Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Lev Bezymenski |

|---|---|

| Original title | Der Tod des Adolf Hitler: Unbekannte Dokumente aus Moskauer Archiven[lower-alpha 1] |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Publisher | Wegner |

Publication date | 1968 |

Published in English | 1968 |

| Media type | Print (paperback) |

| Pages | c. 134 |

The Death of Adolf Hitler: Unknown Documents from Soviet Archives[lower-alpha 1] is a 1968 book by Soviet journalist Lev Bezymenski, who served as an interpreter in the Battle of Berlin. The book gives details of the purported Soviet autopsies of Adolf Hitler, Eva Braun, Joseph and Magda Goebbels, their children, and General Hans Krebs. Each of these individuals are recorded as having been subjected to cyanide poisoning; contrary to the Western conclusion (and the accepted view of historians) that Hitler died by a suicide gunshot.

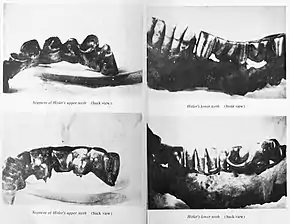

The book's release was preceded by various contradictory reports about Hitler's death, including from eyewitnesses. Under Joseph Stalin, the Soviets both claimed that Hitler died from cyanide and that he escaped Berlin. Much of the information presented in the book about how Hitler died (namely by poisoning or a coup de grâce) has been discredited, including by the author, as propaganda. Hitler's body was reputedly burned almost completely to ashes, meaning that there would be no corpse to conduct an autopsy upon. Only the Soviet description of Hitler's dental remains, consisting of a golden bridge and a mandibular fragment with teeth, is regarded as reliable; the book includes previously unreleased photographs of these.

Background

On 22 April 1945, as the Red Army was closing in on the Führerbunker during the Battle of Berlin, Hitler declared that he would remain in Berlin until the end and then shoot himself.[2] That same day, he asked Schutzstaffel (SS) physician Werner Haase about the most reliable method of suicide; Haase suggested combining a dose of cyanide with a gunshot to the head.[3] SS physician Ludwig Stumpfegger provided Hitler with some ampoules of prussic acid (hydrogen cyanide), which the dictator initially planned to use but later doubted their efficacy. On 29 April, Hitler ordered Haase to test one of the ampoules on his dog Blondi; the dog died instantly.[4] On the afternoon of 30 April, Hitler committed suicide with Eva Braun in his bunker study.[5] The former Reich minister of propaganda and Hitler's successor as chancellor of Germany, Joseph Goebbels, informed the Reichssender Hamburg radio station, which broke the initial news of Hitler's death on the night of 1 May.[6]

Bezymenski's 1968 book on Hitler's death was presaged by various contradictory reports regarding that event and its primary investigations.

Initial Soviet surveys

On 9 May 1945, The New York Times reported that a body was claimed by the Soviets to belong to Hitler, but that an anonymous servant disputed this—claiming that the body belonged to a cook who was killed because of his resemblance to the (allegedly escaped) dictator.[7][8] By 11 May, two colleagues of Hitler's dentist, Hugo Blaschke,[lower-alpha 2] confirmed the dental remains of Hitler and Eva Braun;[9] both subsequently spent years in Soviet prisons.[10]

On 5 June, Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov's staff officers stated that Hitler's body had been examined and claimed that he had died by cyanide poisoning.[11] At a press conference on 9 June, on orders from Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, Zhukov presented the official narrative that Hitler did not commit suicide, but had escaped Berlin—beginning a Soviet disinformation campaign suited to Stalin's desires.[12] The next day, newspapers quoted Zhukov as saying, "We have found no corpse that could be Hitler's," and Soviet Colonel General Nikolai Berzarin as stating, "Perhaps he is in Spain with Franco."[13] In early July, Time magazine cited the ongoing Soviet investigation as having produced no conclusive evidence and asserting that Hitler had ordered his men to spread news of his death.[14]

When asked at the Potsdam Conference in July 1945 how Hitler had died, Stalin said he was either living "in Spain or Argentina."[15] The same month, British newspapers quoted a Soviet officer as saying that a charred body they had discovered was "a very poor double." United States newspapers quoted the Russian garrison commandant of Berlin as claiming that Hitler had "gone into hiding somewhere in Europe," possibly with the help of Francoist Spain.[16] In mid-1945, a Soviet major told American sources that Hitler had survived and claimed of the place in the Reich Chancellery garden where his body was said to have been burned, "It is not true that Hitler was found there!”. He went on to claim they did not find the body of Eva Braun, either.[17][18][19]

According to SS valet Heinz Linge, who was captured by the Soviets in early May 1945, his interrogators repeatedly questioned him about whether Hitler was dead or if he could have escaped and perhaps left a double in his place; the Soviets told him that they had found a number of corpses but were unsure about Hitler's remains.[20] In 1956, the German tabloid Das Bild quoted the Soviet People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) Captain Fjedor Pavlovich Vassilki as claiming, "Hitler's skull was [found] almost intact, as were the cranium and the upper and lower jaws."[21]

Eyewitness accounts

Three main eyewitnesses to the state of Hitler and Braun's bodies in the immediate aftermath of their deaths survived and provided their accounts: Linge, SS-Sturmbannführer Otto Günsche, and Hitler Youth leader Artur Axmann.[22][lower-alpha 3] Contrarily, in a purported Soviet transcript of a statement made on 17 May 1945 (and not released for six decades), Günsche allegedly first saw the bodies after they had been wrapped in blankets.[25] British MI6 intelligence officer Hugh Trevor-Roper argued that discrepancies in truthful eyewitness accounts could be due to differences in "observation and recollection",[26] while German historian Anton Joachimsthaler interpreted them as possibly being due to poor memory formation during the turbulent event.[27] The three key eyewitnesses agree in their reports to Western authorities that Hitler was found seated upright at the end of the sofa (or in an armchair next to it) and Braun was next to him with no visible wounds.[28] (SS-Oberscharführer Rochus Misch was also interrogated by the Soviets; over half a century later, he told U.S. interviewers that he saw Hitler's head facedown on the table, contradicting himself about whether he saw blood. Braun's head was purportedly leaning against Hitler's leg.)[29][30]

