| Part of a series on |

| Ethnicity in British Columbia |

|---|

|

|

|

|

The South Asian community in British Columbia was first established in 1897. The first immigrants originated from Punjab, British India, a northern region and state in modern-day India and Pakistan. Punjabis originally settled in rural British Columbia at the turn of the twentieth century, working in the forestry and agricultural industries.

As their numbers grew, anti-"Hindu" sentiment increased among the Europeans living in the province thus preventing them from voting in 1908. Originally, Indian settlement was predominantly male; large numbers of women and children began arriving in the mid-20th century. In 1947, South Asians were given the right to vote, therefore permitting their entry into British Columbian political life.

In the late 20th century, many South Asians transitioned from living in rural areas of the province into living in urban areas as the economic vitality of the forestry industry declined.

History

1897 to 1906

The first persons of South Asian origin to visit British Columbia were soldiers transiting from India to the United Kingdom. They went through in 1897 and 1902, the former during the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria and the latter when Edward VII was crowned as king.[3] The Punjabis who did not stay in Canada returned home and spread the word about life in Canada.[4] Additional British Indians, soldiers stationed in East Asia, including Hong Kong and Shanghai, traveled after the Boxer Rebellion period. Many of them arrived in Canada.[5]

The Indians who had participated in the Diamond Jubilee and Chinese both had given positive information regarding Canada, convincing Indians in China to immigrate to Canada.[6] Some of these early pioneers remained in the province and by 1900 were around 100 South Asians in the Lower Mainland.[3] Most of these early settlers were male Sikh Punjabis thus becoming the first South Asian-origin group to move to Canada. They settled in British Columbia with the wish to find jobs.[7]

.jpg.webp)

At the turn of the 20th century new restrictions on Chinese immigrants caused their immigration figures to decline. Steamship lines began recruiting Indians to make up for the loss of business from the Chinese. There was a job shortage in the agricultural sector, and the Fraser River Canners' Association and the Kootchang Fruit Growers' Association asked the Canadian government to abolish immigration restrictions on persons working as domestic servants and agricultural workers and to allow increased immigration. Letters from persons settling in Canada gave persons still in India encouragement to move to Canada, and there was an advertising campaign to promote British Columbia as an immigration destination.[8]

Hoshiarpur and Jullundur in Punjab were the areas from which the largest groups of initial immigrants originated. This was due to a crisis in the region at the time; peasants in Jullundur became tenants had gone into debt after losing control of their land due to the concept of private property and cash taxation established during British colonization.[9] Facing rising debts, many individuals emigrated from Jullundur and Hoshiarpur to Canada.[10] Other three major points of origin were Amritsar, Ferozpur, and Ludhiana.[11] The vast majority came from the Doaba and Malwa areas while relatively few came from Majha and some emigrated from the United States and other areas in the British Commonwealth. In the coming decades, the differentiation between Doaba and Malwa-originating persons continued to be an issue even as it had decreased in importance in the Punjab".[12]

.jpg.webp)

William Lyon Mackenzie King, the Deputy Minister of Labour, concluded that, "exploitative ventures of some East Indian immigration agents in British Columbia" and "misleading literature by certain individuals" were the primary reasons why persons of Indian origin immigrated to Canada to be the most important causes of Indian immigration to Canada; King had been tasked to discover why persons of Indian origin were immigrating to Canada.[13] However, the report did not take into account other factors which convinced people to leave Punjab,[14] including the promotion of social mobility and a lack of stratification in Sikhism as well as a lack of stigma against migration.[15]

A notable moment in early South Asian Canadian history in British Columbia was in 1902 when Punjabi Sikh settlers first arrived in Golden, British Columbia to work at the Columbia River Lumber Company.[16] This was a theme amongst most early Punjabi settlers in Canada to find work in the agricultural and forestry sectors in British Columbia.[17] Punjabis became a prominent ethnic group within the sawmill workforce in British Columbia almost immediately after initial arrival to Canada.[18]

The early settlers in Golden built the first Gurdwara (Sikh Temple) in Canada and North America in 1905,[19][20] which would later be destroyed by fire in 1926.[21] The second Gurdwara to be built in Canada was in 1908 in Kitsilano (Vancouver), aimed at serving a growing number of Punjabi Sikh settlers who worked at nearby sawmills along False Creek at the time.[22] The Gurdwara would later close and be demolished in 1970, with the temple society relocating to the newly built Gurdwara on Ross Street, in South Vancouver. The third Gurdwara to be built in Canada was the Gur Sikh Temple, located in Abbotsford, British Columbia. Built in 1911, it is the oldest existing Gurdwara in the country and the continent, and was designated as a national historic site of Canada in 2002.

The first large contingent of South Asians first arrived in 1904; nearly all were Punjabi Sikhs originating from the Chinese cities of Guangzhou (Canton), Hong Kong, and Shanghai.[13][23] These first settlers began to work in the forestry industry and congregated around sawmills along the Fraser River, including settlements such as Fraser Mills and Queensborough; the former in present-day Coquitlam, with the later situated in New Westminster.[24] Small towns on Vancouver Island including Paldi were prominent sites for early South Asian settlement (primarily Punjabi Sikhs) that revolved around the sawmill industry, while a minority also found employment in agriculture in the Fraser Valley in Abbotsford. Out of these sites, today, both Queensborough and Abbotsford still retain a large South Asian community, each forming around 30% of the local population.

1907 to 1920

.jpg.webp)

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 100 | — |

| 1908 | 5,209 | +5109.0% |

| 1911 | 2,292 | −56.0% |

| 1921 | 951 | −58.5% |

| 1931 | 1,283 | +34.9% |

| 1941 | 1,343 | +4.7% |

| 1951 | 1,937 | +44.2% |

| 1961 | 4,526 | +133.7% |

| 1971 | 18,795 | +315.3% |

| 1981 | 56,210 | +199.1% |

| 1986 | 78,810 | +40.2% |

| 1991 | 118,200 | +50.0% |

| 1996 | 165,010 | +39.6% |

| 2001 | 210,420 | +27.5% |

| 2006 | 265,595 | +26.2% |

| 2011 | 313,440 | +18.0% |

| 2016 | 365,705 | +16.7% |

| 2021 | 473,970 | +29.6% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [1][25][26][27][28][29] [30][31][32]: 34 [33][34][35][36][37][38][39]: 484 [40]: 272 [41]: 2 [42]: 503 [43]: 354&356 [44][45]: 20 | ||

A large increase in Indian settlement occurred in 1906 and 1907 as over 5,000 individuals from South Asia arrived in Canada.[46][8] Many immigrants initially settled rural areas, and there they worked in Canada's forestry industry.[47][48] Many South Asians who came to British Columbia did not remain, but instead went to the United States.[49] As of 1908 there were about 5,000 persons of Indian origin in Canada.[50]

Anti-Indian sentiment among the white population increased as the numbers of South Asians increased.[13] The persons already in British Columbia had already felt anti-Chinese and anti-Japanese sentiment, which had been responsible for 1907 riots investigated by the Canadian government. Nevertheless, many Indians continued to arrive on the shores of British Columbia through 1908; in effect, this renewed the hostile feeling of the Canadian people towards East and South Asians.[51]

Kitsilano, a community straddling False Creek in Vancouver also played host to a large contingent of Sikh settlers and in 1908 was the site of the second-oldest Gurdwara (Sikh temple) to be constructed in Canada and North America, three years after the oldest Gurdwara in the country and continent opened in Golden. The third-oldest Gurdwara (Gur Sikh Temple) to be built in Canada and North America, and the oldest existing Gurdwara in the country and continent was built in Abbotsford in 1911. Later, the fourth Gurdwara to be built Canada was established in 1912 in Victoria on Topaz Avenue, while the fifth soon was built at the Fraser Mills (Coquitlam) settlement in 1913, followed a few years later by the sixth at the Queensborough settlement (1919),[52][53][54] and the seventh at the Paldi settlement (1919).[55][56][57][58]

Europeans stated that the increase in Indians during this period was depressing wages, and the employment situation became a job shortage. Trade unions and the Victoria Trade and Labour Council protested the immigration influx.[8] The authorities acted due to pressure from white persons; the federal government instituted immigration restrictions against persons of Indian origin.[59] Later, Indo-Canadians opposed a 1909 attempt by British authorities to move those in British Columbia to British Honduras, modern day Belize.[23]

In 1908 the British Columbia government passed a law preventing East Indian men from voting. Because eligibility for federal elections originated from provincial voting lists, East Indian men were unable to vote in federal elections.[60] Restrictions were placed despite the British government's concerns that anti-British sentiment would grow back in India, and that anti-British forces would take advantage of these sentiments.[59] In addition the Canadian government had enacted a $200 head tax and de facto blocked significant immigration from India by establishing the continuous journey regulation - a rule requiring immigrants to take a continuous journey from their country of origin to Canada. At the time there was no continuous route between India and Canada. There were also measures that prevented wives and children of Indians already resident in Canada from going to Canada. Beginning in 1909 the annual numbers of Indians immigration to Canada did not go above 80 and this did not change until the mid-20th century immigration reforms.[50]

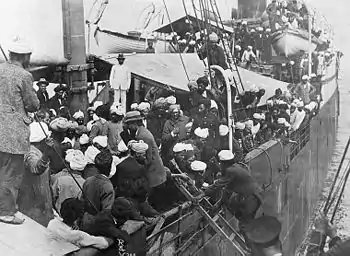

Throughout much of the community's history it was mostly made up of men due to restrictions on the importation of difficulties in bringing women and children. This era was referred to as the "bunkhouse life",[61] as the men were unable to establish families.[62] As a result, by 1912 there were fewer than 2,400 persons of Indian origin residing in Canada; this decline was a result of the 1908 restrictions.[50] South Asians continued the attempt to immigrate to Canada; the Komagata Maru Incident, involving a ship with 376 Punjabi Sikh, Muslim and Hindus being denied entry into British Columbia, occurred in 1914.[63]

The Paldi mill colony was established by Punjabi immigrants who had invested in the Mayo Lumber Company in 1916.[64] Soon later, a count revealed the declining population of South Asians throughout the province; numbers revealed there were 1,100 Indo-Canadians in British Columbia.[59] By 1919, the Canadian government passed the ban against immigration of wives and children of Indians already in Canada. The British Indian authorities had pressured the Canadian government to lift the ban.[50]

1921 to 1980

By 1923 Vancouver became the primary cultural, social, and religious centre of British Columbia Indo-Canadians and it had the largest Indian-origin population of any city in North America.[65] Victoria became another centre of Indo-Canadian business activity and members of the ethnic group also settled Coombs, Duncan, Fraser Mills, New Westminster, and Ocean Falls.[66] As of 1923 rural areas that received Indo-Canadian settlement included those in the Fraser Valley and Vancouver Island.[67]

