E isomer | |

Z isomer | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

{3-[(2-Chloro-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)methyl]-5-methyl-1,3,5-oxadiazinan-4-ylidene}nitramide | |

| Other names

CGA293343 | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 8555232 | |

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.102.703 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII |

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties[1] | |

| C8H10ClN5O3S | |

| Molar mass | 291.71 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.57 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 139.1 °C (282.4 °F; 412.2 K) |

| 4.1 g/L | |

| log P | -0.13 |

| Hazards[2] | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H302, H410 | |

| P264, P270, P273, P301+P312, P330, P391, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Thiamethoxam is the ISO common name[3] for a mixture of cis-trans isomers used as a systemic insecticide of the neonicotinoid class. It has a broad spectrum of activity against many types of insects and can be used as a seed dressing.

A 2018 review by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that most uses of neonicotinoid pesticides such as Thiamethoxam represent a risk to wild bees and honeybees.[4][5] In 2022 the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) concluded that Thiamethoxam is likely to adversely affect 77 percent of federally listed endangered or threatened species and 81 percent of critical habitats.[6] The pesticide has been banned for all outdoor use in the entire European Union since 2018, but has a partial approval in the U.S. and other parts of the world, where it is widely used.[7][8]

History

Thiamethoxam was developed by Ciba-Geigy (now Syngenta) in 1991[9] and launched in 1998;[10] a patent dispute arose with Bayer which already had patents covering other neonicotinoids including imidacloprid and clothianidin. In 2002 the dispute was settled, with Syngenta paying Bayer $120 million in exchange for worldwide rights to thiamethoxam.[11]

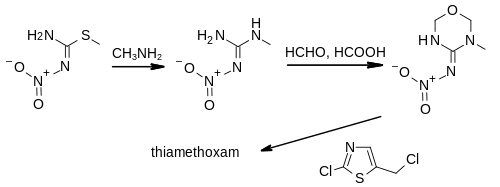

Synthesis

Thiamethoxam was first prepared by chemists at Ciba Geigy in 1991. S-Methyl-N-nitro-isothiourea is treated with methylamine to give N-methyl nitroguanidine. This intermediate is used in a Mannich reaction with formaldehyde in formic acid to give 3-methyl-4-nitroimino-1,3,5-oxadiazinane. In the final step, the heterocycle is N-alkylated with a thiazole derivative to give a mixture of E and Z isomers of the final product.[12]

Mechanisms of action

Thiamethoxam is a broad-spectrum, systemic insecticide, which means it is absorbed quickly by plants and transported to all of its parts, including pollen, where it acts to deter insect feeding. An insect can absorb it in its stomach after feeding, or through direct contact, including through its tracheal system. The compound gets in the way of information transfer between nerve cells by interfering with nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the central nervous system, and eventually paralyzes the muscles of the insects.[13]: 17

Syngenta asserts that thiamethoxam improves plant vigor by triggering physiological reactions within the plant, which induce the expression of specific "functional proteins" involved in various stress defense mechanisms of the plant allowing it to better cope under tough growing conditions, such as "drought and heat stress leading to protein degradation, low pH, high soil salinity, free radicals from UV radiation, toxic levels of aluminum, wounding from pests, wind, hail, etc, virus attack".[14]: 16

Toxicity

The selective toxicity of neonicotinoids like thiamethoxam for insects versus mammals is due to the higher sensitivity of insects' acetylcholine receptors.[15] The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the U.N. assessed thiamethoxam as "moderately hazardous to humans (WHO class III)", because it is harmful if swallowed. It found it to be no skin or eye irritant, and not mutagenic in any in vitro and in vivo toxicology tests.[13]: 20

FAO described thiamethoxam as non-toxic to fish, daphnia and algae, mildly toxic for birds, highly toxic to midges and acutely toxic for bees.[13]: 20 The Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) classification is: "Harmful if swallowed. Very toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects".[13]: 20 Thiamethoxam at sublethal concentrations can increase aggressiveness and cannibalism in commercially harvested shrimp such as Procambarus clarkii[16] In bioassays pf aquatic organisms, fish, aquatic primary producers, mollusks, worms, and rotifers are often largely insensitive to thiamethoxam concentrations found in surface waters, but insects, such as chironomid larva are especially susceptible.[17][18]

Sublethal doses of thiamethoxam metabolite clothianidin (0.05–2 ng/bee) have been known to cause reduced foraging activity since at least 1999, but this was quantified in 2012 by RFID tagged honeybees.[19] Doses of equal or more than 0.5 ng/bee caused longer foraging flights.[19]

