Historic Tuckahoe Plantation | |

Tuckahoe's northern wing | |

| |

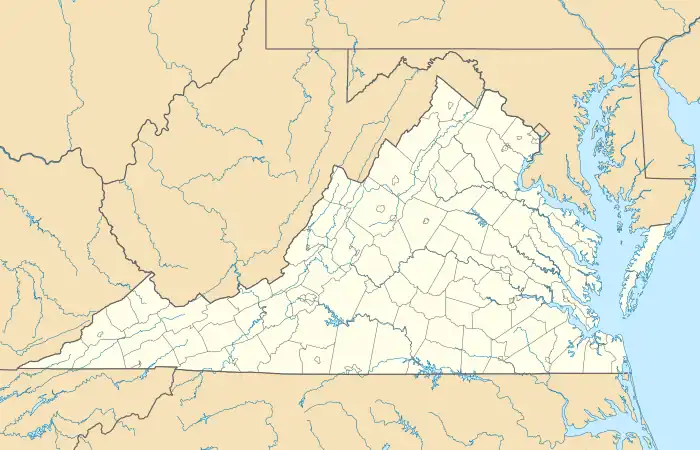

| Location | SE of Manakin near jct. of Rtes. 650 and 647, near Manakin, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°34′13.7″N 77°39′11.4″W / 37.570472°N 77.653167°W |

| Area | 568 acres (230 ha) |

| Built | 1712 |

| Architect | William Randolph |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| NRHP reference No. | 68000049 |

| VLR No. | 037-0033 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | November 22, 1968[1] |

| Designated NHLD | August 11, 1969[2] |

| Designated VLR | November 5, 1968[3] |

Tuckahoe, also known as Tuckahoe Plantation, or Historic Tuckahoe is located in Tuckahoe, Virginia on Route 650 near Manakin Sabot, Virginia, overlapping both Goochland and Henrico counties, six miles from the town of the same name. Built in the first half of the 18th century, it is a well-preserved example of a colonial plantation house, and is particularly distinctive as a colonial prodigy house. Thomas Jefferson is also recorded as having spent some of his childhood here. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1969.[2][4][5]

History

Thomas Randolph first settled at Tuckahoe around 1714 and is recorded as contributing to the construction of the local Dover Parish (also known as St James Parish) church in the early 1720s.[6][7] Randolph brought with him enslaved people, sufficient enough in number to be called a workforce, that he inherited from his father William Randolph's estate.[8][lower-alpha 1]

Thomas' son William Randolph III built the mansion.[10] He and his wife, Maria Judith Page, had three children (two girls and Thomas Mann Randolph Sr. born 1741). His wife died in 1744,[11] and the following year William died.[12] Randolph had added a codicil to his will asking that Peter Jefferson come to Tuckahoe Plantation and care for his three orphaned children.[13] Peter Jefferson and his wife Jane Randolph Jefferson, Randolph's cousin, moved from Shadwell in Charlottesville to Tuckahoe Plantation with their three daughters and two-year-old son Thomas. The Jeffersons and Randolph children lived together in the H-shaped home until 1752.[14] Peter Jefferson directed the activities of the plantation and its seven overseers, "retaining a connection to the estate" even during his famous expeditions to map the western part of the state and after he returned to his own plantation of Shadwell.[15]

Thomas Jefferson, who spent seven years of his childhood at Tuckahoe, came to formulate his moral viewpoint of slavery there:

The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this, and learn to imitate it…

The son of William Randolph III, Thomas Mann Randolph Sr. and his wife Anne Cary had thirteen children and she died in 1789. Shortly afterward, Thomas Mann Randolph Sr. remarried to Gabriella Harvie, the seventeen-year-old daughter of a Richmond attorney. Gabriella made significant changes to Tuckahoe, including painting the wooden paneling in the so-called "White Parlor", and insisted on naming her son (b. 1792) Thomas Mann Randolph Jr. despite the fact that the eldest son of Thomas Mann Randolph and Anne Cary (b. 1768) was already named Thomas Mann Randolph Jr. Thomas Mann Randolph Jr./II (1768-1828) moved to Edge Hill, Albemarle County, Virginia and went on to be a prominent statesman and governor of Virginia from 1819 to 1822. Thomas Mann Randolph Jr./III inherited Tuckahoe, but sold it for debts in 1830.[16]