After his capture in December 1945,[23] Axmann told U.S. officials that he saw thin ribbons of blood coming from both of Hitler's temples and that his lower jaw seemed slightly askew, leading him to think that Hitler had shot himself through the mouth—with the temple blood a result of internal trauma.[31][32][lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5] Axmann did not check the back of the head for an exit wound.[31][36] Axmann made other contradictory statements thereafter, such as reportedly being told Hitler used the pistol and poison method for suicide and that the shot in the mouth destroyed his dental work.[37][32][31][22][38][lower-alpha 6][lower-alpha 7] In 1948, the Berlin Records Office cited Axmann's testimony from the Einsatzgruppen trial at Nuremberg that he had seen Hitler's body being carried in a blanket as insufficient evidence of the dictator's death; this led to an extensive investigation and for new testimony to be taken.[39]

In 1956, Linge, Günsche, and Hitler's pilot Hans Baur were released from Soviet captivity and brought to Berlin. They were again torturously interrogated, with the goal of obtaining statements to prove the Soviet narrative that Hitler killed himself with poison. Remaining loyal to Hitler, Baur told the two others to "Never say what really happened."[40] Both Linge and Günsche stated that they saw a wound the size of a small coin on Hitler's right temple with a puddle on the floor;[41] contrarily, Linge stated in 1965 that the entry wound was to the left temple, but he subsequently recanted this.[5][42][43][lower-alpha 5] The discrepancies between eyewitnesses spurred a criminological report for West Germany officials, which contrasted Axmann and Linge's description of the suicide aftermath against Günsche's, the latter claiming that Hitler was sitting in a chair next to the sofa. Hitler's death certificate was registered in 1956 as an assumption of death on the basis that no eyewitnesses had seen his body—which Joachimsthaler points out is false.[44]

SS-Rottenführer Harry Mengershausen also made contradictory statements, initially claiming that Stumpfegger killed Hitler with a cyanide injection, but later claiming to have seen the temple entry wound.[45] Reichssicherheitsdienst (RSD) guard Hermann Karnau stated that before the cremation began Hitler's skull was "partially caved in and the face encrusted with blood".[31] Günsche said that by this time "the bloodstains from the temple had spread further over the face".[46][lower-alpha 5] RSD guards Erich Mansfeld and Karnau testified that the remains were reduced to something between charred bones and piles of ashes which fell apart to the touch.[47] Various witnesses and analyses agree that there was more than enough petrol to achieve extensive burning,[48] although Trevor-Roper opines that the bones would not likely have completely disintegrated due to the burning taking place in open air.[49] Hitler's chauffeur, Erich Kempka (who stated falsehoods and retracted many of his statements about the entire affair)[50][51] stated in June 1945 about the cremations, "I doubt if anything remained of the bodies. The fire was terrifically intense. Maybe some evidence like bits of bone and teeth could be found but the artillery shelling "scattered things all over."[14][18][lower-alpha 8][lower-alpha 6] Until 1968, Western historians referred to Hitler's mandibular remains without mentioning their fragmentary nature.[52][21]

Further findings

In 1946, the successor to the NKVD, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, conducted a second investigation (known as "Operation Myth"). Blood from Hitler's sofa and wall was reportedly matched to his blood type and a partially burnt skull fragment was found with gun damage to the posterior of the parietal bone.[53][54][lower-alpha 9] These two discoveries led to the Soviet admission that Hitler died by gunshot, as opposed to cyanide poisoning (as claimed by the purported autopsy report published in Bezymenski's book).[53][57]

.png.webp)

In 1963, author Cornelius Ryan interviewed General B. S. Telpuchovski, a Soviet historian who was allegedly present during the aftermath of the Battle of Berlin. Telpuchovski claimed that on 2 May 1945, a burnt body he thought belonged to Hitler was found wrapped in a blanket.[59][lower-alpha 10][lower-alpha 11] This supposed individual had been killed by a gunshot through the mouth, with an exit wound through the back of the head.[59][lower-alpha 4] Several dental bridges were purportedly found next to the body, because, Telpuchovski stated, "the force of the bullet had dislodged them from the mouth".[59][lower-alpha 6] According to Telpuchovski, a total of three burnt Hitler candidates had been produced, apparently including a body double wearing mended socks,[59] as well as an unburnt body.[60][lower-alpha 12]

Author

Soviet journalist Lev Bezymenski (1920–2007),[67] the son of poet Aleksandr Bezymensky, served as an interpreter in the Battle of Berlin under Marshal Zhukov.[68][69] Early on 1 May 1945, he translated a letter from Goebbels and Bormann announcing Hitler's death.[67][55] Bezymenski authored several works about the Nazi era.[67]

Content

The book begins with an overview of the Battle of Berlin and its aftermath, including a reproduction of the purported Soviet autopsy report of Hitler's body.[70] Bezymenski states that the bodies of Hitler and Braun were "the most seriously disfigured of all thirteen corpses" examined.[71] The appendix summarizes the discovery of the Goebbels family's corpses and includes further forensic reports.[72] On why the autopsy reports were not released earlier, Bezymenski says:

