| Sedum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Biting stonecrop (Sedum acre) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Saxifragales |

| Family: | Crassulaceae |

| Subfamily: | Sempervivoideae |

| Tribe: | Sedeae |

| Genus: | Sedum L.[1] |

| Type species | |

| Sedum acre | |

| Subgenera | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

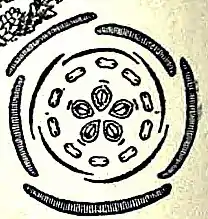

Sedum is a large genus of flowering plants in the family Crassulaceae, members of which are commonly known as stonecrops. The genus has been described as containing up to 600 species, subsequently reduced to 400–500. They are leaf succulents found primarily in the Northern Hemisphere, but extending into the southern hemisphere in Africa and South America. The plants vary from annual and creeping herbs to shrubs. The plants have water-storing leaves. The flowers usually have five petals, seldom four or six. There are typically twice as many stamens as petals. Various species formerly classified as Sedum are now in the segregate genera Hylotelephium and Rhodiola.

Well-known European species of Sedum are Sedum acre, Sedum album, Sedum dasyphyllum, Sedum reflexum (also known as Sedum rupestre) and Sedum hispanicum.

Description

Sedum is a genus that includes annual, biennial, and perennial herbs. They are characterised by succulent leaves and stems.[2] The extent of morphological diversity and homoplasy make it impossible to characterise Sedum phenotypicaly.[3]

Taxonomy

Sedum was first formally described by Carl Linnaeus in 1753, with 15 species.[4] Of the genera encompassed by the Crassulaceae family, Sedum is the most species rich, the most morphologically diverse and most complex taxonomically. Historically it was placed in the subfamily Sedoideae, of which it was the type genus. Of the three modern subfamilies of the Crassulaceae, based on molecular phylogenetics Sedum is placed in the subfamily Sempervivoideae. Although the genus has been greatly reduced, from about 600[5] to 420–470 species,[6] by forming up to 32 segregate genera,[7] it still constitutes a third of the family and is polyphyletic.[8]

Sedum species are found in four of six major crown clades wthin subfamily Sempervivoideae of Crassulaceae and are allocated to tribes, as follows:[9]

| Clade | Tribe |

|---|---|

| Hylotelephium | Telephieae |

| Rhodiola | Umbiliceae |

| Sempervivum | Semperviveae |

| Aeonium | Aeonieae |

| Acre | Sedeae |

| Leucosedum | |

| Note

Clades containing Sedum, shown in blue | |

In addition at least nine other distinct genera appear to be nested within Sedum. However the number of species found outside of the first two clades (Tribe Sedeae) are only a small fraction of the whole genus. Therefore the current circumscription, which is somewhat artificial and catch-all must be considered unstable.[8] The relationships between the tribes of Sempervivoideae is shown in the cladogram.

| Cladogram of Sempervivoideae tribes[9] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

There are now thought to be approximately 55 European species. Sedum demonstrates a wide variation in chromosome numbers, and polyploidy is common. Chromosome number is considered an important taxonomic feature.[10]

Earlier authors placed a number of Sedum species outside of these clades, such as S. spurium, S. stellatum and S. kamtschaticum (Telephium clade),[11] that has been segregated into Phedimus (tribe Umbiliceae).[9][12][13][14] Given the substantial taxonomic challenges presented by this highly polyphyletic genus, a number of radical solutions have been proposed for what is described as the "Sedum problem", all of which would require a substantial number of new combinations within Sempervivoideae. Nikulin and colleagues (2016) have recommended that, given the monophyly of Aeonieae and Semperviveae, species of Sedum outside of the tribe Sedeae (all in subgenus Gormania) be removed from the genus and reallocated. However this does not resolve the problem of other genera embedded within Sedum, in Sedeae.[8] In the largest published phylogenetic study (2020), the authors propose placing all taxa within Sedeae in genus Sedum, and transferring all other Sedum species in the remaining Sempervivoideae clades to other genera. This expanded Sedum s.l. would comprise about 755 species.[15]

