| Part of a series on |

| Kabbalah |

|---|

|

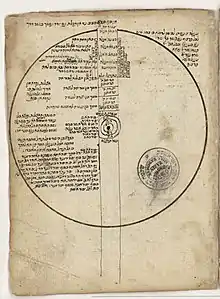

The tzimtzum or tsimtsum (Hebrew: צמצום ṣimṣum "contraction/constriction/condensation") is a term used in the Lurianic Kabbalah to explain Isaac Luria's doctrine that God began the process of creation by "contracting" his Ohr Ein Sof (infinite light) in order to allow for a "conceptual space" in which finite and seemingly independent realms could exist. This primordial initial contraction, forming a ḥalal hapanuy "vacant space" (חלל הפנוי) into which new creative light could beam, is denoted by general reference to the tzimtzum. In Kabbalistic interpretation, tzimtzum gives rise to the paradox of simultaneous divine presence and absence within the vacuum and resultant Creation. Various approaches exist then, within Orthodoxy, as to how the paradox may be resolved, and as to the nature of tzimtzum itself. [1]

Function

Because the tzimtzum results in the "empty space" in which spiritual and physical Worlds and ultimately, free will can exist, God is often referred to as "Ha-Makom" (המקום lit. "the Place", "the Omnipresent") in Rabbinic literature ("He is the Place of the World, but the World is not His Place"[2]). Relatedly, Olam—the Hebrew for "World/Realm"—is derived from the root עלם meaning "concealment". This etymology is complementary with the concept of Tzimtzum in that the subsequent spiritual realms and the ultimate physical universe conceal to different degrees the infinite spiritual lifeforce of creation.

Their progressive diminutions of the divine Ohr (Light) from realm to realm in creation are also referred to in the plural as secondary tzimtzumim (innumerable "condensations/veilings/constrictions" of the lifeforce). However, these subsequent concealments are found in earlier, Medieval Kabbalah. The new doctrine of Luria advanced the notion of the primordial withdrawal (a dilug – radical "leap") in order to reconcile a causal creative chain from the Infinite with finite Existence.

Prior to Creation, there was only the infinite Or Ein Sof filling all existence. When it arose in G-d's Will to create worlds and emanate the emanated ... He contracted (in Hebrew "tzimtzum") Himself in the point at the center, in the very center of His light. He restricted that light, distancing it to the sides surrounding the central point, so that there remained a void, a hollow empty space, away from the central point ... After this tzimtzum ... He drew down from the Or Ein Sof a single straight line [of light] from His light surrounding [the void] from above to below [into the void], and it chained down descending into that void. ... In the space of that void He emanated, created, formed and made all the worlds.

Inherent paradox

A commonly held[4] understanding in Kabbalah is that the concept of tzimtzum contains a built-in paradox, requiring that God be simultaneously transcendent and immanent. Viz.: On the one hand, if the "Infinite" did not restrict itself, then nothing could exist—everything would be overwhelmed by God's totality. Existence thus requires God's transcendence, as above. On the other hand, God continuously maintains the existence of, and is thus not absent from, the created universe.

The Divine life-force which brings all creatures into existence must constantly be present within them ... were this life-force to forsake any created being for even one brief moment, it would revert to a state of utter nothingness, as before the creation.[5]

Rabbi Nachman of Breslav discusses this inherent paradox as follows:

Only in the future will it be possible to understand the Tzimtzum that brought the "Empty Space" into being, for we have to say of it two contradictory things ... [1] the Empty Space came about through the Tzimtzum, where, as it were, He 'limited' His Godliness and contracted it from there, and it is as though in that place there is no Godliness ... [2] the absolute truth is that Godliness must nevertheless be present there, for certainly nothing can exist without His giving it life.