The house passed through several families in the mid-19th century, but returned to the Randolphs in 1898 when it was sold to Harold Jefferson Coolidge and a consortium of Randolph and Jefferson descendants. In the 20th century, Tuckahoe featured prominently in an early test of the National Historic Preservation Act when the owners challenged Virginia's plan to route Virginia State Route 288 through the property (see Thompson v. Fugate, 347 F. Supp 120, E.D. Va. (1972)).

The house is currently occupied by owner/manager Addison B. Thompson and his wife Susan.

Main house and its exterior

William Randolph III constructed the current dwelling, now a National Historic Landmark, beginning in the mid-1730s.[10][11] Dendrochronology analysis indicates the timbers in the older (north) wing date to ca. 1733 and this is supported by archaeological evidence dating the north porch to ca. 1740. The north wing features pine and black walnut paneling with exquisite carvings and moldings. William Randolph then added a center hall and south wing, creating a unique "H" shape which was completed by 1740.[11] The main residence at Tuckahoe plantation is one of the "great plantations" of 18th-century Virginia.[10]

The two-story wood structure sits in its original spot, the only Randolph home to not be relocated. The structure forms an "H," with wings mirroring each other and connected by a central corridor. The entrances to the house are reached by flights of stairs and two porches. The stoop is covered by a projected pediment supported by simple wooden posts and is framed by a wooden railing. To either side of the entrance is a pair of windows as well as a central window over the entrance, each with dark shutters. Each two-sashed window contains 9 panes of glass. The gabled roof rests on a simple cornice line with dentil moldings. A large brick chimney rises from either side of the home.

The grounds

Outbuildings

A collection of outbuildings were located on Plantation Street of Tuckahoe.[17][lower-alpha 2] The buildings are arranged west of the mansion in a quadrangle. Food management and processing were performed in a storehouse, a smokehouse, and a brick kitchen,[17] which had a swinging crane and a dutch oven.[19] Slave quarters, an office, a toolhouse, and a barn are there.[17][19] There used to be an ice house and weaving room.[19] There were around 100 domestic workers, field hands, and skilled craftsmen who worked at Tuckahoe in the late 1740s.[20] In 1779, there was a stable built specifically for one horse named Shakespeare who was well-fed and pampered. A niche for a bed was constructed so that a black boy could sleep there through the night and ensure the health and comfort of the horse.[21]

Cemeteries of the Randolph, Wight, and current Ball/Thompson families are also on the grounds.

Slave quarters

The slave quarters at Tuckahoe were larger than most slave quarters, which could be as small as 12 by 8 feet. They were about 16 by 20 feet, but were divided into two units, which were separated by a central chimney. Each room had an exterior door.[22] Two later slave quarters include overhead lofts.[17]

Plantation life

Economy

Tuckahoe was 25,000 acres at its height. There were three mills on the property and Tuckahoe grew wheat and tobacco and raised livestock.[10] The main crop was tobacco, which was sent to London in barrels.[20]

Household and farm work

Household and farm work was performed by indentured servants and enslaved men, women, and children.[10] Indentured servants, generally brought from England, served as unpaid workers for a specific period of time. Enslaved people were held for their lives, and children of an enslaved woman were also enslaved at birth under partus sequitur ventrem.[23][lower-alpha 3]

In 1859, there were 62 bondspeople. A few worked in the house as domestic workers or cooks. One individual was a metalsmith. Most of the people worked in the fields. From the records of that time, children began working in the fields by age 11.[10][lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5] Relying on labor from enslaved people meant that planters and their families lived wealthy and comfortable lives.[20]

Clothing

Tuckahoe had a weaving room,[19] which meant that it was possible that workers on the plantation created fabric for clothing. It is also possible that they grew flax and spun threads to weave the fabric. Garments would have been sewn by designated enslaved people from their woven linen or people may have constructed their own clothing. Some planters, like Thomas Jefferson, provided fabric so that people would sew their own clothing.[27]

