The pith helmet, also known as the safari helmet, salacot,[lower-alpha 1] sola topee, sun helmet, topee, and topi[lower-alpha 2] is a lightweight cloth-covered helmet made of sholapith.[1] The pith helmet originates from the Spanish military adaptation of the native salakot headgear of the Philippines.[2][3]

It was often worn by European travellers and explorers in the varying climates found in Southeast Asia, Africa, and the tropics, but it was also used in many other contexts. It was routinely issued to European military personnel serving overseas in hot climates from the mid-nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century.

Definition

Typically, a pith helmet derives from either the sola plant, Aeschynomene aspera, an Indian swamp plant, or from Aeschynomene paludosa.[4] In the narrow definition, a pith helmet is technically a type of sun helmet made out of pith material.[5] However, the pith helmet may more broadly refer to the particular style of helmet.[5] In this case, a pith helmet can be made out of cork, fibrous, or similar material.[5] It was designed to shade the wearer's head and face from the sun.[6]

History

Origin

The origin of the pith helmet is the traditional Filipino headgear known as the salakot (Spanish salacot, a term still also used for pith helmets).[7][8] They are usually dome-shaped or cone-shaped and can range in size from having very wide brims to being almost helmet-like. The tip of the crown commonly has a spiked or knobbed finial made of metal or wood. It is held in place by an inner headband and a chin strap. These were originally made from various lightweight materials like woven bamboo, rattan, and bottle gourd; sometimes inlaid with precious metals, coated with water-proof resin, or covered in cloth.[9][10][3][11]

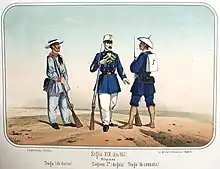

Salacots were used by native Filipino auxiliaries in the Spanish colonial military as protection against the sun and rain during campaigns. They were adopted fully by both native and Spanish troops in the Philippines by the early 18th century. The military versions were commonly cloth-covered and gradually took on the shape of the Spanish cabasset or morion.[12][9][2][3]

19th century

The salacot design was later adopted by the French colonial troops in Indochina in the 19th century (who called it the salacco or salacot, a term also later applied to the native Vietnamese cone-shaped or disk-like nón lá) due to its effectiveness in protecting from damp and humid weather.[10] French marines also introduced the early version of the salacot to the French Antilles, where it became the salako, a cloth-covered headgear still mostly identical to the Filipino salakot in shape.[13] British and Dutch troops, and other colonial powers in nearby regions followed suit and the salacot became a common headgear for colonial forces in the mid-19th century.[9][10]

While this form of headgear was particularly associated with the British Empire, all European colonial powers used versions of it during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The French tropical helmet was first authorised for colonial troops in 1878.[14] The Dutch wore the helmet during the entire Aceh War (1873–1904), and the United States Army adopted it during the 1880s for use by soldiers serving in the intensely sunny climate of the Southwest United States.[15] It was also worn by the North-West Mounted Police in policing North-West Canada, 1873 through 1874 to the North-West Rebellion and even before the stetson in the Yukon Gold Rush of 1898.

European officers commanding locally recruited indigenous troops, as well as civilian officials in African and Asian colonial territories, used the pith helmet. Troops serving in the tropics usually wore pith helmets. However, on active service, they sometimes used alternatives such as the wide-brimmed slouch hat worn by US troops in the Philippines and by British Empire forces in the later stages of the Boer War.

Within the British Empire

The salacot was most widely adopted by the British Empire in British India, who originally called them "planters' hats". They began experimenting with derivative designs for a lightweight hat for troops serving in tropical regions. This led to a succession of designs, ultimately resulting in the "Colonial pattern" pith helmet and later designs like the Wolseley pattern.[9][16]

.jpg.webp)

Originally made of pith with small peaks or "bills" at the front and back, the British version of the helmet was covered by white cloth, often with a cloth band (or puggaree) around it, and small holes for ventilation. Military versions often had metal insignia on the front and could be decorated with a brass spike or ball-shaped finial. Depending on the occasion, the chinstrap would be either leather or brass chain. The base material later became the more durable cork, although still covered with cloth and frequently referred to as a "pith" helmet.

During the Anglo-Zulu War, British troops dyed their white pith helmets with tea, mud, or other makeshift means of camouflage.[17] Subsequently, khaki-coloured pith helmets became standard issue for active tropical service.

