| R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Radial engine |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Wright Aeronautical |

| First run | May 1937 |

| Major applications | Boeing B-29 Superfortress Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcar Douglas A-1 Skyraider Douglas DC-7 Lockheed Constellation Lockheed P-2 Neptune |

| Number built | 29181[1] |

| Developed from | Wright R-1820 Cyclone |

| Developed into | Wright R-4090 Cyclone 22 |

The Wright R-3350 Duplex-Cyclone is an American twin-row, supercharged, air-cooled, radial aircraft engine with 18 cylinders displacing nearly 3,350 cubic inches (54.9 L). Power ranged from 2,200 to over 3,700 hp (1,640 to 2,760 kW), depending on the model. Developed before World War II, the R-3350's design required a long time to mature before finally being used to power the Boeing B-29 Superfortress.

After the war, the engine had matured sufficiently to become a major civilian airliner design, notably in its turbo-compound forms, and was used in the Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation airliners into the 1950s. Its main rival was the 4,360 in3 (71.4 L), 4,300 hp (3,200 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major, first run some seven years after the Duplex-Cyclone's beginnings. The engine is commonly used on Hawker Sea Fury and Grumman F8F Bearcat Unlimited Class Racers at the Reno Air Races.

Design and development

In 1927, Wright Aeronautical introduced its famous "Cyclone" engine, which powered a number of designs in the 1930s. After merging with Curtiss to become Curtiss-Wright in 1929, an effort was started to redesign the engine to the 1,000 horsepower (750 kW) class. The new Wright R-1820 Cyclone 9 first ran successfully in 1935, and became one of the most used aircraft engines in the 1930s and WWII, powering all frontline examples (the -C through -G models) of the B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber aircraft serving in the war, each powerplant assisted by a General Electric-designed turbocharger for maximum power output at high altitudes.

By 1931 Pratt & Whitney had started a development of their equally famous single-row, Wasp nine-cylinder design into a larger and much more powerful fourteen-cylinder, twin-row design — the R-1830 Twin Wasp — of a nearly identical 30-liter displacement figure, that would easily compete with this larger, single-row Cyclone. In 1935 Wright followed P&W's lead, and developed much larger engines based on the mechanics of the Cyclone. The result was two designs with a somewhat shorter stroke, a 14-cylinder design of almost 43 liters displacement that would evolve into the Wright R-2600 Twin Cyclone, and a much larger 18-cylinder design that became the R-3350. A larger twin-row 22-cylinder version, the Wright R-4090 Cyclone 22, was experimented with as a competitor to the 71.5 liter-displacement four-row, 28-cylinder Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major, but was not produced.

With Pratt & Whitney starting development of their own 46 liter-displacement 18-cylinder, twin-row high-output radial as the Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp in 1937, Wright's first R-3350 prototype engines — itself having a nearly 55 liter displacement figure — were initially run in May of the same year. Continued development was slow, both due to the complex nature of the engine, as well as the R-2600 receiving considerably more attention. The R-3350 did not fly until 1941, after the prototype Douglas XB-19 had been redesigned from the Allison V-3420 to accept the R-3350.

Things changed dramatically in 1940 with the introduction of a new contract by the USAAC to develop a long-range bomber capable of flying from the US to Germany with a 20,000 lb (9000 kg) bomb load. Although smaller than the Bomber D designs that led to the Douglas XB-19, the new designs required roughly the same amount of power. When preliminary designs were returned in the summer of 1940, three of the four designs were based on the R-3350. Suddenly the engine was seen as the future of army aviation, and serious efforts to get the design into production started. In 1942 Chrysler started the construction of the Dodge Chicago Plant and the new factory, designed by Albert Kahn, was in full operation by early 1944.

By 1943 the ultimate development of the new bomber program, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, was flying. The engines remained temperamental, and showed an alarming tendency for the rear cylinders to overheat, partially due to minimal clearance between the cylinder baffles and the cowl. A number of changes were introduced into the Superfortress' production line to provide more cooling at low speeds, with the aircraft rushed into operational use in the Pacific in 1944. This proved unwise, as the early B-29 tactics of maximum weights, when combined with the high temperatures of the tropical airfields where B-29s were based, produced overheating problems that were not completely solved, and the engines having an additional tendency to swallow their own valves. Because of a high magnesium content in the potentially combustible crankcase alloy, the resulting engine fires — sometimes burning with a core temperature approaching 5,600 °F (3,100 °C)[2] — were often so intense the main spar could burn through in seconds, resulting in catastrophic wing failure.[3]

Early versions of the R-3350 had carburetors, though the poorly designed elbow entrance to the supercharger led to serious problems with fuel/air distribution. Near the end of WWII, the system was changed to use gasoline direct injection where fuel was injected directly into the combustion chamber. This improved engine reliability. After the war the engine was redesigned and became popular for large aircraft, notably the Lockheed Constellation and Douglas DC-7.

