Mark the Evangelist | |

|---|---|

Detail from a window in the parish church of SS Mary and Lambert, Stonham Aspal, Suffolk, with stained glass representing St Mark the Evangelist | |

| Evangelist, Martyr | |

| Born | c. 12 AD Cyrene, Pentapolis of North Africa (according to Coptic tradition)[1] |

| Died | c. 68 AD (aged c. 56) Alexandria, Egypt, Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | All Christian churches that venerate saints |

| Major shrine | |

| Feast |

|

| Patronage | Barristers, Venice,[2] Egypt, Copts,[3] Mainar, Podgorica[4] |

| Major works | Gospel of Mark (attributed) |

Mark the Evangelist[lower-alpha 1] also known as John Mark or Saint Mark, is the person who is traditionally ascribed to be the author of the Gospel of Mark. Modern Bible scholars have concluded that the Gospel of Mark was written by an anonymous author rather than by Mark.[5][6][7][8] According to Church tradition, Mark founded the episcopal see of Alexandria, which was one of the five most important sees of early Christianity. His feast day is celebrated on April 25, and his symbol is the winged lion.[9]

Identity

According to William Lane (1974), an "unbroken tradition" identifies Mark the Evangelist with John Mark,[10] and John Mark as the cousin of Barnabas.[11] However, Hippolytus of Rome, in On the Seventy Apostles, distinguishes Mark the Evangelist (2 Timothy 4:11),[12] John Mark (Acts 12:12, 25; 13:5, 13; 15:37),[13] and Mark the cousin of Barnabas (Colossians 4:10;[14] Philemon 1:24).[15][16] According to Hippolytus, they all belonged to the "Seventy Disciples" who were sent out by Jesus to disseminate the gospel (Luke 10:1ff.)[17] in Judea.

According to Eusebius of Caesarea,[18] Herod Agrippa I, in his first year of reign over the whole of Judea (AD 41), killed James, son of Zebedee and arrested Peter, planning to kill him after the Passover. Peter was saved miraculously by angels, and escaped out of the realm of Herod (Acts 12:1–19).[19] Peter went to Antioch, then through Asia Minor (visiting the churches in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia, as mentioned in 1 Peter 1:1),[20] and arrived in Rome in the second year of Emperor Claudius (AD 42).[21] Somewhere on the way, Peter encountered Mark and took him as travel companion and interpreter. Mark the Evangelist wrote down the sermons of Peter, thus composing the Gospel according to Mark,[22] before he left for Alexandria in the third year of Claudius (AD 43).[23]

According to the Acts 15:39,[24] Mark went to Cyprus with Barnabas after the Council of Jerusalem.

According to tradition, in AD 49, about 19 years after the Ascension of Jesus, Mark travelled to Alexandria and founded the Church of Alexandria. The Coptic Orthodox Church, the Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria, and the Coptic Catholic Church all trace their origins to this original community.[25] Aspects of the Coptic liturgy can be traced back to Mark himself.[26] He became the first bishop of Alexandria and he is honored as the founder of Christianity in Africa.[27]

According to Eusebius,[28] Mark was succeeded by Anianus as the bishop of Alexandria in the eighth year of Nero (62/63), probably, but not definitely, due to his coming death. Later Coptic tradition says that he was martyred in 68.[1][29][30][31][15]

Modern Bible scholars (i.e. most critical scholars) have concluded that the Gospel of Mark was written by an anonymous author rather than by Mark.[32][33][34][35][5][6][7][8][36][37][38][39][40][41] For instance, the author of the Gospel of Mark knew very little about the geography of Palestine (having apparently never visited it),[42][43][44][45][46] "was very far from being a peasant or a fisherman",[42] was unacquainted with Jewish customs (unlikely for someone from Palestine),[45][46] and was probably "a Hellenized Jew who lived outside of Palestine".[47] Mitchell Reddish does concede that the name of the author might have been Mark (making the gospel possibly homonymous), but the identity of this Mark is unknown.[46] Similarly, "Francis Moloney suggests the author was someone named Mark, though maybe not any of the Marks mentioned in the New Testament".[48] The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus takes the same approach: the author was named Mark, but scholars are undecided who this Mark was.[45]

