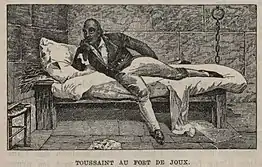

Toussaint Louverture | |

|---|---|

Posthumous 1813 painting of Louverture | |

| Governor-General of Saint-Domingue | |

| In office 1797–1802 | |

| Appointed by | Étienne Maynaud |

| Preceded by | Léger-Félicité Sonthonax |

| Succeeded by | Charles Leclerc |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 20 May 1743 Cap-Français, Saint-Domingue |

| Died | 7 April 1803 (aged 59) Fort de Joux, La Cluse-et-Mijoux First French Republic |

| Spouse(s) | Cécile Suzanne Simone Baptiste Louverture |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Spanish Army French Army French Revolutionary Army Armée Indigène[1] |

| Years of service | 1791–1803 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Haitian Revolution |

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture (French: [fʁɑ̃swa dɔminik tusɛ̃ luvɛʁtyʁ], English: /ˌluːvərˈtjʊər/)[2] also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda; 20 May 1743 – 7 April 1803) was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louverture first fought and allied with Spanish forces against St. Dominican Royalists, then joined with Republican France, becoming Governor-General-for-life of Saint-Domingue, and lastly fought against Napoleon Bonaparte's Empire.[3][4] As a revolutionary leader, Louverture displayed military and political acumen that helped transform the fledgling slave rebellion into a revolutionary movement. Louverture is now known as the "Father of Haiti".[5]

Toussaint Louverture was born as a slave in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, now known as Haiti. He was a devout Catholic, and was manumitted as an affranchi (ex-slave) before the French Revolution, identifying as a Creole for the greater part of his life. During his time as an affranchi, he became a salaried employee, an overseer of his former master's plantation, and later became a wealthy slave owner himself; Toussaint Louverture owned several coffee plantations at Petit Cormier, Grande Rivière, and Ennery.[6][7][8]

At the start of the Haitian revolution he was nearly 50 years old and began his military career as a lieutenant to Georges Biassou, an early leader of the 1791 War for Freedom in Saint-Domingue.[9] Initially allied with the Spaniards of neighboring Santo Domingo, Louverture switched his allegiance to the French when the new Republican government abolished slavery. Louverture gradually established control over the whole island and used his political and military influence to gain dominance over his rivals.[10]

Throughout his years in power, he worked to balance the economy and security of Saint-Domingue. Worried about the economy, which had stalled, he restored the plantation system using paid labor; negotiated trade agreements with the United Kingdom and the United States and maintained a large and well-trained army.[11] Louverture seized power in Saint-Domingue, established his own system of government, and promulgated his own colonial constitution in 1801 that named him as Governor-General for Life, which challenged Napoleon Bonaparte's authority.[12]

In 1802, he was invited to a parley by French Divisional General Jean-Baptiste Brunet, but was arrested upon his arrival. He was deported to France and jailed at the Fort de Joux. He died in 1803. Although Louverture died before the final and most violent stage of the Haitian Revolution, his achievements set the grounds for the Haitian army's final victory. Suffering massive losses in multiple battles at the hands of the Haitian army and losing thousands of men to yellow fever, the French capitulated and withdrew permanently from Saint-Domingue the very same year. The Haitian Revolution continued under Louverture's lieutenant, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who declared independence on 1 January 1804, thereby establishing the sovereign state of Haiti.

Early life

Birth, parentage, and childhood

Louverture was born into slavery, the eldest son of Hyppolite, an Allada slave from the slave coast of West Africa, and his second wife Pauline, a slave from the Aja ethnic group, and given the name Toussaint at birth.[10] Louverture's son Issac would later name his great-grandfather, Hyppolite's father, as Gaou Guinou and a son of the King of Allada, although there is little extant evidence of this. The name Gaou possibly originated in the title Deguenon, meaning "old man" or "wise man" in the Allada kingdom, making Gaou Guinou and his son Hyppolite members of the bureaucracy or nobility, but not members of the royal family. In Africa, Hyppolite and his first wife, Catherine, were forced into enslavement due to a series of imperialist wars of expansion by the Kingdom of Dahomey into the Allada territory. In order to remove their political rivals and obtain European trade goods, Dahomean slavers separated the couple and sold them to the crew of the French slave ship Hermione, which then sailed to the French West Indies. The original names of Toussaint's parents are unknown, since the Code Noir mandated that slaves brought to their colonies be made into Catholics, stripped of their African names, and be given more European names in order to assimilate them into the French plantation system. Toussaint's father received the name Hyppolite upon his baptism on Saint-Domingue, as Latin and Greek names were the most fashionable for slaves at this time, followed by French, and Biblical Christian names.[10]

Louverture is thought to have been born on the plantation of Bréda at Haut-du-Cap in Saint-Domingue, where his parents were enslaved and where he would spend the majority of his life before the revolution.[13][14] His parents would go on to have several children after him, with five surviving infancy; Marie-Jean, Paul, Pierre, Jean, and Gaou, named for his grandfather. Louverture would grow closest to his younger brother Paul, who along with his other siblings were baptized into the Catholic Church by the local Jesuit Order. Pierre-Baptiste Simon, a carpenter and gatekeeper on the Bréda plantation, is considered to have been Louverture's godfather and went on to become a parental figure to Louverture's family, along with his foster mother Pelage, after the death of Toussaint's parents.[15] Growing up, Toussaint first learned to speak the African Fon language of the Allada slaves on the plantation, then the Creole French of the greater colony, and eventually the Standard French of the elite class (grands blancs) during the revolution.

Although he would later become known for his stamina and riding prowess, Louverture earned the nickname Fatras-Bâton ("sickly stick"), in reference to his small thin stature in his youth.[16][17]: 26–27 Toussaint and his siblings were trained to be domestic servants with Louverture being trained as an equestrian and coachmen after showing a talent for handling the horses and oxen on the plantation. This allowed the siblings to work in the manor house and stables, away from the grueling physical labor and deadly corporal punishment meted out in the sugar-cane fields. In spite of this relative privilege, there is evidence that even in his youth Louverture's pride pushed him to engage in fights with members of the Petits-blancs (white commoner) community, who worked on the plantation as hired help. There is a record that Louverture beat a young petit blanc named Ferere, but was able to escape punishment after being protected by the new plantation overseer, François Antoine Bayon de Libertat. De Libertat had become steward of the Bréda property after it was inherited by Pantaléon de Bréda Jr., a grand blanc (white nobleman), and managed by Bréda's nephew the Count of Noah.[18] In spite or perhaps because of this protection, Louverture went on to engage in other fights. On one occasion, he threw the plantation attorney Bergé off a horse belonging to the Bréda plantation, when he attempted to take it outside the bounds of the property without permission.[10]

First marriage and manumission

Until 1938, historians believed that Louverture had been a slave until the start of the revolution.[note 1] In the later 20th century, discovery of a personal marriage certificate and baptismal record dated between 1776 and 1777 documented that Louverture was a freeman, meaning that he had been manumitted sometime between 1772 and 1776, the time de Libertat had become overseer. This finding retrospectively clarified a private letter that Louverture sent to the French government in 1797, in which he mentioned he had been free for more than twenty years.[19]: 62

