| Tomato | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Solanaceae |

| Genus: | Solanum |

| Species: | S. lycopersicum |

| Binomial name | |

| Solanum lycopersicum | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

The tomato (/təmeɪtoʊ/ or /təmɑːtoʊ/) is the edible berry of the plant Solanum lycopersicum,[1][2] commonly known as the tomato plant. The species originated in western South America, Mexico, and Central America.[2][3] The Nahuatl word tomatl gave rise to the Spanish word tomate, from which the English word tomato derived.[3][4] Its domestication and use as a cultivated food may have originated with the indigenous peoples of Mexico.[2][5] The Aztecs used tomatoes in their cooking at the time of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, and after the Spanish encountered the tomato for the first time after their contact with the Aztecs, they brought the plant to Europe, in a widespread transfer of plants known as the Columbian exchange. From there, the tomato was introduced to other parts of the European-colonized world during the 16th century.[2]

Tomatoes are a significant source of umami flavor.[6] They are consumed in diverse ways: raw or cooked, and in many dishes, sauces, salads, and drinks. While tomatoes are fruits—botanically classified as berries—they are commonly used culinarily as a vegetable ingredient or side dish.[3]

Numerous varieties of the tomato plant are widely grown in temperate climates across the world, with greenhouses allowing for the production of tomatoes throughout all seasons of the year. Tomato plants typically grow to 1–3 meters (3–10 ft) in height. They are vines that have a weak stem that sprawls and typically needs support.[2] Indeterminate tomato plants are perennials in their native habitat, but are cultivated as annuals. (Determinate, or bush, plants are annuals that stop growing at a certain height and produce a crop all at once.) The size of the tomato varies according to the cultivar, with a range of 1–10 cm (1⁄2–4 in) in width.[2]

History

The wild ancestor of the tomato, Solanum pimpinellifolium, is native to western South America.[7] These wild versions were the size of peas.[7] The first evidence of domestication points to the Aztecs and other peoples in Mesoamerica, who used the fruit fresh and in their cooking. The Spanish first introduced tomatoes to Europe, where they became used in Spanish food. In France, Italy and northern Europe, the tomato was initially grown as an ornamental plant. It was regarded with suspicion as a food because botanists recognized it as a nightshade, a relative of the poisonous belladonna.[3] This was exacerbated by the interaction of the tomato's acidic juice with pewter plates.[8] The leaves and fruit contain tomatine, which in large quantities would be toxic. However, the ripe fruit contains a much lower amount of tomatine than the immature fruit.[9]

Mesoamerica

The exact date of domestication is unknown; by 500 BC, it was already being cultivated in southern Mexico and probably other areas.[10]: 13 The Pueblo people are thought to have believed that those who witnessed the ingestion of tomato seeds were blessed with powers of divination.[11] The large, lumpy variety of tomato, a mutation from a smoother, smaller fruit, originated in Mesoamerica, and may be the direct ancestor of some modern cultivated tomatoes.[10]: 15

The Aztecs raised several varieties of tomato, with red tomatoes called xitomatl and green tomatoes (physalis) called tomatl (tomatillo).[12] Bernardino de Sahagún reported seeing a great variety of tomatoes in the Aztec market at Tenochtitlán (Mexico City): "large tomatoes, small tomatoes, leaf tomatoes, sweet tomatoes, large serpent tomatoes, nipple-shaped tomatoes", and tomatoes of all colors from the brightest red to the deepest yellow.[13] Bernardino de Sahagún mentioned Aztecs cooking various sauces, some with and without tomatoes of different sizes, serving them in city markets: "foods sauces, hot sauces; fried [food], olla-cooked [food], juices, sauces of juices, shredded [food] with chile, with squash seeds [most likely Cucurbita pepo], with tomatoes, with smoked chile, with hot chile, with yellow chile, with mild red chile sauce, yellow chile sauce, hot chile sauce, with "bird excrement" sauce, sauce of smoked chile, heated [sauces], bean sauce; [he sells] toasted beans, cooked beans, mushroom sauce, sauce of small squash, sauce of large tomatoes, sauce of ordinary tomatoes, sauce of various kinds of sour herbs, avocado sauce."[14]

Spanish distribution

Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés may have been the first to transfer a small yellow tomato to Europe after he captured the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City, in 1521. The earliest discussion of the tomato in European literature appeared in a herbal written in 1544 by Pietro Andrea Mattioli, an Italian physician and botanist, who suggested that a new type of eggplant had been brought to Italy that was blood red or golden color when mature and could be divided into segments and eaten like an eggplant—that is, cooked and seasoned with salt, black pepper, and oil. It was not until ten years later that tomatoes were named in print by Mattioli as pomi d'oro, or "golden apples".[10]: 13

After the Spanish colonization of the Americas, the Spanish distributed the tomato throughout their colonies in the Caribbean. They also took it to the Philippines, from where it spread to southeast Asia and then the entire Asian continent. The Spanish also brought the tomato to Europe. It grew easily in Mediterranean climates, and cultivation began in the 1540s. It was probably eaten shortly after it was introduced, and was certainly being used as food by the early 17th century in Spain.

China

The tomato was introduced to China, likely via the Philippines or Macau, in the 1500s. It was given the name 番茄 fānqié (foreign eggplant), as the Chinese named many foodstuffs introduced from abroad, but referring specifically to early introductions.[15]

Italy

The recorded history of tomatoes in Italy dates back to at least 31 October 1548, when the house steward of Cosimo de' Medici, the grand duke of Tuscany, wrote to the Medici private secretary informing him that the basket of tomatoes sent from the grand duke's Florentine estate at Torre del Gallo "had arrived safely".[16] Tomatoes were grown mainly as ornamentals early on after their arrival in Italy. For example, the Florentine aristocrat Giovanvettorio Soderini wrote how they "were to be sought only for their beauty", and were grown only in gardens or flower beds. The tomato's ability to mutate and create new and different varieties helped contribute to its success and spread throughout Italy. However, in areas where the climate supported growing tomatoes, their habit of growing to the ground suggested low status. They were not adopted as a staple of the peasant population because they were not as filling as other fruits already available. Additionally, both toxic and inedible varieties discouraged many people from attempting to consume or prepare any other varieties.[17] In certain areas of Italy, such as Florence, the fruit was used solely as a tabletop decoration, until it was incorporated into the local cuisine in the late 17th or early 18th century.[18] The earliest discovered cookbook with tomato recipes was published in Naples in 1692, though the author had apparently obtained these recipes from Spanish sources.[10]: 17

Unique varieties were developed over the next several hundred years for uses such as dried tomatoes, sauce tomatoes, pizza tomatoes, and tomatoes for long-term storage. These varieties are usually known for their place of origin as much as by a variety name. For example, Pomodorino del Piennolo del Vesuvio is the "hanging tomato of Vesuvius", or the well known and highly prized San Marzano plum tomato grown in that region.

Britain

Tomatoes were not grown in England until the 1590s. One of the earliest cultivators was John Gerard, a barber-surgeon. Gerard's Herbal, published in 1597, and largely plagiarized from continental sources, is also one of the earliest discussions of the tomato in England. Gerard knew the tomato was eaten in Spain and Italy. Nonetheless, he believed it was poisonous (in fact, the plant and raw fruit do have low levels of tomatine, but are not generally dangerous; see below). Gerard's views were influential, and the tomato was considered unfit for eating (though not necessarily poisonous) for many years in Britain and its North American colonies.[10]: 17

However, by the mid-18th century, tomatoes were widely eaten in Britain, and before the end of that century, the Encyclopædia Britannica stated the tomato was "in daily use" in soups, broths, and as a garnish. They were not part of the average person's diet, and though by 1820 they were described as "to be seen in great abundance in all our vegetable markets" and to be "used by all our best cooks", reference was made to their cultivation in gardens still "for the singularity of their appearance", while their use in cooking was associated with exotic Italian or Jewish cuisine.[19] For example, in Elizabeth Blackwell's A Curious Herbal, it is described under the name "Love Apple (Amoris Pomum)" as being consumed with oil and vinegar in Italy, similar to consumption of cucumbers in the UK.[20]

Middle East and North Africa

The tomato was introduced to cultivation in the Middle East by John Barker, British consul in Aleppo c. 1799 to 1825.[21][22] Nineteenth century descriptions of its consumption are uniformly as an ingredient in a cooked dish. In 1881, it is described as only eaten in the region "within the last forty years".[23] Today, the tomato is a critical and ubiquitous part of Middle Eastern cuisine, served fresh in salads (e.g., Arab salad, Israeli salad, Shirazi salad and Turkish salad), grilled with kebabs and other dishes, made into sauces, and so on.

