Anglo-Nepalese War

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bhakti Thapa (yellow) leading Nepalese Gurkhali Army against British forces | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| a little more than 11,000[6] | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||

| History of Nepal |

|---|

|

|

|

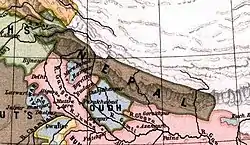

The Anglo-Nepalese War (1 November 1814 – 4 March 1816), also known as the Gorkha War, was fought between the Gorkhali army of the Kingdom of Nepal (present-day Nepal) and the British forces of the East India Company (EIC, present-day India). Both sides had ambitious expansion plans for the mountainous north of the Indian Subcontinent. The war ended with the signing of the Sugauli Treaty in 1816, which ceded some of the Nepalese-controlled territory to the EIC.

The British war effort was led by the East India Company and supported by a coalition of native states (the Garhwal Kingdom, the Patiala State and the Kingdom of Sikkim) against the Kingdom of Gorkha. Most of the Kingdom of Gorkha's war effort was led by the two Thapa families: the Thapa dynasty and the family of Amar Singh Thapa.[note 2]

Background

In the mid-eighteenth century, the British East India Company actively traded with Nepal.[13] Viewed as an opulence hub, Nepal supplied the Company with commodities such as rice, butter, oil seeds, timber, dyes, and gold.[13] In 1767, British concerns around this partnership grew when the Gorkhas ascended their power and leadership in Nepal.[13] In 1768, the Gorkhas conquered Kathmandu Valley and became Nepal’s ruling force, paving the way for a declining relationship between British India and Nepal.[13] In 1801, the Company established a British Residency in Kathmandu to seek a stronger hold over the region.[13] As 1814 approached, however, the British found themselves concerned by the possibility of an alliance between Nepal and Sikhs in northern India.[13] The Company believed that if Nepal was expelled from its Western lands, the “Terai” region, it would no longer pose a danger.[13] In 1814, this is what the British set out to do, alongside a goal of establishing a second Residency in Kathmandu to keep a close watch on the nation.[13] In May 1814, British forces in Nepal temporarily left to escape malaria season.[14] When Nepali forces aimed to reassert power, Company officials were killed in the process.[14] In 1814, Warren Hastings – Governor General of India – officially declared war on Nepal.[13] 16,000 troops were then sent to invade Nepal in September 1814.[14] The Treaty of Sagauli (1816) then marked the end of the Anglo-Nepalese War.[15]

The Shah era of Nepal began with the Gorkha King Prithvi Narayan Shah invading Kathmandu Valley, which consisted of the capital of the Malla confederacy. Until then, only the Kathmandu Valley had been referred to as Nepal. The confederacy requested help from the East India Company, and an ill-equipped and ill-prepared expedition, numbering 2,500, was led by Captain Kinlock in 1767. The expedition was a disaster, and the Gorkhali army easily overpowered those who had not succumbed to malaria or desperation. The ineffectual British force provided the Gorkhali with firearms and filled the Gorkhas with confidence, which possibly caused them to underestimate their opponents in future wars.

Victory and the occupation of the Kathmandu Valley by Prithvi Narayan Shah, starting with the Battle of Kirtipur, resulted in the shift of the capital of his kingdom from Gorkha to Kathmandu, and the empire that he and his descendants built then came to be known as Nepal. Also, the invasion of the wealthy Kathmandu Valley provided the Gorkha army with economic support for furthering their martial ambitions throughout the region.

To the north, however, aggressive raids into Tibet over a long-standing dispute over trade and control of the mountain passes triggered Chinese intervention. In 1792, the Chinese Qianlong Emperor sent an army that expelled the Nepalese from Tibet to within 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) of their capital, Kathmandu. Acting Regent Bahadur Shah (Prithvi Naryan's younger son) appealed to the British Governor-General of India for help. Anxious to avoid a confrontation with the Chinese, the Governor-General did not send troops but sent Captain Kirkpatrick as mediator. However, before he arrived the war with China had finished.

The Tibet affair had postponed a planned attack on the Garhwal Kingdom, but by 1803, the Raja of Garhwal, Pradyuman Shah, had also been defeated. He was killed in the struggle in January 1804, and all his land was annexed. Further west, general Amar Singh Thapa overran lands as far as Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, the strongest fort in the hill region, and laid siege to it. However, Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the ruler of the Sikh state in Punjab, intervened and had driven the Nepalese army east of the Sutlej River by 1809.

Causes

In the years leading up to the war, the British had been expanding their sphere of influence. While the Nepalese had been expanding their empire – into Sikkim to the east, the Kumaon and the Garhwal to the west, and into Awadh to the south – the British East India Company had consolidated its position in India from its main bases of Calcutta, Madras and Bombay. This British expansion had already been resisted in India, culminating in three Anglo-Maratha wars as well as in the Punjab where Ranjit Singh and the Sikh Empire had their own aspirations.

Territorial Conflict

Territorial conflict represents a significant cause of the Anglo-Nepalese War. First, Nepal’s views on borders and borderlands clashed with the Company’s visions of space and territoriality. Borderlands represent “zones of contact for the management, separation, and negotiation of difference,” and leading up to 1814, conflicts over borderlands played a pivotal role in spurring conflict between Nepal and British India.[16] Throughout its history, the Himalayas served as a site of political malleability and entangled agrarian entitlements.[16] As such, Nepal’s boundaries remained porous. As opposed to fixed territorial lines, Nepal possessed “an unbounded space” that facilitated heterogeneous movements of trade and people.[16] Nepal’s borders experienced frequent shifts in administration determined by the environment, tribute and taxation claims, and landholding patterns.[16] As a result, control over Anglo-Gorkha borderlands – Nepal’s frontiers with British India – oscillated frequently among different agents. In the eighteenth century, these borderlands became an area of deep concern for the British. The British viewed borders as fixed and immutable, leading the Company to interpret Nepal’s fluid boundaries as encroachments on British territory.[13]

Motivated by territorial concern, the Company embarked on surveys and mapmaking projects.[16] These activities involved carving political and administrative boundaries in Nepal to render the territory “more legible for colonial rule.”[16] These maps were then produced by the Revenue Surveys in the nineteenth century, serving as a strategy for the Company to divide land into non-overlapping, fixed spaces.[16] Clashing ideas around borderlands and spatiality, therefore, played an instrumental role leading up to the height of territorial disputes in 1814 – the onset of the Anglo-Nepalese War.[16]

Contents from the Treaty of Sagauli illustrate that clashes over territorial views aided in causing the war.[15] Article 2 states, “The Raja of Nepal renounces all claim to the lands which were the subject of discussion between the two States before the war, and acknowledges the right of the Honourable Company to the sovereignty of those lands.”[15] British forces’ focus on land and territoriality throughout the various articles of this Treaty exemplifies that territorial concern helped spur the war. Article 3 further states, “The Raja of Nepal hereby cedes to the Honourable the East India Company in perpetuity all the under-mentioned territories,” followed by the listing of five very detailed territorial spaces.[15] When describing one of these ceded lands, for example, the Treaty states, “hills eastward of the River Mitchee including the fort and lands of Nagree and the Pass of Nagarcote leading from Morung into the hills.”[15] These high levels of specificity, once again, showcase the Company’s highly fixed perceptions of borders and borderlands. As a result of the Anglo-Nepalese War and the subsequent treaty, Nepal lost approximately one-third of its land.[13] Disputes over territoriality, therefore, constituted a driving cause for war, following from the Company's deep concerns about Nepal’s fluid borders in the preceding years and decades.