The four canonical gospels are anonymous and most researchers agree that none of them was written by eyewitnesses.[49][50][51][52] Some conservative researchers defend their traditional authorship, but for a variety of reasons most scholars have abandoned this theory or support it only tenuously.[53]

Biblical and traditional information

Evidence for Mark the Evangelist's authorship of the Gospel of Mark that bears his name originates with Papias (c. 60 – c. 130 AD).[54][55][56] Scholars of the Trinity Evangelical Divinity School are "almost certain" that Papias is referencing John Mark.[57] Modern mainstream Bible scholars find Papias's information difficult to interpret.[58]

The Coptic Church accords with identifying Mark the Evangelist with John Mark, as well as that he was one of the Seventy Disciples sent out by Jesus (Luke 10:1),[17] as Hippolytus confirmed.[59] Coptic tradition also holds that Mark the Evangelist hosted the disciples in his house after Jesus's death, that the resurrected Jesus came to Mark's house (John 20), and that the Holy Spirit descended on the disciples at Pentecost in the same house.[59] Furthermore, Mark is also believed to have been among the servants at the Marriage at Cana who poured out the water that Jesus turned to wine (John 2:1–11).[60][59]

According to the Coptic tradition, Mark was born in Cyrene, a city in the Pentapolis of North Africa (now Libya). This tradition adds that Mark returned to Pentapolis later in life, after being sent by Paul to Colossae (Colossians 4:10;[14] Philemon 24.)[61] Some, however, think these actually refer to Mark the Cousin of Barnabas), and serving with him in Rome (2 Timothy 4:11);[12] from Pentapolis he made his way to Alexandria.[62][63] When Mark returned to Alexandria, the pagans of the city resented his efforts to turn the Alexandrians away from the worship of their traditional gods.[64] In AD 68, they placed a rope around his neck and dragged him through the streets until he was dead.[64]

Veneration

The Feast of St Mark is observed on April 25 by the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. For those Churches still using the Julian calendar, April 25 according to it aligns with May 8 on the Gregorian calendar until the year 2099. The Coptic Orthodox Church observes the Feast of St Mark on Parmouti 30 according to the Coptic calendar which always aligns with April 25 on the Julian calendar or May 8 on the Gregorian calendar.

Where John Mark is distinguished from Mark the Evangelist, John Mark is celebrated on September 27 (as in the Roman Martyrology) and Mark the Evangelist on April 25.

Mark is remembered in the Church of England and in much of the Anglican Communion, with a Festival on 25 April.[65]

In art

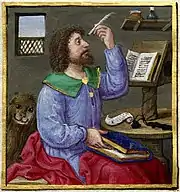

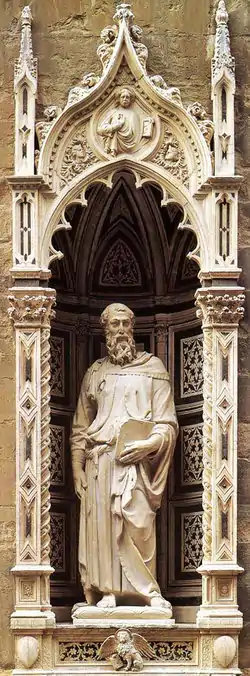

Mark the Evangelist is most often depicted writing or holding his gospel.[66] In Christian tradition, Mark the Evangelist is symbolized by a winged lion.[67]

Mark the Evangelist attributes are the lion in the desert; he can be depicted as a bishop on a throne decorated with lions; as a man helping Venetian sailors. He is often depicted holding a book with pax tibi Marce written on it or holding a palm and book. Other depictions of Mark show him as a man with a book or scroll, accompanied by a winged lion. The lion might also be associated with Jesus' Resurrection because lions were believed to sleep with open eyes, thus a comparison with Christ in his tomb, and Christ as king.