United States

The earliest reference to tomatoes being grown in British North America is from 1710, when herbalist William Salmon reported seeing them in what is today South Carolina.[10]: 25 They may have been introduced from the Caribbean. By the mid-18th century, they were cultivated on some Carolina plantations, and probably in other parts of the Southeast as well. Thomas Jefferson, who ate tomatoes in Paris, sent some seeds back to America.[10]: 28 Some early American advocates of the culinary use of the tomato included Michele Felice Cornè and Robert Gibbon Johnson.[24] Many Americans considered tomatoes to be poisonous at this time; and in general, they were grown more as ornamental plants than as food. In 1897, W. H. Garrison addressed the Medico-Legal Society of New York stating, "The belief was once transmitted that the tomato was sinisterly dangerous." He recalled in his youth tomatoes were dubbed "love-apples or wolf-apples" and they were shunned as "globes of the devil."[25]

Alexander W. Livingston receives much credit for developing numerous varieties of tomato for both home and commercial gardeners.[26]

Early tomato breeders included Henry Tilden in Iowa and a Dr. Hand in Baltimore.[27] The U.S. Department of Agriculture's 1937 yearbook declared that "half of the major varieties were a result of the abilities of the Livingstons to evaluate and perpetuate superior material in the tomato." Livingston's first breed of tomato, the Paragon, was introduced in 1870, the beginning of a great tomato culture enterprise in the county. In 1875, he introduced the Acme, which was said to be involved in the parentage of most of the tomatoes introduced by him and his competitors for the next twenty-five years.[28][29]

When Livingston began his attempts to develop the tomato as a commercial crop, his aim had been to grow tomatoes smooth in contour, uniform in size, and sweet in flavor. He eventually developed over seventeen different varieties of the tomato plant.[28] Today, the crop is grown in every state in the Union.[30]

Because of the long growing season needed for this heat-loving crop, several states in the US Sun Belt became major tomato-producers, particularly Florida and California. In California, tomatoes are grown under irrigation for both the fresh fruit market and for canning and processing. The University of California, Davis (UC Davis) became a major center for research on the tomato. The C.M. Rick Tomato Genetics Resource Center at UC Davis is a gene bank of wild relatives, monogenic mutants and miscellaneous genetic stocks of tomato.[31] The center is named for the late Dr. Charles M. Rick, a pioneer in tomato genetics research.[32] Research on processing tomatoes is also conducted by the California Tomato Research Institute in Escalon, California.[33]

In California, growers have used a method of cultivation called dry-farming, especially with Early Girl tomatoes. This technique encourages the plant to send roots deep to find existing moisture in soil that retains moisture, such as clayey soil.

Modern commercial varieties

The poor taste and lack of sugar in modern garden and commercial tomato varieties resulted from breeding tomatoes to ripen uniformly red. This change occurred after discovery of a mutant "u" phenotype in the mid-20th century, so named because the fruits ripened uniformly. This was widely cross-bred to produce red fruit without the typical green ring around the stem on uncross-bred varieties. Prior to general introduction of this trait, most tomatoes produced more sugar during ripening, and were sweeter and more flavorful.[34][35]

Evidence has been found that 10–20% of the total carbon fixed in the fruit can be produced by photosynthesis in the developing fruit of the normal U phenotype. The u genetic mutation encodes a factor that produces defective chloroplasts with lower density in developing fruit, resulting in a lighter green colour of unripe fruit, and repression of sugars accumulation in the resulting ripe fruit by 10–15%. Perhaps more important than their role in photosynthesis, the fruit chloroplasts are remodelled during ripening into chlorophyll-free chromoplasts that synthesize and accumulate the carotenoids lycopene, β-carotene, and other metabolites that are sensory and nutritional assets of the ripe fruit. The potent chloroplasts in the dark-green shoulders of the U phenotype are beneficial here, but have the disadvantage of leaving green shoulders near the stems of the ripe fruit, and even cracked yellow shoulders, apparently because of oxidative stress due to overload of the photosynthetic chain in direct sunlight at high temperatures. Hence genetic design of a commercial variety that combines the advantages of types u and U requires fine tuning, but may be feasible.[36]

Furthermore, breeders of modern tomato cultivars typically strive to produce tomato plants exhibiting improved yield, shelf life, size, and tolerance/resistance to various environmental pressures, including disease.[37][38] However, these breeding efforts have yielded unintended negative consequences on various tomato fruit attributes. For instance, linkage drag is a phenomenon that has been responsible for alterations in the metabolism of the tomato fruit. Linkage drag describes the introduction of an undesired trait or allele into a plant during backcrossing. This trait/allele is physically linked (or is very close) to the desired allele along the chromosome. In introducing the beneficial allele, there exists a high likelihood that the poor allele is also incorporated into the plant. Thus, breeding efforts attempting to enhance certain traits (for example: larger fruit size) have unintentionally altered production of chemicals associated with, for instance, nutritional value and flavor.[37]

Breeders have turned to using wild tomato species as a source of alleles for the introduction of beneficial traits into modern tomato varieties. For example, wild tomato relatives may possess higher amounts of fruit solids (which are associated with greater sugar content) or resistance to diseases caused by microbes, such as resistance towards the early blight pathogen Alternaria solani. However, this tactic has limitations, for the incorporation of certain traits, such as pathogen resistance, can negatively impact other favorable phenotypes, such as fruit production.[38][39]

Etymology

The word tomato comes from the Spanish tomate, which in turn comes from the Nahuatl word tomatl [ˈtomat͡ɬ] ⓘ, meaning 'swelling fruit';[4] also 'fat water' or 'fat thing'.[40] The native Mexican tomatillo is tomate. When Aztecs started to cultivate the fruit to be larger, sweeter and red, they called the new variety xitomatl (or jitomates) (pronounced [ʃiːˈtomatɬ]),[2] ('plump with navel' or 'fat water with navel'). The specific name lycopersicum (from the 1753 book Species Plantarum) is of Greek origin (λύκοπερσικων, lykopersikon), meaning 'wolf peach'.

Pronunciation

The usual pronunciations of tomato are /təˈmeɪtoʊ/ tə-MAY-toh (usual in North American English) and /təˈmɑːtoʊ/ tə-MAH-toh (usual in British English).[41] The word's dual pronunciations were immortalized in Ira and George Gershwin's 1937 song "Let's Call the Whole Thing Off" ("You like /pəˈteɪtoʊ/ and I like /pəˈtɑːtoʊ/ / You like /təˈmeɪtoʊ/ and I like /təˈmɑːtoʊ/") and have become a symbol for nitpicking pronunciation disputes. In this capacity, it has even become an American and British slang term: saying "/təˈmeɪtoʊ təˈmɑːtoʊ/" when presented with two choices can mean "What's the difference?" or "It's all the same to me".

