| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | October 28, 1998 |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

| Employees | 15+ |

| Agency executive |

|

| Website | www |

The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) is a U.S. federal government commission created by the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) of 1998. USCIRF Commissioners are appointed by the President and the leadership of both political parties in the Senate and the House of Representatives. USCIRF's principal responsibilities are to review the facts and circumstances of violations of religious freedom internationally and to make policy recommendations to the President, the Secretary of State, and the Congress.

History

.pdf.jpg.webp)

USCIRF was authorized by the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998, which established:[1][2]

- An Office of International Religious Freedom in the United States Department of State, headed by an Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom

- A mandate that the State Department prepare Annual Reports on International Religious Freedom

- A requirement to name the most egregious religious freedom violators as Countries of Particular Concern (CPCs) and to take policy actions in response to all violations of religious freedom as a specific element of U.S. foreign policy programs, cultural exchanges, and international broadcasting.

- The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF)[3]

The legislation authorizing the USCIRF stated that the Commission would terminate on September 30, 2011, unless it was reauthorized or given a temporary extension. It was given several extensions by Congress, but would have expired at 5:00 pm on Friday, December 16, 2011, had it not been reauthorized for a seven-year term (until 2018), on the morning of the 16th. This happened after a new reauthorization bill passed both Houses containing two amendments were made to it that Senator Dick Durbin, D-IL (the Senate Majority Whip) had wanted as a condition of releasing a hold he had placed on the former version of the bill; he released it on December 13, after the revisions were made. They stipulate that there will be a two-year limit on terms for commissioners and that they will be under the same travel restrictions as employees of the Department of State.[4][5]

In 2016, the U.S. Congress passed and President Barack Obama signed the Frank R. Wolf International Religious Freedom Act, which amended IRFA in various ways, including adding a category of designation for non-state actors.[6]

Duties and responsibilities

USCIRF researches and monitors international religious freedom issues. The Commission is authorized to travel on fact-finding missions to other countries and hold public hearings.[2]

The Commission on International Religious Freedom issues an annual report that includes policy recommendations to the U.S. government based on the report's evaluation of the facts and circumstances of religious freedom violations worldwide.[7]

Commissioners

The International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 provides for the Commission to be composed of ten members:[8]

- Three appointed by the President

- Three appointed by the President pro tempore of the Senate, of which two of the members shall be appointed upon the recommendation of the leader in the Senate of the political party that is not the political party of the President, and of which one of the members shall be appointed upon the recommendation of the leader in the Senate of the other political party

- Three appointed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives, of which two of the members shall be appointed upon the recommendation of the leader in the House of the political party that is not the political party of the President, and of which one of the members shall be appointed upon the recommendation of the leader in the House of the other political party.

- The Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom, as a non-voting ex officio member

IRFA provides that "Members of the Commission shall be selected among distinguished individuals noted for their knowledge and experience in fields relevant to the issue of international religious freedom, including foreign affairs, direct experience abroad, human rights, and international law." Commissioners are not paid for their work on the Commission, however they are provided a travel budget and a 15–20 member staff. Appointments last for two years, and Commissioners are eligible for reappointment.

As of July 19, 2023,[9] the current Commissioners are:

| Commissioner | Appointed By | Term expires | Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abraham Cooper (Chair)[10] | Mitch McConnell | May 2024 | Associate Dean and Director of Global Social Action for the Simon Wiesenthal Center[11] |

| Frederick A. Davie (Vice Chair)[10] | Chuck Schumer | May 2024 | Senior Strategic Advisor to the President, Union Theological Seminary;[12] former member of the Advisory Council for the White House Office of Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships |

| David Curry | Kevin McCarthy | May 2024 | President and CEO of Global Christian Relief[13] |

| Susie Gelman | Joe Biden | May 2025 | Board Chair (2016–2023), Israel Policy Forum; former President of the Jewish Federation of Greater Washington; member of the Board of Governors of The Hebrew University; past President of the Goldman Environmental Foundation[14] |

| Mohamed Magid | Joe Biden | May 2024 | Executive Religious Director, All Dulles Area Muslim Society Center; Chairman, International Interfaith Peace Corps; Co-President, Religions for Peace; Co-Founder, Multi-faith Neighbors Network[15] |

| Stephen Schneck | Joe Biden | May 2024 | Retired Executive Director of the Franciscan Action Network; Former associate professor at The Catholic University of America; former Director of CUA's Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies; former member of the advisory council for the White House Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships[16] |

| Nury Turkel | Nancy Pelosi | May 2024 | Chairman of the Board, Uyghur Human Rights Project; former president, Uyghur American Association[17] |

| Eric Ueland | Mitch McConnell | May 2024 | Former acting Under Secretary of State for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights; former Director of the Office of U.S. Foreign Assistance Resources at the Department of States; former Trump White House advisor; former Capitol Hill staffer[18] |

| Frank Wolf | Kevin McCarthy | May 2024 | Former Member, U.S. House of Representatives (VA-10); Author of the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA); founder and former co-chair, Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission[19] |

