| Battle of Quebec | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

British and Canadian forces attacking Arnold's column in the Sault-au-Matelot, Charles William Jefferys | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,800[2] | 1,200[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 19 killed and wounded[4][5] |

84 killed and wounded 431 captured[6][4] | ||||||

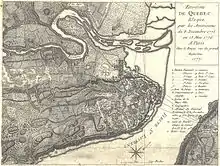

The Battle of Quebec (French: Bataille de Québec) was fought on December 31, 1775, between American Continental Army forces and the British defenders of Quebec City early in the American Revolutionary War. The battle was the first major defeat of the war for the Americans, and it came with heavy losses. General Richard Montgomery was killed, Benedict Arnold was wounded, and Daniel Morgan and more than 400 men were taken prisoner. The city's garrison, a motley assortment of regular troops and militia led by Quebec's provincial governor, General Guy Carleton, suffered a small number of casualties.

Montgomery's army had captured Montreal on November 13, and early in December they became one force that was led by Arnold, whose men had made an arduous trek through the wilderness of northern New England. Governor Carleton had escaped from Montreal to Quebec, the Americans' next objective, and last-minute reinforcements arrived to bolster the city's limited defenses before the attacking force's arrival. Concerned that expiring enlistments would reduce his force, Montgomery made the end-of-year attack in a blinding snowstorm to conceal his army's movements. The plan was for separate forces led by Montgomery and Arnold to converge in the lower city before scaling the walls protecting the upper city. Montgomery's force turned back after he was killed by cannon fire early in the battle, but Arnold's force penetrated further into the lower city. Arnold was injured early in the attack, and Morgan led the assault in his place before he became trapped in the lower city and was forced to surrender. Arnold and the Americans maintained an ineffectual blockade of the city until spring, when British reinforcements arrived.

Background

Shortly after the American Revolutionary War broke out in April 1775, a small enterprising force led by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold captured the key Fort Ticonderoga on May 10. Arnold followed up the capture with a raid on Fort Saint-Jean not far from Montreal, alarming the British leadership there.[7]

These actions stimulated both British and rebel leaders to consider the possibility of an invasion of the Province of Quebec by the rebellious forces of the Second Continental Congress, and Quebec's governor, General Guy Carleton, began mobilizing the provincial defenses. The British forces in Canada consisted of three regiments, with the 8th Regiment holding various forts around the Great Lakes and the 7th and 26th regiments guarding the St. Lawrence river valley.[8] Apart from these regiments, the only forces available to the Crown were about 15,000 men of the militia and the 8,500 or so warriors from the various Indian tribes in the northern district of the Department of Indian Affairs.[9] The largely Canadien militia and many of the Indian tribes were regarded as lukewarm in their loyalty to the Crown.[10]

Both the Americans and the British misunderstood the nature of Canadien (as French Canadians were then known) society.[11] The feudal nature of Canadien society with the seigneurs and the Catholic Church owning the land led the British to assume the habitants – as the tenant farmers who made up the vast majority of Quebec's population were known – would deferentially obey their social superiors while the Americans believed that the habitants would welcome them as liberators from their feudal society. In fact, the habitants, despite being tenant farmers, tended to display many of the same traits displayed by the farmers in the 13 colonies who mostly owned their land, being described variously as individualistic, stubborn, and spirited together with a tendency to be rude and disrespectful of authority figures if their actions were seen as unjust.[11] Most of the habitants wanted to be neutral in the struggle between Congress vs. the Crown, just wanting to live their lives in peace.[11] Carleton's romanticized view of Canadien society led him to exaggerate the willingness of the habitants to obey the seigneurs as he failed to understand that the habitants would only fight for a cause that they saw as being in their own interests.[12] A large number of the Canadiens still clung to the hope that one day Louis XVI would reclaim his kingdom's lost colony of New France, but until then, they wanted to be left alone.[13]

The memory of Pontiac's War in 1763 had made most of the Indians living in the Ohio River valley, the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River valley distrustful of all whites, and most of the Indians in the region had no desire to fight for either Congress or the Crown.[14] Only the Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois, living in their homeland of Kaniekeh (modern upstate New York) were regarded as willing to fight for the Crown, and even then some of the Six Nations like the Oneida and the Tuscarora were already negotiating with the Americans.[10] The Catholic Haudenosaunee living outside of Montreal—the so-called Seven Nations of Canada—were traditionally allies of the French and their loyalty to the British Crown was felt to be very shallow.[10] Both Arnold and Allen argued to Congress that the British forces holding Canada were weak, that the Canadiens would welcome the Americans as liberators and an invasion would require only 2,000 men.[15] Taking Canada would eliminate any possibility of the British using it as a base to invade New England and New York.[15]

.jpg.webp)

After first rejecting the idea of an attack on Quebec, the Congress authorized the Continental Army's commander of its Northern Department, Major General Philip Schuyler, to invade the province if he felt it necessary. On 27 June 1775 approval for an invasion of Canada was given to Schuyler.[15] As part of an American propaganda offensive, letters from Congress and the New York Provincial Assembly were circulated throughout the province, promising liberation from their oppressive government.[16] Benedict Arnold, passed over for command of the expedition, convinced General George Washington to authorize a second expedition through the wilderness of what is now the state of Maine directly to Quebec City, capital of the province.[17] The plan approved by Congress called for a two-pronged attack with 3,000 men under Schuyler going via Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River valley to take Montreal while 1,050 men under Arnold would march up the Kennebec River valley, over the Height of Land and then down the Chaudière River valley to take Quebec City.[18]

The Continental Army began moving into Quebec in September 1775. Richard Montgomery, heading the American vanguard took Ile-aux-Noix on 2 September 1775.[18] Its goal, as stated in a proclamation by General Schuyler, was to "drive away, if possible, the troops of Great Britain" that "under the orders of a despotic ministry ... aim to subject their fellow-citizens and brethren to the yoke of a hard slavery."[19] On 16 September 1775, the sickly Schuyler handed over the command of his army to Montgomery.[18] Brigadier General Richard Montgomery led the force from Ticonderoga and Crown Point up Lake Champlain, successfully besieging Fort St. Jean, and capturing Montreal on November 13. Arnold led a force of 1,100 men from Cambridge, Massachusetts on the expedition through Maine towards Quebec shortly after Montgomery's departure from Ticonderoga.[20]

