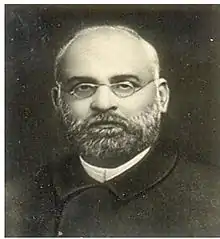

Shyamji Krishna Varma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 4 October 1857 |

| Died | 30 March 1930 (aged 72) |

| Monuments | Kranti Teerth, Mandvi, Kutch |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford |

| Occupation(s) | Revolutionary, lawyer, journalist |

| Organizations | |

| Movement | Indian Independence Movement |

| Spouse |

Bhanumati (m. 1875) |

| Parent(s) | Karsan Bhanushali (Nakhua), Gomatibai |

Shyamji Krishna Varma (4 October 1857 – 30 March 1930) was an Indian revolutionary fighter,[1] an Indian patriot, lawyer and journalist who founded the Indian Home Rule Society, India House and The Indian Sociologist in London. A graduate of Balliol College, Krishna Varma was a noted scholar in Sanskrit and other Indian languages. He pursued a brief legal career in India and served as the Divan of a number of Indian princely states in India.[2] He had, however, differences with Crown authority, was dismissed following a supposed conspiracy of British colonial officials at Junagadh[3] and chose to return to England. An admirer of Dayanand Saraswati's approach of cultural nationalism, and of Herbert Spencer, Krishna Varma believed in Spencer's dictum: "Resistance to aggression is not simply justified, but imperative".[2]

In 1905, he founded the India House and The Indian Sociologist, which rapidly developed as an organised meeting point for radical nationalists among Indian students in Britain at the time and one of the most prominent centres for revolutionary Indian nationalism outside India. Krishna Varma moved to Paris in 1907, avoiding prosecution.

Early life

Shyamji Krishna Varma was born on 4 October 1857 in Mandvi, Cutch State (now Kutch, Gujarat) as Shamji, the son of Krushnadas Bhanushali (Karsan Nakhua; Nakhua is the surname while Bhanushali is the community name), a labourer for cotton press company, and Gomatibai, who died when Shyamji was only 11 years old. He was raised by his grandmother. His ancestors came from Bhachunda (23°12'3"N 69°0'4"E), a village now in Abdasa taluka of Kutch district. They had migrated to Mandvi in search of employment and due to familial disputes. After completing secondary education in Bhuj, he went to Mumbai for further education at Wilson High School. Whilst in Mumbai, he learned Sanskrit.[4]

In 1875, he married Bhanumati, a daughter of a wealthy businessman of the Bhatia community and sister of his school friend Ramdas. Then he got in touch with the nationalist Swami Dayananda Saraswati, a reformer and an exponent of the Vedas, who had founded the Arya Samaj. He became his disciple and was soon conducting lectures on Vedic philosophy and religion.

In 1877, a public speaking tour secured him a great public recognition. He became the first non-Brahmin to receive the prestigious title of Pandit by the Pandits of Kashi in 1877.

He came to the attention of Monier Williams, an Oxford professor of Sanskrit who offered Shyamji a job as his assistant.[4]

Oxford

Shyamji arrived in England and joined Balliol College, Oxford on 25 April 1879 with the recommendation of Professor Monier Williams. Passing his B.A. in 1883, he presented a lecture on "the origin of writing in India" to the Royal Asiatic Society. The speech was very well received and he was elected a non-resident member of the society. In 1881, he represented India at the Berlin Congress of Orientalists.

Legal career

He returned to India in 1885 and started practice as a lawyer. Then he was appointed as Diwan (chief minister) by the King of Ratlam State; but ill health forced him to retire from this post with a lump sum gratuity of RS 32052 for his service. After a short stay in Mumbai, he settled in Ajmer, headquarters of his Guru Swami Dayananda Saraswati, and continued his practice at the British Court in Ajmer.

He invested his income in three cotton presses and secured sufficient permanent income to be independent for the rest of his life. He served for the Maharaja of Udaipur as a council member from 1893 to 1895, followed by the position of Diwan of Junagadh State. He resigned in 1897 after a bitter experience with a British agent that shook his faith in British rule in India.

Nationalism

Having read Satyarth Prakash and other books of Swami Dayanand Saraswati, Shyamji Krishna Varma was very much impressed with his philosophy, writings and spirit of Nationalism and had become one of his ardent admirers. It was upon Dayanand's inspiration, he set up a base in England at India House.

However, he rejected the petitioning, praying, protesting, cooperating and collaborating policy of the Congress Party, which he considered undignified and shameful. Shyamji Krisha supported Lokmanya Tilak during the Age of Consent bill controversy of 1890. In 1897, following the harsh measures adopted by the British colonial government during the plague crisis in Poona, he supported the assassination of the Commissioner of Plague by the Chapekar brothers but he soon decided to fight inside Britain for Indian independence.