Botany

Description

Tomato plants are vines, initially decumbent, typically growing 180 cm (6 ft) or more above the ground if supported, although erect bush varieties have been bred, generally 100 cm (3 ft 3 in) tall or shorter. Indeterminate types are "tender" perennials, dying annually in temperate climates (they are originally native to tropical highlands), although they can live up to three years in a greenhouse in some cases. Determinate types are annual in all climates.

Tomato plants are dicots, and grow as a series of branching stems, with a terminal bud at the tip that does the actual growing. When the tip eventually stops growing, whether because of pruning or flowering, lateral buds take over and grow into other, fully functional, vines.[42]

Tomato vines are typically pubescent, meaning covered with fine short hairs. The hairs facilitate the vining process, turning into roots wherever the plant is in contact with the ground and moisture, especially if the vine's connection to its original root has been damaged or severed.

Most tomato plants have compound leaves, and are called regular leaf (RL) plants, but some cultivars have simple leaves known as potato leaf (PL) style because of their resemblance to that particular relative. Of RL plants, there are variations, such as rugose leaves, which are deeply grooved, and variegated, angora leaves, which have additional colors where a genetic mutation causes chlorophyll to be excluded from some portions of the leaves.[43]

The leaves are 10–25 cm (4–10 in) long, odd pinnate, with five to nine leaflets on petioles,[44] each leaflet up to 8 cm (3 in) long, with a serrated margin; both the stem and leaves are densely glandular-hairy.

Their flowers, appearing on the apical meristem, have the anthers fused along the edges, forming a column surrounding the pistil's style. Flowers in domestic cultivars can be self-fertilizing. The flowers are 1–2 cm (1⁄2–3⁄4 in) across, yellow, with five pointed lobes on the corolla; they are borne in a cyme of three to 12 together.

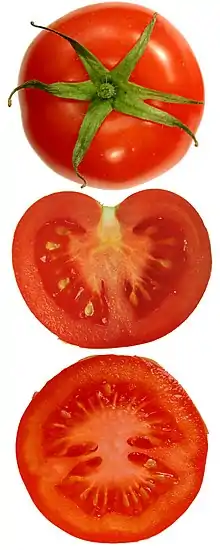

Although in culinary terms, tomato is regarded as a vegetable, its fruit is classified botanically as a berry.[45] As a true fruit, it develops from the ovary of the plant after fertilization, its flesh comprising the pericarp walls. The fruit contains hollow spaces full of seeds and moisture, called locular cavities. These vary, among cultivated species, according to type. Some smaller varieties have two cavities, globe-shaped varieties typically have three to five, beefsteak tomatoes have a great number of smaller cavities, while paste tomatoes have very few, very small cavities.[46][47][48]

For propagation, the seeds need to come from a mature fruit, and must be lightly fermented to remove the gelatinous outer coating and then dried before use.[49]

Classification

In 1753, Linnaeus placed the tomato in the genus Solanum (alongside the potato) as Solanum lycopersicum. In 1768, Philip Miller moved it to its own genus, naming it Lycopersicon esculentum.[50] The name came into wide use, but was technically in breach of the plant naming rules because Linnaeus's species name lycopersicum still had priority. Although the name Lycopersicum lycopersicum was suggested by Karsten (1888), it is not used because it violates the International Code of Nomenclature[51] barring the use of tautonyms in botanical nomenclature. The corrected name Lycopersicon lycopersicum (Nicolson 1974) was technically valid, because Miller's genus name and Linnaeus's species name differ in exact spelling, but since Lycopersicon esculentum has become so well known, it was officially listed as a nomen conservandum in 1983, and would be the correct name for the tomato in classifications which do not place the tomato in the genus Solanum.

Genetic evidence has now shown that Linnaeus was correct to put the tomato in the genus Solanum, making Solanum lycopersicum the correct name.[1][52] Both names, however, will probably be found in the literature for some time. Two of the major reasons for considering the genera separate are the leaf structure (tomato leaves are markedly different from any other Solanum), and the biochemistry (many of the alkaloids common to other Solanum species are conspicuously absent from the tomato). On the other hand, hybrids of tomato and diploid potato can be created in the lab by somatic fusion, and are partially fertile,[53] providing evidence of the close relationship between these species.

Genetics and genetic modification

Genome

An international consortium of researchers from 10 countries, began sequencing the tomato genome in 2004.[54][55] A prerelease version of the genome was made available in December 2009.[56] The complete genome for the cultivar Heinz 1706 was published on 31 May 2012 in Nature.[57] The latest reference genome published in 2021 had 799 MB and encodes 34,384 (predicted) proteins, spread over 12 chromosomes.[58]

Genetic modification

Since many other fruits, like strawberries, apples, melons, and bananas share the same characteristics and genes, researchers stated the published genome could help to improve food quality, food security and reduce costs of all of these fruits.[59]

The first commercially available genetically modified food was a tomato called Flavr Savr, which was engineered to have a longer shelf life.[60] However, it is no longer commercially available. Scientists are continuing to develop tomatoes with new traits not found in natural crops, such as increased resistance to pests or environmental stresses or better flavor.

Breeding

The Tomato Genetic Resource Center, Germplasm Resources Information Network, AVRDC, and numerous seed banks around the world store seed representing genetic variations of value to modern agriculture. These seed stocks are available for legitimate breeding and research efforts. While individual breeding efforts can produce useful results, the bulk of tomato breeding work is at universities and major agriculture-related corporations. These efforts have resulted in significant regionally adapted breeding lines and hybrids, such as the Mountain series from North Carolina. Corporations including Heinz, Monsanto, BHNSeed, and Bejoseed have breeding programs that attempt to improve production, size, shape, color, flavor, disease tolerance, pest tolerance, nutritional value, and numerous other traits.

Fruit versus vegetable

Botanically, a tomato is a fruit—a berry, consisting of the ovary, together with its seeds, of a flowering plant.[61] However, the tomato is considered a "culinary vegetable" because it has a much lower sugar content than culinary fruits; because it is more savoury (umami) than sweet, it is typically served as part of a salad or main course of a meal, rather than as a dessert.[62] Tomatoes are not the only food source with this ambiguity; bell peppers, cucumbers, green beans, aubergines/eggplants, avocados, and squashes of all kinds (such as courgettes/zucchini and pumpkins) are all botanically fruit, yet cooked as vegetables.[63]

The confusion on whether tomatoes are fruits or vegetables has led to legal dispute in the United States. In 1887, U.S. tariff laws that imposed a duty on vegetables, but not on fruit, caused the tomato's status to become a matter of legal importance. In Nix v. Hedden, the U.S. Supreme Court settled the tariff controversy on 10 May 1893, by declaring that the tomato is a vegetable, based on the popular definition that classifies vegetables by use—they are generally served with dinner and not dessert.[64] The holding of this case applies only to the interpretation of the Tariff of 1883, and the court did not purport to reclassify the tomato for botanical or other purposes.

Cultivation

The tomato is grown worldwide for its edible fruits, with thousands of cultivars.[65] A fertilizer with an NPK ratio of 5–10–10 is often sold as tomato fertilizer or vegetable fertilizer, although manure and compost are also used. On average there are 150,000 seeds in a pound of tomato seeds.[66]

Diseases

Tomato cultivars vary widely in their resistance to disease. Modern hybrids focus on improving disease resistance over the heirloom plants.

Various forms of mildew and blight are common tomato afflictions, which is why tomato cultivars are often marked with a combination of letters that refer to specific disease resistance. The most common letters are:

- LB – 'late blight'[67]

- V – verticillium wilt

- F – fusarium wilt strain I

- FF – fusarium wilt strain I and II

- N – nematodes

- T – tobacco mosaic virus, and

- A – alternaria.

A common tomato disease is tobacco mosaic virus. Handling cigarettes and other infected tobacco products can transmit the virus to tomato plants.[68]

Another particularly dreaded disease is curly top, carried by the beet leafhopper, which interrupts the lifecycle. As the name implies, it has the symptom of making the top leaves of the plant wrinkle up and grow abnormally.

