A polymath (Greek: πολυμαθής, romanized: polymathēs, lit. 'having learned much'; Latin: homo universalis, lit. 'universal human')[1] is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems.

In Western Europe, the first work to use the term polymathy in its title (De Polymathia tractatio: integri operis de studiis veterum) was published in 1603 by Johann von Wowern, a Hamburg philosopher.[2][3][4] Von Wowern defined polymathy as "knowledge of various matters, drawn from all kinds of studies ... ranging freely through all the fields of the disciplines, as far as the human mind, with unwearied industry, is able to pursue them".[2] Von Wowern lists erudition, literature, philology, philomathy, and polyhistory as synonyms.

The earliest recorded use of the term in the English language is from 1624, in the second edition of The Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton;[5] the form polymathist is slightly older, first appearing in the Diatribae upon the first part of the late History of Tithes of Richard Montagu in 1621.[6] Use in English of the similar term polyhistor dates from the late 16th century.[7]

Polymaths include the great scholars and thinkers of the Renaissance and Enlightenment, who excelled at several fields in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and the arts. In the Italian Renaissance, the idea of the polymath was allegedly expressed by Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), a polymath himself, in the statement that "a man can do all things if he will".[8] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz has often been seen as a polymath. Al-Biruni was also a polymath.[9] Other well-known and celebrated polymaths include Leonardo da Vinci, Hildegard of Bingen, Ibn al-Haytham, Rabindranath Tagore, Mikhail Lomonosov, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Alan Turing, Benjamin Franklin, John von Neumann, Omar Khayyam, Charles Sanders Peirce, Henri Poincaré, Isaac Asimov, Nicolaus Copernicus, René Descartes, Aristotle, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Averroes, Archimedes, George Washington Carver, Hypatia, Blaise Pascal, Africanus Horton, Wang Wei, Isaac Newton, Leonhard Euler, Émilie du Châtelet, Nikola Tesla, Thomas Edison, Bertrand Russell, Thomas Young, Sequoyah, Thomas Jefferson and Pierre-Simon Laplace.

Embodying a basic tenet of Renaissance humanism that humans are limitless in their capacity for development, the concept led to the notion that people should embrace all knowledge and develop their capacities as fully as possible. This is expressed in the term Renaissance man, often applied to the gifted people of that age who sought to develop their abilities in all areas of accomplishment: intellectual, artistic, social, physical, and spiritual.

Renaissance man

The term "Renaissance man" was first recorded in written English in the early 20th century.[10] It is used to refer to great thinkers living before, during, or after the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci has often been described as the archetype of the Renaissance man, a man of "unquenchable curiosity" and "feverishly inventive imagination".[11] Many notable polymaths[lower-alpha 1] lived during the Renaissance period, a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th through to the 17th century that began in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spread to the rest of Europe. These polymaths had a rounded approach to education that reflected the ideals of the humanists of the time. A gentleman or courtier of that era was expected to speak several languages, play a musical instrument, write poetry, and so on, thus fulfilling the Renaissance ideal.

The idea of a universal education was essential to achieving polymath ability, hence the word university was used to describe a seat of learning. However, the original Latin word universitas refers in general to "a number of persons associated into one body, a society, company, community, guild, corporation, etc".[12] At this time, universities did not specialize in specific areas, but rather trained students in a broad array of science, philosophy, and theology. This universal education gave them a grounding from which they could continue into apprenticeship toward becoming a master of a specific field.

When someone is called a "Renaissance man" today, it is meant that rather than simply having broad interests or superficial knowledge in several fields, the individual possesses a more profound knowledge and a proficiency, or even an expertise, in at least some of those fields.[13]

Some dictionaries use the term "Renaissance man" to describe someone with many interests or talents,[14] while others give a meaning restricted to the Renaissance and more closely related to Renaissance ideals.