One significant expectation of the American advance into Quebec was that the large French Catholic Canadien population of the province and city would rise against British rule. Since the British took control of the province, during the French and Indian War in 1760, there had been difficulties and disagreements between the local French Catholics and the Protestant English-speaking British military and civilian administrations. However, these tensions had been eased by the passage of the Quebec Act of 1774, which restored land and many civil rights to the Canadiens (an act which had been condemned by the thirteen rebelling colonies). The English-speaking "Old Subjects" living in Montreal and Quebec City (in contrast to the French-speaking "New Subjects") came mostly from Scotland or the 13 colonies, and they tried to dominate the Quebec colony both politically and economically, clashing with the long-established Canadien elite.[21] James Murray, the first Governor of Quebec, had described the "Old Subject" businessmen who arrived in his colony as "adventurers of mean education...with their fortunes to make and little Sollicitous about the means".[11] Carleton for his part felt the complaints by the Canadiens about the "Old Subjects" as greedy and unscrupulous businessmen were largely merited.[11] As a member of Ireland's Protestant Ascendancy, Carleton found much to admire in Quebec which reminded him of his native Ireland, as both places were rural, deeply conservative Catholic societies.[22] The majority of Quebec's French inhabitants chose not to play an active role in the American campaign, in large part because, encouraged by their clergy, they had come to accept British rule with its backing of the Catholic Church and preservation of French culture.[23]

Many of the "Old Subjects" saw the Quebec Act as a betrayal by the Crown as it granted equality to the Canadiens, most notably by allowing Roman Catholic men to vote and hold office, which ended the hopes of the "Old Subjects" to dominate Quebec politically.[11] Many of the English-speaking and Protestant "Old Subjects" were the ones who served as "fifth column" for the Americans rather than the French-speaking Roman Catholic "New Subjects" as the many "Old Subject" businessmen had decided that an American victory was their best hope of establishing Anglo-Protestant supremacy in Quebec.[11] Prominent "Old Subject" businessmen such as Thomas Walker, James Price, William Heywood and Joseph Bindon in Montreal together with John McCord, Zachary Macaulay, Edward Antill, John Dyer Mercier and Udnay Hay in Quebec City all worked for an American victory by providing intelligence and later money for the Continental Army.[11] Much of the American assessment that Canada could be easily taken was based on letters from "Old Subject" businessmen asking for the Americans to liberate them from the rule of the Crown which had given the Canadiens equality, and somewhat contradictorily also claiming that the Canadiens would rise up against the British if the Americans entered Quebec.[11]

British preparations

Defense of the province

General Carleton had begun preparing the province's defenses immediately on learning of Arnold's raid on St. Jean. On 9 June 1775 Carleton proclaimed martial law and called out the militia.[24] At Montreal, Carleton found that there were six hundred men of the 7th Foot Regiment fit for duty, but he complained that there were no warships on the St. Lawrence, the forts around Montreal in a state of disrepair and though the seigneury and the Catholic Church were loyal to the Crown, most of the habitants appeared indifferent.[24] Although Carleton concentrated most of his modest force at Fort St. Jean, he left small garrisons of British regular army troops at Montreal and Quebec.[25] To provide more manpower, Carleton raised the Royal Highland Emigrants Regiment, whom he recruited from the Scottish Highland immigrants in Quebec.[26] The commander of the Royal Highland Emigrants, Allan Maclean, was a Highlander who had fought for the Jacobites in the rebellion of 1745, and turned out to be Carleton's most aggressive subordinate in the campaign of 1775–76.[27] On 26 July 1775, Carleton met Guy Johnson, the superintendent of the northern district of the Indian Department together with an Indian Department official, Daniel Claus, and a Mohawk war chief Joseph Brant.[28] Johnson, Claus and Brant had brought with them some 1, 600 warriors whom they proposed to lead into a raid into New England, arguing that this was the best way of keeping the Americans engaged and out of Canada.[28] Carleton declined the offer and ordered most of the Indians home, saying he did not want the Indians involved in this war, whom he regarded as savages who he believed would commit all sorts of atrocities against the white population of New England.[29] Despite his dislike of Indians, whom he considered to be undisciplined and prone to brutality, Carleton employed at least 50 Indians as scouts to monitor the American forces as no one else could operate in the wilderness as scouts as well as the Indians.[26]

Carleton followed the American invasion's progress, occasionally receiving intercepted communications between Montgomery and Arnold. Lieutenant Governor Hector Cramahé, in charge of Quebec's defenses while Carleton was in Montreal, organized a militia force of several hundred to defend the town in September. He pessimistically thought they were "not much to be depended on", estimating that only half were reliable.[30] Cramahé also made numerous requests for military reinforcements to the military leadership in Boston, but each of these came to nought. Several troop ships were blown off course and ended up in New York, and Vice Admiral Samuel Graves, the commander of the fleet in Boston, refused to release ships to transport troops from there to Quebec because the approaching winter would close the Saint Lawrence River.[31] On 25 September 1775 an attempt by Ethan Allen to take Montreal in a surprise attack as the American sympathizer and prominent merchant Thomas Walker had promised he would open the city's gates was foiled.[32] A mixed force of 34 men from the 26th Foot regiment, 120 Canadien volunteers and 80 "Old Subject" volunteers, 20 Indian Department employees and six Indians under the command of Major John Campbell stopped Allen's force on the outskirts of Montreal, killing 5 of the Americans and capturing 36.[32] The victory caused 1, 200 Canadiens to finally respond to the militia summons, but Carleton, knowing only a large American force had entered Canada, chose to stay on the defensive under the grounds he was probably outnumbered.[33] On 5 October, Carleton ordered Walker arrested on charges of high treason, which led to a shoot-out that left two soldiers wounded, Walker's house burned down, and Walker captured.[33] On 15 October 1775, heavy guns arrived from Fort Ticonderoga, which finally allowed the American besiegers to start inflicting damage on Fort St. Jean and on 18 October, the fort at Chambly fell to the Americans.[33]

The attempts of the Americans to recruit Canadiens (French-Canadians) for their cause were generally unsuccessful with Jeremy Duggan, an "Old Subject" Quebec City barber who had joined the Americans only recruiting 40 Canadiens.[34] The Roman Catholic clergy preached loyalty to the Crown, but the unwillingness of Carleton to take the offensive persuaded many Canadiens that the British cause was a lost one.[34] Given the American numerical superiority, Carleton had decided to stay on the defensive, a decision which however justified under military grounds, proved to be politically damaging.[34] On 2 November 1775, Montgomery took Fort St. Jean, which the Americans had been besieging since September, causing Carleton to decide to pull back to Quebec City, which he knew that Arnold was also approaching.[35] On 11 November, the British pulled out of Montreal and on 13 November 1775, the Americans took Montreal.[36] Like Carleton, Montgomery was an Irishman, and both generals had a certain understanding and respect for Canadien society, which was in many ways similar to Irish society, going out of their way to be tactful and polite in their dealings with Canadiens.[37] Montgomery insisted that his men display "brotherly affection" for the Canadiens at all times.[37] However, the man that Montgomery placed in charge of Montreal, Brigadier General David Wooster, together with the newly freed Thomas Walker who served as Wooster's chief political adviser, displayed bigoted anti-Catholic and anti-French views, with Wooster shutting down all the "Mass houses" as he called Catholic churches just before Christmas Eve, a move that deeply offended the Canadiens.[38] The arbitrary and high-handed behavior of Wooster and Walker in Montreal together with their anti-Catholicism undercut their claims to be promoting "liberty" and did much to turn Canadien opinion against their self-proclaimed "liberators".[39]

