Serpent, late 18th century Italy. Civic Museum of Modena | |

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names |

|

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 423.213 (labrosones with fingerholes with wide conical bore[1]) |

| Developed | Late 16th century |

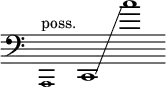

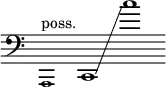

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| Musicians | |

| |

| Builders | |

| |

| Sound sample | |

The serpent is a low-pitched early wind instrument in the brass family developed in the Renaissance era. It has a trombone-like mouthpiece, with tone holes and fingering like a woodwind instrument. It is named for its long, conical bore bent into a snakelike shape, and unlike most brass instruments is made from wood with an outer covering of leather. A distant ancestor of the tuba, the serpent is related to the cornett and was used for bass parts from the 17th to the early 19th centuries.[4]

In the early 19th century, several upright variants were developed and used, until they were superseded first by the ophicleide and ultimately by the valved tuba. After almost entirely disappearing from orchestras, the serpent experienced a renewed interest in historically informed performance practice in the mid-20th century. Several contemporary works have been commissioned and composed, and serpents are again made by a small number of contemporary manufacturers. The sound of a serpent is somewhere between a bassoon and a euphonium, and it is typically played in a seated position, with the instrument resting upright between the player's knees.

Construction

Although closely related to the cornett, the serpent has thinner walls, a more conical bore, and no thumb-hole.[5] The original serpent was typically built from hardwood, usually walnut or other tonewoods like maple, cherry, or pear, or sometimes softer woods like poplar (a very small number were made entirely from copper or brass). The whole instrument is assembled from several curved tubular wooden segments, each made by gluing two hollowed halves together. These segments are then glued and bound with an outer covering of leather. Sometimes the instrument is made from bonding two S-shaped halves, each carved from a single large piece of wood.[6]

The instrument uses a mouthpiece about the same size as a tenor trombone mouthpiece, originally made from ivory, horn or wood, which fits into the bocal or crook, a small length of brass tubing that emerges from the top wooden segment.[6]

The serpent has six tone holes, in two groups of three, fingered by each hand.[6] It is difficult to play the instrument with correct intonation, due in large part to the positions of the tone holes.[7] They were arranged largely to be accessible to the player's fingers, rather than in acoustically correct positions, which would have placed some of them out of reach.[8][9] While early serpents were keyless, later instruments added keys for additional holes out of reach of the fingers to improve intonation, and extend range.[6]

Modern replicas are made by several specialist instrument makers, employing acoustic analysis and modern fabrication materials and techniques to further improve the serpent's intonation. Some of these techniques include use of modern composite materials and polymers, 3D printing, and changing the placement of tone holes.[3] Swiss serpent maker Stephan Berger in collaboration with French jazz musician Michel Godard has developed an improved serpent based on studying well-preserved museum instruments, and also makes a lightweight model from carbon fibre.[10] English serpent player and musicologist Clifford Bevan remarks that Berger's instruments are much improved, finally allowing players to approach the serpent "in partnership rather than in combat".[8]

Sizes

.png.webp)

The majority of surviving specimens in museums and private collections were built in 8′ C, thus having a total tubing length of about 8 feet (2.4 m). A few slightly smaller specimens were built in D, and military serpents could sometimes vary in pitch between D♭ and B♭.[7]

Soprano serpent

A soprano serpent, or worm, first appeared in the 1980s; there is no repertoire or other evidence of their historical existence. Built an octave higher than a serpent in 4′ C, it was first made as a novelty instrument by English early music specialist and instrument maker Christopher Monk.[12][13]

Contrabass serpent

The contrabass serpent, nicknamed the anaconda and built in 16′ C one octave below the serpent, was an English invention of the mid-19th century with no historical repertoire.[14] The prototype instrument was built c. 1840 by Joseph and Richard Wood in Huddersfield as a double-sized English military serpent, and survives in the University of Edinburgh museum collection.[15][11] During the serpent's modern revival, two more contrabass serpents were built in the 1990s by Christopher Monk's workshop. Based on the original serpent ordinaire form, they were called "George" and "George II".[13] The first, commissioned by musicologist and serpent player Philip Palmer, is now owned by American trombonist and serpent player Douglas Yeo and features in some of his serpent recordings.[16]

