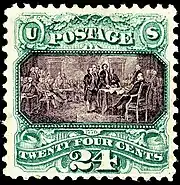

%252C_by_John_Trumbull.jpg.webp) John Trumbull's 1819 painting, Declaration of Independence, depicts the five-man drafting committee of the Declaration of Independence presenting their work to the Second Continental Congress | |

| Date | August 2, 1776 |

|---|---|

| Venue | Independence Hall |

| Location | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 39°56′56″N 75°09′00″W / 39.948889°N 75.15°W |

| Participants | Delegates to the Second Continental Congress |

The signing of the United States Declaration of Independence occurred primarily on August 2, 1776, at the Pennsylvania State House in Philadelphia, later to become known as Independence Hall. The 56 delegates to the Second Continental Congress represented the 13 colonies, 12 of which voted to approve the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776. The New York delegation abstained because they had not yet received instructions from Albany to vote for independence. The Declaration proclaimed the signatory colonies were now "free and independent States", no longer colonies of the Kingdom of Great Britain and, thus, no longer a part of the British Empire. The signers’ names are grouped by state, with the exception of John Hancock, as President of the Continental Congress; the states are arranged geographically from south to north, with Button Gwinnett from Georgia first, and Matthew Thornton from New Hampshire last.

The final draft of the Declaration was approved by the Continental Congress on July 4, although the date of its signing has long been disputed. Most historians have concluded that it was signed on August 2, 1776, nearly a month after its adoption, and not on July 4 as is commonly believed.

Date of signing

The Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, with 12 of the 13 colonies voting in favor and New York abstaining. The date that the Declaration was signed has long been the subject of debate. Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams all wrote that it was signed by Congress on the day when it was adopted on July 4, 1776.[1] That assertion is seemingly confirmed by the signed copy of the Declaration, which is dated July 4. Additional support for the July 4 date is provided by the Journals of the Continental Congress, the official public record of the Continental Congress. The proceedings for 1776 were first published in 1777, and the entry for July 4 states that the Declaration was engrossed and signed on that date (the official copy was handwritten by Timothy Matlack).[2]

In 1796, signer Thomas McKean disputed that the Declaration had been signed on July 4, pointing out that some signers were not present, including several who were not even elected to Congress until after that date.[3] "No person signed it on that day nor for many days after", he wrote.[4] His claim gained support when the Secret Journals of Congress were published in 1821.[5] The Secret Journals contained two previously unpublished entries about the Declaration.

On July 15, New York's delegates got permission from their convention to agree to the Declaration.[6] The Secret Journals entry for July 19 reads:

Resolved That the Declaration passed on the 4th be fairly engrossed on parchment with the title and stile of "The unanimous declaration of the thirteen united states of America" & that the same when engrossed be signed by every member of Congress.[7]

The entry for August 2 states:

The declaration of Independence being engrossed & compared at the table was signed by the Members.[7]

In 1884, historian Mellen Chamberlain argued that these entries indicated that the famous signed version of the Declaration had been created following the July 19 resolution, and had not been signed by Congress until August 2.[8] Subsequent research has confirmed that many of the signers had not been present in Congress on July 4, and that some delegates may have added their signatures even after August 2.[9] Neither Jefferson nor Adams ever wavered from their belief that the signing ceremony took place on July 4, yet most historians have accepted the argument which David McCullough articulates in his biography of John Adams: "No such scene, with all the delegates present, ever occurred at Philadelphia."[10]

Legal historian Wilfred Ritz concluded in 1986 that about 34 delegates signed the Declaration on July 4, and that the others signed on or after August 2.[11] Ritz argues that the engrossed copy of the Declaration was signed by Congress on July 4, as Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin had stated, and that it was implausible that all three men had been mistaken.[12] He believes that McKean's testimony was questionable,[13] and that historians had misinterpreted the July 19 resolution. According to Ritz, this resolution did not call for a new document to be created, but rather for the existing one to be given a new title, which was necessary after New York had joined the other 12 states in declaring independence. He reasons that the phrase "signed by every member of Congress" in the July 19 resolution meant that delegates who had not signed the Declaration on the 4th were now required to do so.[14]