Bacterial wilt is another common disease impacting yield.[69] Wang et al., 2019 found phage combination therapies to reduce the impact of bacterial wilt, sometimes by reducing bacterial abundance and sometimes by selecting for resistant but slow growing genetics.[69]

Pests

Some common tomato pests are the tomato bug, stink bugs, cutworms, tomato hornworms and tobacco hornworms, aphids, cabbage loopers, whiteflies, tomato fruitworms, flea beetles, red spider mite, slugs,[70] and Colorado potato beetles. The tomato russet mite, Aculops lycopersici, feeds on foliage and young fruit of tomato plants, causing shrivelling and necrosis of leaves, flowers, and fruit, possibly killing the plant.[71]

After an insect attack tomato plants produce systemin, a plant peptide hormone. Systemin activates defensive mechanisms, such as the production of protease inhibitors to slow the growth of insects. The hormone was first identified in tomatoes, but similar proteins have been identified in other species since.[72]

Other disorders

Although not a disease as such, irregular supplies of water can cause growing or ripening fruit to split. Besides cosmetic damage, the splits may allow decay to start, although growing fruits have some ability to heal after a split. In addition, a deformity called cat-facing can be caused by pests, temperature stress, or poor soil conditions. Affected fruit usually remains edible, but its appearance may be unsightly.

Companion plants

Tomatoes serve, or are served by, a large variety of companion plants.

The devastating tomato hornworm has a major predator in various parasitic wasps, whose larvae devour the hornworm, but whose adult form drinks nectar from tiny-flowered plants like umbellifers. Several species of umbellifer are therefore often grown with tomato plants, including parsley, Queen Anne's lace, and occasionally dill. These also attract predatory flies that attack various tomato pests.[73]

Borage is thought to repel the tomato hornworm moth.[74]

Basil is popularly recommended as a companion plant to the tomato. Common claims are that basil may deter pests or improve tomato flavor. However, in double-blind taste tests, basil did not significantly affect the taste of tomatoes when planted adjacent to them.[75][76]

Tomato plants can protect asparagus from asparagus beetles, because they contain solanine that kills this pest, while asparagus plants contain asparagusic acid that repels nematodes known to attack tomato plants.[77] Marigolds also repel nematodes.[78][79][80]

Pollination

In the wild, original state, tomatoes required cross-pollination; they were much more self-incompatible than domestic cultivars. As a floral device to reduce selfing, the pistil of wild tomatoes extends farther out of the flower than today's cultivars. The stamens were, and remain, entirely within the closed corolla.

As tomatoes were moved from their native areas, their traditional pollinators (probably a species of halictid bee) did not move with them.[81] The trait of self-fertility became an advantage, and domestic cultivars of tomato have been selected to maximize this trait.[81]

This is not the same as self-pollination, despite the common claim that tomatoes do so. That tomatoes pollinate themselves poorly without outside aid is clearly shown in greenhouse situations, where pollination must be aided by artificial wind, vibration of the plants (one brand of vibrator is a wand called an "electric bee" that is used manually), or more often today, by cultured bumblebees.[82] The anther of a tomato flower is shaped like a hollow tube, with the pollen produced within the structure, rather than on the surface, as in most species. The pollen moves through pores in the anther, but very little pollen is shed without some kind of externally-induced motion. The ideal vibratory frequencies to release pollen grains are provided by an insect, such as a bumblebee, or the original wild halictid pollinator, capable of engaging in a behavior known as buzz pollination, which honey bees cannot perform. In an outdoors setting, wind or animals usually provide sufficient motion to produce commercially viable crops.

Fruit formation

Pollination and fruit formation depend on meiosis. Meiosis is central to the processes by which diploid microspore mother cells within the anther give rise to haploid pollen grains, and megaspore mother cells in ovules that are contained within the ovary give rise to haploid nuclei. Union of haploid nuclei from pollen and ovule (fertilization) can occur either by self- or cross-pollination. Fertilization leads to the formation of a diploid zygote that can then develop into an embryo within the emerging seed. Repeated fertilizations within the ovary are accompanied by maturation of the ovary to form the tomato fruit.

Homologs of the recA gene, including rad51, play a key role in homologous recombinational repair of DNA during meiosis. A rad51 homolog is present in the anther of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum),[83] suggesting that recombinational repair occurs during meiosis in tomato.

Hydroponic and greenhouse cultivation

Tomatoes are often grown in greenhouses in cooler climates, and cultivars such as the British 'Moneymaker' and a number of cultivars grown in Siberia are specifically bred for indoor growing. In more temperate climates, it is not uncommon to start seeds in greenhouses during the late winter for future transplant.

Greenhouse tomato production in large-acreage commercial greenhouses and owner-operator stand-alone or multiple-bay greenhouses is on the increase, providing fruit during those times of the year when field-grown fruit is not readily available. Smaller sized fruit (cherry and grape), or cluster tomatoes (fruit-on-the-vine) are the fruit of choice for the large commercial greenhouse operators while the beefsteak varieties are the choice of owner-operator growers.[84]

Hydroponic technique is often used in hostile growing environments, as well as high-density plantings.

Picking and ripening

To facilitate transportation and storage, tomatoes are often picked unripe (green) and ripened in storage with ethylene.[85]

A machine-harvestable variety of tomato (the "square tomato") was developed in the 1950s by University of California, Davis's Gordie C. Hanna, which, in combination with the development of a suitable harvester, revolutionized the tomato-growing industry. This type of tomato is grown commercially near plants that process and can tomatoes, tomato sauce, and tomato paste. They are harvested when ripe and are flavorful when picked. They are harvested 24 hours a day, seven days a week during a 12- to 14-week season, and immediately transported to packing plants, which operate on the same schedule. California is a center of this sort of commercial tomato production and produces about a third of the processed tomatoes produced in the world.[86]

In 1994, Calgene introduced a genetically modified tomato called the FlavrSavr, which could be vine ripened without compromising shelf life. However, the product was not commercially successful, and was sold only until 1997.[87]

Yield

The world dedicated 4.8 million hectares in 2012 for tomato cultivation and the total production was about 161.8 million tonnes.[88] The average world farm yield for tomato was 33.6 tonnes per hectare in 2012.[88]

Tomato farms in the Netherlands were the most productive in 2012, with a nationwide average of 476 tonnes per hectare, followed by Belgium (463 tonnes per hectare) and Iceland (429 tonnes per hectare).[89]

Records

As of 2008, the heaviest tomato harvested weighed 3.51 kg (7 lb 12 oz), was of the cultivar "Delicious", and was grown by Gordon Graham of Edmond, Oklahoma in 1986.[90] The largest tomato plant grown was of the cultivar "Sungold" and reached 19.8 m (65 ft) in length, grown by Nutriculture Ltd (UK) of Mawdesley, Lancashire, UK, in 2000.[91]

A massive "tomato tree" growing inside the Walt Disney World Resort's experimental greenhouses in Lake Buena Vista, Florida may have been the largest single tomato plant in the world. The plant has been recognized as a Guinness World Record Holder, with a harvest of more than 32,000 tomatoes and a total weight of 522 kg (1,151 lb).[92] It yielded thousands of tomatoes at one time from a single vine. Yong Huang, Epcot's manager of agricultural science, discovered the unique plant in Beijing, China. Huang brought its seeds to Epcot and created the specialized greenhouse for the fruit to grow. The vine grew golf ball-sized tomatoes, which were served at Walt Disney World restaurants.[93] The tree developed a disease and was removed in April 2010 after about 13 months of life.

