July 8, 1947, issue of the Roswell Daily Record, featured a story announcing the "capture" of a "flying saucer" from a ranch near Roswell | |

| Date | June & July 1947 |

|---|---|

| Location | Lincoln County, New Mexico, US |

| Coordinates | 33°57′01″N 105°18′51″W / 33.95028°N 105.31417°W |

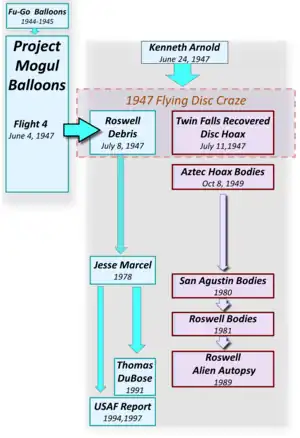

The Roswell incident is a collection of events and myths surrounding the 1947 crash of a United States Army Air Forces balloon, near Roswell, New Mexico. Operated from the nearby Alamogordo Army Air Field and part of the top secret Project Mogul, the balloon's purpose was remote detection of Soviet nuclear tests.[1] After metallic and rubber debris was recovered by Roswell Army Air Field personnel, the United States Army announced their possession of a "flying disc". This announcement made international headlines but was retracted within a day. Obscuring the true purpose and source of the crashed balloon, the Army subsequently stated that it was a conventional weather balloon.

| 1947 flying disc craze |

|---|

| Events |

In 1978, retired Air Force officer Jesse Marcel revealed that the Army's weather balloon claim had been a cover story, but added to that his speculation that the debris was of extraterrestrial origin. Popularized by the 1980 book The Roswell Incident, this speculation became the basis for long-lasting and increasingly complex and contradictory ufology conspiracy theories, which over time expanded the incident to include governments concealing evidence of extraterrestrial beings, grey aliens, multiple crashed flying saucers, alien corpses and autopsies, and the reverse engineering of extraterrestrial technology, none of which have any factual basis.

Despite the lack of evidence, many UFO proponents claim that the Roswell debris was derived from an alien craft, and accuse the US government of a cover-up. The conspiracy narrative has become a trope in science fiction literature, film, and television. The town of Roswell leverages this to promote itself as a destination for UFO-associated tourism.

1947 military balloon crash

A military balloon crashed near Roswell, New Mexico,[2] during what historian Kathryn S. Olmsted describes as "the first summer of the Cold War".[3] By 1947, the United States's top-secret Project Mogul had launched thousands of balloons carrying devices to listen for Soviet atomic tests.[4] On June 4, 1947, researchers at Alamogordo Army Air Field launched a long train of these balloons and lost contact within 17 miles (27 km) of W.W. "Mac" Brazel's ranch.[5] Brazel discovered tinfoil, rubber, tape, and thin wooden beams scattered across several acres of his ranch in mid-June.[6][7] That June, Kenneth Arnold's account of what became known as flying saucers incited a wave of over 800 sightings.[8] With no phone or radio, Brazel was initially unaware of the ongoing flying disc craze,[9] but he was told about it when visiting his uncle in Corona, New Mexico on July 5; the next day he informed Sheriff George Wilcox of the debris he had found.[10] Wilcox called Roswell Army Air Field (RAAF), who assigned Major Jesse Marcel and Captain Sheridan Cavitt to return with Brazel and gather the material from the ranch.[11]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

On July 8, RAAF public information officer Walter Haut issued a press release stating that the military had recovered a "flying disc" near Roswell.[12] Robert Porter, an RAAF flight engineer, was part of the crew who loaded what he was "told was a flying saucer" onto the flight bound for Fort Worth Army Air Field (FWAAF). He described the material – packaged in wrapping paper when he received it – as lightweight and not too large to fit inside the trunk of a car.[13][14] After station director George Walsh broke the news over Roswell radio station KSWS and relayed it to the Associated Press, his phone lines were overwhelmed. He later recalled, "All afternoon, I tried to call Sheriff Wilcox for more information, but could never get through to him [...] Media people called me from all over the world."[15]

The many rumors regarding the flying disc became a reality yesterday when the intelligence office of the 509th Bomb group of the Eighth Air Force, Roswell Army Air Field, was fortunate enough to gain possession of a disc through the cooperation of one of the local ranchers and the sheriff's office of Chaves County.

The flying object landed on a ranch near Roswell sometime last week. Not having phone facilities, the rancher stored the disc until such time as he was able to contact the sheriff's office, who in turn notified Maj. Jesse A. Marcel of the 509th Bomb Group Intelligence Office.— Associated Press (July 8, 1947)[16]

Media interest in the case dissipated soon after a press conference where General Roger Ramey, his chief of staff Colonel Thomas Dubose, and weather officer Irving Newton identified the material as pieces of a weather balloon.[6][17] Newton told reporters that similar radar targets were used at about 80 weather stations.[7][18] The small number of subsequent news stories offered mundane and prosaic accounts of the crash.[17][6] On July 9, the Roswell Daily Record highlighted that no engine or metal parts had been found in the wreckage.[19] Brazel told the Record that the debris consisted of a rubber strips, "tinfoil, paper, tape, and sticks"[19][20] Brazel said he paid little attention to it but returned later with his wife and daughter to gather up some of the debris.[19][21] When interviewed in Fort-Worth, Texas, Marcel described the wreckage as "parts of the weather device" and "patches of tinfoil and rubber."[7] The 1947 official account omitted any connection to Cold War military programs.[22] Major Wilbur D. Pritchard, then stationed at Alamogordo Army Air Field, would later describe the weather balloon story as "an attempt to deflect attention from the top secret Mogul project."[23]

UFO conspiracy theories (1947–1978)

The Roswell incident remained relatively obscure for three decades.[24] Reporting on the incident ceased soon after the government provided a mundane explanation,[25] and broader reporting on flying saucers declined rapidly after the Twin Falls saucer hoax.[26] Just days after the Roswell incident, a widely reported crashed disc from Twin Falls, Idaho, was found to be a hoax created by four teenagers using parts from a jukebox.[27][28]

Nevertheless, belief in a UFO cover-up by the US government became widespread in this period.[29] During Roswell's decades of obscurity, a UFO mythology developed fueled by hoaxes, legends, and stories of crashed spaceships and alien bodies in New Mexico.[30] In 1947, many Americans attributed flying saucers to unknown military aircraft.[3] In the decades between the initial debris recovery and the emergence of Roswell theories, flying saucers became synonymous with alien spacecraft.[31] Trust in the US government declined and acceptance of conspiracy theories became widespread.[32] UFO believers accused the government of a "Cosmic Watergate".[33] The 1947 incident was reinterpreted to fit the public's increasingly conspiratorial outlook.[34][35]

Aztec crashed saucer hoax

The Aztec, New Mexico crashed saucer hoax introduced stories of recovered alien bodies that would later become associated with Roswell.[36][37] It achieved broad exposure when the con artists behind it convinced Variety columnist Frank Scully to cover their fictitious crash.[38] The hoax narrative included small grey humanoid bodies, metal stronger than any found on Earth, and indecipherable writing – these elements appeared in later versions of the Roswell myth.[36][39] In retellings of the Roswell incident, the mundane debris reported at the actual crash site was replaced with the Aztec hoax's fantastical alloys.[40][41] By the time Roswell returned to media attention, grey aliens had become a part of American culture through the Barney and Betty Hill incident.[42][43] In a 1997 Roswell report, Air Force investigator James McAndrew wrote that "even with the exposure of this obvious fraud, the Aztec story is still revered by UFO theorists. Elements of this story occasionally reemerge and are thought to be the catalyst for other crashed flying saucer stories, including the Roswell Incident."[44]

Hangar 18

"Hangar 18" is a non-existent location that many later conspiracy theories allege housed extraterrestrial craft or bodies recovered from Roswell.[45] The idea of alien corpses from a crashed ship being stored in an Air Force morgue at the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base was mentioned in the 1966 book Incident at Exeter,[46][47] and expanded by a 1968 science-fiction novel The Fortec Conspiracy.[47] Fortec was about a fictional cover-up by the Air Force unit charged with reverse-engineering other nations' technical advancements.[47]

