| |

Other name | Tennessee (colloquially) UT UTK UT Knoxville UTenn |

|---|---|

Former names | Blount College (1794–1807) East Tennessee College (1807–1840) East Tennessee University (1840–1879) |

| Motto | Veritatem cognoscetis, et veritas vos liberabit. (Latin) |

Motto in English | "You will know the truth and the truth shall set you free." On seal: "Agriculture, Commerce" |

| Type | Public land-grant research university |

| Established | September 10, 1794 |

Parent institution | University of Tennessee system |

| Accreditation | SACS |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $1.34 billion (2020)[1] |

| Chancellor | Donde Plowman[2] |

| Provost | John Zomchick[3] |

Academic staff | 1,700+[4] |

Administrative staff | 9,791[4] |

| Students | 36,304 (Fall 2023)[5] |

| Undergraduates | 28,883 (Fall 2023)[5] |

| Postgraduates | 7,421 (Fall 2023)[5] |

| Address | 1212 Volunteer Blvd , , , United States 35°57′6″N 83°55′48″W / 35.95167°N 83.93000°W |

| Campus | Midsize city[6], 600 acres (240 ha)[4] Total, 2,128 acres (861 ha)[7][8][9] |

| Newspaper | The Daily Beacon |

| Colors | Orange and white[10] |

| Nickname | Volunteers & Lady Volunteers |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | Smokey XI |

| Website | www |

The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, (or The University of Tennessee; UT Knoxville; UTK; or colloquially Tennessee or UT) is a public land-grant research university in Knoxville, Tennessee, United States. Founded in 1794, two years before Tennessee became the 16th state, it is the flagship campus of the University of Tennessee system, with ten undergraduate colleges and eleven graduate colleges. It hosts more than 30,000 students from all 50 states and more than 100 foreign countries. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[11]

UT's ties to nearby Oak Ridge National Laboratory, established under UT President Andrew Holt and continued under the UT–Battelle partnership, allow for considerable research opportunities for faculty and students. Also affiliated with the university are the Howard H. Baker Jr. Center for Public Policy, the University of Tennessee Anthropological Research Facility, and the University of Tennessee Arboretum, which occupies 250 acres (100 ha) of nearby Oak Ridge and features hundreds of species of plants indigenous to the region. The university is a direct partner of the University of Tennessee Medical Center, which is one of two Level I trauma centers in East Tennessee.

The University of Tennessee is the only university in the nation to have three presidential papers editing projects. The university holds collections of the papers of all three U.S. presidents from Tennessee—Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Andrew Johnson. Nine of its alumni have been selected as Rhodes Scholars and one alumnus, James M. Buchanan, received the 1986 Nobel Prize in Economics. UT is one of the oldest public universities in the United States and the oldest secular institution west of the Eastern Continental Divide.

History

Founding and early days

On September 10, 1794, two years before Tennessee became a state and at a meeting of the legislature of the Southwest Territory at Knoxville, Blount College was established with a charter.[12] The new, non-sectarian, all-male, white-only institution struggled for 13 years with a small student body and faculty, and in 1807, the school was rechartered as East Tennessee College as a condition of receiving the proceeds from the settlement devised in the Compact of 1806. When Samuel Carrick, its first president and only faculty member, died in 1809, the school was temporarily closed until 1820. When it reopened, it began experiencing growing pains. Thomas Jefferson had previously recommended that the college leave its confining single building in the city and relocate to a place it could spread out. In the summer of 1826 (coincidentally, the year that Thomas Jefferson died), the trustees explored "Barbara Hill" (today known simply as The Hill) as a potential site and relocated there by 1828.[13] In 1840, the college was elevated to East Tennessee University (ETU). The school's status as a religiously non-affiliated institution of higher learning was unusual for the period of time in which it was chartered, and the school is generally recognized as the oldest such establishment of its kind west of the Appalachian Divide.[14]

Reconstruction

Tennessee was a member of the Confederacy in 1862 when the Morrill Act was passed, providing for endowment funds from the sale of federal land to state agricultural colleges. On February 28, 1867, Congress passed a special Act making the State of Tennessee eligible to participate in the Morrill Act of 1862 program. In January 1869, the Reconstruction-era Tennessee state government designated ETU as Tennessee's recipient of the Land-Grant designation and funds.

