grands hommes et petites îles: La politique extérieure de Fidji, de Tonga et du Vanuatu. Paris: Orstom. pp. 272–282. ISBN 2-7099-1125-6.

- ↑ Miles, William F. S. (1998). Bridging Mental Boundaries in a Postcolonial Microcosm: Identity and Development in Vanuatu. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 25–7. ISBN 0-8248-2048-7.

- 1 2 Hill, Edward R. (3 December 1997), "Public Report on Resort Las Vegas and granting of illegal passports", Digested Reports of the Vanuatu Office of the Ombudsman, vol. 97, no. 15, archived from the original on 31 March 2011, retrieved 23 May 2022

- 1 2 3 4 "Freedom in the World 1999 – Vanuatu". Freedom House. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ↑ Miles, William F. S. (1998). Bridging Mental Boundaries in a Postcolonial Microcosm: Identity and Development in Vanuatu. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-8248-2048-7.

- ↑ Miles, William F. S. (1998). Bridging Mental Boundaries in a Postcolonial Microcosm: Identity and Development in Vanuatu. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-8248-2048-7.

- ↑ Nohlen, Dieter; Grotz, Florian; Hartmann, Christof (2001). Elections in Asia: A data handbook, Volume II. p. 843. ISBN 0-19-924959-8.

- ↑ "The 5th Prime Minister". The Daily Post. 30 July 2020. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- 1 2 "History in Vanuatu". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- 1 2 "Vanuatu – timeline". BBC. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- ↑ "Vanuatu: Elections held in 2002". Inter-Parliamentary Union. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011.

- ↑ "Vanuatu court rules in favor of Parliament; Vohor appeals". Taiwan News (news.vu). 8 December 2004. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006.

- ↑ "Vanuatu tosses out the Vohor Government". Radio New Zealand International. 10 December 2004. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ↑ Wroe, David (9 April 2018). "China eyes Vanuatu military base in plan with global ramifications". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ "Vanuatu lawmakers elect Natapei as prime minister". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. 22 September 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ↑ "State of emergency declared in Vanuatu's capital after two deaths". Radio New Zealand International. 4 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- ↑ "Govt numbers remain intact". Vanuatu Daily Post. 1 June 2010.

- ↑ "PM Natapei defeats motion with 36 MPs". Vanuatu Daily Post. 11 December 2009.

- ↑ "Kilman elected Vanuatu PM – ten days after ouster by court". Radio New Zealand International. 26 June 2011.

- ↑ "Vanuatu Prime Minister, facing no confidence vote, resigns". Radio New Zealand International. 21 March 2013. Archived from the original on 23 December 2022.

- ↑ "Vanuatu's Parliament Pass Bill in Support for West Papua". Government of Vanuatu. Archived from the original on 24 July 2010.

- ↑ "Vanuatu to seek observer status for West Papua at MSG and PIF leaders summits". Pacific Scoop. 22 June 2010. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019.

- ↑ "Prime Minister Carcasses' dilemma at the helm". Vanuatu Daily Post. 28 March 2013. Archived from the original on 22 April 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ↑ "Watchdog applauds clean-out of Vanuatu's diplomatic sector". Radio New Zealand International. 13 June 2013. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Pam: Vanuatu death toll rises to 16 as relief effort continues". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 21 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "Calls for Vanuatu PM to step down in wake of MPs' jailing". Radio New Zealand. 22 October 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ "Vanuatu Opposition ready to assist President". Radio New Zealand. 13 October 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ "Vanuatu elects new prime minister as country reels from devastating cyclone". The Guardian. 20 April 2020. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020.

- ↑ Wasuka, Evan (18 March 2020). "Supreme Court to hear 'abuse of process' application in PM's alleged bribery case". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- ↑ "Asia Today: Hong Kong, Singapore OK quarantine-free travel". AP News. Associated Press. 11 November 2020. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020.

- ↑ Bamford, Luci (4 October 2023). "Vanuatu becomes first in the Pacific to set a path towards cervical cancer elimination". Kirby Institute.

- ↑ "Facts & Figures". independence.gov.vu. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The Peace Corps Welcomes You to Vanuatu" (PDF). Peace Corps. May 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Background Note: Vanuatu". Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. U.S. Department of State. April 2007. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ↑ "Oceania – Vanuatu Summary". SEDAC Socioeconomic Data and Applications Centre. 2000. Archived from the original on 23 June 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- 1 2 "Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (Pacific Islands Applied Geoscience Commission)". SOPAC. Archived from the original on 1 August 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- ↑ "Major Earthquake Jolts Island Nation Vanuatu". indiaserver.com. 11 July 2008. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- ↑ Dinerstein, Eric; et al. (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ↑ Asia Development Bank Vanuatu Economic Report 2009