| Cuju | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chinese ladies playing cuju, by Ming dynasty painter Du Jin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 蹴鞠 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "kick ball" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cuju or Ts'u-chü (蹴鞠) is an ancient Chinese ball game that is the earliest known recorded game similar to football.[1] It is a competitive game that involves both teams trying to kick a ball through an opening into a central hoop without the use of hands whilst ensuring the ball does not touch the ground[2]. This is similar to how hackey-sack is played today. Descriptions of the game date back to the Han dynasty, with a Chinese military work from the 3rd–2nd century BC describing it as an exercise.[1][3] It was also played in other Asian countries like Korea, Japan and Vietnam.[4]

History

The first mention of cuju in a historical text is in the Warring States era Zhan Guo Ce, in the section describing the state of Qi.[5] It is also described in Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian (under the Biography of Su Qin), written during the Han dynasty.[6][7] A competitive form of cuju was used as fitness training for military cavaliers, while other forms were played for entertainment in wealthy cities like Linzi.[6]

During the Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220), the popularity of cuju spread from the army to the royal courts and upper classes.[8] It is said that the Han emperor Wu Di enjoyed the sport. At the same time, cuju games were standardized and rules were established. Cuju matches were often held inside the imperial palace. A type of court called ju chang (鞠場) was built especially for cuju matches, which had six crescent-shaped goal posts at each end.

The sport was improved during the Tang dynasty (618–907).[9] First of all, the feather-stuffed ball was replaced by an air-filled ball with a two-layered hull. Also, two different types of goal posts emerged: One was made by setting up posts with a net between them and the other consisted of just one goal post in the middle of the field. The Tang dynasty capital of Chang'an was filled with cuju fields, in the backyards of large mansions, and some were even established in the grounds of the palaces.[10] Soldiers who belonged to the imperial army and Gold Bird Guard often formed cuju teams for the delight of the emperor and his court.[10] The level of female cuju teams also improved. Cuju even became popular amongst the scholars and intellectuals, and if a courtier lacked skill in the game, he could pardon himself by acting as a scorekeeper.[10]

Cuju flourished during the Song dynasty (960–1279) due to social and economic development, extending its popularity to every class in society. At that time, professional cuju players were popular, and the sport began to take on a commercial edge. Professional cuju players fell into two groups: One was trained by and performed for the royal court (unearthed copper mirrors and brush pots from the Song often depict professional performances) and the other consisted of civilians who made a living as cuju players. During this period only one goal post was set up in the center of the field.

It influenced the development in Japan of kemari (蹴鞠), which is still played today on special occasions. The kanji writing (蹴鞠) is the same as for cuju.

Cuju began to decline during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) due to neglect, and the 2,000-year-old sport slowly faded away.

Bronze mirror dating to the Song dynasty

Bronze mirror dating to the Song dynasty

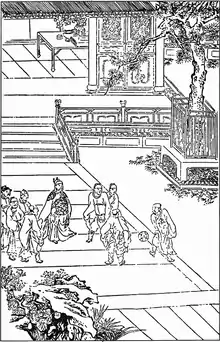

15th century Ming dynasty depiction of cuju, from a printed book of the Water Margin

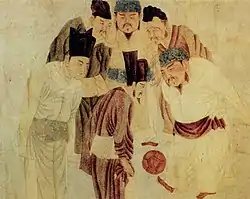

15th century Ming dynasty depiction of cuju, from a printed book of the Water Margin Emperor Taizu of Song playing cuju with Prime Minister Zhao Pu, by the Yuan-era painter Qian Xuan (1235–1305)

Emperor Taizu of Song playing cuju with Prime Minister Zhao Pu, by the Yuan-era painter Qian Xuan (1235–1305) The Xuande Emperor (r. AD 1425–1435) of the Ming dynasty observing court eunuchs playing cuju

The Xuande Emperor (r. AD 1425–1435) of the Ming dynasty observing court eunuchs playing cuju

Kemari at play

Kemari at play

Gameplay

Historically, there were two main styles of cuju: zhuqiu (筑球) and baida (白打).

Zhuqiu was commonly performed at court feasts celebrating the emperor's birthday or during diplomatic events. A competitive cuju match of this type normally consisted of two teams with 12–16 players on each side.

Baida became dominant during the Song dynasty, a style that attached much importance to developing personal skills. Scoring goals became obsolete when using this method with the playing field enclosed using thread and players taking turns to kick the ball within these set limits. The number of fouls made by the players decided the winner. For example, if the ball was not passed far enough to reach other team members, points were deducted. If the ball was kicked too far out, a large deduction from the score would result. Kicking the ball too low or turning at the wrong moment all led to fewer points. Players could touch the balls of other players with any part of the body except their hands, whilst the number of players ranged anywhere from two to ten. In the end, the player with the highest score won.