The acquisition of the Nawab of Awadh's lands by the British East India Company brought the region of Gorakhpur into the close proximity of the raja(king) of Palpa – the last remaining independent town within the Nepalese heartlands. Palpa and Butwal were originally two separate principalities; they were afterwards united under one independent Rajput prince, who, having conquered Butwal, added it to his hereditary possessions of Palpa. The lands of Butwal, though conquered and annexed, were yet held in fief, or paid an annual sum, first to Awadh, and afterwards, by transfer, to the British.[17][18] During the regency of Rani Rajendra Laxmi, towards the close of the 18th century, the hill country of Palpa was conquered and annexed to Nepal. The rajah retreated to Butwal, but was subsequently induced, under false promises of redress, to visit Kathmandu, where he was put to death, and his territories in Butwal seized and occupied by the Nepalese.[18] Bhimsen Thapa, the Nepalese prime minister from 1806 to 1837, installed his own father as governor of Palpa, leading to serious border disputes between the two powers. The occupation of Terai of Butwal from 1804 till 1812 by the Nepalese, which was under British protection, was the immediate reason which led to the Anglo-Nepalese war in 1814.[18][19][20]

In October 1813, the ambitious Francis Edward Rawdon-Hastings, the Earl of Moira, assumed the office of the Governor-General, and his first act was to re-examine the border dispute between Nepal and British East India Company. These disputes arose because there was no fixed boundary separating the Nepalese and the British. A struggle with the former was unpromising as the British were ignorant of the country or its resources and, despite their technological superiority, it was a received persuasion that the nature of the mountainous tract, which they would have to penetrate, would be as baffling to them as it had been to all the efforts of many successive Mahomedan sovereigns.[21] A border commission imposed on Nepal by the Governor-General failed to solve the problem. The Nepalese Commissioners had remarked to the British the futility of debating about a few square miles of territory since there never could be real peace between the two States, until the British should yield to the Nepalese all the British provinces north of the Ganges, making that river the boundary between the two, "as heaven had evidently designed it to be."[21] However, Nepalese Historian Baburam Acharya contends that the British were striving to annex the hill regions of Nepal and were the ones responsible for creating border disputes. At the border demarcation, the British representative Major Bradshaw disrespected the Nepalese representatives – Rajguru Ranganath Poudyal and Kaji Dalabhanjan Pande, with a view of invoking a war against the Nepalese.[11] In the meantime, the British found that the Nepalese were preparing for war; that they had for some time been laying up large stores of saltpetre; purchasing and fabricating arms, and organizing and disciplining their troops under some European deserters in this service, after the model of the companies of East India's sepoy battalions.[17] The conviction that the Nepalese raids into the flatlands of the Terai, a much prized strip of fertile ground separating the Nepalese hill country from India, increased tensions[21] – the British felt their power in the region and their tenuous lines of communication between Calcutta and the northwest were under threat. Since there was no clear border, confrontation between the two powers was "necessary and unavoidable".[22] Britain formally declared war on Nepal on the 1st of November, 1814.[23]

Economic Interests

Economic interests also represent vital causes of the Anglo-Nepalese War. First, the British sought to utilize the trans-Himalayan trade routes through Kathmandu and eastern Nepal.[24] These routes would create access to untapped markets for British manufactured goods in Tibet and China.[24] In the late eighteenth century, therefore, the Company turned its attention toward trade between Tibet and British possessions in Bengal.[24] Under the leadership of Warren Hastings, trade missions were carried out to further these trade interests with the goal of establishing commercial relations with Nepal, Bhutan, and, ultimately, Tibet.[24] Tibet represented a source of Chinese silks, wool, dyestuffs, and other attractive commodities.[24] The Gorkha’s conquest of Kathmandu Valley and Nepal’s push into the Terai regions during the latter half of the eighteenth century, however, was viewed by the British as a threat to the Company’s trading plans.[24] British economic interests, therefore, played a major role in causing the Anglo-Nepalese War. The Treaty of Sagauli illustrates these economic interests, as seen by Britain ceding Nepali lands that covered these attractive trade routes.[15]

The British had made constant efforts to persuade the Nepalese government to allow them trade access to fabled Tibet through Nepal. Despite a series of delegations headed by William Kirkpatrick (1792), Maulvi Abdul Qader (1795), and later William O. Knox (1801), the Nepalese Durbar refused to budge an inch. The resistance to open up the country to the Europeans could be summed up in a Nepalese precept, "With the merchants come the musket and with the Bible comes the bayonet."

Lord Hastings was not averse to exploiting any commercial opportunities that access to the Himalayan region might offer. He knew that these would gratify his employers and silence his critics, because the East India Company was at this time in the throes of a cash-flow crisis. It needed substantial funds in Britain, in order to pay overheads, pensions, and dividends; but there were problems in remitting the necessary assets from India. Traditionally the company had bought Indian produce and sold it in London; but this no longer made economic sense. The staple Indian export was cotton goods, and demand for these was declining as home-produced textiles captured the British market. So the company was having to transfer its assets in another, more complicated and expensive way. It was having to ship its Indian textiles to Canton; sell them on the Chinese market; buy tea with the proceeds; then ship the tea for sale in Britain (all tea at this time came from China. It was not grown in India until the 1840s).[25][26]

So when Hastings told the directors of the Company about an alternative means of remittance, a rare and precious raw material that could easily and profitably be shipped from India directly to London, they were at once interested. The raw material in question was a superior-quality wool: the exquisitely soft and durable animal down that had been used since time immemorial to make the famous wraps, or shawls, of Kashmir. This down was found only on the shawl-wool goat, and the shawl-wool goat was found only in certain areas of western Tibet. It refused to breed anywhere else. This all explains why, under the terms of the treaty of 1816, Nepal was required to surrender its far western provinces. Hastings hoped that this territory, partly annexed by the company and partly restored to its previous rulers, would give British merchants direct access to the wool-growing areas.[25]

Similarly David Ochterlony, then an agent at Ludhiana, on 24 August 1814 noted of Dehra Dun as a "potentially thriving entrepot for Trans-Himalayan trade." He contemplated annexing Garhwal not so much with the view to revenue, but for security of commercial communications with the country where the shawl wool is produced. The British soon got to know that Kumaon provided a better facility for trade with Tibet. Therefore, the annexation of these two areas became part of their strategic objectives.