During the 1920s, the South Asian population growth leveled off; by 1929, there were only around 1,000 South Asians British Columbia; most were Punjabis with 80% being Sikh and about 20% were Hindu or Muslim.[68] In the post-World War I period about half of the Punjabis in British Columbia moved to India as they were unable to find work. Many Punjabis left during the Great Depression in the 1930s after additional sawmills closed.[64] Many remaining Punjabis were employed at sawmills, particularly those operated by Punjabis, and logging camps.[69]

The Canadian authorities passed additional immigration restrictions in the 1930s.[70] This created a population stagnation in the following decade during the great depression; by 1940, the estimated number of those of South Asian origins in British Columbia was 1,100. Vancouver and several logging camps housed the majority of Indians at that time.[61] Of all Indian immigrants to Canada, the percentage of those moving to British Columbia in particular was around 90% until the 1950s.[71]

After the independence of India in 1947 and the beginning of regulation of immigration from India in 1951 the numbers of women and children increased.[61] This was the first significant immigration from India to Canada since the restrictions were passed in 1908.[50] Persons of South Asian origin in BC were given the right to vote in 1947.[72] The Canadian government adopted new immigration rules in 1962,[70] ending the quota-by-country system. The Immigration Act of 1967 established a new point system for determining immigration eligibility.[73]

By the 1960s Indo-Canadians who came after 1947 outnumbered those who came before 1947 (with most of the latter group coming before 1920).[74] An increase in the forestry and fishing sectors lead to Punjabi persons moving to the Skeena Country in the 1960s and 1970s. Once the fishery and forestry industries downturned in the following decades, South Asians began moving to urban areas.[47]

The South Asian population would begin growing at an accelerating rate through the 1960s. By 1971, British Columbia had 18,795 residents of South Asian origins; the number of non-Sikhs had increased since the late 1960s. Nevertheless, Punjabi Sikhs still retained a strong majority among the South Asian population in the province; at the time, about 80 per cent of South Asians in British Columbia were Sikh with 90% belonging to the Jat people.[23] However, since the census had no separate category for Punjabi Sikhs, no accurate figure for them existed with Sikh temples in New Westminster and Vancouver estimating that British Columbia had about 15,000-20,000 Sikhs with most living in the southwest of the province.[12][75] By this time, over half of the total South Asians residing in the province lived in Metro Vancouver.[76][77]

Through the 1970s, the South Asian population in the province began to get more diverse fueled by an increase in immigration of persons of South Asian origin who were not Sikhs.[23] Nevertheless, the Sikh population continued to grow throughout the province and by the mid-1980s, the estimated population exceeded 40,000 in Greater Vancouver and 20,000 in other areas of British Columbia for a total of over 60,000.[78]

1981 to present

In 1986, following the British Columbia provincial election, Moe Sihota became the first Canadian of South Asian ancestry to be elected to provincial parliament. Sihota, who was born in Duncan, British Columbia in 1955, ran as the NDP Candidate in the riding of Esquimalt-Port Renfrew two years after being involved in municipal politics, as he was elected as an Alderman for the City of Esquimalt in 1984.

Inderjit Singh Reyat, convicted of being involved in the Air India Flight 182 bombing,[79] was a resident of Duncan.[80] The "Duncan Blast", a test explosion, occurred outside of Duncan,[81] on June 4, 1985. Reyat was present at the test explosion.[82] The bomb that went on AI182 was first placed on a connecting flight that departed Vancouver.[83]

While wide-scale urbanization of the South Asian community had been ongoing for decades, the most statistically significant populations nonetheless continued to exist across rural parts of the province through the late 20th century; a legacy of previous waves of immigration and settlement patterns that existed earlier in the 20th century, as Punjabi Sikh Canadians and new immigrants continued to seek employment in the provincial forestry sector at sawmills throughout the island and interior. During the period between 1981 and 1996, small towns including Fort St. James (South Asians formed 22 percent of the total population), Quesnel (14 percent), Lake Cowichan (13 percent), Merritt (13 percent), Williams Lake (12 percent), Tahsis (10 percent), Golden (10 percent), 100 Mile House (10 percent), Squamish (9 percent), and Lillooet (9 percent) had the largest South Asian concentrations in Canada.[35][84][85][86][87][88]

The 1991 Statistics Canada census counted over 67,495 people in British Columbia natively spoke Punjabi.[91] From January 1992 through March of the same year, 7,121 Indian immigrants settled in British Columbia. The number of Indian immigrants to British Columbia at that time made up around 25% of all Indian immigration to Canada with Indian immigration accounting for 10% of the total immigration to British Columbia. This made India the third most common origin of immigrants to the province. Over half of the new Indian immigrants settled in Greater Vancouver.[73] Meanwhile in the mid-1990s, the number of jobs in forestry decreased, thus threatening the livelihood of many South Asians across the province. Eventually the British Columbian forest sector collapsed in the early 2000s; this prompted many South Asians - mainly Punjabi Sikhs - residing in sawmill-based towns throughout the interior to relocate to urban areas.[92]

As of the Statistics Canada 2001 Census there were 210,420 Indo-Canadians in British Columbia. In terms of ethnic origins, of BC's Indo-Canadians, 183,650 were East Indian, 16,565 were Punjabi, 6,270 were Pakistani, 6,160 were South Asian, n.i.e., 2,295 were Sri Lankan, 1,185 were Tamil, 560 were Bangladeshi, 450 were Sinhalese, 305 were Nepali, 295 were Bengali, 250 were Goan, 205 were Gujarati, and 55 were Kashmiri. As of the same census, a total of 163,340 Indo-Canadians lived in the Vancouver region.[93]

As of the 2010s there has been ongoing controversy regarding the proposed deportation of Surjit Bhandal. Her nephew, Jasminder Bhandal of Victoria, is attempting to keep her in Canada.[94] The woman lived in Langford.[95]

Demography

Population

| Year | Population | % of total population |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 [3] |

>100 | 0.056% |

| 1908 [45]: 20 |

5,209 | 1.586% |

| 1911 [43]: 354&356 [45]: 20 |

2,292 | 0.584% |

| 1921 [43]: 354&356 [45]: 20 |

951 | 0.181% |

| 1931 [42]: 503 [45]: 20 |

1,283 | 0.185% |

| 1941 [40]: 272 [41]: 2 [45]: 20 |

1,343 | 0.164% |

| 1951 [39]: 484 [45]: 20 |

1,937 | 0.166% |

| 1961 [38][45]: 20 |

4,526 | 0.278% |

| 1971 [37][45]: 20 |

18,795 | 0.86% |

| 1981 [35] |

56,210 | 2.071% |

| 1986 [32]: 34 [33][34] |

78,810 | 2.766% |

| 1991 [30][31] |

118,200 | 3.64% |

| 1996 [29] |

165,010 | 4.472% |

| 2001 [28] |

210,420 | 5.439% |

| 2006 [27] |

265,595 | 6.519% |

| 2011 [26] |

313,440 | 7.248% |

| 2016 [25] |

365,705 | 8.019% |

| 2021 [1] |

473,970 | 9.641% |

South Asian settlement in British Columbia began in the late 19th century; by 1901, there were upwards of 100 who had entered the province. This number grew rapidly and peaked at 5,209 in 1908 before declining to around 1,000 in 1921 and later stagnating through to the early 1950s.[45]: 20 Prior to the elimination of racial restrictions to Canada in 1961, the South Asian population in British Columbia had grown to approximately 4,530.[45]: 20

According to the 2021 Canadian census, the South Asian Canadian population in British Columbia stood at 473,970 persons, accounting for just over 9.6% of the total provincial population.[1] The growth of the population is primarily attributed to sustained invitations of immigration from South Asian nations. The vast majority of South Asian immigrants who immigrate to and reside in British Columbia trace their roots to the Punjab region of India and Pakistan; the province has the largest Punjabi population in Canada. According to a 2022 study conducted by Statistics Canada, British Columbians with South Asian ancestry will grow to between 807,000 and 1.1 million by 2041 or 13.4 to 14.7 percent of the provincial population overall.[96][97]

National origins

| 2016[25] | 2011[26] | 2006[27] | 2001[28] | 1996[29] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | |

| India[lower-alpha 4] | 351,495 | 96.11% | 301,085 | 96.06% | 253,205 | 95.34% | 202,205 | 96.1% | 161,675 | 97.98% |

| Pakistan | 12,585 | 3.44% | 9,770 | 3.12% | 7,975 | 3% | 6,270 | 2.98% | 4,180 | 2.53% |

| Sri Lanka | 5,710 | 1.56% | 5,215 | 1.66% | 4,150 | 1.56% | 2,295 | 1.09% | 1,430 | 0.87% |

| Bangladesh | 1,840 | 0.5% | 1,210 | 0.39% | 840 | 0.32% | 560 | 0.27% | 245 | 0.15% |

| Nepal | 1,495 | 0.41% | 1,255 | 0.4% | 570 | 0.21% | 305 | 0.14% | N/A | N/A |

| Bhutan | 120 | 0.03% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Total South Asian Canadian population in British Columbia | 365,705 | 100% | 313,440 | 100% | 265,595 | 100% | 210,420 | 100% | 165,010 | 100% |

- Note: Totals exceed 100% due to multiple origin responses.

Presently, the majority of the South Asian population in British Columbia remains of Punjabi heritage, predominantly of the Sikh faith.

