| Sheldon Moldoff | |

|---|---|

Moldoff at a convention in his later years. | |

| Born | Sheldon Douglas Moldoff April 14, 1920 New York City, New York |

| Died | February 29, 2012 (aged 91) Fort Lauderdale, Florida |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Penciller |

| Pseudonym(s) | Shelly |

Notable works | Batman, Poison Ivy, Hawkman |

| Awards | Inkpot Award |

| Signature | |

| |

Sheldon Moldoff (/ˈmoʊldɒf/; April 14, 1920 – February 29, 2012)[1] was an American comics artist best known for his early work on the DC Comics characters Hawkman and Hawkgirl, and as one of Bob Kane's primary "ghost artists" (uncredited collaborators) on the superhero Batman. He co-created the Batman supervillains Poison Ivy, Mr. Freeze, the second Clayface, and Bat-Mite, as well as the original heroes Bat-Girl, Batwoman, and Ace the Bat-Hound. Moldoff is the sole creator of the Black Pirate. Moldoff is not to be confused with fellow Golden Age comics professional Sheldon Mayer.

Biography

Early life and career

Born in Manhattan, New York City[2] but mostly raised in The Bronx, he was introduced to cartooning by future comics artist Bernard Baily, who lived in the same apartment house as Moldoff. "I was drawing in chalk on the sidewalk—Popeye and Betty Boop and other popular cartoons of the day—and he came by and looked at it and said, 'Hey, do you want to learn how to draw cartoons?' I said, 'Yes!' He said, 'Come on, I'll show you how to draw.'"[3] He was of Jewish background.[4]

Moldoff sold his first cartoon drawing at age 17. "My first work in comic books was doing filler pages for Vincent Sullivan, who was the editor at National Periodicals",[5] one of the three companies, with Detective Comics Inc. and All-American Publications, that eventually merged to form the modern-day DC Comics. Moldoff's debut was a sports filler that appeared on the inside back cover of the landmark Action Comics #1 (June 1938), the comic book that introduced Superman.[6]

Golden Age

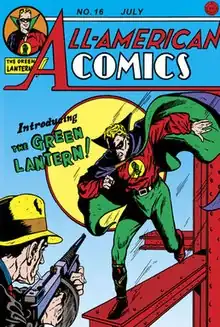

During the late-1930s and 1940s Golden Age of comic books, Moldoff became a prolific cover artist for the future DC Comics. His work includes the first cover of the Golden Age Green Lantern, on issue #16 (July 1940) of All-American's flagship title All-American Comics, featuring the debut of that character created by artist Martin Nodell.[6] Moldoff created the character Black Pirate (Jon Valor) in Action Comics #23 (April 1940),[6] and became one of the earliest artists for the character Hawkman (created by Gardner Fox and Dennis Neville,[6] though sometimes misattributed to Moldoff). Moldoff drew the first image of the formerly civilian character Shiera Sanders in costume as Hawkgirl in All Star Comics #5,[7] based on Neville's Hawkman costume design.

Beginning with Flash Comics #4 (April 1940), Moldoff became the regular Hawkman artist, following Neville's departure from the feature the issue before.[6] He drew the Hawkman portions of the Justice Society of America stories published in All Star Comics as well.[8][9] Moldoff recalled in 2000 that All-American publisher Max Gaines

...took a shine to me. ... He's the one who said, 'We're going to put you on "Hawkman", and do whatever you want with it. Do a good job; I know you can do it." And that was it! ... But when I looked at 'Hawkman' and read a couple of stories, I said to myself, 'This has to be done in a[n Alex] Raymond style.' I could just feel it.... I [had] saved [Raymond Flash Gordon] Sunday [comic strip] pages and the daily papers for years! ... [Gaines] liked my style; he liked the realism. We were competing with the newspapers. When he picked up the Sunday papers, he saw Flash Gordon, Prince Valiant, Terry and the Pirates. When he picked up a comic book, there was a tremendous difference in the quality of the art. And then, all of a sudden, he saw me—an 18-year-old coming around, and I'm almost a student of Raymond, and by God, the stuff looks good—it looks like Raymond! We all leaned on these guys to learn—and we were very lucky, because while we were learning, we were selling the product... I spent a lot of time on it. I had books on anatomy and shadows and wrinkles; I studied, and I worked very hard on it, and I think it showed.[3]

Drafted into World War II military service in 1944, Moldoff returned to civilian life in 1946, drawing for Standard, Fawcett, Marvel and Max Gaines' EC Comics. For EC he drew Moon Girl, continuing with that character for Bill Gaines.[10]

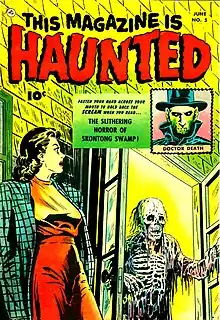

When superhero comics went out of fashion in the postwar era, Moldoff became an early pioneer in horror comics, packaging two such ready-to-print titles in 1948. He recalled in 2000 that, "I had shown This Magazine Is Haunted and Tales of the Supernatural to [Fawcett Comics'] Will Lieberson before I showed them to [EC Comics'] Bill Gaines, because I trusted Will Lieberson much more. He showed it to the big guys at Fawcett, and he said, 'Shelly, Fawcett doesn't want to get into horror now; they don't want to touch that'".[3]

Moldoff then did approach Gaines with the package, signing a contract stipulating that he would be paid a royalty percentage if the books were successful. Several months later, when EC's Tales From the Crypt hit the newsstands, Gaines reneged on the deal, Moldoff recalled in 2000, with EC attorney Dave Alterbaum threatening to blacklist Moldoff if he took legal action.[3] Afterward, said Moldoff, "Will Lieberson said, 'Let me bring it back to Fawcett again, and see if they'll take the title'. And so they did; they took This Magazine Is Haunted and Worlds of Fear and then Strange Suspense Stories. What they did was pay me $100 for the title, and give me as much work as I wanted, and I also did the covers. So that went on that way".[3]

Moldoff, who received no royalty there, either, created the cadaverous host Doctor Death.