Colonial pattern

Sun helmets made of pith first appeared in India during the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars of the 1840s. Adopted more widely during the Indian Mutiny of 1857–59, they were generally worn by British troops serving in the Ashanti War of 1873, the Zulu War of 1878–79, and subsequent campaigns in India, Burma, Egypt, and South Africa.[18] This distinctively shaped early headwear became known as the Colonial pattern helmet.

The British Colonial pattern pith helmet, in turn, influenced the designs of other European pith helmets, including the Spanish and Filipino designs, by the latter half of the 19th century and the early 20th century.[9]

Wolseley pattern

.jpg.webp)

The Wolseley pattern helmet is a distinctive British design developed and popularised in the late 19th and early 20th century. It was the official designation for the universal sun helmet worn by the British Army from 1899 to 1948 and described in the 1900 Dress Regulations as "the Wolseley pattern cork helmet". It is named after Garnet Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley.[19] With its swept-back brim, it provided greater protection from the sun than the old Colonial pattern helmet. Its use was soon widespread among British personnel serving overseas and some Canadian units.[20] It continues to be used by the Royal Marines, both in full dress as worn by the Royal Marines Band Service and in number 1 dress ("blues") on certain ceremonial occasions.

Home Service helmet

At the same time, a similar helmet (of dark-blue cloth over the cork and incorporating a bronze spike) had been proposed for use in non-tropical areas. The British Army formally adopted this headgear, which they called the Home Service helmet, in 1878 (leading to the retirement of the shako). Most British line infantry (except fusilier and Scottish regiments) wore the helmet until 1902, when the khaki Service Dress was introduced. It was also worn by engineers, artillery (with a ball rather than a spike), and various administrative and other corps (again with a ball rather than a spike). The cloth of the helmet was generally dark blue, but a green version was worn by light infantry regiments and grey by several volunteer units. With the general adoption of khaki for field dress in 1903, the helmet became purely a full dress item, being worn as such until 1914.[21]

.jpg.webp)

It returned to use by regimental bands and officers attending levees in the inter-war period and is worn by regimental bands of British Army line infantry regiments to the present day.

The design of the Home Service helmet closely resembles the traditional custodian helmet worn since 1869 by several police forces in England and Wales. Black helmets of a similar shape were also part of the uniform of the Victoria Police during the late 19th century. The US Army also wore blue cloth helmets of the same pattern as the British model from 1881 to 1901 as part of their full-dress uniform. The version worn by cavalry and mounted artillery included plumes and cords in their respective service branches' colours (yellow or red).

20th century

Military use

Before the First World War, the Royal Navy and other navies had sometimes provided pith helmets for landing parties in tropical regions. Pith helmets were widely worn during the First World War by British, Belgian, French, Austrian-Hungarian, and German troops fighting in the Middle East and Africa. A white tropical helmet was issued to personnel of the French Navy serving in the Red Sea, Far Eastern waters, and the Pacific between 1922 and the 1940s.[22]

During the 1930s, the locally recruited forces maintained in the Philippines (consisting of the army and a gendarmerie) used sun helmets mostly made out of compressed coconut fiber called "Guinit". The Axis Second Philippine Republic's military, known as the Bureau of Constabulary, and guerrilla groups in the Philippines also wore this headdress.

Before the Second World War, Royal Navy officers wore the Wolseley helmet when in white (tropical) uniform; the helmet was plain white, with a narrow navy-blue edging to the top of the puggaree. Pith-styled helmets were used as late as the Second World War by Japanese, European and American military personnel in hot climates. Included in this category are the sun helmets worn in Ethiopia and North Africa by Italian troops, the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army, Union Defence Force, and Nazi Germany's Afrika Korps, as well as similar helmets used to a more limited extent by U.S. and Japanese forces in the Pacific Theater.[23]

.jpg.webp)

In the British Army, a khaki version was frequently worn, ornamented with a regimental cap badge or flash. The full-dress white helmet varied from regiment to regiment: several regiments had distinctive puggarees or hackles. On ceremonial occasions, the helmet was topped with a spike (for infantry and cavalry regiments, for the Army Ordnance Corps and the Royal Engineers) or a ball (for the Royal Artillery and other corps); and general officers staff officers and certain departmental officers, when in full dress, wore plumes on their helmets, similar to those worn on their full-dress cocked hats.[24]

George Orwell, commenting on the unproblematical use of slouch hats by Second World War British troops rather than the "essentially superstitious" use of pith helmets, wrote, "When I was in Burma I was assured that the Indian sun, even at its coolest [even in the early morning, and the sunless rainy season], had a peculiar deadliness which could only be warded off by wearing a helmet of cork or pith. 'Natives', their skulls being thicker, had no need of these helmets, but for a European, even a double felt hat was not a reliable protection."[25] The British Army formally abolished the tropical helmet (other than for ceremonial purposes) in 1948.