In 1974, science-fiction author and conspiracy theorist Robert Spencer Carr alleged that alien bodies recovered from the Aztec crash were stored in "Hangar 18" at Wright-Patterson.[48] Carr claimed that his sources had witnessed the alien autopsy,[49] another idea later incorporated into the Roswell narrative.[50][51] The Air Force explained that no "Hangar 18" existed at the base, noting a similarity between Carr's story and the fictional Fortec Conspiracy.[52] Hangar 18 (1980), which dramatized Carr's claims, was described as "a modern-day dramatization" of Roswell by the film's director James L. Conway,[53] and as "nascent Roswell mythology" by folklorist Thomas Bullard.[54] Decades later, Carr's son recalled that his father had been a habitual liar who often "mortified my mother and me by spinning preposterous stories in front of strangers... [tales of] befriending a giant alligator in the Florida swamps, and sharing complex philosophical ideas with porpoises in the Gulf of Mexico."[55]

Roswell conspiracy theories (1978–1994)

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Interest in the Roswell incident was rekindled after ufologist Stanton Friedman interviewed Jesse Marcel in February 1978.[56] Marcel had accompanied the Roswell debris from the ranch to the Fort Worth press conference. In the 1978 interview, Marcel stated that the "weather balloon" explanation from the press conference was a cover story,[57] and that he now believed the debris was extraterrestrial.[58] On December 19, 1979, Marcel was interviewed by Bob Pratt of the National Enquirer,[59] and the tabloid brought large-scale attention to the Marcel story the following February.[60][61] On September 20, 1980, the TV series In Search of... aired an interview where Marcel described his participation in the 1947 press conference:[24]

They wanted some comments from me, but I wasn't at liberty to do that. So, all I could do is keep my mouth shut. And General Ramey is the one who discussed – told the newspapers, I mean the newsman, what it was, and to forget about it. It is nothing more than a weather observation balloon. Of course, we both knew differently.[62]

The 1980 book The Roswell Incident popularized Marcel's account and added the claimed discovery of alien bodies on the Plains of San Agustin,[63] approximately 150 miles west of the original debris site.[64] Marcel had consistently denied the presence of bodies.[65] Major Marcel's son, Jesse A. Marcel Jr. M.D., maintained throughout his life that, when he was 10 years old, his father had shown him alien debris recovered from the Roswell crash site, including, "a small beam with purple-hued hieroglyphics on it".[66][67]

Between 1978 and the early 1990s, UFO researchers such as Stanton T. Friedman, William Moore, and the team of Kevin D. Randle and Donald R. Schmitt interviewed several dozen people who claimed to have had a connection with the events at Roswell in 1947.[68]

In 1981, tabloid The Globe told stories of bodies being brought to Roswell.[70] In 1989, mortician Glenn Dennis recounted a tale of a nurse who had assisted in an alien autopsy.[71]

In 1991, retired Brigadier General Thomas DuBose corroborated Marcel's claims that the weather balloon was a cover story, while both men consistently denied the existence of bodies.[72] In 1994, the Air Force identified the material as part of a top secret atomic surveillance balloon from Project Mogul launched on June 4 which had last been tracked near Corona.[73][74]

The Roswell Incident

In October 1980, Marcel's story was featured in the book The Roswell Incident by Charles Berlitz and William Moore.[75] The authors had previously written popular books on fringe topics such as the Philadelphia Experiment and the Bermuda Triangle.[76][77]

The book argues that an extraterrestrial craft was flying over the New Mexico desert to observe nuclear weapons activity when a lightning strike killed the alien crew and, that after discovering the crash, the US government engaged in a cover-up.[76]

- Claims about the debris

The Roswell Incident featured accounts of the debris described by Marcel as "nothing made on this earth."[78] Additional accounts by Bill Brazel,[79] son of rancher Mac Brazel, neighbor Floyd Proctor[80] and Walt Whitman Jr.,[81] son of newsman W. E. Whitman who had interviewed Mac Brazel, suggested the material Marcel recovered had super-strength not associated with a weather balloon. Anthropologist Charles Zeigler described the 1980 book as "version 1" of the Roswell myth.[4] Berlitz and Moore's narrative was dominant until the late 1980s when other authors, attracted by the commercial potential of writing about Roswell, started producing rival accounts.[82]

The book introduced the contention that the debris recovered by Marcel at the Foster ranch, visible in photographs showing Marcel posing with the debris, was substituted for the debris from a weather device as part of a cover-up.[83][84] The book also claimed that the debris recovered from the ranch was not permitted a close inspection by the press. The efforts by the military were described as being intended to discredit and "counteract the growing hysteria towards flying saucers".[85]

The authors claimed to have interviewed over 90 witnesses, though the testimony of only 25 appears in the book. Only seven of these people claimed to have seen the debris. Of these, five claimed to have handled it.[86] Two accounts of witness intimidation were included in the book, including the incarceration of Mac Brazel.[87]

Berlitz and Moore prioritized Marcel's description of the material over the mundane description provided by Captain Sheridan Cavitt.[88] Later authors would selectively quote Cavitt's assertion that the debris was not a German rocket or Japanese balloon bomb.[89] When comparing Marcel's statements, Philip J. Klass found many of Marcel's claims to be contradictory or inaccurate.[90]

- First claim of alien bodies

(1947)

(1947)

The book was the first to introduce the controversial second-hand stories of civil engineer Grady "Barney" Barnett and a group of archaeology students from an unidentified university encountering wreckage and "alien bodies" while on the Plains of San Agustin before being escorted away by the Army.[92] The second-hand Barnett stories, set 150 miles to the west of Corona, were described by ufologists as the "one aspect of the account that seemed to conflict with the basic story about the retrieval of highly unusual debris from a sheep ranch outside Corona, New Mexico, in July 1947".[93]

Many alleged first-hand accounts of the Roswell incident actually contain information from the Aztec, New Mexico, UFO incident,[36] a hoaxed flying saucer crash which gained national notoriety after being promoted by journalist Frank Scully in his articles and a 1950 book Behind the Flying Saucers.[37]

Majestic 12 hoax

On May 29, 1987, a team consisting of Stanton Friedman, William Moore, and television producer Jaime Shandera released the "Majestic Twelve documents". On December 11, 1984, Shandera had received the documents in the mail from an unknown source.[94] The MJ-12 documents purported to be a 1952 briefing prepared for President Eisenhower. They have been called "version 2" of the Roswell story.[95][96] In this variant, the bodies are ejected from the craft shortly before it exploded over the ranch. The propulsion unit is destroyed and the government concludes the ship was a "short range reconnaissance craft". The following week, the bodies are recovered some miles away, decomposing from exposure and predators. [97]

On July 1, 1989, Moore gave a speech at the MUFON annual symposium where he acknowledged spreading "disinformation", claiming he did so on behalf of the Air Force Office of Special Investigations.[98][99] By 1991, the documents were exposed as forgeries, with a signature and stray marks copied from a different letter.[100]

Role of Glenn Dennis

| External videos | |

|---|---|

On August 5, 1989, Stanton Friedman interviewed former mortician Glenn Dennis. Dennis claimed to have received "four or five calls" from the Air Base with questions about body preservation and inquiries about small or hermetically sealed caskets; he further claimed that a local nurse told him she had witnessed an "alien autopsy". Glenn Dennis has been called the "star witness" of the Roswell incident.[101]

On September 20, 1989, an episode of Unsolved Mysteries included second-hand stories of "Barney" Barnett seeing alien bodies captured by the Army and pilot "Pappy" Henderson transporting bodies from Roswell to Texas. The episode was watched by 28 million people.[70]

In September 1991, Dennis co-founded a UFO museum in Roswell along with former RAAF public affairs officer Walter Haut and Max Littell, a real estate salesman.[102] Dennis appeared in multiple books and documentaries repeating his story. In 1994, Dennis's tale was dramatized in the made-for-TV movie Roswell and by the television show Unsolved Mysteries.[103][104]

.jpg.webp)

Dennis provided false names for the nurse who allegedly witnessed the autopsy.[105] Presented with evidence that no such person existed, Dennis admitted to lying about the name.[106] Karl Pflock observed that Dennis's story "sounds like a B-grade thriller conceived by Oliver Stone."[107] Scientific skeptic author Brian Dunning said that Dennis cannot be regarded as a reliable witness, considering that he had seemingly waited over 40 years before he started recounting a series of unconnected events. Such events, Dunnings argues, were then arbitrarily joined to form what has become the most popular narrative of the alleged alien crash.[108] Prominent UFO researchers, including Pflock and Kevin Randle, have become convinced that no bodies were recovered from the Roswell crash.[109]

Competing accounts and schism

The early 1990s saw a proliferation of competing accounts.

