| "Ulla! min Ulla! säj får jag dig bjuda" | |

|---|---|

| Art song | |

Sheet music | |

| English | Ulla! my Ulla! say, may I thee offer |

| Written | 1790 |

| Text | poem by Carl Michael Bellman |

| Language | Swedish |

| Melody | Unknown origin, probably Bellman himself |

| Dedication | Mr Assessor Lundström |

| Published | 1790 in Fredman's Epistles |

| Scoring | voice and cittern |

Ulla! min Ulla! säj, får jag dig bjuda (Ulla! my Ulla! say, may I thee offer), is one of the Swedish poet and performer Carl Michael Bellman's best-known and best-loved songs,[1] from his 1790 collection, Fredman's Epistles, where it is No. 71. A pastorale, it depicts the Rococo muse Ulla Winblad, as the narrator offers her "reddest strawberries in milk and wine" in the Djurgården countryside north of Stockholm.

The epistle is a serenade, subtitled "Till Ulla i fönstret på Fiskartorpet middagstiden en sommardag. Pastoral dedicerad till Herr Assessor Lundström" (To Ulla in the window in Fiskartorpet at lunchtime one summer's day. Pastorale dedicated to Mr Assessor Lundström). It has been described as the apogee of the bellmansk, and a breezy evocation of Stockholm's Djurgården park in summertime. The serenade form was popular at the time, as seen in Mozart's opera Don Giovanni; Bellman has shifted the setting from evening to midday. In each verse, Fredman speaks to Ulla, describing his love through delicious food and drink; in the refrain, he softly encourages her to admire nature all around, and she replies with a few meditative words. The erotic charge steadily increases from one verse to the next, complete in the last verse with the energy of a horse.

Context

.jpg.webp)

Carl Michael Bellman is a central figure in the Swedish ballad tradition and a powerful influence in Swedish music, known for his 1790 Fredman's Epistles and his 1791 Fredman's Songs.[2] A solo entertainer, he played the cittern, accompanying himself as he performed his songs at the royal court.[3][4][5]

Jean Fredman (1712 or 1713–1767) was a real watchmaker of Bellman's Stockholm. The fictional Fredman, alive after 1767, but without employment, is the supposed narrator in Bellman's epistles and songs.[6] The epistles, written and performed in different styles, from drinking songs and laments to pastorales, paint a complex picture of the life of the city during the 18th century. A frequent theme is the demimonde, with Fredman's cheerfully drunk Order of Bacchus,[7] a loose company of ragged men who favour strong drink and prostitutes. At the same time as depicting this realist side of life, Bellman creates a rococo picture, full of classical allusion, following the French post-Baroque poets. The women, including the beautiful Ulla Winblad, are "nymphs", while Neptune's festive troop of followers and sea-creatures sport in Stockholm's waters.[8] The juxtaposition of elegant and low life is humorous, sometimes burlesque, but always graceful and sympathetic.[3][9] The songs are "most ingeniously" set to their music, which is nearly always borrowed and skilfully adapted.[10]

Song

Music and verse form

The song has three verses, each of 8 lines, with a chorus of 10 lines. The verses have the alternating rhyming pattern ABAB-CDCD.[2] The Assessor Lundström of the dedication was a friend of Bellman's and a stock character in the Epistles.[11]

The song is in 2

4 time, marked Allegro ma non troppo. The much-loved[12] melody, unlike nearly all the rest of the tunes used in the Epistles, but like those of the other Djurgården pastorales, cannot be traced beyond Bellman himself and may thus be of his own composition. It is "spaciously Mozartian", with da capos at the end of each verse creating yet more space, before a sudden switch to a minor key for the chorus.[11] Bellman's song about Haga, "Porten med blommor ett Tempel bebådar" ("The gate with flowers heralds a temple") is set to the same tune.[13][14][12]

Lyrics

The song is dated 1790, the year of publication, making this one of the last epistles to be written. It is dedicated to the assessor and member of Par Bricole, Carl Jacob Lundström, who helped find enough subscribers to finance the publication of Fredman's Epistles. It is possible that the late epistles, including nos. 80 and 82, were inspired by time spent with Helena Quiding at her summerhouse, Heleneberg, near Fiskartorpet.[15]