The Ethiopian Imperial Guard retained pith helmets as a distinctive part of their uniform until the overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie I in 1974. Imperial Guard units serving in the Korean War often wore these helmets when not in combat.

American naval officers could wear a pith helmet with the tropical khaki uniform. Most often, the pith helmet was worn by the U.S. Navy's Civil Engineer Corps.

Public use

Through the first half of the 20th century, the Wolseley pattern helmet was routinely worn with civil uniform by British colonial, diplomatic, and consular officials serving in 'hot climates'. It was worn with a gilt badge of the royal arms at the front. When worn by governors and governors-general, the helmet was topped by a 10-inch red and white swan-feather plume.[26] British diplomats in tropical postings, governors-general, governors and colonial officials continued to wear the traditional white helmets as part of their ceremonial white uniforms until Foreign and Commonwealth Office officials ceased to wear such dress in the late 20th century as an economy measure. The ceremonies marking the end of British rule in Hong Kong in 1997 featured the Royal Hong Kong Police Aide-de-camp to the Governor in a white Wolseley pith helmet with black and white feathers. It was the last occasion on which this style of headdress appeared as a symbol of the Empire.

Civilian use

Due to its popularity, the pith helmet became common civilian headgear for Westerners in the tropics and sub-tropics from the mid-19th century. The civilian pith helmet usually had the same dimensions and outline as its contemporary military counterpart but without decorative extras such as badges. It was worn by men and women, old and young, on formal and casual occasions, until the 1940s.[27] Both white and khaki versions were used. It was often worn together with civilian versions of khaki drill and bush jackets.

At the turn of the 20th century, there was a widespread assumption that wearing this form of head-dress was necessary for people of European origin to avoid sunstroke in the tropics. By contrast, indigenous peoples were assumed to have acquired relative immunity.[28] Modern medical opinion holds that some form of wide-brimmed but light headwear (such as a Panama hat, etc.) is highly advisable in strong sunlight for people of all ethnicities to avoid skin cancers and overheating.

Pith helmets began to decline in popularity in the mid-1950s. For example, they had become relatively uncommon in Francophone African colonies by 1955, despite their former conspicuous popularity among European visitors and expatriates there during the previous decade.[29]

Modern uses

Military and public uses

Netherlands

A dark blue pith helmet, similar to the British Home Service helmet, is worn with the ceremonial uniforms of the Garderegiment Fuseliers Prinses Irene and the Netherlands Marine Corps.[30]

United States

Throughout the Second World War, the U.S. Marine Corps, U.S. Navy, and the U. S. Army developed a cheaper, similar-looking alternative to the pith helmet, called the American fiber helmet, which was made from pressed fiber.[31] Some of the helmets were printed with a camouflage pattern.[32] The two main producers of the US military fiber pressed pith helmet were the International Hat Company and Hawley Products Company. Both companies had originally designed and manufactured several civilian models made from pressed fiber with a foil lining in the 1930s, aimed to be used by laborers who worked in the hot sun, from farms to road construction to other manual labor.[33]

The U.S. Marine Corps pith helmet (officially "Helmet, sun, rigid, fiber") has been used as a form of identification by rifle range cadres; similarly, rifle range instructors and drill instructors wear the campaign hat.[34] The U.S. Navy also authorized a plastic khaki sun helmet for wear by officers in tropical regions during the mid-20th century. It was decorated with a full-size officer's hat crest on the front.

White or light blue helmets of plastic material but traditional design are official optional uniform items worn today by letter carriers of the U.S. Postal Service to protect against sun and rain.

Vietnam

After the Second World War, the communist Viet Minh in French Indochina, and later the People's Army of Vietnam of the North, based their helmet design, called mũ cối, on the French pith helmet. Today it is still widely worn by civilians in Vietnam (mainly in the North, but its use declined sharply in 2007 when the motorbike helmet became mandatory for motorbike riders). In design, the Vietnamese model was similar to the pre-Second World War civilian type but covered in jungle green cloth or other colors depending on the army's branches (for example, blue for the Air Force), usually with a metal insignia at the front. It is considered a symbol of the Vietnamese Army.