UFO Crash at Roswell

.jpeg.webp)

In 1991, Kevin Randle and Donald Schmitt published UFO Crash at Roswell, which has been called "version 3" of the Roswell story.[110] They added testimony from 100 new witnesses,[82] including those who reported an elaborate military cordon and debris recovery operation at the Foster ranch. The book included the new claims of a "gouge ... that extended four or five hundred feet [120 or 150 m]" at the ranch.[111]

Randle and Schmitt reported Gen. Arthur Exon had been directly aware of debris and bodies, but Exon disputed his depiction, saying his comments had been based exclusively on second-hand rumors.[112] The 1991 book sold 160,000 copies and served as the basis for the 1994 television film Roswell.[113] Also in 1991, retired USAF Brigadier General Thomas DuBose, who had posed with debris for press photographs in 1947, publicly acknowledged the weather balloon cover story, corroborating Marcel's previous admissions.[72]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Glenn Dennis's claims of an alien autopsy was detailed in the book along with Grady Barnett's "alien body" accounts.[115][116] However the dates and locations were changed from Barnett's accounts found in 1980's The Roswell Incident. In this new account, Brazel was described as leading the Army to a second crash site on the ranch, at which point the Army personnel were supposedly "horrified to find civilians [including Barnett] there already."[117]

Though hundreds of people were interviewed by various researchers, only a few of these people claimed to have seen debris or aliens. Most witnesses were just repeating the claims of others. Pflock notes that of these 300-plus individuals reportedly interviewed for UFO Crash at Roswell (1991), only 41 can be "considered genuine first- or second-hand witnesses" and only 23 can be "reasonably thought to have seen physical evidence, debris". Of these, only seven have asserted anything suggestive of otherworldly origins for the debris.[118]

Crash at Corona

In 1992, Stanton Friedman released Crash at Corona, co-authored with Don Berliner.[113][119] The book, later termed "version 4" of the Roswell story, introduced new "witnesses" and added to the narrative by doubling the number of flying saucers to two, and the number of aliens to eight – two of which were said to have survived and been taken into custody by the government.[113] [120] Friedman interviewed Lydia Sleppy, a former teletype operator at the KOAT station in Albuquerque, New Mexico,[121] who claimed that she was typing a story about the wreckage as dictated by reporter Johnny McBoyle until interrupted by an incoming message, allegedly from the FBI, ordering her to end communications.[122]

The Truth About the UFO Crash at Roswell

In 1994, Randle and Schmitt authored another book, The Truth About the UFO Crash at Roswell which included a claim that alien bodies were taken by cargo plane to be viewed by Dwight D. Eisenhower.[113] Zeigler refers to the 1994 book as 'version 5' of the Roswell story.[120]

Attempt to reconcile diverging narratives

The existence of so many differing accounts led to a schism among ufologists about the events at Roswell.[123] The Center for UFO Studies (CUFOS) and the Mutual UFO Network (MUFON), two leading UFO societies, disagreed in their views of the various scenarios presented by Randle–Schmitt and Friedman–Berliner; several conferences were held to try to resolve the differences. One issue under discussion was where Barnett was when he saw the alien craft he was said to have encountered. A 1992 UFO conference attempted to achieve a consensus among the various scenarios portrayed in Crash at Corona and UFO Crash at Roswell; however, the publication of The Truth About the UFO Crash at Roswell "resolved" the Barnett problem by simply ignoring Barnett and citing a new location for the alien craft recovery, including a new group of archaeologists not connected to the ones the Barnett story cited.[123]

Air Force response

Under pressure from a New Mexico congressman and the General Accounting Office (GAO),[124] the Air Force provided official responses to Roswell conspiracy theories during the mid-1990s.[125] The initial 1994 USAF report, admitted that the weather balloon explanation was a cover story but for Project Mogul a military surveillance program.[126][127] The following year, The Roswell Report: Fact vs. Fiction in the New Mexico Desert supported this with extensive documentation that narrowed the cause of the debris to a specific Mogul balloon train launched on June 4, 1947, and lost near the Roswell debris field.[128] Within the UFO community, the reports were not accepted.[129] UFO researchers dismissed the reports as containing no information about MJ-12 or extraterrestrial corpses but noted the reports did admit the 1947 account to have been false.[130] Contemporary polls found the majority of Americans doubted the Air Force explanation.[131][132]

News media and skeptical researchers embraced the findings.[133] Project Mogul offered a cohesive explanation for the contemporary accounts of the debris – failing only to explain later conflicting additions.[134] Carl Sagan and Phil Klass noted that the symbols from the 1947 debris – described by Jesse Marcel Jr. as alien hieroglyphics – were easily explained as matching the symbols on the adhesive tape that Project Mogul sourced from a New York toy manufacturer.[135][136] In 1997, the Air Force released The Roswell Report: Case Closed. This final report detailed how eyewitness accounts of military personnel loading aliens into "body bags" matched the Air Force's procedures for retrieving parachute test dummies in insulation bags, designed to shield temperature-sensitive equipment in the desert.[137]

Later theories and hoaxes (1994–present)

Alien Autopsy

Pseudo-documentaries, most notably Alien Autopsy: Fact or Fiction, have taken a major role in shaping popular opinion of Roswell.[140] In 1995, British entrepreneur Ray Santilli claimed to have footage of an alien autopsy filmed after the 1947 Roswell crash, purchased from an elderly Army Air Force cameraman.[141][142] Alien Autopsy centers around Santilli's hoaxed footage, which it presents as a probable artifact of the government's investigation into Roswell.[143][144] The purported cameraman Barnett had died in 1967 without ever serving in the military,[145] and visual effects expert Stan Winston told newspapers that Alien Autopsy had misrepresented his conclusion that Santilli's footage was an obvious fake.[138] Santilli would admit years later that the footage was fabricated.[146]

Over twenty million viewers watched the purported autopsy.[75] Fox aired the program immediately before and implicitly connected to the fictional X-Files, which later parodied the film.[139][147] Alien Autopsy established a template for future pseudo-documentaries built on questioning a presumed government cover-up.[140] Though thoroughly debunked, core UFO believers, many of whom still accepted earlier hoaxes like the Aztec crash,[148] weighed the autopsy footage as additional evidence strengthening the connection between Roswell and extraterrestrials.[149]

The Day After Roswell

In 1997, retired Army Intelligence officer Philip J. Corso released The Day After Roswell before the incident's 50th anniversary.[150] Corso's book combined many existing and conflicting conspiracies, with his own claim that a master sergeant showed him a purportedly-nonhuman body suspended in liquid inside a glass coffin.[151][152] The Day After Roswell contains many factual errors and inconsistencies.[153] For example, Corso says the 1947 debris was "shipped to Fort Bliss, Texas, headquarters of the 8th Army Air Force".[154] All other Roswell books correctly located the 8th Army Air Force headquarters at Fort Worth Army Air Field, 500 miles away.[155]

Corso further claimed that he helped oversee a project to reverse engineer recovered crash debris.[156] Other ufologists expressed doubts about Corso's book.[157] Don Schmitt openly questioned if Corso was "part of the disinformation" Schmitt believed was working to discredit ufology.[158] Corso's story was criticized for its similarities to science fiction like The X-Files and the film "Terminator 2".[159] Lacking evidence, the book relied on weight provided by Corso's past work on the Foreign Technology Division, and a foreword from U.S. Senator and World War II veteran Strom Thurmond.[160] Corso had misled Thurmond to believe he was providing a foreword for a different book. Upon discovering the book's actual contents, Thurmond demanded the publisher remove his name and writing from future printings stating, "I did not, and would not, pen the foreword to a book about, or containing, a suggestion that the success of the United States in the Cold War is attributable to the technology found on a crashed UFO."[161][162]