In academia

Robert Root-Bernstein and colleagues

Robert Root-Bernstein is considered the principal responsible for rekindling interest in polymathy in the scientific community.[15][16] His works emphasize the contrast between the polymath and two other types: the specialist and the dilettante. The specialist demonstrates depth but lacks breadth of knowledge. The dilettante demonstrates superficial breadth but tends to acquire skills merely "for their own sake without regard to understanding the broader applications or implications and without integrating it".[17]: 857 Conversely, the polymath is a person with a level of expertise that is able to "put a significant amount of time and effort into their avocations and find ways to use their multiple interests to inform their vocations".[18]: 857 [19][20][21][22]

A key point in the work of Root-Bernstein and colleagues is the argument in favor of the universality of the creative process. That is, although creative products, such as a painting, a mathematical model or a poem, can be domain-specific, at the level of the creative process, the mental tools that lead to the generation of creative ideas are the same, be it in the arts or science.[20] These mental tools are sometimes called intuitive tools of thinking. It is therefore not surprising that many of the most innovative scientists have serious hobbies or interests in artistic activities, and that some of the most innovative artists have an interest or hobbies in the sciences.[18][21][23][24]

Root-Bernstein and colleagues' research is an important counterpoint to the claim by some psychologists that creativity is a domain-specific phenomenon. Through their research, Root-Bernstein and colleagues conclude that there are certain comprehensive thinking skills and tools that cross the barrier of different domains and can foster creative thinking: "[creativity researchers] who discuss integrating ideas from diverse fields as the basis of creative giftedness ask not 'who is creative?' but 'what is the basis of creative thinking?' From the polymathy perspective, giftedness is the ability to combine disparate (or even apparently contradictory) ideas, sets of problems, skills, talents, and knowledge in novel and useful ways. Polymathy is therefore the main source of any individual's creative potential".[17]: 857 In "Life Stages of Creativity", Robert and Michèle Root-Bernstein suggest six typologies of creative life stages. These typologies based on real creative production records first published by Root-Bernstein, Bernstein, and Garnier (1993).

- Type 1 represents people who specialize in developing one major talent early in life (e.g., prodigies) and successfully exploit that talent exclusively for the rest of their lives.

- Type 2 individuals explore a range of different creative activities (e.g., through worldplay or a variety of hobbies) and then settle on exploiting one of these for the rest of their lives.

- Type 3 people are polymathic from the outset and manage to juggle multiple careers simultaneously so that their creativity pattern is constantly varied.

- Type 4 creators are recognized early for one major talent (e.g., math or music) but go on to explore additional creative outlets, diversifying their productivity with age.

- Type 5 creators devote themselves serially to one creative field after another.

- Type 6 people develop diversified creative skills early and then, like Type 5 individuals, explore these serially, one at a time.

Finally, his studies suggest that understanding polymathy and learning from polymathic exemplars can help structure a new model of education that better promotes creativity and innovation: "we must focus education on principles, methods, and skills that will serve them [students] in learning and creating across many disciplines, multiple careers, and succeeding life stages".[25]: 161

Peter Burke

Peter Burke, Professor Emeritus of Cultural History and Fellow of Emmanuel College at Cambridge, discussed the theme of polymathy in some of his works. He has presented a comprehensive historical overview of the ascension and decline of the polymath as, what he calls, an "intellectual species".[26][27][28]

He observes that in ancient and medieval times, scholars did not have to specialize. However, from the 17th century on, the rapid rise of new knowledge in the Western world—both from the systematic investigation of the natural world and from the flow of information coming from other parts of the world—was making it increasingly difficult for individual scholars to master as many disciplines as before. Thus, an intellectual retreat of the polymath species occurred: "from knowledge in every [academic] field to knowledge in several fields, and from making original contributions in many fields to a more passive consumption of what has been contributed by others".[29]: 72

Given this change in the intellectual climate, it has since then been more common to find "passive polymaths", who consume knowledge in various domains but make their reputation in one single discipline, than "proper polymaths", who—through a feat of "intellectual heroism"—manage to make serious contributions to several disciplines.

However, Burke warns that in the age of specialization, polymathic people are more necessary than ever, both for synthesis—to paint the big picture—and for analysis. He says: "It takes a polymath to 'mind the gap' and draw attention to the knowledges that may otherwise disappear into the spaces between disciplines, as they are currently defined and organized".[30]: 183

Finally, he suggests that governments and universities should nurture a habitat in which this "endangered species" can survive, offering students and scholars the possibility of interdisciplinary work.