Mark the Evangelist can be depicted as a man with a halter around his neck and as rescuing Christian slaves from Saracens.

- Depictions of Mark the Evangelist

Venetian merchants with the help of two Greek monks take Mark the Evangelist's body to Venice, by Tintoretto

Venetian merchants with the help of two Greek monks take Mark the Evangelist's body to Venice, by Tintoretto Mark the Evangelist listening to the winged lion, Mark; image 21 of the Codex Aureus of Lorsch or Lorsch Gospels

Mark the Evangelist listening to the winged lion, Mark; image 21 of the Codex Aureus of Lorsch or Lorsch Gospels%252C_epernay%252C_Biblioth%C3%A8que_municipale%252C_Ms._1_f_18_v.%252C_20%252C8x26_cm%252C_ante_823.jpg.webp) Mark the Evangelist looking at the lion, c. 823

Mark the Evangelist looking at the lion, c. 823 The martyrdom of Saint Mark. Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry (Musée Condé, Chantilly), c. 1412 and 1416.

The martyrdom of Saint Mark. Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry (Musée Condé, Chantilly), c. 1412 and 1416. St Mark by Andrea Mantegna, 1448

St Mark by Andrea Mantegna, 1448 Mark the Evangelist with the lion, 1524

Mark the Evangelist with the lion, 1524 A painted miniature in an Armenian Gospel manuscript from 1609, held by the Bodleian Library

A painted miniature in an Armenian Gospel manuscript from 1609, held by the Bodleian Library Saint Mark on a 17th-century naive painting by unknown artist in the choir of St Mary church (Sankta Maria kyrka) in Åhus, Sweden

Saint Mark on a 17th-century naive painting by unknown artist in the choir of St Mary church (Sankta Maria kyrka) in Åhus, Sweden St. Mark writes his Evangelium at the dictation of St. Peter, by Pasquale Ottino, 17th century, Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux

St. Mark writes his Evangelium at the dictation of St. Peter, by Pasquale Ottino, 17th century, Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux Mark the Evangelist by Il Pordenone (c. 1484–1539)

Mark the Evangelist by Il Pordenone (c. 1484–1539) Saint Mark the Evangelist Icon from the royal gates of the central iconostasis of the Kazan Cathedral in Saint Petersburg, 1804

Saint Mark the Evangelist Icon from the royal gates of the central iconostasis of the Kazan Cathedral in Saint Petersburg, 1804 An icon of Saint Mark the Evangelist, 1657

An icon of Saint Mark the Evangelist, 1657

St Mark in the Nuremberg Chronicle

St Mark in the Nuremberg Chronicle

Major shrines

See also

Notes

- ↑ Latin: Marcus; Ancient Greek: Μᾶρκος, romanized: Mârkos; Imperial Aramaic: ܡܪܩܘܣ, romanized: Marqōs; Hebrew: מַרְקוֹס, romanized: Marqōs; Ge'ez: ማርቆስ, romanized: Marḳos.

References

Citations

- 1 2 "St. Mark The Apostle, Evangelist". Coptic Orthodox Church Network. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- ↑ Walsh, p. 21.

- ↑ Lewis, Agnes Smith (2008). Through Cyprus. University of Michigan Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-88402-284-8.

St. Mark is the patron saint of the Copts.

- ↑ "Markovdan: Slava Podgorice". Borba. May 8, 2023.

- 1 2 E. P. Sanders (30 November 1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin Books Limited. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-14-192822-7.

We do not know who wrote the gospels. They presently have headings: 'according to Matthew', 'according to Mark', 'according to Luke' and 'according to John'. The Matthew and John who are meant were two of the original disciples of Jesus. Mark was a follower of Paul, and possibly also of Peter; Luke was one of Paul's converts.5 These men – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John – really lived, but we do not know that they wrote gospels. Present evidence indicates that the gospels remained untitled until the second half of the second century.

- 1 2 Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1.