Not because of doubts as to the credibility of the experts. ... Those who were involved in the investigation remember that other considerations played a far larger role. First, it was resolved not to publish the results of the forensic-medical report but to "hold it in reserve" in case someone might try to slip into the role of "the Führer saved by a miracle." Secondly, it was resolved to continue the investigations in order to exclude any possibility of error or deliberate deception.[73]

The Death of Adolf Hitler

Early in the book, Bezymenski contends that accounts written by those who lacked access to the autopsy reports "have confused the issue rather than clarifying it."[74] He cites The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (1960), in which William L. Shirer states:

The bones were never found, and this gave rise to rumors after the war that Hitler had survived. But the separate interrogation of several eyewitnesses by British and American intelligence officers leaves no doubt about the matter. Kempka has given a plausible explanation as to why the charred remains were never found. "The traces were wiped out," he told his interrogators, "by the uninterrupted Russian artillery fire."[75]

Bezymenski goes on to cite Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962 edition), in which Alan Bullock says:

What happened to the ashes of the two burned bodies left in the Chancellery Garden has never been discovered. ... Trevor-Roper, who carried out a thorough investigation in 1945 of the circumstances surrounding Hitler's death, inclines to the view that the ashes were collected into a box and handed to Artur Axmann. ... It is, of course, true that no final incontrovertible evidence in the form of Hitler's dead body has been produced.[76]

Bezymenski then gives an account of the battle of Berlin, the subsequent investigation by SMERSH, supplemented by later statements of Nazi officers. Bezymenski quotes SMERSH commander Ivan Klimenko's account, which states that on the night of 3 May 1945, he witnessed Vizeadmiral Hans-Erich Voss seem to recognize a body as Hitler's in a dry water tank filled with other corpses outside the Führerbunker, before recanting this identification.[77] Klimenko noted that the corpse had mended socks, initially giving him doubt as well.[77] Klimenko then relates that on 4 May, Soviet Private Ivan Churakov found legs sticking out of the ground in a crater outside the Reich Chancellery.[lower-alpha 13] Two corpses were exhumed, but Klimenko had these reburied, thinking that the doppelgänger would be identified as Hitler. Only that day did several witnesses say it was definitely not Hitler's body, and a diplomat released it for burial. On the morning of 5 May, Klimenko had the other two bodies reexhumed.[79][lower-alpha 14] By 11 May, two colleagues of Hitler's dentist[lower-alpha 2] both confirmed the dental remains of Hitler and Eva Braun.[9] On 13 May, SMERSH produced a report of the initial disposal of the corpses based on the testimony of an SS guard.[81]

A report on the purported forensic examination of Hitler's body conducted on 8 May[lower-alpha 15] states that the "remains of a male corpse disfigured by fire[lower-alpha 16] were delivered in a wooden box[lower-alpha 17] ... On the body was found a piece of yellow jersey ... charred around the edges, resembling a knitted undervest."[84] The height of the body was judged to be about 1.65 metres (5 feet 5 inches).[65] (Hitler stood 1.76 m or 5 ft 9 in tall.)[85][86] Part of the skull was missing, as was the left foot[lower-alpha 18] and the left testicle.[89][lower-alpha 19] The upper dental remains consisted of nine upper teeth, mostly gold, with dental work connected by a gold bridge.[lower-alpha 20][lower-alpha 21] The lower jawbone fragment had 15 teeth, 10 of them apparently artificial;[lower-alpha 21] it was found loose in the oral cavity,[lower-alpha 22] and was broken and burnt around the alveolar process, the bulge that encases the tooth sockets.[65][lower-alpha 23] Splinters of glass and a "thin-walled ampule" were found in the mouth, apparently from a cyanide capsule,[93] which was ruled to be the cause of death.[57][lower-alpha 24] Soviet physician Faust Shkaravsky, who oversaw the alleged autopsy, declared that "No matter what is asserted ... our Commission could not detect any traces of a gun shot ... Hitler poisoned himself."[95]

Bezymenski also criticizes discrepancies of prior reports. Günsche allegedly told the Soviets in 1950 that both Hitler and Braun were seated on the sofa, but in 1960, said both were on chairs. Bezymenski points out that Linge's 1965 claim of Hitler's entry wound being to the left temple is unlikely as Hitler was right-handed and his left hand trembled significantly.[42]

Bezymenski quotes testimony given to the Soviets by SS general Johann Rattenhuber, in which he claimed that before killing himself with cyanide, Hitler ordered Linge to return in ten minutes to deliver a coup de grâce-style gunshot to ensure his death. Bezymenski calls it "certain" that if anyone shot Hitler, it was not himself. To support this claim, he cites the little black dog found nearby, which was killed in a similar fashion.[96] The author also refers to a skull fragment recovered in 1946, which had a gunshot wound to the back of the head, saying it most likely belonged to Hitler.[65][lower-alpha 9]

Bezymenski asserts that sometime after the forensic examinations, the corpses of Hitler and the others were completely burned and the ashes scattered.[73][lower-alpha 12]

Appendix

The appendix includes the purported Soviet forensic reports on the bodies of Braun, the Goebbels family, General Krebs, and two dogs.

Eva Braun

The purported autopsy of the body presumed to be Braun's was conducted on 8 May 1945. The corpse is noted as being "impossible to describe the features of", owing to its extensive charring. Almost the entire upper skull was missing. The occipital and temporal bones were fragmentary, as was the lower left of the face. The upper jaw contained four teeth,[lower-alpha 25] while the lower jaw had six teeth on the left; the others were missing—according to the report "probably because of burning". The alveolar process of the maxilla was also absent. A piece of gold (probably a filling) was found in the mouth cavity, and a gold bridge with two false molars was under the tongue. The woman was judged to be no more than middle-aged due to her teeth being only slightly worn; her height was approximately 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in). There was a splinter injury to the chest resulting in hemothorax, injuries to one lung and the pericardium—accompanied by six small metal fragments.[lower-alpha 26] Pieces of a glass ampule were found in the mouth, and the smell of bitter almonds which accompanies death from cyanide poisoning was present; this was ruled to be the cause of death.[98]

Goebbels family

The partly burnt body of Joseph Goebbels and the remains presumed to be Magda Goebbels were discovered near the bunker emergency exit by Ivan Klimenko on 2 May 1945, reportedly after a German notified him of their presence.[100] The next day, Senior Lieutenant Ilyin found the bodies of the Goebbels children in one of the rooms of the Chancellery bunker. The bodies were identified by Vizeadmiral Voss, cook Lange, and Karl Schneider (referred to as the head garage mechanic), "all of whom knew [the Goebbels family] well."[101] The autopsies of two of the children are listed as taking place on 7 and 8 May; all six children were determined to have died from cyanide poisoning.[102] Autopsies for Joseph, Magda and General Krebs were conducted on 9 May.[103]

Joseph Goebbels's body was "heavily scorched", but was identified by his size, estimated age, shortened right leg and related orthopedic appliance, as well as his head characteristics and dental remains, which included many fillings. His genitals were "greatly reduced in size, shrunken, dry." Chemical testing revealed cyanide compounds in the internal organs and blood; cyanide poisoning was judged to be the cause of death.[104]

The body presumed to be Magda's was scorched beyond recognition. Voss identified two items found on the corpse as having been in her possession: a cigarette case inscribed "Adolf Hitler—29.X.34", which she had used for the last three weeks of her life, and Hitler's Golden Party Badge, which the dictator had given her three days before his suicide.[105][106] Additionally, a reddish-blond hairpiece was identified as matching the color of one Magda wore. Her dental remains, including both a maxilla and mandible with dental work, were found loose on the corpse along with splinters from a thin-walled ampule; the cause of death was ruled to be cyanide poisoning.[105]

General Krebs

General Krebs is erroneously listed in the autopsy report as "Major General Krips" (as Bezymenski notes). Cyanide compounds were detected in the internal organs and the smell of bitter almonds was recorded, leading the commission to conclude that Krebs' death was "obviously caused by poisoning with cyanide compounds." Three light head wounds were presumed to have been obtained from his death fall onto a protruding object.[107]

Dogs

A German Shepherd matching Hitler's dog Blondi's description appears to have died from cyanide poisoning.[108] A small black bitch, about 60 centimetres (2 ft) long and 28 cm (1 ft) tall, was poisoned by cyanide before being shot in the head.[109]

Photographs

Sixteen pages of previously unreleased photographs[110] include those of Ivan Klimenko, head of autopsy commission Faust Shkaravsky, the locations of Hitler's burning and burying site outside the Führerbunker's emergency exit, SMERSH agents exhuming Hitler and Braun's remains, a diagram of where the corpses of Hitler, Braun, Joseph and Magda Goebbels were burned, Hitler and Braun's alleged corpses in boxes[lower-alpha 17] (angled so that unidentifiable mounds of flesh can be seen), front and back views of Hitler's golden upper dental bridge and a lower jawbone fragment connecting his lower teeth and bridges, a sketch drawn by Hitler's dentist's assistant Käthe Heusermann on 11 May 1945 to identify Hitler's dental remains, Braun's dental bridge, the first and last page of Hitler's autopsy report, the Soviet autopsy commission with both Kreb's and Joseph Goebbels' corpses, the bodies of the Goebbels family, the bodies of Krebs and the Goebbels children at Plötzensee Prison,[111] and Blondi's corpse.[112]

Criticism and legacy

Upon the book's publication, Hugh Trevor-Roper wrote that it was "remarkable that [Bezymenski's] book is apparently for Western consumption only", with no Russian release and the book's original language apparently being German. Trevor-Roper says, "No explanation is offered of these interesting facts, which suggest a propagandist rather than an historical purpose."[68] A paperback edition was published in English in 1969, claiming on the cover to "prove how Hitler died ... for the first time".[113] In his 1971 book about Hitler, German historian Werner Maser expresses doubt about Bezymenski's book, including the autopsy's insinuation that Hitler had only one testicle.[114][lower-alpha 19]

In 1972, forensic odontologists Reidar F. Sognnaes and Ferdinand Strøm reconfirmed Hitler's dental remains based on X-rays of Hitler taken in 1944, the 1945 testimony of Käthe Heusermann and dental technician Fritz Echtmann, as well as the purported Soviet forensic examination of the dental remains.[115] Soviet war interpreter Elena Rzhevskaya claimed to have seen Hitler's charred corpse in the Chancellery garden. According to her, the dental remains were removed during the alleged autopsy (at which Bezymenski asserts she was not present),[116] and the pages of the report about them were recorded on "two large non-standard sheets of paper".[62] Rzhevskaya safeguarded the dental remains until they could be identified by Hitler's dental staff. Shkaravsky (d. 1975) wrote to her that the commission had been forbidden to photograph Hitler's body for unknown reasons and suggested that the damage to Braun's chest could have been from shrapnel.[62] According to Lindloff, who cremated Hitler and Braun's bodies, after only 30 minutes the bodies were "already charred and torn open", in part caused by shrapnel.[117]

.jpg.webp)

In his 1975 book The Bunker, journalist James P. O'Donnell dismisses the book's implication that a poisoned Hitler could not have shot himself, pointing out that "few if any poisons act instantly, [and] certainly not cyanide".[118][119] O'Donnell dismisses the supporting claim that Hitler would not have been able to pull the trigger due to hand tremors, as only his left hand shook badly. O'Donnell further exhorts: "Hitler lacked many human qualities; but, really, did he lack a strong will?"[118]

In 1978, Jove Books published an English-language mass-market paperback, which incorporates an Operation Cornflakes stamp on the cover.[113] In 1982, a second edition of the book was released in German.[120] This included the odontological report by Sognnaes and Strøm.[121] Additionally, Bezymenski attempts to account for the failure to produce evidence of Hitler's death by gunshot.[114] He also expounds on Mengershausen's claims, saying that he was extensively interrogated by the Soviets as a key witness, in June 1945 providing the exact locations where he supposedly buried Hitler and Braun.[122][21]

In 1992, Bezymenski wrote that Hitler's corpse was cremated in April 1978, despite asserting in 1968 that it had already been done.[123][lower-alpha 12] A 1992 Der Spiegel article claims that Bezymenski had now learned that the cremation took place in 1970.[124] The article further asserts that the blood type was not determined in 1946 (contrary to contradictory Soviet and U.S. claims) and that during the 1946 investigation, the Soviets found trickle-like bloodstains on Hitler's sofa, interpreted by Der Spiegel as implying Hitler died slowly. Bezymenski, who described himself as having been "a product of the era and a typical party propagandist", stated that "It is not difficult to guess why the KGB [did not give me findings suggesting Hitler's slow death, as I] was supposed to lead the reader to the conclusion that all talk of a gunshot was a pipe dream or half an invention and that Hitler actually poisoned himself."[124] In a 2003 episode of National Geographic's Riddles of the Dead, Bezymenski elaborates that the KGB only granted him access to the documents in the Soviet archive on the basis that he would maintain the narrative that Hitler died by cyanide and say his remains had been cremated by June 1945.[55]

In 1995, journalist Ada Petrova and historian Peter Watson wrote that they considered Bezymenski's account at odds with Trevor-Roper's report, published as The Last Days of Hitler (1947).[125] Though Petrova and Watson used Bezymenski's book as a source for theirs,[126] they note issues with the SMERSH investigation.[94] A main issue they cite is that the autopsies on the alleged remains of Hitler and Braun did not include a record of dissection of their internal organs, which would have shown with certainty whether poison was a factor in their deaths.[94] They also opine that it was dissatisfaction of this first investigation, along with concerns of the findings of Trevor-Roper, that led to Stalin ordering a second commission in 1946.[127] Petrova and Watson also cite Hitler's alleged autopsy report to refute Hugh Thomas's theory that only Hitler's dental remains belonged to him, saying that the entire jawbone structure[lower-alpha 6] would have had to have been found loose on the alleged body while clamping down on the tongue, which "would presumably be a very difficult arrangement to fake".[128][lower-alpha 22]

In 1995, Joachimsthaler criticized Bezymenski's account in his book on Hitler's death, reaching the same conclusion put forward 45 years earlier by U.S. jurist Michael Musmanno (presiding judge at the Einsatzgruppen trial) that the dictator's corpse was almost completely burned to ashes[lower-alpha 8]—meaning that no body would have remained to perform an autopsy on. Joachimsthaler implies that another body must have been examined instead, while also pointing out that hydrogen cyanide would have been evaporated by the fire and thus not left an odor. He quotes German pathologist Otto Prokop as saying about the alleged autopsy: "Bezemensky's report is ridiculous. ... Any one of my assistants would have done better ... the whole thing is a farce ... it is intolerably bad work ... the transcript of the post-mortem section of 8 [May] 1945 describes anything but Hitler."[129] Similarly, historian Luke Daly-Groves states that "the Soviet soldiers picked up whatever mush they could find in front of Hitler's bunker exit, put it in a box and claimed it was the corpses of Adolf and Eva Hitler", and also denounces "the dubious autopsy report riddled with scientific inconsistencies and tainted by ideological motivations".[130] Only the report's coverage of the dental remains has been substantially verified, with 2017–2018 analysis led by French forensic pathologist Philippe Charlier concluding that the extant evidence "[fits] perfectly" with the Soviet description.[66] Contradicting previous accounts of the finding of the dental remains, Joachimsthaler asserts that the Soviets sifted them from the dirt in the manner Heimlich claimed without evidence that the Americans searched the garden in December 1945, implying that Heimlich learned of this method from a Soviet officer and incorporated it into his account.[131][132]

In their addendum to The Hitler Book (2005), Henrik Eberle and Matthias Uhl quote Bezymenski as admitting in 1995 that his work included "deliberate lies" and criticize his book for advocating the theories that Hitler died by poisoning or a coup de grâce.[133] Despite this, in 2018, investigative journalists Jean-Christophe Brisard and Lana Parshina asserted that Hitler could have commissioned Linge to shoot him through the temples because the dictator's poor health—particularly his hand tremors—would have made it difficult for him to do.[40] However, Brisard and Parshina also dismiss Bezymenski's book as largely propagandistic.[85]

See also

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 Initially released in German as Der Tod des Adolf Hitler: Unbekannte Dokumente aus Moskauer Archiven, the 1982 German second edition was re-subtitled Der sowjetische Beitrag über das Ende des Dritten Reiches und seines Diktators (lit. 'The Soviet Contribution to the End of the Third Reich and Its Dictator').[1]

- 1 2 Dental assistant Käthe Heusermann helped locate Hitler's X-rays and directed the Soviets to dental technician Fritz Echtmann, who had made Hitler's bridges.[9]

- ↑ Axmann evaded Soviet capture but was arrested by the U.S. Army in December 1945.[23] Linge and Günsche were captured by the Soviets and spent a decade in captivity, undergoing extensive questioning under torturous conditions.[24]

- 1 2 Two of the three eyewitnesses to the immediate aftermath of Hitler's suicide said he did not die by a gunshot through the mouth and none reported seeing a wound in the back of his head.[63] Further, in 2017–2018, forensic analysis was conducted on Hitler's dental remains, which did not detect any gunpowder.[64]

- 1 2 3 Additionally, after the body was wrapped in a blanket, SS-Hauptsturmführer Karl Schneider purportedly saw coagulated blood on both temples and SS-Rottenführer Harry Mengershausen reputedly saw an entry wound on Hitler's right temple.[33][34] Anton Joachimsthaler theorizes that the bullet, fired more or less at contact range from a Walther PP or PPK, could have passed through one temple and become lodged inside the other, causing subcutaneous bleeding; he cites the apparent lack of a bullet or a bullet hole in the wall, as well as the statistical possibility (according to a 1925 study) of 7.65-mm bullets fired from pistols at living persons becoming lodged.[35]

- 1 2 3 4 In addition to a maxillar golden bridge, Hitler's dental remains include a mandibular fragment broken around the alveolar process.[65][66]

- ↑ Axmann also stated both that he saw no blood coming from Hitler's mouth[31][36] and that the mouth "was bloody and smeared".[37] Additionally, Axmann said Günsche told him that Hitler had taken poison then shot himself;[32][31] Günsche later denied telling Axmann that Hitler took poison.[22]

- 1 2 In his 1950 book about Hitler's death, U.S. jurist Michael Musmanno argues that "there never was any authoritative account that Hitler's and Eva Braun's bodies were found intact."[17]

- 1 2 In 2003, forensic anthropologist Marilyn London argued that internal trauma caused by the gunshot could have facilitated the detachment of the skull fragment.[55] In 2009, DNA and forensic tests indicated that it belonged to a woman less than 40 years old.[56]

- ↑ In his 1966 book, The Last Battle, Ryan describes this body as being Hitler's, saying it had been buried "under a thin layer of earth".[60]

- ↑ According to Soviet war interpreter Elena Rzhevskaya, this is the day Joseph Goebbels and a woman presumed to be his wife[61] were discovered, but Hitler's body was not unearthed until 4 May.[62]

- 1 2 3 Soviets also told Cornelius Ryan in 1963 that Hitler's body had by that time been cremated.[59]

- ↑ Later in the book, Bezymenski credits Churakov with "[pulling] the dreadfully disfigured corpse of Adolf Hitler from the rubble", though Klimenko describes the exhumation as a group effort.[78]

- ↑ A 2005 book containing previously unpublished KGB files includes a Soviet field report dated 5 May 1945 about the retrieval of a pair of "badly burnt" bodies, male and female, corroborating the date.[80]

- ↑ Bezymenski explains that the initial report was handwritten. Because it was typewritten at a later date, the 11 May identification of the dental remains by Blaschke's assistant Käthe Heusermann is mentioned.[82]

- ↑ The autopsy report states that "On the face and body the skin is completely missing; only remnants of charred muscles are preserved."[65] In the 2017–2018 analysis of Hitler's remains led by French forensic pathologist Philippe Charlier, it was pointed out that muscles remain near the areas of the jawbone fragment affected by burning.[54]

- 1 2 The boxes containing the remains of Hitler and Braun were ammunition crates.[83]

- ↑ Karnau claimed that "the flesh on the lower parts of [Hitler's body] had burned away, and [his] shinbones were visible."[87] Additionally, Mengershausen, who claimed to have reidentified Hitler's remains in July 1945, stated that "The feet had been entirely consumed."[21][88]

- 1 2 Bezymenski says that "This congenital defect [of a missing testicle] had not been mentioned anywhere in the existing literature. But Professor Karl von Hasselbach, one of Hitler's physicians, remembers that the Führer always refused categorically to have a medical check-up."[90] Historian Sjoerd de Boer opined that the story of only having one testicle suited Stalin's desire to portray Hitler as a coward who died by either poison or a coup de grâce.[91]

- ↑ The autopsy report notes that "the right canine tooth is fully capped by [gold]."[65] According to Bezymenski, Käthe Heusermann (assistant to Hitler's dentist, Hugo Blaschke) identified traces of where it had been sawn through by Blaschke in 1944.[90]

- 1 2 Charlier et al. 2018 describes a number of upper and lower teeth as conglomerates of natural and artificial elements.

- 1 2 Despite the lower jawbone fragment being unattached to flesh, the tip of the burnt tongue is claimed to have been "locked between the teeth of the upper and lower jaws."[65]

- ↑ The dental remains were subsequently stored at the KGB's headquarters.[92] By 2017, the jawbone fragment had separated into three pieces and Philippe Charlier confirmed the Soviet description.[66]

- ↑ Petrova and Watson point out that no dissection of internal organs was recorded, making this impossible to verify.[94]

- ↑ These comprised three molars and a loose canine, in addition to a detached root.[97]

- ↑ Bezymenski attributes this to splinters from Soviet shelling while the bodies were burning in the garden.[71]

Citations

- ↑ Jaeger, Stephan (2009). "The Atmosphere in the 'Führerbunker.' How to Represent the Last Days of World War II". Monatshefte. 101 (2): 229–244 (242). doi:10.1353/mon.0.0115. ISSN 0026-9271. JSTOR 20622190. S2CID 162188389.

- ↑ Beevor, Antony (2002). Berlin – The Downfall 1945. New York: Viking-Penguin. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-670-03041-5.

- ↑ O'Donnell 2001, pp. 230, 323.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 951–952. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

- 1 2 Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 154–155.

- ↑ Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 1137–1138. ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.

- ↑ Mitchell, Arthur (2007). Hitler's Mountain: The Führer, Obersalzberg and the American Occupation of Berchtesgaden. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-7864-2458-0.

- ↑ "HITLER BODY FOUND, RUSSIANS REPORT; Servant, However, Challenges Identity, Declaring Corpse That of a 'Cook Double'". The New York Times. 9 May 1945. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 Bezymenski 1968, pp. 47–48, 53–55.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 99, 207, 299, 303.

- ↑ Trevor-Roper 2002, p. liv.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 22, 23, 247–249.

- ↑ "World War II // 50 Years Ago Today". Tampa Bay Times. 6 July 2006. Retrieved 16 August 2022.

- 1 2 "International: Where There's Smoke ..." Time. 2 July 1945. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ↑ Beschloss, Michael (December 2002). "Dividing the Spoils". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ↑ Philpot, Robert (2 May 2019). "'Hitler lived': Scholar explores the conspiracies that just won't die". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 27 April 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- 1 2 Musmanno 1950, p. 233.

- 1 2 Bradsher, Greg (17 December 2015). "Hunting Hitler Part VII: The Search Continues, June-September 1945". The Text Message. Retrieved 8 August 2022 – via the National Archives and Records Administration.

- ↑ Miller, Merle (10 August 1945). "Berlin Today". Yank, the Army Weekly. United States Department of War. 4 (8): 7.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (2001) [2000]. Hitler, 1936–1945: Nemesis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 1038. ISBN 0-393-04994-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Trevor-Roper 2002, p. xliii.

- 1 2 3 Joachimsthaler 2000, p. 158.

- 1 2 Hamilton, Charles (1984). Leaders & Personalities of the Third Reich, Vol. 1. San Jose, CA: R. James Bender Publishing. p. 248. ISBN 0-912138-27-0.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 258–259, 281, 283.

- ↑ Vinogradov, Pogonyi & Teptzov 2005, pp. 160–164.

- ↑ Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1 February 1951). "Is Hitler Really Dead? A Historian Examines the Evidence". Commentary. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, p. 159.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 154–156.

- ↑ Rising, David (24 April 2005). "Hitler's Final Days Described by Bodyguard". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ↑ Henry, Martin (2016). "Europe's Dark Past: The Case of Rochus Misch". Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. 105 (419): 353–361. ISSN 0039-3495.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Axmann, Artur, interviewed on January 7, 1948 and January 9, 1948. - Musmanno Collection -- Interrogations of Hitler Associates". Gumberg Library Digital Collections. Retrieved 8 October 2021 – via Duquesne University.

- 1 2 3 Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 155–158.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 160–161, 292.

- ↑ Trevor-Roper 2002, p. lvi.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 161–164, 166, 302.

- 1 2 Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 156, 158.

- 1 2 "Axmann, Artur, interviewed on October 10, 1947. - Musmanno Collection -- Interrogations of Hitler Associates". Gumberg Library Digital Collections. Retrieved 8 October 2021 – via Duquesne University.

- ↑ "Axmann, Artur, interviewed on October 10, 1947. - Musmanno Collection -- Interrogations of Hitler Associates". Gumberg Library Digital Collections. Retrieved 8 October 2021 – via Duquesne University.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 8–13, 159–160.

- 1 2 O'Malley, J. P. (4 September 2018). "Putin grants authors partial access to secret Soviet archives on Hitler's death". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 155–156.

- 1 2 Bezymenski 1968, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Linge 2009, pp. 199–201.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 8–13, 159–161.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, p. 160.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, p. 193.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 210–215, 292–293.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 210–215.

- ↑ Trevor-Roper 2002, p. 182.

- ↑ Knauth, Percy (23 July 1945). "Did Adolf and Eva Die Here?". Life. Vol. 19, no. 4. p. 27.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 147–148, 164–165.

- ↑ Musmanno 1950, pp. 231, 233.

- 1 2 Petrova & Watson 1995, pp. 81–82, 84–86.

- 1 2 Charlier et al. 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Hitler's Skull". Riddles of the Dead. 2003. 12:30, 14, 19, 28:30 minutes in. National Geographic.

- ↑ ABC News (9 December 2009). "DNA Test Sparks Controversy Over Hitler's Remains". ABC News. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- 1 2 Bezymenski 1968, p. 49.

- ↑ Petrova & Watson 1995, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "3 Dead Hitlers a Puzzle". The San Francisco Examiner. San Francisco, CA. 16 March 1966. p. 72. Retrieved 23 July 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Ryan 1995, pp. 504–505.

- ↑ Ryan 1995, p. 366.

- 1 2 3 Rzhevskaya, Yelena (2018) [2012]. Memoirs of a Wartime Interpreter: From the Battle of Rzhev to the Discovery of Hitler's Berlin Bunker. Translated by Tait, Arch. Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1784382810.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 158, 166.

- ↑ Daley, Jason (22 May 2018). "Hitler's Teeth Confirm He Died in 1945". Smithsonian. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bezymenski 1968, p. 45.

- 1 2 3 Charlier et al. 2018. "It is important to see that these data fit perfectly with the [Soviet] autopsy report and with our direct observations."

- 1 2 3 "Lev Bezymenskii". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- 1 2 Trevor-Roper, Hugh (26 September 1968). "Hitler's Last Minute". The New York Review of Books.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 44–50.

- 1 2 Bezymenski 1968, p. 51.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 3–76, 79–82, 85–114.

- 1 2 Bezymenski 1968, p. 66.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, p. 4.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 4–5.

- 1 2 Bezymenski 1968, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 33, 76.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Vinogradov, Pogonyi & Teptzov 2005, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 35–37.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 44, 47–48.

- ↑ Petrova & Watson 1995, p. 54.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, p. 44.

- 1 2 Brisard & Parshina 2018.

- ↑ Flood, Charles Bracelen (1985). "Lance Corporal Adolf Hitler on the Western Front, 1914–1918". The Kentucky Review. University of Kentucky. 5 (3): 4.

- ↑ Musmanno 1950, p. 221.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, p. 223.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 46–47.

- 1 2 Petrova & Watson 1995, p. 57.

- ↑ de Boer 2022, p. 183.

- ↑ Beevor, Antony (11 October 2009). "Opinion | Hitler's Jaws of Death". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ↑ Marchetti, Daniela; Boschi, Ilaria; Polacco, Matteo; Rainio, Juha (2005). "The Death of Adolf Hitler—Forensic Aspects". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 50 (5): 1147–1153. doi:10.1520/JFS2004314. PMID 16225223. JFS2004314.

- 1 2 3 Petrova & Watson 1995, p. 81.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 58, 75.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 73–75.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, p. 111.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 110–114.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, p. 51.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 30, 102.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 85, 91, 107.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 94, 99, 103.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 95–99.

- 1 2 Bezymenski 1968, pp. 81–82, 99–103.

- ↑ Angolia, John (1989). For Führer and Fatherland: Political & Civil Awards of the Third Reich. R. James Bender Publishing. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-912-13816-9.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 103–107.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 89–90, 92.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, pp. 92–94.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, inside jacket.

- ↑ Erickson, John (2015). The Road to Berlin. Orion Publishing Group. p. 435. ISBN 9781474602808.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, index of illustrations.

- 1 2 3 "The Death of Adolf Hitler by Lev Bezymenski, First Edition". AbeBooks. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- 1 2 Raack, R. C. (1991). "With Smersh in Berlin: New Light on the Incomplete Histories of the Führer and the Vozhd'". World Affairs. 154 (2): 47–55. ISSN 0043-8200. JSTOR 20672302.

- ↑ Senn, David R.; Weems, Richard A. (2013). Manual of Forensic Odontology. Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-439-85134-0.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, p. 69.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, p. 212.

- 1 2 O'Donnell 2001, pp. 322–323.

- ↑ Bezymenski 1968, p. 72.

- ↑ Eberle & Uhl 2005, p. 341.

- ↑ "Der Tod des Adolf Hitler : der sowjetische Beitrag über das Ende des Dritten Reiches und seines Diktators / Lew Besymenski ; [aus dem Russischen übersetzt von Valerie B. Danilow]". UCLA Library. Retrieved 17 August 2022.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 203–204.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, p. 253.

- 1 2 "Hitlers letzte Reise". Der Spiegel (in German). 19 July 1992. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ Petrova & Watson 1995, p. 162.

- ↑ Gimbert, Robert A. (1996). "The Death of Hitler: The Full Story with New Evidence from Secret Russian Archives". Military Review. US Army Command and General Staff College: 93.

- ↑ Petrova & Watson 1995, pp. 81–82, 84–85.

- ↑ Petrova & Watson 1995, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 174, 252–253.

- ↑ Daly-Groves 2019, p. 157.

- ↑ Joachimsthaler 2000, pp. 28–29, 284 n.21.

- ↑ Musmanno 1950, pp. 233–234.

- ↑ Eberle & Uhl 2005, pp. 287–288, 341.

Sources

- Bezymenski, Lev (1968). The Death of Adolf Hitler (1st ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Brisard, Jean-Christophe and Parshina, Lana (2018). The Death of Hitler. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306922589.

- Charlier, Philippe; Weil, Raphael; Rainsard, P.; Poupon, Joël; Brisard, J.C. (1 May 2018). "The remains of Adolf Hitler: A biomedical analysis and definitive identification". European Journal of Internal Medicine. 54: e10–e12. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2018.05.014. PMID 29779904. S2CID 29159362.

- Daly-Groves, Luke (2019). Hitler's Death: The Case Against Conspiracy. Oxford, UK: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-4728-3454-6.

- de Boer, Sjoerd (2022). The Hitler Myths: Exposing the Truth Behind the Stories about the Führer. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-39901-905-7.

- Eberle, Henrik; Uhl, Matthias, eds. (2005). The Hitler Book: The Secret Dossier Prepared for Stalin from the Interrogations of Hitler's Personal Aides. New York: Public Affairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-366-1.

- Joachimsthaler, Anton (2000) [1995]. The Last Days of Hitler: The Legends, The Evidence, The Truth. Translated by Helmut Bölger. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-1-85409-465-0.

- Linge, Heinz (2009) [1980]. With Hitler to the End. Translated by Brooks, Geoffrey (1st English ed.). Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60239-804-7.

- Musmanno, Michael A. (1950). Ten Days to Die. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- O'Donnell, James P. (2001) [1978]. The Bunker. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80958-3. German: [1975]

- Petrova, Ada; Watson, Peter (1995). The Death of Hitler: The Full Story with New Evidence from Secret Russian Archives. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-03914-6.

- Ryan, Cornelius (1995) [1966]. The Last Battle. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-80329-6.

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh (2002) [1947]. The Last Days of Hitler (7th ed.). London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-49060-3.

- Vinogradov, V. K.; Pogonyi, J. F.; Teptzov, N. V. (2005). Hitler's Death: Russia's Last Great Secret from the Files of the KGB. Chaucer Press. ISBN 978-1-904449-13-3.

Further reading

- Sognnaes, Reidar F.; Ström, Ferdinand (1973). "The odontological identification of Adolf Hitler". Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 31 (1): 43–69. doi:10.3109/00016357309004612. PMID 4575430.

.jpg.webp)