According to the 2021 Canadian census, the Punjabi population in British Columbia is 315,000,[98][lower-alpha 5] representing approximately 6.4 percent of the total population. Furthermore, as per the 2021 census, 92 percent of Punjabis in British Columbia were Sikh, with the remaining 8 percent being Hindu, Muslim or adherents of another faith.[lower-alpha 6]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 45,000 | — |

| 1986 | 54,075 | +20.2% |

| 1991 | 77,830 | +43.9% |

| 1996 | 112,365 | +44.4% |

| 2001 | 142,785 | +27.1% |

| 2006 | 184,590 | +29.3% |

| 2011 | 213,315 | +15.6% |

| 2016 | 244,485 | +14.6% |

| 2021 | 315,000 | +28.8% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [98][103][104][105][106][107][108][102][100][101] | ||

| Year | Proportion % |

|---|---|

| 1981 | 80.06 |

| 1986 | 68.61 |

| 1991 | 65.85 |

| 1996 | 68.10 |

| 2001 | 67.86 |

| 2006 | 69.50 |

| 2011 | 68.06 |

| 2016 | 66.85 |

| 2021 | 66.46 |

While the heavy concentration of Punjabis in Canada relative to their proportion in South Asia continues to exist, it is more pronounced in British Columbia compared with other provinces, owing to historical settlement patterns as Punjabis were the first South Asian-origin group to settle in the province.[45] Nonetheless, despite the large proportion of Punjabis in the province, the South Asian population in British Columbia remains diverse; minority populations of Gujaratis, Bengalis, and individuals from South India as well as East African Ismailis, and Fijian Indians are present.[45]

Language

As of 2021, the most prominent South Asian languages spoken in British Columbia include Punjabi, Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu) and Gujarati.[98]

In particular, the Punjabi speaking population in British Columbia has witnessed constant growth over recent decades. In 1991, nearly 78,000 people in British Columbia spoke Punjabi;[108] by 1996 this number grew to approximately 112,000.[107] By 2001, roughly 143,000 people in the province spoke Punjabi,[106] climbing to around 185,000 in 2006,[105] to 213,000 in 2011,[104] with further growth to about 244,000 by 2016.[103]

As of 2021, British Columbia has about 315,000 Punjabi speakers, accounting for roughly 6.4% of the total provincial population.[98] Punjabi is also the third most known language across British Columbia, after English and French.[98] Due to the prominence of Punjabi in British Columbia, some provincial and federal institutions in some municipalities across the province have literature and office signage using the Gurmukhi script.[109]

Knowledge of language

Many South Asian Canadians speak Canadian English or Canadian French as a first language, as many multi-generational individuals do not speak South Asian languages as a mother tongue, but instead may speak one or multiple[lower-alpha 8] as a second or third language.

| British Columbia[98] | Metro Vancouver[110] | Fraser Valley[111] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 5,000,879 | 2,642,825 | 324,005 | |||

| Number of responses | 4,915,940 | 2,607,010 | 317,670 | |||

| 406,380 | 8.27% | 317,790 | 12.19% | 49,805 | 15.68% | |

| 315,000 | 6.41% | 239,205 | 9.18% | 47,065 | 14.82% | |

| 160,730 | 3.27% | 132,450 | 5.08% | 10,295 | 3.24% | |

| 134,950 | 2.75% | 110,485 | 4.24% | 8,950 | 2.82% | |

| 25,780 | 0.52% | 21,965 | 0.84% | 1,345 | 0.42% | |

| 14,340 | 0.29% | 12,615 | 0.48% | 305 | 0.1% | |

| 6,565 | 0.13% | 5,330 | 0.2% | 130 | 0.04% | |

| 3,440 | 0.07% | 3,040 | 0.12% | 70 | 0.02% | |

| 3,560 | 0.07% | 2,930 | 0.11% | 75 | 0.02% | |

| 2,925 | 0.06% | 2,745 | 0.11% | 50 | 0.02% | |

| 2,445 | 0.05% | 1,645 | 0.06% | 105 | 0.03% | |

| 770 | 0.02% | 655 | 0.03% | 0 | 0% | |

| 650 | 0.01% | 505 | 0.02% | 20 | 0.01% | |

| 185 | 0% | 140 | 0.01% | 20 | 0.01% | |

| 180 | 0% | 140 | 0.01% | 10 | 0% | |

| 100 | 0% | 95 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |

| 55 | 0% | 55 | 0% | 0 | 0% | |

|

1,645 | 0.03% | 1,395 | 0.05% | 100 | 0.03% |

| 20,585 | 0.42% | 16,585 | 0.64% | 630 | 0.2% | |

| 9,740 | 0.2% | 8,440 | 0.32% | 125 | 0.04% | |

| 6,765 | 0.14% | 4,615 | 0.18% | 395 | 0.12% | |

| 4,860 | 0.1% | 3,940 | 0.15% | 160 | 0.05% | |

| 1,620 | 0.03% | 1,425 | 0.05% | 15 | 0% | |

| 205 | 0% | 180 | 0.01% | 0 | 0% | |

|

45 | 0% | 40 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

Religion

In 1971, the Canadian government introduced a policy of multiculturalism, and this resulted in the South Asian community establishing urban places of worship using traditional architecture styles.[112]

The 2001 Canadian census found that the religious breakdown of Canadians with South Asian ancestry in British Columbia was 63.3% Sikhism, 14.2% Hinduism, 11.6% Islam, 5.8% Christianity, 3.9% irreligious, 0.5% Buddhism, 0.2% Zoroastrianism, 0.05% Indigenous, 0.04% Judaism, 0.04% Jainism, 0.01% Baháʼí, and 0.1% other.[113]

As of the 2001 Statistics Canada there were 135,305 Sikhs and 31,500 Hindus in British Columbia. 99,005 Sikhs and 27,405 Hindus were in Metro Vancouver.[93]

The 2011 Canadian census found that the religious breakdown of Canadians with South Asian ancestry in British Columbia was 63.4% Sikhism, 13.9% Hinduism, 10.1% Islam, 6.1% irreligious, 5.4% Christianity, 0.6% Buddhism, 0.04% Judaism, and 0.5% other.[114]

| 2021[2] | 2011[114] | 2001[113][115] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | % | Population | % | Population | % | |

| Sikhism | 287,940 | 60.8% | 198,785 | 63.4% | 133,190 | 63.3% |

| Hinduism | 75,935 | 16% | 43,705 | 13.9% | 29,880 | 14.2% |

| Islam | 44,690 | 9.4% | 31,510 | 10.1% | 24,350 | 11.6% |

| Irreligion | 38,560 | 8.1% | 19,170 | 6.1% | 8,450 | 4% |

| Christianity | 21,740 | 4.6% | 16,770 | 5.4% | 12,410 | 5.9% |

| Buddhism | 3,100 | 0.7% | 1,860 | 0.6% | 1,105 | 0.5% |

| Jainism | 720 | 0.2% | N/A | N/A | 85 | 0.04% |

| Zoroastrianism | 510 | 0.1% | N/A | N/A | 475 | 0.2% |

| Judaism | 150 | 0.03% | 135 | 0.04% | 90 | 0.04% |

| Baháʼí | 120 | 0.03% | N/A | N/A | 30 | 0.01% |

| Indigenous | 0 | 0% | N/A | N/A | 95 | 0.05% |

| Other | 505 | 0.1% | 1,505 | 0.5% | 135 | 0.1% |

| Total responses | 473,970 | 100% | 313,440 | 100% | 210,295 | 99.9% |

| Total South Asian Canadian population in British Columbia | 473,970 | 100% | 313,440 | 100% | 210,420 | 100% |

Sikhism

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 95 | — |

| 1911 | 2,178 | +2192.6% |

| 1921 | 903 | −58.5% |

| 1931 | 1,219 | +35.0% |

| 1941 | 1,276 | +4.7% |

| 1951 | 1,840 | +44.2% |

| 1981 | 40,940 | +2125.0% |

| 1991 | 74,545 | +82.1% |

| 2001 | 135,305 | +81.5% |

| 2011 | 201,110 | +48.6% |

| 2021 | 290,870 | +44.6% |

| Source: Statistics Canada [99][117][118][119][120] [39]: 484 [40]: 272 [41]: 2 [42]: 503 [43]: 354&356 [45]: 20 | ||

The ability to freely practice the Sikh religion is the reason why many Sikhs immigrated to Canada.[121] Many of the earliest gurdwaras were built at "mill colonies." Often they were built on-site because there were difficulties in getting transportation to other places. The first gurdwara established in a mill colony was in Maillardville, situated in Fraser Mills on the south slope of Coquitlam.[122] Mill colony gurdwaras were segregated from mainstream Canadian society.[123] Once the mill colonies were disestablished, the gurdwaras often went with them. For instance, the Burquitlam gurdwara had been disestablished.[122]

Many of the early urban gurdwaras were operated by the Khalsa Diwan Society (KDS), headquartered in Vancouver, while the small town gurdwaras had separate management.[122] The first gurdwara in Vancouver opened in 1908 by the KDS.[124] In 1911 the KDS opened a gurdwara in Abbotsford, and it subsequently opened gurdwaras in New Westminster and Victoria.[122] Many gurdwaras in urban areas were in proximity to Sikh communities or mill camps.[122]

Cities in British Columbia which had gurdwaras by 1920 included Abbotsford, Fraser Mills, Golden, Nanaimo, New Westminster, Paldi, Vancouver, and Victoria.[125] The main Sikh temple in Victoria, as of 1929, was a painted wooden building on Topaz Avenue. That year Perry wrote that the temple was "comparing not unfavourably with many Christian churches" in Victoria but that it was "crude and tawdry, perhaps, as compared with" the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) in Amritsar.[126]

In 1953, tensions between more religious Sikhs (often new arrivals), and more Westernized Sikhs (those that had adopted western standards, such as clothing or Anglicization of names), resulted in the Akali Singh Society being established in Vancouver and Victoria to preserve orthodox Sikhism,[123][122] opening another temple in Port Alberni by 1973.[127] A gurdwara in Victoria independent of both Akali Singh and the KDS was opened by 1973.[128]

New gurdwaras opened in former churches in rural British Columbia in the 1970s. This occurred due to the general increase in Sikh immigration. The expansion of the Sikh community in British Columbia continued into the 1980s.[123] By 1973 the cities with Khalsa Diwan Society temples were Abbotsford, Mesachie Lake, New Westminster, Paldi, Port Alberni, and Vancouver.[61] However the New Westminster Khalsa Diwan became its own Sikh society the following year.[45]: 18 In 1975 the Khalsa Diwan Society of Abbotsford also separated, as the title of the Abbotsford gurdwara was transferred to the separated entity. The Abbotsford Sikhs wanted to have local control over their gurdwara, the Gur Sikh Temple.[129] In the mid-1970s, Ames and Inglis stated that there are British Columbia Sikhs who do not actively participate in religious ceremonies but that "Few if any Sikhs have converted to Christianity".[128]