History

There is little direct material or documentary evidence for the exact origin of the serpent. French historian Jean Lebeuf claimed in his 1743 work Mémoires Concernant l'Histoire Ecclésiastique et Civile d’Auxerre that the serpent was invented in 1590 by Edmé Guillaume, a clergyman in Auxerre, France.[17] Although this account is often accepted, some scholars suppose instead that the serpent evolved from the large, S-shaped bass cornetts that were in use in Italy in the 16th century.[18] It was certainly used in France since the early 17th century to strengthen the cantus firmus and bass voices of choirs in plainchant.[19] This original traditional serpent was known as the serpent ordinaire or serpent d'église (lit. 'ordinary serpent' or 'church serpent'). Around the middle of the 18th century, the serpent began to appear in chamber ensembles, and later in orchestras. Mozart used two serpents in the orchestra for his 1771 opera Ascanio in Alba.[20]

Military serpents

Towards the end of the 18th century, the increased popularity of the serpent in military bands drove the subsequent development of the instrument to accommodate marching or mounted players. In England, a distinct military serpent was developed which had a more compact shape with tighter curves, added extra keys to improve its intonation, and metal braces between the bends to increase its rigidity and durability.[4] In France around the same time several makers produced a serpent militaire initially developed by Piffault (by whose name they are also known) that arranges the tubing vertically with an upward turned bell, reminiscent of a tenor saxophone.[13]

Upright serpents and bass horns

Several vertical configurations of the serpent, generally known as upright serpents (French: serpent droit) or bass horns, were developed in the early 19th century. Retaining the same six tone holes and fingering of the original serpent, these instruments resemble the bassoon, with jointed straight tubes that fit into a short U-shaped butt joint, and an upward-pointing bell.[4]

Basson russe

Among the first of the upright serpents to appear was the basson russe, lit. 'Russian bassoon', although it was neither Russian nor a bassoon. The name is possibly a corruption of basson prusse since they were taken up by the Prussian army bands of the time.[21] These instruments were built mostly in Lyon and often had the buccin-style decorative zoomorphic bells popular in France at the time, shaped and painted like a dragon or serpent head.[4] Appearing around the same time in military bands was the serpent à pavillon (lit. 'bell serpent') which had a normal brass instrument bell, similar in flare to the later ophicleide.[22]

English bass horn

The English bass horn, developed by French musician and inventor Louis Alexandre Frichot in London in 1799, had an all-metal V-shaped construction, described by German composer Felix Mendelssohn as resembling a watering can. He admired its sound however, and wrote for the instrument in several of his works, including his fifth symphony and the overture to A Midsummer Night's Dream.[4] The bass horn was popular in civic and military bands in Britain and Ireland, and also spread back into orchestras in Europe, where it influenced the inventors of both the ophicleide and later the Baß-Tuba.[23]

Early cimbasso

The serpent appears as serpentone in early 19th century Italian operatic scores by composers such as Spontini, Rossini, and Bellini.[24] In Italy it was replaced by the cimbasso, a loose term that referred to several instruments; initially an upright serpent similar to the basson russe, then the ophicleide, early forms of valved tuba (pelittone, bombardone), and finally by the time of Verdi's opera Otello (1887), a valve contrabass trombone.[25]

Other upright serpents

In Paris in 1823, Forveille invented his eponymous serpent Forveille, an upright serpent with an enlarged bell section influenced by the (then newly invented) ophicleide. It is distinguished by being made from wood, brass tubing being used only for the leadpipe and first bend.[26] It became popular in bands for its improved intonation and sound quality.[4] In 1828 Jean-Baptiste Coëffet patented his ophimonocleide ("snake with one key"), one of the last forms of the upright serpent.[24] It solved a perennial problem of the serpent, its difficult and indistinct B♮ notes. The instrument is built a semitone lower in B♮ and adds a large open tone hole that keeps the instrument in C until its key is pressed, closing the tone hole and producing a clear and resonant B♮.[27]