The song imagines the Fredman/Bellman narrator, seated on horseback outside Ulla Winblad's window at Fiskartorpet on a fine summer's day. Thirsty in the heat, he invites the heroine to come and eat with him, promising "reddest strawberries in milk and wine". As pastorally, but in Paul Britten Austin's view less plausibly for anyone who liked drinking as much as Fredman, he suggests "a tureen of water from the spring". The bells of Stockholm can be heard in the distance, as calèches and coaches roll into the yard.[11] The Epistle ends with a cheerful Skål! (Cheers!), as the poet settles "down beside the gate, in the warmest rye" with Ulla, to the "Isn't this heavenly" of the refrain. Where the stanzas are voiced by Fredman, the refrain consists of Fredman's questions and Ulla's brief but ecstatic answers.[2][12]

| Carl Michael Bellman, 1790[16] | Charles Wharton Stork, 1917[17] | Hendrik Willem van Loon, 1939[18] | Paul Britten Austin, 1977[19] |

|---|---|---|---|

Ulla! min Ulla! säj får jag dig bjuda |

Ulla, mine Ulla, to thee may I proffer |

Ulla, my Ulla, say, do you like my offer |

Ulla, my Ulla, what sayst to my offer? |

Reception

1 Haga park (S. 64) – 2 Brunnsviken – 3 Första Torpet (Ep. 80) – 4 Kungsholmen – 5 Hessingen (Ep. 48) – 6 Lake Mälaren (Ep. 48) – 7 Södermalm – 8 Urvädersgränd – 9 Lokatten tavern (Ep. 11, Ep. 59, Ep. 77), Bruna Dörren tavern (Ep. 24, Ep. 38) – 10 Gamla stan (Ep. 5, Ep. 9, Ep. 23, Ep. 28, Ep. 79) – 11 Skeppsbron Quay (Ep. 33) – 12 Årsta Castle – 13 Djurgården Park – (Ep. 25, Ep. 51, Ep. 82) – 14 Gröna Lund (Ep. 12, Ep. 62) – 15 Bellman's birthplace – 16 Fiskartorpet (Ep. 71) – 17 Lilla Sjötullen (Bellmanmuseet) (Ep. 48) – 18 Bensvarvars tavern (Ep. 40) 19 Rostock tavern (Ep. 45)

Bellman's biographer, Paul Britten Austin, describes the song as "the apogee, perhaps, of all that is typically bellmansk.. the ever-famous Ulla, min Ulla, a breezy evocation of Djurgården on a summer's day."[11]

The scholar of literature Lars Lönnroth sets "Ulla! min Ulla!" among Bellman's "great pastorals", alongside Fredman's Epistles no. 80, "Liksom en herdinna", and no. 82, "Vila vid denna källa". These have, he notes, been called the Djurgården pastorales, for their geographical setting, though they are not the only epistles to be set in that park. Lönnroth comments that they owe something of their tone and lexicon to "the elegant French-influenced classicism which was praised by contemporary Gustavian poets".[12] These epistles incorporate, in his view, an element of parody and anti-pastoral grotesque, but this is dominated by a strong genuine pleasure in "the beauty of summer nature and the delights of country life".[12]

Lönnroth writes that the song is a serenade, as Bellman's dedication has it, "to Ulla in the window at Fiskartorpet".[12] The form was popular at the time in works such as Mozart's opera Don Giovanni, deriving from Spanish, where a serenade (sera: "evening") meant a profession of love set to the strings of a guitar outside the beloved's window of an evening. In Bellman's hands, the setting is shifted to midday in a Swedish summer. Fredman can, he writes, be supposed to have spent the night with Ulla after an evening of celebration; now he sits on his horse outside her window and sings to her. In the first half of each verse, in the major key, he speaks straight to Ulla, offering his love in the form of delicious food and drink; in the second half, the refrain, in the minor key, he encourages her more softly to admire nature all around, and she replies with a meditative word or two: "Heavenly!"; "Oh yes!".[12] There is, furthermore, a definite erotic charge, increasing in each of the three verses. In the first verse, the house's doors are suggestively blown open by the wind, while in the last verse, the neighing, stamping, galloping horse appears as a sexual metaphor alongside Fredman's expressed passion.[12]

Charles Wharton Stork's 1917 anthology calls Bellman a "master of improvisation"[lower-alpha 2][21] who "reconciles the opposing elements of style and substance, of form and fire ... we witness the life of Stockholm [including] various idyllic excursions [like Epistle 71] into the neighboring parks and villages. The little world lives and we live in it."[22] Hendrik Willem van Loon's 1939 introduction and sampler names Bellman "the last of the Troubadours, the man who was able to pour all of life into his songs".[23]

Epistle 71 has been recorded by the stage actor Mikael Samuelsson (Sjunger Fredmans Epistlar, Polydor, 1990),[24] the singers and by the noted Bellman interpreters Cornelis Vreeswijk, Evert Taube[25] and Peter Ekberg Pelz.[26] The Epistle has been translated into English by Eva Toller.[27]