Many smaller Indo-Canadian communities have two gurdwaras. These communities include Kamloops, Prince George, and Terrace. A 1997 disagreement regarding a dining hall in a Surrey gurdwara resulted in the Sikh community being split into two.[130]

| Metro area | 2021[99][131] | 2011[117] | 2001[118] | 1991[132][133] | 1981[134][135] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Vancouver CMA | 222,165 | 8.52% | 155,945 | 6.84% | 99,005 | 5.03% | 49,625 | 3.13% | 22,390 | 1.79% |

| Abbotsford–Mission CMA | 41,665 | 21.69% | 28,235 | 16.94% | 16,780 | 11.57% | 6,525 | 5.86% | — | — |

| Victoria CMA | 5,160 | 1.33% | 3,645 | 1.08% | 3,470 | 1.13% | 2,990 | 1.05% | 1,980 | 0.86% |

| Kelowna CMA | 4,200 | 1.92% | 1,875 | 1.06% | 990 | 0.68% | 600 | 0.54% | 305 | 0.4% |

| Prince George CA | 2,415 | 2.75% | 1,385 | 1.67% | 1,825 | 2.16% | 1,425 | 2.06% | 1,050 | 1.56% |

| Kamloops CMA | 2,070 | 1.87% | 1,150 | 1.19% | 1,395 | 1.62% | 1,065 | 1.59% | 1,095 | 1.71% |

| Chilliwack CMA | 1,675 | 1.5% | 455 | 0.5% | 230 | 0.33% | 150 | 0.25% | 145[lower-alpha 10] | 0.35% |

| Nanaimo CMA | 1,355 | 1.21% | 1,000 | 1.05% | 985 | 1.17% | 1,235 | 1.69% | 850 | 1.48% |

| Squamish CA | 1,260 | 5.26% | 910 | 5.28% | 1,580 | 10.99% | — | — | — | — |

| Penticton CA | 780 | 1.69% | 640 | 1.55% | 660 | 1.6% | 285 | 0.64% | — | — |

| Fort St. John CA | 485 | 1.71% | 55 | 0.21% | 10 | 0.06% | 60 | 0.43% | — | — |

| Vernon CA | 485 | 0.74% | 290 | 0.51% | 505 | 0.99% | 335 | 0.71% | 220[lower-alpha 10] | 0.53% |

| Duncan CA | 430 | 0.93% | 645 | 1.53% | 840 | 2.2% | 880 | 3.26% | — | — |

| Prince Rupert CA | 410 | 3.08% | 290 | 2.21% | 415 | 2.73% | 365 | 1.99% | 370[lower-alpha 10] | 2.02% |

| Terrace CA | 390 | 2% | 270 | 1.76% | 345 | 1.74% | 610 | 3.24% | 895[lower-alpha 10] | 2.77% |

| Williams Lake CA | 340 | 1.46% | 365 | 1.99% | 845 | 3.4% | 1,145 | 3.32% | — | — |

| Courtenay CA | 215 | 0.35% | 15 | 0.03% | 10 | 0.02% | 15 | 0.03% | 25[lower-alpha 10] | 0.07% |

| Port Alberni CA | 215 | 0.85% | 280 | 1.12% | 435 | 1.73% | 735 | 2.78% | 900[lower-alpha 10] | 2.77% |

| Dawson Creek CA | 205 | 1.18% | 0 | 0% | 30 | 0.17% | 0 | 0% | — | — |

| Campbell River CA | 200 | 0.5% | 40 | 0.11% | 370 | 1.1% | 250 | 0.81% | — | — |

| Quesnel CA | 185 | 0.81% | 360 | 1.65% | 720 | 2.97% | 1,000 | 4.31% | — | — |

| Cranbrook CA | 155 | 0.59% | 0 | 0% | 20 | 0.08% | 35 | 0.22% | — | — |

| Salmon Arm CA | 105 | 0.56% | 15 | 0.09% | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Trail CA | 100 | 0.72% | — | — | — | — | — | — | 65[lower-alpha 10] | 0.29% |

| Nelson CA | 75 | 0.4% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Ladysmith CA | 40 | 0.26% | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Parksville CA | 40 | 0.13% | 10 | 0.04% | 65 | 0.27% | — | — | — | — |

| Powell River CA | 40 | 0.23% | 0 | 0% | 10 | 0.06% | 65 | 0.36% | 70[lower-alpha 10] | 0.36% |

| Kitimat CA | — | — | — | — | 330 | 3.22% | 505 | 4.48% | — | — |

| Subdivision | Regional district | Percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[136] | 2011[137] | 2001[138] | 1991[119] | 1981[139][lower-alpha 10] | ||

| Surrey | Metro Vancouver | 27.45% | 22.6% | 16.29% | 8.59% | 2.7% |

| Abbotsford | Fraser Valley | 25.46% | 19.97% | 13.38% | 6.22%[lower-alpha 11] | 3.33%[lower-alpha 11] |

| Delta | Metro Vancouver | 17.93% | 10.63% | 8.57% | 4.18% | 2.11% |

| Cawston | Okanagan–Similkameen | 16.36% | 10.13% | 10.62% | 4.41%[lower-alpha 12] | 0.82%[lower-alpha 12] |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision A[lower-alpha 13] | Okanagan–Similkameen | 15.87% | 16.89% | 8.33% | 0.26% | 0.56% |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision C[lower-alpha 14] | Okanagan–Similkameen | 14.34% | 15.68% | 15.08% | 0.56% | 0% |

| Mission | Fraser Valley | 8.06% | 5.89% | 5.1% | 4.79% | 3.79% |

| McBride | Fraser–Fort George | 8.04% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Oliver | Okanagan–Similkameen | 7.56% | 5.21% | 4.48% | 0.55% | 0.9% |

| Squamish | Squamish–Lillooet | 5.35% | 5.38% | 11.18% | 5.62% | 4.75% |

| 100 Mile House | Cariboo | 5.32% | 0.84% | 1.49% | 3.71% | 6.37% |

| New Westminster | Metro Vancouver | 4.8% | 4.49% | 5.05% | 2.4% | 2.07% |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision G[lower-alpha 15] | Okanagan–Similkameen | 4.58% | 5.84% | 1.96% | 4.12% | — |

| White Rock | Metro Vancouver | 4.37% | 0.46% | 0.2% | 0.42% | 0.65% |

| Osoyoos | Okanagan–Similkameen | 4.27% | 5.57% | 0.59% | 0.89% | 0.38% |

| Langley (District) | Metro Vancouver | 3.95% | 1.91% | 1.22% | 0.46% | 0.72% |

| Langley (City) | Metro Vancouver | 3.73% | 0.14% | 0.21% | 0.64% | 0.34% |

| Prince Rupert | North Coast | 3.41% | 2.39% | 2.86% | 2.23% | 2.33% |

| Pitt Meadows | Metro Vancouver | 3.36% | 3.16% | 4.57% | 3.32% | 1.85% |

| Richmond | Metro Vancouver | 3.35% | 3.78% | 3.52% | 3.57% | 2.38% |

| Terrace | Kitimat–Stikine | 3.3% | 2.34% | 2.91% | 5.43% | 3.99% |

| Prince George | Fraser–Fort George | 3.2% | 1.96% | 2.53% | 2.06% | 1.77% |

| Williams Lake | Cariboo | 2.99% | 3.49% | 7.66% | 10.08% | 10.45% |

| Golden | Columbia-Shuswap | 2.95% | 3.13% | 4.28% | 8.13% | 5.54% |

| Saanich | Capital | 2.81% | 2.21% | 2.51% | 2.17% | 1.46% |

| Burnaby | Metro Vancouver | 2.81% | 2.9% | 2.94% | 2.15% | 1.51% |

| Merritt | Thompson–Nicola | 2.74% | 3.84% | 8.03% | 9.65% | 10.35% |

| Kelowna | Central Okanagan | 2.59% | 1.33% | 0.9% | 0.66% | 0.52% |

| Vancouver | Metro Vancouver | 2.54% | 2.85% | 2.82% | 2.78% | 2.36% |

| Fort St. John | Peace River | 2.31% | 0.3% | — | 0.43% | 0.76% |

| Port Coquitlam | Metro Vancouver | 2.21% | 2.26% | 1.58% | 1.63% | 1.03% |

| Maple Ridge | Metro Vancouver | 2.14% | 1.16% | 1.11% | 0.81% | 0.52% |

| Kamloops | Thompson–Nicola | 2.12% | 1.37% | 1.74% | 1.61% | 1.87% |

| Penticton | Okanagan–Similkameen | 2.1% | 1.75% | 2.08% | 0.95% | 0.59% |

| Quesnel | Cariboo | 1.91% | 3.61% | 7.06% | 12.04% | 13.89% |

| Smithers | Bulkley–Nechako | 1.81% | — | — | 0% | 0% |

| Chilliwack | Fraser Valley | 1.71% | 0.58% | 0.37% | 0.31% | 0.41% |

| Dawson Creek | Peace River | 1.7% | 0.62% | 0.19% | 0% | 0% |

| Central Saanich | Capital | 1.57% | 0.54% | 0.49% | 0.3% | 0% |

| View Royal | Capital | 1.51% | 2.7% | 2.34% | 2.7% | — |

| Fort St. James | Bulkley Nechako | 1.5% | 3.07% | 10.31% | 21.59% | 15.66% |

| Houston | Bulkley-Nechako | 1.49% | 4.94% | 6.98% | 7.02% | 5.48% |

| Castlegar | Central Kootenay | 1.43% | — | 0.15% | 0.23% | 0.44% |

| Sechelt | Sunshine Coast | 1.41% | — | — | 0% | 0% |

| Nanaimo | Nanaimo | 1.37% | 1.08% | 1.32% | 1.92% | 1.95% |

| Langford | Capital | 1.3% | 1.5% | 1.29% | 0.67% | 0.73% |

| Coquitlam | Metro Vancouver | 1.26% | 1.14% | 0.88% | 0.76% | 0.56% |

| Trail | Kootenay Boundary | 1.25% | — | 1.23% | 0.19% | 0.21% |

| North Saanich | Capital | 1.23% | 0.41% | 0.19% | 0.31% | 0.49% |

| North Cowichan | Cowichan Valley | 1.23% | 2.16% | 3% | 3.51% | 3.8% |

| Port Alberni | Alberni–Clayoquot | 1.2% | 1.52% | 2.42% | 3.97% | 4.33% |

| Lake Country | Central Okanagan | 1.09% | 0.75% | 0.65% | 0.25% | 0.13% |

| Summerland | Okanagan–Similkameen | 1.07% | 0.18% | 0.38% | 0.22% | 0.2% |

| Port Hardy | Mount Waddington | 1.04% | — | — | 0.89% | 0.88% |

| North Vancouver (City) | Metro Vancouver | 0.92% | 0.79% | 0.6% | 0.89% | 0.45% |

| Cranbrook | East Kootenay | 0.78% | 0.19% | 0.11% | 0.22% | 0.57% |

| Vernon | North Okanagan | 0.78% | 0.48% | 1.29% | 1.28% | 0.89% |

| Lake Cowichan | Cowichan Valley | 0.75% | 2.2% | 2.47% | 4.02% | 8.62% |

| Oak Bay | Capital | 0.68% | 0.49% | 0.2% | 0.43% | 0.12% |

| West Kelowna | Central Okanagan | 0.66% | 0.8% | 0.24% | 0.37% | 0.47% |

| Nelson | Central Kootenay | 0.65% | 0.1% | 0.16% | 0.12% | 0.11% |

| Duncan | Cowichan Valley | 0.65% | 0.56% | 1.46% | 3.21% | 1.56% |

| North Vancouver (district) | Metro Vancouver | 0.63% | 0.51% | 0.49% | 0.4% | 0.29% |

