Thomas Charles Scanlen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prime Minister of the Cape Colony | |

| In office 9 May 1881 – 12 May 1884 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Governor | Hercules Robinson |

| Preceded by | John Gordon Sprigg |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Upington |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 9 July 1834 Albany, Cape Colony |

| Died | 15 December 1912 (aged 78) Salisbury, BSAC Rhodesia |

| Nationality | British |

| Spouse(s) | Emma Thackwray, Sarah Ann Dennison |

| Occupation | Politician |

Sir Thomas Charles Scanlen KCMG (9 July 1834 – 15 December 1912) was a politician and administrator of the Cape Colony.

He was briefly Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, from 1881 to 1884, during an especially turbulent period in the Cape's history, dominated by conflicts such as the Basuto Gun War. He was also the Cape's first locally-born Prime Minister.

Early life

Scanlen was born 9 July 1834 on Longford Farm in the district of Albany in the Cape Colony. His family were of Irish ancestry, and had arrived in the eastern Cape among the 1820 Settlers. In 1845 his family moved from Grahamstown to Cradock, Cape Colony. Here he married Emma Thackwray on 1855, and the couple had several children.

Early political career

Scanlen's father Charles was elected as parliamentary representative for Cradock in 1856. Thomas succeeded his father as representative of Cradock in 1870, and was to serve in the Cape Parliament for a total of 26 years.

At the time he first entered parliament, the nation was split between the supporters of John Molteno's movement for "responsible government" (local democracy) and supporters of the British Imperial Governor Wodehouse. Scanlen's first move was to declare official neutrality in this conflict, claiming that he was as yet far too ignorant of the issues. He eventually gave his cautious support to the responsible government movement, which triumphed in 1872. He turned down the new Prime Minister's unofficial offer of a government position, but gave the Molteno government his support for its various infrastructure and development projects. When the Molteno government was overthrown by an imperial intervention, Scanlen moved into opposition against the new aggressively pro-imperialist government of Gordon Sprigg, dubbed "The Settler Ministry", as it was composed entirely of 1820 settlers from Sprigg's own frontier region of the Cape.[1]

The Scanlen Ministry (1881-1884)

The Scanlen government acquired the nickname "The Humdrum Ministry", as it was primarily concerned with damage-control and restoring normality to the country, after the disastrous Sprigg government. It was also dominated by the concern to undo the extravagant military expansions of the Sprigg government, by shedding the conquered territories in Basutoland and the Transkei, and by the need to appease the newly inflamed tension between British and Boer citizens of the Cape.

Background

In 1881, the unpopular and unelected government of Prime Minister John Gordon Sprigg fell, amidst the widespread unrest and frontier wars resulting from the British Colonial Office's disastrous attempt to enforce a confederation system on southern Africa. The British Governor Henry Bartle Frere had just been recalled to London in 1880 to face charges of misconduct and, deprived of its principle backer, the Sprigg ministry collapsed. In the political vacuum, the Cape's first Prime Minister John Molteno was invited to come out of retirement to take over government, however he declined, and instead suggested Scanlen as a sufficiently qualified leader to form a government. Saul Solomon, John X. Merriman and Jan Hendrik Hofmeyr (Onze Jan) were also offered the position, but it was to Scanlen that the invitation was given in the end.[2][3]

In the charged atmosphere of the time, powerful political factions were squaring off, however none could command an absolute majority alone. Scanlen was therefore quickly accepted as a "safe" compromise candidate who was politically neutral and could be accepted by all. He was also prudent and astute by nature, and in the context of the ruinous military and economic situation, all factions accepted the need for a technocrat government.

Consequently, on 9 May 1881, Thomas Scanlen was appointed as the 3rd Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, and the first locally-born person to hold this position.

Specific challenges

At its accession, Scanlen's new government confronted two full-blown wars and a string of smaller conflicts, all caused by Frere's recently failed confederation scheme. Nearby, the first Anglo-Boer war had just seen the British lose control of the Transvaal, while the Anglo-Zulu war had seen disasters such as Isandlwana.