Regulation and use

United States

Thiamethoxam has been approved for use in the US as an antimicrobial pesticide, wood preservative and as a insecticide; it was first approved in 1999.[20]: 4 & 14 It is still approved for use in a wide range of crops.[21][22]

On September 5, 2014 Syngenta petitioned the EPA to increase the legal tolerance for thiamethoxam residue in numerous crops.[23] It wanted to use thiamethoxam as a leaf spray, rather than just a seed treatment, to treat late to midseason insect pests.[24]

The estimated annual use of the compound in US agriculture is mapped by the US Geological Service and showed an increasing trend from its introduction in 2001 to 2014 when it reached 1,420,000 pounds (640,000 kg).[25] However, use from 2015 to 2019 dropped sharply following concerns about the effect of neonicotinoid chemicals on pollinating insects.[26] In May 2019, the Environmental Protection Agency revoked approval for a number of products containing thiamethoxam as part of a legal settlement.[27] However, certain formulations continue to be available.[22]

Neonicotinoids banned by the European Union

In 2012, several peer reviewed independent studies were published showing that several neonicotinoids had previously undetected routes of exposure affecting bees including through dust, pollen, and nectar; that sub-nanogram toxicity resulted in failure to return to the hive without immediate lethality, the primary symptom of colony collapse disorder; and showing environmental persistence in agricultural irrigation channels and soil. However, not all earlier studies carried out before 2014 have found significant effects.[28] These reports prompted a formal peer review by the European Food Safety Authority, which stated in January 2013 that neonicotinoids pose an unacceptably high risk to bees, and that the industry-sponsored science upon which regulatory agencies' claims of safety have relied on may be flawed and contain several data gaps not previously considered.[29] In April 2013, the European Union voted for a two-year restriction on neonicotinoid insecticides. The ban restricts the use of imidacloprid, clothianidin, and thiamethoxam on crops that attract bees.[30]

In February 2018, the European Food Safety Authority published a new report indicating that neonicotinoids pose a serious danger to both honey bees and wild bees.[31] In April 2018, the member states of the European Union decided to ban the three main neonicotinoids (clothianidin, imidacloprid and thiamethoxam) for all outdoor uses.[32]

Other countries

Thiamethoxam is approved for a wide range of agricultural, viticultural(vineyard), and horticultural uses.[13]: 17

Emergency use

In January 2021 the UK allowed this pesticide to be used to save sugar beet plants in danger of damage from beet yellows virus which is transmitted by aphids.[33] However due to lower levels of this disease than was expected, it was announced in March 2021 that the conditions for emergency use had not been met.

References

- ↑ Pesticide Properties Database. "Thiamethoxam". University of Hertfordshire. Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- ↑ PubChem Database (2022-01-15). "N-[3-[(2-chloro-1,3-thiazol-5-yl)methyl]-5-methyl-1,3,5-oxadiazinan-4-ylidene]nitramide". Retrieved 2022-01-22.

- ↑ "Compendium of Pesticide Common Names". BCPC.

- ↑ "Neonicotinoids: risks to bees confirmed | EFSA". www.efsa.europa.eu. 2018-02-28. Retrieved 2023-06-23.

- ↑ "Conclusion on the peer review of the pesticide risk assessment for bees for the active substance clothianidin". EFSA Journal. 11: 3066. 2013. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2013.3066.

- ↑ US EPA, OCSPP (2022-06-16). "EPA Finalizes Biological Evaluations Assessing Potential Effects of Three Neonicotinoid Pesticides on Endangered Species". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 2023-06-23.

- ↑ Carrington, Damian (2018-04-27). "EU agrees total ban on bee-harming pesticides". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-06-23.

- ↑ Milman, Oliver (2022-03-08). "Fears for bees as US set to extend use of toxic pesticides that paralyse insects". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-06-23.

- ↑ Peter Maienfisch; Max Angst; Franz Brandl; et al. (October 2001). "Chemistry and biology of thiamethoxam: a second generation neonicotinoid". Pest Management Science. 57 (10): 906–913. doi:10.1002/ps.365. PMID 11695183.

- ↑ Peter Maienfisch; Hanspeter Huerlimann; Alfred Rindlisbacher; et al. (February 2001). "The discovery of thiamethoxam: a second-generation neonicotinoid". Pest Management Science. 57 (2): 165–176. doi:10.1002/1526-4998(200102)57:2<165::AID-PS289>3.0.CO;2-G. PMID 11455647.