| Courtenay | Comox Valley | 0.61% | 0.04% | 0.06% | 0.04% | 0.06% |

| Campbell River | Strathcona | 0.57% | 0.13% | 1.25% | 1.19% | 2.39% |

| Fernie | East Kootenay | 0.57% | — | 0.66% | 0.61% | 1.02% |

| Salmon Arm | Columbia–Shuswap | 0.54% | 0.12% | 0.07% | 0.17% | 0.32% |

| Victoria | Capital | 0.48% | 0.41% | 0.42% | 0.52% | 0.5% |

| West Vancouver | Metro Vancouver | 0.31% | 0.27% | 0.29% | 0.04% | 0.03% |

| Kitimat | Kitimat–Stikine | 0.24% | 0.66% | 3.27% | 4.48% | 3.1% |

| Port Moody | Metro Vancouver | 0.24% | 0.55% | 0.08% | 0.37% | 0.3% |

| Lillooet | Squamish-Lillooet | — | 0.86% | 2.39% | 6% | 7.28% |

| Mackenzie | Fraser-Fort George | — | 0.42% | 7.07% | 4.58% | 4.24% |

| Elkford | East Kootenay | — | 0.4% | 1.36% | 2.74% | 3.22% |

| Tahsis | Strathcona | — | 1.56% | 2.5% | 8.29% | 10.34% |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision A[lower-alpha 1] | Thompson–Nicola | — | — | 1.59% | 3.54% | 3.88% |

| Sparwood | East Kootenay | — | — | 0.92% | 3.39% | 3.48% |

| Montrose | Kootenay-Boundary | — | — | 1.41% | 2.45% | 0.82% |

| Port McNeill | Mount Waddington | — | — | — | 1.68% | 1.84% |

Hinduism

In the past, Hindus went to Sikh gurdwaras because they lacked their own Hindu temples. Historically there were ten times the number of Punjabi Sikhs compared to Punjabi Hindus.[45]: 11

Islam

Originally Muslims participated in Sikh gurdwaras. After 1947 Indo-Canadian Muslims continued having a relationship with Sikhs but began referring to themselves as "Pakistanis" due to the Partition of India. The B.C. Muslim Association was established in 1966.[45]

Christianity

As of April 1, 2013 the Canadian Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches had Indo-Canadian outreach missions at the South Abbotsford (B.C.) MB Church and in the Fraserview area.[140]

Generation status

A large minority of British Columbians are first generation, numbering 1,657,620 people and forming 33.72% of the provincial population as of the 2021 Canadian census.[1] In comparison with the province-wide statistics, as of the 2021 Canadian census, a majority of the South Asian British Columbian community was first generation, numbering 313,570 people and forming 66.16% of the total South Asian British Columbian population.[1]

Similarly, a large minority of British Columbians are second generation, numbering 1,068,595 people and forming 21.74% of the total provincial population as of the 2021 Canadian census.[1] In comparison with the province-wide statistics, as of the 2021 Canadian census, a large minority of the South Asian British Columbian community was second generation, numbering 142,360 people or 30.04% of the total South Asian British Columbian population.[1]

A narrow plurality of British Columbians are third or more generation, numbering 2,189,720 people and forming 44.54% of the total provincial population as of the 2021 Canadian census.[1] In comparison with the province-wide statistics, as of the 2021 Canadian census, a small minority of the South Asian British Columbian community was third or more generation, numbering 18,030 people or 3.80% of the total South Asian British Columbian population.[1]

| Metropolitan area | First generation | Second generation | Third generation or more | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Vancouver CMA | 245,410 | 66.45% | 111,135 | 30.09% | 12,750 | 3.45% |

| Abbotsford–Mission CMA | 32,085 | 64.38% | 16,515 | 33.14% | 1,240 | 2.49% |

| Victoria CMA | 8,395 | 61.21% | 4,120 | 30.04% | 1,205 | 8.79% |

| Kelowna CMA | 4,950 | 66.71% | 2,055 | 27.7% | 420 | 5.66% |

| Kamloops CMA | 3,040 | 68.78% | 1,130 | 25.57% | 250 | 5.66% |

| Prince George CA | 2,755 | 70.55% | 930 | 23.82% | 215 | 5.51% |

| Chilliwack CMA | 1,835 | 56.03% | 1,170 | 35.73% | 270 | 8.24% |

| Nanaimo CMA | 2,195 | 69.13% | 775 | 24.41% | 210 | 6.61% |

| Squamish CA | 1,000 | 65.36% | 490 | 32.03% | 35 | 2.29% |

| Vernon CA | 805 | 61.69% | 370 | 28.35% | 135 | 10.34% |

| Penticton CA | 785 | 64.34% | 355 | 29.1% | 75 | 6.15% |

| Fort St. John CA | 940 | 83.93% | 165 | 14.73% | 20 | 1.79% |

| Duncan CA | 595 | 58.91% | 275 | 27.23% | 140 | 13.86% |

| Terrace CA | 525 | 72.92% | 145 | 20.14% | 55 | 7.64% |

| Prince Rupert CA | 525 | 79.55% | 125 | 18.94% | 10 | 1.52% |

| Courtenay CA | 440 | 70.4% | 125 | 20% | 65 | 10.4% |

| Campbell River CA | 380 | 70.37% | 135 | 25% | 25 | 4.63% |

| Port Alberni CA | 275 | 56.7% | 135 | 27.84% | 75 | 15.46% |

| Dawson Creek CA | 405 | 90% | 30 | 6.67% | 15 | 3.33% |

| Williams Lake CA | 360 | 80% | 70 | 15.56% | 20 | 4.44% |

| Cranbrook CA | 320 | 87.67% | 20 | 5.48% | 25 | 6.85% |

| Quesnel CA | 215 | 67.19% | 60 | 18.75% | 45 | 14.06% |

| Nelson CA | 175 | 63.64% | 65 | 23.64% | 30 | 10.91% |

| Trail CA | 225 | 83.33% | 25 | 9.26% | 20 | 7.41% |

| Parksville CA | 115 | 50% | 65 | 28.26% | 50 | 21.74% |

| Salmon Arm CA | 110 | 55% | 45 | 22.5% | 45 | 22.5% |

| Powell River CA | 110 | 70.97% | 20 | 12.9% | 25 | 16.13% |

| Ladysmith CA | 30 | 42.86% | 35 | 50% | 5 | 7.14% |

| British Columbia | 313,570 | 66.16% | 142,360 | 30.04% | 18,030 | 3.8% |

Geographical distribution

According to the 2021 census, regional districts in British Columbia with the highest proportions of South Asian Canadians included Fraser Valley (16.9%), Metro Vancouver (14.2%), Fraser−Fort George (4.3%), Okanagan−Similkameen (3.9%), Thompson−Nicola (3.6%), Squamish−Lillooet (3.5%), Capital (3.4%), Central Okanagan (3.4%), Peace River (2.6%), Kitimat−Stikine (2.4%), and Nanaimo (2.1%).[141]

| Regional district | Largest subdivision | 2021[141] | 2016 | 1986[142][143] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | ||

| Metro Vancouver | Vancouver | 369,290[144] | 14.17% | 291,005[145] | 11.99% | 49,870 | 3.99% |

| Fraser Valley | Abbotsford | 53,585[146] | 16.87% | 39,920[147] | 13.82% | — | — |

| Capital | Victoria | 13,825[148] | 3.4% | 10,850[149] | 2.91% | 3,375 | 1.3% |

| Central Okanagan | Kelowna | 7,425[150] | 3.4% | 3,955[151] | 2.08% | 470 | 0.53% |

| Thompson−Nicola | Kamloops | 4,940[152] | 3.55% | 3,110[153] | 2.41% | 2,610 | 2.72% |

| Fraser−Fort George | Prince George | 4,060[154] | 4.26% | 2,720[155] | 2.93% | 2,130 | 2.39% |

| Nanaimo | Nanaimo | 3,450[156] | 2.08% | 2,370[157] | 1.56% | 1,035 | 1.27% |

| Okanagan−Similkameen | Penticton | 3,445[158] | 3.93% | 2,950[159] | 3.67% | 595 | 1.02% |

| Squamish−Lillooet | Squamish | 1,725[160] | 3.48% | 1,550[161] | 3.73% | 685 | 3.85% |

| Peace River | Fort St. John | 1,600[162] | 2.65% | 990[163] | 1.61% | 400 | 0.7% |

| North Okanagan | Vernon | 1,390[164] | 1.55% | 940[165] | 1.14% | 435 | 0.8% |

| Cowichan Valley | Duncan | 1,295[166] | 1.48% | 1,375[167] | 1.68% | 1,380 | 2.65% |

| Kitimat−Stikine | Terrace | 895[168] | 2.4% | 625[169] | 1.69% | 1,220 | 3.1% |

| Cariboo | Williams Lake | 890[170] | 1.43% | 1,045[171] | 1.71% | 2,720 | 4.59% |

| East Kootenay | Cranbrook | 830 | 1.29% | 385 | 0.65% | 610 | 1.16% |

| Central Kootenay | Nelson | 730 | 1.19% | 475 | 0.81% | 95 | 0.2% |

| Comox Valley | Courtenay | 665 | 0.94% | 480 | 0.73% | — | — |

| North Coast | Prince Rupert | 665 | 3.7% | 420 | 2.35% | 600 | 2.61% |

| Columbia–Shuswap | Salmon Arm | 585 | 1.05% | 405 | 0.81% | 415 | 1.05% |

| Strathcona | Campbell River | 545 | 1.15% | 275 | 0.63% | — | — |

| Alberni−Clayoquot | Port Alberni | 530[172] | 1.62% | 640[173] | 2.12% | 1,270 | 4.2% |

| Bulkley–Nechako | Smithers | 460 | 1.23% | 255 | 0.68% | 820 | 2.2% |

| Sunshine Coast | Sechelt | 430 | 1.36% | 235 | 0.8% | 15 | 0.09% |

| Kootenay Boundary | Trail | 415 | 1.28% | 125 | 0.41% | 225 | 0.75% |

| qathet | Powell River | 160 | 0.76% | 70 | 0.36% | 125 | 0.69% |

| Mount Waddington | Port Hardy | 70 | 0.65% | 40 | 0.37% | 225 | 1.51% |

| Northern Rockies | Fort Nelson | 65 | 1.48% | 40 | 0.76% | — | — |

| Central Coast | Bella Coola | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Stikine | Atlin | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 35 | 1.73% |

| British Columbia | Total | 473,965 | 9.64% | 365,705 | 8.02% | 78,810 | 2.77% |