As a land-grant institution, ETU was bound not to exclude any citizens of the state on the basis of color or race. To get around the requirement, the university chose to pay tuition for Black students to attend a separate institution, Fisk University.[15] The following year, in 1870, the Tennessee Constitution was ratified with a provision, Article XI § 12, that prohibited public schools from enrolling both Black and White students, a policy that remained in place until the 1950s.[15]

In accepting the land grant funds, the university would focus upon instructing students in military, agricultural, and mechanical subjects. ETU eventually received $396,000 as its endowment under the program. Trustees soon approved the establishment of a medical program under the auspices of the Nashville School of Medicine and added advanced degree programs. East Tennessee University was renamed the University of Tennessee in 1879 by the state legislature.[16]

World War II

During World War II, UT was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program which offered students a path to a Navy commission.[17]

Civil rights era

Although the university was required to enroll students of any race or ethnicity as a public, land-grant institution, the Tennessee state constitution prohibited integrated education.[15] Only white students were accepted until 1952, when the first two Black students were allowed to enroll in a graduate program. Even after educational segregation was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education, the university resisted desegregation. Black students could first enroll as undergraduates in 1961.[15]

African-American attorney Rita Sanders Geier filed suit against the state of Tennessee in 1968, alleging that its higher education system remained segregated despite a federal mandate ordering desegregation. She alleged that the opening of a University of Tennessee campus at Nashville would lead to the creation of another predominantly white institution that would strip resources from Tennessee State University, the only state-funded Historically black university. The suit was not settled until 2001, when the Geier Consent Decree resulted in the appropriation of $77 million in state funding to increase diversity among student and faculty populations among all Tennessee institutions of higher learning.[18]

Organization

Administration

The University of Tennessee, Knoxville is the flagship campus of the statewide University of Tennessee system, which is governed by a 12-member board of trustees appointed by the Governor of Tennessee. The Board of Trustees appoints a president to oversee the operations of the system, four campuses, and two statewide institutes.[19] Randy Boyd, a former candidate for governor, is the current president following the retirement of Joseph A. DiPietro.[20] The president appoints, with Board of Trustees approval, chancellors for each campus. The Knoxville campus has been headed by Chancellor Donde Plowman since 2019.[21] Provost and Senior Vice Chancellor John Zomchick is responsible for the academic administration of the Knoxville campus and is a member of the Chancellor's Cabinet.[22]

Campus policing and security is provided by the University of Tennessee Police Department.

Controversy

On December 15, 2016, the UT Board of Trustees confirmed Beverly J. Davenport as the next Chancellor of the Knoxville campus, succeeding Jimmy Cheek. She began her role on February 15, 2017, and was the first female Chancellor of UTK.[23] On May 2, 2018, UT President Joe DiPietro fired Davenport. DiPietro cited poor communication and interpersonal skills, amongst other reasons. The decision received criticism from the student body and faculty, as these reasons were also listed as strengths of Davenport, and why DiPietro chose to hire her a little over one year earlier.[24]

Budget

University of Tennessee Knoxville (2015)[25]

- Educational and General Total: $578,766,711

- Instruction: $263,257,573

- Research: $41,848,637

- Public Service: $11,287,642

- Academic Support: $67,888,051

- Student Services: $39,438,427

- Institutional Support: $45,015,257

- Operation/Maintenance of Physical Plant: $69,694,749

- Scholarships and Fellowships: $59,827,375

- Total budget: $758,407,168

According to the university's 2009 budget, state appropriations increased 26.4 percent from 2000 to 2009, although this amounts to only a 1.1 percent when adjusted for inflation.[26]

University Medical Center

The University of Tennessee Medical Center, administered by University Health Systems and affiliated with the University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine, collaborates with the University of Tennessee Health Science Center to attract and train the majority of its medical staff. Many doctors and nurses at UTMC have integrated careers as teachers and healthcare professionals, and the center promotes itself as the area's only academic, or "teaching hospital".