The State Department's Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom, currently Rashad Hussain, serves as an ex officio, non-voting member of the Commission.[8]

Past Commissioners include Sharon Kleinbaum, Tom Reese, S.J., Khizr Khan, Tony Perkins, David Saperstein,[20] Preeta D. Bansal, Gayle Conelly Manchin (Chair),[21] Gary Bauer, John Hanford, Khaled Abou El Fadl, Charles J. Chaput, Michael K. Young, Firuz Kazemzadeh, Shirin R. Tahir-Kheli, John R. Bolton, Elliot Abrams, Felice D. Gaer, Azizah Y. al-Hibri, Leonard Leo, Richard Land,[22] Tenzin Dorjee (Chair),[23] and Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz.[24]

Designations

The International Religious Freedom Act requires the President, who has delegated this function to the Secretary of State, to designate as “countries of particular concern,” or CPCs, countries that commit systematic, ongoing, and egregious violations of religious freedom. Pursuant to IRFA, USCIRF recommends the countries that, in its view, meet the CPC threshold and should be so designated.[25]

In addition to recommending countries for CPC designation, USCIRF also recommends countries to be added to the State Department's Special Watch List (SWL). The SWL is for countries whose governments engage or tolerate in severe religious freedom violations, but do not rise to the CPC standard of “systematic, ongoing, and egregious.” Violations in SWL countries must meet two of those three criteria.[25]

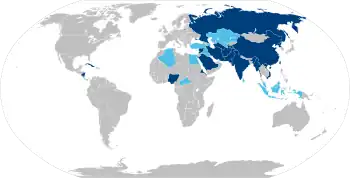

In its 2023 report, USCRIF recommended the following countries be designated as countries of particular concern: Afghanistan, China, Cuba, Eritrea, India, Iran, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Nigeria, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Vietnam. Additionally, USCIRF recommended that Algeria, Azerbaijan, the Central African Republic, Egypt, Indonesia, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Turkey, and Uzbekistan be included on the State Department's Special Watch List.[26]

India

USCIRF has repeatedly designated India as a country of particular concern or on the Special Watch List. These reports have drawn criticism from the Indian press. The Pioneer, in an editorial, termed it as "fiction", "biased", and "Surpassing Goebbels". It criticized USCIRF for projecting the massacre of 58 Hindu passengers as an accident. It also accused USCIRF of indirectly justifying murder of Swami Lakshamananda, a Hindu cleric and social activist.[27]

Christian leaders in Odisha defended India: Archbishop Raphael Cheenath stated that India remained of a secular character, the president of the Odisha Minority Forum that, despite a small hate campaign against minorities, the majority of society had been "cordial and supportive", and the Orissa Secular Front that, despite the 2002 and 2008 riots, India had a strong secular foundation.[28]

In the 2019 USCIRF report, the chairman Tenzin Dorjee disagreed with the commission's designation of India as a CPC citing having lived in India for 30 years as a religious refugee stating that "India is an open society with a robust democratic and judiciary system. India is a great civilization, and since ancient times she has been a country of multifaith, multilingual, and multicultural diversity."[29]

Several Indian-American Muslim, Sikh and Christian groups applauded the USCIRF for its 2021 report wherein it has recommended India be designated as a "country of particular concern (CPC)" for the alleged deterioration of religious freedom in the country.[30]

Egypt

Prior to the 2001 visit of the USCIRF to Egypt, some Coptic leaders in Egypt protested, viewing the visit as a form of American imperialism. For example, Mounir Azmi, a member of the Coptic Community Council, said that despite problems for Copts, the visit was a "vile campaign against Egypt" and would be unhelpful. Another critic called the visit "foreign intervention in our internal affairs".[31] In the event, the USCIRF was able to meet the Coptic Orthodox Pope Shenouda III and Mohammed Sayed Tantawi of Al-Azhar University, but others refused to meet the delegation. Hisham Kassem, chairman of the Egyptian Organization for Human Rights, felt that insisting on the rights of Christians in Egypt might antagonize Muslims and thus be counterproductive.[32]

