A 3D reconstruction of the Theatre of Pompey | |

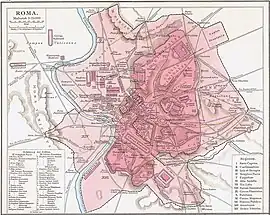

Theatre of Pompey Shown within Augustan Rome | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Location | Regio IX Circus Flaminius |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′43″N 12°28′25″E / 41.89528°N 12.47361°E |

| Type | Roman theatre |

| History | |

| Builder | Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus |

| Founded | 62 – 55 or 52 BC |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Rome and the fall of the Republic |

|---|

|

People

Events

Places |

The Theatre (UK) or Theater (US) of Pompey (Latin: Theatrum Pompeii, Italian: Teatro di Pompeo), also known by other names, was a structure in Ancient Rome built during the latter part of the Roman Republican era by Pompey the Great. Completed in 55 BC, it was the first permanent theatre to be built in Rome. Its ruins are located at Largo di Torre Argentina.

Enclosed by the large columned porticos was an expansive garden complex of fountains and statues. Along the stretch of the covered arcade were rooms dedicated to the exposition of art and other works collected by Pompey during his campaigns. On the opposite end of the garden complex was the Curia of Pompey for political meetings. The senate would often use this building along with a number of temples and halls that satisfied the requirements for their formal meetings. The curia is infamous as the place where Julius Caesar was assassinated by Brutus and Cassius during a session of the Senate on 15 March 44 BC.

Names

The Theatre of Pompey had a number of names in Latin. Theatrum Pompeii was most common, but it was also called the Pompeian Theater (Theatrum Pompeianum),[1] the Marble Theatre (Theatrum Marmoreum),[2] and simply the Theatre (Theatrum),[3] as it was "always the most important theatre in Rome".[4]

History

Origin

Pompey paid for this theatre to gain political popularity during his second consulship. According to Plutarch, Pompey was inspired by his visit in 62 BC to a Greek theatre in Mytilene.[5] However, this is likely mistaken, as the theatre at Mytilene would have been built into a hill-side and, unlike Pompey's theatre, did not have a scaena. If any inspiration came from the theatre there, it must have been largely reworked or discarded, as Rome's urban geography made such a project unadaptable.[4] Construction began around 61 BC.[6]

Prior to its construction, permanent stone theatres had been forbidden, and so to side-step this issue, Pompey had the structure built in the Campus Martius, outside of the pomerium, or sacred boundary, that divided the city from the ager Romanus (the territory immediately outside the city).[7][8] Pompey also had a temple to Venus Victrix built near the top of the theatre's seating; Pompey then claimed that he had "not [built] a theatre, but rather a temple of Venus to which I have added the steps of a theatre".[9] This was done, according to Tertullian, to avoid censure but the claim was likely in jest.[10]

The sources on the dedication are contradictory. Pliny reports its dedication in 55 BC, the year of Pompey's second consulship. However, Gellius preserves a letter by Cicero's freedman, Tiro that dates the dedication to Pompey's third consulship in 52 BC; in the letter, Pompey requests clarification as to whether to inscribe consul tertio or consul tertium.[11][12] It may be, however, that different portions of the theatre – the theatre proper, the scaena, and the adjoining temple – were completed at different times.[13]

Two performances are associated with the dedication: Clytemnestra by Accius, and Equos Troianus either by Livius Andronicus or Gnaeus Naevius.[14] Clodius Aesopus, a renowned tragic actor, was brought out of retirement in order to act in the theatre's opening show. The show was also accompanied by gladiatorial matches featuring exotic animals.[8] The showing of Clytemnestra proved an opportunity for Pompey to restage his triple triumph from 61 BC, representing himself both as Alexander the Great and as Agamemnon.[15] Other events were also held around the city in the celebrations, including musical and gymnastic contests along with horse races.[16]

Post-Pompey and the Roman Empire

Following Pompey's defeat and subsequent assassination in 48 BC during the Great Roman Civil War (49–45 BC), Caesar used the theatre to celebrate the triumph over Pompey's forces in Africa. The theatre itself was the site of Caesar's assassination. At the time, the Roman Senate had been using various venues to conduct business, as the Senate House itself was under renovation.

