The Tonkinese Rifles (tirailleurs tonkinois) were a corps of Tonkinese light infantrymen raised in 1884 to support the operations of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps. Led by French officers seconded from the marine infantry, Tonkinese riflemen fought in several engagements against the Chinese during the Sino-French War and took part in expeditions against Vietnamese insurgents during the subsequent French Pacification of Tonkin. The French also organized similar units of indigenous riflemen from Annam and Cambodia. All three categories of indigenous soldiers were known in Vietnam as Lính tập.

Background

During the campaigns of Francis Garnier in Tonkin in 1873 the French raised irregular units of Tonkinese militiamen, many of them Christians who felt little loyalty to the brutal regime of Tự Đức. These units existed for only a few weeks, and were disbanded when the French withdrew from Tonkin in the spring of 1874, but the experiment demonstrated the potential for the recruitment of auxiliary soldiers in Tonkin.

The employment of Vietnamese auxiliaries on a regular basis was pioneered in Cochinchina, where the French formed a regiment of Annamese riflemen in 1879 (variously referred to as tirailleurs annamites, tirailleurs saigonais or tirailleurs cochinchinois).[1]

Between 1883 and 1885 the French were heavily engaged in Tonkin against the Black Flag Army and Vietnamese and Chinese forces. The successive commanders of the Tonkin Expeditionary Corps all made use of Tonkinese auxiliaries in one form or another. The establishment of regular regiments of tirailleurs tonkinois in 1884 was preceded by experiments with native auxiliaries in Tonkin by General Bouët and Admiral Courbet in the second half of 1883. The French employed several hundred Yellow Flags as auxiliaries against the Black Flag Army in the battles of August 1883. The Yellow Flags, under the command of a Greek adventurer named Georges Vlavianos who had taken part in Francis Garnier's Tonkin campaign in 1873, fought competently enough in a skirmishing role in the Battle of Phủ Hoài (15 August 1883) and the Battle of Palan (1 September 1883), but were paid off shortly after the latter engagement because of their undisciplined behaviour.

The French expeditionary column commanded by Admiral Amédée Courbet in the Sơn Tây Campaign included four companies of Annamese riflemen from Cochinchina, each attached to a marine infantry battalion. It also included a separate unit of 800 Tonkinese auxiliaries, already called tirailleurs tonkinois, under the command of chef de bataillon Bertaux-Levillain. Many of these Tonkinese auxiliaries were men who had fought with Vlavianos in the autumn battles, who managed to re-enlist in French service after the Yellow Flag battalion was disbanded. Courbet was unable to give these Tonkinese auxiliaries French company captains, and they played little part in the fighting at Phu Sa on 14 December and Son Tay on 16 December. The Annamese riflemen, by contrast, fighting under the command of French officers, distinguished themselves at the capture of the Phu Sa entrenchments.

General Charles-Théodore Millot, who succeeded Admiral Courbet as commander of the Tonkin expeditionary corps in February 1884, was a firm believer in the utility of native auxiliaries. Millot believed that if native formations were given a sufficient number of French officers and NCOs, they would be far more effective in action and less prone to the indiscipline shown by the Yellow Flags. To test his theory, he organised Bertaux-Levillain's Tonkinese auxiliaries into regular companies, each under the command of a marine infantry captain. Several companies of Tonkinese riflemen took part in the Bắc Ninh Campaign (March 1884) and the Hưng Hóa expedition (April 1884), and in May 1884 the expeditionary corps included 1,500 Tonkinese auxiliaries.[2]

Establishment and organization

Encouraged by the performance of his Tonkinese auxiliaries in the campaigns of March and April 1884, Millot decided to formalise their status by creating two regiments of Tonkinese tirailleurs, each of 3,000 men, organised into three battalions of four 250-man companies and led by experienced marine infantry officers. This model had been used several years earlier in Cochinchina for the Annamese Rifle Regiment. By a decree of 12 May 1884, Millot established the 1st and 2nd Tonkinese Rifle Regiments. The two regiments were commanded respectively by Lieutenant-Colonel de Maussion and Lieutenant-Colonel Berger, two veteran officers who had distinguished themselves in Bouët and Courbet's campaigns, and their six constituent battalions were commanded by chefs de bataillon Tonnot, Jorna de Lacale, Lafont, Merlaud, Pelletier and Pizon.[3]

Due to an initial shortage of qualified marine infantry officers the two regiments were not constituted at their full strength immediately. For some months they included only nine companies, organised into two battalions.[4] However, recruitment continued throughout the summer of 1884 and by 30 October both regiments had reached their full strength of 3,000 men.[5]