Subdivision

Linnaeus originally described 15 species, characterised by pentamerous flowers, dividing them into two groups; Planifolia and Teretifolia, based on leaf morphology. with 15 species, and hence bears his name as the botanical authority (L.).[16] By 1828, de Candolle recognized 88 species, in six informal groups.[17] Various attempts have been made to subdivide this large genus, in addition to segregating separate genera, including creation of informal groups, sections, series and subgenera. For an extensive history of subfamily Sedoideae, see Ohba 1978.

Gray (1821) divided the 13 species known in Britain at that time into five sections; Rhodiola, Telephium, Sedum, (unnamed) and Aizoon.[18] In 1921 Praeger established ten sections; Rhodiola, Pseudorhodiola, Giraldiina, Telephium, Aizoon, Mexicana, Seda Genuina, Sempervivoides, Epeteium and Telmissa.[19] This was later revised in what is the best known system, that of Berger (1930), who defined 22 subdivisions, which he called Reihe (sections or series).[20] Berger's sections were:

- Rhodiola

- Pseudorhodiola

- Telephium

- Sedastrum

- Hasseanthus

- Lenophyllopsis

- Populisedum

- Graptopetalum

- Monanthella

- Perrierosedum

- Pachysedum

- Dendrosedum

- Fruticisedum

- Leptosedum

- Afrosedum

- Aizoon

- Seda genuina

- Prometheum

- Cyprosedum

- Epeteium

- Sedella

- Telmissa

A number of these, he further subdivided.[20] In contrast, Fröderströmm (1935) adopted a much broader circumscription of the genus, accepting only Sedum and Pseudosedum within the Sedoideae, dividing the former into 9 sections.[21] Although this was followed by numerous other systems, the most widely accepted infrageneric classification following Berger, was by Ohba (1978).[22] Prior to this most species in Sedoideae were placed in genus Sedum.[12] Of these systems, it was observed "No really satisfactory basis for the division of the family into genera has yet been proposed".[23]

Some other authors have added other series, and combined some of the series into groups, such as sections.[24] In particular Sedum section Sedum is divided into series (see Clades) [8][2] More recently, two subgenera have been recognised, Gormania and Sedum.[8]

- Gormania: (Britton) Clausen. 110 species from Sempervivum, Aeonium and Leucosedum clades. Europe and North America.

- Sedum: 320 species from Acre clade. Temperate and subtropical zones of Northern hemisphere (Asia and the Americas).[25]

Subgenus Sedum has been considered as three geographically distinct, but equal sized sections:[25]

- S. sect. Sedum ca. 120 spp. native to Europe, Asia Minor and N. Africa, ranging from N. Africa to central Scandinavia and from Iceland to the Ural Mountains, the Caucasus and Iran.

- S. sect. Americana Frod.

- S. sect. Asiatica Frod.

S. sect. Sedum includes 54 species native to Europe, which Berger classified into 27 series.[25]

Clades

Species and series include[26][27][28][11][9][8][7][29]

Subgenus Gormania

Of about 80 Eurasian species, series Rupestria forms a distinct monophyletic group of about ten taxa, which some authors have considered a separate genus, Petrosedum.[31][32][33] It was series 20 in Berger's classification. Native to Europe it has escaped cultivation and become naturalized in North America.[34] |

Embedded within series Monanthoidea are three Macaronesian segregate genera, Aichryson, Monanthes and Aeonium.[9] |

In the Levant, one species of this succulent (S. microcarpum) covers the stony ground like a carpet where the soil is shallow, growing no higher than 5–10 cm. At first, the fleshy leaves are a light green, but as the season progresses, the fleshy leaves turn red. |