Residents

A woman named Harriet was among the last known African Americans born on Tuckahoe. She had a "clear recollection" of growing up on the plantation, which she recounted in 1915. Her husband, Wesley, was a ditcher.[10]

Levi Ellis was known to his family as a freed man from the Tuckahoe plantation. He purchased 49 acres in Goochland County, Virginia that he farmed with his wife Martha Jane Ellis. He was a founder of what was later called Ellisville, bordered by the Ellisville Bridge. He was also a founder, deacon, and Sunday School superintendent of the St. James Baptist Church. It was among the first black churches in the county and operated a school.[28][lower-alpha 6]

Interaction with other people

Bondspeople traveled among other plantations owned by the Jeffersons, Randolphs, and the Lewises, who were family members. Some slaveholders traveled with one or two enslaved people. People who had special skills, like carpentry, would sometimes work at other estates. There were a number of instances in which blacks at Tuckahoe communicated with those at Jefferson family plantations, including when Jeffersons moved to Tuckahoe and then back to Shadwell (following William Randolph's death).[29] In 1790, the Jeffersons visited Tuckahoe with Hemings family members.[30]

Song

At Monticello, the enslaved people had a song that mentions Tuckahoe. According to Martha Jefferson Randolph, the song refers to Thomas Mann Randolph Sr.:[31][lower-alpha 7]

- While old Colonel Tom lived and prospered,

- There was nothing but joy at Tuckahoe.

- Now that old Colonel Tom is dead and gone,

- No more joy for us at Tuckahoe.

Worship

Churches were built and operated by white people. Free blacks and enslaved people may have been able to worship in these churches, in separate space for blacks, until blacks established their own churches.[32] There was no church until 1720 when the parish of St. James was established. The Dover Church, closest to Tuckahoe, was built from 1720 to 1724. The first permanent minister in residence was Rev. William Douglass, who began preaching 1750.[33] Dover Mines Baptist Church was established for blacks from a dormant mining building. It is now the First Baptist Church in Manakin, Virginia.[32]

Sale

Portions of the Randolph's Tuckahoe plantation were subdivided into smaller tracts and sold. Upon completion of an anticipated sale in 1842, enslaved people were to be put up for sale.[34]

The nearby city of Richmond was the largest seller of enslaved people in Virginia. When enslaved people were sold, it meant that communities and families were likely dispersed to different places.[35] It was common for people to be separated from their spouses and children, perhaps for the rest of their lives.[35] People were taken from the plantation and put into jails or slave pens of slave traders. They could have been there for weeks and may have been subject to physical inspections. When they were auctioned, it was possible that they were sold to another trader or ultimately sold to work plantations in the Deep South.[35]

Runaways

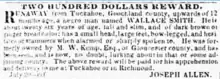

A carpenter named Gabriel or Gabe ran away from Tuckahoe on December 10, 1783. An advertisement by Thomas M. Randolph offered a reward of $20 for Gabriel and $5 for the horse that he took for his escape. He was formerly enslaved by Col. Charles Carter of Ludlow.[36] Bob Christian ran away on January 5, 1836. He had a wife in New Kent County, a mother in Richmond, and other relatives in Chickahominy. Tuckahoe's plantation owner E.L. Wight offered $20 for his return.[37] By 1851, M.W. Kemp of Gloucester County sold Wallace Smith to Joseph Allen of Tuckahoe. Smith ran away and was expected to be in Gloucester. A $200 (equivalent to $7,035 in 2022) reward was offered for his return.[38]

Freedom

Slavery continued until the passage of the 13th Amendment that abolished slavery in 1865. There were laws enacted and other practices that limited African Americans rights and opportunities after the Emancipation Proclamation.[10]

Some of the people who were emancipated following the American Civil War lived on Tuckahoe into the turn of the 20th century. They were paid a salary and lived in the original quarters on the property.[10]

Others, like Levi Ellis, settled into a community of black people, like New Town in the Three Square area, and, in the eastern part of the county, Ellisville and Gordonstown.[39] Once free, blacks in Virginia competed directly with white people for work in their trades. Many freedmen had a number of customers rather than being tied to one employer, which might recommence a paternalistic relationship.[40]