Bharath Sriraman

Bharath Sriraman, of the University of Montana, also investigated the role of polymathy in education. He poses that an ideal education should nurture talent in the classroom and enable individuals to pursue multiple fields of research and appreciate both the aesthetic and structural/scientific connections between mathematics, arts and the sciences.[31]

In 2009, Sriraman published a paper reporting a 3-year study with 120 pre-service mathematics teachers and derived several implications for mathematics pre-service education as well as interdisciplinary education.[16] He utilized a hermeneutic-phenomenological approach to recreate the emotions, voices and struggles of students as they tried to unravel Russell's paradox presented in its linguistic form. They found that those more engaged in solving the paradox also displayed more polymathic thinking traits. He concludes by suggesting that fostering polymathy in the classroom may help students change beliefs, discover structures and open new avenues for interdisciplinary pedagogy.[16]

Michael Araki

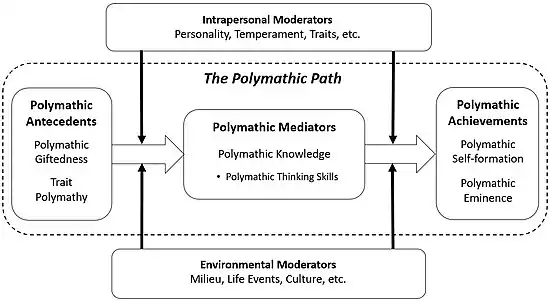

Michael Araki is a professor at Universidade Federal Fluminense in Brazil. He sought to formalize in a general model how the development of polymathy takes place. His Developmental Model of Polymathy (DMP) is presented in a 2018 article with two main objectives:

- organize the elements involved in the process of polymathy development into a structure of relationships that is wed to the approach of polymathy as a life project, and;

- provide an articulation with other well-developed constructs, theories, and models, especially from the fields of giftedness and education.[32]

The model, which was designed to reflect a structural model, has five major components:

- polymathic antecedents

- polymathic mediators

- polymathic achievements

- intrapersonal moderators

- environmental moderators[32]

Regarding the definition of the term polymathy, the researcher, through an analysis of the extant literature, concluded that although there are a multitude of perspectives on polymathy, most of them ascertain that polymathy entails three core elements: breadth, depth and integration.[32][33][34]

Breadth refers to comprehensiveness, extension and diversity of knowledge. It is contrasted with the idea of narrowness, specialization, and the restriction of one's expertise to a limited domain. The possession of comprehensive knowledge at very disparate areas is a hallmark of the greatest polymaths.

Depth refers to the vertical accumulation of knowledge and the degree of elaboration or sophistication of one's sets of one's conceptual network. Like Robert Root-Bernstein, Araki uses the concept of dilettancy as a contrast to the idea of profound learning that polymathy entails.

Integration, although not explicit in most definitions of polymathy, is also a core component of polymathy according to the author. Integration involves the capacity of connecting, articulating, concatenating or synthesizing different conceptual networks, which in non-polymathic persons might be segregated. In addition, integration can happen at the personality level, when the person is able to integrate their diverse activities in a synergic whole, which can also mean a psychic (motivational, emotional and cognitive) integration.

Finally, the author also suggests that, via a psychoeconomic approach, polymathy can be seen as a "life project". That is, depending on a person's temperament, endowments, personality, social situation and opportunities (or lack thereof), the project of a polymathic self-formation may present itself to the person as more or less alluring and more or less feasible to be pursued.[32]

Kaufman, Beghetto and colleagues

James C. Kaufman, from the Neag School of Education at the University of Connecticut, and Ronald A. Beghetto, from the same university, investigated the possibility that everyone could have the potential for polymathy as well as the issue of the domain-generality or domain-specificity of creativity.[35][36]

Based on their earlier four-c model of creativity, Beghetto and Kaufman[37][38] proposed a typology of polymathy, ranging from the ubiquitous mini-c polymathy to the eminent but rare Big-C polymathy, as well as a model with some requirements for a person (polymath or not) to be able to reach the highest levels of creative accomplishment. They account for three general requirements—intelligence, motivation to be creative, and an environment that allows creative expression—that are needed for any attempt at creativity to succeed. Then, depending on the domain of choice, more specific abilities will be required. The more that one's abilities and interests match the requirements of a domain, the better. While some will develop their specific skills and motivations for specific domains, polymathic people will display intrinsic motivation (and the ability) to pursue a variety of subject matters across different domains.[38]