Security Concerns

Although the immediate cause of disputes between Nepal and the British occurred over territoriality, it is unlikely that the Company would have embarked on such an expensive and arduous war without a desire to “eliminate one of the few remaining threats to British dominance in northern India.”[14] Therefore, the Company’s security concerns also aided in causing the war. In the early nineteenth century before the Anglo-Nepalese War, Nepal’s land stood directly north of Bengal, the heart of British administration.[14] This posed a threat to the British. The Company feared that anti-British prejudices among the Nepalese might result in either an attack on Bengal that would strain British communication with North India, or may result in Indian states uniting into an anti-British alliance.[14] Gorkhas’ impressive conquests of the Kathmandu Valley further supplied the British with an exaggerated view of Nepal’s strength, contributing to the British viewing Nepal as a security threat.[14] Gorkhas’ strong resistance against British pressure since the 1760s contributed to British security concerns.[14]

The Treaty of Sagauli showcases British security concerns.[15] Article 6 of the treaty states, “The Raja of Nepal renounces for himself, his heirs, and successors, all claim to or connection with the countries lying to the west of the River Kali and engages never to have any concern with those countries or the inhabitants there of.”[15] This illustrates that the British used territorial limitations as a way of curtailing their security concerns – whether it be their concern over Nepal’s relationships with Sikhs, or concerns around Nepal’s possibility of alliance with north India or Bengal.

While trade was indeed a major objective of the company, out of it grew a concept of "political safety," which essentially meant a strategy of dissuasion and larger areas of occupation. The evidence does not support the claim that Hastings invaded Nepal only for commercial reasons. It was a strategic decision. He was wary of the Hindu revival and solidarity among the Marathas, the Sikhs, and the Gurkhas amid the decaying Mughal empire. He was hatching pre-emptive schemes of conquest against the Marathas in central India, and he needed to cripple Nepal first, in order to avoid having to fight on two fronts.[25]

That it was a flawed strategy is explained by P.J. Marshal: "Political safety meant military preparedness. The military expenditure for 1761–62 to 1770–71 was 44 percent of the total spending of 22 million pounds. War and diplomacy rather than trade and improvement; most of the soldiers-would-be politicians and Governor Generals rarely understood. The political safety of Bengal was their first priority and they interpreted safety as requiring the subjugation of Mysore, the Marathas, the Pindaris, the Nepalese and the Burmese."

War preparation

Pre-war opinions

When the Kathmandu Durbar solicited Nepalese chiefs' opinions about a possible war with the British, Amar Singh Thapa was not alone in his opposition, declaring that – "They will not rest satisfied without establishing their own power and authority, and will unite with the hill rajas, whom we have dispossessed. We have hitherto but hunted deer; if we engage in this war, we must prepare to fight tigers."[27] He was against the measures adopted in Butwal and Sheeoraj, which he declared to have originated in the selfish views of persons, who scrupled not to involve the nation in war to gratify their personal avarice.[27][28]

This contrasts sharply with the prime minister of Nepal, Bhimsen Thapa – " ... our hills and fastness are formed by the hand of God, and are impregnable."[29][30] This stance by Bhimsen Thapa is not surprising, as insinuated by Amar Singh, considering Amar Singh had made the usurpations in Butwal and Sheoraj, and whose family derived most of the advantages.[28] Prinsep estimates that the revenue of the usurped lands could not have been less than a lakh of rupees a year to the Nepalese, in the manner they collected it: the retention of this income was therefore an object of no small importance to the ambitious views of Bhimsen Thapa and the preservation of the influence he had contrived to establish for his family.[28] The Nepalese prime minister realized the Nepalese had several advantages over the British including knowledge of the region and recent experience fighting in the mountainous terrain. However, the British had numerical superiority and far more modern weapons.

In the meantime, the Governor-General also naively believed that "the difficulties of mountain warfare were greater on the defensive side than on that of a well conducted offensive operation."[21] Soldiers like Rollo Gillespie saw the Nepalese as a challenge to British supremacy — "Opinion is everything in such a country as India: and whenever the natives shall begin to lose their reverence for the English arms, our superiority in other respects will quickly sink into contempt."

Finance

The Governor-General looked towards the Nawab of Awadh to finance the impending warfare with Nepal: two crore (20 million) rupees were solicited. Of this matter he writes:[31]

...Saadut Ali[32] unexpectedly died. I found, however, that what had been provisionally agitated with him was perfectly understood by his successor,[33] so that the latter came forward with a spontaneous offer of a crore of rupees, which I declined as a peishcush or tribute on his accession to the sovereignty of Oude, but accepted as a loan for the Honourable Company. Eight lacs were afterwards added to this sum, in order that the interest of the whole, at six per cent, might equal the allowances to different branches of the Nawab Vizier's family, for which guarantee of the British Government had been pledged, and the payment of which, without vexatious retardments, was secured, by the appropriation of the interest to the specific purpose. The sum thus obtained was thrown into the general treasury, whence I looked to draw such portions of it as the demands of the approaching service might require. My surprise is not to be expressed, when I was shortly after informed from Calcutta, that it had been deemed expedient to employ fifty four lacs of the sum obtained by me in discharging an eight per cent loan, that the remainder was indispensable for current purposes, and it was hoped I should be able to procure from the Nawab Vizier a further aid for the objects of the war. This took place early in autumn, and operations against Nepaul could not commence till the middle of November, on which account the Council did not apprehend my being subjected to any sudden inconvenience through its disposal of the first sum. Luckily I was upon such frank terms with the Nawab Vizier, as that I could explain to him fairly my circumstances. He agreed to furnish another crore; so that the Honourable Company was accommodated with above two millions and a half sterling on my simple receipt.

In the aftermath of the war, he writes:[31]

The richest portion of the territory conquered by us bordered on the dominions the Nawab Vizier. I arranged the transfer of that tract to him in extinction of the second crore which I had borrowed. Of that crore the charges of the war absorbed fifty two lacs: forty eight lacs (£600,000) were consequently left in the treasury, a clear gain to the Honourable Company, in addition to the benefit of precluding future annoyance from an insolent neighbour.

This was in contrast with the Nepalese who had spent huge amount of resources on the first and second wars against the Tibetans, which had led to the gradual exhaustion of their treasury.

Terrain

To the British, who were used to fighting in the plains, but were unacquainted with the terrain of the hills, the formidability of the topology is expressed by one anonymous British soldier as such:[22]

...The territory subject to Nepal consists of a mountainous tract of country, lying between Tibet and the valley of the Ganges, in breadth not exceeding one hundred miles, but in length stretching nearly along the whole extent of the north-west frontier of the British dominions. Below the hills they held possession of a portion of the plain of irregular width, distinguished by the name of the Nepal Turrye,[34] but the period at which the acquisition was made is not ascertained.