Contemporary revival

The era of upright serpents was brief, spanning the first half of the 19th century from their invention to their replacement by the ophicleide and subsequent valved brass instruments.[28] German opera composer Richard Wagner used a serpent as a third bassoon in his 1840 opera Rienzi, but by the 1869 première of his Der Ring des Nibelungen cycle he was writing his lowest brass parts for tuba and contrabass trombone.[29] Consequently, the serpent had all but disappeared from ensembles by 1900.

The serpent has enjoyed a modern revival of interest and manufacture since the mid-20th century. Christopher Monk began building his own replica cornetts and serpents and playing them in historically informed performances. In 1968 he and a colleague devised a method of constructing them inexpensively from a composite wood-resin material, which helped to raise interest in these instruments and increase their availability. In 1976 he established the London Serpent Trio with English players Andrew van der Beek and Alan Lumsden, performing new works and historical arrangements, both serious and whimsical, throughout Europe and North America.[30][31] At the same time in France, historical instrument specialist Bernard Fourtet and jazz musician Michel Godard began promoting use of the serpent and established an academy for young serpent players.[32]

Range and performance

There is no real standard for the serpent's range, which varies according to the instrument and the player, but it typically covers the three octaves from C2 two octaves below middle C to C5. Good players can also extend the range downwards to A1 or even F1 by fingering the low C note with all holes covered, and "lipping" down with the embouchure.[33]

Repertoire

Serpents were originally used as an instrument to accompany church choral music, particularly in France. For this purpose, very little was specifically written for the serpent per se; the serpent player would simply play the cantus firmus, or bass line.[17] The serpent began to be called for in orchestras by opera composers in the mid-to-late 18th century, and their subsequent adoption in military bands prompted the publication of several method books, fingering charts and etudes, including duets for student and teacher.[34]

Several notable composers included a serpent in their orchestral works, including:

- George Frideric Handel - Music for the Royal Fireworks

- Ludwig van Beethoven - Military March in D Major, WoO 24

- Hector Berlioz - Symphonie Fantastique (original draft, later abandoned)

- Niccolò Paganini - Violin Concerto No. 2 in B Minor “La Campanella”

- Felix Mendelssohn - Overture: Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage

- Richard Wagner - Rienzi

After disappearing almost entirely, the serpent began to reappear in the mid-20th century, in film scores and new period instrument chamber ensembles. American film composer Bernard Herrmann used a serpent in the scores of White Witch Doctor (1953) and Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959), as did Jerry Goldsmith in his score for Alien (1979).[35]

In jazz music, French musician and tubist Michel Godard has incorporated the serpent into his work.

Modern works for the instrument include a concerto for serpent and orchestra by English composer Simon Proctor, commissioned in 1987 to mark the first International Serpent Festival in South Carolina, where it was premièred by London Serpent Trio member Alan Lumsden in 1989.[35][36] Also premièred at the festival was comic composer Peter Schickele's P.D.Q. Bach piece "O Serpent" written for the London Serpent Trio and an ensemble of vocalists.[37][38] Douglas Yeo premièred "Temptation" for serpent and string quartet, written by his Boston Symphony Orchestra colleague, trombonist and composer Norman Bolter, at the 1999 International Trombone Festival in Potsdam, New York.[39][40] Yeo also premièred a serpent concerto in 2008 by American composer Gordon W. Bowie entitled "Old Dances in New Shoes".[41] Italian composer Luigi Morleo wrote "Diversità: NO LIMIT", a concerto for serpent and strings, which premièred in Monopoli, Italy in 2012.[42]

Players

- Clifford Bevan, musicologist, member of the London Serpent Trio[43]

- Bernard Fourtet, French early music specialist

- Michel Godard, jazz musician, tubist, serpent player

- Phil Humphries, London Serpent Trio, New London Consort[43]

- Alan Lumsden, London Serpent Trio

- Andrew van der Beek, London Serpent Trio

- Steve Wick, tubist, professor of Serpent at Royal Academy of Music, London Serpent Trio[43]

- Douglas Yeo, Boston Symphony Orchestra (retired), bass trombonist, serpent and ophicleide player

In popular culture

- The prop used for the titular horn in the 1956 British film The Case of the Mukkinese Battle-Horn was based on a serpent.[44]

- A prop was used in the 1999 film of A Christmas Carol starring Patrick Stewart. It was featured in the scene during Fezziwig’s Christmas party.