Hasdai Crescas in “Or Hashem”[6] explains that over the limits of world of finitude of shape it can be said that God is living forever with eternal attribute of Infinite, i.e. His essence over time and space:

If an infinite body existed, it would move either circularly or rectilinearly. If circularly, it would have to have a center, because what is circular is that which circles around a center. But if it has a center, it also has extremities. But an infinite thing has no extremities. Hence it cannot move circularly. The remaining possibility is that it moves rectilinearly, but if so, it requires necessarily two places, each of them infinite. One would be for natural motion and it would be a that-to-which, and the second would be for forcible motion and it would be a that-from-which. But if the places are two, they will necessarily be finite, since what is infinite cannot be two in number. Yet they were assumed to be infinite. Thus it [viz. an infinite body] cannot move rectilinearly. Moreover, the place cannot be infinite since it is bounded, for it was shown with respect to it that it is an encompassing limit

— Hasdai Crescas, Or Hashem

This “material-World” is “inside God”, with earth and universe: God is infinite but the World and Universe are finites, so the centre of God is not possible, because of His Infinite-essence; God is infinite with the World with nature, humankind, animals, etc. “Inside-Him”.

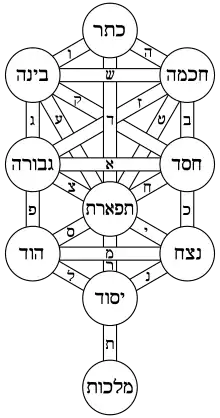

Lurianic thought

Isaac Luria introduced four central themes into kabbalistic thought, tzimtzum, Shevirat HaKelim (the shattering of the vessels), Tikkun (repair), and Partzufim. These four are a group of interrelated, and continuing, processes. Tzimtzum describes the first step in the process by which God began the process of creation by withdrawing his own essence from an area, creating an area in which creation could begin and where he could exist as reshimu (residue) in all empty spaces in the world.[7] Shevirat HaKelim describes how, after the tzimtzum, God created the vessels (HaKelim) in the empty space, and how when God began to pour his Light into the vessels they were not strong enough to hold the power of God's Light and shattered (Shevirat). The third step, Tikkun, is the process of gathering together, and raising, the sparks of God's Light that were carried down with the shards of the shattered vessels.[8]

Since tzimtzum is connected to the concept of exile, and Tikkun is connected to the need to repair the problems of the world of human existence, Luria unites the cosmology of Kabbalah with the practice of Jewish ethics, and makes ethics and traditional Jewish religious observance the means by which God allows humans to complete and perfect the material world through living the precepts of a traditional Jewish life.[9] Thus, in contrast to earlier, Medieval Kabbalah, this made the first creative act a concealment/divine exile rather than unfolding revelation. This dynamic crisis-catharsis in the divine flow is repeated throughout the Lurianic scheme.

Chabad view

In Chabad Hassidism the concept of tzimtzum is understood as not meant to be interpreted literally, but rather to refer to the manner in which God impresses his presence upon the consciousness of finite reality:[10] thus tzimtzum is not only seen as being a real process but is also seen as a doctrine that every person is able, and indeed required, to understand and meditate upon.

In the Chabad view, the function of the tzimtzum was "to conceal from created beings the activating force within them, enabling them to exist as tangible entities, instead of being utterly nullified within their source".[11] The tzimtzum produced the required "vacated space" (chalal panui חלל פנוי, chalal חלל), devoid of direct awareness of God's presence.

Vilna Gaon's view

The Vilna Gaon held that tzimtzum was not literal, however, the "upper unity", the fact that the universe is only illusory, and that tzimtzum was only figurative, was not perceptible, or even really understandable, to those not fully initiated in the mysteries of Kabbalah.[12]

Others say that Vilna Gaon held the literal view of the tzimtzum.[13]

Shlomo Elyashiv articulates this view clearly (and claims that not only is it the opinion of the Vilna Gaon, but also is the straightforward and simple reading of Luria and is the only true understanding).