The general military character of the country is that of extreme difficulty. Immediately at the front of the hills the plain is covered with the Great Saul Forest,[35] for an average width of ten or twelve miles; the masses of the mountains are immense, their sides steep, and covered with impenetrable jungle. The trenches in these ridges are generally water-courses, and rather chasms or gulfs than any thing that deserves the name of a valley. The roads are very insecure, and invariably pathways over mountains, or the beds of rivers, the usual means of transport throughout the country being by hill porters. Notwithstanding this general description, spaces comparatively open and hollow, and elevated tracts of tolerably level land, are to be met with, but so completely detached as to contribute but little to facilitate intercourse.

One of the largest and most fertile of these constitutes the valley of Nepal Proper.[36] To the westward of Nepal, there is a difficult tract, till the country again opens in the valley of Gorkah, the original possession of the present dynasty. – Westward of this the country is again difficult, till it somewhat improves in the district of Kemaoon.[37] Further to the westward lies the valley of the Dhoon,[38] and the territory of Sue-na-Ghur;[39] and further still, the more recent conquests, stretching to the village, in which Umar Sing,[40] a chief of uncommon talents, commanded, and indeed, exercised an authority almost independent.

First campaign

British plan of operation

The initial British campaign was an attack on two fronts across a frontier of more than 1,500 kilometres (930 mi), from the Sutlej to the Koshi. In the eastern front, Major-General Bennet Marley and Major-General John Sullivan Wood led their respective columns across the Tarai towards the heart of the valley of Kathmandu. Major-General Rollo Gillespie and Colonel David Ochterlony commanded columns in the western front. These columns were faced with the Nepalese army under the command of Amar Singh Thapa.[10] About the beginning of October, 1814, the British troops began to move towards different depots; and the army was soon after formed into four divisions, one at Benares, one at Meeruth, one at Dinapur, and one at Ludhiana.

The first division, at Dinapur, being the largest, was commanded by Major-General Marley, and was intended to seize the pass at Makwanpur, between Gunduk and Bagmati, the key to Nepal, and to push forward to Kathmandu: thus at once carrying the war into the heart of the enemy's country.[10][41] This force consisted of 8,000 men, including his Majesty's 24th foot of 907 strong; there was a train attached to it of four 18-pounders, eight 6- and 3-pounders, and fourteen mortars and howitzers.[42][43]

The second division, at Benares, under command of Major-General Wood, having subsequently removed to Gorakhpur, was meant to enter the hills by the Bhootnuill pass, and, turning to the eastward, to penetrate the hilly districts, towards Kathmandu, and cooperate with the first division, while its success would have divided the enemy's country and force into two parts, cutting off all the troops in Kumaon and Garhwal from communication with the capital.[10][41] Its force consisted of his Majesty's 17th foot, 950 strong, and about 3000 infantry, totaling 4,494 men; it had a train of seven 6- and 3-pounders, and four mortars and howitzers.[42][44]

The third division, was formed at Meerut, under Major-General Gillespie; and it was purposed to march directly to the Dehra Dun; and having reduced the forts in that valley, to move, as might be deemed expedient, to the eastward, to recover Srinagar from the troops of Amar Singh Thapa; or to the westward, to gain the post of Nahan, the chief town of Sirmaur, where Ranjore Singh Thapa held the government for his father, Amar Singh; and so sweep on towards the Sutlej, in order to cut off that chief from the rest, and thus to reduce him to terms.[10][41] This division originally consisted of his Majesty's 53d, which with artillery and a few dismounted dragoons, made up about one thousand Europeans, and two thousand five hundred native infantry, totaling 3,513 men.[42][44]

The fourth, or north-western division, at Ludhiana, was to operate in the hilly country lying near the Sutlej: it assembled under Brigadier-General Ochterlony, and was destined to advance against the strong and extensive cluster of posts held by Amar Singh and the troops under his immediate orders at and surrounding Irkee, a considerable town of Kahlur, and to cooperate with the forces under Major-General Gillespie, moving downwards among the hills, when these positions should be forced, surrounding Amar Singh, and driving him upon that army.[10][41] The force consisted exclusively of native infantry and artillery, and amounted to 5,993 men; it had a train of two 18-pounder, ten 6-pounders, and four mortars and howitzers.[42][45]

Lastly, beyond the Koshi River eastward, Major Latter was furnished with two thousand men, including his district battalion, for the defence of the Poornea frontier. This officer was desired to open a communication with the Raja of Sikkim, and to give him every assistance and encouragement to expel the Gorkhas from the eastern hills, short of an actual advance of troops for the purpose.[43] Captain Barré Latter was sent to the border with Poornea and after a successful mission to confine the Gorkhas to their own territory concluded the Anglo-Sikkimese Treaty of Titalia confirming the Raja's dominions, although the latter lost territory from his border to the Tamur River.[46]

The Commander-in-Chief of the British forces was Lord Moira. All four divisions composed mostly of Indian Sepoys. Ochterlony's army was the only division without a single British battalion. In conclusion, the Gorkhali Army defeated the British on three fronts consisting the middle and the east whereas lost the remaining two fronts in the west.

Battle of Makwanpur Gadhi

Major General Marley was tasked to occupy Hetauda and capture the fortresses of Hariharpur and Makawanpur before proceeding to Kathmandu. His frontage of advance lay between Rapati river and Bagmati river. After additional reinforcements, he had 12,000 troops for his offensive against the Makawanpur and Hariharpur axis. A big attack base was established but Major General Marley showed reluctance to take risks against the Nepalese. Some skirmishes had already started taking place. Similarly, Major General George Wood, sometimes known as the Tiger of the British Indian Army, proved exceedingly cautious against the hard charging Nepalese.

Colonel[47] Ranabir Singh Thapa, brother of Bhimsen Thapa, was to be the Sector Commander of Makawanpur-Hariharpur axis. He was given a very large fortress and about 4,000 troops with old rifles and a few pieces of cannons. But the British could not move forward from the border. Colonel Ranabir Singh Thapa had been trying to lure the enemies to his selected killing area. But Major General Wood would not venture forward from Bara Gadhi and he eventually fell back to Betiya.

Battle of Jitgadh

With the help of an ousted Palpali king, Major General Wood planned to march on Siuraj, Jit Gadhi and Nuwakot with a view to bypass the Butwal defenses, flushing out minor opposition on the axis, and assault Palpa from a less guarded flank. Nepalese Colonel Ujir Singh Thapa had deployed his 1200 troops in many defensive positions including Jit Gadhi, Nuwakot Gadhi and Kathe Gadhi. The troops under Colonel Ujir were very disciplined and he himself was a dedicated and able commander. He was famous for exploiting advantage in men, material, natural resources and well versed in mountain tactics. The British advance took place on January 6, 1814, to Jit Gadh. While they were advancing to this fortress, crossing the Tinau River, the Nepalese troops opened fire from the fortress. Another of the attackers' columns was advancing to capture Tansen Bazar. Here too, Nepalese spoiling attacks forced the General to fall back to Gorakhpur. About 70 Nepalese lost their lives in Nuwakot pakhe Gadhi. Meanwhile, more than 300 of the enemy perished.