Upon being freed, Toussaint took up the name of Toussaint de Bréda (Toussaint of Bréda), or more simply Toussaint Bréda, in reference to the plantation where he grew up. Toussaint went from being a slave of the Bréda plantation to becoming a member of the greater community of gens de couleur libres (free people of color). This was a diverse group of Affranchis (freed slaves), free blacks of full or majority African ancestry, and Mulattos (mixed-race peoples), which included the children of French planters and their African slaves, as well as distinct multiracial families who had multi-generational mixed ancestries from the varying different populations on the island. The gens de couleur libres strongly identified with Saint-Domingue, with a popular slogan being that while the French felt at home in France, and the slaves felt at home in Africa, they felt at home on the island. Now enjoying a greater degree of relative freedom, Louverture dedicated himself to building wealth and gaining further social mobility through emulating the model of the grands blancs and rich gens de couleur libres by becoming a planter. He began by renting a small coffee plantation, along with its 13 slaves, from his future son-in-law.[20] One of the slaves Louverture owned at this time is believed to have been Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who would go onto become one of Louverture's most loyal lieutenants and a member of his personal guard during the Haitian Revolution.[21]

Between 1761 and 1777, Louverture met and married his first wife, Cécile, in a Catholic ceremony. The couple went on to have two sons, Toussaint Jr. and Gabrielle-Toussaint, and a daughter, Marie-Marthe. During this time, Louverture bought several slaves; although this was a means to grow a greater pool of exploitable labor, this was one of the few legal methods available to free the remaining members of a former slave's extended family and social circle. Louverture eventually bought the freedom of Cécile, their children, his sister Marie-Jean, his wife's siblings, and a slave named Jean-Baptist, freeing him so that he could legally marry. Louverture's own marriage, however, soon became strained and eventually broke down, as his coffee plantation failed to make adequate returns. A few years later, the newly freed Cécile left Louverture for a wealthy Creole planter, while Louverture had begun a relationship with a woman named Suzanne, who is believed to have gone on to become his second wife. There is little evidence that any formal divorce occurred, as that was illegal at the time. Louverture, in fact, would go on to completely excise his first marriage from his recollections of his pre-revolutionary life, to the extent that, until recent documents uncovered the marriage, few researchers were aware of the existence of Cécile and her children with Louverture.[10]

Second marriage

In 1782, Louverture married his second wife, Suzanne Simone-Baptiste, who is thought to have been his cousin or the daughter of his godfather Pierre-Baptiste.[19]: 263 Toward the end of his life, Louverture told General Caffarelli that he had fathered at least 16 children, of whom 11 had predeceased him, between his two wives and a series of mistresses.[19]: 264–267 In 1785, Louverture's eldest child, the 24-year-old Toussaint Jr., died from a fever and the family organized a formal Catholic funeral for him. This was officiated by a local priest as a favor for the devout Louverture. Gabrielle-Toussaint disappeared from the historical record at this time and is presumed to have also died, possibly from the same illness that took Toussaint Jr. Not all of Louverture's children can be identified with certainty, but the three children from his first marriage and his three sons from his second marriage are well known. Suzanne's eldest child, Placide, is generally thought to have been fathered by Seraphim Le Clerc, a Creole planter. In spite of this, Placide was adopted by Louverture and raised as his own. Louverture went on to have at least two sons with Suzanne: Isaac, born in 1784, and Saint-Jean, born in 1791. They would remain enslaved until the start of the revolution, as Louverture spent the 1780s attempting to regain the wealth he had lost with the failure of his coffee plantation in the 1770s.[19]: 264–267

It appears that during this time Louverture returned to play an important role on the Bréda plantation to remain closer to old friends and his family. He remained there until the outbreak of the revolution as a salaried employee and contributed to the daily functions of the plantation.[22] He took up his old responsibilities of looking after the livestock and care of the horses.[23] By 1789, his responsibilities expanded to include acting as a muleteer, master miller, and possibly a slave-driver, charged with organizing the workforce. During this time the Bréda family attempted to divide the plantation and the slaves on it among a new series of four heirs. In an attempt to protect his foster mother, Pelage, Louverture bought a young 22-year-old female slave and traded her to the Brédas to prevent Pelage from being sold to a new owner. By the start of the revolution, Louverture began to accumulate a moderate fortune and was able to buy a small plot of land adjacent to the Bréda property to build a house for his family. He was nearly 48 years old at this time.[20]

Education

Louverture gained some education from his godfather Pierre-Baptiste on the Bréda plantation.[24] His extant letters demonstrate a moderate familiarity with Epictetus, the Stoic philosopher who had lived as a slave, while his public speeches showed a familiarity with Machiavelli.[25] Some cite Enlightenment thinker Abbé Raynal, a French critic of slavery, and his publication Histoire des deux Indes predicting a slave revolt in the West Indies as a possible influence.[25][17]: 30–36 [note 2]

Louverture received a degree of theological education from the Jesuit and Capuchin missionaries through his church attendance and devout Catholicism. His medical knowledge is attributed to a familiarity with the folk medicine of the African plantation slaves and Creole communities, as well as more formal techniques found in the hospitals founded by the Jesuits and the free people of color.[28] Legal documents signed on Louverture's behalf between 1778 and 1781 suggest that he could not yet write at that time.[29][19]: 61–67 Throughout his military and political career during the revolution, he was known to have verbally dictated his letters to his secretaries, who prepared most of his correspondences. A few surviving documents from the end of his life in his own hand confirm that he eventually learned to write, although his Standard French spelling was "strictly phonetic" and closer to the Creole French he spoke for the majority of his life.[25][30][31]

Haitian Revolution

Beginnings of a rebellion: 1789–1793

Beginning in 1789, the black and mulatto population of Saint-Domingue became inspired by a multitude of factors that converged on the island in the late 1780s and early 1790s leading to them organize a series of rebellions against the central white colonial assembly in Le Cap. In 1789 two mix-race Creole merchants, Vincent Ogé and Julien Raimond, happened to be in France during the early stages of the French Revolution. Here they began lobbying the French National Assembly to expand voting rights and legal protections from the grands blancs to the wealthy slave-owning gens de couleur, such as themselves. Being of majority white descent and with Ogé having been educated in France, the two were incensed that their black African ancestry prevented them from having the same legal rights as their fathers, who were both grand blanc planters. Rebuffed by the assembly they return to the colony where Ogé met up with Jean-Baptiste Chavannes, a wealthy mixed-race veteran of the American Revolution and an abolitionist. Here the two organized a small scale revolt in 1790 composed of a few hundred gens de couleur, who engaged in several battles against the colonial militias on the island. However, after the movement failed to gain traction Ogé and Chavannes were quickly captured and publicly broken on the wheel in the public square in Le Cap in February 1791. For the slaves on the island worsening conditions due to the neglect of legal protections afforded them by the Code Noir stirred animosities and made a revolt more attractive compared to the continued exploitation by the grands and petits blancs. Then the political and social disability caused by the French Revolution's attempt to expand the rights to all men, inspired a series of revolts across several neighboring French possessions in the Caribbean, which upset much of the established trade between the colonies. Many of the devout Catholic slaves and freedmen, including Toussaint, identified as free Frenchmen and royalists, who desired to protect a series of progressive legal protections afforded to the black citizenry by King Louis XVI and his predecessors.[10]

On 14 August 1791, two hundred members of the black and mixed-race population made up of slave foremen, Creoles, and freed slaves gathered in secret at a plantation in Morne-Rouge in the north of Saint-Domingue to plan their revolt. Here prominent early figures of the revolution such as Dutty François Boukman, Jean-François Papillon, Georges Biassou, Jeannot Bullet, and Toussaint gathered to nominate a single leader to guide the revolt. Toussaint, wary of the dangers of taking on such a public role, especially after hearing about what happened to Ogé and Chavannes, went on to nominate Georges Biassou as leader. He would later join his forces as a secretary and lieutenant, and be in command of a small detachment of soldiers.[32][33] During this time Toussaint took up the name of Monsieur Toussaint, a title that was once been reserved for the white population of Saint-Domingue. Surviving documents show him participating in the leadership of the rebellion, discussing strategy, and negotiating with the Spanish supporters of the rebellion for supplies. Wanting to identify with the royalist cause Louverture and other rebels wore white cockades upon their sleeves and crosses of St. Louis.[22]