For forty years, the theatre was the only permanent theatre located in Rome, until Lucius Cornelius Balbus the Younger constructed the Theatre of Balbus in 13 BC in the campus Martius. Regardless, the Theatre of Pompey continued to be the main location for plays, both due to its splendour and its size. In fact, the site was often considered the premiere theatre throughout its entire life. Seeking association with the great theatre, others constructed their own in and around the area of Pompey's. This led to the eventual establishment of a theatre district, in the most literal sense.[8]

Octavian, in 32 BC, renovated the theatre and moved the statute of Pompey at which Caesar was murdered from the curia to the scaena.[17] The theatre burned in AD 21 and afterwards, Tiberius reconstructed the portions destroyed.[18] During the reconstructions, a statue of Sejanus was set up in the theatre on decree of the senate but it did not survive Sejanus' downfall.[19] The Tiberian restorations were completed under Caligula but dedicated by Claudius.[20] During Claudius' restorations, his name – along with that of Tiberius – were inscribed next to that of Pompey.[21]

The porticos and theatre were maintained for centuries. Octavian restored parts of the complex in 32 BC, and in AD 21 Tiberius initiated a reconstruction of the part of the theatre that had been destroyed by fire which was completed during the reign of Caligula. Claudius rededicated the Temple of Venus Victrix; Nero gilded the interior of the temple for the visit of Tiridates in AD 66.[22] The scaena burned in a large fire in AD 80 and was restored by Domitian. There were further restorations under Septimius Severus; one Quinus Acilius Fuscus is noted by inscription as procurator operis Theatri Pompeiani.[23] The fire burned again in AD 247 and was later restored under the emperors Diocletian and Maximian, emperors Honorius and Arcadius,[24] and later by Symmachus.[25]

A catalogue compiled at the end of the 4th century recorded that the theatre's seating capacity was 22,888 persons.[26] A modern estimate of capacity, in the 1992 A new topographical dictionary of ancient Rome, places its capacity at 11,000.[25] After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in AD 476, the Theatre of Pompey remained in use and when the city of Rome came under the dominion of the Ostrogothic Kingdom, the structure was once again renovated between AD 507–511.[27] However, this renovation would be its last. Following the destructive Gothic War (535–554) there was no need for a large theatre because the population of Rome had declined drastically. As such, the theatre was allowed to deteriorate.[28]

From the Middle Ages to the present

During the Early Middle Ages, the marble covering of the theatre was used as a material to maintain other buildings. Being located near the Tiber, the building was also regularly flooded which caused further damage.[28] Nevertheless, the concrete core of the building remained standing in the 9th century AD, as a pilgrim guidebook from that time still listed the site as a theatrum.[28][29] By the 12th century, buildings had started to encroach upon the remains; two churches, Santa Barbara and Santa Maria in Grotta Pinta were constructed on the site, with the latter probably having been built over one of the theatre's access corridors.[29] However, the floor plan of the old theatre was still recognizable.[28] In 1140, one source referred to the ruins as the Theatrum Pompeium, whereas another referred to it as the "temple of Cneus pompeii". In 1150, Johannes de Ceca is reputed to have sold a trillium, or round structure (i.e. the theatre curve) to an ancestor of the Orsini family. In 1296, the site of the theatre was turned into a fortress by the Orsini.[29] Later in the Middle Ages, the square of Campo de' Fiori was built and the remaining parts of the theatre were quarried to supply stone for many newer buildings which still exist in modern Rome.[28]

Today, not much remains visible of the once majestic theatre, as the vestiges of the structure have entirely been enveloped by the structures that lie between the Campo de' Fiori and Largo di Torre Argentina. The largest intact sections of the theatre are found in the Palazzo della Cancelleria, which used much of the bone-coloured travertine for its exterior from the theatre. The large red and grey columns used in its courtyard are from the porticoes of the theatre's upper covered seating; however, they were originally taken from the theatre to build the old Basilica of S. Lorenzo.[30] And while the theatre itself is no longer discernible, the imprint of the building itself can still be detected; the structure’s semicircular form can today be traced by walking east from the Campo de' Fiori through the Palazzo Orsini Pio Righetti. The path of the Via di Grotta Pinta, near the Via dei Chiavari, also roughly follows the outline of the theatre's original stage. Deep within the recesses of basements and wine cellars of buildings located in the Campo de' Fiori, arches and fragments of the theatre's walls and foundations can still be seen.[31] The ground plan of the Palazzo Pio also reveals that many of the supporting spokes of the theatre were re-purposed into walls for new rooms.[32] The arches that were left after the theatre’s abandonment even led to the name of the aforementioned Santa Maria di Grotta Pinta (i.e. the "painted grotto").[33]

