Thomas Southwood Smith | |

|---|---|

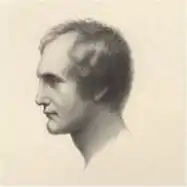

Southwood Smith, 1844 engraving by James Charles Armytage after a drawing by Margaret Gillies. | |

| Born | 21 December 1788. |

| Died | 10 December 1861 (aged 72) |

| Occupation(s) | Physician and sanitary reformer |

Thomas Southwood Smith (1788 – 1861) was an English physician and sanitary reformer.

Early life

Smith was born at Martock, Somerset, into a strict Baptist family, his parents being William Smith and Caroline Southwood. In 1802 he won a scholarship[1] to the Bristol Baptist College to train as a minister, but in 1807 funds were abruptly withdrawn, on the grounds that he was 'entertaining opinions widely different from us on most of the doctrines we consider to be essential to Evangelical Religion'.[1] At 19 years old he was already showing the courage and independence of mind that were to characterise his life, however it led to a break with his parents who never spoke to him again.[1] Over the following four years Smith turned to Unitarianism, influenced by William Blake, a minister at Crewkerne, Somerset: Blake put him in touch with John Prior Estlin at Lewin's Mead, Bristol. Another friend, and Unitarian convert from Baptism who became a physician, was Benjamin Spencer.[2] These associations and friendships drew him into the centre of 19th Century reform.[1]

Medical man

Smith entered the University of Edinburgh in October 1812, and in November took over the Unitarian congregation meeting in Skinners' Hall, Canongate, which had stayed together without a minister since the death in 1795 of James Purves; he became known as a powerful preacher and raised the attendance sharply. In June 1813 he began a course of fortnightly evening lectures on universal restoration; these were published in 1816 and made him a literary reputation.[3][4] Also in 1813 he founded the Scottish Unitarian Association, with James Yates,[5] which brought Smith into contact with the Unitarian Lady Gillies and her nieces Mary and Margaret Gillies who would play a large part in his later life.[1]

In 1816 he took his M.D. degree, and began to practice at Yeovil, Somerset, also becoming minister at a chapel in that town, but moved in 1820 to London, devoting himself mainly to medicine.[6]

Public health

In 1824 Smith was appointed physician to the London Fever Hospital.[6]8 The following year he began to write papers on public health. His post gave him the opportunity to study diseases of poverty. In the late 1830s, with Neil Arnott and James Phillips Kay, he was one of the first doctors brought in to report to the Poor Law Commission.[7] In 1842 he was one of the founders of an early housing association, the Metropolitan Association for Improving the Dwellings of the Industrious Classes.[8]

Smith was a close ally on public health matters with Edwin Chadwick, and like him supported the miasma theory.[9] From 1848 to 1854 they worked closely together at the General Board of Health.[7] But the appointment of Lord Seymour made their work very difficult, despite the support of Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury.[10]

Smith was frequently consulted in fever epidemics and on sanitary matters by public authorities. His reports on quarantine (1845), cholera (1850), yellow fever (1852), and on the results of sanitary improvement (1854) were of international importance.[6]

Bentham dissection

Southwood Smith was a close friend of Jeremy Bentham and his secretary Edwin Chadwick.[1] He had a particular interest in applying his philosophical beliefs to the field of medical research. In 1827 he published The Use of the Dead to the Living, a pamphlet which argued that the current system of burial was a wasteful use of bodies that could otherwise be used for dissection by the medical profession. Bentham attached a paper, written in 1830 to his will instructing Southwood Smith to create the auto-icon.[1] It stated:

'My body I give to my dear friend Dr Southwood Smith to be disposed of in a manner hereinafter mentioned, and I direct ... he will take my body under his charge and take the requisite and appropriate measures for the disposal and preservation of the several parts of my bodily frame in the manner in the paper annexed to this my will and at the top of which I have written Auto Icon.

The skeleton he will cause to be put together in such a manner that the whole figure may be seated in a chair usually occupied by me when living, in the attitude in which I am sitting while engaged in thought in the course of time occupied in writing.

I direct that the body thus prepared shall be transferred to my executor. He will cause the skeleton to be clad in one of the suits of black occasionally worn by me. The body so clothed, together with the chair and the staff in my later years borne by me, he will take charge of, and for containing the whole apparatus he will cause to be prepared an appropriate box or case, and will cause to be engraved in conspicuous characters on a plate to be affixed thereon and also on the labels on the glass case in which the preparations of the soft parts of my body shall be contained, ... my name at length with the letters ob: followed by the day of my decease.

If it should so happen that my personal friends and other disciples should be disposed to meet together on some day or days of the year for the purpose of commemorating the founder of the greatest happiness system of morals and legislation, my executor will from time to time cause to be conveyed in the room in which they meet the said box or case with the contents therein, to be stationed in such part of the room as to the assembled company shall seem meet.' – Queen's Square Place, Westminster, Wednesday 30 May 1832.[1]

Bentham's wish to preserve his dead body was consistent with his philosophy of utilitarianism. In his essay Auto-Icon, or the Uses of the Dead to the Living, Bentham wrote, "If a country gentleman has rows of trees leading to his dwelling, the auto-icons of his family might alternate with the trees; copal varnish would protect the face from the effects of rain."[11] On 8 June 1832, two days after his death, invitations were distributed to a select group of friends, and on the following day at 3 p.m., before the dissection, Southwood Smith delivered a lengthy oration over Bentham's remains in the Webb Street School of Anatomy & Medicine in Southwark, London. In the oration Smith argued that:"If, by any appropriation of the dead, I can promote the happiness of the living, then it is my duty to conquer the reluctance I may feel to such a disposition of the dead, however well-founded or strong that reluctance may be".