Regarding the interplay of polymathy and education, they suggest that rather than asking whether every student has multicreative potential, educators might more actively nurture the multicreative potential of their students. As an example, the authors cite that teachers should encourage students to make connections across disciplines, use different forms of media to express their reasoning/understanding (e.g., drawings, movies, and other forms of visual media).[35]

Waqas Ahmed

In his 2018 book The Polymath, British author Waqas Ahmed defines polymaths as those who have made significant contributions to at least three different fields.[16] Rather than seeing polymaths as exceptionally gifted, he argues that every human being has the potential to become one: that people naturally have multiple interests and talents.[39] He contrasts this polymathic nature against what he calls "the cult of specialisation".[40] For example, education systems stifle this nature by forcing learners to specialise in narrow topics.[39] The book argues that specialisation encouraged by the production lines of the Industrial Revolution is counter-productive both to the individual and wider society. It suggests that the complex problems of the 21st century need the versatility, creativity, and broad perspectives characteristic of polymaths.[39]

For individuals, Ahmed says, specialisation is dehumanising and stifles their full range of expression whereas polymathy "is a powerful means to social and intellectual emancipation" which enables a more fulfilling life.[41] In terms of social progress, he argues that answers to specific problems often come from combining knowledge and skills from multiple areas, and that many important problems are multi-dimensional in nature and cannot be fully understood through one specialism.[41] Rather than interpreting polymathy as a mix of occupations or of intellectual interests, Ahmed urges a breaking of the "thinker"/"doer" dichotomy and the art/science dichotomy. He argues that an orientation towards action and towards thinking support each other, and that human beings flourish by pursuing a diversity of experiences as well as a diversity of knowledge. He observes that successful people in many fields have cited hobbies and other "peripheral" activities as supplying skills or insights that helped them succeed.[42]

Ahmed examines evidence suggesting that developing multiple talents and perspectives is helpful for success in a highly specialised field. He cites a study of Nobel Prize-winning scientists which found them 25 times more likely to sing, dance, or act than average scientists.[43] Another study found that children scored higher in IQ tests after having drum lessons, and he uses such research to argue that diversity of domains can enhance a person's general intelligence.[44]

Ahmed cites many historical claims for the advantages of polymathy. Some of these are about general intellectual abilities that polymaths apply across multiple domains. For example, Aristotle wrote that full understanding of a topic requires, in addition to subject knowledge, a general critical thinking ability that can assess how that knowledge was arrived at.[45] Another advantage of a polymathic mindset is in the application of multiple approaches to understanding a single issue. Ahmed cites biologist E. O. Wilson's view that reality is approached not by a single academic discipline but via a consilience between them.[46] One argument for studying multiple approaches is that it leads to open-mindedness. Within any one perspective, a question may seem to have a straightforward, settled answer. Someone aware of different, contrasting answers will be more open-minded and aware of the limitations of their own knowledge. The importance of recognising these limitations is a theme that Ahmed finds in many thinkers, including Confucius, ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, and Nicolas of Cusa. He calls it "the essential mark of the polymath."[46] A further argument for multiple approaches is that a polymath does not see diverse approaches as diverse, because they see connections where other people see differences. For example da Vinci advanced multiple fields by applying mathematical principles to each.[47]

Related terms

Aside from Renaissance man, similar terms in use are homo universalis (Latin) and uomo universale (Italian), which translate to 'universal man'.[1] The related term generalist—contrasted with a specialist—is used to describe a person with a general approach to knowledge.

The term universal genius or versatile genius is also used, with Leonardo da Vinci as the prime example again. The term is used especially for people who made lasting contributions in at least one of the fields in which they were actively involved and when they took a universality of approach.

When a person is described as having encyclopedic knowledge, they exhibit a vast scope of knowledge. However, this designation may be anachronistic in the case of persons such as Eratosthenes, whose reputation for having encyclopedic knowledge predates the existence of any encyclopedic object.