A few days after this gathering, a Vodou ceremony at Bois Caïman marked the public start of the major slave rebellion in the north, which had the largest plantations and enslaved population. Louverture did not openly take part in the earliest stages of the rebellion, as he spent the next few weeks sending his family to safety in Santo Domingo and helping his old overseer Bayon de Libertat. Louverture hid him and his family in a nearby wood, and brought them food from a nearby rebel camp. He eventually helped Bayon de Libertat's family escape the island and in the coming years supported them financially as they resettled in the United States and mainland France.[10]

In 1791, Louverture was involved in negotiations between rebel leaders and the French Governor, Blanchelande, for the release of their white prisoners and a return to work, in exchange for a ban on the use of whips, an extra non-working day per week, and the freedom of imprisoned leaders.[34] When the offer was rejected, he was instrumental in preventing the massacre of Biassou's white prisoners.[35] The prisoners were released after further negotiations and escorted to Le Cap by Louverture. He hoped to use the occasion to present the rebellion's demands to the colonial assembly, but they refused to meet.[36]

Throughout 1792, as a leader in an increasingly formal alliance between the black rebellion and the Spanish, Louverture ran the fortified post of La Tannerie and maintained the Cordon de l'Ouest, a line of posts between rebel and colonial territory.[37] He gained a reputation for his discipline, training his men in guerrilla tactics and "the European style of war".[38] After hard fighting, he lost La Tannerie in January 1793 to the French General Étienne Maynaud de Bizefranc de Laveaux, but it was in these battles that the French first recognized him as a significant military leader.[39]

Some time in 1792–1793, Toussaint adopted the surname Louverture, from the French word for "opening" or "the one who opened the way".[40] Although some modern writers spell his adopted surname with an apostrophe, as in "L'Ouverture", he did not. The most common explanation is that it refers to his ability to create openings in battle. The name is sometimes attributed to French commissioner Polverel's exclamation: "That man makes an opening everywhere". Some writers think the name referred to a gap between his front teeth.[41]

Alliance with the Spanish: 1793–1794

Despite adhering to royalist views, Louverture began to use the language of freedom and equality associated with the French Revolution.[42] From being willing to bargain for better conditions of slavery late in 1791, he had become committed to its complete abolition.[43][44] After an offer of land, privileges, and recognizing the freedom of slave soldiers and their families, Jean-François and Biassou formally allied with the Spanish in May 1793; Louverture likely did so in early June. He had made covert overtures to General Laveaux prior but was rebuffed as Louverture's conditions for alliance were deemed unacceptable. At this time the republicans were yet to make any formal offer to the slaves in arms and conditions for the blacks under the Spanish looked better than that of the French.[45] In response to the civil commissioners' radical 20 June proclamation (not a general emancipation, but an offer of freedom to male slaves who agreed to fight for them) Louverture stated that "the blacks wanted to serve under a king and the Spanish king offered his protection."[46]

On 29 August 1793, he made his famous declaration of Camp Turel to the black population of St. Domingue:

Brothers and friends, I am Toussaint Louverture; perhaps my name has made itself known to you. I have undertaken vengeance. I want Liberty and Equality to reign in St. Domingue. I am working to make that happen. Unite yourselves to us, brothers and fight with us for the same cause.[26]

On the same day, the beleaguered French commissioner, Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, proclaimed emancipation for all slaves in French Saint-Domingue,[47] hoping to bring the black troops over to his side.[48] Initially, this failed, perhaps because Louverture and the other leaders knew that Sonthonax was exceeding his authority.[49]

However, on 4 February 1794, the French revolutionary government in France proclaimed the abolition of slavery.[50] For months, Louverture had been in diplomatic contact with the French general Étienne Maynaud de Bizefranc de Laveaux. During this time, his competition with the other rebel leaders was growing, and the Spanish had started to look with disfavor on his near-autonomous control of a large and strategically important region.[51]

Louverture's auxiliary force was employed to great success, with his army responsible for half of all Spanish gains north of the Artibonite in the West in addition to capturing the port town of Gonaïves in December 1793.[52] However, tensions had emerged between Louverture and the Spanish higher-ups. His superior with whom he enjoyed good relations, Matías de Armona, was replaced with Juan de Lleonart – who was disliked by the black auxiliaries. Lleonart failed to support Louverture in March 1794 during his feud with Biassou, who had been stealing supplies for Louverture's men and selling their families as slaves. Unlike Jean-François and Bissaou, Louverture refused to round up enslaved women and children to sell to the Spanish. This feud also emphasized Louverture's inferior position in the trio of black generals in the minds of the Spanish – a check upon any ambitions for further promotion.[53]

On 29 April 1794, the Spanish garrison at Gonaïves was suddenly attacked by black troops fighting in the name of "the King of the French", who demanded that the garrison surrender. Approximately 150 men were killed and much of the populace forced to flee. White guardsmen in the surrounding area had been murdered, and Spanish patrols sent into the area never returned.[54] Louverture is suspected to have been behind this attack, although was not present. He wrote to the Spanish 5 May protesting his innocence – supported by the Spanish commander of the Gonaïves garrison, who noted that his signature was absent from the rebels' ultimatum. It was not until 18 May that Louverture would claim responsibility for the attack, when he was fighting under the banner of the French.[55]

The events at Gonaïves made Lleonart increasingly suspicious of Louverture. When they had met at his camp 23 April, the black general had shown up with 150 armed and mounted men, as opposed to the usual 25, choosing not to announce his arrival or waiting for permission to enter. Lleonart found him lacking his usual modesty or submission, and after accepting an invitation to dinner 29 April, Louverture afterward failed to show. The limp that had confined him to his bed during the Gonaïves attack was thought to be feigned and Lleonart suspected him of treachery.[56] Remaining distrustful of the black commander, Lleonart housed his wife and children whilst Louverture led an attack on Dondon in early May, an act which Lleonart later believed confirmed Louverture's decision to turn against the Spanish.[57]

Alliance with the French: 1794–1796

The timing of and motivation behind Louverture's volte-face against Spain remains debated among historians. C. L. R. James claimed that upon learning of the emancipation decree in May 1794, Louverture decided to join the French in June.[58] It is argued by Beaubrun Ardouin that Toussaint was indifferent toward black freedom, concerned primarily for his own safety and resentful over his treatment by the Spanish – leading him to officially join the French on 4 May 1794 when he raised the republican flag over Gonaïves.[59] Thomas Ott sees Louverture as "both a power-seeker and sincere abolitionist" who was working with Laveaux since January 1794 and switched sides on 6 May.[60]

Louverture claimed to have switched sides after emancipation was proclaimed and the commissioners Sonthonax and Polverel had returned to France in June 1794. However, a letter from Toussaint to General Laveaux confirms that he was already fighting officially on the behalf of the French by 18 May 1794.[61]

In the first weeks, Louverture eradicated all Spanish supporters from the Cordon de l'Ouest, which he had held on their behalf.[62] He faced attack from multiple sides. His former colleagues in the slave rebellion were now fighting against him for the Spanish. As a French commander, he was faced with British troops who had landed on Saint-Domingue in September, as the British hoped to take advantage of the ongoing instability to capture the prosperous island.[63] Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, who was Secretary of State for War for British prime minister William Pitt the Younger, instructed Sir Adam Williamson, the lieutenant-governor of Jamaica, to sign an agreement with representatives of the French colonists that promised to restore the ancien regime, slavery and discrimination against mixed-race colonists, a move that drew criticism from abolitionists William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson.[64][65]