Battle of Hariharpur Gadhi

No special military action had taken place in Hariharpur Gadhi fortress in the first campaign. Major General Bannet Marley and Major General George Wood had not been able to advance for an offensive against Makawanpur and Hariharpur Gadhi fortresses.

Battle of Nalapani

The Battle of Nalapani was the first battle of the Anglo-Nepalese War. The battle took place around the Nalapani fort, near Dehradun, which was placed under siege by the British between 31 October and 30 November 1814. The fort's garrison was commanded by Captain Balbhadra Kunwar, while Major-General Rollo Gillespie, who had previously fought at the Battle of Java, was in charge of the attacking British troops. Gillespie was killed on the first day of the siege while rallying his men and despite considerable odds, both in terms of numbers and firepower, Balbhadra and his 600-strong garrison, which also consisted of brave women who reportedly shielded the bullets and cannonballs with their bodies, successfully held out against more than 5,000 British troops for over a month. Fraser recorded the situation in the following terms:[48]

The determined resolution of the small party which held this small post for more than a month, against so comparatively large a force, must surely wring admiration from every voice, especially when the horrors of the latter portion of this time are considered; the dismal spectacle of their slaughtered comrades, the sufferings of their women and children thus immured with themselves, and the hopelessness of relief, which destroyed any other motive for their obstinate defence they made, than that resulting from a high sense of duty, supported by unsubdued courage. This, and a generous spirit of courtesy towards their enemy, certainly marked the character of the garrison of Kalunga, during the period of its siege.

Whatever the nature of the Gurkhas may have been found in other quarters, there was here no cruelty to wounded or to prisoners; no poisoned arrows were used; no wells or waters were poisoned; no rancorous spirit of revenge seemed to animate them: they fought us in fair conflict, like men; and, in intervals of actual combat, showed us a liberal courtesy worthy of a more enlightened people.

So far from insulting the bodies of the dead and wounded, they permitted them to lie untouched, till carried away; and none were stripped, as is too universally the case.

After two costly and unsuccessful attempts to seize the fort by direct attack, the British changed their approach and sought to force the garrison to surrender by cutting off the fort's external water supply. Having suffered three days of thirst, on the last day of the siege, Balbhadra, refusing to surrender, led the 70 surviving members of the garrison in a charge against the besieging force. Fighting their way out of the fort, the survivors escaped into the nearby hills. The battle set the tone for the rest of the Anglo-Nepalese War, and a number of later engagements, including one at Jaithak, unfolded in a similar way.

The experience at Nalapani so discomforted the British that Lord Hastings so far varied his plan of operations as to forego the detachment of a part of this division to occupy Gurhwal.[49] He accordingly instructed Colonel Mawbey to leave a few men in a strong position for the occupation of the Doon and to carry his undivided army against Amar Singh's son, Colonel Ranajor Singh Thapa, who was with about 2300 elite of the Gurkha army, at Nahan.[49] It was further intended to reinforce the division considerably; and the command was handed over to Major-General Martindell.[49] In the meantime Colonel Mawbey had led back the division through the Keree pass, leaving Colonel Carpenter posted at Kalsee, at the north western extremity of the Doon.[50] This station commanded the passes of the Jumna on the main line of communication between the western and eastern portions of the Gurkha territory, and thus was well chosen for procuring intelligence.[50]

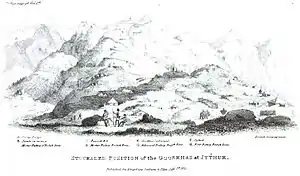

Battle of Jaithak

Major General Martindale now joined the force and took over command. He occupied the town of Nahan on 27 December, and started his attack on the fort of Jaithak. The fort had a garrison of 2000 men under the command of Ranajor Singh Thapa, the son of the Amar Singh Thapa. The first assault ended in disaster, with the Nepalese successfully warding off the British offensive. The second managed to cut off the water supply to the fort, but could not capture it mainly because of the exhausted state of the troops and shortage of ammunition. Martindale lost heart and ordered a withdrawal. Jaithak was eventually captured much later in the war, when Ochterlony had taken over the command.[51]

A single day of battle at Jaithak cost the British over three hundred men dead and wounded and cooled Martindell's ardour for battle. For over a month and a half, he refused to take any further initiative against the Nepalese army. Thus by mid-February, of the four British commanders the Nepalese army had faced till that time, Gillespie was dead, Marley had deserted, Wood was harassed into inactivity, and Martindell was practically incapacitated by over-cautiousness. It set the scene for Octorloney to soon show his mettle and change the course of the war.

Trying times for Nepalese troops

Out West, the Nepalese were hopelessly overextended. Kumaun, a key link in Nepalese army communications with the Far West, was defended by a small force, numbering about seven hundred and fifty men, with an equal number of Kumaoni irregulars, altogether about fifteen hundred men to defend a whole province. In addition, Doti which was to the East of Kumaun, had been practically stripped of troops. Bam Shah, as governor of Kumaun, had final responsibility for the defence of the province.

The British force, numbering initially over forty five hundred men, was easily able to outmanoeuvre the Nepalese army defenders and force them to abandon one post after another. Despite a significant victory over Captain Hearsey's force, which had been sent on a flanking movement though Eastern Kumaun, and the capture of the captain himself, the Nepalese army was unable to stem the tide of the British advance. Hasti Dal Shah arrived in Almora with a small body of reinforcement troops. A further reinforcement of four companies was sent from Kathmandu to aid the beleaguered defences of Kumaun, but the difficulties of communication through the hills prevented them from arriving in time to be of any help.

Meanwhile, Hastings sent Colonel Nicolls, Quartermaster-General for the British troops in India, to take charge of the Almora campaign and assigned two thousand regular troops to this front in addition to the very large number of irregulars already assigned to the area – all of this against fewer than one thousand Nepalese army soldiers.

Hasti Dal Shah and some five hundred Nepalese Army men had set out from Almora to secure Almora's Northern line of communications with Kathmandu. This party was intercepted. Hasti Dal Shah, the ablest Nepalese commander in this sector, was killed in the first moments of the battle. The Nepalese suffered terrible losses. When word of this disaster reached the defenders at Almora, they were stunned. The British closed in on Almora and the Nepalese was unable to prevent the British advance. On April 25, 1815, 2,000 British regulars under Col. Nicholls and a force of irregular troops under Col. Gardiner assaulted and captured the heights of the town of Almorah. Subsequently, the British managed to establish gun positions within seventy yards of the gate of the fort at Almora and the British artillery demolished the walls of the fort at point blank range. Bam Shah surrendered Almora on 27 April 1815. The result of this British victory was the capitulation of the province of Kumaon and all of its fortresses.

Second Battle of Malaon and Jaithak

The second battle of Malaon and Jaithak cut the Nepalese lines of communication between Central Nepal and the Far West. It also sealed the fate of Kazi Amar Singh Thapa at Malaon and Ranajor Singh Thapa at Jaithak. At Malaon, Major-General Ochterlony had moved with extreme care summoning reinforcements and heavy guns from Delhi until his total attack force consisted of over ten thousand men well-equipped with heavy cannon.