When definitive word reached Quebec on November 3 that Arnold's march had succeeded and that he was approaching the city, Cramahé began tightening the guard and had all boats removed from the south shore of the Saint Lawrence.[40] Word of Arnold's approach resulted in further militia enlistments, increasing the ranks to 1,200 or more.[30] Two ships arrived on November 3, followed by a third the next day, carrying militia volunteers from St. John's Island and Newfoundland that added about 120 men to the defense. A small convoy under the command of the frigate HMS Lizard also arrived that day, from which a number of marines were added to the town's defenses.[41]

On November 10, Lieutenant Colonel Allen Maclean, who had been involved in an attempt to lift the siege at St. Jean, arrived with 200 men of his Royal Highland Emigrants. They had intercepted communications from Arnold to Montgomery near Trois-Rivières, and hurried to Quebec to help with its defense. The arrival of this experienced force boosted the morale of the town militia, and Maclean immediately took charge of the defenses.[42]

Carleton arrives at Quebec

In the wake of the fall of Fort St. Jean, Carleton abandoned Montreal and returned to Quebec City by ship, narrowly escaping capture.[43] Upon his arrival on November 19, he immediately took command. Three days later, he issued a proclamation that any able-bodied man in the town who did not take up arms would be assumed to be a rebel or a spy, and would be treated as such. Men not taking up arms were given four days to leave.[44] As a result, about 500 inhabitants (including 200 British and 300 Canadians) joined the defense.[45]

Carleton addressed the weak points of the town's defensive fortifications: he had two log barricades and palisades erected along the Saint Lawrence shoreline, within the area covered by his cannons; he assigned his forces to defensive positions along the walls and the inner defenses;[46] and he made sure his inexperienced militia were under strong leadership.[47]

Order of battle

Order of battle of forces during the battle and subsequent campaigns:[48][49][50][51]

British Army

British forces numbered 1,800, commanded by Guy Carleton, with 5 killed and 14 wounded.

- 7th Regiment of Foot (Royal Fusiliers), one company in Montreal and one in Quebec

- 21st (Royal North British) Fusiliers Regiment of Foot

- 24th Regiment of Foot

- 26th Regiment of Foot

- Elements, Royal Highland Emigrants

- Elements, His Majesty's Marine Forces

- Forces not engaged, but in the area:

- 6 companies from 7th Regiment of Foot (Royal Fusiliers)

- 8th (The King's) Regiment of Foot, spread in companies throughout the Frontier forts

American forces

American forces numbered 1,200, commanded by Major General Richard Montgomery, with 50 killed, 34 wounded, and 431 missing/captured. An unknown number of militia were attached.

Arnold's arrival

The British believed that the forbidding landscape of upper Massachusetts (modern Maine) was impassable to a military force, but General Washington felt that the upper Massachusetts could be crossed in about 20 days.[52] Arnold called for 200 bateaux (boats) and for "active woodsmen, well acquainted with bateaux".[52] After recruiting 1,050 volunteers, Arnold departed for Quebec City on 5 September 1775.[52] The men Arnold chose for his expedition were volunteers drawn from New England companies serving in the siege of Boston. They were formed into two battalions for the expedition; a third battalion was composed of riflemen from Pennsylvania and Virginia under Captain Daniel Morgan's command.[53] After landing in Georgetown on 20 September, Arnold began his voyage up the Kennebec river.[52] Arnold thought it was only 180 miles (290 km) to Quebec City, but actually the distance was 300 miles (480 km) and the terrain was far more difficult than he expected.[52]

The trek through the wilderness of Maine was long and difficult with icy rains, dysentery caused by drinking unclean waters, and rivers full of drowned trees all presenting problems.[54] The conditions were wet and cold, and the journey took much longer than either Arnold or Washington had expected. Bad weather and wrecked boats spoiled much of the expedition's food stores, and about 500 men of the original 1,100 turned back or died. Those who turned back, including one of the New England battalions, took many of the remaining provisions with them. The men who continued on were starving by the time they reached the first French settlements in early November.[55] By the time they reached the Chaudière River, Arnold's men were eating their leather shoes and belts, and upon encountering the first habitant settlements on 2 November, they were overjoyed to be offered meals of beef, oatmeal and mutton, though they complained that the Canadiens charged too much for their food.[56] On 3 November, the frigate HMS Lizard arrived in Quebec City with 100 men from Newfoundland.[57] On 8 November, Arnold could see for the first time the walls of Quebec City towering over the St. Lawrence.[57] On November 9, the 600 survivors of Arnold's march from Boston to Quebec arrived at Point Levis, on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River opposite Quebec City. Despite the condition of his troops, Arnold immediately began to gather boats to make a crossing. Arnold was prepared to do so on the night of November 10, but a storm delayed him for three days. An Indian chief greeted Arnold, and agreed to provide him with canoes to cross the St. Lawrence River together with some 50 men to serve as guides.[57] On 12 November, MacLean with his Highlanders arrived in Quebec City.[57] Starting about 9 pm on 13 November, the Americans crossed the St. Lawrence in canoes to land at Wolfe's Cove, and by 4 am, about 500 men had crossed over.[58] Once on the other side of the St. Lawrence, Arnold moved his troops onto the Plains of Abraham, about 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from the city walls.[59]

The troops approaching Quebec's walls were significantly under-equipped. Arnold had no artillery, each of his men carried only five cartridges and the men's clothing had been reduced to rags. Despite being outnumbered two to one, Arnold demanded the city's surrender. Both envoys sent were shot at by British cannons, ("killing the messenger" has historically been viewed as an unusual and very contradictory, if not rogue, breach of war protocol as emissaries were not supposed to be undertaking a suicide march but strictly deliver a message of demands or negotiations and come back to their leaders unmolested, with a reply; either a refusal or counter offer.) Their death clearly signified that the demand had been rebuked.[60] At a council of war called by Cramahé on 16 November, MacLean as the most senior military officer present advocated for holding out.[61] MacLean stated that Quebec City had a garrison of 1,178 men and had enough food and firewood for both the garrison and the civilian population to last all through the winter.[61] Arnold concluded that he could not take the city by force, so he blockaded the city on its west side. An inventory ordered by Arnold revealed that over 100 muskets had been so damaged by exposure to the elements during the trek through the wildness that they were now useless.[61] On November 18, the Americans heard a (false) rumor that the British were planning to attack them with 800 men. At a council of war, they decided that the blockade could not be maintained, and Arnold began to move his men 20 mi (32 km) upriver to Pointe-aux-Trembles ("Aspen Point") to wait for Montgomery, who had just taken Montreal.[60] Henry Dearborn, who later became U.S. Secretary of War under President Thomas Jefferson, was present at the battle and wrote his famous journal, The Quebec Expedition, which outlined the long and difficult march to the battle and the events that occurred there.[62]