Following the war, the Turbo-Compound[4] system was developed to deliver better fuel efficiency. In these versions, three power-recovery turbines (PRT) were inserted into the exhaust piping of each group of six cylinders, and geared to the engine crankshaft by fluid couplings to deliver more power. The PRTs recovered about 20% of the exhaust energy (around 450 horsepower (340 kW)) that would have otherwise been wasted, but reduced engine reliability (Mechanics tended to call them Parts Recovery Turbines, since increased exhaust heat meant a return of the old habit of the engine destroying exhaust valves). The fuel burn for the PRT-equipped aircraft was nearly the same as the older Pratt and Whitney R-2800, while producing more useful power.[5] Effective 15 October 1957 a DA-3/DA-4 engine cost $88,200.[6]

By this point reliability had improved with the mean time between overhauls at 3,500 hours and specific fuel consumption in the order of 0.4 lb/hp/hour (243 g/kWh, giving a 34% fuel efficiency). Engines in use as of the 2020s are limited to 52 inHg (180 kPa) manifold pressure, giving 2,880 horsepower (2,150 kW) with 100/130 octane fuel (or 100LL) instead of the 59.5 inHg (201 kPa) and 3,400 horsepower (2,500 kW) possible with 115/145, or better, octane fuels, which are no longer available because such formulations are exceedingly toxic due to the extremely high tetraethyllead content of these avgas versions.

Several racers at the Reno Air Races use R-3350s. Modifications on one, Rare Bear, include a nose case designed for a slow-turning prop, taken from an R-3350 used on the Lockheed L-1649 Starliner, mated to the power section (crankcase, crank, pistons, and cylinders) taken from an R-3350 used on the Douglas DC-7. The supercharger is taken from an R-3350 used on the Lockheed EC-121 and the engine is fitted with nitrous oxide injection. Normal rated power of a stock R-3350 is 2,800 horsepower (2,100 kW) at 2,600 rpm and 45 inHg (150 kPa) of manifold pressure. With these modifications, Rare Bear's engine produces 4,000 horsepower (3,000 kW) at 3,200 rpm and 80 inHg (270 kPa) of manifold pressure, and 4,500 horsepower (3,400 kW) with nitrous oxide injection.[7]

Variants

- R-3350-13

- 2,200 shp (1,640 kW)

- R-3350-23

- 2,200 shp (1,640 kW)

- R-3350-24W

- 2,500 shp (1,860 kW)

- R-3350-26W

- 2,800 shp (2,090 kW)

- R-3350-30W

- R-3350-30WA

- R-3350-32W

- 3,700 shp (2,760 kW)

- R-3350-34

- 3,400 shp (2,540 kW)

- R-3350-35A

- 2,200 shp (1,640 kW)

- R-3350-41

- Fuel injected Silverplate variant[8]

- R-3350-42WA

- 3,800 shp (2,830 kW)

- R-3350-53

- 2,700 shp (2,010 kW)

- R-3350-57

- 2,200 shp (1,640 kW)

- R-3350-85

- 2,500 shp (1,860 kW)

- R-3350-89A

- 3,500 shp (2,610 kW)

- R-3350-93W

- 3,500 shp (2,610 kW)

- 972TC18DA1

- Commercial equivalent to the -30W without water injection

- 956C18CA1

- Commercial, similar to the -26W

- 975C18CB1

- Commercial, similar to the 956C18CA1

Applications

- Beechcraft XA-38 Grizzly

- Boeing B-29 Superfortress

- Boeing XC-97 Stratofreighter

- Boeing XPBB Sea Ranger

- Canadair CP-107 Argus

- Consolidated B-32 Dominator

- Curtiss XBTC-2

- Curtiss XF14C

- Curtiss XP-62

- Douglas A-1 Skyraider

- Douglas BTD Destroyer

- Douglas DC-7

- Douglas XB-19

- Douglas XB-31

- Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcar

- Fairchild AC-119

- Grumman F8F Bearcat (See the Rare Bear)