Laos

The first-ever U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom, Robert Seiple, criticized the USCIRF's emphasis on the punishment of religious persecution over the promotion of religious freedom. In his view, the USCIRF was "only cursing the darkness". As an example, he highlighted the Commission's decision to designate Laos a Country of Particular Concern in 2002 despite the release of religious prisoners. He further stated, "that which was conceived in error and delivered in chaos has now been consigned to irrelevancy. Unless the Commission finds some candles soon, Congress ought to turn out the lights."[33]

The Commission responded that despite the releases, the Marxist, Pathet Lao government in Laos still had systemic impediments to religious freedom, such as laws allowing religious activities only with the consent of Pathet Lao government officials, and laws allowing the government to determine whether a religious community is in accord with its own teaching.[34]

Other non-governmental organizations (NGOs), religious freedom and human rights advocates, policy experts, and Members of Congress have defended the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom's research work, and various reports on the Pathet Lao government's increased and serious religious persecution in Laos, from Seiple's controversial criticism. They have pointed out potential conflicts of interest involving reported grant monies Seiple, or a non-profit organization connected to Seiple, reportedly received from officials at the U.S. Department of State to apparently seek to minimize grossly increased religious persecution and widespread human rights violations by the Lao government and the Lao People's Army.[35]

Central Asia

In 2007, Central Asia and foreign affairs experts S. Frederick Starr, Brenda Shaffer, and Svante Cornell accused USCIRF of championing the rights of groups that aspire to impose religious coercion on others in the name of religious freedom in the Central Asian states of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. USCIRF has castigated these countries for excessive and restrictions on religious freedom and repression of non-traditional religious groups, despite them having a strict separation of church and state, refusing to make Islam the state religion, and having a secular legal system.[36]

Tajikistan Foreign Ministry criticized the USCIRF report on March 13, 2020. Tajikistan called on the U.S. Department of State to refrain from publishing unverified and groundless information unrelated to the actual situation with the rule of law and respect of human rights in Tajikistan.[37]

Criticism

Accusations of Christian bias and other issues

A former policy analyst, Safiya Ghori-Ahmad, filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, alleging that she was fired because she was a Muslim and a member of an advocacy group, the Muslim Public Affairs Council. Current commissioners and some other religious freedom advocates deny the claims of bias. The commission has also been accused of in-fighting and ineffectiveness.[38]

Jemera Rone of Human Rights Watch said about the report: "I think the legislative history of this Act will probably reflect that there was a great deal of interest in protecting the rights of Christians ... So I think that the burden is probably on the US government to show that in this Act they're not engaging in crusading or proselytization on behalf of the Christian religion."[39]

In a 2009 study of the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998, the Institute of Global Engagement stated that the United States' international religious freedom policy was problematic in that it "has focused more on rhetorical denunciations of persecutors and releasing religious prisoners than on facilitating the political and cultural institutions necessary to religious freedom," and had therefore been ineffective. It further stated that USIRF policy was often perceived as an attack on religion, cultural imperialism, or a front for American missionaries. The report recommended that there be more attention to religious freedom in U.S. diplomacy and foreign policy in general and that the USCIRF devote more attention to monitoring the integration of religious freedom issues into foreign policy.[40]

In 2018, the appointment of Tony Perkins as a commissioner received criticism.[41] The organizations such as GLAAD, Hindu American Foundation, atheist and humanist groups, and others questioned the credibility of Perkins, citing his stance against non-Christians and LGBTQ people.[42] The Southern Poverty Law Center also chastised Perkins for far-right Christian views, his anti-LGBT views, his associations with the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups, terming his evangelical organization, the Family Research Council, a "hate group".[43]

References

Citations

- ↑ GPO Public Law 105 - 292 - International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 Page accessed June 3, 2016

- 1 2 GPO International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 text Page accessed June 3, 2016

- ↑ "Authorizing Legislation & Amendments". United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. February 2008.

- ↑ Authorizing Legislation & Amendments, United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. Accessed on-line June 4, 2010.

- ↑ "US religious freedom commission reauthorized at last minute". Catholic News Agency.

- ↑ "The International Religious Freedom Act: A Primer". Lawfare. January 10, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- ↑ "H.R. 2431" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- 1 2 Cozad, Laurie (2005). "The United States' Imposition of Religious Freedom: The International Religious Freedom Act and India". India Review. 4 (1): 59–83. doi:10.1080/14736480590919617. S2CID 153774347.