Montgomery's arrival

On December 1, Montgomery arrived at Pointe-aux-Trembles. His force consisted of 300 men from the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd New York regiments, a company of artillery raised by John Lamb,[63] about 200 men recruited by James Livingston for the 1st Canadian Regiment, and another 160 men led by Jacob Brown who were remnants of regiments disbanded due to expiring enlistments.[64][65] These were supplemented several days later by a few companies detached by Major General David Wooster, whom Montgomery had left in command at Montreal.[63] The artillery Montgomery brought included four cannons and six mortars, and he also brought winter clothing and other supplies for Arnold's men; the clothing and supplies were a prize taken when most of the British ships fleeing Montreal were captured. Arnold was unpopular with his men, and when Montgomery arrived, several of Arnold's captains asked that they be transferred over serving under Montgomery.[66]

The commanders quickly turned towards Quebec, and put the city under siege on December 6.[64] Montgomery sent a personal letter to Carleton demanding the city's surrender, employing a woman as the messenger.[66] Carleton declined the request and burned the letter unread. Montgomery tried again ten days later, with the same result.[64] The besiegers continued to send messages, primarily intended for the populace in the city, describing the situation there as hopeless, and suggesting that conditions would improve if they rose to assist the Americans.[67] Carleton gave the command of his British Army soldiers, the marines and the Royal Highlanders to MacLean; the sailors to Captain John Hamilton of the Royal Navy; the English-speaking militiamen to Henry Caldwell and the Canadien militiamen to Noël Voyer.[66] While the British began to fortify the Lower Town of Quebec City, Montgomery used his five mortars to begin bombarding Quebec City while American riflemen were assigned as snipers to gun down the soldiers patrolling the walls of Quebec City.[66] Many of the enlistments of Montgomery's force expired on 31 December 1775, and despite his efforts to persuade his men to stay on, it was made clear by the Continental Army soldiers that they intended to go home once their enlistments ended.[68] As December advanced, Montgomery was under increasing pressure to take Quebec City before 31 December.[68]

On December 10, the Americans set up their largest battery of artillery 700 yd (640 m) from the walls. The frozen ground prevented the Americans from entrenching the artillery, so they fashioned a wall out of snow blocks.[64] This battery was used to fire on the city, but the damage it did was of little consequence. Montgomery realized he was in a very difficult position, because the frozen ground prevented the digging of trenches, and his lack of heavy weapons made it impossible to breach the city's defenses. On 17 December, British cannons knocked out two of Montgomery's mortars, leading him to order the remaining three back.[68] The enlistments of Arnold's men were expiring at the end of the year, and no ammunition was on the way from the colonies. Furthermore, it was very likely that British reinforcements would arrive in the spring, meaning he would either have to act or withdraw. Montgomery believed his only chance to take the city was during a snowstorm at night, when his men could scale the walls undetected.[69] On Christmas Day, Montgomery announced in speech before his army his plans to take Quebec City.[68]

While Montgomery planned the attack on the city, Christophe Pélissier, a Frenchman living near Trois-Rivières, came to see him. Pélissier was a political supporter of the American cause who operated the St. Maurice Ironworks.[70] He and Montgomery discussed the idea of holding a provincial convention to elect representatives to Congress. Pélissier recommended against this until after Quebec City had been taken, as the habitants would not feel free to act in that way until their security was better assured.[71] The two agreed that Pélissier's ironworks would provide munitions (ammunition, cannonballs, and the like) for the siege. This, Pélissier did until the Americans retreated in May 1776, at which time he also fled with them, His ironworks supplied ammunition, bombs, and cannonballs for the siege of Quebec; he also wrote a letter to the Second Continental Congress on January 8, 1776, to point out the measures they should take for a successful taking of Quebec. As the Americans retreated from Quebec in May and June 1776, Pélissier fled the province with them. On July 29, 1776, he received an engineering lieutenant colonel's commission in the Continental Army, and in October assisted in the improvement of the defenses at Fort Ticonderoga. He eventually returned to his family home in France.[72]

A snowstorm arrived on the night of December 27, prompting Montgomery to prepare the troops for the attack. However, the storm subsided, and Montgomery called off the assault. That night, a sergeant from Rhode Island deserted, carrying the plan of attack to the British. Montgomery consequently drafted a new plan; this one called for two feints against Quebec's western walls, to be led by Jacob Brown and James Livingston,[73] while two attacks would be mounted against the lower town.[69] Arnold would lead one attack to smash through the defenses at the north end of the Lower town through the Sault au Matelot and Montgomery would follow along the Saint Lawrence south of the Lower Town.[68] The two forces would meet in the lower town and then launch a combined assault on the upper town by scaling its walls, believing that the "Old Subject" merchants living in the Upper Town would force Carleton to surrender upon the Upper Town was entered.[68] Much of the hope behind Montgomery's plan was their either the "Old Subject" merchants would force Carleton to surrender once the Americans entered the city and/or the threat of having the warehouses destroyed would lead to the city's merchants likewise compelling Carleton to surrender.[12] The new plan was revealed only to the senior officers.[46] On the afternoon of 30 December 1775, a "nor'easter" came from the Atlantic, bringing in a heavy snowfall, and Montgomery knowing that much of his army would be leaving in two days' time, ordered his men to form up for an assault on Quebec City.[68]

Battle

Montgomery's attack

A storm broke out on December 30, and Montgomery once again gave orders for the attack. Brown and Livingston led their militia companies to their assigned positions that night: Brown by the Cape Diamond redoubt, and Livingston outside St. John's Gate (fr). When Brown reached his position between 4 am and 5 am, he fired flares to signal the other forces, and his men and Livingston's began to fire on their respective targets.[74] Montgomery and Arnold, seeing the flares, set off for the lower town.[46]

Montgomery led his men from Wolfe's Cove down the steep, snow-heaped path towards the outer defenses.[68] The storm had turned into a blizzard, making the advance a struggle. As they advanced over the ice-covered rocky ground, the bells of the Notre-Dame-des-Victoires church began to ring, signaling the militiamen to arm themselves, as sentries manning the walls of Quebec City saw the American lanterns in the blizzard.[75] Montgomery's men eventually arrived at the palisade of the outer defenses, where an advance party of carpenters sawed their way through the wall. Montgomery himself helped saw through the second palisade, and led 50 men down a street towards a two-story building. The building formed part of the city's defenses, and was in fact a blockhouse occupied by 39 Quebec militia and 9 sailors armed with muskets and cannons.[76]