Why then do we call them Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John? Because sometime in the second century, when proto-orthodox Christians recognized the need for apostolic authorities, they attributed these books to apostles (Matthew and John) and close companions of apostles (Mark, the secretary of Peter; and Luke, the traveling companion of Paul). Most scholars today have abandoned these identifications,11 and recognize that the books were written by otherwise unknown but relatively well-educated Greek-speaking (and writing) Christians during the second half of the first century.

- 1 2 Nickle, Keith Fullerton (January 1, 2001). The Synoptic Gospels: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-664-22349-6.

We must candidly acknowledge that all three of the Synoptic Gospels are anonymous documents. None of the three gains any importance by association with those traditional figures out of the life of the early church. Neither do they lose anything in importance by being recognized to be anonymous. Throughout this book the traditional names are used to refer to the authors of the first three Gospels, but we shall do so simply as a device of convenience.

- 1 2 Ehrman, Bart D. (November 1, 2004). Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-0-19-534616-9.

We call these books, of course, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. And for centuries Christians have believed they were actually written by these people: two of the disciples of Jesus, Matthew the tax collector (see Matt. 9:9) and John, the "beloved disciple" (John 21:24), and two companions of the apostles, Mark, the secretary of Peter, and Luke, the traveling companion of Paul. These are, after all, the names found in the titles of these books. But what most people don't realize is that these titles were added later, by second-century Christians, decades after the books themselves had been written, in order to be able to claim that they were apostolic in origin. Why would later Christians do this? Recall our earlier discussion of the formation of the New Testament canon: only those books that were apostolic could be included. What was one to do with Gospels that were widely read and accepted as authoritative but that in fact were written anonymously, as all four of the New Testament Gospels were? They had to be associated with apostles in order to be included in the canon, and so apostolic names were attached to them.

- ↑ Senior, Donald P. (1998), "Mark", in Ferguson, Everett (ed.), Encyclopedia of Early Christianity (2nd ed.), New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., p. 720, ISBN 0-8153-3319-6

- ↑ Lane, William L. (1974). "The Author of the Gospel". The Gospel According to Mark. New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. pp. 21–3. ISBN 978-0-8028-2502-5.

- ↑ Mark: Images of an Apostolic Interpreter p55 C. Clifton Black – 2001 –"... infrequent occurrence in the Septuagint (Num 36:11; Tob 7:2) to its presence in Josephus (JW 1.662; Ant 1.290, 15.250) and Philo (On the Embassy to Gaius 67), anepsios consistently carries the connotation of "cousin", though ..."

- 1 2 2 Timothy 4:11

- ↑ Acts 12:12–25, Acts 13:5–13, Acts 15:37

- 1 2 Colossians 4:10

- 1 2 Philemon 1:24

- ↑ Hippolytus. "The same Hippolytus on the Seventy Apostles". Ante-Nicene Fathers.

- 1 2 Luke 10:1

- ↑ The Ecclesiastical History 2.9.1–4

- ↑ Acts 12:1–19

- ↑ 1 Peter 1:1

- ↑ The Ecclesiastical History 2.14.6

- ↑ The Ecclesiastical History 15–16

- ↑ Finegan, Jack (1998). Handbook of Biblical Chronology. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson. p. 374. ISBN 978-1-56563-143-4.

- ↑ Acts 15:39

- ↑ "Egypt". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Archived from the original on December 20, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2011. See drop-down essay on "Islamic Conquest and the Ottoman Empire"

- ↑ "The Christian Coptic Orthodox Church Of Egypt". Encyclopedia Coptica. Archived from the original on August 31, 2005. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ↑ Bunson, Matthew; Bunson, Margaret; Bunson, Stephen (1998). Our Sunday Visitor's Encyclopedia of Saints. Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor Publishing Division. p. 401. ISBN 0-87973-588-0.

- ↑ The Ecclesiastical History 2.24.1

- ↑ "Catholic Encyclopedia, St. Mark". Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ↑ Acts 15:36–40

- ↑ 2 Timothy 4:11

- ↑ Ehrman, Bart D. (2004). The New Testament. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 58–59. ISBN 0-19-515462-2.