Related debunked or fringe theories

Roswell has remained the subject of divergent popular works, including those by ufologist Walter Bosley, paranormal author Nick Redfern, and American journalist Annie Jacobsen.[163] In 2011, Jacobsen's Area 51: An Uncensored History of America's Top Secret Military Base featured a claim that Nazi doctor Josef Mengele was recruited by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin to produce "grotesque, child-size aviators" to cause hysteria.[164] The book was criticized for extensive errors by scientists from the Federation of American Scientists.[165] Historian Richard Rhodes, writing in The Washington Post, also criticized the book's sensationalistic reporting of "old news" and its "error-ridden" reporting. He wrote: "All of [her main source's] claims appear in one or another of the various publicly available Roswell/UFO/Area 51 books and documents churned out by believers, charlatans and scholars over the past 60 years. In attributing the stories she reports to an unnamed engineer and Manhattan Project veteran while seemingly failing to conduct even minimal research into the man's sources, Jacobsen shows herself at a minimum extraordinarily gullible or journalistically incompetent."[166]

The 2013 documentary Mirage Men suggests there was conspiracy by the U.S. military to fabricate UFO folklore in order to deflect attention from classified military projects.[167] The book it is based on, also called Mirage Men, was published in 2010 by Constable & Robinson.[168]

In September 2017, UK newspaper The Guardian reported on Kodachrome slides which some had claimed showed a dead space alien.[169] First presented at a BeWitness event in Mexico, organised by Jaime Maussan and attended by almost 7,000 people, days afterwards it was revealed that the slides were in fact of a mummified Native American child discovered in 1896 and which had been on display at the Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum in Mesa Verde, Colorado, for many decades.[169]

In February 2020, an Air Force historian revealed a recently declassified report of a circa-1951 incident in which two Roswell personnel donned poorly fitting radioactive suits, complete with oxygen masks, while retrieving a weather balloon after an atomic test. On one occasion, they encountered a lone woman in the desert, who fainted when she saw them. One of the personnel suggests they could have appeared to someone unaccustomed to then-modern gear, to be alien.[170][171]

Modern views

Secrecy around the initial incident was due to Cold War military programs rather than aliens.[172] Contrary to evidence, UFO believers maintain that a spacecraft crashed near Roswell,[173] and "Roswell" remains synonymous with UFOs.[174] B. D. Gildenberg has called the Roswell incident "the world's most famous, most exhaustively investigated, and most thoroughly debunked UFO claim".[175] Accounts of alien recovery sites are contradictory and not present in any 1947 reports.[176] Some accounts are likely distorted memories of recoveries of servicemen in plane crashes, or parachute test dummies, as suggested by the Air Force in their 1997 report.[177] Karl Pflock argues that proponents of the crashed-saucer explanation tend to overlook contradictions and absurdities, compiling supporting elements without adequate scrutiny.[178] Kal Korff attributes the poor research standards to financial incentives, "Let's not pull any punches here: The Roswell UFO myth has been very good business for UFO groups, publishers, for Hollywood, the town of Roswell, the media, and UFOlogy ... [The] number of researchers who employ science and its disciplined methodology is appallingly small."[179]

Project Mogul

A 1994 USAF report identified the crashed object from the 1947 incident as a Project Mogul device.[1] Mogul – the classified portion of an unclassified New York University atmospheric research project – was a military surveillance program employing high-altitude balloons to monitor nuclear tests.[180] The project launched Flight No. 4 from Alamogordo Army Air Field on June 4. Flight No. 4 was drifting toward Corona within 17 miles of Brazel's ranch when its tracking equipment failed.[126] The military, charged with protecting the classified project, claimed that the crash was of a weather balloon.[76][181] Major Jesse Marcel and USAF Brigadier General Thomas DuBose publicly described the claims of a weather balloon as a cover story in 1978 and 1991, respectively.[72] In the USAF report, Richard Weaver states that the weather balloon story may have been intended to "deflect interest from" Mogul, or it may have been the perception of the weather officer because Mogul balloons were constructed from the same materials.[182] Sheridan W. Cavitt, who accompanied Marcel to the debris field, provided a sworn witness statement for the report.[183] Cavitt stated, "I thought at the time and think so now, that this debris was from a crashed balloon."[184]

Ufologists had previously considered the possibility that the Roswell debris had come from a top-secret balloon. In March 1990, John Keel proposed that the debris had been from a Japanese balloon bomb launched in World War 2.[185][186] An Air Force meteorologist rejected Keel's theory, explaining that the Fu-Go balloons "could not possibly have stayed aloft for two years".[187] Project Mogul, an American balloon program inspired by the Japanese balloons, first connected to Roswell by independent researcher Robert G. Todd first in 1990.[188][189] Todd contacted ufologists and in the 1994 book Roswell in Perspective, Karl Pflock agreed that the Brazel ranch debris was from Mogul.[188][190] In response to a 1993 inquiry from US congressman Steven Schiff of New Mexico,[191] the General Accounting Office launched an inquiry and directed the Office of the United States Secretary of the Air Force to conduct an internal investigation.[126] Air Force declassification officer Lieutenant James McAndrew concluded:

When the civilians and personnel from Roswell AAF [...] 'stumbled' upon the highly classified project and collected the debris, no one at Roswell had a 'need to know' about information concerning MOGUL. This fact, along with the initial mis-identification and subsequent rumors that the 'capture' of a 'flying disc' occurred, ultimately left many people with unanswered questions that have endured to this day.[192]

'Alien bodies' as later hoaxes or test dummies

The Air Force concluded that reports of recovered alien bodies were likely a combination of innocently transformed memories of accidents involving military casualties with memories of the recovery of anthropomorphic dummies in military programs such as the 1950s Operation High Dive. Recollection of these test dummies could be mixed with a myriad of hoaxes or misconceptions. Project Mogul did not involve test dummies but U.S. Air Force high altitude balloons did drop test dummies from high altitudes and they both operated in the New Mexico Desert.[177]

Critics suggest claims of alien bodies face credibility problems with witnesses making contradictory accounts. Death-bed confessions or accounts from elderly and easily confused witnesses to one party are also considered problematic.[194][195][196] Pflock noted that only four people with supposed firsthand knowledge of alien bodies were interviewed by Roswell authors.[197] Additionally reports of bodies came about 40 years after the fact.[176]

Roswell as modern myth and folklore

The mythology of Roswell involving increasingly elaborate accounts of alien crash landings and government cover-ups has been analyzed and documented by social anthropologists and skeptics.[198] Anthropologists Susan Harding and Kathleen Stewart highlight the Roswell Story was a prime example of how a discourse moved from the fringes to the mainstream, aligning with the 1980s zeitgeist of public fascination with "conspiracy, cover-up and repression".[35] Skeptics Joe Nickell and James McGaha proposed that Roswell's time spent away from public attention allowed the development of a mythology drawing from later UFO folklore, and that the early debunking of the incident created space for ufologists to intentionally distort accounts towards sensationalism.[199]

Charles Ziegler argues that the Roswell story exhibits characteristics typical of traditional folk narratives. He identifies six distinct narratives and a process of transmission through storytellers, wherein a core story was formed from various witness accounts and then shaped and altered by those involved in the UFO community. Additional "witnesses" were sought to expand upon the core narrative, while accounts that did not align with the prevailing beliefs were discredited or excluded by the "gatekeepers".[200][201]

Statements by US Presidents

In a 2012 visit to Roswell, Barack Obama joked "I come in peace."[202] When asked during a 2015 interview with GQ magazine about whether he had looked at top-secret classified information, Obama replied, "I gotta tell you, it's a little disappointing. People always ask me about Roswell and the aliens and UFOs, and it turns out the stuff going on that's top secret isn't nearly as exciting as you expect. In this day and age, it's not as top secret as you'd think."[203] In December 2020, Obama joked with Stephen Colbert: "It used to be that UFOs and Roswell was the biggest conspiracy. And now that seems so tame, the idea that the government might have an alien spaceship."[204]

In a 2014 interview, Bill Clinton said that his administration had investigated the incident, saying "When the Roswell thing came up, I knew we'd get gazillions of letters. So I had all the Roswell papers reviewed, everything".[205]