Tomato plants 7 days after planting

Tomato plants 7 days after planting Tomato seedlings growing indoors

Tomato seedlings growing indoors 27 days after planting

27 days after planting 52-day-old plant, first fruits

52-day-old plant, first fruits Tomatoes being collected from the field, Maharashtra, India

Tomatoes being collected from the field, Maharashtra, India

Production

| Tomato production – 2021 | |

|---|---|

| Producer | (Millions of tonnes) |

67.5 | |

21.2 | |

17.9 | |

13.1 | |

10.5 | |

6.3 | |

4.1 | |

3.7 | |

3.6 | |

3.4 | |

| World | 189.1 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[94] | |

In 2021, world production of tomatoes was 189 million tonnes, with China accounting for 35% of the total, followed by India, the European Union, Turkey, and the United States as major producers (see table).

Toxicity

The leaves, stem, and green unripe fruit of the tomato plant contain small amounts of the alkaloid tomatine, whose effect on humans has not been studied.[9] They also contain small amounts of solanine, a toxic alkaloid found in potato leaves and other plants in the nightshade family.[95][96] However, solanine concentrations in foliage and green fruit are generally too small to be dangerous unless large amounts are consumed—for example, as greens.

Small amounts of tomato foliage are sometimes used for flavoring without ill effect, and the green fruit of unripe red tomato varieties is sometimes used for cooking, particularly as fried green tomatoes.[9] There are also tomato varieties with fully ripe fruit that is still green. Compared to potatoes, the amount of solanine in unripe green or fully ripe tomatoes is low. However, even in the case of potatoes, while solanine poisoning resulting from dosages several times the normal human consumption has been demonstrated, actual cases of poisoning from excessive consumption of potatoes are rare.[96]

Tomato plants can be toxic to dogs if they eat large amounts of the fruit, or chew plant material.[97]

Salmonella

Tomatoes were linked to seven Salmonella outbreaks between 1990 and 2005,[98] and may have been the cause of a salmonellosis outbreak causing 172 illnesses in 18 US states in 2006.[99] The 2008 United States salmonellosis outbreak caused the temporary removal of tomatoes from stores and restaurants across the United States and parts of Canada,[100] although other foods, including jalapeño and serrano peppers, may have been involved.

Uses

Culinary

Though it is botanically a berry, a subset of fruit, the tomato is considered a vegetable for culinary purposes. It has a strong savoury umami flavour, rather than significant sweetness (see above). Chef Heston Blumenthal observed that the inner pulp had more flavour that the flesh; a subsequent academic study in which he participated confirmed that the pulp had up to eleven times more glutamic acid, which carries umami flavour, than the flesh.[101]

Although tomatoes originated in the Americas, the tomato is now grown and eaten around the world. It is used in diverse ways, including raw in salads or in slices, stewed, incorporated into a wide variety of dishes, or processed into ketchup or tomato soup. Unripe green tomatoes can also be breaded and fried, used to make salsa, or pickled. Tomato juice is sold as a drink, and is used in cocktails such as the Bloody Mary.

Tomatoes have become extensively used in Mediterranean cuisine as a key ingredient in pizza and many pasta sauces.[6] Tomatoes are also used in Spanish and Catalan dishes, such as gazpacho and pa amb tomàquet.

Storage

Tomatoes keep best unwashed at room temperature and out of direct sunlight. It is not recommended to refrigerate them as they take a mealy texture and lose flavour.[102][103]

Storing stem down can prolong shelf life,[104] as it may keep from rotting too quickly.[105]

Unripe tomatoes can be kept in a paper bag to ripen.[106]

Tomatoes are easy to preserve whole, chopped, or as tomato sauce or concentrated paste by home canning. The fruit can also be preserved by drying, sometimes in the sun where climate permits, and sold either in bags or in jars with oil.

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 74 kJ (18 kcal) |

3.9 g | |

| Sugars | 2.6 g |

| Dietary fiber | 1.2 g |

0.2 g | |

0.9 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 5% 42 μg4% 449 μg123 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 3% 0.037 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 2% 0.019 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 4% 0.594 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 2% 0.089 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 6% 0.08 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 4% 15 μg |

| Vitamin C | 17% 14 mg |

| Vitamin E | 4% 0.54 mg |

| Vitamin K | 8% 7.9 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 1% 10 mg |

| Iron | 2% 0.27 mg |

| Magnesium | 3% 11 mg |

| Manganese | 5% 0.114 mg |

| Phosphorus | 3% 24 mg |

| Potassium | 5% 237 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 5 mg |

| Zinc | 2% 0.17 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 94.5 g |

| Lycopene | 2573 μg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

A raw tomato is 95% water, contains 4% carbohydrates, and has less than 1% each of fat and protein (see table). 100 grams (3.5 oz) of raw tomatoes supply 18 kilocalories and are a moderate source of vitamin C (17% of the Daily Value), but otherwise have low micronutrient content (table).

Research

An extensive review in 2022 found and specified many health benefits associated with eating tomatoes, and some risks, due both to external factors (pesticides, microbial contamination, heavy metals from contaminated soil), and intrinsic; for example, lycopene, at least as a supplement, has anti-platelet effect undesirable for patients on blood thinners and similar medications. The review concludes that "the synergistic effects of all tomato constituents are likely to outweigh the benefits of tomato's individual constituents, such as lycopene".[107]

Studies in 2014 and 2015 did not find conclusive evidence to indicate that the lycopene in tomatoes or in supplements affects the onset of cardiovascular diseases or cancer.[108][109]

In the United States, supposed health benefits of consuming tomatoes, tomato products or lycopene to affect cancer cannot be mentioned on packaged food products without a qualified health claim statement.[110] In a scientific review of potential claims for lycopene favorably affecting DNA, skin exposed to ultraviolet radiation, heart function and vision, the European Food Safety Authority concluded in 2011 that the evidence for lycopene having any of these effects was inconclusive.[111]

Host plant

The potato tuber moth (Phthorimaea operculella) is an oligophagous insect that prefers to feed on plants of the family Solanaceae such as tomato plants. Female P. operculella use the leaves to lay their eggs and the hatched larvae will eat away at the mesophyll of the leaf.[112]

Tomato forms a mutually beneficial symbiosis with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi such as Rhizophagus irregularis. Scientists use tomato as a model species for investigating this symbiosis.[113]

In popular culture

The town of Buñol, Spain, annually celebrates La Tomatina, a festival centered on an enormous tomato fight. On 30 August 2007, 40,000 Spaniards gathered to throw 115,000 kg (254,000 lb) of tomatoes at each other in the festival.[114]

Several US states have adopted the tomato as a state fruit or vegetable (see above). Tomatoes have been designated the state vegetable of New Jersey. Arkansas took both sides by declaring the South Arkansas Vine Ripe Pink Tomato both the state fruit and the state vegetable in the same law, citing both its culinary and botanical classifications. In 2009, the state of Ohio passed a law making the tomato the state's official fruit. Tomato juice has been the official beverage of Ohio since 1965. Alexander W. Livingston, of Reynoldsburg, Ohio, played a large part in popularizing the tomato in the late 19th century; his efforts are commemorated in Reynoldsburg with an annual Tomato Festival.

Flavr Savr was the first commercially grown genetically engineered food licensed for human consumption.[115]

Tomatoes are a popular "nonlethal" throwing weapon in mass protests, and there was a common tradition of throwing rotten tomatoes at bad performers on a stage during the 19th century; today this is usually referenced as a metaphor. Embracing it for this protest connotation, the Dutch Socialist party adopted the tomato as their logo.

The US city of Reynoldsburg, Ohio calls itself "The Birthplace of the Tomato", claiming the first commercial variety of tomato was bred there in the 19th century.[28]

"Rotten Tomatoes" is an American review-aggregation website for film and television. The name "Rotten Tomatoes" derives from the practice of audiences throwing rotten tomatoes when disapproving of a poor stage performance.

