| Thomson and Thompson | |

|---|---|

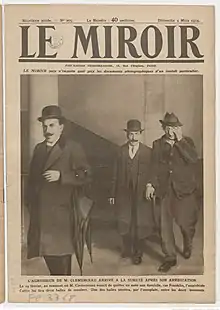

Thompson (left) and Thomson (right), from Cigars of the Pharaoh, by Hergé. Note the difference between their moustaches. | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Casterman (Belgium) |

| First appearance | Cigars of the Pharaoh (1934) The Adventures of Tintin |

| Created by | Hergé |

| In-story information | |

| Full name | Thomson and Thompson |

| Partnerships | List of main characters |

| Supporting character of | Tintin |

Thomson and Thompson (French: Dupont et Dupond [dy.pɔ̃])[1] are fictional characters in The Adventures of Tintin, the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé. They are two incompetent detectives who provide much of the comic relief throughout the series. While their different (albeit similar) surnames would suggest they are unrelated, they look like identical twins whose only discernible difference is the shape of their moustaches; Hergé twice calls them "brothers" in the original French-language text. They are afflicted with chronic spoonerisms, are extremely clumsy, thoroughly clueless, frequently arresting the wrong person (usually someone important). In spite of this, they somehow are entrusted with delicate missions.

The detective with the flat, drooping walrus moustache is Thompson and introduces himself as "Thompson, with a 'P', as in psychology" (or any such word in which the "P" is silent), while the detective with the flared, pointed moustache is Thomson, who often introduces himself as "Thomson, without a 'P', as in Venezuela."

Often, when one says something, the other adds "To be precise" (Je dirais même plus), but then repeats what the first said, only twisted around.[2][3]

Thomson and Thompson usually wear bowler hats and carry walking sticks, except when abroad: during these missions they insist on wearing the stereotypical costume of the country they are visiting, hoping to blend into the local population, but instead manage to dress in folkloric attire that actually makes them stand out.

The detectives were in part based on Hergé's father and uncle, identical twins who wore matching bowler hats while carrying matching walking sticks.[4]

Character history

In Tintin in America there are characters similar to Thomson and Thompson: two policemen who collide with each other, and an incompetent detective called Mike MacAdam.[5]

In Tintin in the Congo, Thomson and Thompson make only a brief one-panel appearance (although they did not appear in the original version). Their first contribution to the plot of a story comes in Cigars of the Pharaoh (originally published in 1934), where they first appear when they come into conflict with Tintin on board a ship where he and Snowy are enjoying a holiday cruise. When this adventure was first published they were referred to as X33 and X33A (X33 et X33 bis in French).[6][4] Here they show an unusually high level of cunning and efficiency, going to great lengths to rescue Tintin from the firing squad (in disguises that fool even Tintin) and saving Snowy from sacrifice. In this and two other early stories — The Blue Lotus and The Black Island — they spend most of their time, forced to follow official orders and faked evidence, in pursuit of Tintin himself for crimes he has not committed, the two noting in Blue Lotus that they never believed in Tintin's guilt even though they had to obey their orders. Except for their codenames, they remained nameless in the early adventures. It was not until King Ottokar's Sceptre, published in 1938, that Tintin mentions their definitive names when introducing them to Professor Alembick at the airport.

In his 1941 play Tintin in India: The Mystery of the Blue Diamond co-written with Jacques Van Melkebeke, Hergé named them as "Durant and Durand", although he later renamed them as "Dupont and Dupond".[7] When King Ottokar's Sceptre was serialised in Eagle for British readers in 1951, the characters were referred to as "Thomson and Thompson"; these names were later adopted by translators Leslie Lonsdale-Cooper and Michael Turner in their translation of the series into English for Methuen Publishing.[8]

While the original version of Cigars of the Pharaoh was published in 1932, the rewritten and redrawn version was issued in 1955, and was not published in English until 1971. This resulted in some chronological confusion for English-speaking readers of the Tintin series, which is why the text hints that Tintin already knows the pair, and is surprised at their unfriendly behaviour; however, in the original chronological sequence, this is indeed the first time they ever meet. In addition, Hergé retroactively added them to the 1946 colour version of the second Tintin story, Tintin in the Congo, in the background as Tintin embarks for what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[9]

Thomson and Thompson were originally only side characters but later became more important. In the re-drawings of the earlier books, especially The Black Island, the detectives gained their now-traditional mannerisms.