In June 2020, Donald Trump, when asked if he would consider releasing more information about the Roswell incident, said "I won't talk to you about what I know about it, but it's very interesting."[206]

Cultural impact

Tourism & commercialization

.jpg.webp)

Roswell's tourism industry is based on ufology museums and businesses, as well as alien-themed iconography and alien kitsch.[207] A yearly UFO festival has been held since 1995.[208] There are several alleged crash sites that can be visited for a fee, as well as alien museums, festivals and conventions, including the International UFO Museum and Research Center, founded in 1991.[209]

Popular fiction

In the 1980 independently distributed film Hangar 18, an alien ship crashes in the desert of the US Southwest. Debris and bodies are recovered, but their existence is covered up by the government.[53] Director James L. Conway summarized the film as "a modern-day dramatization of the Roswell incident".[53] Conway later revisited the concept in 1995 when he filmed the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode "Little Green Men"; In that episode, characters travel to 1947, triggering the Roswell incident, with their ship being stored in Hangar 18.[210][211]

Beginning in 1993, the hit television series The X-Files featured the Roswell incident as a recurring element. The show's second episode "Deep Throat", introduced a Roswell alien crash into the show's mythology. The comical 1996 episode "Jose Chung's From Outer Space" satirized the recently-broadcast Santelli Alien Autopsy hoax film.[212] After the success of The X-Files, Roswell alien conspiracies were featured in other sci-fi drama series, including Dark Skies (1996–97) and Taken (2002).[213][214][215]

In 1994 a film titled Roswell, based on the book UFO Crash at Roswell, by Kevin D. Randle and Donald R. Schmitt was released.[216]

In the 1996 film Independence Day, an alien invasion prompts the revelation of a Roswell crash and cover-up extending even to concealing the information from the President of the United States, to facilitate plausible deniability, according to the Defense Secretary.[217][218] The 2008 film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull sees the protagonist on a quest for an alien body from the Roswell Incident.[219]

In a 2001 episode of the animated comedy Futurama, titled, "Roswell That Ends Well", protagonists from the 31st century travel back in time and cause the Roswell incident.[220] The 2006 comedy Alien Autopsy revolves around the 1990s-creation of the Santilli hoax film.[221] The 2011 Simon Pegg comedy Paul tells the story of Roswell tourists who rescue a grey alien.[222] Starting in 1998, Pocket Books published a series of young adult novels titled Roswell High; From 1999 to 2002, the books were adapted into the WB/UPN TV series Roswell,[223] with a second adaption release in 2019 under the title Roswell, New Mexico.[224]

See also

References

- 1 2 The Roswell material has been attributed to a top secret military balloon by astrophysicist Adam Frank, historian Lt Col James Michael Young, science writer Kendrick Frazier, folklorist Thomas Bullard, historian Kathryn Olmsted, Project Mogul meteorologist B.D. Gildenberg, journalist Kal Korff, skeptical UFO researcher Philip J. Klass, and intelligence officer Captain James McAndrew among others:

- Frank 2023, p. 551: "The weather-balloon story was indeed a lie. Instead, what crashed on Brazel's ranch was Project Mogul, a secret experimental program using high-altitude balloons to monitor Russian nuclear tests.

- Young 2020, p. 27: "[L]aunch #4 on June 4, 1947, captured the public's attention when a local rancher recovered the balloon debris. Noting unusual metallic objects attached to the debris and suspecting they belonged to the military, the rancher turned the material and objects over to officers at Roswell Army Airfield (RAAF)."

- Frazier 2017a: "[...] what we now know the debris to have been: remnants of a long train of research balloons and equipment launched by New York University atmospheric researchers [...]"

- Bullard 2016, p. 80: "the Air Force [...] concluded that the wreckage belonged to a Project Mogul balloon array that had disappeared in June 1947."

- Olmsted 2009, p. 184: "When one of these balloons smashed into the sands of the New Mexico ranch, the military decided to hide the project's real purpose."

- Gildenberg 2003, p. 62: "One such flight, launched in early June, came down on a Roswell area sheep ranch, and created one of the most enduring mysteries of the century."

- Korff 1997, fig. 7: "Unbeknownst to Major Marcel, the debris was actually the remnants of a highly classified military spy device known as Project Mogul."

- Klass 1997a, fig. 3: "[...] the debris was from a 600-foot long string of twenty-three weather balloons and three radar targets that had been launched from Alamogordo Army Air Field as part of a 'Top Secret' Project Mogul [...]"

- McAndrew 1997, p. 16: "The 1994 Air Force report determined that project Mogul was responsible for the 1947 events. Mogul was an experimental attempt to acoustically detect suspected Soviet nuclear weapon explosions and ballistic missile launches."

- ↑ Goldberg 2001, pp. 214–215

- 1 2 Olmsted 2009, p. 183

- 1 2 Olmsted 2009, p. 184

- ↑ Frazier 2017a: "Flight 4 was launched June 4, 1947, from Alamogordo Army Air Field and tracked flying northeast toward Corona. It was within 17 mi [27 km] of the Brazel ranch when contact was lost."

- 1 2 3 Goldberg 2001, pp. 192–193

- 1 2 3 "New Mexico Rancher's 'Flying Disk' Proves to Be Weather Balloon-Kite". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Fort Worth, TX. July 9, 1947. pp. 1, 4.

- ↑ Kottmeyer 2017, p. 172

- ↑ Frank 2023, p. 510

- ↑ Peebles 1994, p. 246

- ↑ Klass 1997b, pp. 35–36, 21

- ↑ Clarke 2015, pp. 36–37

- ↑ Pflock 2001, p. 29

- ↑ Weaver & McAndrew 1995, p. 23: "I was a member of the crew which flew parts of what we were told was a flying saucer to Fort Worth. [...] I was involved in loading the B-29 with the material, which was wrapped in packages with wrapping paper. One of the pieces was triangle-shaped, about 2 1/2 feet across the bottom. The rest were in small packages, about the size of a shoe box, The brown paper was held with tape. The material was extremely lightweight. When I picked it up, it was just like picking up an empty package. [...] All of the packages could have fit into the trunk of a car [...] When we came back from lunch, they told us they had transferred the material to a B-25. They told us the material was a weather balloon, but I'm certain it wasn't a weather balloon,"

- ↑ Pflock 2001, p. 27

- ↑ "Flying Disc Found; In Army Possession". The Bakersfield Californian. Bakersfield, California. Associated Press. July 8, 1947. p. 1.

- 1 2 Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, p. 9

- ↑ "AAF Whips Up a Disc Flurry". The Journal Herald. July 9, 1947. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 "Harassed Rancher who Located 'Saucer' Sorry He Told About it". Roswell Daily Record. July 9, 1947.

The balloon which held it up, if that was how it worked, must have been 12 feet [3.5 m] long, [Brazel] felt, measuring the distance by the size of the room in which he sat. The rubber was smoky gray in color and scattered over an area about 200 yards [180 m] in diameter. When the debris was gathered up, the tinfoil, paper, tape, and sticks made a bundle about three feet [1 m] long and 7 or 8 inches [18 or 20 cm] thick, while the rubber made a bundle about 18 or 20 inches [45 or 50 cm] long and about 8 inches [20 cm] thick. In all, he estimated, the entire lot would have weighed maybe five pounds [2 kg]. There was no sign of any metal in the area which might have been used for an engine, and no sign of any propellers of any kind, although at least one paper fin had been glued onto some of the tinfoil. There were no words to be found anywhere on the instrument, although there were letters on some of the parts. Considerable Scotch tape and some tape with flowers printed upon it had been used in the construction. No strings or wires were to be found but there were some eyelets in the paper to indicate that some sort of attachment may have been used.