Kazi Amar Singh Thapa's position in the Malaon Hills depended on Bilaspur in the lowlands for his food supplies, and the nature of the hills forced him to spread his forces very thinly in an attempt to defend every vantage point. Ochterlony cut off the supply of food from Bilaspur and then turned his attention to the intricate network of defensive posts that were designed to withstand any frontal assault. Although rear fortifications supported these posts, none could withstand a long cannonade by heavy guns. Because Ochterlony had sufficient troops to attack and overwhelm several positions simultaneously, the thinly spread Nepalese defences could be dangerously divided.

Ochterlony chose his target, a point on the ridge, and then proceeded to move slowly, consolidating each position that he took, and allowing the pioneers time to build roads so that the heavy guns could be moved forward to support each attack. After a series of carefully planned and executed moves, he succeeded in establishing a position on the crest of Deothal, not even over a thousand yards from Kazi Amar Singh Thapa's main fort at Malaon. The old warrior Bhakti Thapa valiantly led assault after assault on this position, but he died during battle and the position did not fall. Immensely impressed by Bhakti's sustained courage against impossible odds, the British made the well appreciated and honourable gesture of returning his body with full military honours. The British superiority in numbers made it inevitable that they would be able to establish themselves and their heavy guns on a vantage point within range of Ranajor Singh's fortifications, sooner or later.

Both Kazi Amar Singh Thapa and Ranajor Singh Thapa were thus hemmed in and looking down the barrels of the British guns when Bam Shah's letter arrived, announcing the fall of Almora. Although the old commander was still reluctant to surrender, Kazi Amar Singh Thapa at last saw the hopelessness of the situation and, compelled by circumstances and the British guns, surrendered with honour for both himself and Ranajor Singh. The Nepalese positions in the Far West lost control to the British on 15 May 1815.

Second campaign

The outstretched Nepalese army was defeated on the Western front i.e. Garhwal and Kumaon area. Ochterlony had finally outfoxed Bada Kaji Amar Singh Thapa. He was the only successful British Commander in the first Nepal-Company campaign. Not surprisingly Lord Moira appointed him as the Main Operational Commander in the second offensive on the Bharatpur-Makawanpur-Hariharpur front with 17,000 strong invasion force, but again, most of them were Indian sepoys.[52]

The British had given a 15-day ultimatum to Nepal to ratify a treaty on 28 November. But the points of the treaty were very difficult for the Nepalese to ratify quickly. The delay provided the excuse for the British to commence the second military campaign against the kingdom. Colonel Bhaktawar Singh Thapa, another brother of Bhimsen Thapa, had been appointed as Sector Commander for defensive battles for the area from Bijayapur to Sindhuli Gadhi in the first campaign. In this second campaign, Bada Kaji Amarsingh Thapa[note 3]was detailed as Sector Commander for Sindhuli Gadhi and the eastern front. Colonel Bhaktawar Singh Thapa was manning his headquarters at Makwanpur Gadhi. Major General David Ochterlony, was the overall commander against Nepal with a massive 17,000 British troops to assault the fronts including Upardang Gadhi, Sinchyang Gadhi, Kandrang Gadhi, Makawanpur Gadhi and Hariharpur Gadhi.

During the campaign in February 1816, Ochterlony decided to take a very infrequently used pass through the mountains. The failure there would have been a disaster for British. But the successful passage would allow British to directly emerge and attack the Nepalese's rear. Colonel Kelly and Colonel O’Hollorah followed the river Bagmati to reach Hariharpur Gadhi. Some of the heads of villagers were bribed for sensitive information about the defensive positions in the area of Hariharpur Gadhi. The information seriously compromised the Nepalese defences. Secret routes would have given the enemy advantage even if they were able to get only a battalion through. But the British were able to advance with more than a brigade's strength. Colonel Kelly and Colonel O’Hollorah launched their attack from two different directions on 29 February. The Nepalese troops were eventually driven back from Hariharpur Gadhi after a big battle. Kaji Ranjore Singh Thapa withdrew to Sindhuli Gadhi to link up with Bada Kaji Amar Singh Thapa. The British troops did not approach Sindhuli Gadhi and fell back to Makawanpur by the end of March 1816.

The situation became very critical for Nepal and the British which eventually led to a treaty. Major General David Ochterlony settled down to receive the treaty, signed by Kathmandu Durbar through Chandra Sekhar Upadhyaya, Pandit Gajaraj Mishra and finally though Bhaktawar Singh Thapa. Two days later the ratified treaty was handed over to the British in Makawanpur. The war ended with the Treaty of Sugauli, which has been considered as an unequal treaty which led to Nepal losing its one-third territory. The river Mechi became the new Eastern border and the Mahakali the Western boundary of Nepal.

Aftermath

The Treaty of Sugauli

The Treaty of Sugauli was ratified on 4 March 1816. As per the treaty, Nepal lost all Sikkim (including Darjeeling), the territories of Kumaon and Garhwal and Western Terai. The Mechi River became the new eastern border and the Mahakali river the western boundary of the kingdom. The British East India Company would pay 200,000 rupees annually to compensate for the loss of income from the Terai region. The British set up Resident.[53] The fear of having a British Resident in Kathmandu ultimately proved to be unfounded, as the rulers of Nepal managed to isolate the Resident to such an extent as to be in virtual house arrest.

The Terai lands, however, proved difficult for the British to govern and some of them were returned to the kingdom later in 1816 and the annual payments accordingly abolished.[54] However even after the conclusion of the Anglo-Nepalese War, the border issue between the two states was not yet settled. The boundary between Nepal and Oudh was not finally adjusted until 1830; and that between Nepal and the British territories remained as a matter of discussion between the two Governments for several years later.[55]

The British never had the intention to destroy either the existence or the independence of a state which was usefully interposed between them and the dependencies of China.[56] Lord Hastings had given up his plan to dismember Nepal from fear of antagonising China – whose vassal Nepal in theory was. In 1815, while British forces were campaigning in far western Nepal, a high-ranking Manchu official advanced with a large military force from China to Lhasa; and the following year, after the Anglo-Nepalese treaty had been signed, the Chinese army moved south again, right up to Nepal's frontier. The Nepalese panicked, because memories were still vivid of the Chinese invasion of 1792, and there was a flurry of urgent diplomatic activity. Hastings sent mollifying assurances to the imperial authorities, and ordered the British Resident, newly arrived in Kathmandu, to pack his bags and be ready to leave at once if the Chinese invaded again.[57]

Cost of war

Despite the boast of Lord Moira to the British parliament on having increased the state coffers, the Gurkha War had in reality cost more than the combined cost of the campaigns against the Marathas and the Pindaris for which Lord Moira's administration is better known: Sicca Rs. 5,156,961 as against Sicca Rs. 3,753,789.[58] This was the kind of fact which greatly influenced the policy of the Company government in subsequent years. Thus, while the Company Government, in theory, thoroughly approved of the development of trade, especially in shawl wool, between Western Tibet and its territories, it was unprepared to take any decisive step to bring this about. It preferred to leave the Chinese in Tibet to their own devices, and hoped to avoid the risk, however slight, of another expensive hill war.[58]