Excavation and study

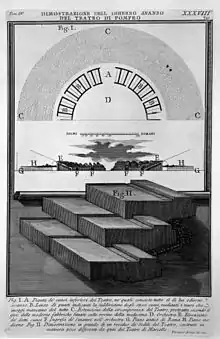

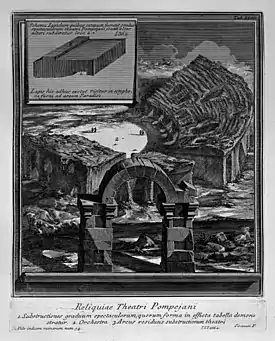

One of the first individuals to draw the ruins of the theatre was Giovanni Battista Piranesi, who made two notable etchings depicting the theatre in the middle of the 18th century. The first, entitled "A Demonstration of the Current Remains of the Theatre of Pompey" (Dimonstrazione del Odierno Avanzo del Teatro di Pompeo), illustrates, from both a top-down and a cross-section perspective, a view of the ruins. This illustration suggests that the only remnants of the once-great structure in the 18th century were portions of the seating closest to the orchestra, or the ima cavea. Piranesi specifically notes that four of the large doors (vomitoria) through which spectators would have entered the complex were still preserved. However, much of the height of the building had long ago been stripped away.[34]

Another etching, entitled "The Remains of the Theatre of Pompey", shows a more artistic view of the structure. This illustration, facing the south-east, postulates that the remaining ima cavea was split on the Western side, where the ancient stairs to the Temple of Venus would have been located. The image also prominently shows a remaining substructure arch that originally would have supported the media and summa caveae.[35] Piranesi seems to have been basing his drawings largely on what he could imagine, as in the legend for "A Demonstration of the Current Remains of the Theatre of Pompey", he explicitly mentions that these etchings illustrate what the theatre would look like if modern structures were removed from the site (protratta secondo il giro delle moderne fabbriche situate sullo rovine della medesima).[34][35]

Luigi Canina (1795–1856) was the first to undertake serious research on the theatre. Canina examined what ruins he could and then combined this information with Vitruvius' famous description of a Roman theatre, thereby producing a working plan of the theatre. Later in 1837, Victoire Baltard used Canina's work, as well as information gleaned from the Forma Urbis to construct a more refined plan.[36] Much like Piranesi before him, Baltard also created a sketch of what the ruins would look like were they to be completely excavated.[37]

Description

The structure and connecting quadriporticus had multiple uses. The building had the largest crypta of all the Roman theatres. This area, located behind the stage and within an enclosure, was used by patrons between acts or productions to stroll, purchase refreshments or just to escape to the covered porticoes from the sun or rain.[38]

The Porticus Pompeii contained statues of great artists and actors. Long arcades exhibiting collections of paintings and sculpture as well as a large space suitable for holding public gatherings and meetings made the facility an attraction to Romans for many reasons. Lavish fountains were fed by water purchased from a nearby aqueduct and stored. It is not known if the water supply would have been enough to run the waterworks for more than a few hours a day, or if some other supply allowed the fountains to run nearly nonstop.[30]

The remains of the east side of the quadriporticus, and three of four temples from an earlier period often associated with the theatre can be seen on the Largo di Torre Argentina.[39] The fourth temple remains largely covered by the modern streets of Rome. This archaeological site was excavated by order of Mussolini in the 1920s and 1930s.[40] The scarce remains of the theatre itself can be found off the Via di Grotta Pinta underground.[41] Vaults from the original theatre can be found in the cellar rooms of restaurants off this street, as well as in the walls of the hotel Albergo Sole al Biscione.[42] The foundations of the theatre as well as part of the first level and cavea remain, but are obscured, having been overbuilt and extended. Over building throughout the centuries has resulted in the surviving ruins of the theatre's main structure becoming incorporated within modern structures.[30]

Architecture

The characteristics of Roman theatres are similar to those of the earlier Greek theatres on which they are based. However, Roman theatres have specific differences, such as being built upon their own foundations instead of earthen works or a hillside and being completely enclosed on all sides.[43]

Rome had no permanent theatres within the city walls until this one. Theatres and amphitheatres were temporary wooden structures that could be assembled and disassembled quickly. Attempts to build permanent stone structures were always halted by political figures or simply did not come to full fruition.[44]

Pompey was supposedly inspired to build his theatre from a visit to the Greek theatre of Mytilene on Lesbos.[45] The structure may have been a counterpart to the Roman Forum. The completion of this structure may also have prompted the building of the Imperial Fora.[45][46] Julius Caesar would come to copy Pompey's use of the spoils of war to illustrate and glorify his own triumphs when building his forum which in turn would be copied by emperors.[46] The use of public space incorporating temple architecture for personal political ambition was taken from Sulla and those prior to the dictator. Using religious associations and ritual for personal glorification and political propaganda were an attempt to project a public image.[46]

The use of concrete and stone foundations allowed for a free standing Roman theatre and amphitheatre.[47]