Cited in McAndrew 1997, p. 8. - ↑ Korff 1997, p. 159

- ↑ Klass 1997b, p. 20

- ↑ Kloor 2019, p. 21

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, p. 12

- 1 2 ABC News 2005, p. 1

- ↑ Goldberg 2001, p. 193

- ↑ Wright 1998, p. 39

- ↑ Weeks 2015, ch. 17

- ↑ "Twin Falls Falling Disc Proves Ingenious Hoax of 4 Teen-age Boys". Deseret News. July 12, 1947. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Peebles 1994, pp. 33, 251

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Peebles 1994, p. 251

- ↑ Peebles 1994, p. 245

- ↑ Goldberg 2001, pp. 208, 253–255

- ↑ Olmsted 2009, pp. 173, 184

- 1 2 Harding & Stewart 2003, p. 273

- 1 2 3 4 Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 13–14

- 1 2 Clarke 2015, ch. 13: "It appeared the Aztec story was destined to join the Aurora airship crash and the Roswell weather balloon as a flash in the ufological pan, quickly to be forgotten. In hindsight all three provided the basic template for what became the modern crashed saucer legend."

- ↑ Peebles 1994, pp. 48–50, 251

- 1 2 Peebles 1994, pp. 242, 251

- ↑ Smith 2000, p. 88

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 14, 36, 42

- ↑ Dickey, Colin (September 11, 2023). "They Knew What They Had Seen". Slate.

- ↑ Levy & Mendlesohn 2019, p. 136: "However, it is the Betty and Barney Hill abduction account that brings the grays fully into public consciousness [...] As knowledge of the Hills’ experiences spread, so too did sightings of grays. This included the addition of grays to popularized accounts of the 1947 Roswell UFO incident."

- ↑ McAndrew 1997, pp. 84–85

- ↑ Nickell & McGaha 2012, p. 33

- ↑ Fuller 1966, pp. 87–88: "There have been, I learned after I started this research, frequent and continual rumors (and they are only rumors) that in a morgue at Wright-Patterson Field, Dayton, Ohio, lie the bodies of a half-dozen or so small humanoid corpses, measuring not more than four-and-a-half feet in height, evidence of one of the few times an extraterrestrial spaceship has allowed itself either to fail or otherwise fall into the clutches of the semicivilized Earth People."

- 1 2 3 Smith 2000, p. 82

- ↑ Peebles 1994, p. 242

- ↑ Peebles 1994, p. 244: " Stringfield described the evidence Carr had collected on the Aztec 'crash.' Carr said he had found five eyewitnesses to the recovery. One (now dead) was a surgical nurse at the alien's autopsy. Another was a high-ranking Air Force officer."

- ↑ Disch 2000, pp. 53–34: "Even the Roswell case [...] has its component of science-fictional fraud. Robert Spencer Carr became famous, briefly, in the '70s when, in a radio interview, he concocted the still-current story of aliens' autopsied and kept in cold storage at the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, near Dayton, Ohio. Carr."

- ↑ "Air Force Freezes Ufo Story". Ann Arbor Sun. Zodiac News Service. November 1, 1974 – via Ann Arbor District Library.

- ↑ Jones, Jack (October 12, 1974). "No Green Men Here, Base Officials Say". Dayton Daily News. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Erdmann & Block 2000, p. 287

- ↑ Bullard 2016, p. 331

- ↑ Carr, Timothy (July 1997). "Son of Originator of 'Alien Autopsy' Story Casts Doubt on Father's Credibility" (PDF). Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 21, no. 4. p. 31.

- ↑ Smith 2000, p. 92

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 16–17

- ↑ Frank 2023, pp. 520–529

- ↑ Klass 1997b, p. 67

- ↑ Pflock 2001, p. 225

- ↑ Pratt, Bob (February 26, 1980). "Former Intelligence Officer Reveals...I Picked Up Wreckage of UFO That Exploded Over US". National Enquirer. p. 8.

- ↑ "UFO Coverup". In Search Of... Season 5. Episode 1. September 20, 1980.

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 16–17, 21, 22, 23, 24–25, 39–40, 46, 62

- ↑ Klass 1997b, pp. 9–10

- ↑ Klass 1997b, pp. 186, 198

- ↑ "Roswell author who said he handled UFO crash debris dies at 76". The Guardian. Associated Press. August 8, 2013. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ↑ Korff 1997, p. 26

- ↑ Korff, Kal (August 1997). "What Really Happened at Roswell". Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 21, no. 4. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ↑ Items from the diagram as cited in text:

- Fu-Go Balloons: Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 7, 44, 76, 181

- Project Mogul Balloons: Young 2020, pp. 25, 27, 29

- Kenneth Arnold: May 2016, p. 62

- Twin Falls Recovered Disc Hoax: Wright 1998, p. 39

- Aztec Hoax Bodies: Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 13–14

- Jesse Marcel: Gildenberg 2003, p. 65

- San Augustin Bodies: Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 16–17, 21, 22, 23, 24–25, 39–40, 46, 62

- Roswell Bodies: Smith 2000, p. 7

- Roswell Alien Autopsy: Smith 2000, pp. 73, 127

- Thomas DuBose: Pflock 2001, pp. 33

- USAF Report: Frazier 2017b

- 1 2 Smith 2000, p. 7

- ↑ Smith 2000, pp. 73, 127

- 1 2 3 Pflock 2001, pp. 33

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 4, 12, 26–27, 28, 177

- ↑ ABC News 2005, p. 3

- 1 2 ABC News 2005, p. 2

- 1 2 3 Olmsted 2009, p. 184: "When one of these balloons smashed into the sands of the New Mexico ranch, the military decided to hide the project's real purpose."

- ↑ Frank 2023, p. 529

- ↑ Berlitz & Moore 1980, p. 28

- ↑ Berlitz & Moore 1980, p. 79

- ↑ Berlitz & Moore 1980, p. 83

- ↑ Berlitz & Moore 1980, pp. 88–89

- 1 2 Goldberg 2001, p. 197

- ↑ Berlitz & Moore 1980, p. 33

- ↑ Berlitz & Moore 1980, pp. 67–69

- ↑ Berlitz & Moore 1980, p. 42

- ↑ Korff 1997, p. 29

- ↑ Berlitz & Moore 1980, pp. 75, 88

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 44–45

- ↑ Randle & Schmitt 1994, pp. 115, 121, cited in: Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, p. 44

- ↑ Klass 1997b, pp. 25, 35, 84, 66

- ↑ Pflock 2001, pp. 82

- ↑ Goldberg 2001, p. 196

- ↑ Rodeghier & Whiting 1992, p. 2

- ↑ Klass, Philip J. (1990). "New Evidence of MJ-12 Hoax" (PDF). Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 14. pp. 135–140.

- ↑ Friedman 2005

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 19–20

- ↑ Donovan 2011, pp. 104–105

- ↑ Korff 1997, pp. 197–207

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, p. 21

- ↑ McAndrew 1997, p. 75

- ↑ Pflock 2001, pp. 51

- ↑ "Legend: Roswell Crash and Area 51". Unsolved Mysteries. Season 6. Episode 33. September 18, 1994. NBC – via FilmRise True Crime.

- ↑ Rich, Alan (July 29, 1994). "Roswell". Variety. Penske Media.

- ↑ Pflock 2001, p. 134

- ↑ Klass 1997b, p. 192

- ↑ Pflock 2001, pp. 127

- ↑ Dunning, Brian (December 18, 2007). "Aliens in Roswell". Skeptoid. Retrieved October 9, 2016.

- ↑ Klass 1997a, p. 5

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 20

- ↑ Randle & Schmitt 1991, p. 200

- ↑ Pflock 2001, pp. 36

- 1 2 3 4 Goldberg 2001, p. 199

- ↑ Pflock 2001, p. 91

- ↑ "Albuquerque Journal". October 27, 1991. p. 84 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Pflock 2001, p. 34

- ↑ Randle & Schmitt 1991, p. 206

- ↑ Pflock 2001, pp. 176–177

- ↑ Friedman & Berliner 1997

- 1 2 Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 21–22

- ↑ Goldberg 2001, p. 192

- ↑ Korff 1997, pp. 33–35

- 1 2 Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 24–25

- ↑ Goldberg 2001, pp. 214, 227–228

- ↑ Kloor 2019, p. 52

- 1 2 3 Frazier 2017b

- ↑ "Report of Air Force Research Regarding the 'Roswell Incident'" (PDF) (Report). U.S. Air Force. July 1994.