In Land of Black Gold, the detectives mistakenly swallow some mysterious pills used to adulterate fuel, that causes them to sprout immensely long beards and hair that change colour constantly and grow at a break-neck pace. The condition wears off by the end of this adventure, but it relapses in Explorers on the Moon, causing problems when Captain Haddock must continuously cut their hair, repeatedly switching back to re-cut floor length hair (and mustaches and beards) which all grow back in seconds. Frustrated at this, the captain exclaims "After all this, when they ask me what did I do on the rocket, I'll reply 'Me, you say? I was the barber!'"

In the 19 books following Cigars of the Pharaoh, Thomson and Thompson appear in 17 of them, not appearing in Tintin in Tibet or Flight 714 to Sydney. In some of these books their role is minor – the duo's appearance in The Shooting Star is confined to two panels; they appear briefly only at the beginning of The Broken Ear (before being tricked into closing the case in the belief that the stolen object has been returned when it was actually replaced by a fake); and are imprisoned and face execution on false charges in Tintin and the Picaros. During their other appearances, they serve as the official investigators into whatever crimes Tintin is currently investigating. Their final appearance was in Tintin and Alph-Art.

Inspiration and cultural impact

The detectives were in part based on Hergé's father Alexis and uncle Léon, identical twins who often took walks together wearing matching bowler hats while carrying matching walking sticks.[4] Another inspiration was a picture of two mustachioed, bowler-hatted, formally dressed detectives who were featured on the cover of the Le Miroir edition of 2 March 1919. They were shown escorting Emile Cottin, who had attacked Georges Clemenceau—one detective was handcuffed to the man while the other was holding both umbrellas.[10]

They also make a brief cameo appearance in the Asterix book Asterix in Belgium.

They make an appearance in L'ombra che sfidò Sherlock Holmes, an Italian comic spin-off of Martin Mystère, edited by Sergio Bonelli Editore.[11][12]

The name of the pop group the Thompson Twins was based on Thomson and Thompson.

The detectives are regular characters in the 1991–1992 television series The Adventures of Tintin,[13] as well as the 2011 motion-capture film adaptation The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn. In the film, Simon Pegg and Nick Frost portray Thomson and Thompson.[14]

Names in other languages

In the original French, Dupond and Dupont are stereotypically prevalent surnames (akin to "Smith") and pronounced identically (IPA: [dypɔ̃]). The different letters indicate their different moustache styles: D for droit ("straight"), T for troussée ("turned up"). Translators of the series in some languages have tried to find names for the pair that are common, and similar or identical in pronunciation. They thus become:

- Uys and Buys in Afrikaans

- Tik and Tak (تيك and تاك) in Arabic

- Asín and Azín in Aragonese[15]

- জনসন (Johnson) and রনসন (Ronson) in Bengali

- Pichot and Pitxot in Cadaquesenc (Catalan dialect in Cadaques)

- Brea and Bray in Cornish

- Kadlec and Tkadlec in Czech

- Jansen and Janssen in Dutch

- Thomson and Thompson in English

- Citserono and Tsicerono in Esperanto

- Schulze and Schultze in German

- Schulz and Schulze in German (only in the 1990s TV Series)

- Santu and Bantu in Hindi[16]

- Clodius and Claudius in Latin

- Tajniak and Jawniak in Polish

- Hernández and Fernández in Spanish (Juventud edition only), Galician and Asturian

- Skapti and Skafti in Icelandic

- Tomson and Tompson in Serbian

- Zigue and Zague in older Portuguese editions

- Nisbet and Nesbit in Scots[17]