England

Ordained by Swami Dayanand Saraswati, the founder of Arya samaj, Shyamji Krishan Varma upon his arrival in London stayed at the Inner Temple and studied Herbert Spencer's writings in his spare time. In 1900, he bought an expensive house in Highgate.

He was inspired by Spencer's writings. At Spencer's funeral in 1903, he announced the donation of £1,000 to establish a lectureship at University of Oxford in tribute to him and his work.

A year later he announced that Herbert Spencer Indian fellowships of RS 2000 each were to be awarded to enable Indian graduates to finish their education in England. He announced additional fellowship in memory of the late Dayananda Saraswati, the founder of Arya Samaj, along with another four fellowships in the future.

Political activism

In 1905, Shyamji focused his activity as a political propagandist and organiser for the complete independence of India. Shyamji made his debut in Indian politics by publishing the first issue of his English monthly, The Indian Sociologist, an organ and of political, social and religious reform. This was an assertive, ideological monthly aimed at inspiring mass opposition to British rule, which stimulated many intellectuals to fight for the independence of India.

Indian Home Rule Society

On 18 February 1905, Shyamji inaugurated a new organisation called The Indian Home Rule Society. The first meeting, held at his Highgate home, unanimously decided to found The Indian Home Rule Society with the object of:

- Securing Home Rule for India

- Carrying on propaganda in England by all practical means with a view to attain the same.

- Spreading among the people of India the objectives of freedom and national unity.

India House

As many Indian students faced racist attitudes when seeking accommodations, he founded India House as a hostel for Indian students, based at 65, Cromwell Avenue, Highgate. This living accommodation for 25 students was formally inaugurated on 1 July by Henry Hyndman, of the Social Democratic Federation, in the presence of Dadabhai Naoroji, Lala Lajpat Rai, Madam Cama, Mr. Swinney (of the London Positivist Society), Mr. Harry Quelch (the editor of the Social Democratic Federation's Justice) and Charlotte Despard, the Irish Republican and suffragette. Declaring India House open, Hyndman remarked, "As things stands, loyalty to Great Britain means treachery to India. The institution of this India House means a great step in that direction of Indian growth and Indian emancipation, and some of those who are here this afternoon may live to witness the fruits of its triumphant success." Shyamji hoped India House would incubate Indian revolutionaries and Bhikaiji Cama, S. R. Rana, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, Virendranath Chattopadhyaya, and Lala Hardayal were all associated with it.[5]

Later in 1905, Shyamji attended the United Congress of Democrats held at Holborn Town Hall as a delegate of the India Home Rule Society. His resolution on India received an enthusiastic ovation from the entire conference. Shyamji's activities in England aroused the concern of the British government: He was disbarred from Inner Temple and removed from the membership list on 30 April 1909 for writing anti-British articles in The Indian Sociologist. Most of the British press were anti–Shyamji and printed several allegations against him and his newspaper. He defended them boldly. The Times referred to him as the "Notorious Krishnavarma". Many newspapers criticised the British progressives who supported Shyamji and his view. His movements were closely watched by the British secret service, so he decided to shift his headquarters to Paris, leaving India House in charge of Vir Savarkar. Shyamji left Britain secretly before the government tried to arrest him.

Paris and Geneva

He arrived in Paris in early 1907 to continue his work. The British government tried to have him extradited from France without success as he gained the support of many top French politicians. Shyamji's name was dragged into the sensational trial of Mr Merlin, an Englishman, at Bow Street Magistrates' Court, for writing an article in liberators published by Shyamji's friend, Mr. James.

Shyamji's work in Paris helped gain support for Indian Independence from European countries. He agitated for the release of Savarker and acquired great support all over Europe and Russia. Guy Aldred wrote an article in the Daily Herald under the heading of "Savarker the Hindu Patriot whose sentences expire on 24 December 1960", helping create support in England, too. In 1914 his presence became an embarrassment as French politicians had invited King George V to Paris to set a final seal on the Entente Cordiale. Shyamji foresaw this and shifted his headquarters to Geneva. Here the Swiss government imposed political restrictions during the entire period of World War I. He kept in touch with his contacts, but he could not support them directly. He spent time with Dr. Briess, president of the Pro India Committee in Geneva, whom he later discovered was a paid secret agent of the British government.