Furthermore, despite the British merchants' direct access to the wool growing areas after the war, the hopes of shawl wool trade were never realised. The British merchants found that they were too late. The shawl wool market was strictly closed and closely guarded. It was monopolised by traders from Kashmir and Ladakh, and the only outsider with whom they dealt was Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the powerful Sikh ruler of Lahore. Ranjit was very zealous of his privilege, and he was the last person the British could afford to offend at this time of crisis and uncertainty. So the East India Company never did get its shawl wool. When it finally acquired the Punjab and Kashmir, after the Sikh Wars of the 1840s, it had long since given up trade, and Kashmir was so little valued that it was quickly discarded – sold for a knock-down price to the Raja of Jammu.[59]

Gorkha recruitment

David Ochterlony and the political agent William Fraser were quick to recognize the potential of Nepalese soldiers in British service. During the war the British were keen to use defectors from the Nepalese army and employ them as irregular forces. His confidence in their loyalty was such that in April 1815 he proposed forming them into a battalion under Lieutenant Ross called the Nasiri regiment. This regiment, which later became the 1st King George's Own Gurkha Rifles, saw action at the Malaun fort under the leadership of Lieutenant Lawtie, who reported to Ochterlony that he "had the greatest reason to be satisfied with their exertions".

As well as Ochterlony's Gorkhali battalions, William Fraser and Lieutenant Frederick Young raised the Sirmoor battalion, later to become the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles; an additional battalion, the Kumaon battalion was also raised eventually becoming the 3rd Queen Alexandra's Own Gurkha Rifles. None of these men fought in the second campaign.

Fate of protagonists

Bhimsen Thapa

Prime Minister Bhimsen Thapa, with the support of the queen regent Tripura Sundari, remained in power despite the defeat of Nepal. Other ruling families, particularly the Pandes, decried what they saw as Bhimsen Thapa's submissive attitude towards the British. The prime minister however had been able to retain power by maintaining a large, modernized army and politically dominating the court during the minority of King Rajendra Bikram Shah, (reigned 1816–1847). Additionally, he was able to freeze out the Pandes from power by appointing members of his own family into positions of authority.

When queen Tripura Sundari died in 1832, Bhimsen Thapa began to lose influence. In 1833, Brian Hodgson became British resident, openly favouring Bhimsen Thapa's opponents, and in 1837 the king announced his intention to rule independently, depriving the prime minister and his nephew of their military powers. After the eldest son of the queen died, Bhimsen Thapa was falsely accused of attempting to poison the prince. Although acquitted, the Thapas were in turmoil. When the head of the Pande family, Rana Jang Pande, became prime minister, he had Bhimsen Thapa re-imprisoned; Bhimsen Thapa committed suicide in August 1839.

David Ochterlony

For his part, David Ochterlony received thanks from both Houses of Parliament and became the first officer in the British East India Company to be awarded the GCB. Lord Moira also reinstated him as Resident at Delhi and he lived in the style appropriate to a very senior figure of the company. However, after Lord Moira left India – succeeded by Lord Amherst as Governor-General in 1823 – Ochterlony fell out of favor.

In 1825 the Raja of Bharatpur died and the six-year-old heir to the throne, whom Ochterlony supported, was usurped by his cousin Durjan Sal. When Durjan Sal failed to submit to Ochterlony's demands to vacate the throne, the British general prepared to march on Bharatpur. He did not receive the backing of the new Governor-General however, and after Amherst countermanded his orders, Ochterlony resigned, as Amherst had anticipated. This episode badly affected the ailing general who died shortly after on 14 July 1825. A 165-foot-high memorial was later erected in Calcutta in his memory; however, Sir David Ochterlony's greatest legacy is the continuing recruitment of Gorkhas into the British and Indian armies.

Soon after Ochterlony's resignation Amherst was himself obliged to do what Ochterlony had prepared to do, and laid siege to Bharatpur.[52]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Not to be confused with the better known commander of Gorkhali forces in the Gurkha War with the same name. The two Amar Singhs are differentiated by the qualifier Bada (greater) and Sanu (lesser).

- ↑ Bhimsen's nephew Ujir Singh Thapa[7] commanded over the Butwal-Jitgadhi Axis, and his brothers (Ranbir Singh Thapa and Bakhtawar Singh Thapa) commanded over the Makwanpur-Hariharpur Axis and Bijayapur-Sindhuligadhi Axis, respectively.[8] Bada Kaji Amar Singh Thapa, who was considered a member of the larger Thapa caucus,[9] led the battle as overall commander against the columns of Major-General Rollo Gillespie and Colonel David Ochterlony. His son Ranjore Thapa commanded the Nahan and Jaithak forts.[10] Ranjor's nephew Balbhadra Kunwar[11] commanded the Doon region at the Battle of Nalapani.[12]

- ↑ Not to be confused with the better known commander of Gorkhali forces in the Gurkha War with the same name. The two Amar Singhs are differentiated by the qualifier Bada (greater) and Sanu (lesser).

References

- ↑ "Britisch-Nepalischer Krieg 1814-1816". www.bilder-aus-nepal.de.

- ↑ Pradhan 2012, p. 50.

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of the British Empire: A-J, Volume 1; Volume 6, pp. 493

- ↑ The Victorians at war, pp.155

- ↑ Naravane (2006), p. 189

- ↑ Smith 1852, p. 218

- ↑ Prinsep 1825, p. 115.

- ↑ "History of the Nepalese Army". nepalarmy.mil.np. Nepal Army. Archived from the original on 28 December 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ↑ Pradhan 2012, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Anon 1816, p. 427.

- 1 2 Acharya 1971, p. 3.

- ↑ Prinsep 1825, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Caplan, Lionel. “‘Bravest of the Brave’: Representations of ‘The Gurkha’ in British Military Writings.” Modern Asian Studies 25, no. 3 (1991): 571–97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/312617.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rose, Leo E. Nepal: Strategy for Survival. 1st ed. University of California Press, 1971.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bradshaw, Parish and Gajaraj, Mishra, “Treaty of Sugauli,” 1816. Historic Treaties and Documents, Archive Nepal. https://www.archivenepal.org/treatiescollection.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Michael, Bernardo A. “Writing a World History of the Anglo-Gorkha Borderlands in the Early Nineteenth Century.” Journal of World History 25, no. 4 (2014): 535–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43818464.

- 1 2 Anon 1816, p. 425.

- 1 2 3 Oldfield 1880, p. 40

- ↑ Smith 1852, Warlike Preliminaries, Ch. 8, p. 172

- ↑ Prinsep 1825, Causes of Nipal War, p. 54-80

- 1 2 3 4 Hastings 1824, p. 9

- 1 2 Anon 1816, p. 426.

