Drvar

Дрвар | |

|---|---|

Town and municipality | |

Drvar | |

| |

| Coordinates: 44°22′27″N 16°23′04″E / 44.37417°N 16.38444°E | |

| Country | |

| Entity | Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Canton | Canton 10 |

| Geographical region | Bosanska Krajina |

| Government | |

| • Municipal mayor | Dušica Runić (SNSD) |

| Area | |

| • Town and municipality | 589.3 km2 (227.5 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 480 m (1,570 ft) |

| Population (2013 census) | |

| • Town and municipality | 7,036 |

| • Density | 12/km2 (31/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,730 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +387 34 |

| Website | www |

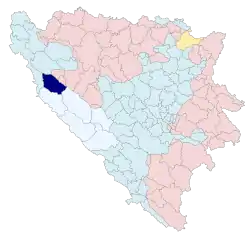

Drvar (Serbian Cyrillic: Дрвар, pronounced [dř̩ʋaːr]) is a town and municipality located in Canton 10 of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, an entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The 2013 census registered the municipality as having a population of 7,036.[1] It is situated in western Bosnia and Herzegovina, on the road between Bosansko Grahovo and Bosanski Petrovac, also near Glamoč.

Drvar lies in the vast valley, the southeastern part of Bosanska Krajina, between the Osječanica, Klekovača, Vijenca and Šator mountains of the Dinaric Alps. The southeast side of boundary extends from the Šator over Jadovnika, Uilice and descends to Lipovo and the Una River.

This extremely hilly region comprising the town of Drvar and the numerous outlying villages covers approximately 1,030 square kilometers (640 square miles). The town itself is mainly spread out from the left side of the river Unac, and its elevation is approximately 480 meters (1,574 feet).

Name

The word Drvar stems from the Slavic word drvo which means 'wood'. During the period of SFR Yugoslavia, Drvar was named Titov Drvar in honor of Josip Broz Tito.

History

Early history

The first writings on Drvar date back to the 9th century. In the first half of the 16th century (approximately 1530) residents of this area, under the leadership of a Vojnović from Glamoč, migrated to the surroundings of Zagreb (Metlika Zumberak and four surrounding villages). The greater area was populated in Roman Times as evidenced by the remains of Roman roads and.

Austro-Hungarian Rule

In 1878 Drvar, along with the rest of Bosnia, was subjugated to Austro-Hungarian rule. Around 1893 German industrialist Otto von Steinbeis leased the right to exploit fir and spruce forests in the mountains of Klekovača, Lunjevače, Srnetica and Osječenica. Steinbeis operated in the area until 1918 when, after the First World War, the company was taken over by the new Yugoslav state. During the 25 years that Steinbeis operated in the area, he created a complete infrastructure for processing forest products including the construction of modern lumber mills in Drvar and Dobrljin, and the construction of a network of roads and 400 km of narrow-gauge railway, and telephone and telegraph lines.[2] During this time Drvar grew into an industrial town employing approximately 2,800 persons in which homes, hospitals, restaurants, cafe and retails shops were built. Additional factories appeared in Drvar, including a cellulose factory opened by Alphons Simunius Blumer.

Eventually, poor labor conditions led to the first organized strikes in Drvar in 1906. These strikes continued until 1911 when the Austro-Hungarian Empire banned all such activities.

20th century

In 1918 the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed, which was then followed by the rise of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, but this did not help the plight of the workers in Drvar, who became better organised and rose up to strike again in 1921.

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

From 1929 to 1941, Drvar was part of the Vrbas Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In 1932, an economic crisis resulted in the layoff of 2,000 workers.

World War II

On 10 April, Ustaše, aligned with Nazi Germany, declared the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) and claimed as part of its territory the entire area known as Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Drvar, this resulted in the beginning of the presence of the Ustaše government, the movement chiefly responsible for the World War II Holocaust in the Independent State of Croatia in which Serbs, Jews, Roma, Croat and Bosniak resistance members and political opponents were sent to concentration camps and killed. In the beginning the Ustaše contingent in Drvar consisted of the Croatian population residing in Drvar, but they were soon reinforced by others who came from outside Drvar.