Post–World War I

He offered a sum of 10,000 francs to the League of Nations to endow a lectureship to be called the President Woodrow Wilson Lectureship for the discourse on the best means of acquiring and safe guarding national independence consistently with freedom, justice, and the right of asylum accorded to political refugees. It is said that the league rejected his offer due to political pressure from British government. A similar offer was made to the Swiss government which was also turned down. He offered another lectureship at the banquet given by Press Association of Geneva where 250 journalists and celebrities, including the presidents of Swiss Federation and the League of Nations. Shyamji's offer was applauded on the spot but nothing came of it. Shyamji was disappointed with the response and he published all his abortive correspondence on this matter in the next issue of the Sociologist appearing in December 1920, after a lapse of almost six years.

Death and commemoration

He published two more issues of Indian Sociologist in August and September 1922, before ill health prevented him continuing. He died in hospital at 11:30 p.m. on 30 March 1930 leaving his wife, Bhanumati Krishnavarma.

News of his death was suppressed by the British colonial government in India. Nevertheless, tributes were paid to him by Bhagat Singh and other inmates in Lahore Jail where they were undergoing a long-term drawn-out trial.[6] Maratha, an English daily newspaper started by Bal Gangadhar Tilak paid tribute to him.

He had made prepaid arrangements with the local government of Geneva and St Georges cemetery to preserve his and his wife's ashes at the cemetery for 100 years and to send their urns to India whenever it became independent during that period. Requested by Paris-based scholar Dr Prithwindra Mukherjee, the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi agreed to repatriate the ashes. Finally on 22 August 2003, the urns of ashes of Shyamji and his wife Bhanumati were handed over to then Chief Minister of Gujarat State Narendra Modi by the Ville de Genève and the Swiss government 55 years after Indian Independence. They were brought to Mumbai and after a long procession throughout Gujarat, they reached Mandvi, his birthplace.[7] A memorial called Kranti Teerth dedicated to him was built and inaugurated in 2010 near Mandvi. Spread over 52 acres, the memorial complex houses a replica of India House building at Highgate along with statues of Shyamji Krishna Varma and his wife. Urns containing Krishna Verma's ashes, those of his wife, and a gallery dedicated to earlier activists of Indian independence movement is housed within the memorial. Krishna Verma was disbarred from the Inner Temple in 1909. This decision was revisited in 2015, and a unanimous decision taken to posthumously reinstated him.[8][9]

In the 1970s, a new town developed in his native state of Kutch, was named after him as Shyamji Krishna Varmanagar in his memory and honor. India Post released postal stamps and first day cover commemorating him. Kuchchh University was renamed after him.

The India Post has issued a postal stamp on shyamji Krishna Varma on 4 October 1989.

Shyamji Krishna Varma 1989 stamp of India

Shyamji Krishna Varma 1989 stamp of India Kranti Teerth, Shyamji Krishna Varma Memorial, Mandvi, Kutch (replica of India House is visible in background)

Kranti Teerth, Shyamji Krishna Varma Memorial, Mandvi, Kutch (replica of India House is visible in background)

References

- ↑ Chandra, Bipan (1989). India's Struggle for Independence. New Delhi: Penguin Books India. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-14-010781-4.

- 1 2 Qur, Moniruddin (2005). History of Journalism. Anmol Publications. p. 123. ISBN 81-261-2355-9.

- ↑ Johnson, K. Paul (1994). The Masters Revealed: Madame Blavatsky and the Myth of the Great White Lodge. SUNY Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-7914-2063-9.

- 1 2 Sundaram, V. (8 October 2006) Pandit Shyamji Krishna Verma, boloji.com. Accessed 28 August 2022.

- ↑ ब्यावरहिस्ट्री डोट काम पर आपका स्वागत है. Beawarhistory.com. Retrieved on 7 December 2018.

- ↑ Sanyal, Jitendra Nath (May 1931). Sardar Bhagat Singh.

- ↑ Soondas, Anand (24 August 2003). "Road show with patriot ash". The Telegraph, Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 17 September 2004. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ↑ "Modi dedicates 'Kranti Teerth' memorial to Shyamji Krishna Verma". The Times of India. 13 December 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Bowcott, Owen (11 November 2015). "Indian lawyer disbarred from Inner Temple a century ago is reinstated". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

Further reading

- Mr. Vishnu Pandya, Mr. Hitesh Bhanushali (1890). Krantiveer's Biography as a Story-Gujarati. Krishna Type Setting Works, Sadra, Dist. -Ahemdabad, State - Gujarat, Country - India.

External links

Media related to Shyamji Krishna Varma at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Shyamji Krishna Varma at Wikimedia Commons