As per the 2021 census, metropolitan areas in British Columbia with large South Asian Canadian communities include Vancouver (369,295), Abbotsford-Mission (49,835), Victoria (13,715), Kelowna (7,420), Kamloops (4,420), Prince George (3,905), Chilliwack (3,275), Nanaimo (3,175), Squamish (1,530), and Vernon (1,305). Additionally, according to the 2021 census, metropolitan areas in British Columbia with the highest proportions of South Asian Canadians include Abbotsford-Mission (25.9%), Vancouver (14.2%), Squamish (6.4%), Prince Rupert (5.0%), Prince George (4.4%), Kamloops (4.0%), Fort St. John (3.9%), Terrace (3.7%), Victoria (3.5%), and Kelowna (3.4%).

| Metro area | 2021[174] | 2016[175] | 1986[176][177][178][179] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Vancouver CMA | 369,295 | 14.17% | 291,005 | 11.99% | 51,975 | 3.81% |

| Abbotsford–Mission CMA | 49,835 | 25.94% | 38,250 | 21.69% | 4,775 | 5.51% |

| Victoria CMA | 13,715 | 3.53% | 10,780 | 3.01% | 3,375 | 1.35% |

| Kelowna CMA | 7,420 | 3.4% | 3,955 | 2.08% | 470 | 0.53% |

| Kamloops CMA | 4,420 | 4% | 2,650 | 2.63% | 1,510 | 2.47% |

| Prince George CA | 3,905 | 4.44% | 2,630 | 3.09% | 1,810 | 2.69% |

| Chilliwack CMA | 3,275 | 2.94% | 1,465 | 1.48% | 320 | 0.65% |

| Nanaimo CMA | 3,175 | 2.82% | 2,115 | 2.07% | 995 | 1.66% |

| Squamish CA | 1,530 | 6.39% | 1,320 | 6.77% | — | — |

| Vernon CA | 1,305 | 2% | 880 | 1.47% | 380 | 0.9% |

| Penticton CA | 1,220 | 2.64% | 965 | 2.29% | 345 | 0.9% |

| Fort St. John CA | 1,120 | 3.94% | 635 | 2.27% | 135 | 1.02% |

| Duncan CA | 1,010 | 2.18% | 1,040 | 2.41% | 1,020 | 4.29% |

| Terrace CA | 720 | 3.69% | 410 | 2.65% | 500 | 2.89% |

| Prince Rupert CA | 660 | 4.96% | 410 | 3.28% | 560 | 3.23% |

| Courtenay CA | 625 | 1.01% | 455 | 0.86% | 15 | 0.04% |

| Campbell River CA | 540 | 1.35% | 255 | 0.69% | 375 | 1.41% |

| Port Alberni CA | 485 | 1.91% | 600 | 2.43% | 1,215 | 4.67% |

| Dawson Creek CA | 450 | 2.59% | 340 | 2.89% | 70 | 0.67% |

| Williams Lake CA | 450 | 1.93% | 425 | 2.38% | 1,415 | 4.24% |

| Cranbrook CA | 365 | 1.39% | 185 | 0.72% | 115 | 0.73% |

| Quesnel CA | 320 | 1.4% | 535 | 2.33% | 1,275 | 5.5% |

| Nelson CA | 275 | 1.47% | 135 | 0.75% | — | — |

| Trail CA | 270 | 1.95% | — | — | 135 | 0.67% |

| Parksville CA | 230 | 0.77% | 215 | 0.77% | — | — |

| Salmon Arm CA | 200 | 1.06% | 155 | 0.9% | — | — |

| Powell River CA | 155 | 0.89% | 65 | 0.4% | 95 | 0.52% |

| Ladysmith CA | 70 | 0.46% | — | — | — | — |

| Kitimat CA | — | — | — | — | 720 | 6.47% |

| British Columbia | 473,965 | 9.64% | 365,705 | 8.02% | 78,810 | 2.77% |

South Coast

Metro Vancouver

The Vancouver Metropolitan Area, including Surrey, has a high concentration of South Asian Canadians.[180]

According to the 2021 census, the South Asian Canadian population in the Metro Vancouver Regional District is 369,295 persons or 14.2 percent of the region's total population; an increase over the 2016 census count of 291,005 persons or 12 percent of the total population.[181] As per the Statistics Canada 2001 census, the South Asian Canadian population in the region stood at approximately 163,340 persons.[93]

The 2006 census counted 33,415 South Asian Canadians in the City of Vancouver.[182] In the same census report, the South Asian Canadian population in the City of Surrey was considerably higher, at approximately had 107,810 persons.[183]

| Subdivision | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[184] | 2016[185] | 1986[142][143] | |

| Surrey | 37.81% | 32.85%[186] | 5.03% |

| Delta | 26.09% | 20.31%[187] | 4.2% |

| New Westminster | 10.38% | 8.28%[188] | 4.34% |

| Burnaby | 9.42% | 8.2%[189] | 4.33% |

| White Rock | 7.6% | 5.2% | 0.14% |

| Richmond | 7.38% | 7.36%[190] | 6.43% |

| Langley (city) | 6.99% | 2.33% | 0.43% |

| Vancouver (city) | 6.9% | 6.09%[191] | 4.1% |

| Langley (district) | 6.66% | 4.44% | 1.36% |

| Metro Vancouver Subdivision A | 5.83% | 4.24% | 1.65% |

| Port Coquitlam | 5.78% | 4.84% | 2.72% |

| Pitt Meadows | 5.36% | 4.77% | 2.94% |

| Coquitlam | 5.02% | 4.5%[192] | 2.72% |

| Maple Ridge | 4.72% | 3.08% | 0.81% |

| North Vancouver (city) | 3.65% | 3.92% | 2.05% |

| West Vancouver | 3.24% | 2.59% | 0.91% |

| North Vancouver (district) | 3.18% | 3.94% | 2.04% |

| Port Moody | 3% | 2.39% | 1.24% |

| Anmore | 2.92% | 1.81% | — |

| Lions Bay | 1.44% | 1.09% | 0% |

| Bowen Island | 0.59% | 1.91% | — |

| Belcarra | 0% | 1.68% | 0% |

Fraser Valley

According to the 2021 census, the South Asian Canadian population in the Fraser Valley Regional District is 53,585 persons or 16.9 percent of the region's total population; an increase over the 2016 census count of 39,920 persons or 13.8 percent of the total population.[193]

The Abbotsford metropolitan area, in the Fraser Valley Regional District, has Canada's highest proportion of Indo-Canadians.[194] In 2006 Abbotsford City had 23,355 South Asian visible minorities, and 23,615 persons indicated they had South Asian ethnic ancestry.[195] As of November 2009 Punjabi Sikhs were the majority group within the Indo-Canadian population in Abbotsford, and the city also had small numbers of Indo-Canadian Hindus, Ismailis, other Muslims, and Christians. 96% of the Indo-Canadians in Abbotsford were Punjabi at that time, and Punjabis originated from Doaba, Majha, Malwa, and other regions.[196] As of 2006 to 2009, the Punjabi language was spoken by 39.3% of Abbotsford households, making it the second most-commonly spoken language at home after English.[197]

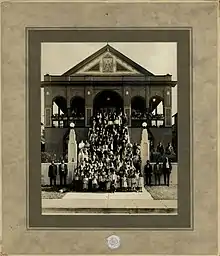

Indo-Canadian settlement of Abbotsford began in 1905, and the existing residents of the community initially had a positive reception to the Indo-Canadians. The MSA Museum Society stated that only a few of the existing residents had anti-Indo-Canadian feelings and that "most of the community" had "not only tolerated but welcomed" the Indo-Canadians.[198] Around 1911 the largest employer of Abbotsford Sikh people was the Tretheway family, the owner of the Abbotsford Lumber Company. The Hartnell Lumber Mill, which provided residential quarters, also employed large numbers of Indo-Canadians.[198] In addition Indo-Canadians in Abbotsford worked in berry farms and in area businesses.[199] The first permanent gurdwara and Canada's oldest still-standing gurdwara, the Gur Sikh Temple, was built in 1911 with lumber donated from the Trethewey family and opened on February 25, 1912. Prior to the construction of the gurdwara, Indo-Canadian Sikhs held services at a house in Maple Grove. The MSA Museum stated that according to the memory of Abbotsford resident Margaret Weir, the first Indo-Canadian baby in Abbotsford was born in 1912.[198] Additional members of the ethnic group first arrived in the 1920s.[199]

A 1982 survey of farm workers in British Columbia by the Abbotsford-Matsqui Community Services organization stated that many of the Punjabi farm workers in British Columbia were illiterate even in Punjabi. The survey had chronicled 270 Punjabi-speaking and French-speaking farm workers.[200]

As of 2006 persons of Indian origin were immigrating to Abbotsford, and therefore maintaining the city's Indo-Canadian presence. At the same time many members of Abbotsford's Indo-Canadian community were in their third and fourth generations.[201]

There were 6,075 residents of Abbotsford who had Indian origins in 1991.[198] In 2001 73% of Abbotsford's visible minorities were Indo-Canadian, and about 15% of the city's total population was Indo-Canadian. In 2006 72.5% of the city's visible minority population was Indo-Canadian. From 2001 to 2006 the Indo-Canadian population percentage rose by 7%, up to 18%. The percentage of immigrants coming from India to Abbotsford increased by 20% within a five year span ending around 2009.[197]

In 2014 Ken Harar of the Abbotsford News wrote that Mission "has always had a vibrant Indo-Canadian community".[202] This community was active since the early 1900s. An Indo-Canadian volleyball team, "Mission Sikhs", played in the area. In 1950, Naranjan Grewall became the first Indo-Canadian elected to public office when he took a position in Mission City's government as a Commissioner, and in 1954, was elected as the Chairman.[203] In 2006 2,220 South Asian visible minorities resided in Mission, making up 63.2% of the city's visible minorities, and 2,180 persons in Mission claimed South Asian ancestry, making up 3.8% of the total persons in the city.[204]

| Subdivision | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[184] | 2016[185] | 1986[142][143] | |

| Abbotsford | 30.18% | 25.48% | 4.64%[lower-alpha 11] |

| Fraser Valley Subdivision G | 12.13% | 6.21% | — |

| Mission | 10.66% | 7.84% | 5.41% |

| Fraser Valley Subdivision F | 7.25% | 3.89% | — |

| Fraser Valley Subdivision A | 4.26% | 0% | — |

| Chilliwack | 3.29% | 1.61% | 0.7% |

| Fraser Valley Subdivision B | 3.21% | 0% | — |

| Fraser Valley Subdivision D | 2.26% | 0% | — |

| Harrison Hot Springs | 2.15% | 1.39% | 0% |

| Hope | 1.58% | 2.56% | 3.48% |

| Kent | 1.43% | 0.86% | 0.31% |

| Fraser Valley Subdivision C | 0.9% | 0% | — |

| Fraser Valley Subdivision H | 0.41% | 2.2% | — |

| Fraser Valley Subdivision E | 0% | 1.76% | — |

| Matsqui | — | — | 5.97% |

| Fraser Cheam Subdivision A | — | — | 5.03% |

| Dewdney-Alouette Subdivision A | — | — | 2.12% |

| Central Fraser Valley Subdivision A | — | — | 0% |

| Fraser Cheam Subdivision B | — | — | 0% |

| Fraser Cheam Subdivision C | — | — | 0% |

Vancouver Island

Victoria, within the Capital Regional District, had 1,015 South Asian visible minorities in 2006. 1,105 persons stated that they had South Asian origins.[205] Officials of the India-Canada Cultural Association of Victoria (ICCA) stated in 2013 that the Victoria area had about 5,000 families with Indian descent.[206]