Gallery

Various heirloom tomato (heritage tomato in British English) cultivars

Various heirloom tomato (heritage tomato in British English) cultivars Homegrown multicolored tomatoes

Homegrown multicolored tomatoes A variety of cultivars, including Brandywine (biggest red), Black Krim (lower left) and Green Zebra (top left)

A variety of cultivars, including Brandywine (biggest red), Black Krim (lower left) and Green Zebra (top left) Red tomatoes with PLU code in a supermarket

Red tomatoes with PLU code in a supermarket

See also

- List of countries by tomato production

- List of tomato dishes

- Marglobe, an early attempt at breeding a disease-resistant tomato

- Ring culture

- Physalis, a similar fruit also used in cooking

- Tomato effect

- Tomato jam

- Nightshades

References

- 1 2 3 "Phylogeny".

Molecular phylogenetic analyses have established that the formerly segregate genera Lycopersicon, Cyphomandra, Normania, and Triguera are nested within Solanum, and all species of these four genera have been transferred to Solanum

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Garden Tomato. Solanum lycopersicum L." Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Tomato". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 4 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- 1 2 "Tomato". Etymology Online Dictionary. 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ↑ "Tomato History". Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- 1 2 Fleming, Amy (9 April 2013). "Umami: why the fifth taste is so important". The Guardian, London, UK. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- 1 2 Estabrook, Barry (22 July 2015). "Why Is This Wild, Pea-Sized Tomato So Important?". Smithsonian Journeys Quarterly. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ Smith, K. Annabelle. "Why the Tomato Was Feared in Europe for More Than 200 Years". Smithsonian Magazine.

- 1 2 3 Mcgee, H. (29 July 2009). "Accused, Yes, but Probably Not a Killer". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Smith, A. F. (1994). The Tomato in America: Early History, Culture, and Cookery. Columbia SC, US: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-000-0.

- ↑ Donnelly, L. (26 October 2008). "Killer Tomatoes". The East Hampton Star. Archived from the original on 29 May 2009.

- ↑ The Aztecs, Richard F. Townsend [Thames and Hudson:London], revised edition 2000 (p. 180-1)

- ↑ SILVERTOWN, J. (2017). Vegetables—Variety. DINNER WITH DARWIN: Food, drink, and evolution. S.l.: UNIV OF CHICAGO PRESS.(p. 145)

- ↑ Sophie D. Coe (2015). America's First Cuisines (page 117). University of Texas Press: Austin TX. pp. 108–118. ISBN 978-1477309711.

- ↑ Kiple, Kenneth F.; Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè (2000). The Cambridge World History of Food. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-521-40214-9.

- ↑ "Tomato Museum: 05 – The History of Tomato". I Musei del Cibo della provincia di Parma.

- ↑ Gentilcore, David (2010) Pomodoro! A History of the Tomato in Italy New York, NY: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-15206-X.

- ↑ Staller, John; Carrasco, Michael (2009). Pre-Columbian Foodways: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Food, Culture, and Markets in Ancient Mesoamerica. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 44. ISBN 9781441904713. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ↑ 'LOVE-APPLE, or TOMATO BERRY.-Love apples are now to be seen in great abundance at all our vegetable markets.' The Times (London, England), 22 September 1820, p.3

- ↑ Elizabeth Blackwell (1737). A curious herbal: containing five hundred cuts, of the most useful plants, which are now used in the practice of physick : engraved on folio copper plates, after drawings taken from life (PDF). p. 342 (plate 133).

- ↑ "British Consuls in Aleppo – Your Archives". Yourarchives.nationalarchives.gov.uk. 26 January 2009. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ↑ "Syria under the last five Turkish Sultans". Appletons' Journal. Vol. 1. D. Appleton and Co. 1876. p. 519.

- ↑ "Natural History, Science, &c". The Friend. 54: 223. 1881.

- ↑ McCue, George Allen (November 1952). "The History of the Use of the Tomato: An Annotated Bibliography". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. Missouri Botanical Garden Press. 39 (4): 336–338. doi:10.2307/2399094. JSTOR 2399094.

- ↑ Quoted in Chris Harrald, and Fletcher Watkins, The cigarette book: the history and culture of smoking (Skyhorse Publishing, 2010) p. 185.

- ↑ Smith, A. F. (1994). The Tomato in America: Early History, Culture, and Cookery. Columbia SC, US: University of South Carolina Press, p. 152.

- ↑ Boswell, Victor R. "Improvement and Genetics of Tomatoes, Peppers, and Eggplant," Yearbook of Agriculture, 1937, p. 179. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Accessed 25 May 2018/

- 1 2 3 About Reynoldsburg. ci.reynoldsburg.oh.us

- ↑ Boswell, Victor R. "Improvement and Genetics of Tomatoes, Peppers, and Eggplant," Yearbook of Agriculture, 1937, pp. 178–81. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Accessed 25 May 2018/

- ↑ "Tomatoes." AgMRC, March 2017. Accessed 25 May 2018.

- ↑ "C. M. Rick Tomato Genetics Resource Center". UC Davis. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ↑ "UC Newsroom, UC Davis Tomato Geneticist Charles Rick Dies at 87". University of California. 8 May 2002. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ↑ California Tomato Research Institute. tomatonet.org

- ↑ Powell AL, Nguyen CV, Hill T, Cheng KL, Figueroa-Balderas R, Aktas H, Ashrafi H, Pons C, Fernández-Muñoz R, Vicente A, Lopez-Baltazar J, Barry CS, Liu Y, Chetelat R, Granell A, Van Deynze A, Giovannoni JJ, Bennett AB (29 June 2012). "Uniform ripening Encodes a Golden 2-like Transcription Factor Regulating Tomato Fruit Chloroplast Development". Science. 336 (6089): 1711–1715. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1711P. doi:10.1126/science.1222218. PMID 22745430. S2CID 23517955.

- ↑ Kolata, Gina (28 June 2012). "Flavor Is Price of Scarlet Hue of Tomatoes, Study Finds". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ↑ Cocaliadis, Maria Florencia; Fernández-Muñoz, Rafael; Pons, Clara; Orzaez, Diego; Granell, Antonio (10 April 2014). "Increasing tomato fruit quality by enhancing fruit chloroplast function. A double-edged sword?". Journal of Experimental Botany. 65 (16): 4589–4598. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru165. hdl:10251/79375. PMID 24723405.

- 1 2 Klee, Harry J.; Tieman, Denise M. (2018). "The genetics of fruit flavour preferences". Nature. 19 (6): 347–356. doi:10.1038/s41576-018-0002-5. PMID 29563555. S2CID 736072.

- 1 2 Stevens, M. Allen (1986). "Inheritance of Tomato Fruit Quality Components". Plant Breeding Reviews. Vol. 4. Westport, CT: Avi Publishing Company. pp. 273–311. doi:10.1002/9781118061015.ch9. ISBN 9781118061015.

- ↑ Chaerani, Reni; Voorrips, Roeland E. (2006). "Tomato early blight (Alternaria solani): the pathogen, genetics, and breeding for resistance". Journal of General Plant Pathology. 72 (6): 335–347. doi:10.1007/s10327-006-0299-3. S2CID 36002406.

- ↑ "tomahuac". Nahuatl Dictionary. Wired Humanities Projects. Archived from the original on 6 December 2014.

- ↑ "English definition of 'tomato'". Cambridge Dictionaries Online. Cambridge University Press. 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ↑ Peet, M. "Crop Profiles – Tomato". Archived from the original on 26 November 2009. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ↑ "Are there different types of tomato leaves?". IVillage. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ↑ Acquaah, G. (2002). Horticulture: Principles and Practices. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-033125-0.