Public debt

Serious financial problems also faced the Scanlen government from its onset, and at the time this issue dwarfed all others in urgency and importance. The massive confederation wars had sapped the Colony's resources, accruing a debt of over 16 million (mostly from military spending) and seeing the Cape's exports peter off. In addition, the subsequent withdrawal of the Imperial garrisons reduced local demand for goods and infrastructure.[4]

In spite of these challenges, Scanlen's government began gradually to make headway. He led a movement to return to the highly successful and locally oriented development policies of the Cape's first ministry. For this purpose, he re-appointed John X. Merriman as his Commissioner of Public Works, and Molteno himself briefly came out of retirement to assist Scanlen in forming his cabinet and to advise him as Colonial Secretary.

The country's economy slowly began to revive and the diamond industry started to recover. Although the effects were only gradually felt in the years to come, economic recovery had begun.[5]

Basuto Gun War

The Cape itself was still heavily involved in the Basuto Gun War, an expensive and ongoing legacy of Prime Minister Sprigg's policies. Scanlen's government sent envoys such as JW Sauer and General CG Gordon to the Basuto leaders, and made several attempts to renounce its authority from Basutoland entirely. The war began to die down after Scanlen's government negotiated a peace treaty in 1881, and succeeded in peacefully withdrawing all authority over the territory. After Scanlen's government dis-annexed it, the British assumed responsibility for Basutoland and took it over as a protectorate. Basutoland was never more to be a part of the Cape Colony and, because of this move, in years to come, it was eventually to become the independent state of Lesotho, separate from the rest of South Africa.[6]

Another legacy issue was the German invasion of neighbouring South West Africa.

Transkei disannexation

Similar to Basutoland, Scanlen's government wished to dis-annex the Transkei (another costly and turbulent territory which Sprigg had conquered). However Scanlen faced the problem of British opposition to this move. The British government has permitted him to withdraw from Basutoland, but saw itself having to take responsibility for the Transkei too. The powerful Afrikaner Bond party also opposed disannexation of Transkei and Tembuland, and the move was blocked.

Stellaland and Goshen

Boer settlers and mercenaries from the Transvaal had recently invaded neighbouring Bechuanaland and established settlements that later became the miniature Boer republics of Stellaland and Goshen.

Scanlen's government wished to protect the Bechuana people's independence and evict the Boer settlers from the Tswana lands. However he once again was opposed by the powerful Afrikaner Bond party, which saw Bechuanaland as being in the Boer sphere of influence, and Scanlen's moves were blocked.

Caught between his liberal cabinet members, and the conservative Afrikaner Bond party, Scanlen travelled alone to London (Oct 1883 - Jan 1884) to negotiate with the British and Transvaal governments. In his absence, the Bond lobbies against him using its press outlets such as De Zuid-Afrikaan and branding Scanlen a British imperialist. Scanlen's parliamentary support also fell to a new low.

Rise of Afrikaner nationalism

By the time of Scanlen's ministry, the earlier grievances between the eastern and western halves of the Cape Colony had mostly been laid to rest. However, Frere's failed Confederation scheme and the First Boer War had led to these tensions merely being replaced by friction between the English and Afrikaans speaking populations of the Cape.

The newly founded Afrikaner Bond had held its first congress in 1882 at Graaf Reinet, and went on to secure a significant degree of parliamentary control. Scanlen's was the first Cape government to be forced into uneasy cooperation with this powerful new group, and all of his government's issues were coloured by the need to deal with the Bond. In addition, signs of the increasing cultural assertiveness of the Cape Afrikaners swiftly followed during Scanlen's tenure, included the first introduction of the Dutch language into the House of Assembly.

Scanlen had come under intense pressure from the Afrikaner Bond on the issues of de-annexing Basutoland and Transkei (which the Bond saw as land that should be opened for white settlement). This pressure reached a new level when Scanlen opposed the Stellaland & Goshen Boer settlers in Bechuanaland.