The University Medical Center is the primary referral center for East Tennessee, Western North Carolina, and Southeastern Kentucky. It is one of three Level I trauma centers in the East Tennessee geographic region. Extensive expansion programs were embarked upon the 1990s and 2000s (decade) and saw the construction of two sprawling additions to the hospital's campus, a new Cancer Institute and a Heart Lung Vascular Institute. The new UT Medical Center Heart Hospital received its first patient on April 27, 2010.[27]

Academics

Admissions

Undergraduate

| Undergraduate admissions statistics | |

|---|---|

| Admit rate | 40.5 ( |

| Yield rate | 33.2 ( |

| Test scores middle 50% | |

| SAT Total | 1240–1400 |

| ACT Composite | 26–31 |

The 2022 annual ranking of U.S. News & World Report categorizes UTK as "more selective".[29] For the Class of 2025 (enrolled fall 2021), UTK received 29,909 applications and accepted 22,413 (74.9%). Of those accepted, 5,948 enrolled, a yield rate (the percentage of accepted students who choose to attend the university) of 26.5%. UTK's 2023 freshman retention rate is 91.1%, with 73.5% going on to graduate from the university within six years.[28]

The enrolled first-year class of 2025 had the following standardized test scores: the middle 50% range (25th percentile – 75th percentile) of SAT scores was 1180–1340, while the middle 50% range of ACT scores was 25–31.[28]

| 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | 49,790 | 36,290 | 29,909 | 25,423 | 21,764 | 20,457 | 18,872 | 17,583 |

| Admits | 20,165 | 24,826 | 22,413 | 19,867 | 17,160 | 15,912 | 14,526 | 13,578 |

| Admit rate | 40.5 | 68.4 | 74.9 | 78.1 | 78.8 | 77.8 | 77.0 | 77.2 |

| Enrolled | 6,694 | 6,846 | 5,948 | 5,512 | 5,254 | 5,215 | 4,895 | 4,851 |

| Yield rate | 33.2 | 27.6 | 26.5 | 27.7 | 30.6 | 32.8 | 33.7 | 35.7 |

| ACT composite* (out of 36) |

26–31 | 25–30 | 25–31 | 25–31 | 24–30 | 25–31 | 25–30 | 24–30 |

| SAT composite* (out of 1600) |

1240–1400 | — | 1180–1340 | 1140–1290 | 1140–1310 | 1150–1330 | 1140–1310 | — |

| * middle 50% range |

Rankings

| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[35] | 117 |

| THE / WSJ[36] | 279 |

| U.S. News & World Report[37] | 103 |

| Washington Monthly[38] | 106 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[39] | 201–300 |

| QS[40] | 446 |

| THE[41] | 301–350 |

| U.S. News & World Report[42] | 218 |

The University of Tennessee was tied for 46th among public universities and tied for 103rd among national universities in the United States by U.S. News & World Report in its 2022 rankings.[43]

The University of Tennessee was ranked as the most LGBTQ-unfriendly university in the United States by The Princeton Review among all 388 institutions it surveyed for its 2023 rankings. The campus Pride Center has been defunded and vandalized several times.[44]

Research

The total research endowment of the UT Knoxville campus was $127,983,213 for FY 2006. UT Knoxville boasts several faculty who are among the leading contributors to their fields, including Harry McSween, generally recognized as one of the world's leading experts in the study of meteorites and a member of the science team for Mars Pathfinder and later a co-investigator for the Mars Odyssey and Mars Exploration Rovers projects.[45] The university also hosts Barry T. Rouse, an international award-winning Distinguished Professor of Microbiology who has conducted multiple NIH-funded studies on the herpes simplex virus (HSV) and who is a leading researcher in his field.[46] UT's agricultural research programs are considered to be among the most accomplished in the nation, and the Institute for a Secure and Sustainable Environment is home to the East Tennessee Clean Fuels Initiative, recognized by the United States Department of Energy as the "best local clean fuels program in America".[47]

Oak Ridge National Laboratory

The major hub of research at the University of Tennessee is Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), one of the largest government laboratories in the United States. ORNL is a major center of civilian and governmental research[48] and features two of the world's most powerful supercomputers.