He writes:

I have also seen some very strange things in the words of some contemporary kabbalists who explain things deeply. They say that all of existence is only an illusion and appearance, and does not truly exist. This is to say that the ein sof didn't change at all in itself and its necessary true existence and it is now still exactly the same as it was before creation, and there is no space empty of Him, as is known (see Nefesh Ha-Chaim Shaar 3). Therefore they said that in truth there is no reality to existence at all, and all the worlds are only an illusion and appearance, just as it says in the verse "in the hands of the prophets I will appear" (Hoshea 12: 11). They said that the world and humanity have no real existence, and their entire reality is only an appearance. We perceive ourselves as if we are in a world, and we perceive ourselves with our senses, and we perceive the world with our senses. It turns out [according to this opinion] that all of existence of humanity and the world is only a perception and not in true reality, for it is impossible for anything to exist in true reality, since He fills all the worlds. ...

How strange and bitter is it to say such a thing. Woe to us from such an opinion. They don’t think and they don't see that with such opinions they are destroying the truth of the entire Torah.[14]

However, the Gaon and Elyashiv held that tzimtzum only took place in God's will (Ratzon), but that it is impossible to say anything at all about God himself (Atzmus). Thus, they did not actually believe in a literal tzimtzum in God's essence. Luria's Etz Chaim itself, however, in the First Shaar, is ambivalent: in one place it speaks of a literal tzimtzum in God's essence and self, then it changes a few lines later to a tzimtzum in the divine light (an emanated, hence created and not part of God's self, energy).

History and Hester Panim

"Who healeth the broken in heart, and bindeth up their wounds." This indicates God's power. If the heart is broken, that is, if its parts are severed, there is no natural cure for it, as we are told by medical writers. Any other members if broken can be cured. Therefore the Psalmist attributes to the Lord the cure of a broken heart, in which the parts are severed, though it can not be cured in the ord nary way. This shows His great power in delivering the oppressed from his oppressor, as David says, "The Lord is nigh unto them that are of a broken heart, and saveth such as are of a contrite spirit." The meaning is that just as God cures the broken hearted, who could not recover if left to nature, so He saves those of a crushed spirit, who can not be saved in a natural way, as Solomon says: "The spirit of a man will sustain his infirmity; but a broken spirit who can bear?" The meaning is, if a man is sick and the animal spirit is strong, he can sustain the infirmity, but if the spirit is sick and broken, who can bear it? That is, who can sustain it? For by nature it can not get well[15]

In the modern era, Shoah has been the subject of discussion about theological thinking: the Hester Panim is a part of modern exegesis. Tzimtzum is a process before Creation but during history the same "structure" is even present, as modern philosophy like to know. The characteristic of Shoah is part of individual life and a part of this structure of history:

This is comparable to someone walking down in the deep darkness of night. He was afraid of thorns and wells, of wild beasts and bandits; not knowing where he was walking on. Finding a burning torch, he got rid of thorns and pits, but he still feared wild beasts and bandits ... not knowing where he was on. At dawn, he was saved from the wild beasts and bandits, but he still did not know where he was on. When he came to a crossroads, he was saved from all of them. ... What is this crossroads? Rav Chisda says: "It is the Talmid chacham and the day of death" (Talmud, Sotah 21a)

On the contrary one who would study Torah but he lost himself in vanity of the world is like a person without Nefesh, a soul, i.e. without true faith:

Similarly, R. Chaim Vital also describes431 this sin as excluding one from the World to Come, 'weaving it in the same weave'432 there, equating it with the cases that Chazal state for whom "Gehinom will end but for them it will not come to an end!,"433 the Merciful One should save us. The Rambam and Beit Yosef in the above references [also determine the Halacha] of one who did study and review but then stopped doing so and instead engaged in the emptiness of this world, neglecting his studies, as having the same judgment as one who was able to study Torah and did not. Similarly, in [his] judgment, that his actions which were not good distance him, 'and his sin withholds the good from him'434 as he was able to involve himself with and engage in Torah study, and 'out of intentional sin'435 and 'contempt of the soul'436 chose 'and took a bad purchase for himself,'437 others, and all the worlds despising the everlasting life of the Holy Torah – the life and light of all the worlds – through which he was attached, so to speak, with God, Who gives life to all but stretched out his hand to destroy the palace of the King – diminishing, darkening, and extinguishing the bestowal of light in the worlds and also of his own soul. Why should he have true life? as he prevented himself from seeing the light of everlasting life and he cannot tolerate the greatness of the intensity of the Supernal Light as he has not experienced it while being in this world and he is exiled and automatically cut off from Eden, God's Garden preventing himself from 'being bound with the bond of life with YHVH his God,'438 'going from bad to worse',439 God forbid. Woe for that shame! Similarly, Chazal determined his fate, 'that his hope is decreed as lost'440 forever, God forbid, that he also 'will everlastingly not see light'441 that he will not 'live again forever'442 at the end of days when 'those sleeping in the dust of the ground will awaken for everlasting life'…[16]