On the other hand, Louverture was able to pool his 4,000 men with Laveaux's troops in joint actions.[66] By now his officers included men who were to remain important throughout the revolution: his brother Paul, his nephew Moïse Hyacinthe, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Henri Christophe.[67]

Before long, Louverture had put an end to the Spanish threat to French Saint-Domingue. In any case, the Treaty of Basel of July 1795 marked a formal end to hostilities between the two countries. Black leaders Jean-François and Biassou continued to fight against Louverture until November, when they left for Spain and Florida, respectively. At that point, most of their men joined Louverture's forces.[68] Louverture also made inroads against the British presence, but was unable to oust them from Saint-Marc. He contained them by resorting to guerilla tactics.[69]

Throughout 1795 and 1796, Louverture was also concerned with re-establishing agriculture and exports, and keeping the peace in areas under his control. In speeches and policy he revealed his belief that the long-term freedom of the people of Saint-Domingue depended on the economic viability of the colony.[70] He was held in general respect, and resorted to a mixture of diplomacy and force to return the field hands to the plantations as emancipated and paid workers.[71] Workers regularly staged small rebellions, protesting poor working conditions, their lack of real freedom, or their fear of a return to slavery. They wanted to establish their own small holdings and work for themselves, rather than on plantations.[72]

Another of Louverture's concerns was to manage potential rivals for power within the French part of the colony. The most serious of these was the mulatto commander Jean-Louis Villatte, based in Cap-Français. Louverture and Villate had competed over the command of some sections of troops and territory since 1794. Villatte was thought to be somewhat racist toward black soldiers such as Louverture and planned to ally with André Rigaud, a free man of color, after overthrowing French General Étienne Laveaux.[73] In 1796 Villate drummed up popular support by accusing the French authorities of plotting a return to slavery.

On 20 March, he succeeded in capturing the French Governor Laveaux, and appointed himself Governor. Louverture's troops soon arrived at Cap-Français to rescue the captured governor and to drive Villatte out of town. Louverture was noted for opening the warehouses to the public, proving that they were empty of the chains that residents feared had been imported to prepare for a return to slavery. He was promoted to commander of the West Province two months later, and in 1797 was appointed as Saint-Domingue's top-ranking officer.[74] Laveaux proclaimed Louverture as Lieutenant Governor, announcing at the same time that he would do nothing without his approval, to which Louverture replied: "After God, Laveaux."[75]

Third Commission: 1796–1797

A few weeks after Louverture's triumph over the Villate insurrection, France's representatives of the third commission arrived in Saint-Domingue. Among them was Sonthonax, the commissioner who had previously declared abolition of slavery on the same day as Louverture's proclamation of Camp Turel.[76] At first the relationship between the two men was positive. Sonthonax promoted Louverture to general and arranged for his sons, Placide and Isaac, who were eleven and fourteen respectively to attend a school in mainland France for the children of colonial officials .[77] This was done to provide them with a formal education in the French language and culture, one that Louverture highly desired for his children, but to also use them as political hostages against Louverture should he act against the will of the central French authority in Paris. In spite of this Placide and Isaac ran away enough times from the school that they were moved to the Collège de la Marche, a division of the old University of Paris. Here in Paris they would regularly dine with members of the French nobility such as Joséphine de Beauharnais, who would go on to become Empress of France as the wife of Napoleon Bonaparte.

In September 1796, elections were held to choose colonial representatives for the French national assembly. Louverture's letters show that he encouraged Laveaux to stand, and historians have speculated as to whether he was seeking to place a firm supporter in France or to remove a rival in power.[78] Sonthonax was also elected, either at Louverture's instigation or on his own initiative. While Laveaux left Saint-Domingue in October, Sonthonax remained.[79][80]Sonthonax, a fervent revolutionary and fierce supporter of racial equality, soon rivaled Louverture in popularity. Although their goals were similar, they had several points of conflict.[81][82] While Louverture was quoted as saying that "I am black, but I have the soul of a white man" in reference to his self-identification as a Frenchman, loyalty to the French nation, and Catholicism. Sonthonax, who had married a free black woman by this time, countered with "I am white, but I have the soul of a black man" in reference to his strong abolitionist and secular republican sentiments.[10] They strongly disagreed about accepting the return of the white planters who had fled Saint-Domingue at the start of the revolution. To the ideologically motivated Sonthonax, they were potential counter-revolutionaries who had fled the liberating force of the French Revolution and were forbidden from returning to the colony under pain of death. Louverture on the other hand saw them as wealth generators who could restore the commercial viability of the colony. The planters political and familial connections to Metropolitan France could also foster better diplomatic and economic ties to Europe.[83][10]

In summer 1797, Louverture authorized the return of Bayon de Libertat, the former overseer of the Bréda plantation, with whom he had shared a close relationship with ever since he was enslaved. Sonthonax wrote to Louverture threatening him with prosecution and ordering him to get de Libertat off the island. Louverture went over his head and wrote to the French Directoire directly for permission for de Libertat to stay.[84] Only a few weeks later, he began arranging for Sonthonax's return to France that summer.[74] Louverture had several reasons to want to get rid of Sonthonax; officially he said that Sonthonax had tried to involve him in a plot to make Saint-Domingue independent, starting with a massacre of the whites of the island.[85] The accusation played on Sonthonax's political radicalism and known hatred of the aristocratic grands blancs, but historians have varied as to how credible they consider it.[86][87]

On reaching France, Sonthonax countered by accusing Louverture of royalist, counter-revolutionary, and pro-independence tendencies.[88] Louverture knew that he had asserted his authority to such an extent that the French government might well suspect him of seeking independence.[89] At the same time, the French Directoire government was considerably less revolutionary than it had been. Suspicions began to brew that it might reconsider the abolition of slavery.[90] In November 1797, Louverture wrote again to the Directoire, assuring them of his loyalty, but reminding them firmly that abolition must be maintained.[91]

Treaties with Britain and the United States: 1798

For months, Louverture was in sole command of French Saint-Domingue, except for a semi-autonomous state in the south, where general André Rigaud had rejected the authority of the third commission.[92] Both generals continued harassing the British, whose position on Saint-Domingue was increasingly weak.[93] Louverture was negotiating their withdrawal when France's latest commissioner, Gabriel Hédouville, arrived in March 1798, with orders to undermine his authority.[94] Nearing the end of the revolution Louverture grew substantially wealthy; owning numerous slaves at Ennery, obtaining thirty-one properties, and earning almost 300,000 colonial livre per year from these properties.[95] As leader of the revolution, this accumulated wealth made Louverture the richest person on Saint-Domingue. Louverture's actions evoked a collective sense of worry among the European powers and the US, who feared that the success of the revolution would inspire slave revolts across the Caribbean, the South American colonies, and the southern United States.[96]

On 30 April 1798, Louverture signed a treaty with the British general Thomas Maitland, exchanging the withdrawal of British troops from western Saint-Domingue in return for a general amnesty for the French counter-revolutionaries in those areas. In May, Port-au-Prince was returned to French rule in an atmosphere of order and celebration.[97]

In July, Louverture and Rigaud met commissioner Hédouville together. Hoping to create a rivalry that would diminish Louverture's power, Hédouville displayed a strong preference for Rigaud, and an aversion to Louverture.[98] However, General Maitland was also playing on French rivalries and evaded Hédouville's authority to deal with Louverture directly.[99] In August, Louverture and Maitland signed treaties for the evacuation of the remaining British troops. On 31 August, they signed a secret treaty that lifted the British blockade on Saint-Domingue in exchange for a promise that Louverture would not attempt to cause unrest in British colonies in the West Indies.[100]