- Hawker Sea Fury

- Lockheed Constellation

- Lockheed L-049 Constellation

- Lockheed C-69 Constellation

- Lockheed L-649 Constellation

- Lockheed L-749 Constellation

- Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation

- Lockheed C-121 Constellation

- Lockheed R7V-1 Constellation

- Lockheed EC-121 Warning Star

- Lockheed L-1649A Starliner

- Lockheed P-2 Neptune

- Lockheed XB-30

- Martin JRM Mars

- Martin XB-33 Super Marauder

- Martin P5M Marlin

- Stroukoff YC-134

Engines on display

- Wright R-3350-89 is on public display at the Aerospace Museum of California

- Wright R-3350 is on public display at Flyhistorisk Museum, Sola, near Stavanger, Norway

- Wright R-3350-35A is on public display at Texas Air Museum - Stinson Chapter, San Antonio, Texas

- Wright R-3350 is on public display in the Mackenzie Engineering Building at Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

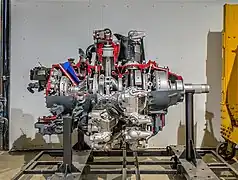

.jpg.webp) R-3350 on display at the Air Zoo

R-3350 on display at the Air Zoo R-3350 on display at Museum of Aviation, Robins AFB

R-3350 on display at Museum of Aviation, Robins AFB R-3350 on display at Carleton University

R-3350 on display at Carleton University

Specifications (R-3350-C18-BA)

Data from Jane's.[9]

General characteristics

- Type: Twin-row 18-cylinder radial engine

- Bore: 6+1⁄8 in (155.6 mm)

- Stroke: 6+5⁄16 in (160.3 mm)

- Displacement: 3,347.9 in3 (54.862 L)

- Length: 76.26 inches (1,937 mm)

- Diameter: 55.78 inches (1,417 mm)

- Dry weight: 2,670 pounds (1,210 kg)

Components

- Valvetrain: Pushrod, two valves per cylinder

- Supercharger: Two-speed single-stage

- Fuel system: Chandler-Evans downdraft carburetor

- Fuel type: 100/130 RON

- Oil system: Dry sump

- Cooling system: Air-cooled

Performance

- Power output: 2,200 hp (1,600 kW) at 2,800 rpm (takeoff)

- Specific power: 0.66 hp/in³

- Compression ratio: 6.85:1

- Specific fuel consumption: Takeoff: 0.38 lb/(hp⋅h) (0.17 kg/(hp⋅h); 0.23 kg/kWh)[10]

- Power-to-weight ratio: 0.82 hp/lb

See also

Related development

- Wright Cyclone series

- Wright R-1300 Cyclone 7

- Wright R-1820 Cyclone 9

- Wright R-2600 Cyclone 14

- Wright R-4090 Cyclone 22

Comparable engines

- BMW 802

- Bristol Centaurus

- Dobrynin VD-4K

- Gnome-Rhône 18L

- Nakajima Homare

- Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major

- Shvetsov ASh-73

Related lists

References

Notes

- ↑ "SUMMARY OF WRIGHT ENGINE SHIPMENTS 1920 – 1930" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-10-10. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ↑ Dreizin, Edward L.; Berman, Charles H. & Vicenzi, Edward P. (2000). "Condensed-phase modifications in magnesium particle combustion in air". Scripta Materialia. 122 (1–2): 30–42. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.488.2456. doi:10.1016/S0010-2180(00)00101-2.

- ↑ "B-29." fighter-planes.com. Retrieved: 15 September 2011.

- ↑ Gunston 2006, p. 247.

- ↑ "The Wright R-3350 Turbo-Compound Engine". Sport Aviation: 20. April 2012.

- ↑ American Aviation 4 Nov 1957 p57

- ↑ "The Bear is Back". Smithsonian Air & Space Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ↑ Doyle p 71

- ↑ Jane's 1998, p. 318

- ↑ Kaiser, Sascha; Donnerhack, Stefan; Lundbladh, Anders; Seitz, Arne (27–29 July 2015). A composite cycle engine concept with hecto-pressure ratio. AIAA/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference (51st ed.). doi:10.2514/6.2015-4028.

Bibliography

- Gunston, Bill. World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines: From the Pioneers to the Present Day. 5th edition, Stroud, UK: Sutton, 2006. ISBN 0-7509-4479-X

- White, Graham. Allied Aircraft Piston Engines of World War II: History and Development of Frontline Aircraft Piston Engines Produced by Great Britain and the United States During World War II. Warrendale, Pennsylvania: SAE International, 1995. ISBN 1-56091-655-9

- Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War II. London. Studio Editions, 1998. ISBN 0-517-67964-7.

- Doyle, David. "B-29 Superfortress Vol. 1" Schiffer Publishing Ltd. 2020 ISBN 978-0-7643-5937-8