Sedum microcarpum

Embedded within the Leucosedum clade are the following genera: Rosularia, Prometheum, Sedella and Dudleya.[9] Rosularia is paraphyletic, and some Sedum species, such as S. sempervivoides Fischer ex M. Bieberstein are assigned by some authors to Rosularia, as R. sempervivoides (Fischer ex M. Bieberstein) Boriss.[36] |

Subgenus Sedum

Embedded within the Acre clade are the following genera: Villadia, Lenophyllum, Graptopetalum, Thompsonella, Echeveria and Pachyphytum.[9] The species within Acre, can be broadly grouped into two subclades, American/European and Asian.[37][11] |

List of selected species

- Sedum acre L. – wall-pepper, goldmoss sedum, goldmoss stonecrop, biting stonecrop

- Sedum albomarginatum Clausen – Feather River stonecrop

- Sedum album L. – white stonecrop

- Sedum alfredii

- Sedum anglicum – English stonecrop

- Sedum brevifolium

- Sedum burrito – baby burro's-tail

- Sedum caeruleum

- Sedum cauticola

- Sedum clavatum

- Sedum cyprium

- Sedum dasyphyllum L. – thick-leaved stonecrop

- Sedum debile S.Watson – orpine stonecrop, weakstem stonecrop

- Sedum dendroideum Moc. & Sessé ex A.DC. – tree stonecrop

- Sedum divergens S.Watson – spreading stonecrop

- Sedum eastwoodiae (Britt.) Berger – Red Mountain stonecrop

- Sedum erythrostictum syn. Hylotelephium erythrostictum

- Sedum glaucophyllum Clausen – cliff stonecrop

- Sedum hispanicum L. – Spanish stonecrop

- Sedum lampusae (Kotschy) Boiss.

- Sedum lanceolatum Torr. – lance-leaf stonecrop, lanceleaf stonecrop, spearleaf stonecrop

- Sedum laxum (Britt.) Berger – roseflower stonecrop

- Sedum lineare – needle stonecrop

- Sedum mexicanum Britt. – Mexican stonecrop

- Sedum microstachyum (Kotschy) Boiss. – small-spiked stonecrop

- Sedum moranii Clausen – Rogue River stonecrop

- Sedum morganianum – donkey tail, burro tail

- Sedum multiceps – pygmy Joshua tree, dwarf Joshua tree

- Sedum niveum A.Davids. – Davidson's stonecrop

- Sedum nussbaumerianum Bitter, syn. Sedum adolphi – golden sedum

- Sedum oaxacanum Rose

- Sedum oblanceolatum Clausen – oblongleaf stonecrop

- Sedum obtusatum Gray – sierra stonecrop

- Sedum obtusatum ssp. paradisum Denton – paradise stonecrop

- Sedum ochroleucum Chaix – European stonecrop

- Sedum oreganum Nutt. – Oregon stonecrop

- Sedum oregonense (S.Watson) M.E.Peck – cream stonecrop

- Sedum palmeri S.Watson – Palmer's stonecrop

- Sedum perezdelarosae Jimeno-Sevilla

- Sedum porphyreum Kotschy – purple stonecrop

- Sedum pulchellum Michx. – widow's-cross

- Sedum radiatum S.Watson – Coast Range stonecrop

- Sedum rubrotinctum – pork and beans, Christmas cheer, jellybeans

- Sedum rupestre L. – reflexed stonecrop, blue stonecrop, Jenny's stonecrop, prick-madam

- Sedum sarmentosum Bunge – stringy stonecrop

- Sedum sediforme (Jacq.) Pau pale stonecrop

- Sedum sexangulare – tasteless stonecrop

- Sedum sieboldii – Siebold's stonecrop

- Sedum spathulifolium Hook.f. – Broadleaf stonecrop, Colorado stonecrop

- Sedum spurium – Caucasian stonecrop, dragon's blood sedum, two-row stonecrop

- Sedum stenopetalum Pursh – wormleaf stonecrop, yellow stonecrop

- Sedum telephium L.