As Louverture's relationship with Hédouville reached the breaking point, an uprising began among the troops of his adopted nephew, Hyacinthe Moïse. Attempts by Hédouville to manage the situation made matters worse and Louverture declined to help him. As the rebellion grew to a full-scale insurrection, Hédouville prepared to leave the island, while Louverture and Dessalines threatened to arrest him as a troublemaker.[101] Hédouville sailed for France in October 1798, nominally transferring his authority to Rigaud. Louverture decided instead to work with Phillipe Roume, a member of the third commission who had been posted to the Spanish parts of the colony.[102] Although Louverture continued to protest his loyalty to the French government, he had expelled a second government representative from the territory and was about to negotiate another autonomous agreement with one of France's enemies.[103]

The United States had suspended trade with France in 1798 because of increasing tensions between the American and French governments over the issue of privateering. The two countries entered into the so-called "Quasi"-War, but trade between Saint-Domingue and the United States was desirable to both Louverture and the United States. With Hédouville gone, Louverture sent diplomat Joseph Bunel, a grand blanc former planter married to a Black Haitian wife, to negotiate with the administration of John Adams. Adams as a New Englander who was openly hostile to slavery was much more sympathetic to the Haitian cause than the Washington administration before and Jefferson after, both of whom came from Southern slave-owning planter backgrounds. The terms of the treaty were similar to those already established with the British, but Louverture continually rebuffed suggestions from either power that he should declare independence.[104] As long as France maintained the abolition of slavery, he appeared to be content to have the colony remain French, at least in name.[105]

Expansion of territory: 1799–1801

In 1799, the tensions between Louverture and Rigaud came to a head. Louverture accused Rigaud of trying to assassinate him to gain power over Saint-Domingue. Rigaud claimed Louverture was conspiring with the British to restore slavery.[106] The conflict was complicated by racial overtones that escalated tensions between full blacks and mulattoes.[107][108] Louverture had other political reasons for eliminating Rigaud; only by controlling every port could he hope to prevent a landing of French troops if necessary.[109]

After Rigaud sent troops to seize the border towns of Petit-Goave and Grand-Goave in June 1799, Louverture persuaded Roume to declare Rigaud a traitor and attacked the southern state.[110] The resulting civil war, known as the War of Knives, lasted more than a year, with the defeated Rigaud fleeing to Guadeloupe, then France, in August 1800.[111] Louverture delegated most of the campaign to his lieutenant, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who became infamous, during and after the war, for massacring mulatto captives and civilians.[112] The number of deaths is contested: the contemporary French general François Joseph Pamphile de Lacroix suggested 10,000 deaths, while the 20th-century Trinidadian historian C. L. R. James claimed there were only a few hundred deaths.[25][113]

In November 1799, during the civil war, Napoleon Bonaparte gained power in France and passed a new constitution declaring that the colonies would be subject to special laws.[114] Although the colonies suspected this meant the re-introduction of slavery, Napoleon began by confirming Louverture's position and promising to maintain abolition.[115] But he also forbade Louverture to invade Spanish Santo Domingo, an action that would put Louverture in a powerful defensive position.[116] Louverture was determined to proceed anyway and coerced Roume into supplying the necessary permission.[117] At the same time, in order to improve the political relationships with the other European powers, Louverture looked to further stabilize the political landscape of the Caribbean.[10] When Isaac Yeshurun Sasportas, a member of a prominent Sephardic Jewish family from Saint-Domingue, attempted to foment another slave revolt in neighboring British Jamaica, Louverture leaked the plot to the British. As a result Sasportas was captured and executed by the colonial authorities on December 23, 1799.[10][118][119]

In January 1801, Louverture and his nephew, General Hyacinthe Moïse invaded the Spanish territory, taking possession of it from the governor, Don Garcia, with few difficulties. The area had been less developed and populated than the French section. Louverture brought it under French law, abolishing slavery and embarking on a program of modernization. He now controlled the entire island.[120]

Constitution of 1801

.JPG.webp)

Napoleon had informed the inhabitants of Saint-Domingue that France would draw up a new constitution for its colonies, in which they would be subjected to special laws.[121] Despite his protestations to the contrary, the former slaves feared that he might restore slavery. In March 1801, Louverture appointed a constitutional assembly, composed chiefly of white planters, to draft a constitution for Saint-Domingue. He promulgated the Constitution on 7 July 1801, officially establishing his authority over the entire island of Hispaniola. It made him governor-general for life with near absolute powers and the possibility of choosing his successor. However, Louverture had not explicitly declared Saint-Domingue's independence, acknowledging in Article 1 that it was a single colony of the French Empire.[122] Article 3 of the constitution states: "There cannot exist slaves [in Saint-Domingue], servitude is therein forever abolished. All men are born, live and die free and French."[123] The constitution guaranteed equal opportunity and equal treatment under the law for all races, but confirmed Louverture's policies of forced labor and the importation of workers through the slave trade.[124] Identifying as a loyal Christian Frenchman, Louverture was not willing to compromise Catholicism for Vodou, the dominant faith among former slaves. Article 6 states that "the Catholic, Apostolic, Roman faith shall be the only publicly professed faith."[125] This strong preference for Catholicism went hand in hand with Louverture's self-identification of being a Frenchman, and his movement away from associating with Vodou and its origins in the practices of the plantation slaves from Africa.[126]

Louverture charged Colonel Charles Humbert Marie Vincent, who personally opposed the drafted constitution, with the task of delivering it to Napoleon. Several aspects of the constitution were damaging to France: the absence of provision for French government officials, the lack of trade advantages, and Louverture's breach of protocol in publishing the constitution before submitting it to the French government. Despite his disapproval, Vincent attempted to submit the constitution to Napoleon but was briefly exiled to the Mediterranean island of Elba for his pains.[127][note 3]

Louverture identified as a Frenchman and strove to convince Bonaparte of his loyalty. He wrote to Napoleon, but received no reply.[129] Napoleon eventually decided to send an expedition of 20,000 men to Saint-Domingue to restore French authority, and possibly, to restore slavery as well.[130] Given the fact that France had signed a temporary truce with Great Britain in the Treaty of Amiens, Napoleon was able to plan this operation without the risk of his ships being intercepted by the Royal Navy.

Leclerc's campaign: 1801–1802

.jpg.webp)

Napoleon's troops, under the command of his brother-in-law, General Charles Emmanuel Leclerc, were directed to seize control of the island by diplomatic means, proclaiming peaceful intentions, and keep secret his orders to deport all black officers.[131] Meanwhile, Louverture was preparing for defense and ensuring discipline. This may have contributed to a rebellion against forced labor led by his nephew and top general, Moïse, in October 1801. Because the activism was violently repressed, when the French ships arrived, not all of Saint-Domingue supported Louverture.[132] In late January 1802, while Leclerc sought permission to land at Cap-Français and Christophe held him off, the Vicomte de Rochambeau suddenly attacked Fort-Liberté, effectively quashing the diplomatic option.[133] Christophe had written to Leclerc: "you will only enter the city of Cap, after having watched it reduced to ashes. And even upon these ashes, I will fight you."