Montgomery unsheathed his sword as he led his men down the street as the blizzard raged.[76] The defenders opened fire at close range, and Montgomery was killed instantly, shot through the head by a burst of grapeshot while most of the men standing beside him were either killed or wounded.[76] The few men of the advance party who survived fled back towards the palisade; only Aaron Burr and a few others escaped unhurt.[77] As the next two most senior officers, John Macpherson and Jacob Cheesemen, were also killed, command was assumed by the deputy quartermaster, Colonel Donald Campbell, who decided it was suicidal to try to advance again.[76] Many of Montgomery's officers were injured in the attack; one of the few remaining uninjured officers led the survivors back to the Plains of Abraham, leaving Montgomery's body behind.[78]

Arnold's attack

While Montgomery was making his advance, Arnold advanced with his main body towards the barricades of the Sault-au-Matelot at the northern end of the lower town.[79] Leading Arnold's advance were 30 riflemen together with the artillerymen who attached a brass 6-pounder cannon to a sled.[76] Behind them were the rest of the riflemen from Virginia and Pennsylvania, then the Continental Army volunteers from New England, and finally the rearguard consisted of those Canadiens and Indians from the Seven Nations of Canada who had decided to join the Americans.[76]

They passed the outer gates and some British gun batteries undetected. However, as the advance party moved around the Porte du Palais (Palace Gate) (fr), heavy fire broke out from the city walls above them.[80] The defenders opened fire with their muskets and hurled grenades down from the walls.[76] The sled carrying the cannon was struck in a snowdrift in an attempt to avoid the hostile fire and was abandoned.[76] The height of the walls made it impossible to return the defenders' fire, therefore Arnold ordered his men to run forward to the docks of Quebec City that were not behind the walls.[76] In the process, the Americans became lost amid the unfamiliar streets of Quebec City and the raging blizzard.[12]

They advanced down a narrow street, where they once again came under fire as they approached a barricade manned by 30 Canadien militiamen armed with three light cannons.[76] Arnold had planned to use the cannon he brought with him, but since the gun was lost, he had no choice but to order a frontal attack.[76] As he was organizing his men in an attempt to take the barricade, Arnold received a deep wound in the leg from a musket ball that apparently ricocheted,[81] and was carried to the rear after transferring command of his detachment to Daniel Morgan.[82] Morgan, a tough Virginia frontiersman well respected by his men, personally led the assault, scaling a ladder up the barricade and was knocked down on his first attempt.[76] On his second attempt, Morgan made to the top of the barricade, had to roll under one of the cannons to escape the bayonets of the defenders, but the rest of his men followed up.[76] After a few minutes of fighting, the 30 militiamen surrendered while the Americans had lost 1 dead and six wounded.[76]

Under Morgan's command, they captured the barricade, but had difficulty advancing further because of the narrow twisting streets and damp gunpowder, which prevented their muskets from firing. Moreover, despite Morgan's exhortations to advance, his men were afraid of being overpowered by their prisoners and wanted to wait for the rest of the Continental Army force to come up, leading to a 30-minute delay.[83] Morgan and his men holed up in some buildings to dry out their powder and rearm, but they eventually came under increasing fire; Carleton had realized the attacks on the northern gates were feints and began concentrating his forces in the lower town.

Caldwell was speaking with Carleton when he learned of the assault on the Porte du Palais, and took with him 30 Royal Highland Emigrants and 50 sailors as he headed out to stop the assault.[84] At the second barricade, he found some 200 Canadien militiamen under Voyer and a company from the 7th Foot Regiment, who were confused about what was going on, whom he gave his orders to.[84] Caldwell ordered the Royal Highlanders and the militia into the houses while ordering the 7th Foot to form a double line behind 12-foot high barricade.[84] As Morgan and his men advanced down the narrow streets of Quebec City, they were confronted by the sailors led by a man named Anderson who demanded their surrender.[84] Morgan in reply shot Anderson dead while his sailors retreated; shouting "Quebec is ours!", Morgan then led a charge down the street.[84] The Royal Highlanders and the militia opened fire from the windows in the houses.[84] Despite the storm of bullets raining down on them, the Americans were able to place ladders against the barricades, but their attempts to scale it were all beaten back.[84] An attempt to outflank the barricade by going through one of the houses led to a savage fight in the house with bayonet against bayonet, but was also repulsed.[84] Under increasing heavy fire, Morgan ordered his men into the houses.[84]

A British force of 500 sallied from the Palace Gate and reoccupied the first barricade, trapping Morgan and his men in the city.[85] Captain George Laws led his 500 men, consisting of Royal Highlanders and sailors out of the Palace Gate, when they encountered an American force under Henry Dearborn who was coming up to aid Morgan.[84] As Dearborn's men had their powder damp, they could not use their muskets and Dearborn and the rest of his men surrendered.[84] Laws then turned against Morgan's group, who proved to be more stubborn.[84] Laws himself was captured, but the attempts of the Americans to break out were blocked.[84] As the fighting continued, the Americans ran out of ammunition and one by one, groups of Continental Army soldiers gave up the fight.[84] With no avenue of retreat and under heavy fire, Morgan and his men surrendered. The battle was over by 10 am.[86] Morgan was the last to surrender and rather than give up his sword to a British officer, he handed it to a Catholic priest who had been sent under a flag of truce to ask for his surrender.[84] Finally, Carleton ordered an assault on the battery outside the walls, which was captured, and afterwards the British withdrew back behind the safety of the walls.[84] Found on the American corpses in the snow were paper streamers attached to their hats reading "Liberty or Death!".[12]

This was the first defeat suffered by the Continental Army. Carleton reported 30 Americans killed and 431 taken prisoner, including about two-thirds of Arnold's force. He also wrote that "many perished on the River" attempting to get away.[6] Allan Maclean reported that 20 bodies were recovered in the spring thaw the following May. Arnold reported about 400 missing or captured, and his official report to Congress claimed 60 killed and 300 captured.[6] British casualties were comparatively light. Carleton's initial report to General William Howe mentioned only five killed or wounded, but other witness reports ranged as high as 50.[87] Carleton's official report listed five killed and 14 wounded.[4]

General Montgomery's body was recovered by the British on New Year's Day 1776 and was given a simple military funeral on January 4, paid for by Lieutenant Governor Cramahé. The body was returned to New York in 1818.[88] Together with the losses taken in the battle and the expiring enlistments left Arnold with only 600 men as 1 January 1776 to besiege Quebec City.[89] Arnold asked for David Wooster, commanding the Continental Army force in Montreal to send him some of his men, but Wooster refused, saying he was afraid of a pro-British uprising if he were to send away any of his forces.[89] An appeal to help for Schuyler led to the reply that he could spare no men as the problem of expiring enlistments led him short of men, and moreover, Guy Johnson had succeeded in persuading some of the Mohawk to fight for the Crown.[89] General Washington complained that the refusal of Congress to offer long-term enlistments or even bounties to those whose enlistments were about to expire was threatening to hobble the rebellion, and led him to consider resigning.[89]

