The Song of Roland (French: La Chanson de Roland) is an 11th-century chanson de geste based on the Frankish military leader Roland at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in AD 778, during the reign of the Carolingian king Charlemagne. It is the oldest surviving major work of French literature. It exists in various manuscript versions, which testify to its enormous and enduring popularity in Medieval and Renaissance literature from the 12th to 16th centuries.

The epic poem written in Old French is the first[1] and one of the most outstanding examples of the chanson de geste, a literary form that flourished between the 11th and 16th centuries in Medieval Europe and celebrated legendary deeds. The date of composition is put in the period between 1040 AD and 1115 AD; an early version began around 1040 AD with additions and alterations made up until about 1115 AD. The final text contains about 4,000 lines of poetry.

Manuscripts and dating

Although set in the Carolingian era, the Song of Roland was written much later. There is a single extant manuscript of the Song of Roland in Old French, held at the Bodleian Library at Oxford.[2] It dates between 1129 and 1165 and was written in Anglo-Norman.[3] There are eight additional manuscripts and three fragments of other poems on the subject of Roland.[4]

Scholars estimate that the poem was written between approximately 1040 and 1115—possibly by a poet named Turold (Turoldus in the manuscript itself)—and that most of the alterations were completed by about 1098. Some favor the earlier dating, which allows that the narrative was inspired by the Castilian campaigns of the 1030s and that the poem was established long enough to be a major influence in the First Crusade, (1096–1099). Others favor a later dating based on their interpretations of brief references made to events of the First Crusade.

In the text, the term d'oltre mer (or l'oltremarin) occurs three times in reference to named Muslims who came from oltre mer to fight in Spain and France. Oltre mer, modern French Outremer (literally, "oversea, beyond sea, other side of the sea") is a native French term from the classical Latin roots ultra = "beyond" and mare = "sea". The name was commonly used by contemporary chroniclers to refer to the Latin Levant.[5]

The occurrence of d'oltre mer cannot reliably be interpreted as resulting from the Crusades. On the contrary, the way the term is used, referring simply to "a Muslim land", indicates that the author was writing before the Crusades. And the term was circulating in French prior to the time of the Crusades—referring to the far, or eastern, end of the Mediterranean. The bulk of the poem itself dates from before the Crusades. Still, there are a few terms where questions remain about their being late to the poem, i.e., added shortly after the first Crusade started in 1096.

After two manuscripts were found in 1832 and 1835, the Song of Roland became recognized as France's national epic when an edition was published in 1837.[6]

Critical opinions

Oral performance compared to manuscript versions

Scholarly consensus has long accepted that The Song of Roland differed in its presentation depending on whether transmission was oral or textual; namely, although a number of different versions of the song—containing varying material and episodes—would have been performed orally, the transcription to manuscript resulted in greater cohesiveness across those versions.

Early editors of The Song of Roland, informed in part by patriotic desires to produce a distinctly French epic, could thus overstate the textual cohesiveness of the Roland tradition. This point is expressed by Andrew Taylor, who notes, "[T]he Roland song was, if not invented, at the very least constructed. By supplying it with an appropriate epic title, isolating it from its original codicological context, and providing a general history of minstrel performance in which its pure origin could be located, the early editors presented a 4,002 line poem as sung French epic".[7]

AOI

Certain lines of the Oxford manuscript end with the letters "AOI". The meaning of this word or annotation is unclear. Many scholars have hypothesized that the marking may have played a role in public performances of the text, such as indicating a place where a jongleur would change the tempo. Contrarily, Nathan Love believes that "AOI" marks locations where the scribe or copyist is signaling that he has deviated from the primary manuscript: ergo, the mark indicates the source is a non-performance manuscript.[8]

Plot

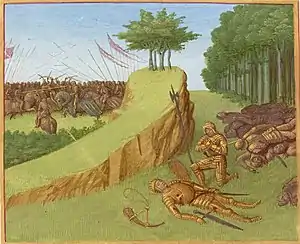

From a historical perspective, the Song of Roland's account of the Battle of Roncesvalles is impossible. According to Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni, written in the late eighth century, the antagonists are Basques who were incited to attack Charlemagne's army to avenge the looting of Pamplona. The following is what is depicted in the poem itself, not subsequent historical accounts.