Louverture's plan in case of war was to burn the coastal cities and as much of the plains as possible, retreat with his troops into the inaccessible mountains, and wait for yellow fever to decimate the French.[134] The biggest impediment to this plan proved to be difficulty in internal communications. Christophe burned Cap-Français and retreated, but Paul Louverture was tricked by a false letter into allowing the French to occupy Santo Domingo. Other officers believed Napoleon's diplomatic proclamation, while some attempted resistance instead of burning and retreating.[135]

With both sides shocked by the violence of the initial fighting, Leclerc tried belatedly to revert to the diplomatic solution. Louverture's sons and their tutor had been sent from France to accompany the expedition with this end in mind and were now sent to present Napoleon's proclamation to Louverture.[136] When these talks broke down, months of inconclusive fighting followed.

This ended when Christophe, ostensibly convinced that Leclerc would not re-institute slavery, switched sides in return for retaining his generalship in the French military. General Jean-Jacques Dessalines did the same shortly later. On 6 May 1802, Louverture rode into Cap-Français and negotiated an acknowledgement of Leclerc's authority in return for an amnesty for him and his remaining generals. Louverture was then forced to capitulate and placed under house arrest on his property in Ennery.[137]

Arrest, imprisonment, and death: 1802–1803

Jean-Jacques Dessalines was at least partially responsible for Louverture's arrest, as asserted by several authors, including Louverture's son, Isaac. On 22 May 1802, after Dessalines learned that Louverture had failed to instruct a local rebel leader to lay down his arms per the recent ceasefire agreement, he immediately wrote to Leclerc to denounce Louverture's conduct as "extraordinary". For this action, Dessalines and his spouse received gifts from Jean Baptiste Brunet.[138]

Leclerc originally asked Dessalines to arrest Louverture, but he declined. Jean Baptiste Brunet was ordered to do so, but accounts differ as to how he accomplished this. One version said that Brunet pretended that he planned to settle in Saint-Domingue and was asking Louverture's advice about plantation management. Louverture's memoirs, however, suggest that Brunet's troops had been provocative, leading Louverture to seek a discussion with him. Either way, Louverture had a letter, in which Brunet described himself as a "sincere friend", to take with him to France. Embarrassed about his trickery, Brunet absented himself during the arrest.[139][140]

Finally on June 7, 1802, despite the promises made in exchange for his surrender, Toussaint Louverture – as well as a hundred members of his inner circle – were captured and deported to France. Brunet transported Louverture and his companions on the frigate Créole and the 74-gun Héros, claiming that he suspected the former leader of plotting another uprising. Upon boarding the Créole, Toussaint Louverture warned his captors that the rebels would not repeat his mistake, saying that, "In overthrowing me you have cut down in Saint Domingue only the trunk of the tree of liberty; it will spring up again from the roots, for they are numerous and they are deep."[141]

The ships reached France on 2 July 1802 and, on 25 August, Louverture was imprisoned at Fort-de-Joux in Doubs. During this time, Louverture wrote a memoir.[142] He died in prison on 7 April 1803 at the age of 59. Suggested causes of death include exhaustion, malnutrition, apoplexy, pneumonia, and possibly tuberculosis.[143][144]

Views and stances

Religion and spirituality

Throughout his life, Louverture was known as a devout Roman Catholic.[145] Having been baptized into the church as a slave by the Jesuits, Louverture would go on to be one of the few slaves on the Bréda plantation to be labeled devout. He celebrated Mass every day when possible, regularly served as godfather at multiple slave baptisms, and constantly quizzed others on the catechism of the church. In 1763 the Jesuits were expelled for spreading Catholicism among the slaves and undermining planter propaganda that slaves were mentally inferior. Toussaint would grow closer to the Capuchin Order that succeeded them in 1768, especially as they did not own plantations like the Jesuits. Louverture would also go on to have two formal Catholic weddings to both of his wives once freed. In his memoirs he fondly recounted the weekly ritual his family had on Sundays of going to church and enjoying a communal meal.[10]

After defeating forces led by André Rigaud in the War of the Knives, Louverture consolidated his power by decreeing a new constitution for the colony in 1801. It established Catholicism as the official religion.[125] Although Vodou was generally practiced on Saint-Domingue in combination with Catholicism, little is known for certain if Louverture had any connection with it. Officially as ruler of Saint-Domingue, he discouraged its practice and eventually persecuted its followers.[146]

Historians have suggested that he was a member of high degree of the Masonic Lodge of Saint-Domingue, mostly based on a Masonic symbol he used in his signature. The membership of several free blacks and white men close to him have been confirmed.[147]

Legacy

In his absence, Jean-Jacques Dessalines led the Haitian rebellion until its completion, finally defeating the French forces in 1803, two-thirds of the men had died when Napoleon withdrew his forces.

John Brown claimed influence by Louverture in his plans to invade Harpers Ferry. During the 19th century, African Americans referred to Louverture as an example of how to reach freedom.[148]

On 29 August 1954, the Haitian ambassador to France, Léon Thébaud, inaugurated a stone cross memorial for Toussaint Louverture at the foot of Fort de Joux.[149] Years afterward, the French government ceremoniously presented a shovelful of soil from the grounds of Fort de Joux to the Haitian government as a symbolic transfer of Louverture's remains. An inscription in his memory was installed in 1998 on the wall of the Panthéon in Paris.[150]

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Up to, for example, C. L. R. James, writing in 1938.

- ↑ The wording of the proclamation issued by then rebel slave leader Louverture in August 1793, which may have been the first time he publicly used the name "Louverture", possibly refer to an anti-slavery passage in Abbé Raynal's A Philosophical and Political History of the Settlements and Trade of the Europeans in the East and West Indies.[26][27]

- ↑ Napoleon himself would later be exiled to Elba after his 1814 abdication.[128]

References and citations

- ↑ Fombrun, Odette Roy, ed. (2009). "History of The Haitian Flag of Independence" (PDF). The Flag Heritage Foundation Monograph And Translation Series Publication No. 3. p. 13. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ "Toussaint l'Ouverture". Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Pearson, 2023.

- ↑ Chartrand, René (1996). Napoleon's Overseas Army (3rd ed.). Hong Kong: Reed International Books Ltd. ISBN 0-85045-900-1.

- ↑ White, Ashli (2010). Encountering Revolution: Haiti and the Making of the Early Republic. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8018-9415-2.

- ↑ Lamrani, Salim (30 April 2021). "Toussaint Louverture, In the Name of Dignity. A Look at the Trajectory of the Precursor of Independence of Haiti". Études caribéennes (48). doi:10.4000/etudescaribeennes.22675. ISSN 1779-0980. S2CID 245041866.

- ↑ Marcus Rainsford (2013). An Historical Account of the Black Empire of Hayti. Duke University Press. p. 310.

- ↑ John P. McKay; Bennett D. Hill; John Buckler; Clare Haru Crowston; Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks; Joe Perry (2011). Understanding Western Society, Combined Volume: A Brief History. Macmillan. p. 608.

- ↑ Jeff Fleischer (2019). Rockin' the Boat: 50 Iconic Revolutionaries — From Joan of Arc to Malcom X. Zest Books. p. 224.

- ↑ Vulliamy, Ed, ed. (28 August 2010). "The 10 best revolutionaries". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Girard, Philippe (2016). Toussaint Louverture: A Revolutionary Life. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465094134.

- ↑ Cauna, pp. 7–8

- ↑ Popkin, Jeremy D. (2012). A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution. John Wiley & Sons. p. 114. ISBN 978-1405198219.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 59–60, 62.

- ↑ Forsdick & Høgsbjerg (2017), p. 14.

- ↑ Korngold, Ralph [1944], 1979. Citizen Toussaint. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313207941.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 60, 62.

- 1 2 Beard, John Relly. [1863] 2001. Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography (online ed.). Boston: James Redpath.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 66, 70, 72.