The stage and scaenae frons sections of the theatre is attached directly to the auditorium, making both a single structure enclosed all around, whereas Greek theatres separate the two.[48] The cavea – the seating area – had a diameter of around 150–160 metres; the scaena measured approximately 95 metres.[25] This created acoustic issues requiring different techniques to overcome.[49]

This architecture was the model for nearly all future theatres of Rome and throughout the empire. Notable structures that used a similar style are the Theatre of Marcellus and the Theatre of Balbus, both of which can be seen on the marble plan of the city.[50]

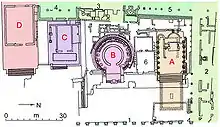

Associated temple complex

In order to build the theatre as a permanent stone structure, a number of things were done, including building outside the city walls. By dedicating the theatre to Venus Victrix and building the temple central within the cavea, Pompey made the structure a large shrine to his personal deity. He also incorporated four Republican temples from an earlier period in a section called the "Sacred Area" in what is today known as Largo di Torre Argentina. The entire complex is built directly off the older section which directs the structure's layout. In this manner, the structure had a day-to-day religious context and incorporates an older series of temples into the newer structure.

Temple A was built in the 3rd century BC, and is probably the Temple of Juturna built by Gaius Lutatius Catulus after his victory against the Carthaginians in 241 BC.[51] It was later rebuilt into a church; its apse is still present.

Temple B, a circular temple with six columns remaining, was built by Quintus Lutatius Catulus in 101 BC to celebrate his victory over Cimbri; it was Aedes Fortunae Huiusce Diei, a temple devoted to the "Luck of the Current Day". The colossal statue found during excavations and now kept in the Capitoline Museums was the statue of the goddess herself. Only the head, the arms, and the legs were of marble: the other parts, covered by the dress, were of bronze.

Temple C is the most ancient of the four, dating back to the 4th or 3rd century BC, and was probably devoted to Feronia, the ancient Italic goddess of fertility. After the fire of 80 AD, this temple was restored, and the white and black mosaic of the inner temple cell dates back to this restoration.

Temple D is the largest of the four; it dates back to the 2nd century BC with Late Republican restorations, and was devoted to Lares Permarini, but only a small part of it has been excavated (a street covers the most of it).

See also

References

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 384, citing Plin. NH 36.115; Suet. Tib. 47.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 384, citing Fast. Amit. 12 August.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 384, citing Suet. Ner. 13.2.

- 1 2 Richardson 1992, p. 384.

- ↑ Plut. Pomp., 42.4.

- ↑ Kuritz 1987, p. 48.

- ↑ Boëthius 1978, p. 206.

- 1 2 3 Erasmo 2010, p. 83.

- ↑ Erasmo 2010, p. 84.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 384, citing Tert. De Spect. 10.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 384, citing Gell. NA 10.1.7.

- ↑ Russell, Amy (2015). The politics of public space in republican Rome. Cambridge University Press. p. 165. ISBN 9781107040496.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 384, citing Vell. Pat. 2.48.2.

- ↑ Erasmo 2010, p. 86.

- ↑ Erasmo 2020, p. 49.

- ↑ Erasmo 2020, p. 50.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 384, citing Aug. RG 20.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 384, citing Vell. Pat. 2.130.1; Tac. Ann. 3.72.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 384, citing Sen. Marc. 224; Dio 57.21.3.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 384, citing Suet. Calig. 21; Suet. Claud. 21.1; Dio 60.6.8.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 384, citing Dio 60.6.8.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 385, citing Plin. NH 33.54; Dio 62.6.1–2.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 385, citing CIL VIII, 1439.

- ↑ Richardson 1992, p. 385, citing CIL VI, 1191.

- 1 2 3 4 Richardson 1992, p. 385.

- ↑ Gregorovius, Ferdinand (1894). History of the city of Rome in the middle ages. George Bell & Sons. p. 45.

The Notitia... and the Theatre of Pompey with its 22,888 seats.

- ↑ Gagliardo & Packer 2006, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sandys 1910, p. 515.

- 1 2 3 Gagliardo & Packer 2006, pp. 95–98.

- 1 2 3 Middleton 1892, a-67, b-66–67, c-69.

- ↑ Young & Murray 1908, pp. 240–41.

- ↑ Gagliardo & Packer 2006, p. 107.

- ↑ Gagliardo & Packer 2006, p. 96.

- 1 2 "The Roman antiquities, t. 4, Plate XXXVIII. Vista of today's surplus of the Theatre of Pompey". WikiArt. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- 1 2 "Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Sketch of the Remains of the Theatrum Pompei". Theatrum Pompei Project. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012.