Kenya

After the struggles for independence, including the Mau Mau Uprising, Kenya gained its independence from Britain in December 1963, riding the 'winds of change'. In the following year, after President Jomo Kenyatta's election in 1964, the pith helmet became a regulated hat of the uniform for provincial administrators and commissioners, who acted as representatives of the central government overseeing local management.

Originally, in Kenya and other African regions, the pith helmet was perceived as a product of reporters' exaggerations and misunderstood by readers. Travel books and magazines advised Europeans not to engage in outdoor activities without head coverings, claiming that exposure to direct tropical sunlight could cause their brains to deteriorate. While the articles may have been somewhat exaggerated, the pith helmet indeed protected against intense direct sunlight on the savanna, and its sturdy shell and liner shielded the head from collisions with branches in the jungle rainforest. The brim, resembling an eave, also served to prevent raindrops from entering the eyes or forming on glasses. Now, in addition to that, it has been left as a symbol of authority for free Africans.

Commonwealth realms

Several military units still use the pith helmet throughout the Commonwealth.

In the United Kingdom, the Royal Marines wear white Wolseley pattern helmets of the same general design as the old pith helmet as part of their number 1 or dress uniform. These date from 1912 in their present form and are made of natural cork covered in white cloth on the outside and shade green on the inside. Decoration includes a brass ball ornament at the top (a detail inherited from the Royal Marine Artillery), helmet plate, and chin chain.

The Home Service helmet is still worn by line infantry regiments in the United Kingdom today as part of full dress uniform. Although these units' wearing of full dress uniform largely ceased after the First World War, it continues to be worn by regimental bands, Corps of Drums, and guards of honour on ceremonial occasions. Such personnel are likewise directed to wear the Foreign Service helmet (either colonial pattern or Wolseley pattern according to regimental specification) when full dress uniform is worn "in hot weather overseas stations such as Cyprus".[35]

.jpg.webp)

Within the British Overseas Territories, a white Wolseley helmet with red and white swan-feather plume is occasionally worn by colonial governors when in white tropical uniform.[36] Since 2001, such dress has been provided only at the expense of the territory concerned and is no longer paid for by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.[37]

The Royal Gibraltar Regiment routinely wear the white pith helmet with a white tunic (in summer) and scarlet tunic (in winter).

The pith helmet is used by Australian military bands, such as the Army Band and the Band of the Royal Military College, Duntroon, as well as the New South Wales Mounted Police, and the Band of the South Australia Police.

A white Wolseley helmet forms a part of the Canadian Army's universal full-dress uniform, although specific units wear different headgear owing to authorized regimental differences.[38][39] In addition, the pith helmet is also worn by cadets at the Royal Military College of Canada for certain parades and special occasion.

In the Bahamas, pith helmets are worn by the Royal Bahamas Police Force Band.[40] A khaki or white pith helmet is part of the standard summer uniform of traffic officers in specific police departments in India. The pith helmet is also used by the Sri Lankan Police as part of their dress uniform.

Other countries

In the Dominican Republic, pith helmets with black pugarees were the standard duty headgear used by transit officers of the national police in the 1970s until the beginning of the 21st century, when these units were replaced by the creation of the Autoridad Metropolitana de Transporte (AMET) corps, which were issued dark green stetson hats instead.

In Greece, the Hellenic Navy band uses the pith helmet during its appearances (ex., at parades, when inspected by officials outside of churches, both events held during national feasts, etc.), with the Wolseley type one being used worn with full dress. It was possibly introduced at the beginning of the 20th century when the Hellenic Armed Forces were organized according to the French Army (the Hellenic Army) and the British Royal Navy (the Hellenic Navy).

.jpg.webp)

Modern Italian municipal police wear a helmet modeled on the Model 1928 tropical helmet of the Royal Italian Army for foot patrols in summer. These are made from white plastic with cork or pith interior lining and resemble the British Custodian helmet, though taller and narrower.

Pith helmets are worn by the Compagnie des Carabiniers du Prince of Monaco.

In the Philippines, some ceremonial units such as the Presidential Security Group and the guard of honor of the National Police use pith helmets.

They are also used by the King's Guards of the Royal Thai Army when on guard duty; a similar helmet but with plumes is used when in the full dress uniform with the plumes in uniform facings (similar to the bearskin).