- 1 2 3 4 5 de Cauna, Jacques. 2004. Toussaint L'Ouverture et l'indépendance d'Haïti: Témoignages pour une commémoration. Paris: Ed. Karthala.

- 1 2 Cauna, pp. 63–65.

- ↑ Cauna, Jacques de (2012). "Dessalines esclave de Toussaint ?". Outre-Mers. Revue d'histoire. 99 (374): 319–322. doi:10.3406/outre.2012.4936.

- 1 2 Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 62.

- ↑ Lee, Eunice Day (November 1951). "Toussaint Louverture". Negro History Bulletin. 15 (2): 40–39. JSTOR 44212502.

- 1 2 3 4 Bell (2008) [2007], p. 61.

- 1 2 Bell (2008) [2007], p. 18.

- ↑ Blackburn (2011), p. 54.

- ↑ Bell, 2007, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 60, 80.

- ↑ James (1814), p. 104.

- ↑ Richard J. Callahan (2008). New Territories, New Perspectives: The Religious Impact of the Louisiana Purchase. University of Missouri Press. p. 158.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 23–24.

- ↑ James (1814), p. 90.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 33.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 42–50.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 46.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 50.

- ↑ Langley, Lester (1996). The Americas in the Age of Revolution: 1750–1850. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0300066135.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 56.

- ↑ James (1814), pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 86–87.

- ↑ James (1814), p. 107.

- ↑ David Geggus (ed.), Haitian Revolutionary Studies. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 54.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 19.

- ↑ James, pp. 128–130

- ↑ James (1814), p. 137.

- ↑ James (1814), pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 92–95.

- ↑ Charles Forsdick and Christian Høgsbjerg, Toussaint Louverture: A Black Jacobin in the Age of Revolutions. London: Pluto Press, 2017, p. 55.

- ↑ Geggus (ed.), Haitian Revolutionary Studies, pp. 120–129.

- ↑ Geggus (ed.), Haitian Revolutionary Studies, p. 122.

- ↑ Geggus (ed.), Haitian Revolutionary Studies, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Ada Ferrer, Freedom's Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolutions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 2014, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Ferrer. Freedom's Mirror, p. 119.

- ↑ James, The Black Jacobins, pp. 143–144.

- ↑ Beaubrun Ardouin, Études sur l'Histoire d'Haïti. Port-au-PrinceL Dalencour, 1958, pp. 2:86–93.

- ↑ Thomas Ott, The Haitian Revolution, 1789–1804. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1973, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Geggus (ed.), Haitian Revolutionary Studies, pp. 120–122.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 104–108.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 109.

- ↑ C. L. R. James, Black Jacobins (London: Penguin, 1938), p. 109.

- ↑ David Geggus, Slavery, War and Revolution: The British Occupation of Saint Domingue, 1793–1798 (New York: Clarendon Press, 1982).

- ↑ James, p. 143

- ↑ James, p. 147.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 115.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 110–114.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 113, 126.

- ↑ James, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ James, pp. 152–154.

- ↑ Laurent Dubois and John Garrigus, Slave Revolution in the Caribbean, 1789–1804: A Brief History with Documents. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 31.

- 1 2 Dubois and Garrigus, p. 31.

- ↑ Bell, pp. 132–134; James, pp. 163–173.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 136.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 137, 140–141.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 145.

- ↑ James (1814), p. 180.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 141–142, 147.

- ↑ James (1814), pp. 174–176.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 145–146.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 150.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 150–153.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 153–154.

- ↑ James (1814), p. 190.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 153.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 153, 155

- ↑ James (1814), p. 179.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 155.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 142–143.

- ↑ James (1814), p. 201.

- ↑ James (1814), pp. 201–202.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Meade, Teresa (2016). A History of Modern Latin America: 1800 to the Present. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 68. ISBN 978-1118772485.

- ↑ James (1814), pp. 202, 204.

- ↑ James (1814), pp. 207–208.

- ↑ James (1814), pp. 211–212.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 159–160.

- ↑ James (1814), pp. 219–220.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 165–166.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Philippe Girard, "Black Talleyrand: Toussaint L'Ouverture's Secret Diplomacy with England and the United States", William and Mary Quarterly 66:1 (January 2009), 87–124.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 173–174.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 175–77, 178–79.

- ↑ James (1814), pp. 229–230.

- ↑ James (1814), pp. 224, 237.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 177.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 182–185.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 179–180.

- ↑ James (1814), pp. 236–237.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 180.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 184.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 186.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 180–182, 187.

- ↑ LOKER, ZVI (1981). "An eighteenth-century plan to invade Jamaica; Isaac Yeshurun Sasportas – French patriot or Jewish radical idealist?". Transactions & Miscellanies (Jewish Historical Society of England). 28: 132–1144. ISSN 0962-9688. JSTOR 29778924.

- ↑ Girard, Philippe (1 July 2020). "Isaac Sasportas, the 1799 Slave Conspiracy in Jamaica, and Sephardic Ties to the Haitian Revolution". Jewish History. 33 (3): 403–435. doi:10.1007/s10835-020-09358-z. ISSN 1572-8579. S2CID 220510628.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 189–191.

- ↑ Alexis, Stephen, Black Liberator, London: Ernest Benn Limited, 1949, p. 165.

- ↑ "Constitution de la colonie français de Saint-Domingue", Le Cap, 1801

- ↑ Ogé, Jean-Louis. Toussaint L'Ouverture et l'Indépendence d'Haïti. Brossard: L’Éditeur de Vos Rêves, 2002, p. 140.

- ↑ Bell, pp. 210–211.

- 1 2 "Haitian Constitution of 1801 (English) – TLP". thelouvertureproject.org. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ↑ Ogé, Jean-Louis. Toussaint L'Ouverture et l'Indépendence d'Haïti. Brossard: L’Éditeur de Vos Rêves, 2002, p. 141.

- ↑ Philippe Girard, The Slaves Who Defeated Napoléon: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the Haitian War of Independence (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, November 2011).

- ↑ Latson, Jennifer (26 February 2015). "Why Napoleon Probably Should Have Just Stayed in Exile the First Time". Time. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ↑ James (1814), p. 263.

- ↑ Philippe Girard, "Napoléon Bonaparte and the Emancipation Issue in Saint-Domingue, 1799–1803," French Historical Studies 32:4 (Fall 2009), 587–618.

- ↑ James, pp. 292–294; Bell, pp. 223–224

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 206–209, 226–229, 250

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 232–234.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 234–236.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 234, 236–237.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 237–241.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 261–262.

- ↑ Girard, Philippe R. (July 2012). "Jean-Jacques Dessalines and the Atlantic System: A Reappraisal" (PDF). The William and Mary Quarterly. Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture. 69 (3): 559. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.69.3.0549. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

a list of "extraordinary expenses incurred by General Brunet in regards to [the arrest of] Toussaint" started with "gifts in wine and liquor, gifts to Dessalines and his spouse, money to his officers: 4000 francs."

- ↑ Girard, Philippe R. (2011). The Slaves who Defeated Napoléon: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian War of Independence, 1801–1804. University of Alabama Press.

- ↑ Oruno D. Lara, «Toussaint Louverture François Dominique Toussaint dit 1743–1803 », Encyclopædia Universalis, 7 avril 2021

- ↑ Abbott, Elizabeth (1988). Haiti: An Insider's History of the Rise and Fall of the Duvaliers, Simon & Schuster. p. viii ISBN 0671686208.

- ↑ Forsdick & Høgsbjerg (2017), p. 19.

- ↑ "John Bigelow: The last days of Toussaint Louverture". faculty.webster.edu.

- ↑ Pike, Tim. "Toussaint Louverture: helping Bordeaux come to terms with its slave trade past" (part 1) ~ Invisible Bordeaux website

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 194.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], pp. 56, 196.

