| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Ticlid |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a695036 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | >80% |

| Protein binding | 98% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 12 hours (single dose) 4–5 days (repeated dosing) |

| Excretion | Kidney and fecal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.054.071 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

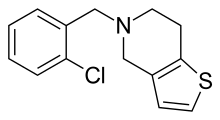

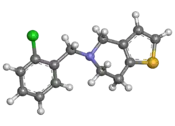

| Formula | C14H14ClNS |

| Molar mass | 263.78 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Ticlopidine, sold under the brand name Ticlid, is a medication used to reduce the risk of thrombotic strokes.[1] It is an antiplatelet drug in the thienopyridine family which is an adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor inhibitor. Research initially showed that it was useful for preventing strokes and coronary stent occlusions. However, because of its rare but serious side effects of neutropenia and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura it was primarily used in patients in whom aspirin was not tolerated, or in whom dual antiplatelet therapy was desirable. With the advent of newer and safer antiplatelet drugs such as clopidogrel and ticagrelor, its use remained limited.

It was patented in 1973 and approved for medical use in 1978.[5]

Medical uses

Ticlopidine is indicated for the prevention of strokes and when combined with aspirin, for people with a new coronary stent to prevent closure.[1]

Stroke

Ticlopidine is considered a second-line option for the prevention of thrombotic strokes among patients who have previously had a stroke or TIA. Studies have shown that it is superior to aspirin in the prevention of death or future strokes. However, it also has more frequent and serious side effects compared to aspirin, so it is reserved for those patients that cannot take aspirin.[6]

Heart disease

When a patient needs to have a stent placed in one of the vessels around their heart, it is important that that stent stay open to keep blood flowing to the heart. Therefore, patients with stents must take medications after the procedure to help maintain that blood flow. Ticlopidine, taken together with aspirin, is FDA approved for this purpose, and in studies it has been shown to work better than aspirin alone or aspirin with an anticoagulant.[7][8] However, ticlopidine’s serious side effects make it less useful than its cousin, clopidogrel.[9] Current recommendations no longer recommend ticlopidine’s use.[10]

Contraindications

The use of ticlopidine is contraindicated in anyone with:

- Increased risk of bleeding (i.e. frequent falls, gastrointestinal bleeds)

- History of hematological disease

- Severe liver disease

- History of allergic reaction to ticlopidine or any thienopyridine drug such as clopidogrel

Because of the increased risk of bleeding, patients taking ticlopidine should discontinue the medication 10–14 days before surgery.[1]

Adverse effects

The most serious side effects associated with ticlopidine are those that affect the blood cells, although these life-threatening complications are relatively rare. The most common side effects include:[1]

- Diarrhea

- Nausea

- Dyspepsia

- Rash

- Abdominal pain

Ticlopidine may also cause an increase in cholesterol, triglycerides, liver enzymes, and bleeding.[1]

Hematological

Use of ticlopidine has been associated with neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), and aplastic anemia. Because of this risk, patients who are started on ticlopidine are typically monitored with blood tests to test their cell counts every two weeks for the first three months.[1]

Pregnancy and lactation

Ticlopidine is a FDA pregnancy risk category B. There have been no studies done in humans. Studies in rats show that high drug levels could cause toxicity in both mother and fetus, but there are no known birth defects associated with its use.[1]

There have been no studies to test whether ticlopidine goes into breast milk. Studies in rats have shown that it is passed in rats’ milk.[1]

Interactions

Ticlopidine interacts with several classes of medications. It increases the antiplatelet effects of aspirin and other NSAIDs.[1] Taking ticlopidine at the same time as antacids decreases the absorption of ticlopidine.[1] Ticlopidine inhibits liver CYP2C19[11] and CYP2B6[12] and thus can affect blood levels of medications metabolized by these systems.

Mechanism of action

Ticlopidine is a thienopyridine which, when metabolized by the body, irreversibly blocks the P2Y12 component of the ADP receptor on the surface of platelets. Without ADP, fibrinogen does not bind to the platelet surface, preventing platelets from sticking to each other.[1] By interfering with platelet function, ticlopidine prevents clots from forming on the inside of blood vessels.[13] Anti-platelet effects start within 2 days and reach their maximum by 6 days of therapy. Ticlopidine’s effects persist for 3 days after discontinuing ticlopidine although it may take 1–2 weeks for platelet function to return to normal, as the medication affects platelets irreversibly. Therefore, new platelets must be formed before platelet function normalizes.[1]

Pharmacokinetics

Ticlopidine is ingested orally with 80% bioavailability with rapid absorption. Even higher absorption can occur if ticlopidine is taken with food. It is metabolized by the liver with both renal and fecal elimination. Clearance is nonlinear and varies with repeated dosing. After the first dose the half life is 12.6 hours, but with repeated dosing the maximum half life is 4–5 days. Clearance is also slower in the elderly. The drug is 98% reversibly bound to proteins.[1]

Chemical properties

Ticlopidine's systemic name is 5-[(2-chlorophenyl)methyl]-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridine. Its molecular weight is 263.786 g/mol. It is a white crystalline solid. It is soluble in water and methanol and somewhat soluble in methylene chloride, ethanol, and acetone. It self buffers in water to a pH of 3.6.[1]

History

Ticlopidine was discovered in the 1970s in France by a team led by Fernand Eloy and including Jean-Pierre Maffrand at Castaigne SA that was trying to discover a new anti-inflammatory medication. Pharmacology developers noted that this new compound had strong anti-platelet properties.[14] Castaigne was acquired by Sanofi in 1973.[15] Starting in 1978 the drug was marketed in France under the brand name Ticlid for people at high risk for thrombotic events, who had just come out of heart surgery, were undergoing hemodialysis, had peripheral vascular disease, or who were otherwise at risk for strokes and ischemic heart disease.[14]