- ↑ Mark Abadi (26 May 2018). "A tomato is actually a fruit — but it's a vegetable at the same time". Business Insider. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ↑ Muños S, Ranc N, Botton E, Bérard A, Rolland S, Duffé P, Carretero Y, Le Paslier MC, Delalande C, Bouzayen M, Brunel D, Causse M (August 2011). "Increase in tomato locule number is controlled by two single-nucleotide polymorphisms located near WUSCHEL". Plant Physiol. 156 (4): 2244–54. doi:10.1104/pp.111.173997. PMC 3149950. PMID 21673133.

- ↑ "Selecting Tomatoes for the Home Garden". University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ↑ Lee, Eunkyung; Sargent, Steven A.; Huber, Donald J. (2007). "Physiological Changes in Roma-type Tomato Induced by Mechanical Stress at Several Ripeness Stages". HortScience. 42 (5): 1237–1242. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.42.5.1237.

- ↑ "Welcome to nginx!". gardenersworld.com. Gardeners' World Magazine. 24 March 2019. Archived from the original on 3 January 2023. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ↑ "Lycopersicon esculentum". International Plant Name Index. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.

- ↑ "International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants". International Association for Plant Taxonomy. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ↑ Peralta, I. E.; Spooner, D. M. (2001). "Granule-bound starch synthase (GBSSI) gene phylogeny of wild tomatoes (Solanum L. section Lycopersicon (Mill.) Wettst. subsection Lycopersicon)". American Journal of Botany. 88 (10): 1888–1902. doi:10.2307/3558365. JSTOR 3558365. PMID 21669622.

- ↑ Jacobsen, E.; Daniel, M. K.; Bergervoet-van Deelen, J. E. M.; Huigen, D. J. & Ramanna, M. S. (1994). "The first and second backcross progeny of the intergeneric fusion hybrids of potato and tomato after crossing with potato". Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 88 (2): 181–186. doi:10.1007/BF00225895. PMID 24185924. S2CID 1015489.

- ↑ Mueller, L. "International Tomato Genome Sequencing Project". Sol Genomics Network. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ↑ Ramanujan, K. (30 January 2007). "Tomato genome project gets $1.8M". News.cornell.edu. Archived from the original on 13 July 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ↑ "Tomato Genome Shotgun Sequence Prerelease".

- ↑ Sato, S.; Tabata, S.; Hirakawa, H.; et al. (2012). "The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution". Nature. 485 (7400): 635–641. Bibcode:2012Natur.485..635T. doi:10.1038/nature11119. PMC 3378239. PMID 22660326.

- ↑ Su, Xiao; Wang, Baoan; Geng, Xiaolin; et al. (15 December 2021). "A high-continuity and annotated tomato reference genome". BMC Genomics. 22 (1): 898. doi:10.1186/s12864-021-08212-x. ISSN 1471-2164. PMC 8672587. PMID 34911432.

- ↑ Tomato genome is sequenced for the first time Archived 4 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Rdmag.com. Retrieved on 5 September 2013.

- ↑ Redenbaugh, K.; Hiatt, B.; Martineau, B.; Kramer, M.; Sheehy, R.; Sanders, R.; Houck, C.; Emlay, D. (1992). Safety Assessment of Genetically Engineered Fruits and Vegetables: A Case Study of the Flavr Savr Tomato. CRC Press. p. 288.

- ↑ Michaels, Tom; Clark, Matt; Hoover, Emily; Irish, Laura; Smith, Alan; Tepe, Emily (20 June 2022). "Chapter 8.1 Fruit Morphology". In Tepe, Emily (ed.). The Science of Plants. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. ISBN 9781946135872.

- ↑ "Is a Tomato a Fruit or a Vegetable?". Fruit or Vegetable?. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ↑ "Confusing Items". Fruit or Vegetable?. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ↑ Nix v. Hedden, 149 U.S. 304 (1893).

- ↑ "Processing tomatoes" (PDF). Commodity Fact Sheet. California Foundation for Agriculture in the Classroom. September 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ "Mortgage Lifter Tomato Seeds". www.ufseeds.com. 2021. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ↑ Nowakowska, Marzena; et al. (3 October 2014), "Appraisal of artificial screening techniques of tomato to accurately reflect field performance of the late blight resistance", PLOS ONE, 9 (10): e109328, Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j9328N, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109328, PMC 4184844, PMID 25279467

- ↑ Pfleger, F. L.; Zeyen, R. J. (2008). "Tomato-Tobacco Mosaic Virus Disease". University of Minnesota Extension. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- 1 2 Fitzpatrick, Connor R.; Salas-González, Isai; Conway, Jonathan M.; Finkel, Omri M.; Gilbert, Sarah; Russ, Dor; Teixeira, Paulo José Pereira Lima; Dangl, Jeffery L. (8 September 2020). "The Plant Microbiome: From Ecology to Reductionism and Beyond". Annual Review of Microbiology. Annual Reviews. 74 (1): 81–100. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-022620-014327. ISSN 0066-4227. PMID 32530732. S2CID 219621296.

- ↑ Hahn, J.; Fetzer, J. (2009). "Slugs in Home Gardens". University of Minnesota Extension. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ↑ "Aculops lycopersici (tomato russet mite)". Wallingford, UK: Invasive Species Compendium, Centre for Agriculture and Biosciences International. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- ↑ Narvaez-Vasquez, J.; Orozco-Cardenas, M. L. (2008). "15 Systemins and AtPeps: Defense-related Peptide Signals". In Schaller, A. (ed.). Induced Plant Resistance to Herbivory. ISBN 978-1-4020-8181-1.

- ↑ Tomato Casual » Boost Your Tomatoes with Companion Planting! – Part 1 Archived 1 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Tomatocasual.com (6 May 2008). Retrieved on 5 September 2013.

- ↑ Vegetable Garden Companion Planting – Plant Tomatoes, Borage, and Squash Together Archived 29 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Organicgardening.about.com (16 July 2013). Retrieved on 5 September 2013.

- ↑ Bomford, Michael (May 2009). "Do Tomatoes Love Basil but Hate Brussels Sprouts? Competition and Land-Use Efficiency of Popularly Recommended and Discouraged Crop Mixtures in Biointensive Agriculture Systems". Journal of Sustainable Agriculture. 33 (4): 396–417. doi:10.1080/10440040902835001. S2CID 51900856. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ↑ Bomford, Michael (May 2004), Yield, Pest Density, and Tomato Flavor Effects of Companion Planting in Garden-scale Studies Incorporating Tomato, Basil, and Brussels Sprout, West Virginia University Libraries

- ↑ Takasugi, Mitsuo; Yachida, Youichi; Anetai, Masaki; Masamune, Tadashi; Kegasawa, Kazuo (1975). "Identification of Asparagusic Acid As a Nematicide Occurring Naturally in the Roots of Asparagus". Chemistry Letters. 4 (1): 43–4. doi:10.1246/cl.1975.43.

- ↑ Ploeg, Antoon (2000). "Effects of amending soil with Tagetes patula cv. Single Gold on Meloidogyne incognita infestation of tomato". Nematology. 2 (5): 489–93. doi:10.1163/156854100509394.

- ↑ Hooks, Cerruti R.R; Wang, Koon-Hui; Ploeg, Antoon; McSorley, Robert (2010). "Using marigold (Tagetes spp.) as a cover crop to protect crops from plant-parasitic nematodes". Applied Soil Ecology. 46 (3): 307–20. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2010.09.005.

- ↑ Natarajan, N; Cork, A; Boomathi, N; Pandi, R; Velavan, S; Dhakshnamoorthy, G (2006). "Cold aqueous extracts of African marigold, Tagetes erecta for control tomato root knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita". Crop Protection. 25 (11): 1210–3. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2006.03.008.

- 1 2 Sharma, V. P. (2012). Nature at Work – the Ongoing Saga of Evolution. Springer. p. 41. ISBN 978-81-8489-991-7.