- Sedum ternatum Michx. – woodland stonecrop

- Sedum takesimense

- Sedum telephium

- Sedum villosum – hairy stonecrop, purple stonecrop

- Sedum weinbergii

Distribution and habitat

Distributed in mainly in temperate to subtropical climates the Northern hemisphere, extending to the Southern hemisphere in Africa and South America,[6] being most diverse in the Mediterranean,[28] Central America, Himalayas, and East Asia.[2] In this respect, the two subgenera differ. Subgenus Sedum having a centre of diversity in Mexico, and Gormania in Eurasia with a secondary centre in N America. [28]

Ecology

Sedum species are used as food plants by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species including the grey chi moth. In particular, Sedum spathulifolium is the host plant of the endangered San Bruno elfin butterfly of San Mateo County, California. Sedum lanceolatum is the host plant of the more common Parnassius smintheus found in the Rocky Mountains.[38] As well as Sedum spathulifolium, many other species of Sedum serve the environmental role of host plants for butterflies. For example, the butterfly Callophrys xami uses several species of Sedum, such as Sedum allantoides, for suitable host plants.[39][40]

Uses

Ornamental

Many sedums are cultivated as ornamental garden plants, due to their interesting and attractive appearance and hardiness. The various species differ in their requirements; some are cold-hardy but do not tolerate heat, some require heat but do not tolerate cold.

Numerous hybrid cultivars have been developed, of which the following have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:[lower-alpha 2]

As food

The leaves of most stonecrops are edible,[45] excepting Sedum rubrotinctum, although toxicity has also been reported in some other species.[46] The juice from the stems and leaves may irritate skin if handled excessively.[47]

Sedum reflexum, known as "prickmadam", "stone orpine", or "crooked yellow stonecrop", is occasionally used as a salad leaf or herb in Europe, including the United Kingdom.[48] It has a slightly astringent sour taste.

Sedum divergens, known as "spreading stonecrop", was eaten by First Nations people in northwest British Columbia. The plant is used as a salad herb by the Haida and the Nisga'a people. It is common in the Nass Valley of British Columbia.[49]

Biting stonecrop (Sedum acre) contains high quantities of piperidine alkaloids (namely (+)-sedridine, (−)-sedamine, sedinone and isopelletierine), which give it a sharp, peppery, acrid taste and make it somewhat toxic.

Roofing

Sedum can be used to provide a roof covering in green roofs,[50][51] where they are preferred to grasses.[52] Examples include Ford's Dearborn, Michigan Truck Plant, which has a living roof with 454,000 square feet (42,200 m2) of sedum.[53] The Rolls-Royce Motor Cars plant in Goodwood, England, has a 242,000 square feet (22,500 m2) roof complex covered in Sedum, the largest in the United Kingdom.[54] Nintendo of America's roof is covered in some 75,000 square feet (7,000 m2) of Sedum.[55] The Javits Center in New York City is covered with 292,000 square feet (27,100 m2) of Sedum.[56]

Green tramway

Berlin's Prenzlauer Allee,[57] Le Mans, and Warsaw, for example, plant sedum in between rails of some tramways as a low maintenance alternative to grass. This provides beautification, a permeable surface for water management, and noise reduction.[58]

Gallery

Notes

- ↑ Unresolved name[30]

- ↑ Hylotelephium often considered a separate genus

References

- ↑ GRIN 2019.

- 1 2 3 Ito et al 2017.

- ↑ Nikulin & Gontcharov 2017.

- ↑ Linnaeus 1753.

- ↑ Ohba 1977.

- 1 2 Fu & Ohba 2001, p. 221.

- 1 2 Mort et al 2001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nikulin et al 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Thiede & Eggli 2007.

- ↑ Hart 1985.

- 1 2 3 van Ham & Hart 1998.

- 1 2 Ohba et al 2000.