- ↑ Packer, James. "Excavations and Early Studies". King's Visualisation Lab. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ↑ Packer, James. "Baltard". King's Visualisation Lab. Retrieved February 11, 2016. Note: The image being referred to is Fig. 6.

- ↑ Platner 1911, p. 874.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1992, p. 169.

- ↑ Painter 2007, pp. 7–9.

- ↑ Taylor 2001, p. 159.

- ↑ Masson 1983, p. 136.

- ↑ Sear 2006, p. 1.

- ↑ Dyson 2010, p. 59.

- 1 2 Rehak 2009, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Stamper 2005, p. 89.

- ↑ Kleiner 2010, p. 57; Gagarin 2009, p. 33.

- ↑ Smith 1898, pp. 626–27.

- ↑ Barron 2009, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Vince 1984, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ This identification is preferred over the one as Temple of Iuno Curritis, because Ovid wrote in Fasti I: "Te quoque lux eadem Turni soror aede recepit/Hic, ubi Virginea Campus obitur aqua", thus placing the temple of Juturna near the Aqua Virgo, which ended at the Baths of Agrippa.

Bibliography

Modern sources

- Barron, Michael (2009). Auditorium Acoustics and Architectural Design. Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-21925-3.

- Beacham, Richard C. (1996). The Roman Theatre and Its Audience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-77914-3.

- Boëthius, Axel; et al. (1978). Etruscan and Early Roman Architecture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300052909.

- Dyson, Stephen L (2010). Rome: a living portrait of an ancient city. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9254-7.

- Erasmo, Mario (2010). Roman Tragedy: Theatre to Theatricality. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. p. 83. ISBN 9780292782136.

- Erasmo, Mario (2020). "The Theatre of Pompey: staging the self through Roman architecture". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. 65: 43–69. doi:10.2307/27031294. ISSN 0065-6801. JSTOR 27031294. S2CID 259889439.

- Gagarin, Michael (2009). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome: Seven-volume set. Vol. 1. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195170726.

- Gagliardo, Maria; Packer, James (2006). "A New Look at Pompey's Theater: History, Documentation, and Recent Excavation". Archaeological Institute of America. 110 (1).

- Kleiner, Fred S (2010). A History of Roman Art, Enhanced Edition (1 ed.). Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-0495909873.

- Kuritz, Paul (October 1987). The Making of Theatre History. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-547861-5.

- Masson, Georgina (1983). The companion guide to Rome (6th US ed.). Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-154609-0. OCLC 8907584.

- Middleton, John Henry (1892). The Remains of Ancient Rome. Vol. 2. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1-148-09793-0.

- Painter, B (March 6, 2007). Mussolini's Rome: Rebuilding. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-8002-1.

- Platner, Samuel Ball (1911). The Topography and Monuments of Ancient Rome. Boston, Allyn and Bacon.

- Rehak, Paul (2009). Imperium and Cosmos: Augustus and the Northern Campus Martius (1 ed.). Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0299220143.

- Richardson, L (1992). A new topographical dictionary of ancient Rome. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 383–85. ISBN 978-0-8018-4300-6.

- Sandys, John Edwin (1910). A Companion to Latin studies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Sear, Frank (2006). Roman Theatres: An Architectural Study. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814469-4.

- Smith, William (1898). A Concise Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. Murray.

- Stamper, John W (2005). The architecture of Roman temples: the republic to the middle empire. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521810685.

- Taylor, Rabun (2001). Public needs & private pleasures. L'Erma di Bretscheider. ISBN 978-88-8265-100-8.

- Tomlinson, Richard Allan (October 22, 1992). From Mycenae to Constantinople: the evolution of the ancient city. Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05998-5.

- Vince, Ronald W (1984). Ancient and Medieval Theatre: A Historiographical Handbook. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-24107-9.

- Young, Norwood; Murray, John (1908). Handbook for Rome and the Campagna. E. Stanford.

Ancient sources

- Plutarch (1917) [2nd century AD]. "Life of Pompey". Parallel Lives. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 5. Translated by Perrin, Bernadotte. Harvard University Press. OCLC 40115288 – via LacusCurtius.

External links

- The Theatre of Pompey

- Theatrum Pompeii at LacusCurtius (article in Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome)

- The Temple above Pompey's Theater (CJ 39:360‑366)

- Pompey’s Politics and the Presentation of His Theatre-Temple Complex, 61–52 BCE

- Roma Online Guide

![]() Media related to Theatre of Pompey at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Theatre of Pompey at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Theatre of Marcellus |

Landmarks of Rome Theatre of Pompey |

Succeeded by Domus Augustana |