One expedient adopted by General Millot to speed recruitment was to make use of deserters from the Black Flag Army. Several hundred Black Flag soldiers surrendered in July 1884, in the wake of the French capture of Hưng Hóa and Tuyên Quang, and offered their services to the French. General Millot allowed them to join one of the Tonkinese Rifle regiments as a separate company, and they were sent to an isolated French post on the Day River and placed under the command of a sympathetic French marine infantry officer, Lieutenant Bohin. Many French officers were appalled at Millot's willingness to trust the Black Flags, and Bohin was henceforth christened le condamné à mort. In fact the Black Flags responded well to his kind treatment and for several months gave good service, taking part in a number of sweeps against Vietnamese insurgents and bandits. However, during the night of 25 December 1884 they deserted en masse with their weapons, uniforms and equipment and made off towards the Black River. They killed a Tonkinese sergeant to prevent him from giving the alarm, but left Bohin sleeping peacefully in his bed. It seems likely that, impressed by the advance of the Chinese armies in Tonkin, they had lost faith in a French victory and decided to rejoin the Black Flag Army, then taking part in the Siege of Tuyên Quang. Millot's unfortunate experiment was not repeated by his successor General Brière de l'Isle, and no further attempts were made by the French to integrate Black Flag soldiers into the Tonkinese rifle regiments.

A third Tonkinese Rifle regiment was established by General de Courcy, by a decree of 28 July 1885, and a fourth by General Warnet, by a decree of 19 February 1886.[6]

Active service, Sino-French War

The 8th Company, 1st Tonkinese Rifle Regiment (Captain Dia, Lieutenant Goullet) formed part of the French column that captured Tuyen Quang on 2 June 1884.[7] The company also took part in Duchesne's expedition to relieve Tuyên Quang in November 1884, seeing action at the Battle of Yu Oc.[8] Thereafter, as part of the Tuyên Quang garrison, it fought with distinction alongside two companies of the French Foreign Legion in the Siege of Tuyên Quang (November 1884 to March 1885).[9]

The 12th Company, 1st Tonkinese Rifle Regiment (Captain Bouchet, Lieutenants Delmotte and Bataille) was engaged at Bắc Lệ (23 and 24 June 1884) and at the Battle of Lam (6 October 1884) during the Kep Campaign. Lieutenant Bataille was seriously wounded during the engagement at Lam and his men, leaderless, fell back before an advancing Chinese column. Their retreat left a serious gap in the centre of the French line, which was only filled by the fortuitous arrival of a line infantry company. Later in the battle the French counterattacked, and Bataille's Tonkinese took part in the final advance.[10]

The 1st Company, 1st Tonkinese Rifle Regiment (Captain de Beauquesne) took part in the Battle of Núi Bop (4 January 1885).[11]

The 1st Battalion, 1st Tonkinese Rifle Regiment (chef de bataillon Jorna de Lacale) and the 1st Battalion, 2nd Tonkinese Rifle Regiment (chef de bataillon Tonnot) took part in the Lạng Sơn Campaign (February 1885). Tonnot's battalion was heavily engaged at the Battle of Bac Vie (12 February 1885).[12]

The 1st Company, 2nd Tonkinese Rifle Regiment (Captain Geil) was engaged at the Battle of Đồng Đăng (23 February 1885).[13]

The 7th Company, 1st Tonkinese Rifle Regiment (Captain Granier, 2nd Lieutenant Donnat) scouted the Chinese trenches at the start of the Battle of Hòa Mộc (2 March 1885), suffering heavy casualties from the initial Chinese volley. 2nd Lieutenant Donnat was wounded in this engagement.[14]

Lieutenant Fayn's platoon of Captain Dufoulon's 1st Company, 1st Tonkinese Rifle Regiment, 50 men strong, routed a force of 400 Chinese, Vietnamese and Muong bandits at Thai That near Sơn Tây on 18 April 1885. The engagement took place four days after a ceasefire between the French and Chinese armies in Tonkin had come into effect in consequence of the conclusion of preliminaries of peace between France and China on 4 April. The prowess displayed by the Tonkinese riflemen on this occasion was given wide publicity by the French military authorities, and commemorated by General Brière de l'Isle in an order of the day issued on 26 April.[15]

Subsequent history 1890–1945

During the 1890s and early 1900s the Indo-Chinese tirailleurs saw on-going service against pirates and bandits within the boundaries of present-day Vietnam. Because of unwarranted doubts about their reliability the Tonkinese units were normally accompanied by detachments of French Colonial Infantry or Foreign Legionaires.[16] A fifth regiment of Tonkinese Rifles (5th R.T.T.) was raised in 1902 but was disbanded in 1908.