Outside of Victoria, smaller South Asian communities exist all along the Island's east coast. Sikh temples exist in Campbell River, Port Alberni, Nanaimo, Lake Cowichan, Duncan, and most notably in the historic settlement of Paldi. Mayo Singh founded the town of Paldi on Vancouver Island, naming it after Paldi, Hoshiarpur, Punjab, and accordingly this town hosted a large Indo-Canadian community for several decades.[207] Until the 1970s, Paldi was the only Sikh majority area in all of Canada.[128]

As Indo-Canadians in early Vancouver Island were extremely influential, owning large companies and land holdings – a number of public spaces on the Island are named for Indo-Canadians. Kapoor Regional Park for example, is named after businessman and philanthropist Kapoor Singh Siddoo.[208] A park near Shawnigan Lake is named Drs. Jagdis K and Sarjit K. Siddoo Park after other members of the Siddoo family who donated the land.[209] Streets in Paldi bare Punjabi first names such as "Rajeet Road", "Kapoor Road", "Bishan Road", and "Jindo Road". Similarly a street in Lake Cowichan is named "Natara Place", after Sikh priest Natara Singh who lived in the area.[210] The same town also has a "Johel Street" and "Johel Court", the surname of another prominent Punjabi family in the area.

| Subdivision | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[184] | 2016[185] | 1986[142][143] | |

| View Royal | 5.82% | 5.7% | — |

| Saanich | 5.72% | 5.18% | 2.63% |

| Langford | 4.07% | 2.68% | — |

| Nanaimo | 3.19% | 2.28% | 2.04% |

| Victoria | 2.89% | 2.38% | 1.21% |

| North Cowichan | 2.86% | 3.08% | 4.88% |

| Central Saanich | 2.85% | 2.43% | 0.88% |

| Port Alberni | 2.59% | 3% | 6.46% |

| North Saanich | 2.26% | 1.34% | 0.21% |

| Oak Bay | 2.1% | 1.77% | 0.09% |

| Esquimalt | 1.76% | 1.33% | 0.92% |

| Lake Cowichan | 1.66% | 2.48% | 7.32% |

| Courtenay | 1.6% | 1.3% | 0.05% |

| Campbell River | 1.53% | 0.77% | 2.28% |

| Colwood | 1.49% | 1.23% | 0.83% |

| Mount Waddington Subdivision A | 1.38% | 0% | 0% |

| Ucluelet | 1.26% | 0% | 0.32% |

| Sidney | 1.19% | 0.85% | 0.06% |

| Port Hardy | 1.04% | 0.61% | 3.34% |

| Duncan | 0.97% | 1.68% | 2.71% |

| Tofino | 0.9% | 1.71% | 0.56% |

| Nanaimo Subdivision A | 0.88% | 0.36% | 0.41% |

| Port McNeil | 0.85% | 0.43% | 1.4% |

| Cowichan Valley Subdivision C | 0.79% | 1.29% | 0.35% |

| Metchosin | 0.74% | 0.44% | 0.14% |

| Comox | 0.73% | 0.51% | 0.07% |

| Cowichan Valley Subdivision A | 0.72% | 0.98% | 2.81% |

| Ladysmith | 0.68% | 0.48% | 2.28% |

| Cowichan Valley Subdivision B | 0.62% | 0.83% | 0% |

| Parksville | 0.6% | 0.79% | 0% |

| Alberni-Clayoquot Subdivision E | 0.68% | 0.91% | — |

| Comox Valley Subdivision A | 0.64% | 0.49% | — |

| Qualicum Beach | 0.57% | 0.41% | 0% |

| Cumberland | 0.46% | 0% | 0% |

| Comox Valley Subdivision C | 0.39% | 0.29% | — |

| Strathcona Subdivision C | 0.37% | 0% | — |

| Comox Valley Subdivision B | 0.2% | 0.42% | — |

| Alberni-Clayoquot Subdivision F | 0% | 2.61% | — |

| Lantzville | 0% | 2.5% | — |

| Alberni-Clayoquot Subdivision B | 0% | 2.35% | 0% |

| Alberni-Clayoquot Subdivision C | 0% | 1.61% | — |

| Strathcona Subdivision B | 0% | 1.4% | — |

| Strathcona Subdivision A | 0% | 1.35% | — |

| Alberni-Clayoquot Subdivision D | 0% | 0.62% | — |

| Strathcona Subdivision D | 0% | 0.23% | — |

| Tahsis | 0% | 0% | 12.54% |

| Gold River | 0% | 0% | 1.8% |

| Alberni-Clayoquot Subdivision A | 0% | 0% | 1.2% |

| Port Alice | 0% | 0% | 0.75% |

| Capital Subdivision B | — | — | 0.67% |

| Comox-Strathcona Subdivision B | — | — | 0.44% |

| Capital Subdivision A | — | — | 0.06% |

| Comox-Strathcona Subdivision C | — | — | 0.03% |

| Alert Bay | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Mount Waddington Subdivision C | 0% | 0% | — |

| Mount Waddington Subdivision D | 0% | 0% | — |

| Nanaimo Subdivision B | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Sayward | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Zeballos | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Capital Subdivision C | — | — | 0% |

| Comox-Strathcona Subdivision A | — | — | 0% |

| Comox-Strathcona Subdivision D | — | — | 0% |

| Mount Waddington Subdivision B | — | — | 0% |

Sunshine Coast/Sea-to-Sky Corridor

Squamish in the Squamish-Lillooet Regional District has an Indo-Canadian population.[211] In 2006 it had 1,675 persons of South Asian origin and 1,695 persons claiming South Asian ancestry.[212]

| Subdivision | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[184] | 2016[185] | 1986[142][143] | |

| Squamish | 6.5% | 6.88% | 5.58% |

| Gibsons | 2.4% | 0.79% | 0.38% |

| Sechelt | 2.36% | 1.15% | 0% |

| Squamish-Lillooet Subdivision D | 1.95% | 0% | — |

| Lillooet | 1.1% | 0.89% | 5.95% |

| Powell River | 1.1% | 0.47% | 0.93% |

| Pemberton | 1.03% | 1.17% | 1.37% |

| Sunshine Coast Subdivision D | 0.85% | 1.02% | — |

| Whistler | 0.78% | 1.51% | 0.5% |

| Sunshine Coast Subdivision F | 0.65% | 2.51% | — |

| Sunshine Coast Subdivision E | 0.52% | 0.41% | — |

| Sunshine Coast Subdivision B | 0.34% | 0.37% | — |

| Squamish-Lillooet Subdivision C | 0% | 1.52% | — |

| Squamish-Lillooet Subdivision A | 0% | 0% | 0.27% |

| Sunshine Coast Subdivision A | 0% | 0% | 0.04% |

| Squamish-Lillooet Subdivision B | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Powell River Subdivision D | — | 0.95% | — |

| Powell River Subdivision B | — | 0.68% | — |

| Powell River Subdivision A | — | 0% | 0% |

| Powell River Subdivision C | — | 0% | — |

Southern Interior

Okanagan & Similkameen

There has been an Indo-Canadian population in the Okanagan region, including Kelowna.[213] The Okanagan Sikh community began at the turn of the 20th century and increased in size in the 1960s and 1970s. As of 1984 the Okanagan region had about 600 Sikh families.[78] In 2006 Kelowna had 1,870 South Asian visible minority residents. That year, 1,985 persons indicated that they had South Asian ethnic origins.[214] Indo-Canadian Sikhs in the Okanagan area had worked in the lumber industry.[213]

As of the 1980s most of the population had originated from rural India, and almost all Okanagan male Sikhs had job experience in the area sawmills. As of the 1980s some Okanagan Sikhs had interacted with urban India prior to moving to Canada.[91] Annamma Joy, in the 1975 PhD thesis Accommodation and Cultural Persistence: The Case of the Sikhs and Portuguese in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia, a study of the Sikh population of the Okanagan, surveyed 40 Sikhs and concluded that most Sikhs in the Okanagan originated from rural areas in Jullunder and Hoshiarpur; those who had attained university education had done so in other Punjabi towns.[215]

Sikh Indo-Canadian women worked as fruit pickers on farms and in the domestic sector, including kitchen workers and maids. As of the 1980s, within the Okanagan Valley male Sikh persons were more likely to have a command of English than female Sikhs, and 85% of the males stated that they were not comfortable using the English language.[91]

| Subdivision | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[184] | 2016[185] | 1986[142][143] | |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision A | 15.83% | 15.86% | 0% |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision C | 14.47% | 16% | 0% |

| Cawston | 12.73% | 11.73% | — |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision B | 11.38% | 10.73% | 1.56% |

| Oliver | 9.38% | 8.86% | 2.14% |

| Osoyoos | 5.78% | 4.63% | 0.69% |

| Kelowna | 4.44% | 2.61% | 0.67% |

| Penticton | 3.18% | 2.83% | 1.53% |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision G | 3.05% | 6.28% | — |

| North Okanagan Subdivision B | 2.98% | 1.26% | 0.34% |

| Central Okanagan Subdivision A | 2.47% | 2.76% | 0.48% |

| Vernon | 2.41% | 1.88% | 1.73% |

| Princeton | 2.32% | 0.54% | 0.35% |

| Summerland | 2.01% | 1.53% | 0.33% |

| Keremeos | 1.72% | 4.5% | 0.61% |

| West Kelowna | 1.65% | 1.17% | — |

| Coldstream | 1.14% | 1.05% | 0.67% |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision D | 1.01% | 0.69% | — |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision E | 1% | 2.12% | — |

| North Okanagan Subdivision C | 0.89% | 0.26% | — |

| Armstrong | 0.88% | 1.02% | 0% |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision F | 0.72% | 0.5% | — |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision I | 0.66% | — | — |

| Central Okanagan Subdivision B | 0.52% | — | 0.78% |

| Peachland | 0.52% | 0.83% | 0% |

| North Okanagan Subdivision D | 0.52% | 0.76% | — |

| Enderby | 0.5% | 0% | 0% |

| Okanagan-Similkameen Subdivision H | 0.46% | 0% | — |

| Spallumcheen | 0% | 0.2% | 0% |

| Lumby | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| North Okanagan Subdivision E | 0% | 0% | — |

| North Okanagan Subdivision F | 0% | 0% | — |

| North Okanagan Subdivision A | — | — | 0% |

Thompson-Nicola/Columbia-Shuswap

Kamloops in the Thompson-Nicola Regional District had 1,545 South Asian visible minorities in 2006. That year, 1,595 persons claimed South Asian origins.[216]