Legacy

In February 2019, three women painted the message "we profit off slavery" in red on a sign and pillar at Tuckahoe. The anonymous group who took responsibility for the message said that it was a reminder of "Virginia's troubled history."[41] It happened during the same period that protestors met at the Virginia State Capitol and outside the Executive Mansion and called on Gov. Northam to resign. A fountain at Capitol Square was vandalized when red dye was poured into the water.[42]

Notes

- ↑ William Randolph, the immigrant, purchased large tracts of land over his lifetime that he then gave to his sons upon his death. The large land holdings were divided up so that the sons had adjoining plantations.[9]

- ↑ Plantations generally had out-buildings that were used by enslaved people to process food, like henhouses and meat houses. There were also carriage houses and stables for horses.[18]

- ↑ Africans were first brought to Colonial Virginia in 1619, but laws making the practice legal were not enacted until 1661.[23]

- ↑ As an example of how children were put to work on a plantation, Thomas Jefferson recorded his strategy in his Farm Book. Until the age of 10, children served as nurses. When the plantation grew tobacco, children were at a good height to remove and kill tobacco worms from the crops.[24] Once he began growing wheat, fewer people were needed to maintain the crops, so Jefferson established manual trades. He stated that children "go into the ground or learn trades" When girls were 16, they began spinning and weaving textiles. Boys made nails from age 10 to 16. In 1794, Jefferson had a dozen boys working at the nailery.[24] While working at the nailery, boys received more food and may have received new clothes if they did a good job. After the nailery, boys became blacksmiths, coopers, carpenters, or house servants.[24]

- ↑ In Goochland County, most of the residents were black bondspeople, owned by the largest plantations, by 1789. In 1790, there were 4,656 enslaved people and 257 free black people and 4,140 whites. Over time, there was an increase in the percentage of enslaved people, while the population of whites diminished. There were 5,845 slave and 644 free blacks—while the number of whites went down to 3,865 by 1850.[25] By 1850, there were 644 free blacks in Virginia. Those who were freed during the antebellum period built modest homes, similar to those of white people with low income.[26]

- ↑ In 2008, a historical marker was established at the Ellisville Bridge by the Goochland County Historical Society.[28]

- ↑ Tuckahoe was intertwined with the lives of the Jeffersons, through the time that Peter Jefferson and his family lived at the plantation when William Randolph’s children were orphaned, and also through the marriage of Martha Jefferson to Thomas Mann Randolph.[31]

References

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- 1 2 "Tuckahoe". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

- ↑ "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ↑ James Dillon (October 9, 1974), National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Tuckahoe Plantation (pdf), National Park Service and Accompanying 14 photos, aerial and exterior and interior, from 1968, 1972, and 1974 (32 KB)

- ↑ Charles W. Snell (March 19, 1971), National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Tuckahoe Plantation House (Thomas Jefferson Boyhood Home) / Tuckahoe (PDF), National Park Service

- ↑ Glenn, Thomas Allen, ed. (1898). "The Randolphs: Randolph Genealogy". Some Colonial Mansions: And Those Who Lived In Them : With Genealogies Of The Various Families Mentioned. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Henry T. Coates & Company. pp. 430–459.

- ↑ Tuckahoe Plantation Archived 2010-12-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Tuckahoe". Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ↑ Anderson, Jefferson Randolph (1937). "Tuckahoe and the Tuckahoe Randolphs". Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society. 35 (110): 30–32. ISSN 2328-8183. JSTOR 23371542.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "The History". Historic Tuckahoe. March 4, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Malone, Dumas, Jefferson the Virginian, St. Martin’s Press, 1948, Volume 1, p. 19

- 1 2 Meacham, Jon (2012). Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 6–10. ISBN 978-0-679-64536-8.

- ↑ Malone, p. 19

- ↑ Malone, pp. 20, 26

- ↑ Malone, p. 20, n48

- ↑ Randolph, Thomas M. (August 28, 1829). "A Valuable and Beautiful Farm for Sale". No. Vol. VI, No. 65. Pleasants, Abbot, & Co. The Constitutional Whig (Richmond, Va.). Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Tuckahoe Plantation Nomination Form" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. 1974. p. 6. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ↑ Worsham, Gibson (2003). "A Survey of Historic Architecture in Goochland County, Virginia" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. p. 79.