Afterward, the skeleton and head were preserved and stored in a wooden cabinet called the "Auto-icon", with the skeleton padded out with hay and dressed in Bentham's clothes. From 1833 it stood in Southwood Smith's Finsbury Square consulting rooms until he abandoned private practice in the winter of 1849-50 when it was moved to 36 Percy Street, Margaret Gillies' studio, who made studies of it. In March 1850 Southwood Smith offered the auto-icon to Henry Brougham who readily accepted it for UCL.[12]

Smith's lobbying helped lead to the 1832 Anatomy Act, the legislation which allowed the state to seize unclaimed corpses from workhouses and sell them to surgical schools. While this act is credited with ending the practice of grave robbery, it has also been condemned as discriminatory against the poor.

Works

In 1830 Smith published A Treatise on Fever, which became a standard authority on the subject. In this book he established a direct connection between the impoverishment of the poor and epidemic fever.[6] The underlying theory opposed contagion as a mechanism of spread of disease, and postulated no pathogen that was airborne; it argued that the exclusion of "pure air" could suffice to create mortal disease.[13]

Family

Smith married twice, firstly in 1808, to Anne Read, the daughter of a prominent Bristol tradesman. Anne died of fever four years later, at age 24, leaving Smith a widower with two young daughters, Caroline and Emily.[14] His second marriage was to Mary, daughter of John Christie of Hackney, and they had three children,[1] including his only son, Herman (died 23 July 1897, aged 77).[15] The second marriage was not successful and soon Mary and her three children moved abroad. Miranda and Octavia Hill were his granddaughters, among the five daughters of his eldest, Caroline (c. 1809–1902), who married James Hill, merchant in 1835, and as Caroline Southwood Hill was known as a writer and educationalist. His other daughter, Emily (c. 1810-1872), moved to Florence, Italy.[16][17][1]

Smith had separated from his second wife by the end of the 1830s, and for the rest of his life he lived quietly with the artist Margaret Gillies.[18] Along with his son Herman and daughter Emily they visited Wisbech in June 1836 and dined with Caroline and the actor William Macready, who was appearing as Hamlet in the Georgian Angles Theatre owned by James and Caroline. They also owned a school they built in front of the theatre. Following his son-in-law James Hill's second bankruptcy in 1840, his three-year-old granddaughter Gertrude Hill (1837–1923) came to live with him. In the 1861 census the household lived at Heath House, Weybridge and consisted of Thomas Smith 72, Mary Gillies 62, Margaret Gillies 56, his son Herman Smith 40, wine merchant, his granddaughter Gertrude Hill, 23 lady, and a cook and a housemaid.

Later life

In his 70th year Smith travelled abroad for the first time to Milan, Italy to examine the irrigation works. Two years later, on a visit to his daughter Emily in Florence, he caught a chill and died there on 10 December 1861.[1] He is interred there in the English Cemetery of Florence; his tombstone, an obelisk with a cameo portrait, was sculpted by Joel Tanner Hart. His daughter Emily, who died in 1872, is buried beside him.

Further reading

- Cook G. C. Thomas Southwood Smith FRCP (1788–1861): leading exponent of diseases of poverty, and pioneer of sanitary reform in the mid-nineteenth century. J. Med. Biog. (2002) 10(4): 194–205 doi:10.1177/096777200201000403

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Raphael, Isabel (2009). "Southwood Smith: his extraordinary life and family". Camden History Review. 33.

- ↑ Webb, R. K. "Smith, Thomas Southwood". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25917. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Gordon 1898, pp. 135–136.

- ↑ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ↑ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- 1 2 3 4 Chisholm 1911.

- 1 2 Amanda J. Thomas (2010). The Lambeth cholera outbreak of 1848-1849: the setting, causes, course and aftermath of an epidemic in London. McFarland. pp. 55–6. ISBN 978-0-7864-3989-8. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ↑ The Medical Times and Gazette. 1861. p. 652. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ↑ Margaret Stacey (1 June 2004). The Sociology of Health and Healing. Taylor and Francis. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-203-38004-8. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ↑ Samuel Edward Finer (1952). The Life and Times of Sir Edwin Chadwick. Methuen. pp. 424–5. ISBN 978-0-416-17350-5. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ↑ Forbes, Malcolm (1988). They Went That-a-way. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 28. ISBN 0-671-65709-7.

- ↑ Hayes, David (2009). "From Southwood Smith to Octavia Hill: a remarkable family's Camden years". Camden History Review. 33: 9.

- ↑ Andrew Cunningham (19 July 1990). The Medical Enlightenment of the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-521-38235-9. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ↑ Dorothy Porter (January 1993). Doctors, politics and society: historical essays. Rodopi. p. 53. ISBN 978-90-5183-510-6. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ↑ Gordon 1898, p. 137.

- ↑ Gertrude Hill Lewes (22 December 2011). Dr Southwood Smith: A Retrospect. Cambridge University Press. p. 9 notes. ISBN 978-1-108-03798-3. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ↑ Gleadie, Kathyn. "Hill, Caroline Southwood". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/60328. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Yeldham, Charlotte. "Gillies, Margaret Southwood". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10745. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Attribution:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gordon, Alexander (1898). "Smith, Thomas Southwood". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 53. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 135–137.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gordon, Alexander (1898). "Smith, Thomas Southwood". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 53. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 135–137. - This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Smith, Thomas Southwood". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 270.

External links

- Works by or about Thomas Southwood Smith at Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Southwood Smith at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)