See also

References and notes

- ↑ Though numerous figures in history could be considered to be polymaths, they are not listed here, as they are not only too numerous to list, but also as the definition of any one figure as a polymath is disputable, due to the term's loosely-defined nature, there being no given set of characteristics outside of a person having a wide range of learning across a number of different disciplines; many also did not identify as polymaths, the term having only come into existence in the early 17th century.

- 1 2 "Ask The Philosopher: Tim Soutphommasane – The quest for renaissance man". The Australian. 10 April 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- 1 2 Murphy, Kathryn (2014). "Robert Burton and the problems of polymathy". Renaissance Studies. 28 (2): 279. doi:10.1111/rest.12054. S2CID 162763342. Archived from the original on 30 April 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ Burke, Peter (2011). "O polímata: a história cultural e social de um tipo intellectual". Leitura: Teoria & Prática. ISSN 0102-387X.

- ↑ Wower, Johann (1665). De Polymathia tractatio: integri operis de studiis veterum.

- ↑ "polymath, n. and adj. Archived 8 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine". OED Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Accessed December 2019.

- ↑ "polymathist, n.". OED Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Accessed December 2019.

- ↑ "polyhistor, n.". OED Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Accessed December 2019.

- ↑ "Renaissance man – Definition, Characteristics, & Examples". Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- ↑ "BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

BĪRŪNĪ, ABŪ RAYḤĀN MOḤAMMAD b. Aḥmad (362/973- after 442/1050), scholar and polymath of the period of the late Samanids and early Ghaznavids and one of the two greatest intellectual figures of his time in the eastern lands of the Muslim world, the other being Ebn Sīnā (Avicenna).

- ↑ Harper, Daniel (2001). "Online Etymology Dictionary". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ↑ Gardner, Helen (1970). Art through the Ages. New York, Harcourt, Brace & World. pp. 450–456. ISBN 9780155037526.

- ↑ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1966) [1879], A Latin Dictionary, Oxford: Clarendon Press

- ↑ "Renaissance man — Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". M-w.com. Archived from the original on 18 May 2006. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ↑ "Oxford concise dictionary". Askoxford.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ↑ Shavinina, L. (2013). How to develop innovators? Innovation education for the gifted1. Gifted Education International, 29(1), 54–68.

- 1 2 3 4 Sriraman, B. (2009). Mathematical paradoxes as pathways into beliefs and polymathy: An experimental inquiry. ZDM, 41(1-2), 29–38.

- 1 2 R. Root-Bernstein, 2009

- 1 2 Root-Bernstein, R. (2015). Arts and crafts as adjuncts to STEM education to foster creativity in gifted and talented students. Asia Pacific Education Review, 16(2), 203–212.

- ↑ Root-Bernstein, R. (2009). Multiple giftedness in adults: The case of polymaths. In International handbook on giftedness (pp. 853–870). Springer, Dordrecht.

- 1 2 Root-Bernstein, R. (2003). The art of innovation: Polymaths and universality of the creative process. In The international handbook on innovation (pp. 267–278).

- 1 2 Root-Bernstein, R., Allen, L., Beach, L., Bhadula, R., Fast, J., Hosey, C., ... & Podufaly, A. (2008). Arts foster scientific success: Avocations of nobel, national academy, royal society, and sigma xi members. Journal of Psychology of Science and Technology, 1(2), 51–63.

- ↑ Root-Bernstein, R., & Root-Bernstein, M. (2011). Life stages of creativity.

- ↑ Root‐Bernstein, R. S., Bernstein, M., & Gamier, H. (1993). Identification of scientists making long‐term, high‐impact contributions, with notes on their methods of working. Creativity Research Journal, 6(4), 329–343.

- ↑ Root-Bernstein, R. S., Bernstein, M., & Garnier, H. (1995). Correlations between avocations, scientific style, work habits, and professional impact of scientists. Creativity Research Journal, 8(2), 115–137.

- ↑ Root-Bernstein, R., & Root-Bernstein, M. (2017). People, passions, problems: The role of creative exemplars in teaching for creativity. In Creative contradictions in education (pp. 143–164). Springer, Cham.