Proto-orthodox Christians of the second century, some decades after most of the New Testament books had been written, claimed that their favorite Gospels had been penned by two of Jesus' disciples—Matthew, the tax collector, and John, the beloved disciple—and by two friends of the apostles—Mark, the secretary of Peter, and Luke, the travelling companion of Paul. Scholars today, however, find it difficult to accept this tradition for several reasons.

- ↑ Easley, Kendell H. (2002). Holman Quicksource Guide to Understanding the Bible: A Book-By-Book Overview. B&H Publishing Group. p. PT233. ISBN 978-1-4336-7134-0. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

Most critical scholars deny that Mark was the author or that he wrote on the basis of Peter's recollections

- ↑ Craig, William Lane; Lüdemann, Gerd; Copan, Paul; Tacelli, Ronald K. (2000). Jesus' Resurrection: Fact Or Figment?: A Debate Between William Lane Craig & Gerd Ludemann (in Dutch). InterVarsity Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8308-1569-2. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

I wanted to use that quotation in order to show that the results of historical scholarship can be made known to the public—especially to believers—only with difficulty. Many Christians feel threatened if they hear that most of what was written in the Bible is (in historical terms) untrue and that none of the four New Testament Gospels was written by the author listed at the top of the text.

- ↑ Jeon, Jeong Koo; Baugh, Steve (2017). Biblical Theology: Covenants and the Kingdom of God in Redemptive History. Wipf & Stock. p. 181 fn. 10. ISBN 978-1-5326-0580-2. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

10. Just as historical critical scholars deny the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch, so they also deny the authorship of the four Gospels by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. [...] But today, these persons are not thought to have been the actual authors.

- ↑ Bart D. Ehrman (2000:43) The New Testament: a historical introduction to early Christian writings. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Ehrman, Bart D. (2006). The Lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot: A New Look at Betrayer and Betrayed. Oxford University Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-19-971104-8. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

The Gospels of the New Testament are therefore our earliest accounts. These do not claim to be written by eyewitnesses to the life of Jesus, and historians have long recognized that they were produced by second- or third-generation Christians living in different countries than Jesus (and Judas) did, speaking a different language (Greek instead of Aramaic), experiencing different situations, and addressing different audiences.

- ↑ Ehrman, Bart D. (2000). The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings. Oxford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-19-512639-6. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

We have already learned significant bits of information about these books. They were written thirty-five to sixty-five years after Jesus' death by authors who did not know him, authors living in different countries who were writing at different times to different communities with different problems and concerns. The authors all wrote in Greek and they all used sources for the stories they narrate. Luke explicitly indicates that his sources were both written and oral. These sources appear to have recounted the words and deeds of Jesus that had been circulating among Christian congregations throughout the Mediterranean world. At a later stage we will consider the question of the historical reliability of these stories. Here we are interested in the Gospels as pieces of early Christian literature.

- ↑ Boring, M. Eugene (2012). An Introduction to the New Testament: History, Literature, Theology. Presbyterian Publishing Corporation. p. 522. ISBN 978-0-664-25592-3. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

Beginning with Papias in the second century, a tradition developed in various forms that attributed the authorship of the Gospel of Mark to this John Mark, who had been the companion of both Paul and Peter (Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 3.39.15). In all its variations, the ancient tradition makes clear that Mark's Gospel was accepted and valued in the church, not because of its historical accuracy, but because it represented Peter's apostolic authority. The Gospel of Mark itself makes no claim to have been written by an eyewitness and gives no evidence of such authorship. While most critical scholars consider the actual author's name to be unknown, the traditional view that Mark was written in Rome by a companion of Peter is still defended by some scholars who begin with the church tradition cited above and do not find convincing historical evidence to disprove it.6 For convenience, in this book we continue to refer to the Gospels by the names of their traditional authors.