- ↑ Smith, Britain's Declaration of War, p.187-212.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 English, Richard. “Himalayan State Formation and the Impact of British Rule in the Nineteenth Century.” Mountain Research and Development 5, no. 1 (1985): 61–78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3673223.

- 1 2 3 Pemble, Forgetting and remembering Britain's Gurha War 2009, p. 366

- ↑ Cowan, Sam (30 November 2022). "The battle for the ear of the emperor - The Record". The Record. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- 1 2 Prinsep 1825, p. 460

- 1 2 3 Prinsep 1825, pp. 79–80

- ↑ Prinsep 1825, p. 458: The entire letter by Bhimsen Thapa is as follows: "Through the influence of your good fortune, and that of your ancestors, no one has yet been able to cope with the state of Nipal. The Chinese once made war upon us, but were reduced to seek peace. How then will the English be able to penetrate into the hills? Under your auspices, we shall by our own exertions be able to oppose to them a force of fifty-two lakhs of men, with which we will expel them. The small fort of Bhurtpoor was the work of man, yet the English being worsted before it, desisted from the attempt to conquer it; our hills and fastnesses are formed by the hand of God, and are impregnable. I therefore recommend the prosecution of hostilities. We can make peace afterwards on such terms as may suit our convenience."

- ↑ Hunter 1896, p. 100

- 1 2 Hastings 1824, pp. 9–10

- ↑ Saadat Ali Khan II

- ↑ Ghazi-ud-Din Haider

- ↑ Terai

- ↑ Shorea robusta, also known as sal or shala tree, is a species of tree belonging to the family Dipterocarpaceae.

- ↑ "Nepal Proper" refers to the Kathmandu Valley. Before the conquest of the Kathmandu Valley by Prithvi Narayan Shah, only this valley was originally referred to as Nepal.

- ↑ Kumaon

- ↑ Dehradun

- ↑ Srinagar, Uttarakhand

- ↑ Amar Singh Thapa

- 1 2 3 4 Fraser 1820, p. 13

- 1 2 3 4 Smith 1852, Plan of Operation, p. 215-219

- 1 2 Prinsep 1825, p. 85

- 1 2 Prinsep 1825, p. 84

- ↑ Prinsep 1825, p. 83

- ↑ Paget, William Henry (1907). Frontier and overseas expeditions from India. p. 40.

- ↑ The use of English terms for their grades of command was common in the Nepalese army, but the powers of the different ranks did not correspond with those of the British system. The title of General was assumed by Bhimsen Thapa, as Commander-in-chief, and enjoyed by himself alone; of Colonels there were three or four only; all principal officers of the court, commanding more than one battalion. The title of Major was held by the adjutant of a battalion or independent company; and Captain was the next grade to colonel, implying the command of a corps. Luftun, or Lieutenant, was the style of the officers commanding companies under the Captain; and then followed the subaltern ranks of Soobadar, Jemadar, and Havildar, without any Ensigns. (Prinsep 1825, pp. 86–87)

- ↑ Shackell 1820, p. 590

- 1 2 3 Prinsep 1825, p. 94

- 1 2 Prinsep 1825, p. 95

- ↑ Naravane 2006, p. 190

- 1 2 Naravane (2006), p. 191

- ↑ India-Board (8 November 1816) in Kathmandu.

- ↑ Oldfield 1880, pp. 304–305

- ↑ Oldfield 1880, p. 306

- ↑ Anon 1816, p. 428.

- ↑ Pemble, Forgetting and remembering Britain's Gurha War 2009, p. 367

- 1 2 Lamb 1986, p. 41

- ↑ Pemble, Forgetting and remembering Britain's Gurha War 2009, pp. 366–367

Sources

Primary sources

- India-Board. (16 August 1815). Dispatches, dated Fort-William, 25 January 1815. The London Gazette. Issue: 17052. Published: 19 Aug 1815. pp. 1–8.

- India-Board. (8 November 1816). Dispatches, dated Fort-William, 30 March 1816. The London Gazette. Issue: 17190. Published: 11 Nov 1816. pp. 1–4.

- Anon (May 1816), "An account of the war in Nipal; Contained in a Letter from an Officer on the Staff of the Bengal Army", Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany, 1: 425–429

- Fraser, James Baillie (1820), Journal of a tour through part of the snowy range of the Himālā mountains, and to the sources of the rivers Jumna and Ganges, London: Rodwell and Martin

- Anon (1822), Military sketches of the Goorka war in India: in the years 1814, 1815, 1816, London: Woodbridge, Printed by J. Loder for R. Hunter

- East India Company. (1824). Papers respecting the Nepaul War. Papers regarding the administration of the Marquis of Hastings in India.

- Hastings, Marquis of (1824), Summary of the operations in India: with their results: from 30 April 1814 to 31 Jan. 1823

- Prinsep, Henry Thoby (1825), History of the political and military transactions in India during the administration of the Marquess of Hastings, 1813–1823, Vol 1, London: Kingsbury, Parbury & Allen

- Shackell, W. (1820), The Monthly Magazine. Volume: XLIX Part: I for 1820

Secondary sources

- Acharya, Baburam (1 January 1971) [1950], "King Girvan's letter to Kaji Ranjor Thapa" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 3 (1): 3–5

- Smith, Thomas (1852), Narrative of a five-year's residence at Nepaul. Vol 1, London: Colburn and Co.

- Oldfield, Henry Ambrose (1880), Sketches from Nipal, Vol 1, London: W.H. Allen and Co.

- Hunter, William Wilson (1896), Life of Brian Houghton Hodgson, London: John Murray

- Lamb, Alastair (1986) [1960], British India and Tibet 1766–1910 (Revised ed.), Routledge, pp. 26–43, ISBN 0710208723

- Gould, Tony (2000), Imperial Warriors – Britain and the Gorkhas, Granta Books, ISBN 1-86207-365-1

- Naravane, M. S. (2006), Battles of the honourable East India Company: Making of the Raj, APH Publishing, pp. 189–191, ISBN 978-81-313-0034-3

- Pemble, John (2009), "Forgetting and remembering Britain's Gurkha War", Asian Affairs, 40 (3): 361–376, doi:10.1080/03068370903195154, S2CID 159606340

- Pemble, John. (2009). Britain's Gorkha War: The Invasion of Nepal, 1814–16. Casemate Pub & Book Dist Llc ISBN 978-1-84832-520-3.

- Pradhan, K. L. (2012). Thapa politics in Nepal : with special reference to Bhim Sen Thapa, 1806-1839. New Delhi: Concept Pub. Co. ISBN 9788180698132.

- Nepalese Army Headquarters (2010), The Nepalese Army, ISBN 978-9937-2-2472-7, archived from the original on 26 January 2013, retrieved 3 February 2012

Bibliography

- Marshall, Julie G. (2005). Britain and Tibet 1765-1947: a select annotated bibliography of British relations with Tibet and the Himalayan states including Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-33647-3