During the Shoah much persons had not power and "energy" to study Torah and to do Mitzvot, so Chazal suggest to have "Torah study" all time, day and night… because the time of "bad-decrees" over them could have been very danger by "a Govern … as dog-face".[17]

Chazal teaches that all Jews must say: "All universe is created for me", so God has created the World with "pillars" of Heavens and Earth, i.e. Chokhmah and Binah… Torah is the light of God and "Torah Study" can be the life of the universe and of "myriads of worlds" to not destroy the Creation.[18]

Application in clinical psychology

An Israeli professor, Mordechai Rotenberg, believes the Kabbalistic-Hasidic tzimtzum paradigm has significant implications for clinical therapy. According to this paradigm, God's "self-contraction" to vacate space for the world serves as a model for human behavior and interaction. The tzimtzum model promotes a unique community-centric approach which contrasts starkly with the language of Western psychology.[19]

HaKolKoreh is the first organization established exclusively according to the Rotenberg Institute ethos. Using psychodrama as a platform for change, HaKolKoreh offers a year- long study course to educators and therapists, with an emphasis on Jewish texts and Jewish approaches that enhance established psychotherapeutic theories. HakolKoreh uses psychodrama and theatrical psychotherapy intertwined with the language of Jewish-Hassidic philosophy, as a platform for using language as a tool for bringing internal peace and peace between ourselves and others. The psychodrama practitioners who attended the training report that their ability to work with people in grief was significantly enhanced[20]

In popular culture

Tsimtsum is central to the plot of Aryeh Lev Stollman's 1997 novel The Far Euphrates.

Tzimtzum is mentioned as a topic of fascination for Nahman Samuel ben Levi of Busk and his friend Leybko in Olga Tokarczuk's novel The Books of Jacob.

Tsim Tsum is the title of a collection of vignettes by Sabrina Orah Mark (published 2009).

In Yann Martel's novel Life of Pi and its 2012 film adaptation, a cargo ship called the Tsimtsum sinks at a pivotal point of the plot. The story deals with the existence or non-existence of a divine power, and the sinking of the ship marks the creation of the universe in the novel's allegory.

See also

Notes

- ↑ See, for a survey, Rabbi David Sedley (2008). "The Perception of Reality: contrasting views of the nature of existence", Reshimu Journal

- ↑ Parshat Vayeitzei: Yalkut Shimoni on the verse "He arrived..." Also, alternate sages in Midrash Bereishit Rabbah 68:9. HaMakom article Archived 2010-07-05 at the Wayback Machine, inner.org

- ↑ Rabbi Moshe Miller. "The Great Constriction". KabbalaOnline.org. Archived from the original on 2005-01-24.

- ↑ see for example Aryeh Kaplan, "Paradoxes" (in "The Aryeh Kaplan Reader", Artscroll 1983. ISBN 0-89906-174-5)

- ↑ "Chapter 2 - Shaar Hayichud Vehaemunah". Chabad.org. 2014-07-03. Retrieved 2015-02-25.

- ↑ Light of the Lord (Or Hashem). Ḥasdai Crescas Oxford University Press, New York 2018 ISBN 978–0–19–872489–6

- ↑ Falcon, Ted; Blatner, David (2019). Judaism for Dummies (2nd ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 76. ISBN 978-1-119-64307-4. OCLC 1120116712.