Charlemagne's army is fighting the Muslims in Spain. They have been there for seven years, and the last city standing is Saragossa, held by the Muslim King Marsile. Threatened by the might of Charlemagne's army of Franks, Marsile seeks advice from his wise man, Blancandrin, who counsels him to conciliate the Emperor, offering to surrender and giving hostages. Accordingly, Marsile sends out messengers to Charlemagne, promising treasure and Marsile's conversion to Christianity if the Franks will go back to Francia.

Charlemagne and his men, tired of fighting, accept his peace offer and select a messenger to Marsile's court. The protagonist Roland, Charlemagne's nephew, nominates his stepfather Ganelon as messenger. Ganelon, who fears being murdered by the enemy and accuses Roland of intending this, takes revenge by informing the Saracens of a way to ambush the rear guard of Charlemagne's army, led by Roland, as the Franks re-enter Francia through the mountain passes.

As Ganelon predicted, Roland leads the rear guard, with the wise and moderate Oliver and the fierce Archbishop Turpin. The Muslims ambush them at Roncesvalles and the Christians are overwhelmed. Oliver pleads with Roland to blow his horn to call for help, but Roland tells him that blowing his horn in the middle of the battle would be an act of cowardice. If Roland continues to refuse, Oliver will not let Roland see his sister again whom Roland loves the most. However, Archbishop Turpin intervenes and tells them that the battle will be fatal for all of them and so instructs Roland to blow his horn oliphant (the word is an old alternative to "elephant", and was used to refer to a hunting horn made from an elephant tusk) to call for help from the Frankish army. The emperor hears the call on their way to Francia. Charlemagne and his noblemen gallop back even though Count Ganelon tries to trick them.

The Franks fight well, but are outnumbered, until almost all Roland's men are dead and he knows that Charlemagne's army can no longer save them. Despite this, he blows his olifant to summon revenge, with such vigor that his temples start to bleed. After a few more fights, Roland succumbs to his wounds and dies a martyr's death. Angels take his soul to Paradise.

When Charlemagne and his men reach the battlefield, they find the dead bodies of Roland's men, who have been utterly annihilated. They pursue the Muslims into the river Ebro, where the Muslims drown. Meanwhile, Baligant, the powerful emir of Babylon, has arrived in Spain to help Marsile. His army encounters that of Charlemagne at Roncesvalles, where the Christians are burying and mourning their dead. The Franks fight valiantly. When Charlemagne kills Baligant, the Muslim army scatters and flees, leaving the Franks to conquer Saragossa. With Marsile's wife Bramimonde, Queen of Saragossa, Charlemagne and his men ride back to Aix, their capital in Francia.

The Franks discover Ganelon's betrayal and keep him in chains until his trial, where Ganelon argues that his action was legitimate revenge, not treason. While the council of barons assembled to decide the traitor's fate is initially swayed by this claim, partially out of fear of Ganelon's friend Pinabel who threatens to fight anyone who judges Ganelon guilty, one man, Thierry, argues that because Roland was serving Charlemagne when Ganelon delivered his revenge on him, Ganelon's action constitutes a betrayal.

Pinabel challenges Thierry to trial by combat. By divine intervention, Thierry kills Pinabel. By this the Franks are convinced of Ganelon's treason. Thus, he is torn apart by having four galloping horses tied one to each arm and leg and thirty of his relatives are hanged. Bramimonde converts to Christianity, her name changing to Juliana. While sleeping, Charlemagne is told by Gabriel to ride to help King Vivien and bemoans his life.

Form

The song is written in stanzas of irregular length known as laisses. The lines are decasyllabic (containing ten syllables), and each is divided by a strong caesura which generally falls after the fourth syllable. The last stressed syllable of each line in a laisse has the same vowel sound as every other end-syllable in that laisse. The laisse is therefore an assonal, not a rhyming stanza.

On a narrative level, the Song of Roland features extensive use of repetition, parallelism, and thesis-antithesis pairs. Roland proposes Ganelon for the dangerous mission to Sarrogossa; Ganelon designates Roland to man the rearguard. Charlemagne is contrasted with Baligant.[9] Unlike later Renaissance and Romantic literature, the poem focuses on action rather than introspection. The characters are presented through what they do, not through what they think or feel.

The narrator gives few explanations for characters' behaviour. The warriors are stereotypes defined by a few salient traits; for example, Roland is loyal and trusting while Ganelon, though brave, is traitorous and vindictive.