- ↑ Clarke 2015, ch. 6 par. 13.16

- ↑ Clarke 2015, ch. 6 par. 13.17

- ↑ Goldberg 2001, pp. 214–215

- ↑ ABC News 2005, p. 3

- ↑ Goldberg 2001, p. 225

- ↑ Goldberg 2001, pp. 214–215

- ↑ Pflock 2001, pp. 152–155

- ↑ Klass 1997b, pp. 118–119

- ↑ Sagan 1997, p. 82

- ↑ Broad 1997, p. A3

- 1 2 Levy & Mendlesohn 2019, p. 32

- 1 2 Lavery, Hague & Cartwright 1996, p. 17

- 1 2 Goldberg 2001, p. 219

- ↑ Korff 1997, p. 204

- ↑ Pflock 2001, p. 201

- ↑ Frank 2023, p. 1101

- ↑ Korff 1997, pp. 212–213

- ↑ Korff 1997, p. 213

- ↑ Frank 2023, p. 1109

- ↑ Knight 2013, p. 50

- ↑ Frank 2023, p. 1117

- ↑ Ricketts 2011, p. 250

- ↑ Clarke 2015, ch. 6 paras.&nsbp;13.13–13.15

- ↑ Pflock 2001, p. 204

- ↑ Corso & Birnes 1997, pp. 27, 32–34

- ↑ Klass 1998, pp. 1–5

- ↑ Klass 1998, p. 1

- ↑ Klass 1998, pp. 1

- ↑ Klass 1998, pp. 1–5

- ↑ Smith 2000, p. 56

- ↑ Goldberg 2001, p. 227

- ↑ Clarke 2015, ch. 6 para.&nsbp;13.13: " If Corso’s story sounded like the product of watching too much science fiction then perhaps it was. In the second episode of The X-Files, originally shown in September 1994, FBI agents Fox Mulder and Dana Scully discuss the mysterious disappearance of a test pilot during a flap of UFO sightings near a secret airbase. The sceptical Scully asks Mulder 'Are you suggesting that the military are flying UFOs?' Mulder replies: ‘No. Planes built using UFO technology.'"

- ↑ Pflock 2001, pp. 204, 207

- ↑ Gerhart, Ann; Groer, Ann (June 6, 1997). "The Reliable Source". Washington Post.

- ↑ Pflock 2001, pp. 207–208

- ↑ Gulyas 2014, ch. 9, paras. 34-50.

- ↑ Harding, Thomas (May 13, 2011). "Roswell 'was Soviet plot to create US panic'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on May 20, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ↑ Norris, Robert; Richelson, Jeffrey (July 11, 2011). "Dreamland Fantasies". Washington Decoded. Archived from the original on March 5, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ↑ Rhodes, Richard (June 3, 2011). "Annie Jacobsen's "Area 51," the U.S. top-secret military base". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 10, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ↑ Dalton, Stephen (June 13, 2013). "Mirage Men: Film Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ↑ Pilkington, Mark (2010). Mirage men: a journey in disinformation, paranoia and UFOs. London: Constable. ISBN 978-1-84529-857-9.

- 1 2 Carpenter, Les (September 30, 2017). "The curious case of the alien in the photo and the mystery that took years to solve". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ↑ Neale, Rick (February 8, 2020). "Stranger things?". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 1A, 8A, 9A. Archived from the original on February 8, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ↑ Young 2020, p. 27

- ↑ Frank 2023, p. 622

- ↑ Kloor 2019, p. 52

- ↑ Joseph 2008, p. 132

- ↑ Gildenberg 2003, p. 73

- 1 2 Gildenberg 2003, pp. 64, 70

- 1 2 Broad 1997, p. 18

- ↑ Pflock 2001, p. 223

- ↑ Korff 1997, p. 248

- ↑ Frazier 2017a

- ↑ Weaver & McAndrew 1995, p. 9: "... the material recovered near Roswell was consistent with a balloon device and most likely from one of the MOGUL balloons that had not been previously recovered."

- ↑ Weaver & McAndrew 1995, pp. 27–30

- ↑ Gildenberg 2003, pp. 62–72

- ↑ Weaver & McAndrew 1995, p. 160

- ↑ Gulyas 2016: "Numerous explanations have arisen, ranging from Japanese 'Fugo' balloons [...]"

- ↑ Gulyas 2014: "[...] from John Keel, who advocated a solution to the Roswell question which credited Japanese Fugo balloons as the 'mysterious craft,' to Nick Redfern, whose Body Snatchers in the Desert [...]".

- ↑ Huyghe 2001, p. 133: "Edward Doty, a meteorologist who established the Air Force's Balloon Branch at nearby Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico beginning in 1948, calls the Japanese Fu-Go balloons 'a very fine technical job with limited resources.' But 'no way could one of these balloons explain the Roswell episode,' says Doty,'because they could not possibly have stayed aloft for two years.'"

- 1 2 Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, p. 27

- ↑ Weaver & McAndrew 1995, p. 167: "The Army Air Force had seen what the Japanese had done with long range balloons; although not effective as weapons, they did initiate the long-range balloon research which led to use of balloons for the detection and collection of debris from atomic explosion."

- ↑ Weaver & McAndrew 1995, p. 28: "Most interestingly, as this report was being written, Pflock published his own report of this matter under the auspices of FUFOR, entitled Roswell in Perspective (1994). Pflock concluded from his research that the Brazel Ranch debris originally reported as a "flying disc" was probably debris from a MOGUL balloon"

- ↑ "Los Angeles Times". January 30, 1994. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Weaver & McAndrew 1995, p. 316

- ↑ McAndrew 1997, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Korff 1997, pp. 77–81

- ↑ Korff 1997, pp. 86–104

- ↑ Korff 1997, pp. 107–108

- ↑ Pflock 2001, p. 118: "These are Frank Kaufmann, who also claimed to have seen a crash survivor; the late Jim Ragsdale; a Lt. Col. Albert Lovejoy Duran; and one Gerald Anderson, who, like Kaufmanno told not only of seeing bodies but also a survivor, this at a third alleged crash site on the Plains of San Agustin in Catron County, about two hundred miles west-northwest of Roswell."

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 1–198

- ↑ Nickell & McGaha 2012, pp. 31–33

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, p. 1

- ↑ Saler, Ziegler & Moore 1997, pp. 34–37

- ↑ Dwyer, Devin (March 22, 2012). "In Oil and UFO Country, Obama Says 'I Come in Peace'". ABC News. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ Simmons, Bill (November 17, 2015). "Bill Simmons Interviews President Obama, GQ's 2015 Man of the Year". GQ. Archived from the original on November 5, 2017. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ↑ Diaz, Eric (December 7, 2020). "President Obama Admits He Was Briefed on UFO Sightings". Nerdist. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ↑ Kopan, Tal (April 3, 2014). "Bill Clinton phones home on aliens". Politico. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ↑ Madhani, Aamer (June 19, 2020). "Trump says he's heard 'interesting' things about Roswell". Military Times. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ↑ Siegler, Kirk; Baker, Liz (June 5, 2021). "The Truth Is (Still) Out There In 'UFO Capital' Roswell, New Mexico". NPR. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ↑ Ricketts 2011, p. 253

- ↑ Smith 2000, p. 19

- ↑ "Catching Up With Director James L. Conway, Part 1". StarTrek.com. February 16, 2012.

- ↑ Handlen, Zach (January 17, 2013). "Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: "Little Green Men"/"The Sword Of Kahless"". TV Club. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ↑ Klaver 2012, p. 149

- ↑ Carey & Schmitt 2020, p. 184

- ↑ Gulyas 2016, p. 84

- ↑ Frost, Warwick; Laing, Jennifer (December 9, 2013). "Commemorative Events: Memory, Identities, Conflict". Routledge – via Google Books.

- ↑ Rich, Alan (July 29, 1994). "Roswell". Variety. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ↑ "Top 5 Roswell References in Movies and TV". Entertainment.ie. July 9, 2013. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ↑ "Albert Nimzicki: Two words, Mr. President: "Plausible deniability"". moviequotedb.com. Archived from the original on September 14, 2019. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ↑ LeMay, John (December 9, 2008). "Roswell". Arcadia Publishing – via Google Books.

- ↑ Handlen, Zach (May 28, 2015). "Futurama: "Roswell That Ends Well"/"Anthology Of Interest II"". TV Club. Archived from the original on November 4, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ↑ Lagerfield, Nathalie (June 24, 2016). "How an Alien Autopsy Hoax Captured the World's Imagination for a Decade". Time. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (March 16, 2011). "Phone home? Dude, I'm into texting". RogerEbert.com.