In June 1941 Ustaše arrested a large group of prominent Drvar citizens, and took them to Risovac near Bosanski Petrovac, where they were tortured, killed and thrown into a pit. After Ustaše imprisoned all Serb men from Drvar during June and July 1941, they began with preparation to imprison and kill all Serbs from Drvar, regardless of their age and sex, including all women and children.[3]

The genocidal activities of the Ustaše forced targeted Serb population to organize an uprising known as Drvar uprising. The rebels were organized into Kamenički, Javorje, Crljivičko-zaglavički, Boboljusko-cvjetnički, Trubarski, Mokronog and Tičevski and Grahovo area Grahovsko-resanovski guerrilla detachments.

In more recent history, Drvar is perhaps most famous as the location of a daring airdrop raid on Drvar, codenamed "Operation Rösselsprung", on 25 May 1944, by Nazi German invaders, in an attempt to assassinate Tito. Tito, the main Partisan commander, was sheltered in the Partisan General Staff headquarters in what is now called "Tito's Cave" in the hills near Drvar at the time.

During the 4 years and 1 months of the war, Drvar was under occupation for just 390 days. 767 Drvar civilians were killed and only 13 pre-war houses still stood. Approximately 93% of the infrastructure of the town was destroyed, and the livestock population had been reduced by more than 80%.

Drvar was first occupied by the German army in April 1941, followed shortly thereafter by the Italians. Drvar continued to experience fierce fighting through mid-1942 when the last of the German and Italian forces were expelled. The Germans re-entered Drvar in 1943 and left it a burned ruin when they departed.

During the summer 1941, Chetniks expelled and killed Croat and Catholic civilians in Drvar area. The most significant event was the Trubar massacre, a civilian massacre committed by Chetniks on 27 July 1941.[4][5]

SFR Yugoslavia

In the years following the war, Drvar was rebuilt, its timber industry restored, and new metal, fabrication, and carpet industries developed. Eventually, electricity was brought to outlying villages. Over time, it became a tourist destination attracting approximately 200,000 visitors a year, primarily to Tito's Cave, and on November 24, 1981, Drvar changed its name to Titov Drvar.

Bosnian War

In September 1995, Drvar, as well as some other municipalities, was taken over by Croatian forces, and the Serb population fled. Many of them moved to Banja Luka. During this period, Drvar was nearly deserted. Leading up to 1995, Drvar was populated almost entirely by Bosnian Serbs. During the Bosnian War between 1992 and 1995, Drvar was controlled by what is now called the Republika Srpska.

On 3 August 1995, the Croatian Armed Forces with the help of Bosnian Croats began shelling Drvar, from the mountain of Šator. Two Drvar citizens were killed and older men and women began to evacuate to Petrovac. One day later, the Croatian Government armed forces began "Operation Storm", called by European Union Special Envoy to the Former Yugoslavia Carl Bildt, "the most efficient ethnic cleansing we've seen in the Balkans",[6] in the "Dalmatinska zagora" region of Croatia, and columns of hundreds of thousands of refugees in cars, on tractors, wagons and on foot began to pass through Drvar as they fled their homes in Croatia. The shelling on the outlying areas of Drvar by Croatian Government forces was renewed and continued for days.

Aftermath

In late 1995, after the Dayton Peace Accord was signed, Drvar became part of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, after which Croat politicians enticed up to 6,000 Bosnian Croats, mainly displaced persons from central Bosnia, to move to Drvar, by promising such things as jobs and keys to vacant homes. A further 2,500 Croat HVO troops and their families were stationed there, also occupying the homes of displaced Bosnian Serb citizens.[7] This drastically changed the population and from 1995 to 1999 the population was primarily Croatian.