Merritt in the Nicola Valley has an Indo-Canadian population.[211] In 2006 it had 615 South Asian visible minorities and 545 persons claiming South Asian ethnic ancestry.[217]

| Subdivision | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[184] | 2016[185] | 1986[142][143] | |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision B | 20% | 0% | 0.15% |

| Merritt | 5.56% | 6.03% | 13.19% |

| Golden | 4.62% | 3.48% | 9.8% |

| Kamloops | 4.51% | 2.96% | 2.47% |

| Revelstoke | 1.65% | 1.01% | 0.24% |

| Salmon Arm | 1.1% | 0.91% | 0.09% |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision A | 0.65% | 0% | 3.81% |

| Ashcroft | 0.62% | 0% | 0% |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision M | 0.61% | 0.95% | — |

| Columbia-Shuswap Subdivision D | 0.34% | 0.25% | — |

| Columbia-Shuswap Subdivision C | 0.28% | 0% | 0.04% |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision P | 0.25% | 0% | — |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision J | 0% | 2.55% | — |

| Columbia-Shuswap Subdivision F | 0% | 0.82% | — |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision O | 0% | 0.76% | — |

| Logan Lake | 0% | 0.5% | 1.89% |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision L | 0% | 0.34% | — |

| Columbia-Shuswap Subdivision A | 0% | 0% | 1.79% |

| Lytton | 0% | 0% | 1.47% |

| Columbia-Shuswap Subdivision B | 0% | 0% | 0.68% |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision E | 0% | 0% | 0.2% |

| Cache Creek | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Chase | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Clinton | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Columbia-Shuswap Subdivision E | 0% | 0% | — |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision I | 0% | 0% | — |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision N | 0% | 0% | — |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision D | — | — | 1.25% |

| Thompson-Nicola Subdivision C | — | — | 0% |

Kootenays

| Subdivision | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021[184] | 2016[185] | 1986[142][143] | |

| Trail | 3.36% | 0.61% | 0.99% |

| Castlegar | 3.35% | 2.76% | 0.56% |

| East Kootenay Subdivision F | 3.35% | 0% | — |

| Nelson | 2.33% | 0.93% | 0.06% |

| Grand Forks | 2.19% | 1.18% | 0.94% |

| Fernie | 1.86% | 0.58% | 1.95% |

| Cranbrook | 1.84% | 0.92% | 0.6% |

| Creston | 1.49% | 0.49% | 0.13% |

| Rossland | 0.97% | 0.4% | 0.29% |

| Elkford | 0.91% | 1% | 7.22% |

| Salmo | 0.88% | 0% | 0% |

| Warfield | 0.86% | 0% | 0% |

| Sparwood | 0.84% | 2.11% | 3.41% |

| Invermere | 0.79% | 0.78% | 0% |

| Central Kootenay Subdivision B | 0.63% | 0.65% | 0.08% |

| Kimberley | 0.57% | 0.55% | 0% |

| Central Kootenay Subdivision E | 0.52% | 0.4% | — |

| Central Kootenay Subdivision H | 0.4% | 0.98% | — |

| Central Kootenay Subdivision I | 0.38% | 0.79% | — |

| Kootenay Boundary Subdivision E | 0.35% | 0% | — |

| Kootenay Boundary Subdivision D | 0.31% | 0.31% | — |

| Central Kootenay Subdivision F | 0.24% | 0.88% | — |

| Silverton | 0% | 6.25% | 0% |

| East Kootenay Subdivision E | 0% | 1.43% | — |

| Central Kootenay Subdivision C | 0% | 0.68% | 0.15% |

| Central Kootenay Subdivision J | 0% | 0.64% | — |

| Central Kootenay Subdivision G | 0% | 0.62% | — |

| Kootenay Boundary Subdivision A | 0% | 0.53% | 0.26% |

| East Kootenay Subdivision C | 0% | 0.17% | 0% |

| Midway | 0% | 0% | 7.94% |

| Montrose | 0% | 0% | 5.56% |

| East Kootenay Subdivision A | 0% | 0% | 1.29% |

| Central Kootenay Subdivision A | 0% | 0% | 0.71% |

| Greenwood | 0% | 0% | 0.61% |

| Fruitvale | 0% | 0% | 0.25% |

| Kootenay Boundary Subdivision B | 0% | 0% | 0.19% |

| East Kootenay Subdivision B | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Kaslo | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Nakusp | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| New Denver | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Slocan | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Central Kootenay Subdivision D | 0% | 0% | — |

| Central Kootenay Subdivision K | 0% | 0% | — |

| East Kootenay Subdivision G | 0% | 0% | — |

| Kootenay Boundary Subdivision C | 0% | 0% | — |

Central Interior & North

As of 1997 the largest immigrant group arriving in Prince George, in the Fraser-Fort George Regional District, are the Indo-Canadians.[218] In 2006, within Prince George, 1,785 persons were South Asian visible minorities and 1,880 persons claimed South Asian ethnic ancestry.[219] In 1997, 11.7% of the immigrants in Prince George were Indo-Canadians who had arrived in the years 1986–1991.[218]

In the 1990s, Fort St. James had the highest proportion of South Asians of any municipality in Canada – at approximately 20%. The South Asian community of Fort St. James consisted mostly of Punjabis of the Sikh faith. The local Sikh temple was put for sale in 2012, as fewer than 50 South Asian residents remain in the community.[220]

Quesnel in the Cariboo Regional District has an Indo-Canadian population.[211] In 2006 it had 550 South Asian visible minorities and 575 persons claiming South Asian origins.[221]

Prince Rupert, within the Skeena-Queen Charlotte Regional District, had 535 South Asian visible minorities in 2006. That year, there were 550 people claiming South Asian origins in Prince Rupert.[222] According to an account, the Prince Rupert Indo-Canadian community had about 30–40 adult males and about four extended families in the early 1970s.[112] Initially Prince Rupert did not have its own gurdwara.[123] The Indo-Canadian Association, established in 1972, bought a gurdwara facility for $38,000. The association, on June 16, 1974, was renamed the Indo-Canadian Sikh Association.[112] Nayar wrote that the Indo-Canadian population of Skeena Country prioritize economic success and employment, education, and English proficiency "in contrast to Punjabis in large urban centres" and that "Punjabis from the Skeena region generally dislike" the "Punjabi Bubble" that involves few interactions with non-Punjabis, awareness of intra-Punjab geography, and physical segregation from non-Punjabis.[223] The Skeena Punjabis interact with both White Canadians and First Nations.[224]

Commerce

The initial Sikh Indo-Canadian population primarily worked in laborer trades, with about 75% of the total population working in the forestry industry as of 1967. Indo-Canadians worked in Okanagan Valley fruit farms and Fraser Valley dairy farms. Some Indo-Canadians also established retail operations and commercial fishing operations.[91]

Seasonal outdoor jobs such as field-hand work, road work, railway gang work, fruit picking, and clearing lots had a slightly higher pay compared to indoor work, and the focus was on making higher wages instead of stable and long term employment, so many of the very first Punjabis to come to British Columbia took these jobs. They transitioned into sawmill work because it had better pay.[18] Many Indo-Canadians in the pre-1947 era had few choices for jobs, because South Asians until that year were unable to get the right of franchise,[70] or the right to vote in British Columbian provincial elections. Several jobs required having that right and therefore persons of Indian descent were not eligible to apply for them. Therefore jobs in the education and legal sectors were not available.[50] In addition many private sector, municipal, and public service jobs were also barred from being held by East Indian persons.[70] Government contract work was unavailable for those of Indian descent.[50]

Sawmill industry

.jpg.webp)

In British Columbia the agricultural and forestry sectors have significant numbers of Indo-Canadians.[17] Since the beginning of immigration from South Asia, Indo-Canadians in British Columbia, have been involved in the wood-related sectors.[128] Punjabis were the majority ethnic group ethnic group within the sawmill workforce by 1907, as many Anglo Canadians had disinterest in being sawmill workers. Nayar wrote that "In effect, the Punjabi male immigrant living in British Columbia became equated with manual sawmill labour."[18] The Punjabis were associated with sawmill work even though there were also East Asians in the sawmills.[18] Some Punjabi sawmills and farms were leased by collective shares.[225] Punjabi-owned sawmills became a places where Punjabis could get skilled labour, or alternatively, find employment.[226] By 1923 Indo-Canadian-owned sawmills included the Bharat Lumber Company in Vancouver, the Virginia Lumber Company in Coombs, the Mayo Lumber Company and Tansor Lumber Company in Duncan, and the Eastern Lumber Company in Ladysmith.[227] By that year Indo-Canadians also worked in sawmills in Vancouver, Fraser Mills, New Westminster, and Victoria that were owned by non-Indo-Canadians.[228]

1960s through the modern era

In the 1960s Punjabis continued to be a part of the sawmill business.[18] As of 1973, very few Sikh women worked, so most of the employed were men. Most women who worked did so at government agencies since there was a belief private businesses would discriminate against them: the jobs women often held were clerical and office positions. Many men worked at logging camps and sawmills.[128]

As of circa 1987 about 9,600 farm workers in the Fraser Valley/Lower Mainland region were immigrants of Punjabi origin, making up 80% of that region's farm workers.[229] By the 1970s these farm workers operated under a contracting system which involved the contractors transporting their charges and taking cuts from their charges' paychecks.[230] Illegal and legal immigrants often had little English fluency and knowledge of Canadian employment customs,[231] and some of them were also illiterate.[232] The contractors themselves were also Punjabi East Indians. The nature of piece-rate work system, which pays by product instead of using a salary, made these workers dependent on contractors,[231] since they required the advance loans the contractors offer them, and they became dependent on these loans.[233]

East Indian farm workers often discussed their issues with family and friends and at meetings at gurdwaras, and this was a factor in establishing farm worker rights associations.[234]

Canada's first Indo-Canadian owned travel agency was Bains International Travel Service, established in Victoria by Kuldeep Singh Bains. Members of Bains's family established branch businesses in British Columbia. The original company closed around 2002, shortly after receiving an award for being open for 50 years.[235]

Politics