The story moves at a fast pace, occasionally slowing down and recounting the same scene up to three times but focusing on different details or taking a different perspective each time. The effect is similar to a film sequence shot at different angles so that new and more important details come to light with each shot.

Characters

Principal characters

- Baligant, emir of Babylon; Marsile enlists his help against Charlemagne.

- Blancandrin, wise pagan; suggests bribing Charlemagne out of Spain with hostages and gifts, and then suggests dishonouring a promise to allow Marsile's baptism.

- Bramimonde, Queen of Zaragoza, King Marsile's wife; captured and converted by Charlemagne after the city falls.

- Charlemagne, King of the Franks; his forces fight the Saracens in Spain. Wields the sword Joyeuse.

- Ganelon, treacherous lord and Roland's stepfather who encourages Marsile to attack the French army. Wields the sword Murgleis.

- King Marsile, Saracen king of Spain; Roland wounds him and he dies of his wound later.

- Naimon, Charlemagne's trusted adviser.

- Oliver, Roland's friend; mortally wounded by Margarice. He represents wisdom.

- Roland, the hero of the Song and nephew of Charlemagne. Wields the sword Durandal. Leads the rear guard of the French forces; bursts his temples by blowing his olifant-horn, wounds from which he eventually dies facing the enemy's land.

- Turpin, Archbishop of Rheims, represents the force of the Church. Wields the sword Almace.

Secondary characters

- Aude, the fiancée of Roland and Oliver's sister

- Basan, Frankish baron, murdered while serving as Ambassador of Marsile.

- Bérengier, one of the twelve paladins killed by Marsile's troops; kills Estramarin; killed by Grandoyne.

- Besgun, chief cook of Charlemagne's army; guards Ganelon after Ganelon's treachery is discovered.

- Geboin, guards the Frankish dead; becomes leader of Charlemagne's 2nd column.

- Godefroy, standard bearer of Charlemagne; brother of Thierry, Charlemagne's defender against Pinabel.

- Grandoyne, fighter on Marsile's side; son of the Cappadocian King Capuel; kills Gerin, Gerier, Berenger, Guy St. Antoine, and Duke Astorge; killed by Roland.

- Hamon, joint Commander of Charlemagne's Eighth Division.

- Lorant, Frankish commander of one of the first divisions against Baligant; killed by Baligant.

- Milon, guards the Frankish dead while Charlemagne pursues the Saracen forces.

- Ogier, a Dane who leads the third column in Charlemagne's army against Baligant's forces.

- Othon, guards the Frankish dead while Charlemagne pursues the Saracen forces.

- Pinabel, fights for Ganelon in the judicial combat.

- Thierry, fights for Charlemagne in the judicial combat.

Durandal

According to the Song of Roland, the legendary sword called Durandal was first given to Charlemagne by an angel. It contained one tooth of Saint Peter, blood of Saint Basil, hair of Saint Denis, and a piece of the raiment of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and was supposedly the sharpest sword in all existence. In the story of the Song of Roland, the weapon is given to Roland, and he uses it to defend himself single-handedly against thousands of Muslim attackers. According to one 12th-century legend from the French town of Rocamadour, Roland threw the sword into a cliffside.[10] A replication of the legendary sword can be found there, embedded into the cliff-face next to the town's sanctuary.[11]

Historical adaptations

A Latin poem, Carmen de Prodicione Guenonis, was composed around 1120, and a Latin prose version, Historia Caroli Magni (often known as "The Pseudo-Turpin") even earlier. Around 1170, a version of the French poem was translated into the Middle High German Rolandslied by Konrad der Pfaffe[9] (formerly thought to have been the author of the Kaiserchronik). In his translation Konrad replaces French topics with generically Christian ones. The work was translated into Middle Dutch in the 13th century.

It was also rendered into Occitan verse in the 14th- or 15th-century poem of Ronsasvals, which incorporates the later, southern aesthetic into the story. An Old Norse version of the Song of Roland exists as Karlamagnús saga, and a translation into the artificial literary language of Franco-Venetian is also known; such translations contributed to the awareness of the story in Italy. In 1516 Ludovico Ariosto published his epic Orlando Furioso, which deals largely with characters first described in the Song of Roland.

There is also Faroese adoption of this ballad named "Runtsivalstríðið" (Battle of Roncevaux), and a Norwegian version called "Rolandskvadet".[12] The ballad is one of many sung during the Faroese folkdance tradition of chain dancing.