- Serpents appear in the music video for the 2000 single "Frontier Psychiatrist" from the album Since I Left You by Australian group The Avalanches.[45]

References

- ↑ "423.213 Labrosones with fingerholes, with (wider) conical bore". MIMO Hornbostel-Sachs Classification. Musical Instrument Museums Online. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- 1 2 Herbert, Myers & Wallace 2019, p. 490, Appendix 2: The Ranges of Labrosones.

- 1 2

- "EMS Serpent in C by Early Music Shop". Saltaire: Early Music Shop. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- "SBerger Originalserpent" (in German). Les Bois: Stephan Berger Erna Suter. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- "Serpents and tenor cornett". Christopher Monk Instruments. Jeremy West. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- Ribo, Pierre. "Fabrication" (in French). Brussels: Serpent Ribo. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yeo 2021, p. 128–31, "serpent".

- ↑ Bevan 2000, p. 64.

- 1 2 3 4 Bevan 2000, p. 66.

- 1 2 Bevan 2000, p. 74–75.

- 1 2 Herbert, Myers & Wallace 2019, p. 373, "Serpent".

- ↑ Yeo 2019, p. 9.

- ↑ "Le serpent se fait une nouvelle peau" [The serpent gets a new skin]. Trémolo Magazine (in French). May 2021. pp. 26–31. Archived from the original on 30 May 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- 1 2 ""Contrabass serpent, nominal pitch: 16-ft C"". Musical Instruments Museums Edinburgh. St Cecilia's Hall: University of Edinburgh. accession number: L 2929. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ↑ Yeo 2021, p. 170, "worm".

- 1 2 3 Bevan 2000, p. 79.

- ↑ Bevan 2000, p. 77–79.

- ↑ Pegge, R. Morley (May 1959). "The 'Anaconda'". The Galpin Society Journal. Galpin Society. 12: 53–56. doi:10.2307/841945. JSTOR 841945. Archived from the original on 18 May 2023. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- ↑ Yeo, Douglas (2003). Le Monde du Serpent (CD booklet). Berlioz Historic Brass. BHB CD101. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- 1 2 Bevan 2000, p. 65.

- ↑ Herbert Heyde (2007). "Zoomorphic and Theatrical Musical Instruments in the Late Italian Renaissance and Baroque Eras". In Renato Meucci; Franca Falletti; Gabriele Rossi Rognoni (eds.). Marvels of sound and beauty: Italian Baroque musical instruments. Florence: Giunti Editore. ISBN 978-88-09-05395-3. LCCN 2008410070. OCLC 316434285. OL 16893261M. Wikidata Q113004406.

- ↑ Christopher Holman (November 2017). "Rhythm and metre in French Classical plainchant". Early Music. 45 (4): 657–64. doi:10.1093/em/cax087.

- ↑ Don L. Smithers (May 1992). "Mozart's Orchestral Brass". Early Music. Oxford University Press. 20 (2): 254–65. doi:10.1093/earlyj/XX.2.254. JSTOR 3127882.

- ↑ Bevan 2000, p. 81.

- ↑ Kridel, Craig (2003). "Questions and Answers: Bass Horns and Russian Bassoons" (PDF). ITEA Journal. International Tuba Euphonium Association. 30 (4): 73–5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ↑ Bevan 2000, p. 86–89.

- 1 2 Touroude, José-Daniel (9 November 2011). "Compte rendu du colloque "le serpent sans sornettes" du 6 et 7 septembre 2011 aux Invalides à Paris". Archives Musique, Facteurs, Marchands, Luthiers (in French). Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ↑ Meucci 1996, p. 158.