Siege of the fortress

Arnold refused to retreat; despite being outnumbered three to one, the sub-freezing temperature of the winter and the mass departure of his men after their enlistments expired, he laid siege to Quebec. The siege had relatively little effect on the city, which Carleton claimed had enough supplies stockpiled to last until May.[90] Immediately after the battle, Arnold sent Moses Hazen and Edward Antill to Montreal, where they informed General Wooster of the defeat. They then travelled on to Philadelphia to report the defeat to Congress and request support. (Both Hazen and Antill, English-speakers originally from the Thirteen Colonies who had settled in Quebec, went on to serve in the Continental Army for the rest of the war.)[91] In response to their report, Congress ordered reinforcements to be raised and sent north. During the winter months, small companies of men from hastily recruited regiments in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut made their way north to supplement the Continental garrisons at Quebec and Montreal.[92] The journey to Quebec City in the winter left the reinforcements in poor health and many of their weapons unserviceable.[93] Arnold used his remaining artillery to shell Quebec City, which caused some damage, but did little did to weaken Carleton's hold as Arnold only destroyed the homes of civilians.[94] Carleton continued to build new blockhouses and trenches over the course of the winter and cut a trench in the frozen St. Lawrence to prevent an attempt to outflank the walls of Quebec City.[95]

The presence of disease in the camp outside Quebec, especially smallpox, took a significant toll on the besiegers, as did a general lack of provisions.[96] Smallpox ravaged Montgomery and Arnold's forces largely due to exposure to infected civilians released from Quebec. Governor Carleton condoned this practice, realizing it would severely weaken the American siege effort.[97] Carleton is reported to have sent out several prostitutes infected with smallpox who in turn passed it on to the Continental Army.[93] Arnold after using up all his gold could only pay for supplies with paper money, not coin, which proved to be problematic as the habitants wanted coins, and increasingly the Americans had to take supplies at bayonet point.[93] Together with the news of the anti-Catholic policies carried out by Wooster in Montreal, the requisitions of food and firewood made the besiegers more and more unpopular with the habitants who wanted the Americans to go home.[94] In early April, Arnold was replaced by General Wooster, who was himself replaced in late April by General John Thomas.[98]

Governor Carleton, despite appearing to have a significant advantage in manpower, chose not to attack the American camp, and remained within Quebec's walls. Montgomery, in analysing the situation before the battle, had observed that Carleton served under James Wolfe during the 1759 siege of Quebec, and knew that the French General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm had paid a heavy price for leaving the city's defenses, ultimately losing the city and his life in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. British General James Murray had also lost a battle outside the city in 1760; Montgomery judged that Carleton was unlikely to repeat their mistakes.[99] On March 14, Jean-Baptiste Chasseur, a miller from the southern shore of the Saint Lawrence, reached Quebec City and informed Carleton there were 200 men on the south side of the river ready to act against the Americans.[100] These men and more were mobilized to make an attack on an American gun battery at Point Levis, but an advance guard of this Loyalist militia was defeated in the March 1776 Battle of Saint-Pierre by a detachment of pro-American local militia. under Major Lewis Dubois[101] On 2 April 1776, a new battery built by the Americans at Point Lévis started to shell Quebec City and ships in the St. Lawrence as the river thawed in the spring.[93]

To rally support in Quebec, Congress sent a three-man commission consisting of Charles Carroll, Samuel Chase and Benjamin Franklin together with a pro-Patriot Catholic priest, Father John Carroll, and Fleury Mesplet, a French printer living in Philadelphia.[38] On 29 April 1776, the commission arrived in Montreal and attempted to undo the damage done by Wooster, but found that public opinion had turned against them.[102] Several Canadien leaders pointedly asked the commissioners that if the rebellion was justified because of "no taxation without representation", then why had Wooster imposed taxes on them in the name of Congress without their representation in Congress.[39] Father Carroll talked extensively with his fellow Catholic priests in Quebec in a bid to win their support, but reported that the majority were satisfied with the Quebec Act, and were unwilling to support the rebellion.[102] Though the Congressional commissioners rescinded Wooster's anti-Catholic decisions and allowed Catholic churches to re-open, by then the political damage could not be repaired.[102]

When General Thomas arrived, the conditions in the camp led him to conclude that the siege was impossible to maintain, and he began preparing to retreat. On 3 May, the Americans sent a fireship down the St. Lawrence in an attempt to burn down the Queen's Wharf, but British artillery sank the fireship.[95] The arrival on May 6 of a small British fleet carrying 200 regulars (the vanguard of a much larger invasion force), accelerated the American preparations to depart. Arriving in Quebec City were the frigates HMS Surprise and HMS Isis carrying the 29th Foot Regiment as well as marines.[95] The retreat was turned into a near rout when Carleton marched these fresh forces, along with most of his existing garrison, out of the city to face the disorganized Americans.[103] The American forces, ravaged by smallpox (which claimed General Thomas during the retreat), eventually retreated all the way back to Fort Ticonderoga.[104] Carleton then launched a counteroffensive to regain the forts on Lake Champlain. Although he defeated the American fleet in the Battle of Valcour Island and regained control of the lake, the rear guard defense managed by Benedict Arnold prevented further action to capture Ticonderoga or Crown Point in 1776.[105]

Aftermath

On May 22, even before the Americans had been completely driven from the province, Carleton ordered a survey to identify the Canadians who had helped the American expedition in and around Quebec City. François Baby, Gabriel-Elzéar Taschereau, and Jenkin Williams travelled the province and counted the Canadians who actively provided such help; they determined that 757 had done so.[91] Carleton was somewhat lenient with minor offenders, and even freed a number of more serious offenders on the promise of good behaviour. However, once the Americans had been driven from the province, measures against supporters of the American cause became harsher, with a frequent punishment being forced labour to repair infrastructure destroyed by the Americans during their retreat.[106] These measures had the effect of minimizing the public expression of support for the Americans for the rest of the war.[107] Still, some Canadiens continued to fight for the Revolution as the Continental Army retreated from Quebec. Under Hazen and Livingston, several hundred men remained in the ranks and, now deprived of their property and means along the St. Lawrence, relied on army pay and the promise of a pension from Congress to survive. Some obtained land grants in northern New York at war's end.[108]