- ↑ Ray, Ronald R. (2018). Systematics Critical and Constructive 1: Biblical-Interpretive-Theological-Interdisciplinary. Pickwick Publications. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-5326-0016-6. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

Authorship by an apostle was so unimportant to early recognition of a writing's authority that names of apostles (Matthew and John) or names of people thought to be associated with apostles (Mark and Luke respectively with Peter and Paul) were only attached to the four Gospels at the beginning of the second century, after those had gained recognition primarily because of churchly appreciation of their content. Having studied the content of John and Matthew, historical-critical scholarship massively doubts that the Hellenistic Fourth Gospel was authored by the apostle John, and widely doubts that the First Gospel was written by the apostle Matthew. That the author of Mark was Peter's associate also seems unlikely, since that Gospel is very Hellenistic and Peter—according to both Acts and Paul—was highly Jewish. Similarly, that the author of Luke was Paul's companion is most improbable, since Acts's accounts concerning Paul conflict much with what Paul's epistles report. Again, had any of the Gospels been written by apostles, why were their names attached so late?125 Nor would apostle associates have been apostles!

- ↑ Which is not a new claim, see Foster, Douglas A. (2012). The Encyclopedia of the Stone-Campbell Movement. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4674-2736-4. Retrieved 15 August 2023.

During this period Disciples scholars such as Willett began to study at interdenominational theological schools and secular universities, and for the first time the Stone-Campbell Movement engaged historical criticism as the primary perspective on biblical interpretation. While Campbell's "Seven Rules" had advocated a kind of historical criticism, traditional conclusions about authorship, date, and the nature of biblical documents had been assumed, so that no one in the first generation had supposed that the consistent application of Campbell's own principles would lead to results that challenged and overturned these conclusions. By the end of the nineteenth century, those who followed the critical method arrived at a new set of conclusions that made the Bible look entirely different. Among these new conclusions: the Pentateuch was not written by Moses but represented a long development within history, the prophets were not making long-range predictions about Jesus and the church, but spoke to the issues of their own time; the Gospels were not independent 'testimonies" that provided "evidence" for the historical facts about Jesus' life and teaching, but were interdependent (Matthew and Luke used Mark and "Q"); also, the Gospels were not written by apostles and contained several layers of reinterpreted traditions.

- 1 2 Leach, Edmund (1990). "Fishing for men on the edge of the wilderness". In Alter, Robert; Kermode, Frank (eds.). The Literary Guide to the Bible. Harvard University Press. p. 590. ISBN 978-0-674-26141-9.

5. The geography of Gospel Palestine, like the geography of Old Testament Palestine, is symbolic rather than actual. It is not clear whether any of the evangelists had ever been there.

- ↑ Wells, George Albert (2013). Cutting Jesus Down to Size: What Higher Criticism Has Achieved and Where It Leaves Christianity. Open Court. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-8126-9867-1. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

Mark's knowledge even of Palestine's geography is likewise defective. [...] Kümmel (1975, p. 97) writes of Mark's "numerous geographical errors"

- ↑ Hengel, Martin (2003). Between Jesus and Paul: Studies in the Earliest History of Christianity. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-7252-0077-7. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

Furthermore, it is more than doubtful whether evangelists like Mark or Luke ever caught sight of a map of Palestine.

- 1 2 3 Hatina, Thomas R. (2014). "Gospel of Mark". In Evans, Craig A. (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Taylor & Francis. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-317-72224-3. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

Like the other synoptics, Mark's Gospel is anonymous. Whether it was originally so is, however, difficult to know. Nevertheless, we can be fairly certain that it was written by someone named Mark. [...] The difficulty is ascertaining the identity of Mark. Scholars debate [...] or another person simply named Mark who was not native to Palestine. Many scholars have opted for the latter option due to the Gospel's lack of understanding of Jewish laws (1:40–45; 2:23–28; 7:1–23), incorrect Palestinian geography (5:1–2, 12–13; 7:31), and concern for Gentiles (7:24–28:10) (e.g. Marcus 1999: 17–21)

- 1 2 3 Reddish 2011, p. 36: "Evidence in the Gospel itself has led many readers of the Gospel to question the traditional view of authorship. The author of the Gospel does not seem to be too familiar with Palestinian geography. [...] Is it likely that a native of Palestine, as John Mark was, would have made such errors?" [...] Also, certain passages in the Gospel contain erroneous statements about Palestinian or Jewish practices."