- ↑ Fu & Ohba 2001, p. 220.

- ↑ ICN 2019.

- 1 2 Messerschmid et al 2020.

- ↑ Hart & Jarvis 1993.

- ↑ de Candolle 1828.

- ↑ Gray 1821.

- ↑ Praeger 1921.

- 1 2 Berger 1930.

- ↑ Fröderströmm 1935.

- ↑ Ohba 1978.

- ↑ Tutin et al 1993.

- ↑ Uhl 1978.

- 1 2 3 Hart & Alpinar 1991.

- ↑ Hart 1995.

- ↑ Hart 1995a.

- 1 2 3 Hart 1997.

- ↑ Ding et al 2019.

- ↑ TPL 2013.

- ↑ van Ham et al 1994.

- ↑ Gallo 2017.

- ↑ Gallo 2017a.

- ↑ Gallo & Zika 2014.

- ↑ Hart 2003, p. 41.

- ↑ WFO 2019.

- ↑ Mort et al 2009.

- ↑ Doyle 2011.

- ↑ Opler 1999.

- ↑ Ziegler & Escalante 1964.

- ↑ RHS 2019, Hylotelephium 'Herbstfreude'

- ↑ RHS 2019, Hylotelephium 'Bertram Anderson'

- ↑ RHS 2019, Hylotelephium 'Matrona'

- ↑ RHS 2019, Hylotelephium 'Ruby Glow'

- ↑ Pojar & MacKinnon 2004, p. 157.

- ↑ NCSU 2016.

- ↑ Reiner 1969, p. 56.

- ↑ PFAF 2012.

- ↑ Pojar & MacKinnon 2004, p. 156.

- ↑ NCSU 2019.

- ↑ Monterusso et al 2005.

- ↑ Kalinowski 2009.

- ↑ Greenroofs 2003.

- ↑ Sussex Life 2013.

- ↑ Totilo 2011.

- ↑ NYREJ 2013.

- ↑ "Green Tram Tracks" (PDF). Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ↑ Jakubcová, E.; Horváthová, E. (1 December 2020). "Costs and Benefits of Green Tramway Tracks". Scientia Agriculturae Bohemica. 51 (4): 99–106. doi:10.2478/sab-2020-0012. S2CID 231543550.

Bibliography

Books and theses

- Berger, A. (1930). "Crassulacaeae". In Engler, Adolf; Prantl, Karl Anton (eds.). Die Natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien. Vol. 18A. Leipzig: Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann. pp. 352–483.

- Doyle, Amanda (2011). The roles of temperature and host plant interactions in larval development and population ecology of Parnassius smintheus Doubleday, the Rocky Mountain Apollo butterfly (PDF) (M.Sc. thesis). University of Alberta, Department of Biological Sciences. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Eggli, Urs, ed. (2003). Illustrated Handbook of Succulent Plants: Crassulaceae. Springer Science & Business Media. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55874-0. ISBN 978-3-642-55874-0. S2CID 36280482.

- Fröderströmm, Harald (1935). The Genus Sedum L.: a systematic essay. Meddelanden från Göteborgs botaniska trädgärd vol. 7. Elander Boktryckeri Aktiebolag.

- Hart, H. 't; Eggli, U., eds. (1995). Evolution and systematics of the Crassulaceae. Leiden: Backhuys. ISBN 978-9073348462.

- Hart, H. 't (1995). Infrafamilial and generic classification of the Crassulaceae. pp. 159–172., in Hart & Eggli (1995)

- Hart, Henk 't (2003). Eggli, Urs (ed.). Sedums of Europe - Stonecrops and Wallpeppers. CRC Press. ISBN 978-90-5809-594-7.

- Opler, Paul A., ed. (1999) [1992]. "Xami hairstreak Callophrys xami". A Field Guide to Western Butterflies (2nd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 219. ISBN 0-395-79151-0.