On the outbreak of World War I many of the French officers and non-commissioned officers of the tirailleurs tonkinois and tirailleurs annamite were recalled to France. One battalion of Tonkinese riflemen (6th B.T.I.) subsequently saw service on the Western Front near Verdun.[17]

In 1915 a battalion of the 3rd Regiment of Tonkinese Rifles (3rd R.T.T.) was sent to China to garrison the French Concession in Shanghai. The tirailleurs remaining in Indo-China saw service in 1917 in putting down a mutiny of the Garde Indignene (native gendarmerie) in Thai Nguyen. In August 1918 three companies of tirailleurs tonkinois formed part of a battalion of French Colonial Infantry sent to Siberia as part of the Allied intervention following the Russian Revolution.[18]

The four regiments of Tonkinese Rifles continued in existence between the two World Wars, seeing active service in Indochina, Syria (1920–21), Morocco (1925–26) and in the frontier clashes with Thailand (1940–41). Part of the 4th R.T.T. stationed at Yên Bái mutinied on 9 February 1930 but were suppressed by loyal troops from the same unit. All six of the Tonkinese and Annamite Rifle regiments were disbanded following the Japanese coup of 9 March 1945 against the French colonial administration of Indochina. Although large numbers of Vietnamese served with French Union Forces during the subsequent French Indochina War of 1946–54, they were incorporated in other units and the Indochinese tirailleur regiments were not re-established.[19] The last Indochinese unit in the French Army was the Far East Commando (Le Commando d'Extreme-Orient), which numbered about 200 Vietnamese, Montagnards, Khmers and Nùngs and saw active service in Algeria from 1956 until disbandment in June 1960.[20]

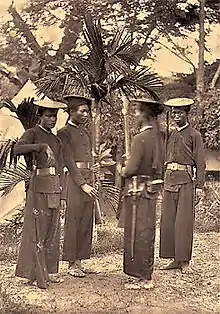

Uniforms

Until World War I the Tonkinese Rifle regiments wore uniforms closely modeled on indigenous dress (see photographs above). These included a flat salacco headdress of varnished bamboo, red sashes and head-scarves. The loose fitting tunics and trousers were usually of blue/black cotton, although a khaki version was adopted for field dress after 1900. The tirailleurs annamite wore the same uniform, with minor differences of insignia and with additional white clothing for summer wear. In 1912 a conical version of the salacco with a spiked top was adopted by all tirailleur units. This was worn until replaced by a pith helmet in 1931. During the same period the tirailleur uniforms were modified to conform with the standard khaki drill of the French Colonial Infantry, and the distinctive indigenous features disappeared.[21]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 86

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 188

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 86

- ↑ Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 86

- ↑ Mounier-Kuhn, 66

- ↑ Huard, 971 and 972

- ↑ Nicolas, 384

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 144

- ↑ Thomazi, Conquête, 237–41

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 60–61

- ↑ Nicolas, 362

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 288–98

- ↑ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 337–49; Nicolas, 382

- ↑ Nicolas, 402

- ↑ Huard, 757–8 and 970

- ↑ Maurice Rives, page 34 Les Linh Tap, ISBN 2-7025-0436-1

- ↑ Rives pages 50-52

- ↑ Rives pages 53-54

- ↑ Charles Lavauzelle Les Troupes de Marine ISBN 2-7025-0142-7

- ↑ Rives pages 125-127

- ↑ Rives pages 53-54 and 79-92

References

- Chartrand, René (2018). French Naval & Colonial Troops 1872–1914. Men-at-Arms. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-47-282619-0.

- Crocé, Eliane; et al. (1986). Les Troupes de Marine 1622 - 1984 (in French) (1st ed.). Limoges: Charles Lavauzelle. ISBN 2-7025-0142-7.

- Huard, L., La guerre du Tonkin (Paris, 1887)

- Lecomte, J., Lang-Son: combats, retraite et négociations (Paris, 1895)

- Lecomte, J., La vie militaire au Tonkin (Paris, 1893)

- Lecomte, J., Le guet-apens de Bac-Lé (Paris, 1890)

- Mounier-Kuhn, A., Les services de santé militaires français pendant la conquête du Tonkin et de l’Annam (1882–1896) (Paris, 2005)

- Nicolas, V., Livre d'or de l'infanterie de la marine (Paris, 1891)

- Thomazi, A., Histoire militaire de l’Indochine française (Hanoi, 1931)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)

.svg.png.webp)

_B%E1%BA%A3o_%C4%90%E1%BA%A1i_(%E4%BF%9D%E5%A4%A7).svg.png.webp)

.png.webp)