- ↑ Bevan 2000, p. 82.

- ↑ Kridel, Craig (2019). "The Ophimonocleide: Folly or Genius?" (PDF). ITEA Journal. International Tuba Euphonium Association. 46 (2): 30–3. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ↑ Bevan 2000, p. 83, 89.

- ↑ Herbert & Wallace 1997, p. 150, The low brass.

- ↑ Bevan 2000, p. 122.

- ↑ van der Beek, Andrew (20 July 1991). "Obituary: Christopher Monk". The Independent. Retrieved 29 May 2023 – via Lacock.

- ↑ Ribo, Pierre. "Historie" (in French). Brussels: Serpent Ribo. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- ↑ Herbert, Myers & Wallace 2019, p. 371, "Serpent".

- ↑ Yeo 2019, p. 10.

- 1 2 Bevan 2000, p. 125.

- ↑ Angel, Amanda (28 January 2013). "Top Five Snakes on a Concert Stage". WQXR. New York Public Radio. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ Schickele, Peter (27 December 2005). "P.D.Q. Bach: A 40-Year Rretrogressive" (PDF) (programme notes). schickele.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ↑ Yeo, Douglas. "P.D.Q. Bach and American Serpent Players". yeodoug.com. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ Kridel, Craig (2009). "New Wine for Old Bottles" (PDF). ITEA Journal. International Tuba Euphonium Association. 37 (1): 48–50. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

- ↑ Yeo, Douglas. "Tempted by a Serpent". yeodoug.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ Eichler, Jeremy (25 November 2008). "A serpentine member of orchestras past". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Morleo, Luigi. "Diversità: NO LIMIT". Paris: Babel Scores. Archived from the original on 29 May 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Personnel". The London Serpent Trio. White Cottage Websites. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ↑ Bevan 2000, p. 120.

- ↑ The Avalanches (2000). Frontier Psychiatrist – Official HD Video (music video) (published 2009). Retrieved 17 June 2023 – via YouTube.

Bibliography

- Bevan, Clifford (2000). "Chapter 2: Serpents and bass horns". The Tuba Family (2nd ed.). Winchester: Piccolo Press. p. 63–126. ISBN 1-872203-30-2. OCLC 993463927. OL 19533420M. Wikidata Q111040769.

- Herbert, Trevor; Myers, Arnold; Wallace, John, eds. (2019). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Brass Instruments. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316841273. ISBN 978-1-316-63185-0. OCLC 1038492212. OL 34730943M. Wikidata Q114571908.

- Herbert, Trevor; Wallace, John, eds. (1997). The Cambridge Companion to Brass Instruments. Cambridge Companions. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521563437. ISBN 978-1-139-00203-5. OCLC 460517551. OL 34482695M. Wikidata Q112852613.

- Meucci, Renato (1996). Translated by William Waterhouse. "The Cimbasso and Related Instruments in 19th-Century Italy". The Galpin Society Journal (published March 1996). 49: 143–179. ISSN 0072-0127. JSTOR 842397. Wikidata Q111077162.

- Yeo, Douglas (2019). Serpents bass horns and ophicleides at the Bate Collection. University of Oxford. ISBN 978-0-9930442-2-9. Wikidata Q121457145.

- Yeo, Douglas (2021). An Illustrated Dictionary for the Modern Trombone, Tuba, and Euphonium Player. Dictionaries for the Modern Musician. Peterson, Lennie (illustrator). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-538-15966-8. LCCN 2021020757. OCLC 1249799159. OL 34132790M. Wikidata Q111040546.

External links

Media related to Serpents at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Serpents at Wikimedia Commons- Serpents in the Bate Collection, University of Oxford.

- The Serpent Website – an online reference for everything serpent-related.

- serpent.instrument – serpent website (in French) by Volny Hostiou, French tubist and serpent specialist.

- Recordings of orchestral excerpts by Jack Adler-McKean, including serpent as well as bass horn, early cimbasso, and ophicleide.

_MET_DP249508.jpg.webp)