Ticlopidine was brought to market in the US by Syntex, which got the drug approved in 1991.[16] Syntex was acquired by the Roche group in 1994.[17] The first generic ticlopidine hydrochloride was FDA approved in 1999.[18] As of April 2015, Roche, Caraco, Sandoz, Par, Major, Apotex, and Teva had discontinued generic ticlopidine and no ticlopidine preparations were available in the US.[19]

Research

Soon after its release, studies regarding ticlopidine found it had the potential to be helpful for other diseases including peripheral vascular disease,[20] diabetic retinopathy,[21] and sickle cell disease.[22] However none had enough evidence for FDA approval. Due to the blood cell side effects associated with ticlopidine, researchers for treatments for these conditions have turned to other avenues.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Ticlopidine hydrochloride tablet, film coated". DailyMed. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ↑ "Ticlid (ticlopidine hydrochloride) tablets". DailyMed. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ↑ "Drug Approval Package: Ticlid (Ticlopidine Hydrochloride) NDA #19-979/S-018". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 December 1999. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ↑ "Active substance: ticlopidine" (PDF). List of nationally authorised medicinal products. European Medicines Agency. 14 January 2021.

- ↑ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 453. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ↑ Hass WK, Easton JD, Adams HP, Pryse-Phillips W, Molony BA, Anderson S, Kamm B (August 1989). "A randomized trial comparing ticlopidine hydrochloride with aspirin for the prevention of stroke in high-risk patients. Ticlopidine Aspirin Stroke Study Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 321 (8): 501–507. doi:10.1056/nejm198908243210804. PMID 2761587.

- ↑ Schömig A, Neumann FJ, Kastrati A, Schühlen H, Blasini R, Hadamitzky M, et al. (April 1996). "A randomized comparison of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy after the placement of coronary-artery stents". The New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (17): 1084–1089. doi:10.1056/nejm199604253341702. PMID 8598866.

- ↑ Leon MB, Baim DS, Popma JJ, Gordon PC, Cutlip DE, Ho KK, et al. (December 1998). "A clinical trial comparing three antithrombotic-drug regimens after coronary-artery stenting. Stent Anticoagulation Restenosis Study Investigators". The New England Journal of Medicine. 339 (23): 1665–1671. doi:10.1056/nejm199812033392303. PMID 9834303.

- ↑ Manolis AS, Tzeis S, Andrikopoulos G, Koulouris S, Melita H (July 2005). "Aspirin and clopidogrel: a sweeping combination in cardiology". Current Medicinal Chemistry - Cardiovascular & Hematological Agents. 3 (3): 203–19. doi:10.2174/1568016054368188. PMID 15974885.

- ↑ Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, Casey DE, Ganiats TG, Holmes DR, et al. (December 2014). "2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines". Circulation. 130 (25): e344–e426. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000134. PMID 25249585.

- ↑ Ha-Duong NT, Dijols S, Macherey AC, Goldstein JA, Dansette PM, Mansuy D (October 2001). "Ticlopidine as a selective mechanism-based inhibitor of human cytochrome P450 2C19". Biochemistry. 40 (40): 12112–12122. doi:10.1021/bi010254c. PMID 11580286.

- ↑ Turpeinen M, Tolonen A, Uusitalo J, Jalonen J, Pelkonen O, Laine K (June 2005). "Effect of clopidogrel and ticlopidine on cytochrome P450 2B6 activity as measured by bupropion hydroxylation". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 77 (6): 553–559. doi:10.1016/j.clpt.2005.02.010. PMID 15961986. S2CID 12520818.

- ↑ Katzung B, Masters S, Trevor A (2012). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology, 12th ed. pp. Chapter 34: Drugs Used in Disorders of Coagulation.

- 1 2 Maffrand JP (2012). "The story of clopidogrel and its predecessor, ticlopidine: Could these major antiplatelet and antithrombotic drugs be discovered and developed today?". Comptes Rendus Chimie. 15 (8): 737–743. doi:10.1016/j.crci.2012.05.006.

- ↑ Aftalion F (2001). "World War II and the Consequence for World Chemicals". A History of the International Chemical Industry. Chemical Heritage Foundation. p. 296. ISBN 9780941901291.

- ↑ Flores-Runk P, Raasch RH (September 1993). "Ticlopidine and antiplatelet therapy". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 27 (9): 1090–1098. doi:10.1177/106002809302700915. PMID 8219445. S2CID 45299169.

- ↑ Freudenheim M (3 May 1994). "Roche Set To Acquire Syntex". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Press release: Apotex First To Market Generic Version Of Ticlid®". July 6, 1999.

- ↑ "Ticlopidine Tablets". Resolved Shortages Bulletin. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. April 1, 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ↑ Kirstein P, Jogestrand T, Johnsson H, Olsson AG (August 1980). "Antiaggregatory, physiological and clinical effects of ticlopidine in subjects with peripheral atherosclerosis". Atherosclerosis. 36 (4): 471–480. doi:10.1016/0021-9150(80)90240-3. PMID 7417366.

- ↑ "Ticlopidine treatment reduces the progression of nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy. The TIMAD Study Group". Archives of Ophthalmology. 108 (11): 1577–1583. November 1990. doi:10.1001/archopht.1990.01070130079035. PMID 2244843.

- ↑ Cabannes R, Lonsdorfer J, Castaigne JP, Ondo A, Plassard A, Zohoun I (1984). "Clinical and biological double-blind-study of ticlopidine in preventive treatment of sickle-cell disease crises". Agents and Actions. Supplements. 15: 199–212. PMID 6385647.

External links

- "Ticlopidine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Ticlopidine hydrochloride". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.