- ↑ James David Dunn, Windows of the Soul, p.21-24

- ↑ J.H. Laenen, Jewish Mysticism, p.168-169

- ↑ "Tzimtzum: Contraction". Inner.org. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ↑ Tanya, Shaar Hayichud veHaEmunah, ch.4

- ↑ E. J. Schochet, The Hasidic Movement and the Gaon of Vilna

- ↑ Allan Nadler, The Faith of the Mithnagdim

- ↑ Leshem Sh-vo ve-Achlama Sefer Ha-Deah drush olam hatohu chelek 1, drush 5, siman 7, section 8 (p. 57b)

- ↑ Albo, Joseph. Sefer HaIkkarim: Joseph Albo's Fundamentals of Judaism (pp.343–344)

- ↑ Chaim of Volozhin (Nefesh haTzimtzum)

- ↑ Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai (Zohar)

- ↑ In Chassidism of Chabad God could destroy the entire World in a instant, so in Judaism the "Torah Study" is the life and the holy salvation … even by one Jew alone … who studies the Sages of Torah:

Then, those who out of their poor choice are totally uninvolved with Torah 'descend to the abyss while alive'450 'and have driven themselves away from attaching to the heritage of the servants of God'451 who cleave to God and His Torah and 'are cut off from the land of life,'452 God forbid [this is] at the very least in this world, if not also in all of the worlds, whose holiness and light have also been diminished and lowered as a result of these sins for which they are culpable with their lives and 'almost turn their feet'453 to destruction, God forbid, as per Chazal: All the while that people disassociate themselves with the Torah, God seeks to destroy the world.454 "for the pillars of the world are God's and upon them He set the world" – pillars refers to Torah Sages. ... Every day Angels of Destruction are sent by God to totally destroy the world and if it weren't for the prayer and study halls where Torah Sages sit and involve themselves with words of Torah, they would immediately destroy the entire world.455 Refer there. With all this, [the worlds] are still able to exist through [the efforts of] 'the survivors who God calls'456 who involve themselves in the Holy Torah day and night such that they do not totally return to a state of null and void, God forbid. However, if the world were, God forbid, completely void, even literally for one moment, of involvement and analysis of the Chosen People with the Holy Torah then all the worlds would immediately be destroyed and totally cease to be, God forbid. Notwithstanding, even a single talented Jew alone has the ability to cause the establishment and continuation of all the worlds and the Creation in its entirety by his involvement with and analysis of the Holy Torah for its sake, as per Chazal: Whoever is involved with Torah for its sake. ... R. Yochanan says he even protects the entire world

— Chaim of Volozhin - ↑ "Rotenberg Center for Jewish Psychology". Jewishpsychology.org. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ↑ Case studies (www.jewishpsychology.org)

References

- Jacob Immanuel Schochet, Mystical Concepts in Chassidism, especially chapter II, Kehot 1979,3rd revised edition 1988. ISBN 0-8266-0412-9

- Aryeh Kaplan, "Paradoxes", in "The Aryeh Kaplan Reader", Artscroll 1983. ISBN 0-89906-174-5

- Aryeh Kaplan, "Innerspace", Moznaim Pub. Corp. 1990. ISBN 0-940118-56-4

- Aryeh Kaplan Understanding God Archived 2008-12-22 at the Wayback Machine, Ch2. in "The Handbook of Jewish Thought", Moznaim 1979. ISBN 0-940118-49-1

External links

- Tzimtzum: A Primer, chabad.org

- Tanya, Shaar HaYichud VehaEmunah Shneur Zalman of Liadi—see Lessons in Tanya, chabad.org

- Shaar HaYichud - The Gate of Unity Archived 2018-10-10 at the Wayback Machine, Dovber Schneuri — a detailed explanation of the concept of Tzimtzum.

- Veyadaata - To Know G-d, Sholom Dovber Schneersohn, a Hasidic discourse on the paradox of Tzimtzum

- inner.org, "Basics in Kabbalah and Chassidut"

- Tanya: Tzimtzum and armony of economy in the world with Tzedakah (www.chabad.org)