White Wolseley helmets are worn by mounted Presidential Guard members in Harare, Zimbabwe, during the State Opening of the first session of Parliament each year.[41]

Civilian and commercial uses

The pith helmet has had a limited comeback in recent years, with their now novel appearance and genuine functionality making the headdress increasingly popular for gardening, hiking, safari, and other outdoor activities. Today's helmets are generally available in four basic types (see below). These have changed little since the early 1900s, except that for more effortless adjustment; the inner headband utilises hook-and-loop fasteners (e.g., Velcro) instead of the earlier brass pins. They can also be soaked in water to keep the wearer's head cool in hot weather and feature an adjustable chinstrap towards the front.

.jpg.webp)

(i) French pith helmet. This is the most functional of the helmets, with its wide brim providing more sun protection than the narrow-brimmed variations. This helmet is mostly made in Vietnam, where the design was inherited from French colonial patterns.

(ii) Indian pith helmet. The Indian model is almost the same as the French one but with a slightly narrower brim and a squarer dome. It shares with other helmets the ventilation "button" atop the dome.

(iii) African pith helmet, or safari helmet, is a variation mainly used in savanna or jungle regions of Africa. It is generally a khaki-grey colour with the same dimensions and shape as the Indian helmet described above.

(iv) Wolseley pith helmet. This variation of the helmet was named after (but not designed by) Field Marshal The 1st Viscount Wolseley,[42] an Anglo-Irish military commander, and widely used by the British Army and Colonial civil service from 1900. The Wolseley helmet differs from other pith helmets in having a more sloping brim with an apex at the front and back. The dome is also taller and more conical than the other more rounded variations. It is the helmet often portrayed as being worn by stereotypical "Gentleman Explorers".

In popular culture

Over the last century and a half, the helmet has become an iconic piece of apparel identified with western explorers, big game hunters, archaeologists, paleontologists, biologists, botanists, soldiers, and colonists throughout Africa, southern Asia and South America. It was popularized by Theodore Roosevelt in the first half of the 20th century, and by cinema in the second. Examples include:

- Many characters in Edgar Rice Burrough's Tarzan franchise. Among them is Jane Porter in the 1931, 1981, and 1999 films.

- Mr. Pompous (Dr. Mustache), an ecologist and animal caretaker in Jungle Emperor Leo, 1989.

- Dr. Schweitzer, a medical volunteer and Nobel Peace Prize winner from the biographical film Albert Schweitzer, 2009

- The Marvel Comics mad scientist and mercenary Klaw on Fantastic Four and Avengers: Earth's Mightiest Heroes.

- Van Pelt, a big game hunter, in Jumanji and the TV series based on it.

- Jack Black playing Professor Sheldon Oberon in Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle and Jumanji: The Next Level.

- Members of the British Army in the 1994 version of Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book, the war film Zulu and its prelude Zulu Dawn, and the Doctor Who episode Empress of Mars.

- Captain Cook on the Doctor Who episode The Greatest Show in the Galaxy.

- The poacher Betty on Widget the World Watcher

- The hammerhead shark-themed poacher and temple robber known as the Collector on Atomic Betty.

- Twilight Sparkle, Rainbow Dash, Fluttershy, Rarity, Pinkie Pie, List of My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic characters#The Cutie Mark Crusaders, and Daring Do on My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic and My Little Pony: Equestria Girls.

- The title characters on Yin Yang Yo on the episodes Scary Scary Quite Contrary and Carl of the Wild.

See also

Notes

- ↑ From Tagalog salakot, corrupted variously in Spanish, French, Italian, German, and English as salacco, shalakó, salakof, salakoff, or salakhoff

- ↑ The terms solar topee and solar topi are examples of folk etymology elaborations of the sola plant and are not etymologically related to "sun" or "solar"

References

- ↑ "pith helmet". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- 1 2 Alfredo R. Roces, et al., eds., Ethnic Headgear in Filipino Heritage: the Making of a Nation, Philippines: Lahing Pilipino Publishing, Inc., 1977, Vol. VI, pp. 1106–1107.

- 1 2 3 Antón, Jacinto (5 December 2013). "La romántica elegancia de Salacot". El País. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018 – via elpais.com.

- ↑ "AskOxford:pith helmet". Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Suciu, Peter. "Pith vs. Cork – Not One and the Same". Military Sun Helmets. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ↑ Philpott, Ian M. (2005). "9. Personnel". The Royal Air Force: An Encyclopedia of the Inter-War Years. The Trenchard Years, 1918–1929. Vol. I. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Aviation. p. 293. ISBN 1-84415-154-9.