In an 1811 letter to Adams, Benjamin Rush recounted the signing in stark fashion, describing it as a scene of "pensive and awful silence". Rush said the delegates were called up, one after another, and then filed forward somberly to subscribe what each thought was their ensuing death warrant.[15] He related that the "gloom of the morning" was briefly interrupted when the rotund Benjamin Harrison of Virginia said to a diminutive Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, at the signing table, "I shall have a great advantage over you, Mr. Gerry, when we are all hung for what we are now doing. From the size and weight of my body I shall die in a few minutes and be with the Angels, but from the lightness of your body you will dance in the air an hour or two before you are dead."[15] According to Rush, Harrison’s remark "procured a transient smile, but it was soon succeeded by the Solemnity with which the whole business was conducted.”[15]

List of signers

Fifty-six delegates eventually signed the Declaration of Independence:

Signer details

| Part of a series on the |

| American Revolution |

|---|

%252C_by_John_Trumbull.jpg.webp) Declaration of Independence (painting) |

|

|

Eight delegates never signed the Declaration, out of about 50 who are thought to have been present in Congress during the voting on independence in early July 1776:[16] John Alsop, George Clinton, John Dickinson, Charles Humphreys, Robert R. Livingston, John Rogers, Thomas Willing, and Henry Wisner.[17] Clinton, Livingston, and Wisner voted for independence, but were attending to duties away from Congress when the signing took place. Rogers, who had also voted for the resolution of independence, was no longer a delegate on August 2. Willing and Humphreys voted against the resolution of independence and were replaced in the Pennsylvania delegation before the August 2 signing. Alsop favored reconciliation with Great Britain and so resigned rather than add his name to the document.[18] Dickinson refused to sign, believing the Declaration premature, but he remained in Congress. George Read had voted against the resolution of independence, and Robert Morris had abstained—yet they both signed the Declaration.

The most famous signature on Timothy Matlack's engrossed copy is that of John Hancock, who presumably signed first as President of Congress.[19] Hancock's large, flamboyant signature became iconic, and John Hancock emerged in the United States as an informal synonym for "signature".[20] Future presidents Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were among the signatories. Edward Rutledge (age 26) was the youngest signer and Benjamin Franklin (age 70) the oldest.

Some delegates were away on business when the Declaration was debated, including William Hooper[22] and Samuel Chase, but they were back in Congress to sign on August 2. Other delegates were present when the Declaration was debated but added their names after August 2, including Lewis Morris, Oliver Wolcott, Thomas McKean, and possibly Elbridge Gerry. Richard Henry Lee and George Wythe were in Virginia during July and August, but returned to Congress and signed the Declaration probably in September and October, respectively.[23]

New delegates joining the Congress were also allowed to sign. Eight men signed the Declaration who did not take seats in Congress until after July 4: Matthew Thornton, William Williams, Benjamin Rush, George Clymer, James Smith, George Taylor, George Ross, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton.[24] Matthew Thornton did not take a seat in Congress until November.[25] By the time that he signed it, there wasn't any space for his name next to the other New Hampshire delegates, so he placed his signature at the end of the document.[26]

The first published version of the Declaration was the Dunlap broadside. The only names on that version were Congress President John Hancock and Secretary Charles Thomson, and those names were printed rather than signatures. The public did not learn who had signed the engrossed copy until January 18, 1777, when the Congress ordered that an "authenticated copy" be sent to each of the 13 states, including the names of the signers.[27] This copy is called the Goddard Broadside; it was the first to list all the signers[28] except for Thomas McKean, who may not have signed the Declaration until after the Goddard Broadside was published. Congress Secretary Charles Thomson did not sign the engrossed copy of the Declaration, and his name doesn't appear on the Goddard Broadside, even though it does appear on the Dunlap broadside.