- ↑ "Commissioners: Advocates for Religious Freedom | USCIRF". www.uscirf.gov. November 16, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- 1 2 "Abraham Cooper Elected as Chair of Bipartisan U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, Frederick A. Davie as Vice Chair". United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ↑ "Abraham Cooper". Abraham Cooper | USCIRF. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Frederick A. Davie | USCIRF". www.uscirf.gov. November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ↑ "David Curry". David Curry | USCIRF. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Susie Gelman". U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ↑ "Mohamad Magid". USCIRF. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ↑ "Stephen Schneck". Stephen Schneck | USCIRF. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Nury Turkel | USCIRF". www.uscirf.gov. November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ↑ "Eric Ueland". Eric Ueland | USCRIF. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Frank Wolf". Frank Wolf | USCIRF. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ↑ "US Senate approves rabbi as freedom of faith envoy", The Times of Israel, December 15, 2014. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ↑ "USCIRF Congratulates Outgoing Chair, Gayle Manchin, Welcomes New Chair, Anurima Bhargava | USCIRF". www.uscirf.gov. November 16, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ↑ "Former Commissioners". United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. April 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Dr. Tenzin Dorjee, Commissioner". United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. December 8, 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Kristina Arriaga de Bucholz, Commissioner". USCIRF. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- 1 2 "Frequently Asked Questions". United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "2023 Recommendations". United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. Retrieved July 14, 2023.

- ↑ Sandeep B. (August 19, 2009). "Surpassing Goebbels". The Pioneer. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- ↑ "Orissa: Christian leaders disagree with US panel's report". Rediff. August 14, 2009. Retrieved October 8, 2010. Babu Thomas (August 17, 2009). "Orissa Christians reject USCIRF report, defends 'secular' India". Christianity Today. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- ↑ United States Commission on International Religious Freedom 2019 Annual Report (PDF). 2019. p. 181. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ↑ "Muslim, Sikh, Christian groups applaud USCIRF for its religious freedom report on India". April 23, 2021.

- ↑ "US commission faces closed doors" Archived November 27, 2003, at the Wayback Machine, Omayma Abdel-Latif, Al-Ahram Weekly, March 22–28, 2001, #526. Accessed on line June 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Egypt: Religious Freedom Delegation Gets Cold Shoulder", Kees Hulsman, Christianity Today, May 21, 2001. Accessed on line June 12, 2010.

- ↑ "Speaking Out: The USCIRF Is Only Cursing the Darkness". Christianity Today. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- ↑ "Speaking Out: USCIRF's Concern Is To Help All Religious Freedom Victims". Christianity Today. November 1, 2002. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ↑ Smith, Philip, Center for Public Policy Analysis (or Centre for Public Policy Analysis), (10 December 2004), Washington, D.C.

- ↑ S. Frederick Starr, Brenda Shaffer, and Svante Cornell (August 24, 2017). "How the U.S. Promotes Extremism in the Name of Religious Freedom". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Statement by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Tajikistan on the US Human Rights Report

- ↑ Boorstein, Michelle (February 17, 2010). "Agency that monitors religious freedom abroad accused of bias". The Washington Post. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ↑ Hackett, Rosalind; Silk, Mark; Hoover, Dennis (2000). "Religious Persecution as a U.S. Policy Issue" (PDF). Center for the Study of Religion in Public Life. Harford: 56. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ↑ Thomas F. Farr and Dennis R. Hoover. "The Future of U.S. International Religious Freedom Policy (Special Report)". Archived from the original on December 14, 2009. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- ↑ "Longtime gay-rights opponent Tony Perkins named to U.S. religious freedom panel". NBC. May 17, 2018.

- ↑ "Appointment of Far-Right Evangelist Tony Perkins Strains Credibility of USCIRF". Hindu American Foundation. May 16, 2018. Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

- ↑ "Tony Perkins". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved January 24, 2019.

Further reading

- Stahnke, Tad. A Paradox of Independence: The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom. The Review of Faith and International Affairs 6.2 (2008). Print.

- Farr, Thomas, Richard W. Garnett, Jeremy Gunn, and William Saunders (2009). "Religious Liberties: the International Religious Freedom Act". Houston Journal of International Law. 31 (3): 469–514.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Library resources about United States Commission on International Religious Freedom |

![]() Media related to United States Commission on International Religious Freedom at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to United States Commission on International Religious Freedom at Wikimedia Commons