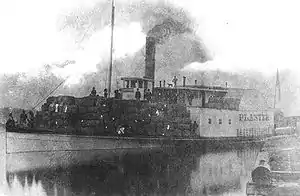

Steamer Planter loaded with 1,000 bales of cotton at Georgetown, South Carolina. Ca 1860–61 or 1866–76 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | USS Planter |

| Launched | 1860 |

| Acquired | 30 May 1862 |

| In service | 1862 |

| Fate | Transferred to the Union Army, circa August 1862; sank during a storm on March 26, 1876 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Steamer |

| Tonnage | 313 register[1] |

| Length | 147 ft (45 m) |

| Beam | 30 ft (9.1 m) |

| Draft | 3 ft 9 in (1.14 m) |

| Depth of hold | 7 ft 10 in (2.39 m) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Armament | 1 × long 32-pounder gun, 1 × short 24-pounder howitzer |

USS Planter was a steamer taken over by Robert Smalls, a Southern slave and ship's pilot who steered the ship past Confederate defenses and surrendered it to Union Navy forces on 13 May 1862 during the American Civil War. The episode is missing from Scharf's History of the Confederate States Navy, except for one sentence saying that Smalls "stole" the ship.[2]

For a short period, Planter served as a gunboat for the Union Navy. As the ship burned wood, which was scarce where the Navy was operating, the Navy turned the ship over to the Union Army for use at Fort Pulaski on the Georgia coast. In 1863 Smalls was appointed captain of Planter, the first black man to command a United States ship, and served in that position until 1866.

Service history

Planter was a sidewheel steamer built at Charleston, South Carolina, in 1860 that was used by the Confederacy as an armed dispatch boat and transport attached to the engineer department at Charleston, under Brigadier General Roswell Ripley, CSA.

At 04:00 on 13 May 1862, while her captain, C. J. Relyea, was absent on shore, Robert Smalls, a slave who was Planter's helmsman (the title "pilot" being reserved for white men trained in navigation of rivers,) quietly took the ship from the wharf, and with a Confederate flag flying, steamed past the successive Confederate forts. He saluted the installation as usual by blowing the steam whistle. As soon as the steamer was out of range of the last Confederate gun, Smalls hauled down the Confederate flag and hoisted a white one. Then he turned Planter over to the USS Onward of the Union blockading force. Besides Smalls, Planter carried 15 other slaves to freedom behind Union lines – seven crewmen, five women, and three children. In addition to the cargo of artillery and explosives, Smalls brought Flag officer Samuel Francis Du Pont valuable intelligence, including word that the Confederates had abandoned defensive positions on the Stono River.

The next day, Planter was sent to Flag Officer Du Pont at Port Royal Harbor, South Carolina, who later assigned Robert Smalls as Planter's pilot. At the time she was taken over by the Union, Planter was carrying four guns as cargo beside her usual armament. The United States Senate and House of Representatives passed a private bill on 30 May 1862, granting Robert Smalls and his African-American crew one half of the value of Planter and her cargo as prize money. At the very time of the seizure she had on board the armament for Fort Ripley. The Planter was taken by the government at a valuation of $9,000, one-half of which was paid to the captain and crew, the captain receiving one-third of one-half, or $1,500. However, $9,000 was a very low valuation for the Planter. The real value was around $67,000. The report of Montgomery Sicard, commander and inspector of ordnance, to Commodore Patterson, navy-yard commandant, shows that the cargo of the Planter, as raw material, was worth $3,043.05; that at antebellum prices it was worth $7,163.35, and at war prices $10,290.60.

Service in the Union Navy

Du Pont took Planter into the Union Navy and placed her under command of Acting Master Philemon Dickenson. On 30 May he ordered the side-wheeler to North Edisto, where Acting Master Lloyd Phoenix relieved Dickenson. Planter served the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron through the summer of 1862. On a joint expedition under Lieutenant Rhind, the USS Crusader and Planter carried troops to Simmons Bluff, Wadmelaw River, South Carolina, where they destroyed a Confederate encampment.

Planter transferred to the Union Army

The Southern steamer had been designed to use only wood as fuel, a scarce commodity for the Union blockaders off Charleston, South Carolina. In the fall of 1862, Du Pont ordered her transferred to the Union Army for service near Fort Pulaski on the coast of Georgia.[3]

Planter under fire

After his escape, Smalls served as a pilot for Union ships in the Charleston area. He was eventually assigned to serve aboard Planter again. On December 1, 1863, Planter was caught in a crossfire between Union and Confederate forces. The ship's commander, a Captain Nickerson, ordered him to surrender. Smalls refused, saying he feared her black crewmen would not be treated as prisoners of war and that they might be summarily killed.

Smalls took command and piloted the ship out of range of the Confederate guns. As a reward for his bravery, he was appointed captain of the Planter, becoming the first black man to command a United States ship.[4] Smalls served as captain until the army sold Planter in 1866 after the end of the war.[3]

After the war

On March 25, 1876, while trying to tow a grounded schooner, the Planter sprang a plank in the bow and began to take on water in the hold. The captain elected to beach the steamer and repair the plank, hoping to get off the beach with the next high tide. However, stormy seas battered the Planter as the tide rose and the ship was too badly damaged and had to be abandoned. Upon hearing of its loss, Robert Smalls was reported to have said that he felt as if he had lost a member of his family.[5]

In May 2014 the NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) reported that it believed it had found the Planter's wreck.[6]

References

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- ↑ "The steamer Planter" in The Search for Planter, p. 7.

- ↑ Scharf, J. Thomas (1894). History of the Confederate States Navy. From Its Organization to the Surrender of Its Last Vessel (2nd ed.). Albany, New York: J. McDonough. p. 88.

- 1 2 Howard Westwood, "Robert Smalls: Commander of the Planter", Civil War Times, 12 Mar 2006, History Net, accessed 10 Jan 2011

- ↑ Gerald S. Henig (2018-11-21). "The Unstoppable Mr. Smalls". Historynet.com.

- ↑ "NOAA Close to Finding Civil War-Era Steamer". 13 May 2014.

- ↑ "NOAA identifies probable location of iconic Civil War-era steamer". NOAA. 13 May 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2021.