SECU: the SEC Academic Initiative

The University of Tennessee is a member of the SEC Academic Consortium, now called the SECU, a collaborative endeavor designed to promote research, scholarship and achievement amongst the member universities in the Southeastern Conference.[49][50]

Howard H. Baker Jr. Center for Public Policy

The Howard H. Baker, Jr. Center for Public Policy regularly holds events relative to the center's three major areas of focus which are Energy & Environment, Global Security, and Leadership & Government. According to the center's website, its missions is "to provide policy makers, citizens, scholars and students with the information and skills necessary to work effectively within our political system and to educate our local, state, national and global communities". The center is housed in a 51,000-square-foot (4,700 m2), three-story domed building, which is also a gateway to the University of Tennessee campus and houses the Modern Political Archives (MPA), Chancellor's Honors Program and the Masters of Public Policy and Administration. The building also includes classrooms on the 2nd floor, MPA Research Room, Howard Baker Reading Room and Toyota Auditorium. Howard H. Baker Jr. Center for Public Policy host The Institute for Nuclear Security, which brings the complete capabilities of the university community to bear on one of the most challenging issues of our time—nuclear security. Starting from 2015 the Institute has been publishing the International Journal of Nuclear Security that aims to share and promote research and best practices in all areas of nuclear security. It provides an open-access, multi-disciplinary forum for scholarship and discussion. The journal encourages diversity in theoretical foundations, research methods, and approaches, asking contributors to analyze and include implications for policy and practice.[51]

Tennesseans and War Oral History Project

From August 29, 1984, to November 22, 2011, the University of Tennessee conducted the Tennesseans and War Oral History Project. The purpose of the project was to "uniquely capture the experiences and memories of veterans, including their lives before combat, motivations to enlist, personal experiences during the war, and their experiences readjusting to civilian life after".[52] The collection comprises seventy-eight interviews. All but twenty-two of the interviews have both audio recordings and a transcript of the interview. The twenty-two without audio have either a transcript of the interview or documents relating to the veteran/interviewee.

Other activities

In 2013, the University of Tennessee participated in the SEC Symposium in Atlanta which was organized and led by the University of Georgia and the UGA Bioenergy Systems Research Institute. The topic of the Symposium was titled, the "Impact of the Southeast in the World's Renewable Energy Future."[53]

Agricultural Campus

Through 21 departments, the Ag campus offers 11 undergraduate majors, 13 undergrad minors, 14 graduate programs, and veterinary medicine majors. The ag campus supports academics, research and community outreach.[54] The University of Tennessee Anthropological Research Facility, nicknamed the "Body Farm", is located near the University of Tennessee Medical Center on Alcoa Highway (US 129). Founded by William M. Bass in 1972, the Body Farm endeavors to increase anthropological and forensic knowledge specifically related to the decomposition of the human body and is one of the leading centers for such research in the United States.[55]

Cherokee Research Campus

On March 16, 2009, the university broke ground on a 188-acre (76 ha) campus in downtown Knoxville that will be devoted to nanotechnology, neutron science, materials science, energy, climate studies, environmental science, and biomedical science.[56]

Campus master plan

The university has implemented a 25-year (2001–2026) campus master plan that will facilitate a sweeping overhaul of campus design.[57] The plan is designed to make the campus more pedestrian-friendly by establishing large areas of open green space and relegating parking facilities to the periphery of the campus, and to increase the aesthetic appeal of the school by establishing uniform building design codes and by physically remodeling, restoring, and expanding existing academic, athletic, and housing facilities. Centrally located, iconic Ayres Hall underwent a massive upgrade as part of Phase 1 of the project, with work completed in 2011. The new Student Union has seen Phase 1 completion and is currently undergoing Phase 2, along with substantial new facilities for science, the performing arts, and athletics. An expected 3,000 new parking spaces will be developed along with improved mass transit and walking spaces. The plan calls for the removal of many of the roads that bisect the campus, along with the development of two new quads, one each on the main and agricultural campuses. Restoration and renovations of existing campus buildings are expected to be conducted in concert with historical preservationists when appropriate, according to the 2001 Master Plan document.[57]

Space Institute

The University of Tennessee Space Institute, located in Tullahoma, TN, is an extension of the Knoxville campus supporting research and graduate studies in aerospace engineering and related fields. The Space Institute is home to various supersonic wind tunnels used by the Department of Mechanical, Aerospace, and Biomedical Engineering. This includes Mach 2, Mach 2.3, and Mach 4 facilities. A Mach 7 wind tunnel is also being constructed to support hypersonic flight research at the University of Tennessee. The Space Institute is also home to the Center of Laser Applications (CLA), a state center of excellence.