Legacy

Various legends emerged years later concerning the signing of the Declaration, when the document had become an important national symbol. In one famous story, John Hancock supposedly said that Congress, having signed the Declaration, must now "all hang together", and Benjamin Franklin replied: "Yes, we must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately." The earliest known version of that quotation in print appeared in a London humor magazine in 1837.[29]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Warren, "Fourth of July Myths", pp. 242–43

- ↑ Warren, "Fourth of July Myths", p. 246; Burnett, Continental Congress, p. 192

- ↑ Hazelton, Declaration History, pp. 299–302; Burnett, Continental Congress, p. 192

- ↑ Hazelton, Declaration History, p. 302

- ↑ Warren, "Fourth of July Myths", pp. 243–45

- ↑ "Unsullied by Falsehood: The Signing". declaration.fas.harvard.edu.

- 1 2 U.S. Continental Congress, Secret Journals vol. 1, p. 46

- ↑ Warren, "Fourth of July Myths", pp. 245–46

- ↑ Hazelton, Declaration History, pp. 208–19; Wills, Inventing America, p. 341

- ↑ Strauss, Valerie (July 2, 2014). "What you know about July 4th is wrong". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ↑ Ritz, "Authentication", p. 194

- ↑ Ritz, "Authentication", p. 182

- ↑ Ritz, "Authentication", pp. 198–200

- ↑ Ritz, "Authentication", pp. 190–200

- 1 2 3 "Benjamin Rush to John Adams, July 20, 1811". National Park Service. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ↑ Friedenwald (Interpretation and Analysis, p. 143) says that 45 delegates can be confirmed as present on July 4, and that another four might have been.

- ↑ Friedenwald (Interpretation, p. 149) gives the number of non-signers as seven, not counting Dickinson, who absented himself for the final votes.

- ↑ Hazelton, Declaration History, pp. 525–26

- ↑ Hazelton, Declaration History, p. 209

- ↑ Merriam-Webster online; Dictionary.com.

- ↑ Malone, Story of the Declaration, p. 90

- ↑ Fradin, The Signers, 112.

- ↑ Friedenwald, Interpretation, p, 148

- ↑ Friedenwald (Interpretation, p. 149) lists seven men; he does not include Charles Carroll of Carrollton, who had been working as an emissary for Congress. He did not become an official member of the Maryland delegation until July 4, and did not take his seat as a delegate until July 18. (Hazelton, Declaration History, pp. 529, 587)

- ↑ The U.S. State Department (1911), The Declaration of Independence, 1776, pp. 10, 11.

- ↑ Friedenwald, Interpretation, p. 150

- ↑ Warren, "Fourth of July Myths", p. 247; Hazelton, Declaration History, p. 284; Friedenwald, Interpretation, p. 137, where the date is misprinted as January 8, but correct on page 150.

- ↑ Friedenwald, Interpretation, p. 137

- ↑ "The Gurney Papers". The New Monthly Magazine and Humorist (Part 1): 17. 1837. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

Sources

- Boyd, Julian P., ed. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 1. Princeton University Press, 1950.

- Boyd, Julian P. "The Declaration of Independence: The Mystery of the Lost Original". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 100, number 4 (October 1976), 438–67.

- Burnett, Edward Cody. The Continental Congress. New York: Norton, 1941.

- Friedenwald, Herbert. The Declaration of Independence: An Interpretation and an Analysis. New York: Macmillan, 1904. Accessed via the Internet Archive.

- Hazelton, John H. The Declaration of Independence: Its History. Originally published 1906. New York: Da Capo Press, 1970. ISBN 0-306-71987-8. 1906 printing available on Google Book Search

- Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. New York: Knopf, 1997. ISBN 0-679-45492-6.

- Malone, Dumas. The Story of the Declaration of Independence. New York: Oxford University Press, 1975. A picture book with text by a leading Jefferson scholar.

- Ritz, Wilfred J. "The Authentication of the Engrossed Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776". Law and History Review 4, no. 1 (Spring 1986): 179–204.

- United States Continental Congress. Secret journals of the acts and proceedings of Congress, from the first meeting thereof to the dissolution of the Confederation, vol. 1, p. 46. Boston: Thomas B. Wait, 1820.

- Warren, Charles. "Fourth of July Myths." The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, vol. 2, no. 3 (July 1945): 238–72.

- Wills, Garry. Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1978. ISBN 0-385-08976-7.