- 1 2 3 4 "Estates on James Retain Original Features". The Times Dispatch. April 24, 1949. p. 122. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Miller, Brandon Marie (September 2011). Thomas Jefferson for Kids. Chicago Review Press. pp. 1, 2. ISBN 978-1-56976-942-3.

- ↑ "Tuckahoe". Richmond Enquirer. October 28, 1845. p. 4. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ↑ Delle, James A.; Fellows, Kristen R. (2012). "A Plantation Transplanted: Archaeological Investigations of a Piedmont-Style Slave Quarter at Rose Hill, Geneva, New York". Northeast Historical Archaeology. 41 (4): 64. doi:10.22191/neha/vol41/iss1/4 – via The Open Repository @ Binghamton.

- 1 2 Rose, Willie Lee Nichols (1999). A Documentary History of Slavery in North America. University of Georgia Press. pp. 15–22, 25. ISBN 978-0-8203-2065-6.

- 1 2 3 "The Dark Side of Thomas Jefferson". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ↑ Worsham, Gibson (2003). "A Survey of Historic Architecture in Goochland County, Virginia" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. pp. 22, 33.

- ↑ Worsham, Gibson (2003). "A Survey of Historic Architecture in Goochland County, Virginia" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. p. 76.

- ↑ "Slave Clothing and Adornment in Virginia". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- 1 2 Purdue, Sharon (September 2009). "Ellisville Bridge Historic Marker" (PDF). Goochland History. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ↑ Kern, Susan (September 21, 2010). The Jeffersons at Shadwell. Yale University Press. pp. 100, 161, 294 (#9). ISBN 978-0-300-15570-9.

- ↑ Kierner, Cynthia A. (May 14, 2012). Martha Jefferson Randolph, Daughter of Monticello: Her Life and Times. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8078-8250-4.

- 1 2 Kern, Susan (September 21, 2010). The Jeffersons at Shadwell. Yale University Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-300-15570-9.

- 1 2 Worsham, Gibson (2003). "A Survey of Historic Architecture in Goochland County, Virginia" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. p. 82.

- ↑ Anderson, Jefferson Randolph (1937). "Tuckahoe and the Tuckahoe Randolphs". Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society. 35 (110): 29–59. ISSN 2328-8183. JSTOR 23371542.

- ↑ "Extensive and Valuable James River Lands". Richmond Enquirer. September 13, 1842. p. 1. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Slave Sales". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ↑ "Clipped From The Virginia Gazette, or, The American Advertiser". The Virginia Gazette, or, The American Advertiser. January 3, 1784. p. 3. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Twenty Dollars Reward". Richmond Enquirer. January 23, 1836. p. 1. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Two Hundred Dollars Reward". Richmond Enquirer. November 23, 1852. p. 1. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ↑ Worsham, Gibson (2003). "A Survey of Historic Architecture in Goochland County, Virginia" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. pp. 88, 91.

- ↑ Ely, Melvin Patrick (December 1, 2010). Israel on the Appomattox: A Southern Experiment in Black Freedom from the 1790s Through the Civil War. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-0-307-77342-5.

- ↑ "3 women wanted for painting 'We profit off slavery' at Tuckahoe Plantation". February 19, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Vandals paint 'We profit off slavery' at Tuckahoe Plantation". February 19, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

Further reading

- Masson, Kathryn and Brooke, Steven (photographer); Historic Houses of Virginia: Great Plantation Houses, Mansions, and Country Places; Rizzoli International Publications; New York City, New York; 2006

External links

Media related to Tuckahoe Plantation at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tuckahoe Plantation at Wikimedia Commons- Tuckahoe, at National Park Service

- James River Plantations, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- Tuckahoe, Goochland County, 4 photos at Virginia DHR

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. VA-712, "Tuckahoe Plantation, River Road, Richmond vicinity, Manakin vicinity, Goochland County, VA", 8 measured drawings