Student life

Student body

| Race and ethnicity[58] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 76.7% | ||

| Black | 4.2% | ||

| Hispanic | 5.9% | ||

| Other[lower-alpha 1] | 5.9% | ||

| Asian | 3.5% | ||

| Foreign national | 3.6% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[lower-alpha 2] | 24% | ||

| Affluent[lower-alpha 3] | 76% | ||

In Fall 2023, the university enrolled 28,883 undergraduate and 7,421 graduate and professional students; 54.6% of students are female, 45.4% are male.[4] UT hosts students from all 50 U.S. states and over 90 foreign countries. 22,922 students come from Tennessee, and the next three most popular U.S. states are Georgia, Virginia, and North Carolina. The top three home countries of international students are China, India, and Bangladesh.[59]

Activities

- International House

- The International House is a popular gathering place for visiting international students and delegations and University of Tennessee students who have previously or are currently interested in studying abroad through the Programs Abroad Office. A full kitchen, meeting rooms, and a library provide support for frequent cultural events ranging from salsa dance lessons and nation-themed culture nights to Peace Corps interest meetings.[60]

- Black Cultural Center

- The Frieson Black Cultural Center, or BCC, houses the Office of Minority Student Affairs and offers a student computer lab, free Spanish tutoring, and a textbook loan service for economically disadvantaged students. There is a small but well-stocked library featuring numerous works examining religious and minority issues, and the facility offers free use of its meeting rooms to campus organizations and their affiliates.[61]

- Pride Center

- Located in the new Student Union, the Pride Center opened in 2010. It aims to create a shared space for the LGBT community at the university. In 2016 Tennessee State Legislature called for an investigation into the Pride Center because of the way faculty used pronouns, resulting in the Pride Center losing its official status and center director Donna Braquet being fired from her position, though she remains a professor at the university. The center regained its official status in 2019.[62]

- Campus Events Board

- The Campus Events Board (CEB) is a student organization with nearly two hundred members that runs the majority of campus events, activities, and programs for the student body. CEB hosts around a hundred events per year and is consistently ranked as one of the best collegiate programming organizations in the nation. Examples include, lectures, concerts, raves, movies, art exhibitions, and dance performances. CEB also runs Culture Week.

Organizations

The University of Tennessee has over 450 registered student organizations. These groups cater to a variety of interests and provide options for those interested in service, sports, arts, social activities, government, politics, cultural issues, and Greek societies.[63]

The university operates two radio stations: student-run The Rock (formerly the Torch)[64] (WUTK-FM 90.3 MHz) and National Public Radio affiliate WUOT-FM 91.9 MHz. The university's first radio station was on the AM frequency 850 kHz, a donation from Knoxville radio station WIVK-AM/FM. The Phoenix, a literary art magazine, is published in the fall and spring semesters and showcases student artistic creativity.

- The Volunteer Channel

The Volunteer Channel (TVC) is the university's student run television station. TVC reaches nearly 7,000 UT students in residence halls and 100,000 residents in surrounding counties on Comcast Digital Channel 194.[65]

The Daily Beacon

The Daily Beacon is the editorially independent student newspaper of UT's campus. It began in 1906 as The Orange & White and became a staple on the campus landscape, publishing for 61 years. The Daily Beacon was established as its successor in 1965, taking over in spring 1967. It printed 10,000 daily copies weekly, one of the few daily collegiate newspapers in the United States, prior to moving predominantly online.[66] It now distributes 2,100 copies per week, releasing on Wednesdays, and produces daily online content about the campus and the surrounding area.[67]

Greek institutions

The University of Tennessee hosts 22 sororities and 32 fraternities. Approximately 20% of undergraduate men and 30% of undergraduate women are active in UT's Greek system.[68]

Athletics

Tennessee competes in the Southeastern Conference's (SEC) Eastern Division, along with Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, South Carolina, and Vanderbilt. The only UT team that does not compete in the SEC is the women's rowing program, which competes as a single-sport member of the Big 12 Conference.