Lithograph for Epistle 71 by Elis Chiewitz, 1827

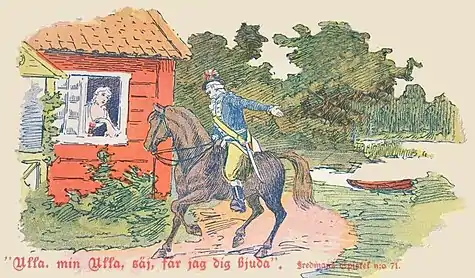

Lithograph for Epistle 71 by Elis Chiewitz, 1827 A serenade at Fiskartorpet:[12] Coloured postcard of "Ulla! min Ulla!", with Fredman on his horse, and Ulla at her window, 1903

A serenade at Fiskartorpet:[12] Coloured postcard of "Ulla! min Ulla!", with Fredman on his horse, and Ulla at her window, 1903

Notes

- ↑ Stork here uses "town" for torp, which means "cottage".

- ↑ He was echoing King Gustav III's "Il signor improvisatore".[20]

References

- ↑ "Information om Fredman i Bellmans epistlar". Stockholm Gamla Stan. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 Bellman 1790.

- 1 2 "Carl Michael Bellmans liv och verk. En minibiografi (The Life and Works of Carl Michael Bellman. A Short Biography)" (in Swedish). Bellman Society. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ↑ "Bellman in Mariefred". The Royal Palaces [of Sweden]. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ↑ Johnson, Anna (1989). "Stockholm in the Gustavian Era". In Zaslaw, Neal (ed.). The Classical Era: from the 1740s to the end of the 18th century. Macmillan. pp. 327–349. ISBN 978-0131369207.

- ↑ Britten Austin 1967, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Britten Austin 1967, p. 39.

- ↑ Britten Austin 1967, pp. 81–83, 108.

- ↑ Britten Austin 1967, pp. 71–72 "In a tissue of dramatic antitheses—furious realism and graceful elegance, details of low-life and mythological embellishments, emotional immediacy and ironic detachment, humour and melancholy—the poet presents what might be called a fragmentary chronicle of the seedy fringe of Stockholm life in the 'sixties.".

- ↑ Britten Austin 1967, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 4 Britten Austin 1967, pp. 155–156

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Lönnroth 2005, pp. 320–323.

- ↑ Massengale 1979, p. 200.

- ↑ Byström, Olof (1966). "Med Bellman Pa Haga Och Norra Djurgarden" (PDF). Stockholmskällan. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ↑ "N:o 71 (Kommentar tab)". Bellman.net (in Swedish). Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ Hassler & Dahl 1989, p. 165.

- ↑ Stork 1917, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Van Loon & Castagnetta 1939, pp. 67–70.

- ↑ Britten Austin 1977, p. 77.

- ↑ Kleveland & Ehrén, 1984. page 6.

- ↑ Stork 1917, p. xvii.

- ↑ Stork 1917, p. xix.

- ↑ Van Loon, 1939. page 6

- ↑ "Mikael Samuelson – Sjunger Fredmans Epistlar". Discogs. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ↑ "Evert Taube Sjunger Och Berättar Om Carl Michael Bellman". Discogs. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ Hassler & Dahl 1989, p. 284.

- ↑ Toller, Eva. "Glimmande nymf - Epistel Nr 71". Eva Toller. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

Sources

- Bellman, Carl Michael (1790). Fredmans epistlar. Stockholm: By Royal Privilege.

- Britten Austin, Paul (1967). The Life and Songs of Carl Michael Bellman: Genius of the Swedish Rococo. New York: Allhem, Malmö American-Scandinavian Foundation. ISBN 978-3-932759-00-0.

- Britten Austin, Paul (1977). Fredman's Epistles and Songs. Stockholm: Reuter and Reuter. OCLC 5059758.

- Hassler, Göran; Dahl, Peter (illus.) (1989). Bellman – en antologi [Bellman – an anthology]. En bok för alla. ISBN 91-7448-742-6. (contains the most popular Epistles and Songs, in Swedish, with sheet music)

- Kleveland, Åse; Ehrén, Svenolov (illus.) (1984). Fredmans epistlar & sånger [The songs and epistles of Fredman]. Stockholm: Informationsförlaget. ISBN 91-7736-059-1. (with facsimiles of sheet music from first editions in 1790, 1791)

- Lönnroth, Lars (2005). Ljuva karneval! : om Carl Michael Bellmans diktning [Lovely Carnival! : about Carl Michael Bellman's Verse]. Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag. ISBN 978-91-0-057245-7. OCLC 61881374.

- Massengale, James Rhea (1979). The Musical-Poetic Method of Carl Michael Bellman. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International. ISBN 91-554-0849-4.

- Stork, Charles Wharton (1917). Anthology of Swedish lyrics from 1750 to 1915. New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- Van Loon, Hendrik Willem; Castagnetta, Grace (1939). The Last of the Troubadours. New York: Simon and Schuster.