Modern adaptations

Joseph Haydn and Nunziato Porta's opera, Orlando Paladino (1782), the most popular of Haydn's operas during his lifetime, is based loosely on The Song of Roland via Ariosto's version, as are Antonio Vivaldi and Grazio Braccioli's 1727 opera and their earlier 1714 version.

The Chanson de Roland has an important place in the background of Graham Greene's The Confidential Agent, published in 1939. The book's protagonist had been a Medieval scholar specialising in this work, until the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War forced him to become a soldier and secret agent. Throughout the book, he repeatedly compares himself and other characters with the characters of "Roland". Particularly, the book includes a full two pages of specific commentary, which is relevant to its 20th-century plot line: "Oliver, when he saw the Saracens coming, urged Roland to blow his horn and fetch back Charlemagne – but Roland wouldn't blow. A big brave fool. In war one always chooses the wrong hero. Oliver should have been the hero of that song, instead of being given second place with the blood-thirsty Bishop Turpin. [...] In the Oxford version Oliver is reconciled in the end, he gives Roland his death-blow by accident, his eyes blinded by wounds. [But] the story had been tidied up. In truth, Oliver strikes his friend down in full knowledge – because of what he has done to his men, all the wasted lives. Oliver dies hating the man he loves – the big boasting courageous fool who was more concerned with his own glory than with the victory of his faith. This makes the story tragedy, not just heroics".[13]

It is also adapted by Stephen King, in the Dark Tower series in which Roland Deschain wishes to save the Dark Tower from the Crimson King, itself inspired by Robert Browning's "Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came".

The Song of Roland is part of the Matter of France (the Continental counterpart to the Arthurian legendarium known as the Matter of Britain), and related to Orlando Furioso. The names Roland and Orlando are cognates.

Emanuele Luzzati's animated short film, I paladini di Francia, together with Giulio Gianini, in 1960, was turned into the children's picture-story book, with verse narrative, I Paladini de Francia ovvero il tradimento di Gano di Maganz, which translates literally as "The Paladins of France or the treachery of Ganelon of Mainz" (Ugo Mursia Editore, 1962). This was then republished, in English, as Ronald and the Wizard Calico (1969). The Picture Lion paperback edition (William Collins, London, 1973) is a paperback imprint of the Hutchinson Junior Books edition (1969), which credits the English translation to Hutchinson Junior Books.

Luzzati's original verse story in Italian is about the plight of a beautiful maiden called Biancofiore – White Flower, or Blanchefleur – and her brave hero, Captain Rinaldo, and Ricardo and his paladins – the term used for Christian knights engaged in Crusades against the Saracens and Moors. Battling with these good people are the wicked Moors – North African Muslims and Arabs – and their Sultan, in Jerusalem. With the assistance of the wicked and treacherous magician, Gano of Maganz, Biancofiore is stolen from her fortress castle, and taken to become the reluctant wife of the Sultan. The catalyst for victory is the good magician, Urlubulu, who lives in a lake, and flies through the air on the back of his magic blue bird. The English translators, using the original illustrations, and the basic rhyme patterns, slightly simplify the plot, changing the Christians-versus-Muslim-Moors conflict into a battle between good and bad magicians and between golden knights and green knights. The French traitor in The Song of Roland, who is actually Roland's cowardly step-father, is Ganelon – very likely the inspiration for Luzzati's traitor and wicked magician, Gano. Orlando Furioso (literally, Furious or Enraged Orlando, or Roland), includes Orlando's cousin, the paladin Rinaldo, who, like Orlando, is also in love with Angelica, a pagan princess. Rinaldo is, of course, the Italian equivalent of Ronald. Flying through the air on the back of a magic bird is equivalent to flying on a magic hippogriff.

It appears in the 1994 video game Marathon, by Bungie, in the 13th level. Durandal is also the name of the main antagonist of the game.