- ↑ Montenegro, Arturo (28 June 2004). "La palabra salacot". Rinconente. Centro Virtual Cervantes. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ↑ Storey, Nicholas (2008). History of Men's Fashion: What the Well-dressed Man is Wearing. Casemate Publishers. p. 146. ISBN 9781844680375.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Suciu, Peter (17 December 2018). "The Proto-Sun Hats of the Far East". MilitarySunHelmets.com. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- 1 2 3 Manuel Buzeta y Felipe Bravo, Diccionario geografico, estadistico, historico de las Islas Filipinas, Charleston, South Carolina: 2011, Nabu Press, Vol. I, p. 241.

- ↑ Garnett, Lucy M.J. (1898). Courtney, W.L. (ed.). "The Philippine Islanders". The Fortnightly Review. Leonard Scott Publication Company. LXIV (July to December): 83–84.

- ↑ "Vestidos". Enseñanzas de la Campaña del Rif en 1909. Madrid: Talleres del Departmentósito de la Guerra. 1911.

- ↑ Hénon, Yann-Noël (26 August 2019). "A Salako on a banknote?". Numizon. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ↑ Lavuzelle, Charles. Les Troupes de Marine 1622–1984, ISBN 978-2-7025-0142-9 p.103

- ↑ "Military collection of Peter Suciu". Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- ↑ "British Experimental Helmets and Others". MilitarySunHelmets.com. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ↑ Barthorp. Michael. The Zulu War ISBN 0-7137-1469-7 p. 21

- ↑ Barnes, R.M. Military Uniforms of Britain and the Empire, First Sphere Books 1972

- ↑ "Wolseley pattern khaki helmet, 1943 (C) | Online Collection | National Army Museum, London".

- ↑ Chartrand, René (2012). The Canadian Corps in World War I. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 9781782009061.

- ↑ Haswell Miller, A.E. Vanished Armies, ISBN 978 0 74780-739-1

- ↑ Page 346 Militaria Magazine Avril 2014

- ↑ "Quanonline.com". quanonline.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ↑ Bates, S. The Wolseley Helmet in Pictures: From Omdurman to El Alamein.

- ↑ Orwell, George (20 October 1944). "As I Please". Tribune.

- ↑ 'Dress worn at Court', Lord Chamberlain's Office, first published in 1898.

- ↑ Gunther, John. Inside Africa, Hamish Hamilton Ltd 1955, p.708

- ↑ 1911 Edition, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Mercier, Paul (1965). Van den Berghe, Pierre (ed.). Africa: Social Problems of Change and Conflict. San Francisco: Chandler Publishing Company. p. 285. ASIN B000Q5VP8U.

- ↑ Kannik, Preben (1968). Military Uniforms of the World in Colour. Blandford Press Ltd. pp. 254–255. ISBN 0-71370482-9.

- ↑ Peter Suciu (2014-02-08). "What's In a Name? The Pressed Fiber Helmet". Archived from the original on 2015-07-15. Retrieved 2015-06-07.

- ↑ Peter Suciu (2014-03-28). "The Camouflage Pressed Fiber Helmet". Archived from the original on 2015-07-15. Retrieved 2015-06-08.

- ↑ Peter Suciu (2014-11-21). "The Origin of the Pressed Fiber Helmet – In Perspective". Archived from the original on 2015-07-04. Retrieved 2015-06-08.

- ↑ "Drill Instructor School: Campaign Cover". 2009-03-28. Archived from the original on 2009-06-25.

- ↑ E.g.: "Regimental Handbook" (PDF). www.army.mod.uk. Duke of Lancaster's Regiment, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ "New Governor : 'Challenges are crime and the economy'". The Royal Gazette. 2012-05-23. Archived from the original on 2014-03-20. Retrieved 2014-04-26.

- ↑ La Guardia, Anton (8 June 2001). "Sun slowly sets on uniform of Empire". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017.

- ↑ "6-1". Canadian Armed Forces Dress Instruction (PDF). Canadian Armed Forces. 1 June 2001. p. 211. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ "6-1". Canadian Armed Forces Dress Instruction (PDF). Canadian Armed Forces. 1 June 2001. p. 211. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ "Things to do in the Caribbean - the Bahamas".

- ↑ "Official opening of the First Session of the Eighth Parliament". herald.co.zw. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ↑ Carmen, W.Y. (1977). A Dictionary of Military Uniform. p. 137. ISBN 0-684-15130-8.

External links

Media related to Pith helmets at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pith helmets at Wikimedia Commons