Between May 6 and June 1, 1776, nearly 40 British ships arrived at Quebec City.[109] They carried more than 9,000 soldiers under the command of General John Burgoyne, including about 4,000 German auxiliaries from Brunswick and Hesse-Hanau (so-called Hessians) under the command of Baron Friedrich Adolf Riedesel.[110] These forces, some of which having participated in Carleton's counteroffensive, spent the winter of 1776–77 in the province, putting a significant strain on the population, which numbered only about 80,000.[111] Carleton told the habitants that the quartering of the British and Brunswick troops was punishment for their "disloyalty" in not coming out in greater numbers when he summoned the militia.[112] The Canadian historian Desmond Morton described Carleton as having "wisely" avoided battle outside of Quebec City in 1775–76, but overall his command in the campaign of 1775–76 was "lack-lustre", which led to John Burgoyne being given command of the invasion of New York in 1777.[112] Many of these troops were deployed in 1777 for Burgoyne's campaign for the Hudson Valley.[113]

Following the American victory at the battle of Saratoga, Congress once again considered invading Canada and in January 1778 voted for another invasion to be commanded by the Marquis de La Fayette.[114] However, La Fayette found the necessary supplies and horses to support an invasion were lacking once he reached Albany and he advised cancelling the operation, advice that Congress accepted in March 1778.[114] The news that the British had strengthened the forts on the border together with the walls of Montreal and of Quebec City meant that an invasion of Canada would require a substantial number of men and resources that were not available owing to operations elsewhere.[114] Quebec City's status as one of the strongest fortified cities in North America meant it would require a massive amount of force to take. The idea of invading Canada continued to be debated in Congress up to 1780, but no decision was ever made. During the peace negotiations in Paris in 1782–83 for ending the American Revolutionary War, the American delegation asked for the cession of Canada (at the time, the term Canada applied only to what is now southern Quebec and southern Ontario) to the United States.[13] As the Americans did not have possession of Canada at the time, the British refused and the American diplomats did not press the point.[13] Had the Americans been victorious at the battle of Quebec, and were still in possession of Canada at the time of the peace negotiations, the American diplomats in Paris might have been more successful in demanding what is now southern Ontario and southern Quebec become part of the United States.

Three current United States Army National Guard units (Company A of the 69th Infantry Regiment,[115] the 181st Infantry Regiment,[116] and the 182nd Infantry[117]) trace their lineage to American units that participated in the Battle of Quebec.

See also

- List of American Revolutionary War battles

- American Revolutionary War §Early Engagements. The Battle of Quebec placed in sequence and strategic context.

Notes

- ↑ Davies, Blodwen (1951). Quebec: Portrait of a Province. Greenberg. p. 32.Carleton's men had won a quick and decisive victory

- ↑ Smith (1907), vol 2, p. 98. On p. 94, Carleton reports to Dartmouth on November 20 that 1,186 are ready. This number is raised by Smith to 1,800 due to increased militia enrollment after that date.

- ↑ Smith (1907), vol 2, p. 86 lists "less than 200" for Livingston's 1st Canadian Regiment, and 160 for Brown. Griffin (1907), p. 114 says that Livingston brought 300 militia. Nelson (2006), p. 133 counts Arnold's troops at "550 effectives"; Smith (1907), vol 2, p. 12 counts Arnold's troops at 675.

- 1 2 3 Gabriel (2002) p. 170

- ↑ Boatner, p. 908

- 1 2 3 Smith (1907), vol 2, p. 581

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), pp. 44–45

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), p. 22

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), pp. 22–23

- 1 2 3 Morrissey (2003), p. 23

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Morrissey (2003), p. 15

- 1 2 3 4 Morton (1999), p. 44

- 1 2 3 Morrissey (2003), p. 89

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), p. 13

- 1 2 3 Morrissey (2003), p. 30

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), pp. 47–49, 63

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), p. 97

- 1 2 3 Morrissey (2003), p. 33

- ↑ Smith (1907), vol 1, p. 326

- ↑ Stanley (1973), pp. 37–80

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), pp. 13–15

- ↑ Morton (1999), p. 43

- ↑ Black (2009), pp. 52–53

- 1 2 Morrissey (2003), p. 31

- ↑ Stanley (1973), pp. 21–36

- 1 2 Morrissey (2003), p. 24

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), p. 18

- 1 2 Morrissey (2003), p. 32

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), pp. 23, 32

- 1 2 Smith (1907) vol 2, pp. 10–12

- ↑ Smith (1907) vol 2, pp. 14–15

- 1 2 Morrissey (2003), p. 40

- 1 2 3 Morrissey (2003), p. 41

- 1 2 3 Morrissey (2003), p. 37

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), p. 44–45

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), p. 44

- 1 2 Morrissey (2003), p. 64–65

- 1 2 Morrissey (2003), p. 65

- 1 2 Morrissey (2003), p. 65–66

- ↑ Smith (1907) vol 2, pp. 9–10

- ↑ Smith (1907) vol 2, p. 16

- ↑ Smith (1907) vol 2, p. 21

- ↑ Smith (1907) vol 1, pp. 487–490

- ↑ Smith (1907) vol 2, p. 95

- ↑ Shelton (1996), p. 130

- 1 2 3 Wood (2003), p. 49

- ↑ Smith (1907) vol 2, pp. 97–98

- ↑ "The Invasion of Canada and the Siege of Quebec". December 25, 2007. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ↑ "Battle of Quebec 1775". www.britishbattles.com. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ↑ "American War of Independence, 1775–1783". December 14, 2007. Archived from the original on December 14, 2007. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ↑ "Battle of Quebec Facts & Summary". American Battlefield Trust. September 27, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Morrissey (2003), p. 46

- ↑ "An Account of the Assault on Quebec, 1775". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania. 14 (4): 434–439. January 1891. JSTOR 20083396.

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), p. 47

- ↑ Nelson (2006), pp. 76–132

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), pp. 49–51

- 1 2 3 4 Morrissey (2003), p. 51

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), pp. 51–52

- ↑ Wood (2003)), p. 44

- 1 2 Wood (2003), p. 46

- 1 2 3 Morrissey (2003), p. 52

- ↑ Dearborn; Peckham (2009). Revolutionary War Journals of Henry Dearborn, 1775–1783

- 1 2 Gabriel, p. 143

- 1 2 3 4 Wood (2003), p. 47

- ↑ Smith (1907), vol 2, p. 86

- 1 2 3 4 Morrissey (2003), p. 53

- ↑ Smith (1907) vol 2, pp. 100–101

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Morrissey (2003), p. 56

- 1 2 Wood (2003), p. 48

- ↑ Fortier

- ↑ Gabriel (2002), pp. 185–186

- ↑ Royal Society of Canada (1887), pp. 85–86

- ↑ United States Continental Congress (1907), p. 82

- ↑ Gabriel (2002), p. 163

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), pp. 56–57

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Morrissey (2003), p. 57

- ↑ Wood (2003), p. 50

- ↑ Gabriel (2002), p. 167

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), p. 106

- ↑ Smith (1907), vol 2, p. 130

- ↑ Senter, Isaac. "The Journal of Isaac Senter, Physician and Surgeon to the Troops Detached From the American Army Encamped at Cambridge, Mass., On a Secret Expedition Against Quebec, Under the Command of Col. Benedict Arnold, in September, 1775"