- Pojar, Jim; MacKinnon, Andy (2004). Plants of Coastal British Columbia: Including Washington, Oregon and Alaska. Lone Pine Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55105-532-9.

- Reiner, Ralph E. (1969). Introducing the Flowering Beauty of Glacier National Park and the Majestic High Rockies. Glacier Park, Inc. ISBN 978-9110111493.

- Thiede, J; Eggli, U (2007). "Crassulaceae". In Kubitzki, Klaus (ed.). Berberidopsidales, Buxales, Crossosomatales, Fabales p.p., Geraniales, Gunnerales, Myrtales p.p., Proteales, Saxifragales, Vitales, Zygophyllales, Clusiaceae Alliance, Passifloraceae Alliance, Dilleniaceae, Huaceae, Picramniaceae, Sabiaceae. Springer. pp. 83–119. ISBN 978-3540322146. (full text at ResearchGate)

- Tutin, T. G.; Burges, N. A.; Edmondson, J. R., eds. (1993) [1964]. "Crassulaceae". Flora Europaea. Volume 1, Psilotaceae to Platanaceae (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-521-41007-6. see also Flora Europaea

- Historical

- de Candolle, A. P. (1828). "Sedum". Prodromus systematis naturalis regni vegetabilis, sive, Enumeratio contracta ordinum generum specierumque plantarum huc usque cognitarium, juxta methodi naturalis, normas digesta. Vol. 3. Paris: Treuttel et Würtz. pp. 401–410.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 580.

- Gray, Samuel Frederick (1821). "Sedum". A natural arrangement of British plants: according to their relations to each other as pointed out by Jussieu, De Candolle, Brown, &c. 2 vols. London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy. pp. ii: 539–543.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1753). "Sedum". Species Plantarum: exhibentes plantas rite cognitas, ad genera relatas, cum differentiis specificis, nominibus trivialibus, synonymis selectis, locis natalibus, secundum systema sexuale digestas. Vol. 1. Stockholm: Impensis Laurentii Salvii. pp. 430–432., see also Species Plantarum

Articles

- Ding, Hengwu; Zhu, Ran; Dong, Jinxiu; Bi, De; Jiang, Lan; Zeng, Juhua; Huang, Qingyu; Liu, Huan; Xu, Wenzhong; Wu, Longhua; Kan, Xianzhao (29 September 2019). "Next-Generation Genome Sequencing of Sedum plumbizincicola Sheds Light on the Structural Evolution of Plastid rRNA Operon and Phylogenetic Implications within Saxifragales". Plants. 8 (10): 386. doi:10.3390/plants8100386. PMC 6843225. PMID 31569538.

- Gallo, Lorenzo (24 August 2017a). "Towards a review of the genus Petrosedum (Crassulaceae): Taxonomic and nomenclatural notes on Iberian taxa". Webbia. 72 (2): 207–216. doi:10.1080/00837792.2017.1363978. S2CID 90686505.

- Gallo, Lorenzo (9 May 2017). "Nomenclatural novelties in Petrosedum (Crassulaceae)". Phytotaxa. 306 (2): 169. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.306.2.8.

- Gallo, Lorenzo; Zika, Peter (30 July 2014). "A taxonomic study of Sedum series Rupestria (Crassulaceae) naturalized in North America". Phytotaxa. 175 (1): 19. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.175.1.2.

- Grulich, Vit (1984). "Generic division of Sedoideae in Europe and the adjacent regions" (PDF). Preslia. 56: 29–45.

- van Ham, Roeland C. H. J.; Hart, Henk 't (March 1994). "Evolution of Sedum series Rupestria (Crassulaceae): Evidence from chloroplast DNA and biosystematic data". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 190 (1–2): 1–20. doi:10.1007/BF00937855. S2CID 25580936.

- Hart, H. 't (1995a). "The evolution of the Sedum acre group (Crassulaceae)" (PDF). Bocconea. 5: 119–128.