- ↑ Bell (2008) [2007], p. 63.

- ↑ Clavin, Matthew (2008). "A Second Haitian Revolution". Civil War History. liv (2).

- ↑ Yacou, Alain, ed. (2007). "Vie et mort du général Toussaint-Louverture selon les dossiers conservés au Service Historique de la Défense, Château de Vincennes". Saint-Domingue espagnol et la révolution nègre d'Haïti (in French). Karthala Editions. p. 346. ISBN 978-2811141516. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ↑ le Cadet, Nicolas (21 October 2010). "Le portrait du juge idéal selon Noël du Fail dans les Contes et Discours d'Eutrapel". Centre d’Études et de Recherche Éditer/Interpréter (in French). University of Rouen. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

Works cited

- Alexis, Stephen. 1949. Black Liberator: The Life of Toussaint Louverture. London: Ernest Benn.

- Ardouin, Beaubrun. 1958. Études sur l'Histoire d'Haïti. Port-au-Prince: Dalencour.

- Beard, John Relly. 1853. The Life of Toussaint L'Ouverture: The Negro Patriot of Hayti. ISBN 1587420104

- — [1863] 2001. Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography (online ed.). Boston: James Redpath. – Consists of the earlier "Life", supplemented by an autobiography of Toussaint written by himself.

- Bell, Madison Smartt (2008) [2007]. Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1400079353.

- Blackburn, Robin (2011). The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery 1776–1848. Verso Books. ISBN 978-1844674756.

- de Cauna, Jacques. 2004. Toussaint L'Ouverture et l'indépendance d'Haïti. Témoignages pour une commémoration. Paris: Ed. Karthala.

- Cesaire, Aimé. 1981. Toussaint L'Ouverture. Paris: Présence Africaine. ISBN 2708703978.

- Davis, David Brion. 31 May 2007. "He changed the New World." The New York Review of Books. pp. 54–58 – Review of M. S. Bell's Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography.

- Dubois, Laurent, and John D. Garrigus. 2006. Slave Revolution in the Caribbean, 1789–1804: A Brief History with Documents. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 031241501X.

- DuPuy, Alex. 1989. Haiti in the World Economy: Class, Race, and Underdevelopment since 1700. Westview Press. ISBN 0813373484.

- Ferrer, Ada. 2014. Freedom's Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107697782

- Foix, Alain. 2007. Toussaint L'Ouverture. Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

- — 2008. Noir de Toussaint L'Ouverture à Barack Obama. Paris: Ed. Galaade.

- Forsdick, Charles, and Christian Høgsbjerg, eds. 2017. The Black Jacobins Reader. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- — 2017. Toussaint Louverture: A Black Jacobin in the Age of Revolutions. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0745335148.

- Geggus, David, ed. 2002. Haitian Revolutionary Studies. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253341044.

- Girard, Philippe. 2009. "Black Talleyrand: Toussaint L'Ouverture's Secret Diplomacy with England and the United States". William and Mary Quarterly 66(1):87–124.

- — 2009. "Napoléon Bonaparte and the Emancipation Issue in Saint-Domingue, 1799–1803". French Historical Studies 32(4):587–618.

- — 2011. The Slaves who Defeated Napoléon: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the Haitian War of Independence, 1801–1804. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0817317325.

- — 2012. "Jean-Jacques Dessalines and the Atlantic System: A Reappraisal". William and Mary Quarterly.

- — 2016. Toussaint Louverture: A Revolutionary Life. New York: Basic Books.

- Graham, Harry. 1913. "The Napoleon of San Domingo", The Dublin Review 153:87–110.

- Heinl, Robert, and Nancy Heinl. 1978. Written in Blood: The story of the Haitian people, 1492–1971. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0395263050.

- Hunt, Alfred N. 1988. Haiti's Influence on Antebellum America: Slumbering Volcano in the Caribbean. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0807131970.

- James, C. L. R. [1934] 2013. Toussaint L'Ouverture: The story of the only successful slave revolt in history: A Play in Three Acts. Duke University Press.

- — [1963] 2001. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. Penguin Books. ISBN 0140299815.

- Johnson, Ronald Angelo. 2014. Diplomacy in Black and White: John Adams, Toussaint Louverture, and Their Atlantic World Alliance. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- Joseph, Celucien L. 2012. Race, Religion, and The Haitian Revolution: Essays on Faith, Freedom, and Decolonization. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- — 2013. From Toussaint to Price-Mars: Rhetoric, Race, and Religion in Haitian Thought. CreateSpace Independent Publishing.

- Korngold, Ralph. [1944] 1979. Citizen Toussaint. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313207941.

- de Lacroix, F. J. Pamphile. [1819] 1995. La révolution d'Haïti.

- Norton, Graham Gendall. April 2003. "Toussaint L'Ouverture." History Today.

- Ott, Thomas. 1973. The Haitian Revolution: 1789–1804. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0870495453

- Parkinson, Wenda. 1978. 'This Gilded African': Toussaint L'Ouverture. Quartet Books.

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. 2006. Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 0313332711.

- Ros, Martin. [1991] 1994. The Night of Fire: The Black Napoleon and the Battle for Haiti (in Dutch). New York; Sarpedon. ISBN 0962761370.

- Schlesinger Jr., Arthur M. World leaders, past & present – Toussaint L'ouverture.

- Schœlcher, Victor. 1889. Vie de Toussaint-L'Ouverture.

- Stinchcombe, Arthur L. 1995. Sugar Island Slavery in the Age of Enlightenment: The Political Economy of the Caribbean World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1400807778

- The Collective Works of Yves. ISBN 1401083080

- Book I explains Haiti's past to be recognized.

- Book 2 culminates Haiti's scared present day epic history.

- Thomson, Ian. 1992. Bonjour Blanc: A Journey Through Haiti. London. ISBN 0099452154.

- L'Ouverture, Toussaint. 2008. The Haitian Revolution, with an introduction by J. Aristide. New York: Verso – A collection of L'Ouverture's writings and speeches. ISBN 1844672611.

- Tyson, George F., ed. 1973. Great Lives Considered: Toussaint L'Ouverture. Prentice Hall. ISBN 013925529X – A compilation, includes some of Toussaint's writings.

- James, Stephen (1814). The History of Toussaint Louverture. J. Butterworth and Son.

- Forsdick, Charles; Høgsbjerg, Christian (2017). Toussaint Louverture: A Black Jacobin in the Age of Revolutions. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0745335148. JSTOR j.ctt1pv89b9.6.

External links

- Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography by J. R. Beard, 1863

- Toussaint L'Ouverture, a Santana Latin rock song from their first album, Santana.

- A section of Bob Corbett's on-line course on the history of Haïti that deals with Toussaint's rise to power.

- The Louverture Project

- Toussaint at IMDb

- "Égalité for All: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution" Archived 30 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Noland Walker. PBS documentary. 2009.

- Spencer Napoleonica Collection Archived 5 December 2012 at archive.today at Newberry Library

- Black Spartacus Archived 3 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine by Anthony Maddalena (Thee Black Swan Theatre Company); a radio play in four parts which tells the story of Toussaint L'Ouverture and the Haitian Slave Uprising of 1791–1803

- Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution by Paul Foot (Redwords, 2021) (publication of two lectures from 1978 and 1991)

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1889.

- Elliott, Charles Wyllys. St. Domingo, its revolution and its hero, Toussaint Louverture, New York, J. A. Dix, 1855. Manioc

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Toussaint L'Ouverture by Wendell Phillips (hardcover edition, published in English, French and Kreyòl Ayisyen).