In 1996, small numbers of Serbs began to try to return to their homes but faced harassment and discrimination by the Croats. The return continued nonetheless despite the ongoing looting and burning of their homes in 1996–1998.[8]

In 1998, Croat opposition to the return of displaced Bosnian Serb citizens culminated in riots and murders. Buildings and houses were torched, United Nations International Police Task Force personnel, SFOR personnel and Mayor, Mile Marceta (elected with Serb refugee votes) were attacked, and two displaced elderly Serbs who had recently returned to Drvar were murdered.[7][9]

Much of the damage done to the town of Drvar was done not during the war, but during its subsequent occupation by Croat civilians and military personnel as the homes and business of displaced Bosnian Serbs attempting to return to Drvar were looted and burned. The local government and companies, the few that exist, are dominated by the Croats, and Serbs have difficulty finding employment.

Modern

Since the end of the Bosnian War, about 5,000 Bosnian Serb residents have returned to Drvar. However, unemployment in the town stands at 80% and many residents blame the government of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina for the poor economic situation.[10][11]

In September 2019, the President of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić made an official visit to Drvar, along with the Serb Member of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina Milorad Dodik.[12]

Drvar is a member of the Alliance of Serb Municipalities.

Settlements

Aside from the town of Drvar, the following settlements comprise the municipality:

Demographics

Population

| Population of settlements – Drvar municipality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Settlement | 1961. | 1971. | 1981. | 1991. | 2013. | |

| Total | 18.811 | 20,064 | 17,983 | 17,126 | 7,560 | |

| 1 | Drvar | 3,646 | 6,417 | 7,063 | 8,053 | 3,730 |

| 2 | Drvar Selo | 844 | 490 | |||

| 3 | Mokronoge | 646 | 298 | |||

| 4 | Šipovljani | 998 | 478 | |||

| 5 | Trninić Brijeg | 382 | 232 | |||

| 6 | Vrtoče | 1,582 | 825 | |||

Ethnic composition

| Ethnic composition – Drvar town | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013. | 1991. | 1981. | 1971. | 1961. | ||||

| Total | 3,730 (100,0%) | 8,053 (100,0%) | 7,063 (100,0%) | 6,417 (100,0%) | 3,646 (100,0%) | |||

| Serbs | 3,160 (84,72%) | 7,693 (95,53%) | 6,006 (85,03%) | 6,056 (94,37%) | 3,645 (99,972%) | |||

| Croats | 527 (14,13%) | 24 (0,298%) | 42 (0,595%) | 98 (1,527%) | 95 (2,606%) | |||

| Others | 33 (0,885%) | 48 (0,596%) | 18 (0,255%) | 50 (0,779%) | 35 (0,960%) | |||

| Bosniaks | 10 (0,268%) | 29 (0,360%) | 22 (0,311%) | 115 (1,792%) | 33 (0,905%) | |||

| Yugoslavs | 259 (3,216%) | 961 (13,61%) | 66 (1,029%) | 18 (0,494%) | ||||

| Albanians | 11 (0,156%) | 16 (0,249%) | ||||||

| Slovenes | 3 (0,042%) | 7 (0,109%) | ||||||

| Montenegrins | 9 (0,140%) | |||||||

| Ethnic composition – Drvar municipality | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013. | 1991. | 1981. | 1971. | 1961. | ||||

| Total | 7,560 (100,0%) | 17,126 (100,0%) | 17,983 (100,0%) | 20,064 (100,0%) | 18,811 (100,0%) | |||

| Serbs | 6,420 (91,25%) | 16,608 (96,98%) | 15,896 (88,39%) | 19,496 (97,17%) | 18,362 (97,613%) | |||

| Croats | 552 (7,845%) | 33 (0,193%) | 62 (0,345%) | 141 (0,703%) | 185 (0,968%) | |||

| Others | 53 (0,753%) | 68 (0,397%) | 32 (0,178%) | 101 (0,503%) | 61 (0,324%) | |||

| Bosniaks | 11 (0,156%) | 33 (0,193%) | 26 (0,145%) | 213 (1,062%) | 34 (0,181%) | |||