- Hart, H. 't (1985). "Chromosome Numbers in Sedum (Crassulaceae) from Greece". Willdenowia. 15 (1): 115–135. JSTOR 3996547.

- Hart, Henk 'T. (1997). "Diversity within Mediterranean Crassulaceae" (PDF). Lagascalia. 19 (1–2): 93–100.

- Hart, H. 'T; Alpinar, K. (1991). "Biosystematic Studies in Sedum (Crassulaceae) of Turkey. 1. Notes on Four Hitherto Little Known Species Collected in the Western Part of Anatolia". Willdenowia. 21 (1/2): 143–156. ISSN 0511-9618. JSTOR 3996600.

- Hart, H. 't; Jarvis, C. E. (May 1993). "Typification of Linnaeus's names for European species of Sedum subgen. Sedum". Taxon. 42 (2): 399–410. doi:10.2307/1223149. JSTOR 1223149.

- Ito, Takuro; Nakanishi, Hiroki; Chichibu, Yoshiro; Minoda, Kiyotaka; Kokubugata, Goro (9 June 2017). "Sedum danjoense (Crassulaceae), a new species of succulent plants from the Danjo Islands in Japan". Phytotaxa. 309 (1): 23. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.309.1.2.

- Mayuzumi, Shinzo; Ohba, Hideaki (2004). "The Phylogenetic Position of Eastern Asian Sedoideae (Crassulaceae) Inferred from Chloroplast and Nuclear DNA Sequences". Systematic Botany. 29 (3): 587–598. doi:10.1600/0363644041744329. ISSN 0363-6445. JSTOR 25063994. S2CID 84319808.

- Messerschmid, Thibaud F.E.; Klein, Johannes T.; Kadereit, Gudrun; Kadereit, Joachim W. (4 September 2020). "Linnaeus's folly – phylogeny, evolution and classification of Sedum (Crassulaceae) and Crassulaceae subfamily Sempervivoideae". Taxon. 69 (5): 892–926. doi:10.1002/tax.12316.

- Monterusso, Michael A; Rowe, D. Bradley; Rugh, Clayton L (2005). "Establishment and Persistence of Sedum spp. and Native Taxa for Green Roof Applications". HortScience. 40 (2): 391–396. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.40.2.391.

- Mort, Mark E.; Soltis, Douglas E.; Soltis, Pamela S.; Francisco-Ortega, Javier; Santos-Guerra, Arnoldo (January 2001). "Phylogenetic relationships and evolution of Crassulaceae inferred from matK sequence data". American Journal of Botany. 88 (1): 76–91. doi:10.2307/2657129. JSTOR 2657129. PMID 11159129.

- Mort, Mark E; O'Leary, T. Ryan; Carrillo-Reyes, Pablo; et al. (December 2009). "Phylogeny and evolution of Crassulaceae: Past, present, and future". Biodiversity & Ecology. 3: 69–86.

- Nikulin, Vyacheslav Yu.; Gontcharova, Svetlana B.; Stephenson, Ray; Gontcharov, Andrey A. (September 2016). "Phylogenetic relationships between Sedum L. and related genera (Crassulaceae) based on ITS rDNA sequence comparisons". Flora. 224: 218–229. doi:10.1016/j.flora.2016.08.003.

- Nikulin, Vyacheslav Yu; Gontcharov, Andrey A. (2017). "Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of Sedum L. (Crassulaceae) and closely related genera based on cpDNA gene matK and ITS rDNA sequence comparisons". Botanicheskii Zhurnal (in Russian). 102 (2): 309–328.

- Ohba, Hideaki (March 1977). "The taxonomic status of Sedum telephium and its allied species (Crassulaceae)". The Botanical Magazine Tokyo. 90 (1): 41–56. doi:10.1007/BF02489468. S2CID 22239507.

- Ohba, H (1978). "Generic and infrageneric classification of the old world sedoideae crassulaceae". Journal of the Faculty of Science University of Tokyo Section III Botany 12(4): 139-193. 12 (4): 139–193.