The Tennessee Lady Volunteers basketball team has won eight NCAA Division I titles (1987, 1989, 1991, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2007, 2008); only Connecticut, with eleven titles, has more championships. They are currently led by Kellie Harper. She succeeded Holly Warlick, who succeeded Pat Summitt, the all-time winningest basketball coach in NCAA history. Summitt's 1,000th victory occurred on February 5, 2009, and she boasts a 100 percent graduation rate for all players who finish their career at UT. Women's basketball rivals for Tennessee within the conference include Georgia, Vanderbilt, and LSU.

UT's best-known athletic facility by far is Neyland Stadium, home to the football team, which seats 101,915 people and is one of the country's largest facilities of its type.

In August 2014, University of Tennessee students were given the opportunity to vote for a name for the Neyland Stadium student section. The name "Rocky Top Rowdies" was selected over "General's Quarters", "Smokey's Howl", "Vol Army", and "Big Orange Crew."[69]

On November 10, 2014, as part of a university-wide branding overhaul, the UT athletic department announced that starting with the 2015–16 school year, all UT women's teams except for basketball would drop "Lady" from their nickname and become simply "Volunteers". The rebranding will coincide with UT's switch from Adidas to Nike as its uniform supplier.[70]

Club sports

The university also offers a number of recreational sports, many offering intercollegiate play. Sports include lacrosse, rugby, soccer, wrestling, hockey, running, crew, golf, ballroom dance, and paintball.[71] Teams often join intercollegiate conferences, such as the South Eastern Collegiate Hockey Conference, or play Southeastern Conference and in other rivals on a regular basis.

Colors

Charles Moore, president of the university's athletic association, chose orange and white for the school colors on April 12, 1889. His inspiration is said to have come from orange and white daisies which grew on the Hill. To this day there are still orange and white flowers grown outside the University Center. Although students confirmed the colors at a special meeting in 1892, dissatisfaction caused the colors to be dropped. No other acceptable colors could be agreed on, however, and the original colors were reinstated a day later. The University of Tennessee's official colors are UT Orange (Pantone 151), White, and Smokey Gray (Pantone 426).[72]

Pride of the Southland Band

The Pride of the Southland Band (or simply The Pride) is UT's marching band. As one of the oldest institutions at the university, the band partakes in many of the gameday traditions. At every home game, the Pride performs the "March to the Stadium" which includes a parade sequence and climaxes when the band stops at the bottom of The Hill and performs the "Salute to the Hill", an homage to the history and legacy of the university. The band is known for its pregame show at the beginning of every home game, which ends with the football team running onto the field through the "Opening of the T".

Mascot

Nickname

Tennessee is known as the "Volunteer State" for the large number of Tennesseans who volunteered for duty in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, and the American Civil War. A UT athletic team was dubbed the Volunteers for the first time in 1902 by the Atlanta Constitution following a football game against the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets, although the Knoxville Journal and Tribune did not use the name until 1905. By the fall of 1905 both the Journal and the then-Sentinel were using the nickname.[73]

The Rock

Unearthed in the 1960s, the Rock probably soon thereafter became a "canvas" for student messages. For years the university sandblasted away the messages but eventually deferred to students' artistic endeavors. The Daily Beacon has editorialized: "Originally a smaller rock, the Rock has grown in prestige and size while thousands of coats of paint have been thrown on its jagged face. Really, its function is as an open forum for students."[74]

Notable people

.jpg.webp) Peyton Manning, Hall of Fame NFL quarterback

Peyton Manning, Hall of Fame NFL quarterback Dixie Carter, actress

Dixie Carter, actress.jpg.webp) Candace Parker, professional women's basketball player

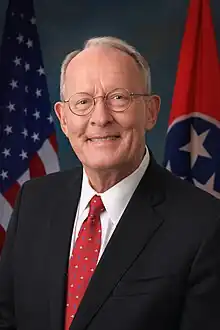

Candace Parker, professional women's basketball player Lamar Alexander, former US Senator