| Yugoslavs | 384 (2,242%) | 1 949 (10,84%) | 74 (0,369%) | 169 (0,898%) | ||||

| Albanians | 12 (0,067%) | 16 (0,080%) | ||||||

| Slovenes | 4 (0,022%) | 7 (0,035%) | ||||||

| Montenegrins | 2 (0,011%) | 16 (0,080%) | ||||||

Economy

Drvar was already well known in the Austrian-Hungarian era due to the high-quality wood coming from that area. The Drvar area is still one of the largest logging and wood-processing environments in BiH. One of the major problems in this area is the widespread corruption connected to this wood-processing industry. It is estimated that during 2004 about 110,000m 3 of wood 'disappeared'. Average price of 1m 3 of timber (second class) is about 100 BAM (100 Convertible Mark=49.5 Euros).

Features

A "Desant na Drvar" is a movie made about the German attack on Drvar. There are still some locations in area, which were heavily fought over in that period, that still seem to be untouched by time.

Famous landmarks include "Tito's Cave" and the so-called "Citadel". At the latter mentioned location one can find an Austrian-Hungarian cemetery (in a very poor state) which may contain some (unknown) number of German soldiers buried after the attack of 1944. On this spot there is also a Roman road sign (+/- 100 AD). Another one can be found on the way to Bosanski Petrovac near Zaglavica.

Drvar is also renowned for its local rakija, a type of plum or cranberry brandy, originating in Serbia but popular all over the Balkans.

Notable people

- Saša Adamović, doctor of cryptology

- Andrea Arsović, sports shooting

- Marija Bursać, National Hero of Yugoslavia

- Mika Bosnić, national hero

- Nikola Špirić, Former Prime Minister of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Ilija Kajtez, sociologist, philosopher, educator, writer, and retired officer

- Radomir Kovačević, Olympic medalist in judo

- Dejan Matić, singer

- Saša Matić, singer

- Petar Pećanac, first man who climbed Mount Everest from BIH and Republika Srpska in 2007

- Milan Rodić, professional football player

- Mirko Srdić, musician

See also

References

- ↑ "Naseljena Mjesta 1991/2013" (in Bosnian). Statistical Office of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ↑ Archived 2011-10-06 at the Wayback Machine, Helga Berdan: Die Machtpolitik Österreich-Ungarns und der Eisenbahnbau in Bosnien-Herzegowina 1872–1914, Magisterarbeit, Wien 2008

- ↑ (Dedijer & Miletić 1989, p. 221):"Posle odvođenja Srba muškaraca iz Drvara u toku juna i jula 1941 god počele su ustaške vlasti vršiti pripreme za odvođenje i ubistvo svih Srba iz Drvara bez razlike u pogledu pola i starosti: bilo je predviđeno da se imaju pobiti i sve žene i sva deca."

- ↑ Čutura, Vlado. "Rađa se novi život na mučeničkoj krvi". Glas Koncila. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Vukšić, Tomo. ""Dan ustanka" - ubojstvo župnika iz Drvara i Bosanskog Grahova". Katolički tjednik. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- ↑ Pearl, Daniel (2002), At Home in the World: Collected Writings from The Wall Street Journal, Simon and Schuster, p. 224 Archived 2016-10-31 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 0-7432-4415-X

- 1 2 International Crisis Group, Impunity in Drvar Archived February 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, 20 August 1998

- ↑ International Crisis Group, House Burnings: Obstruction of the Right to Return to Drvar Archived February 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, 16 June 1997, accessed April 2011

- ↑ UNHCR, Drvar: Bosnia's Don Quixote Archived 2011-09-14 at the Wayback Machine, Refugees vol 1, 1999, p 114, accessed April 2011

- ↑ "Bosnia town holds 'funeral' to protest at unemployment". BBC. 4 March 2013. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ "Dejtonska sudbina Drvara". RTS. 3 August 2013. Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ↑ "Vučić: Jedinstveni za opstanak; Ne mešam se u unutrašnje stvari BiH". b92.net (in Serbian). Tanjug. 13 September 2019. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

Sources

- Dedijer, Vladimir; Miletić, Antun (1989). Proterivanje Srba sa ognjišta 1941-1944: svedočanstva. Prosveta. ISBN 9788607004508.