On 22 July 2017 Michael Eging and Steve Arnold released a novel, The Silver Horn Echoes: A Song of Roland, inspired by the La Chanson de Roland. This work is more closely based on a screenplay written by Michael Eging in 2008, simply known as "Song of Roland" and first optioned to Alan Kaplan at Cine LA that same year. The book explores the untold story of how Roland finds himself at Ronceveaux, betrayed by Ganelon and facing the expansive Saragossan host. Primary characters in the novel include Charles (Charlemagne), Ganelon, Bishop Turpin, Oliver, Aude, Marsilion, Blancandarin and others recognizable from the poem. Introduced in this tale are additional characters that inject intrigue and danger to the story, including Charles oldest son, Pepin, Marsilion's treacherous son, Saleem, and the scheming Byzantine emissary, Honorius. The cover artwork was hand painted by Jordan Raskin. The authors determined when writing both the screenplay and the novel to remain in the world created by the poem; thus, Charles remains an older man near the end of his long reign rather than in 778 when the attack on the rearguard actually occurred. Further, this novel bookends the story with William the Conqueror's use of the poem as a motivator for Norman forces prior to the Battle of Hastings in 1066.[14]

In 2019, German folk rock band dArtagnan released "Chanson de Roland", a modern adaptation of the Song of Roland.[15] It has garnered over 1.8 million views on YouTube.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "The Song of Roland". FordhamUniversity.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-02-04. Retrieved 2015-02-04.

- ↑ (in French) La Chanson de Roland on Dictionnaire Étymologique de l'Ancien Français

- ↑ Short, Ian (1990). "Introduction". La Chanson de Roland. France: Le Livre de Poche. pp. 5–20.

- ↑ "La Chanson de Roland", Archives de littérature du Moyen Âge

- ↑ Lambert of Ardres, for instance, spoke of "ultramarinarum partium gestis" ("deeds done in the lands beyond the sea", Chronicon Ghisnense et Ardense, ed. Denis-Charles Godefroy Ménilglaise, Paris 1855, pp. 215–17) when referring to the Crusades. Likewise, Thibaut of Champagne, writing about a century later, also used the "outremer" reference as self-explanatory (Les chansons de croisade avec leurs mélodies, ed. Joseph Bédier & Pierre Aubry, Paris 1909, p. 171)

- ↑ Gaunt, Simon; Pratt, Karen (2016). The Song of Roland, and Other Poems of Charlemagne. New York: Oxford University Press. p. xi. ISBN 978-0-19-965554-0.

- ↑ Taylor, Andrew, "Was There a Song of Roland?" Speculum 76 (January 2001): 28–65

- ↑ Love, Nathan (1984). "AOI in the Chanson de Roland: A divergent hypothesis". Olifant. Société Rencesvals. 10 (4).

- 1 2 Brault, Gerard J., Song of Roland: An Analytical Edition: Introduction and Commentary, Penn State Press, 2010 ISBN 9780271039145

- ↑ "The sword of Rocamadour". quercy.net (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ↑ "Rocamadour: Roland's sword, Durandal, leaves for the Cluny museum". ladepeche.fr (in French). Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- ↑ Part of Runtsivalstríðið with Dansifelagið í Havn

- ↑ "The Confidential Agent", Part 1, Ch. 2, quoted in "Graham Greene: an approach to the novels" by Robert Hoskins, p. 122

- ↑ Author's notes, The Silver Horn Echoes: A Song of Roland, iUniverse, July 2017 (http://www.iuniverse.com/Bookstore/BookDetail.aspx?BookId=SKU-000995830)

- ↑ "Chanson de Roland – dArtagnan: Lyrics & Translation". musinfo.net. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

Further reading

- Brault, Gerard J. Song of Roland: An Analytical Edition: Introduction and Commentary (Penn State Press, 2010).

- DiVanna, Isabel N. "Politicizing national literature: the scholarly debate around La chanson de Roland in the nineteenth century." Historical Research 84.223 (2011): 109–134.

- Jones, George Fenwick. The ethos of the song of Roland (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1963).

- Vance, Eugene. Reading the Song of Roland (1970).

External links

- The Song of Roland at Project Gutenberg (English translation of Charles Kenneth Scott Moncrieff)

- The Song of Roland--(Dorothy L. Sayers) at Faded Page (Canada)

The Song of Roland public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Song of Roland public domain audiobook at LibriVox- La Chanson de Roland (Old French)

- The Romance of the Middle Ages: The Song of Roland, discussion of Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Digby 23, audio clip, and discussion of the manuscript's provenance.

- MS Digby 23b, Digital facsimile of the earliest manuscript of the Chanson de Roland.

- MS Digby 23 Catalogue record in Medieval Manuscripts of Oxford Libraries

- Old French Audio clips of a reading of The Song of Roland in Old French

- BBC Radio In Our Time podcast.

- Timeless Myths: Song of Roland

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.