Lamar Alexander, former US Senator Scott Kelly, astronaut

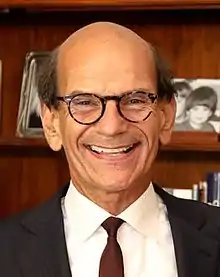

Scott Kelly, astronaut Paul Finebaum, sports author and television and radio personality

Paul Finebaum, sports author and television and radio personality.jpg.webp) Jason Witten, NFL tight end

Jason Witten, NFL tight end.jpg.webp) Bob Corker, former U.S. Senator

Bob Corker, former U.S. Senator.jpg.webp) Arian Foster, NFL running back

Arian Foster, NFL running back Kurt Vonnegut, author

Kurt Vonnegut, author Jim Justice, Governor of West Virginia

Jim Justice, Governor of West Virginia Heath Shuler, former NFL quarterback and U.S. Congressman

Heath Shuler, former NFL quarterback and U.S. Congressman Todd Helton, MLB first baseman

Todd Helton, MLB first baseman Allen West, former Chair of the Texas Republican Party and former US Congressman

Allen West, former Chair of the Texas Republican Party and former US Congressman.jpg.webp) Alvin Kamara, NFL running back

Alvin Kamara, NFL running back Gene Wojciechowski, sportswriter for ESPN

Gene Wojciechowski, sportswriter for ESPN Bill Haslam, 49th Governor of Tennessee

Bill Haslam, 49th Governor of Tennessee

See also

Notes

- ↑ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ↑ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ↑ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

- ↑ As of June 30, 2020U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2020 Endowment Market Value and Change in Endowment Market Value from FY19 to FY20 (Report). National Association of College and University Business Officers and TIAA. February 19, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ↑ "Donde Plowman". Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- ↑ "About the Provost". Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 "Quick Facts". University of Tennessee Knoxville. 2017. Archived from the original on April 2, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- 1 2 3 "University of Tennessee, Knoxville Fact Book". Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ↑ "IPEDS-University of Tennessee, Knoxville".

- ↑ "Highbeam.com". Highbeam.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Graduateguide.com". Graduateguide.com. October 13, 2010. Archived from the original on August 20, 2010. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "UTM.edu". UTM.edu. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Color Palettes | Brand Guidelines". Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ↑ "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". carnegieclassifications.iu.edu. Center for Postsecondary Education. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ↑ "The University of Tennessee: The Trip to the Hill - Knoxville History Project". Knoxville History Project. August 20, 2015. Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved October 17, 2018.

- ↑ Neeley, Jack. Knoxville's Secret History. Knoxville: Scruffy City Publishing, 1995, pp. 81–83. Retrieved October 27, 2012

- ↑ "UTK.edu". UTK.edu. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Hutton, Robert (September 25, 2018). "Desegregation". University of Tennessee. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ↑ "Renaming of University of Tennessee". Archived from the original on December 1, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. Naval Administration in World War II". HyperWar Foundation. 2011. Archived from the original on January 12, 2012. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ↑ "UTK.edu". Chancellor.utk.edu. September 4, 2007. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "About the UT System". Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ↑ "Office of the President". Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ↑ "Office of the Chancellor". Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Chancellor's Cabinet". Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Board Confirms Chancellor Appointments, General Counsel Reorganization". University of Tennessee. December 15, 2016. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 16, 2016.

- ↑ Vellucci, Amy J. (May 2, 2018). "Davenport fired as UT's chancellor, will be retained as faculty at $439K annually". The Tennessean. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- ↑ "FY 2015 Revised Budget Document". Budget Documents. University of Tennessee: 31. 2015. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ↑ "FY 2009 Revised Budget Document". Budget Documents. University of Tennessee: 7. 2009. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ↑ First Heart Hospital patient and family thankful for new facility University of Tennessee Medical Center Archived July 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 3 4 "UTK Fall 2023 Admissions". UTK Officr of Admissions. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ↑ "U.S. News Best Colleges Rankings: University of Tennessee". U.S. News & World Report. 2017. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ↑ "UTK Common Data Set 2020-2021" (PDF). UTK Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "UTK Common Data Set 2019-2020" (PDF). UTK Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "UTK Common Data Set 2018-2019" (PDF). UTK Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "UTK Common Data Set 2017-2018" (PDF). UTK Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "UTK Common Data Set 2016-2017" (PDF). UTK Office of Institutional Research and Assessment. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Forbes America's Top Colleges List 2023". Forbes. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ↑ "Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education College Rankings 2022". The Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ↑ "2023-2024 Best National Universities". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 22, 2023.