- ↑ West, Bob (13 February 2002). "Syngenta Settles Patent Dispute with Bayer". lawnandlandscape.com. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ↑ Maienfisch, Peter (2006). "Synthesis and Properties of Thiamethoxam and Related Compounds". Zeitschrift für Naturforschung B. 61 (4): 353–359. doi:10.1515/znb-2006-0401. S2CID 8031781.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "FAO Specifications and Evaluations for Agricultural Pesticides: Thiamethoxam" (PDF). 21 June 2000.

- ↑ Syngenta (2006). "Thiamethoxam Vigor Effect" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ↑ Patrick H Rose (2012). "6.3.2.Selective Toxicity of Nicotine and Neonicotinoids". In Marrs, Timothy C. (ed.). Mammalian Toxicology of Insecticides. The Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 186. ISBN 978-1849731911.

- ↑ Butcherine, Peter; Benkendorff, Kirsten; Kelaher, Brendan; Barkla, Bronwyn J. (February 2019). "The risk of neonicotinoid exposure to shrimp aquaculture". Chemosphere. 217: 329–348. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.10.197.

- ↑ Zhang, Xidong; Huang, Yaohua; Chen, Wen-Juan; Wu, Siyi; Lei, Qiqi; Zhou, Zhe; Zhang, Wenping; Mishra, Sandhya; Bhatt, Pankaj; Chen, Shaohua (February 2023). "Environmental occurrence, toxicity concerns, and biodegradation of neonicotinoid insecticides". Environmental Research. 218: 114953. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2022.114953.

- ↑ Finnegan, Meaghean C.; Baxter, Leilan R.; Maul, Jonathan D.; Hanson, Mark L.; Hoekstra, Paul F. (October 2017). "Comprehensive characterization of the acute and chronic toxicity of the neonicotinoid insecticide thiamethoxam to a suite of aquatic primary producers, invertebrates, and fish: Thiamethoxam acute and chronic aquatic toxicity". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 36 (10): 2838–2848. doi:10.1002/etc.3846.

- 1 2 Christof W. Schneider; Jürgen Tautz; Bernd Grünewald; Stefan Fuchs (11 January 2012). "RFID Tracking of Sublethal Effects of Two Neonicotinoid Insecticides on the Foraging Behavior of Apis mellifera". PLOS ONE. 7 (1): e30023. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...730023S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030023. PMC 3256199. PMID 22253863.

- ↑ EPA Dec 21, 2011 Thiamethoxam Summary Document Registration Review Initial Docket Entire docket is available here

- ↑ §180.565 Thiamethoxam; tolerances for residues.

- 1 2 Syngenta. "Actara Insecticide". Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ↑ Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (5 September 2014). "Receipt of Several Pesticide Petitions Filed for Residues of Pesticide Chemicals in or on Various Commodities" (PDF). Federal Register. 79 (172): 53009–530013. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ↑ Britt E. Erickson (15 September 2014). "Syngenta Stands Firm On Neonicotinoids". Chemical & Engineering News. American Chemical Society. 92 (37): 7. doi:10.1021/cen-09237-notw1. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- 1 2 US Geological Survey (2021-10-12). "Estimated Annual Agricultural Pesticide Use for thiamethoxam, 2019". Retrieved 2022-01-24.

- ↑ "EPA Actions to Protect Pollinators". US EPA. 3 September 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ↑ Allington A (21 May 2019). "EPA Curbs Use of 12 Bee-Harming Pesticides". Bloomberg. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ↑ "Scientific opinions differ on bee pesticide ban". BBC News. 29 April 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ EFSA (2012). "Assessment of the scientific information from the Italian project 'APENET' investigating effects on honeybees of coated maize seeds with some neonicotinoids and fipronil". EFSA Journal. 10 (6): 2792. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2792.

- ↑ "Bees & Pesticides: Commission goes ahead with plan to better protect bees". Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ↑ Damian Carrington, "Total ban on bee-harming pesticides likely after major new EU analysis", The Guardian, 28 February 2018 (page visited on 29 April 2018).

- ↑ Damian Carrington, "EU agrees total ban on bee-harming pesticides ", The Guardian, 27 April 2018 (page visited on 29 April 2018).

- ↑ "BBC News - UK allows emergency use of bee-harming pesticide". BBC News. 3 March 2021.