- An Dòmhnallach and MacDhòmhnaill in Scottish Gaelic

- Johns and Jones or Parry-Williams and Williams-Parry in Welsh (Dref Wen and Dalen editions, respectively)

- Roobroeck and Roobrouck in West Flemish (Kortrijk dialect)

- Aspeslagh and Haspeslagh in West Flemish (Ostend dialect)

In some languages, the French forms are more directly adapted, using local orthographic ambiguities:

- In Chinese

- Doo-bong and Doo-bong or Dù Bāng and Dù Bāng (杜邦 and 杜帮, or 杜邦 and 杜幫 in Traditional Chinese), or

- Du Bang and Du Pang (杜邦 and 杜庞)

- Ntypón and Ntipón in Greek (Ντυπόν and Ντιπόν, pronounced [diˈpon])

- Dyupon and Dyubon in Japanese (デュポン and デュボン)

- Dipons and Dipāns in Latvian

- Doupont and Douponṭ in Persian (دوپونت and دوپونط)

- Dwipong and Dwippong in Korean (뒤퐁 and 뒤뽕[18])

- Dyupon and Dyuponn in Russian (Дюпон and Дюпонн)

The original Dupond and Dupont are kept in Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, Hungarian, Turkish, Finnish, Indonesian, Italian, Basque, Catalan, the Casterman edition in Spanish, and the newer Portuguese editions.

See also

References

- ↑ Peeters 2012, p. 341, "Character Names in French and English".

- ↑ Apostolidès, Jean-Marie (2010). The Metamorphoses of Tintin, Or, Tintin for Adults. Stanford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-8047-6030-0.

When Thomson tacks on his famous "to be precise", most of the time he doesn't add anything but simply repeats what the other just said.

- ↑ "At the Grand Palais in Paris: Hergé, the Genius who Invented Tintin". Bonjour Paris. 22 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- 1 2 3 Assouline, Pierre (4 November 2009). Hergé: The Man Who Created Tintin. USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9780195397598. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ Apostolidès, Jean-Marie (2010). The Metamorphoses of Tintin, Or, Tintin for Adults. Stanford University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8047-6030-0. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

the two Yankee policemen who crash into each other while chasing Tintin (TA, 8, III, 2); and Mike MacAdam, the private detective who turns out to be a braggart, a coward and an incompetent (TA, pp. 45, 46, 58).

- ↑ "The Thomsons". tintin.com. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 52; Lofficier & Lofficier 2002, p. 31; Assouline 2009, p. 42; Peeters 2012, p. 65.

- ↑ Thompson 1991, p. 86.

- ↑ Farr 2001, p. 21.

- ↑ Michael Farr, Tintin: The Complete Companion, John Murray, 2001.

- ↑ L'ombra che sfidò Sherlock Holmes, Storie da Altrove, Sergio Bonelli Editore, November 2000, p. 55

- ↑ "L'Ombra che sfidò Sherlock Holmes". Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ "How could they do this to Tintin?". TheGuardian.com. 18 October 2011.

- ↑ Stephen Armstrong (21 September 2008). "Simon Pegg: He's Mr Popular". The Sunday Times. UK. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ↑ Tintín, el reportero más famoso del cómic, vive también sus aventuras en aragonés. Heraldo de Aragón. 4 April 2019

- ↑ "The Adventures of Tintin : Now in Hindi". Pratham Books. 25 May 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ↑ Characters & Places|The Derk Isle retrieved 9 September 2013

- ↑ ▒ 지성의 전당 도서출판 솔입니다 ▒ Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Farr, Michael (2001). Tintin: The Complete Companion. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5522-0.

- Lofficier, Jean-Marc; Lofficier, Randy (2002). The Pocket Essential Tintin. Harpenden, Hertfordshire: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-904048-17-6.

- Peeters, Benoît (2012) [2002]. Hergé: Son of Tintin. Tina A. Kover (translator). Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0454-7.

- Thompson, Harry (1991). Tintin: Hergé and his Creation. London: Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-52393-3.