- ↑ Beeler 2010, pp. 219, 214,

- ↑ Cordero, Rosy (May 12, 2022). "The CW's 'Roswell, New Mexico' Canceled After Four Seasons".

Sources

- "Aliens Changed Roswell, Even Without Proof". ABC News. February 24, 2005. Archived from the original on March 6, 2005. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- Beeler, Stan (2010). "Roswell". In Lavery, David (ed.). The Essential Cult TV Reader. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2568-8.

- Berlitz, Charles; Moore, William (1980). The Roswell Incident. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 978-0448211992.

- Broad, William J. (June 24, 1997). "Air Force debunks Roswell UFO story". The Day, New London, CT. The New York Times News Service. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016 – via Google News.

- Bullard, Thomas E. (2016). The Myth and Mystery of UFOs. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2338-9.

- Carey, Thomas J.; Schmitt, Donald R. (2020). Roswell: The Ultimate Cold Case : Eyewitness Testimony and Evidence of Contact and the Cover-up. Newburyport, Massachusetts: Red Wheel/Weiser. ISBN 978-1632651709.

- Clarke, David (2015). How UFOs Conquered the World: The History of a Modern Myth. London: Aurum Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1781314722.

- Corso, Philip J.; Birnes, William J. (1997). The Day After Roswell. New York: Pocket Books. ISBN 0671004611.

- Disch, Thomas M. (July 5, 2000). The Dreams Our Stuff is Made Of: How Science Fiction Conquered the World. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684859781.

- Donovan, Barna William (2011). Conspiracy Films: A Tour of Dark Places in the American Conscious. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0786486151.

- Erdmann, Terry J.; Block, Paula M. (2000). Deep Space Nine Companion. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0671501068.

- Frank, Adam (2023). The Little Book of Aliens (Ebook ed.). New York: Harper. ISBN 9780063279773.

- Frazier, Kendrick (July 16, 2017a). "Roswell myth lives on despite the established facts". Albuquerque Journal. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- Frazier, Kendrick (2017b). "The Roswell Incident at 70: Facts, Not Myths". Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 41, no. 6. pp. 12–15. Archived from the original on July 20, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- Friedman, Stanton; Berliner, Don (1997) [Originally published 1992]. Crash at Corona: The U.S. Military Retrieval and Cover-Up of a UFO (Paperback ed.). New York: Marlowe & Co. ISBN 1-56924-863-X.

- Friedman, Stanton (2005). Top Secret/MAJIC : Operation Majestic-12 and the United States Government's UFO Cover-Up. New York: Marlowe & Co. ISBN 978-1569243428.

- Fuller, John G. (1966). Incident at Exeter. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 712083.

- Gildenberg, B.D. (Spring 2003). "A Roswell Requiem". Skeptic. Vol. 10, no. 1 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- Goldberg, Robert Alan (2001). "Chapter 6: The Roswell Incident". Enemies Within: The Culture of Conspiracy in Modern America. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300132946.

- Gulyas, Aaron John (2014). The Chaos Conundrum: Essays on UFOs, Ghosts & Other High Strangeness in Our Non-Rational and Atemporal World. Luton, United Kingdom: Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 9780991697588.

- Gulyas, Aaron John (2016). Conspiracy Theories: The Roots, Themes and Propagation of Paranoid Political and Cultural Narratives. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 9781476623498.

- Harding, Susan; Stewart, Kathleen (2003). "Chapter 9: Anxieties of influence: Conspiracy Theory and Therapeutic Culture in Millennial America". In West, Harry G.; Sanders, Todd (eds.). Transparency and Conspiracy: Ethnographies of Suspicion in the New World Order. Duke University Press. ISBN 082238485X.

- Huyghe, Patrick (2001). "Chapter 24: Blaming the Japanese for Roswell". Swamp Gas Times: My Two Decades on the UFO Beat (Second ed.). New York: Paraview Press. ISBN 9781931044271.

- Joseph, Brad (2008). "Beyond the textbook: studying Roswell in the social studies classroom". Social Studies. 99 (3): 132–134. doi:10.3200/TSSS.99.3.132-134.

- Klass, Philip (January 1997a). "The Klass Files" (PDF). The Skeptics UFO Newsletter. Vol. 43. The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Archived from the original on April 19, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- Klass, Philip J. (1997b). The Real Roswell Crashed-Saucer Coverup. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-164-5.

- Klass, Philip (January 1998). "The Klass Files" (PDF). The Skeptics UFO Newsletter. Vol. 49. The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- Klaver, Elizabeth (2012). Sites of Autopsy in Contemporary Culture. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791483428.

- Knight, Peter (2013). Conspiracy Culture: From Kennedy to the X Files. Oxfordshire, England: Routledge. ISBN 9781135117313.

- Kloor, Keith (2019). "UFOs Won't Go Away". Issues in Science and Technology. 35 (3): 39–56. doi:10.2307/26949023.

- Korff, Kal (1997). The Roswell UFO Crash: What They Don't Want You to Know (First ed.). Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1573921275.

- Kottmeyer, Martin S. (2017). "Why Have UFOs Changed Speed Over the Years?". In Grossman, Wendy M.; French, Christopher C. (eds.). Why Statues Weep: The Best of the "Skeptic". Oxfordshire, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-1134962525.

- Lavery, David; Hague, Angela; Cartwright, Maria (1996). Deny All Knowledge: Reading the X-Files. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815627173.

- Levy, Michael M; Mendlesohn, Farah (2019). Aliens in Popular Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440838330.

- May, Andrew (2016). Pseudoscience and Science Fiction. Switzerland: Springer International. ISBN 9783319426051.

- McAndrew, James (1997). The Roswell Report: Case Closed (PDF). Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160490187.

- Nickell, Joe; McGaha, James (May–June 2012). "The Roswellian Syndrome: How Some UFO Myths Develop". Skeptical Inquirer. Vol. 36, no. 3. Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. Archived from the original on January 26, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- Olmsted, Kathryn S. (2009). "Chapter 6: Trust No One: Conspiracies and Conspiracy Theories from the 1970s to the 1990s". Real Enemies: Conspiracy Theories and American Democracy, World War I to 9/11. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199753956.

- Peebles, Curtis (1994). Watch the Skies!: A Chronicle of the Flying Saucer Myth. Washington, DC: The Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 1-56098-343-4.

- Pflock, Karl (2001). Roswell: Inconvenient Facts and the Will to Believe. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1573928946.

- Randle, Kevin; Schmitt, Donald (1991). UFO Crash at Roswell. New York: Avon Books. ISBN 978-0380761968.

- Randle, Kevin; Schmitt, Donald (1994). The truth about the UFO Crash at Roswell (Hardcover ed.). New York: M Evans. ISBN 0-87131-761-3.

- Ricketts, Jeremy R. (2011). "Land of (Re) Enchantment: Tourism and Sacred Space at Roswell and Chimayó, New Mexico". Journal of the Southwest. 53 (2): 239–261. JSTOR 41710086.

- Rodeghier, Mark; Whiting, Fred (June 1992). "Gerald Anderson, Barney Barnett, and the Archaeologists". The Plains of San Agustin Controversy, July 1947 (PDF) (Report). Center for UFO Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2023.

- Sagan, Carl (1997). The Demon-Haunted World (Paperback ed.). London: Headline. ISBN 0-7472-5156-8.

- Saler, Benson; Ziegler, Charles; Moore, Charles (1997). UFO Crash at Roswell: The Genesis of a Modern Myth. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1560987512.

- Smith, Toby (2000). Little Gray Men: Roswell and the Rise of a Popular Culture. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826321213.

- Weaver, Richard; McAndrew, James (1995). The Roswell Report: Fact Versus Fiction in the New Mexico Desert (PDF). United States Air Force. ISBN 016048023X. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- Weeks, Andy (2015). Forgotten Tales of Idaho. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 9781625852465.

- Wright, Susan (1998). UFO Headquarters: Investigations On Current Extraterrestrial Activity In Area 51. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312207816.

- Young, James Michael (2020). "The U.S. Air Force's Long Range Detection Program and Project MOGUL". Air Power History. 67 (4): 25–32.