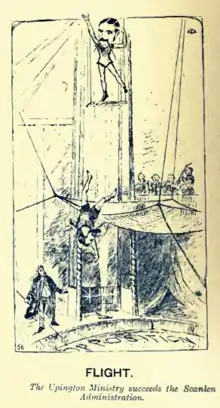

Without the support of the Bond, Scanlen could barely command an effective majority in parliament. Scanlen was compelled to resign in May 1884. He was replaced as Premier by Thomas Upington - a political ally of the Bond.[7] He was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) in the 1884 Birthday Honours.[8]

Later life

In describing him, the Dictionary of National Biography states:

Scanlen was not an outstanding politician. He had a good legal brain, was a conscientious worker and a good back bencher, but he was neither a good orator nor a leader. It was his misfortune that, in assuming the Premiership, he also inherited Sprigg's legacy of intractable problems. In private life, Scanlen was modest and retiring. He was a difficult conversationalist, having virtually no small talk, but he possessed a dry sense of humour and was a shrewd judge of character.[9]

Scanlen continued to serve as leader of the parliamentary opposition until 1889 but his personal life suffered. He underwent considerable financial losses due to a series of bad investments. His first wife had died in 1856. The couple had only had two surviving children: a libertine, Charles (whom Scanlen dubbed "the prodigal Charlie") and an invalid, Kate). In 1888 his second wife, his cousin Sarah Ann Dennison, left him and moved to England with their child. Of the ten children he fathered in both his marriages, only four survived to adulthood.

In 1895, he moved to Salisbury, Rhodesia (now Harare, Zimbabwe) where he started a legal practice. He went on to become legal adviser to Cecil Rhodes's Chartered Company, for which he acted as Administrator on several occasions, and acting Public Prosecutor. In 1896 he became senior member of the Rhodesian Executive Council, and in 1899 he became a member of the Rhodesian Legislative Council (of which he became the Chairman in 1902).[10][11]

Scanlen retired on pension in 1908 and died on 15 December 1912 in Salisbury, Rhodesia.

References

- ↑ Basil T. Hone: The First Son of South Africa to be Premier: Thomas Charles Scanlen. Oldwick, New Jersey: Longford Press, 1993. p.50.

- ↑ G.M. Theal: History of South Africa, from 1873 to 1884. Twelve eventful years. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. Vol.II, p.70.

- ↑ P. A. Molteno: The life and times of Sir John Charles Molteno, Comprising a History of Representative Institutions and Responsible Government at the Cape. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1900

- ↑ Beck, Roger B. (1 March 1996). "Cape Politics The First Son of South Africa to be Premier: Thomas Charles Scanlen". The Journal of African History. 37 (1): 143–144. doi:10.1017/S0021853700034964. S2CID 154786465. Retrieved 3 September 2016 – via Cambridge Journals Online.

- ↑ Basil T. Hone: The First Son of South Africa to be Premier: Thomas Charles Scanlen. Oldwick, New Jersey: Longford Press, 1993. ISBN 0-9635572-5-4

- ↑ "Gun_War". Archived from the original on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ "History of Cape Colony from 1870 to 1899". Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ "No. 25357". The London Gazette. 23 May 1884. p. 2286.

- ↑ D. W. Kruger: Dictionary of South African Biography. Vol II. Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria. Tafelberg Ltd, 1972. ISBN 0-624-00369-8. p.626

- ↑ "Our History". www.scanlenandholderness.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011.

- ↑ "RootsWeb: SOUTH-AFRICA-L Re: [ZA] Scanlens". Retrieved 3 September 2016.

Further reading

- Basil T. Hone: The First Son of South Africa to be Premier: Thomas Charles Scanlen. Oldwick, New Jersey: Longford Press, 1993. ISBN 0-9635572-5-4

- R. Kent Rasmussen:Dictionary of African historical biography. University of California Press, 1989. ISBN 0-520-06611-1

- Dictionary of National Biography

.svg.png.webp)