- Ohba, Hideaki; Bartholomew, Bruce M; Turland, Nicholas J; Kunjun, Fu (2000). "New Combinations in Phedimus (Crassulaceae)". Novon. 10 (4): 400–402. doi:10.2307/3392995. JSTOR 3392995.

- Praeger, R. Lloyd (1921). "An account of the genus Sedum as found in cultivation". Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society. 46: 1–314.

- Uhl, Charles H. (1978). "Chromosomes of Mexican Sedum II. Section Pachysedum". Rhodora. 80 (824): 491–512. ISSN 0035-4902. JSTOR 23311260.

- van Ham, Roeland C. H. J.; Hart, Henk ’t (January 1998). "Phylogenetic relationships in the Crassulaceae inferred from chloroplast DNA restriction-site variation". American Journal of Botany. 85 (1): 123–134. doi:10.2307/2446561. JSTOR 2446561. PMID 21684886.

- Ziegler, J. Benjamin; Escalante, Tarsicio (1964). "Observations on the Life History of Callophrys Xami (Lycaenidae)" (PDF). Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society. 18 (2): 85–89.

- Zika, Peter F.; Wilson, Barbara L.; Brainerd, Richard E.; Otting, Nick; Darington, Steven; Knaus, Brian J.; Nelson, Julie Kierstead (10 September 2018). "A review of Sedum section Gormania (Crassulaceae) in western North America". Phytotaxa. 368 (1): 1. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.368.1.1.

Websites

- Cammidge, Jacki (2019). "Succulents and Water Wise Perennials". Drought Smart Plants. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- "Sedum Society". www.cactus-mall.com. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Faucon, Philippe (2004). "Plants Belonging to the Genus 'Sedum'". Desert Tropicals. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "Find a plant". Royal Horticultural Society. 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "Sedum spp". North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- "Sedum". Plant toolbox. North Carolina State University. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- PFAF (2012). "Sedum rupestre L. Crooked Yellow Stonecrop PFAF Plant Database". PFAF Plant Database. Plants for a Future.

- "Rolls-Royce - Made in Sussex". Sussex Life. 20 February 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- Totilo, Stephen (25 August 2011). "The Coolest Things in Nintendo's American Headquarters (And One Uncool Thing)". Kotaku. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- "Project of the Month: FXFOWLE, Epstein and Tishman complete renovation/ expansion of $465 million Jacob K. Javits Convention Center". New York Real Estate Journal. 9 December 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- Kalinowski, Tess (4 August 2009). "Green roof takes root at Eglinton West". Toronto Star. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- "Ford Motor Company's River Rouge Truck Plant". Projects. Greenroofs. 2003.

- "International Crassulaceae Network". Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Databases and flora

- Fu, Kunjun; Ohba, Hideaki; Gilbert, Michael. "Crassulaceae Candolle". Flora of China. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

Fu, Kunjun; Ohba, Hideaki (2001). "CRASSULACEAE Candolle" (PDF). Flora of China. Vol. 8. pp. 202–268.- "Sedum Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 430. 1753". Flora of China. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

"SEDUM Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 430. 1753" (PDF). Flora of China. Vol. 8. 2001. pp. 221–251. - "PHEDIMUS Rafinesque, Amer. Monthly Mag. & Crit. Rev. 1: 438. 1817" (PDF). Flora of China. Vol. 8. 2001. pp. 218–220.

- "Sedum Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 430. 1753". Flora of China. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- GRIN (2019). "Sedum L." National Plant Germplasm System. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- Stevens, P.F. (2019) [2001]. "Crassulaceae". Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 4 August 2019. (see also Angiosperm Phylogeny Website)

- TPL (2013). "The Plant List Version 1.1: Sedum". Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- WFO (2019). "Sedum L." World Flora Online. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "Sedum L." Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

.jpg.webp)