Cuju clubs

According to Dongjing Meng Hua Lu, in the 10th century, a cuju league, Qi Yun She (齊雲社) was developed in large Chinese cities. Local members were either cuju lovers or professional performers. Nonprofessionals had to formally appoint a professional as their teacher and pay a fee before becoming members.[11][12] This process ensured an income for the professionals, unlike cuju of the Tang dynasty. Qi Yun She organised annual national championships known as Shan Yue Zheng Sai (山岳正賽).

In popular culture

- The Hong Kong TVB series A Change of Destiny features at least one episode based on the cuju competition. Bagua concepts were also used to jinx the opposing team. However, it followed more of the modern soccer rules than the ancient rules of the game.

- John Woo's epic film Red Cliff features a cuju competition with Cao Cao and others observing from the sideline.

- The series The Long Ballad features a cuju competition between the Tang dynasty and the Eastern Turkic Khaganate.

- The Korean series Moon Embracing the Sun features a chugguk competition.

- The Korean series Dream of the Emperor features a chugguk competition between the hwarang and royal inspectors while Princess Deokman is watching; in another scene Kim Chun-chu plays the game with his grandson.

Cuju revival

In 2010, the city of Linzi organized a game of cuju for foreigners and locals in period costumes.[13] Brazilian player Kaká played cuju during his tour while visiting China.[14]

See also

- Chinlone

- Episkyros

- Harpastum

- Knattleikr

- La soule

- Sepak takraw

- List of Chinese inventions

- List of China-related topics

- List of China people

Notes

- 1 2 "History of Football - The Origins". FIFA. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ↑ https://www.fifamuseum.com/en/blog-stories/editorial/origins-cuju-in-china/

- ↑ Team, Editorial (August 22, 2021). "The History Of Soccer". historyofsoccer.info. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- ↑ Barr, Adam. "History of Football: Cuju". Bleacher Report. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ↑ Zhan Guo Ce, Book 8, Strategies of Qi(齊策),"臨淄之中〈姚本臨淄,齊鄙。 鮑本屬齊郡。補曰:青州臨淄縣,古營丘地,城臨淄,故云。見正義及水經注。渤海,後語北海,今青州北海是也。〉七萬戶,臣竊度之,〈姚本度,計。〉下〈鮑本補曰:史無「下」。〉戶三男子,三七二十一萬,不待發於遠縣,而臨淄之卒,固以〈鮑本「以」作「已」。○ 札記今本「以」作「已」。丕烈案:史記作「已」。〉二十一萬矣。臨淄甚富而實,其民無不吹竽、〈鮑本似笙,三十六簧。〉鼓瑟、〈鮑本似琴,二十五弦。〉擊筑、〈鮑本以竹曲五弦之樂。〉彈琴、鬥雞、走犬、六博、蹹踘者;〈鮑本「踘」作「鞠」。○ 劉向別錄,蹙鞠,黃帝作,蓋因娛戲以練武士。「蹹」,即「蹙」也。補曰:王逸云,投六箸,行六棋,謂之六博。「蹹」,史作「蹋」。說文,徒盍反,即「蹹」字。 札記丕烈案:史記作「鞠」。"

- 1 2 Riordan (1999), 32.

- ↑ Records of the Grand Historian,Biography of Su Qin(蘇秦列傳),"臨菑甚富而實,其民無不吹竽鼓瑟,彈琴擊筑,鬬雞走狗,六博蹋鞠者。"

- ↑ "The History of Soccer - History of the Game". Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved August 6, 2008.

- ↑ "Star Wars tops Xmas toy list". msn.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2008. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Benn, 172.

- ↑ Vogel, Hans Ulrich (January 2012). "Homo ludens sinensis: Kickball in China from the 7th to the 16th Centuries". Vivienne Lo (Ed.), Perfect Bodies, Sports, Medicine and Immortality, Pp. 39-58. Retrieved July 7, 2021 – via www.academia.edu.

- ↑ "从高俅发迹说说宋代蹴鞠与齐云社". www.sohu.com. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ↑ "Cuju, archetype of modern game of football". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

- ↑ "Kaka plays ancient Chinese soccer in 'hanfu' (1/5)". www.ecns.cn. Retrieved July 7, 2021.

References

- Benn, Charles (2002). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517665-0.

- James, Riordan (1999). Sport and Physical Education in China. London: Spon Press. ISBN 0-419-22030-5

- Osamu Ike (2014). Kemari in Japan(in Japanese). Kyoto: Mitsumura-Suiko Shoin. ISBN 978-4-8381-0508-3

- Summary in English pp. 181–178. in French pp. 185–182.

External links

![]() Media related to Cuju at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cuju at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)