- ↑ Frankie, Gordon; Thorp, Robbin; Coville, Rollin; barbara, Ertter; California Native Plant Society (2014). California bees & blooms : a guide for gardeners and naturalists. Berkeley, CA: Heydey. ISBN 9781597142946.

- ↑ Stassen NY, Logsdon JM, Vora GJ, Offenberg HH, Palmer JD, Zolan ME (1997). "Isolation and characterization of rad51 orthologs from Coprinus cinereus and Lycopersicon esculentum, and phylogenetic analysis of eukaryotic recA homologs" (PDF). Current Genetics. 31 (2): 144–157. doi:10.1007/s002940050189. PMID 9021132. S2CID 1472500. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2010.

- ↑ Jones, J. Benton. "Growing in the Greenhouse". Growing Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ↑ Bittman, Mark (14 June 2011). "The True Cost of Tomatoes". The New York Times.

- ↑ Bittman, Mark (17 August 2013). "Not All Industrial Food Is Evil". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ Bruening, G.; Lyons, J.M. (2000). "The case of the FLAVR SAVR tomato". California Agriculture. University of California, Agriculture and Natural Resources. 54 (4): 6–7. doi:10.3733/ca.v054n04p6.

- 1 2 "FAOSTAT: Production-Crops, 2012 data". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2014. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ↑ "FAOSTAT: Production-Crops, 2012 data", Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, August 2014

- ↑ "Curiosities of I-5, facts about King and the benefits of volunteers". Chester Progressive. 16 January 2008.

- ↑ A World Record Breaker Archived 31 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Nutriculture.com. Retrieved on 5 September 2013.

- ↑ "Most tomatoes harvested from one plant in one year". Guinness World Records. 20 April 2006. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ↑ The country's only single vine "tomato tree" growing in The Land pavilion at Epcot. Walt Disney World News

- ↑ "Tomato production in 2020, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ↑ Barceloux, D. G. (2009). "Potatoes, Tomatoes, and Solanine Toxicity (Solanum tuberosum L., Solanum lycopersicum L.)". Disease-a-Month. 55 (6): 391–402. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2009.03.009. PMID 19446683.

- 1 2 "Executive Summary Chaconine and Solanine: 6.0 through 8.0" (PDF). NIH. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2014.

- ↑ Brevitz, B. (2004). Hound Health Handbook: The Definitive Guide to Keeping your Dog Happy. Workman Publishing Company. p. 404. ISBN 978-0-7611-2795-6.

- ↑ "A selection of North American tomato related outbreaks from 1990–2005". Food Safety Network. 30 October 2006. Archived from the original on 26 January 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ↑ "CDC Probes Salmonella Outbreak, Health Officials Say Bacteria May Have Spread Through Some Form Of Produce". CBS News. 30 October 2006. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ↑ "Tomatoes taken off menus". Calgary Herald. 11 June 2008. Archived from the original on 25 August 2011. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ↑ Oruna-Concha, Maria-Jose; Methven, Lisa; Blumenthal, Heston; Young, Christopher; Mottram, Donald (11 July 2007). "Differences in Glutamic Acid and 5'-Ribonucleotide Contents between Flesh and Pulp of Tomatoes and the Relationship with Umami Taste". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 55 (14): 5776–80. doi:10.1021/jf070791p. PMID 17567148.

- ↑ Parnell, Tracy L.; Suslow, Trevor V.; Harris, Linda J. (March 2004). "Tomatoes:Safe Methods to Store, Preserve, and Enjoy" (PDF). ANR Catalog. University of California: Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ "Selecting, Storing and Serving Ohio Tomatoes, HYG-5532-93" (PDF). Ohio State University. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ↑ How To Cook. Cooks Illustrated (1 July 2008). Retrieved on 5 September 2013.

- ↑ Store Tomatoes Stem-End Down to Keep Them from Rotting Too Quickly. Lifehacker.com. Retrieved on 5 September 2013.

- ↑ "Vegetables". Canadian Produce Marketing Association Website. Canadian Produce Marketing Association. Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ Collins, Edward J.; Bowyer, Cressida; Tsouza, Audrey; Chopra, Mridula (4 February 2022). "Tomatoes: An Extensive Review of the Associated Health Impacts of Tomatoes and Factors That Can Affect Their Cultivation". Biology. MDPI AG. 11 (2): 239. doi:10.3390/biology11020239. ISSN 2079-7737. PMC 8869745.

- ↑ Burton-Freeman B, Sesso HD (2014). "Whole food versus supplement: comparing the clinical evidence of tomato intake and lycopene supplementation on cardiovascular risk factors". Adv Nutr. 5 (5): 457–85. doi:10.3945/an.114.005231. PMC 4188219. PMID 25469376.

- ↑ Hackshaw-McGeagh LE, Perry RE, Leach VA, Qandil S, Jeffreys M, Martin RM, Lane JA (2015). "A systematic review of dietary, nutritional, and physical activity interventions for the prevention of prostate cancer progression and mortality". Cancer Causes Control. 26 (11): 1521–50. doi:10.1007/s10552-015-0659-4. PMC 4596907. PMID 26354897.

- ↑ Schneeman, Barbara O (8 November 2005). "Qualified Health Claims: Letter Regarding "Tomatoes and Prostate, Ovarian, Gastric and Pancreatic Cancers (American Longevity Petition)" (Docket No. 2004Q-0201)". Labeling and Nutrition. Letter to Jonathan W. Emord, Esq., Emord & Associates, P.C. US Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017.

- ↑ European Food Safety Authority (2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to lycopene and protection of DNA, proteins and lipids from oxidative damage (ID 1608, 1609, 1611, 1662, 1663, 1664, 1899, 1942, 2081, 2082, 2142, 2374), protection of the skin from UV-induced (including photo-oxidative) damage (ID 1259, 1607, 1665, 2143, 2262, 2373), contribution to normal cardiac function (ID 1610, 2372), and maintenance of normal vision (ID 1827) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006". EFSA Journal. 9 (4): 2031. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2031.

- ↑ Varela, L. G.; Bernays, E. A. (1 July 1988). "Behavior of newly hatched potato tuber moth larvae, Phthorimaea operculella Zell. (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae), in relation to their host plants". Journal of Insect Behavior. 1 (3): 261–275. doi:10.1007/BF01054525. S2CID 19062069.

- ↑ Buendia, Luis; Wang, Tongming; Girardin, Ariane; Lefebvre, Benoit (April 2016). "The LysM receptor‐like kinase Sl LYK 10 regulates the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in tomato". New Phytologist. 210 (1): 184–195. doi:10.1111/nph.13753. PMID 26612325.

- ↑ "Spain's tomato fighters see red". ITV. 30 August 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2009.

- ↑ Morin, XK (2008). "Genetically modified food from crops: progress, pawns, and possibilities". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 392 (3): 333–40. doi:10.1007/s00216-008-2313-4. PMC 2556401. PMID 18704376.

Further reading

- David Gentilcore. Pomodoro! A History of the Tomato in Italy (Columbia University Press, 2010), scholarly history

- Tieman, D; Bliss, P; McIntyre, LM; Blandon-Ubeda, A; Bies, D; Odabasi, AZ; Rodríguez, GR; van der Knaap, E; Taylor, MG; Goulet, C; Mageroy, MH; Snyder, DJ; Colquhoun, T; Moskowitz, H; Clark, DG; Sims, C; Bartoshuk, L; Klee, HJ (5 June 2012). "The Chemical Interactions Underlying Tomato Flavor Preferences". Current Biology. 22 (11): 1035–1039. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.016. PMID 22633806.

External links

- Tomato Genome Sequencing Project – Sequencing of the twelve tomato chromosomes.

- Tomato core collection database – Phenotypes and images of 7,000 tomato cultivars

(NRCS_Photo_Gallery).jpg.webp)