- ↑ Wood (2003), p. 51

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), pp. 57, 61

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Morrissey (2003), p. 61

- ↑ Smith (1907), vol 2, p. 145

- ↑ Gabriel (2002), p. 164

- ↑ Smith (1907), vol 2, p. 582

- ↑ Sutherland

- 1 2 3 4 Morrissey (2003), p. 62

- ↑ Stanley (1973), p. 86

- 1 2 Lacoursière (1995), p. 433

- ↑ Morrissey (2003), p. 25

- 1 2 3 4 Morrissey (2003), p. 63

- 1 2 Morrissey (2003), pp. 63–64

- 1 2 3 Morrissey (2003), p. 64

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), p. 126

- ↑ Ann M. Becker, "Smallpox in Washington's Army: Strategic Implications of the Disease During the American Revolutionary War," Journal of Military History, Vol. 68, No. 2 (April 2004):408

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), pp. 136–142

- ↑ Smith (1907), vol 2, pp. 248–249

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), p. 130

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), pp. 131–132

- 1 2 3 Morrissey (2003), p. 66

- ↑ Fraser (1907), p. 100. Letter from Carleton to Germain dated May 14, 1776

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), pp. 141–146

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), pp. 162–163

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), p. 151

- ↑ Lacoursière (1995), p. 429

- ↑ Lacroix, Patrick (2019). "Promises to Keep: French Canadians as Revolutionaries and Refugees, 1775–1800". Journal of Early American History. 9 (1): 59–82. doi:10.1163/18770703-00901004. S2CID 159066318.

- ↑ Nelson (2006), p. 212

- ↑ Stanley (1973), pp. 108, 125, 129, 145

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), pp. 31,144,154,155

- 1 2 Morton (1999), p. 45

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), pp. 164–165

- 1 2 3 Morrissey (2003), p. 88–89

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 69th Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981, pp. 328–329.

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 181st Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981, pp. 354–355.

- ↑ Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 182nd Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981, pp. 355–357.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Mark R. (2013). The Battle for the Fourteenth Colony: America's War of Liberation in Canada, 1774–1776. University Press of New England. ISBN 978-1-61168-497-1.

- Boatner, Mark Mayo (1973). Cassell's Biographical Dictionary of the American War of Independence 1763–1783. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-29296-6.

- Black, Jeremy (2009). "The Three Sieges of Quebec". History Today. History Today Ltd (June 2009): 50–55.

- Chidsey, Donald Barr. The war in the North; an informal history of the American Revolution in and near Canada (1967) online

- Desjardin, Thomas A. Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775 (Macmillan, 2007) online.

- Ellison, Amy Noel. "Montgomery’s Misfortune: The American Defeat at Quebec and the March toward Independence, 1775–1776." Early American Studies 15.3 (2017): 591–616. online

- Fortier, M.-F (1979). "Pélissier, Christophe". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- Fraser, Alexander (1907). Fourth Report of the Bureau of Archives, 1906. Toronto: Ontario Bureau of Archives, Dept. of Public Records and Archives. OCLC 1773270.

- Gabriel, Michael P (2002). Major General Richard Montgomery: The Making of an American Hero. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3931-3. OCLC 48163369.

- Griffin, Martin Ignatius Joseph (1907). Catholics and the American Revolution, Volume 1. Ridley Park, Pennsylvania: Self-published. OCLC 648369.

- Lacroix, Patrick (2019). "Promises to Keep: French Canadians as Revolutionaries and Refugees, 1775–1800". Journal of Early American History. 9 (1): 59–82. doi:10.1163/18770703-00901004. S2CID 159066318.

- Lanctot, Gustave (1967). Canada and the American Revolution 1774–1783. Translated by Margaret M. Cameron. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. OCLC 70781264.

- Morrissey, Brendan (2003). Quebec 1775: The American Invasion of Canada. Illustrated by Adam Hook. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-681-2.

- Morton, Desmond (1999). A Military History of Canada. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 0-7710-6514-0.

- Nelson, James L (2006). Benedict Arnold's Navy. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-146806-0. OCLC 255396879.

- Royal Society of Canada (1887). Proceedings and Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, 1886, Series 1, Volume 4. Ottawa: Royal Society of Canada. OCLC 1764607.

- Sawicki, James A. (1981). Infantry Regiments of the US Army. Dumfries, VA: Wyvern Publications. ISBN 978-0-9602404-3-2.

- Shelton, Hal T. (1996). General Richard Montgomery and the American Revolution: From Redcoat to Rebel. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-8039-8. OCLC 77355089.

- Smith, Justin H (1907). Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony, Volumes 1 and 2. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 259236. online

- Stanley, George (1973). Canada Invaded 1775–1776. Toronto: Hakkert. ISBN 978-0-88866-578-2. OCLC 4807930.

- Sutherland, Stuart R.J. (1979). "Montgomery, Richard". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- United States Continental Congress; et al. (1906). Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, Volume 4. Washington, DC: United States Government. OCLC 261514.

- Wood, W. J; Eisenhower, John S D (2003). Battles of the Revolutionary War: 1775–1781. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81329-0. OCLC 56388425.

- Ward, Christopher; Alden, John Richard (1952). The War of the Revolution. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 425995.

- Wrong, George. Canada and the American Revolution; the disruption of the first British empire online

In French

- Lacoursière, Jacques (1995). L'Histoire Populaire du Québec (in French). Sillery, Quebec: Les éditions du Septentrion. ISBN 2-89448-050-4. OCLC 316290514.

- Lacoursière, Jacques (2001). Canada, Québec (in French). Sillery, Quebec: Les éditions du Septentrion. ISBN 2-89448-186-1. OCLC 63083822.

- Starowicz, Mark (2000). Le Canada une histoire populaire (in French). Saint-Laurent, Quebec: Éditions Fides. ISBN 2-7621-2282-1. OCLC 44713313.

External links

- "Battle of Quebec 1775"

- "Battle of Quebec – letters for the years 1775 thru 1776". Familytales.org. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- "Animated History Map of the Invasion of Canada". HistoryAnimated.com. Archived from the original on October 8, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- "Battle of Quebec (1775)". History.com.

- "Battle of Quebec – The 7 Year Project". Sevenyearproject.com.

![]() Media related to Battle of Quebec (1775) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Quebec (1775) at Wikimedia Commons