- ↑ "2022 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ↑ "ShanghaiRanking's Academic Ranking of World Universities". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings 2024: Top global universities". Quacquarelli Symonds. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ↑ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ↑ "2022-23 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ↑ "University of Tennessee Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. Best Colleges. 2022. Retrieved February 26, 2022.

- ↑ Klingler, Mary; Salvemini, Chris (August 25, 2022). "UT ranks as most LGBTQIA+ unfriendly university in national survey". 10 News WBLR.

- ↑ "UTK.edu". Web.eps.utk.edu. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ UTK.edu Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "UTK.edu". UTK.edu. September 11, 2006. Archived from the original on August 6, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Leadership-class Computing for Science" (PDF). ORNL Review. 37 (2). 2004. ISSN 0048-1262. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 30, 2005. Retrieved November 23, 2005.

- ↑ "SECU". SEC. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ↑ "SECU: The Academic Initiative of the SEC". SEC Digital Network. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ↑ "About This Journal | International Journal of Nuclear Security - Every link must hold. | University of Tennessee, Knoxville". trace.tennessee.edu. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved April 12, 2019.

- 1 2 "World War II Records | Tennesseans and War". October 14, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- ↑ Hastings, Terry (February 6, 2013). "SEC Symposium to address role of Southeast in renewable energy". Uga Today. University of Georgia. Archived from the original on February 12, 2013. Retrieved February 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Institute of Agriculture | UTIA". utia.tennessee.edu. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ↑ "Author Interview with Jefferson Bass". HarperCollins.com. Archived from the original on January 29, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- ↑ "Tennessee.edu". Tennessee.edu. Archived from the original on May 12, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- 1 2 "Facilities Master Plan". University of Tennessee. Archived from the original on May 14, 2009. Retrieved April 13, 2009.

- ↑ "College Scorecard: University of Tennessee-Knoxville". United States Department of Education. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ↑ "Top 10 Enrollment Feeders" (PDF). Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ↑ "International House". University of Tennessee - Knoxville. Archived from the original on December 4, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Black Cultural Center". University of Tennessee - Knoxville. Archived from the original on March 1, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ↑ Szymanowska, Gabriela (January 20, 2021). "Looking back at the history of the Pride Center". UT Daily Beacon. Retrieved August 28, 2021.

- ↑ "Student Organizations Resource Page". UTK.edu. Archived from the original on September 21, 2009. Retrieved September 21, 2009.

- ↑ "90.3 The Rock". WUTKradio.com. Archived from the original on December 14, 2005. Retrieved November 23, 2005.

- ↑ "The Volunteer Channel". www.volchannel.com. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014.

- ↑ "utdailybeacon.com - The editorially independent student newspaper at the University of Tennessee, since 1906". The Daily Beacon. Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ↑ "About Us". UTDailyBeacon.com. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ↑ "University of Tennessee, Knoxville Student Life". usnews.com. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

- ↑ "Student section named 'Rocky Top Rowdies'". WBIR.com. Archived from the original on September 18, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ↑ "One Tennessee: Branding Restructure" (Press release). University of Tennessee Athletics. November 10, 2014. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ↑ "UT Knoxville | RecSports". Recsports.utk.edu. Archived from the original on June 20, 2012. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ↑ "Our Primary Color". UTK.edu. UTK Office of Communications & Marketing. Archived from the original on September 12, 2013. Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ↑ "University of Tennessee Traditions: Volunteer Nickname". UTK.edu. Archived from the original on September 6, 2006. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- ↑ "University of Tennessee Traditions: The Rock". UTK.edu. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

External links

- Official website

- University of Tennessee Athletics website

- . . 1914.

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

_logo.svg.png.webp)