- ↑ Burke, P. (2012). A social history of knowledge II: From the encyclopaedia to Wikipedia (Vol. 2). Polity.

- ↑ Burke, P. (2010). The polymath: A cultural and social history of an intellectual species. Explorations in cultural history: Essays for Peter McCaffery, 67–79.

- ↑ Burke, Peter (2020). The Polymath: A Cultural History from Leonardo da Vinci to Susan Sontag. Yale University Press. p. 352. ISBN 9780300252088. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2020.

- ↑ Burke, 2010

- ↑ Burke, 2012

- ↑ Sriraman, B., & Dahl, B. (2009). On bringing interdisciplinary ideas to gifted education. In International handbook on giftedness (pp. 1235–1256). Springer, Dordrecht.

- 1 2 3 4 Araki, M. E. (2018). Polymathy: A new outlook. Journal of Genius and Eminence, 3(1), 66–82. Retrieved from: Researchgate.net

- ↑ Araki, M. E. (2015). Polymathic leadership: Theoretical foundation and construct development. (Master's thesis), Pontifícia Universidade Católica, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Retrieved from: researchgate.net Archived 29 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Araki, M. E., & Pires, P. (2019). < Modern Literature on Polymathy: A Brief Review (January 10, 2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3313137

- 1 2 Kaufman, J. C., Beghetto, R. A., Baer, J., & Ivcevic, Z. (2010). Creativity polymathy: What Benjamin Franklin can teach your kindergartener. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(4), 380-387.

- ↑ Kaufman, J. C., Beghetto, R. A., & Baer, J. (2010). Finding young Paul Robeson: Exploring the question of creative polymathy. Innovations in educational psychology, 141–162.

- ↑ Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four c model of creativity. Review of general psychology, 13(1), 1.

- 1 2 Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2009). Do we all have multicreative potential?. ZDM, 41(1–2), 39–44.

- 1 2 3 Robinson, Andrew (11 May 2019). "In pursuit of polymathy". The Lancet. 393 (10184): 1926. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30995-X. S2CID 149445248. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ↑ Ahmed 2018, p. 85.

- 1 2 Ahmed 2018, p. 282-283.

- ↑ Ahmed 2018, pp. 160, 164, 176.

- ↑ Hill, Andrew (11 February 2019). "The hidden benefits of hiring Jacks and Jills of all trades". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ↑ Ahmed 2018, p. 146.

- ↑ Ahmed 2018, p. 148.

- 1 2 Ahmed 2018, p. 134-136.

- ↑ Ahmed 2018, p. 173-174.

Further reading

- Carr, Edward (1 October 2009). "Last Days of the Polymath". Intelligent Life. The Economist Group. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- Edmonds, David (August 2017). Does the world need polymaths? Archived 24 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine, BBC.

- Frost, Martin, "Polymath: A Renaissance Man".

- Grafton, A, "The World of the Polyhistors: Humanism and Encyclopedism", Central European History, 18: 31–47. (1985).

- Jaumann, Herbert, "Was ist ein Polyhistor? Gehversuche auf einem verlassenen Terrain", Studia Leibnitiana, 22: 76–89. (1990) .

- Mikkelsen, Kenneth; Martin, Richard (2016). The Neo-Generalist: Where You Go is Who You Are. London: LID Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9781910649558. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- Mirchandani, Vinnie, "The New Polymath: Profiles in Compound-Technology Innovations" Archived 7 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine, John Wiley & Sons. (2010).

- Sher, Barbara (2007). Refuse to Choose!: A Revolutionary Program for Doing Everything that You Love. [Emmaus, Pa.]: Rodale. ISBN 978-1594866265.

- Twigger, Robert, "Anyone can be a Polymath" We live in a one-track world, but anyone can become a polymath Archived 10 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine Aeon Essays.

- Ahmed, Waqas (2018). The Polymath: Unlocking the Power of Human Versatility. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119508489. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- Waquet, F, (ed.) "Mapping the World of Learning: The 'Polyhistor' of Daniel Georg Morhof" (2000) ISBN 978-3447043991.

- Wiens, Kyle (May 2012). "In defense of polymaths". Harvard Business Review. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- Brown, Vincent Polymath-Info Portal Archived 17 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine.