Teraina in October 2006. North is on top. Notice the lake covering the southeast region of the island. The prevailing ocean current runs roughly left to right. | |

Teraina Washington Island  Teraina Washington Island  Teraina Washington Island  Teraina Washington Island | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | North Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 4°41′00″N 160°22′40″W / 4.68333°N 160.37778°W |

| Total islands | 1 |

| Area | 14.2 km2 (5.5 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Island council | Teraina |

| Largest settlement | Tangkore |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 1,893 (2020) |

| Pop. density | 120.6/km2 (312.4/sq mi) |

| Languages | Gilbertese |

| Ethnic groups | I-Kiribati |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

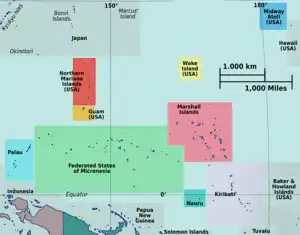

Teraina (written also Teeraina,[1] also known as Washington Island – these two names are constitutional[2]) is a coral atoll in the central Pacific Ocean and part of the Northern Line Islands which belong to Kiribati. Obsolete names of Teraina are New Marquesas, Prospect Island, and New York Island. The island is located approximately 4.71° North latitude and 160.76° West longitude. Teraina differs from most other atolls in the world in that it has a large freshwater lake (Washington Lake), an open lens, concealed within its luxuriant coconut palm forest; this is the only permanent freshwater lake in the whole of Kiribati.[3]

Measuring about 5.4 by 2.1 kilometres (3.4 by 1.3 miles) NW-SE and SW-NE, it has a land area of about 9.55 square kilometres (3.69 square miles);[3] its circumference is about 15 km (9 mi). The island is generally low-lying, with a maximum elevation ASL of about 5 meters (16 feet), while most of the island rises some three metres (10 feet) high; trees in the dense inland forest grow to several times this height however.[1] At the western end of the island is the capital, Tangkore (or Tengkore). There are (as at the 2020 Census) about 1,893 inhabitants,[1] making it the least-populated of the permanently inhabited Northern Line Islands. However, population density (177 per km2)[1] is three times as high as on Tabuaeran[1] and vastly more than on the much larger (300-plus km2) Kiritimati with its about 15 people/km2.[4]

There are two dirt roads around the island's perimeter – an outer (Beach Road) and an inner one (Ring Road). Transport inland is done by boat on artificial canals, rather uniquely for a Pacific island. A 21 meters (69 feet) navigation light tower and two radio masts stand near Tangkore.[5] What cannot be produced locally is shipped in about twice a year;[5] there is also some minor inter-island traffic by ship or boat. The old landing was at the western tip, but this was dangerous due to being exposed to surf breaking on the reef flats; it has been more recently replaced by a new and more easily accessible landing south of Tangkore, where the canal system feeds into the ocean.[5] A rough airstrip of some 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) length exists near Kaaitara. It may become temporarily unusable after heavy rains.

History

Permanent early human occupation of Teraina is disputed. Although there were no occupants on the island at the time of European discovery, a number of human made sites have been identified on the island including dry stacked stone architecture. Additionally, ethnographic data from the Cook Islands and the Tuamotu Islands points to Polynesian knowledge of the island. Perhaps the most compelling discovery on Teraina is the recovery of an intact voyaging canoe.[6] Although archaeological sites are known to exist on the island, the general lack of fresh water makes long-term human habitation unlikely though more work is needed in establishing the timeline of human use.

Teraina was sighted on 12 June 1798 by the American whaling captain Edmund Fanning of Betsy; he named the island for George Washington but did not attempt to land. The first exploration of the island arrived later with captain Adam Johann von Krusenstern, on a Russian expedition (called then New Marquesas).[7] The island was subsequently claimed under the Guano Islands Act of 1856 for the United States under the name "Prospect Island".[8] Guano was never mined or exported to any notable extent, however; the humid climate prevents the formation of substantial deposits. It was occupied by Captain John English and people from Manihiki in about 1860.

Later William Greig who began planting the island with coconut trees.[9] Eventually the sons of Greig owned the plantation with Father Emmanuel Rougier until he sold his interest to the Fanning Island Limited, and started a coconut plantation on Christmas Island.[9]

Fanning Island was annexed by the British by Commander Nichols of HMS Cormorant on May 29, 1889. It became a part of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony in 1916. The name of the island was changed to Teraina in 1979 when Kiribati gained independence.[1] The major export of Teraina is copra, the dried meat of the coconut.

The Burns Philip Copra Company operated plantations on the island after the Second World War.[1] At various times, contract laborers were brought from Manihiki, Tahiti, and the Gilbert Islands to work the coconut plantations.[5] More recently, settlement from Gilbert group has been encouraged during the re-settlement schemes of 1989–1995.[1]

Washington Island Post Office opened on 1 February 1921, closed around 1923, reopened in 1924, closed in 1948 and reopened again around August 1979.[10]

Political geography

| No. | Village | Population (2010 census[1]) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abaiang | 146 |

| 2 | Kauamwemwe | 198 |

| 3 | Uteute | 141 |

| 4 | Kaaitara | 0 |

| 5 | Tangkore | 410 |

| 6 | Matanibike | 91 |

| 7 | Arabata | 353 |

| 8 | Mwakeitari | 177 |

| 9 | Onauea | 174 |

| Teraina | 1690 | |

The population of Teraina lives in nine villages. It is increasing; from 416 in 1978, it had risen to 936 in 1990 and had exceeded 1,000 by 2000. The population of Teraina in the 2010 census was 1,690. Compared to the 2005 population of 1,155 and the 2000 population of 1,087, the population is growing very rapidly. The population of Teraina grew by 535 people between 2005 and 2010, an annual population growth of 7.9%.[1]

All villages are listed in the following table, with the preliminary census results of 2005, counterclockwise around the perimeter of the atoll, starting in the northeast with Abaiang and ending in the southeast with Onauea. Tangkore is near the westernmost point of Teraina:

Teraina has an unusual age structure; nearly half the population (44%) is aged under 15 and one in five people (19%) are children under five years. There are more males than females in almost all age groups except the elderly.[1]

Physical geography

As regards its physical characteristics, this is one of the most interesting islands in the Pacific. It is a raised coral atoll, but it has not filled up with sand and soil, yet still retains a significant remnant of the former lagoon. The lake, however, is only just barely perceptibly brackish, as its only significant source is the plentiful rain. The lake is only a few feet (around 1–2 meters) deep for the most part, though the supposed maximum depth is nearly 10 meters (33 feet). Being only about 520 km (320 mi; 280 nmi) away from the equator, Teeraina is inside the ITCZ; its climate is thus extremely humid, making it one of the "wet" Pacific islands.[12]

The western inland is made up by peat bog, which is still flooded after heavy rains,[13] and constitutes infilled former lakebed. It is not clear in what way the western lake or lakes – there are now 2 main areas of bogland, which may correspond to former lake basins – were connected to the remaining waterbody.[13] One bog is immediately adjacent to the lake's western end, the other is halfway between that and the island's northwest tip. Canals have been cut into the bogs, for punting, rowing and motor boats transporting people and produce. There is some removal of peat and sediments to stem the lake's ongoing infilling; in addition it seems that in recent times, the lake's level is slowly rising again so that the eastern bog's area has receded somewhat. The peat reaches thicknesses of about 1–1.5 meters (3.3–4.9 ft), much of which is located above sea level.[5]

It is also not precisely known where the last connection of the inland waters to the ocean were, and when they closed. The southeast end is more likely however, as the island is in the Equatorial Counter Current which runs west to east, and drifting coral and other reef-builder larvae as well as flotsam would therefore predominantly land at the island's western side.[5] Thus, it is to be expected that land build up faster there. This also agrees with the eastern location of the remaining lake. In any case, the canal network now opens to the sea south of Tangkore, and there is a direct connection from the lake to the ocean at Teraina's eastern tip.[14]

Ecology

Ecologically, Teraina is also highly interesting, for several reasons. First, as is readily apparent from its peculiar geographical and geological features, it possesses a combination of ecosystems that is quite unique in the entire world. Second, it holds the world's largest population of a rare bird species though it is over 2,500 km (1,600 mi; 1,300 nmi) from that bird's original home. Furthermore, it was until fairly recently home to some enigmatic dabbling ducks which are now extinct. Last, the island's biodiversity seems to prove quite conclusively that, probably by about 1200 AD or so, the island was temporarily inhabited by a significant number of humans.

At present, there is no formal protection for the islands' ecosystems or species, but it has been suggested to legally protect key habitat, namely the boglands.[3] Though it is globally endangered, the Rimatara lorikeet (Vini kuhlii) does not appear to be in need of formal protection;[15] it actually benefits from human land use change and the feral cats. The former provides the birds with more habitat, while the cats have so far managed to keep Teraina completely free of black rats (Rattus rattus) which due to their tree-climbing habits would seriously jeopardize the species' existence, should they become established in numbers.[15] Given the negative experience e.g. from Rennell Island, maintenance of a vigorous tilapia fishery would seem to be advisable. These fish certainly represent a valuable source of protein on Teraina, and in fact were originally introduced for that purpose.

Flora

Over 30 species of flowering plants are known from the island, but most seem to be not originally native. Cocos nucifera, the coconut palm, is the most conspicuous tree on Teraina. It is found planted, but also constitutes one of the dominant forest trees. The palms occur in wet forest around the bogs, mixed with Pandanus (screwpine), and an undergrowth dominated by the ferns Asplenium pacificum and Phymatosorus scolopendria. In more elevated places near the beach, Pisonia (catchbird tree) atoll forest is found, though Teraina has not that much of this ubiquitous Pacific ecosystem for its size.[3]

The most conspicuous plants of the boglands are the arum Cyrtosperma merkusii and the giant bulrush (Schoenoplectus californicus).[3]

Among the local crops, sugar-apple (Annona squamosa), breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis), papaya (Carica papaya), bananas (Musa cultivars, including Fe'i bananas[16]) and apple guava (Psidium guajava) are the most significant, apart from the coconuts. Frangipani (Plumeria) and hibiscus are popular as ornamental plants.[5]

Birds

Though numerous seabirds nest on Teraina, for many such species the limited habitat makes it a less important rookery than other, similar-sized raised atolls. About 10 species of seabirds breed here, most significantly tree-nesters like the little white tern (Gygis microrhyncha) and the red-footed booby (Sula sula).[3] The eastern reef egret (Egretta sacra), widespread throughout the region, can also be found on Teraina.

Among migratory birds, the ruddy turnstone (Arenaria interpres), sanderling (Calidris alba), bristle-thighed curlew (Numenius tahitiensis), Pacific golden plover (Pluvialis fulva), and grey-tailed (Tringa brevipes) and wandering tattlers (T. incana) use Teraina as stopover location or winter quarters on a regular basis. Other shorebirds, gulls, and occasionally ducks of North American and East Asian species may occur as vagrants.

In historic times, two species of landbirds and one subspecies of duck have been recorded. The latter, Coues's gadwall (Anas strepera couesi), was the only distinct subspecies of the widespread gadwall.[13] It is surrounded by considerable mystery, mainly as regards the origin of the population, the age and therefore validity of the subspecies (it is sometimes disputed to be significantly distinct), and the causes and date of its disappearance. Only two specimens are known – a couple that is not fully mature, and therefore only limited information can be gleaned from it. What is certain is that there was a duck population of some size in the mid-1870s,[13] while in 1900 all were gone.

The bokikokiko (Acrocephalus aequinoctialis) is Kiribati's endemic reed-warbler. This small greyish passerine is well-known, due to its bold and inquisitive habits, and its song, a series of alternating higher and lower squeaks after which it is named.

The Rimitara lorikeet (Vini kuhlii) is present with about 1,000 birds. It is a tiny parrot with brilliant plumage and an endearing and highly social behavior, owing to which they were known to late 19th century settlers as "love-birds".[13] This species was originally native to the Austral and Cook Islands in SE Polynesia, a long distance to the south. They were treasured by the natives of the Society Islands and were an item of high value in inter-island trade; these birds were kept as pets, and in addition their feathers were used in crafts and art.[17] In any case, there is considerable evidence from Ancient Hawaiʻi that Polynesian seafarers travelled between southeastern Polynesia and Hawaiʻi with some regularity, perhaps as early as 400 AD, but certainly by about 1200 AD. Since it is almost inconceivable – given the prevailing winds, ocean currents, known trade routes, and the difficulty with which these birds can be kept alive during voyages[13] – that Vini kuhlii was transported from the Austral or Cook Islands to the Gilbert Islands and from there to Teraina, the presence of the birds there is best explained by them having been introduced by SE Polynesian travelers. Today, the species is extinct on many islands on which it formerly occurred, while the Teraina population, considered crucially important for its survival, contains some 60% of the remaining global wild population.[15] Ironically, the reason for the Rimitara lorikeet thriving on Teraina is the replacement of native forest with coconut plantations; these birds feed mainly on the nectar of coconut palm flowers and nest in old coconut shells or husks.[15]

As it thus seems clear that there was prehistoric human activity of some degree on Teraina, it is also likely that birds became extinct consequently, like on all such Outer Pacific islands for which research has been conducted. David Steadman in his comprehensive review lists several such hypothetical taxa for Kiribati as a whole. For Teraina specifically, considering the habitat and what birds still exist, one or more rails (Gallirallus and/or Porzana[18]), an imperial-pigeon (Ducula),[19] and maybe a Todiramphus kingfisher[20] or an Aplonis starling[21] make the most likely candidates for birds gone extinct prehistorically. It must be considered, however, that given the lack of fieldwork it is not quite clear what effect changing sea levels would have had on Teraina. If the sea level were only half a meter (c. 2 ft) higher it is certainly possible that the forest and freshwater lake would be replaced by shrubland or dunes and a brackish lagoon. That notwithstanding, it is well possible that a Polynesian sandpiper related to or identical with the Christmas sandpiper from Kiritimati once lived on Teraina.[22]

Other fauna

As with most outer Pacific islands, there are no native land mammals.

Polynesian rats (Rattus exulans) are present on Teraina,[15] apparently since prehistoric times. They may have arrived with flotsam after storms further west, or accidentally or deliberately (as food) been introduced by prehistoric seafarers. Their present-day impact on the bird population is minor, but if rails were once present on Teraina, the rats had probably some role in these birds' disappearance, and maybe in that of any other birds gone extinct in prehistoric times too. If a Polynesian sandpiper once bred on Teraina, it is almost certainly those rats that are responsible for these birds' disappearance; only a single taxon of Prosobonia remains today, precariously holding its own on atolls that are devoid of any rat species.

Feral dogs, cats and pigs occur in varying numbers on Teraina; the cats especially are responsible for some decline in the number of ground-nesting seabirds.[3] On the other hand, as noted above, the cats have thus far kept the rat population at bay.

Lacustrine species reported from Teraina include fish. and some unspecified "shrimp",[13] i.e. (in all probability) a member of the Crustacea. Teraina's freshwater fish include the marbled eel (Anguilla marmorata), a Caranx freshwater trevally, and Oreochromis tilapias and the milkfish (Chanos chanos). The latter two, and perhaps also the trevally, were introduced in recent times. The eels were already established by 1877;[13] like many Anguillidae they are catadromous and able to migrate some distance on dry land. Thus it may be presumed that the lake is continuously being restocked from the Pacific, though apparently no actual field data exists on the habits of the eels of Teraina.

As on many Indopacific islands rich in coconut (Cocos nucifera) trees, the coconut crab (Birgus latro) is often encountered on Teraina.[13]

A few green turtles (Chelonia mydas) nest on the beaches. It is not a very important nesting site however and the clutches have a rather low probability of success, as Teraina is one of the Kiribati islands where turtle egg collecting is permitted.[3]

See also

- Laysan Island – an eroded "dry" volcanic island, with a hypersaline lake

- Lisianski Island – an eroded "dry" volcanic island with completely infilled lagoon

- Rennell Island in Melanesia – in some respects like a much larger version of Teeraina

- List of Guano Island claims

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "22. Teeraina" (PDF). Office of Te Beretitenti – Republic of Kiribati Island Report Series. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ POK (2007)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Teeb'aki in Scott (1993)

- ↑ "20. Kiritimati" (PDF). Office of Te Beretitenti – Republic of Kiribati Island Report Series. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Resture (2004)

- ↑ Emory, K.P. (1934). "Archaeology of the Equatorial Pacific Islands". Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin. 123: 8–9 – via Babel.

- ↑ "Krusenstern".

- ↑ Bryan (1942)

- 1 2 "Islands for Sale – Romantic History of Fanning and Washington". V(12) Pacific Islands Monthly. 23 July 1935. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ Premier Postal History. "Post Office List". Premier Postal Auctions. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ "Teeraina" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2013.

- ↑ Streets (1877), Resture (2004)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Streets (1877)

- ↑ http://faculty.washington.edu/jsachs/lab/www/Research/Kiribati_Expedition_2005/Xmas130.jpg

- 1 2 3 4 5 BLI (2007)

- ↑ http://faculty.washington.edu/jsachs/lab/www/Research/Kiribati_Expedition_2005/Xmas134.jpg

- ↑ Tregear (1891)

- ↑ And perhaps one of the more aquatic Porphyrio swamphens as well. This is not explicitly mentioned by Steadman but plausible, given the unique lake habitat and the former presence of Porphyrio paepae on Hiva Oa.

- ↑ Such a bird would probably be related to the Pacific (D. pacifica)/Micronesian imperial-pigeon (D. oceanica) group occurring to the west of the Line Islands, or less likely to the Polynesian (D. aurorae)/Marquesan imperial-pigeons (D. galeata) occurring to the south.

- ↑ Such a bird would probably have belonged to the sacred kingfisher (T. sanctus) group; that species today occurs as a vagrant in Micronesia, and related forms are resident in SE Polynesia.

- ↑ This would probably have been related to the Micronesian starling (A. opaca) and the recently-extinct Pohnpei starling (A. pelzelni) or somewhat less probably to the extinct Huahine (A. diluvialis) and bay starlings (A. ulietensis) of the Society Islands.

- ↑ Steadman (2006)

References

- BirdLife International (BLI) (2007): Rimitara Lorikeet Species Factsheet. Retrieved 2008-FEB-24.

- Bryan, E.H. Jr. (1942): American Polynesia and the Hawaiian Chain (2nd ed.). Tongg Publishing Company, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Kiribati National Statistics Office (KNSO) (2006): 2005 Census of Population and Housing (provisional results).

- Parliament of Kiribati (POK) (2007): Constitution of Kiribati. Version of 2007-SEP-10. Retrieved 2007-OCT-10.

- Resture, Jane (2004): Washington Island – Line Islands. Version of 2004-FEB-08. Retrieved 2008-MAR-24.

- Scott, Derek A. (1993): Republic of Kiribati. In: A Directory of Wetlands in Oceania: 185-186.International Waterfowl and Wetlands Research Bureau, Slimbridge, UK and Asian Wetland Bureau, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Steadman, David William (2006): Extinction and Biogeography of Tropical Pacific Birds. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-77142-3

- Streets, Thomas H. (1877): Some Account of the Natural History of the Fanning Group of Islands. Am. Nat. 11(2): 65–72. First page image

- Tregear, Edward Robert (1891): Kaka. In: Maori-Polynesian Comparative Dictionary: 118. Lyon and Blair, Wellington. Online version 2005-FEB-16.

- Office of Te Beretitenti & T’Makei Services (2012): Teeraina. Ministry of Internal & Social Affairs, Republic of Kiribati. Archived 2017-05-29 at the Wayback Machine