- ↑ Watts Henderson, Suzanne (2018). "The Gospel according to Mark". In Coogan, Michael; Brettler, Marc; Newsom, Carol; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. p. 1431. ISBN 978-0-19-027605-8. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

suggest that the evangelist was a Hellenized Jew who lived outside of Palestine.

- ↑ Tucker, J. Brian; Kuecker, Aaron (2020). T&T Clark Social Identity Commentary on the New Testament. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-567-66785-4. Retrieved 13 August 2023.

Francis Moloney suggests the author was someone named Mark, though maybe not any of the Marks mentioned in the New Testament (Moloney, 11-12).

- ↑ Millard, Alan (2006). "Authors, Books, and Readers in the Ancient World". In Rogerson, J.W.; Lieu, Judith M. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 558. ISBN 978-0-19-925425-5.

The historical narratives, the Gospels and Acts, are anonymous, the attributions to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John being first reported in the mid-second century by Irenaeus

- ↑ Reddish 2011, pp. 13, 42.

- ↑ Cousland 2010, p. 1744.

- ↑ Cousland 2018, p. 1380.

- ↑ Lindars, Edwards & Court 2000, p. 41.

- ↑ "From Stories to Canon" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-05. Retrieved 2023-08-20.

- ↑ Papias (1885). . Ante-Nicene Christian Library, Volume I. Translated by Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. T. & T. Clark in Edinburgh.

- ↑ Harrington, Daniel J. (1990), "The Gospel According to Mark", in Brown, Raymond E.; Fitzmyer, Joseph A.; Murphy, Roland E. (eds.), The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, p. 596, ISBN 0-13-614934-0

- ↑ D. A. Carson, Douglas J. Moo and Leon Morris, An Introduction to the New Testament (Apollos, 1992), 93.

- ↑ Wansbrough, Henry (22 April 2010). Muddiman, John; Barton, John (eds.). The Gospels. Oxford University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-19-958025-5.

Finally it is important to realize that none of the four gospels originally included an attribution to an author. All were anonymous, and it is only from the fragmentary and enigmatic and—according to Eusebius, from whom we derive the quotation—unreliable evidence of Papias in 120/130 CE that we can begin to piece together any external evidence about the names of their authors and their compilers. This evidence is so difficult to interpret that most modern scholars form their opinions from the content of the gospels themselves, and only then appeal selectively to the external evidence for confirmation of their findings.

- 1 2 3 Pope Shenouda III, The Beholder of God Mark the Evangelist Saint and Martyr, Chapter One. Tasbeha.org

- ↑ John 2:1–11

- ↑ Philemon 24

- ↑ "About the Diocese". Coptic Orthodox Diocese of the Southern United States.

- ↑ "Saint Mark". Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- 1 2 Pope Shenouda III. The Beholder of God Mark the Evangelist Saint and Martyr, Chapter Seven. Tasbeha.org

- ↑ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

- ↑ Didron, Adolphe Napoléon (February 20, 1886). Christian Iconography: The Trinity. Angels. Devils. Death. The soul. The Christian scheme. Appendices. G. Bell. p. 356 – via Internet Archive.

St. Mark iconography.

- ↑ "St. Mark in Art". www.christianiconography.info.

Bibliography

- Fant, Clyde E.; Reddish, Mitchell E. (2008). Lost Treasures of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2881-1.

- Reddish, Mitchell (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1-4267-5008-3.

- Cousland, J.R.C. (2010). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. p. 1744. ISBN 978-0-19-528955-8.

- Cousland, J.R.C. (1 March 2018). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. p. 1380. ISBN 978-0-19-027605-8.

- Lindars, Barnabas; Edwards, Ruth; Court, John M. (2000). The Johannine Literature. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84127-081-4.