1950s and 1960s

In 1953, Moldoff became one of the primary Batman ghost artists who, along with Win Mortimer and Dick Sprang, drew stories credited to Bob Kane, following Kane's style and under Kane's supervision. While Sprang ghosted as a DC employee, Moldoff, in a 1994 interview given while Kane was alive, described his own secret arrangement:

I worked for Bob Kane as a ghost from ' 53 to ' 67. DC didn't know that I was involved; that was the handshake agreement I had with Bob: 'You do the work don't say anything, Shelly, and you've got steady work'. No, he didn't pay great, but it was steady work, it was security. I knew that we had to do a minimum of 350 to 360 pages a year. Also, I was doing other work at the same time for [editors] Jack Schiff and Murray Boltinoff at DC. They didn't know I was working on Batman for Bob. ... So I was busy. Between the two, I never had a dull year, which is the compensation I got for being Bob's ghost, for keeping myself anonymous.[5]

Moldoff and various writers created several new characters for the Batman franchise including the Batmen of All Nations,[11] Ace the Bat-Hound,[12] the original Batwoman,[13] the Calendar Man,[14] Mr. Freeze,[15] Bat-Mite,[16] the original Bat-Girl,[17] and the second Clayface.[18] Most of these characters were phased out in 1964 after a change in editors. Gardner Fox and Moldoff revived the Riddler in Batman #171 (May 1965).[19] Other Batman foes introduced by Moldoff include Poison Ivy[20] and the Spellbinder.[21]

Moldoff was let go by DC in 1967, along with many other prominent writers and artists who had made demands for health and retirement benefits.[22] His final Batman stories were published in Batman #199 and Detective Comics #372 (both cover dated February 1968).[6] He turned to animation, doing storyboards for such animated TV series as Courageous Cat and Minute Mouse, and wrote and drew promotional comic books given away to children at the Burger King, Big Boy, Red Lobster, and Captain D's[23] restaurant and fast-food chains, as well as through the Atlanta Braves Major League Baseball team.[24] When Moldoff illustrated a chapter of the Evan Dorkin project Superman and Batman: World's Funnest in 2000, it was his first work for DC Comics in over 30 years.[6]

Later life

Moldoff retired to Florida with his wife Shirley.[24] His family included sons Richard Moldoff and Kenneth Moldoff and daughter Ellen Moldoff Stein.[1] He died at age 91 on February 29, 2012, following kidney failure. He was the last surviving contributor of Action Comics #1.[25]

Awards

Sheldon Moldoff received an Inkpot Award in 1991.[26]

Bibliography

DC Comics

- Action Comics #1–2, 5–8, 10, 12, 15–17, 20–36, 38–42 (1938–1941)

- Adventure Comics #313, 320–322, 334–337, 339, 341–342, 346 (Legion of Super-Heroes) (inker) (1963–1966)

- All-American Comics #27 (Green Lantern); #49 (Sargon the Sorcerer) (1941–1943)

- All-Flash #6 (1942)

- All Star Comics #1–23 (1940–1944)

- Batman #81–92, 94–175, 177–181, 183–184, 186, 188–192, 194–196, 199 (1954–1968)

- Blackhawk #110–112, 119, 121–122, 127, 133–135, 139–147, 149, 151–161, 163–164, 168–169, 171–173, 181, 184 (inker) (1957–1963)

- The Brave and the Bold #54 (Kid Flash/Aqualad/Robin) (inker) (1964)

- Comic Cavalcade #1–3, 7, 14 (1942–1946)

- Detective Comics #199–207, 213–215, 218–219, 221, 223, 225, 227–228, 230–231, 233–239, 241–242, 244–247, 249–263, 266–295, 297–298, 300–310, 312–317, 319–326, 328, 330, 332, 334, 336, 338, 340, 343, 344, 346, 348, 350, 353, 354–356, 358, 360, 362, 364–365, 368, 370, 372 (1953–1968)

- Flash Comics #1–61 (1940–1945)

- Gang Busters #29, 53, 55, 58, 61, 65–66 (1952–1958)

- House of Mystery #2, 16, 34, 60–62, 66–67, 80, 84, 139 (1952–1963)

- House of Secrets #5–6, 15, 18, 21 (1957–1959)

- Mr. District Attorney #18, 35, 49, 60–66 (1950–1958)

- My Greatest Adventure #16, 68 (1957–1962)

- Mystery in Space #99 (1965)

- Sea Devils #16–35 (inker) (1964–1967)

- Sensation Comics #1–31 (Black Pirate); #34 (Sargon the Sorcerer) (1942–1944)

- Strange Adventures #187, 197 (inker) (1966–1967)

- Superboy #118, 121, 146, 148 (inker) (1965–1968)

- Superman #145, 147–148, 188 (inker) (1961–1966)

- Superman and Batman: World's Funnest #1 (among other artists) (2001)

- Superman's Girl Friend, Lois Lane #57 (inker) (1965)

- Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #50, 85, 87–88 (inker) (1961–1965)

- Tales of the Unexpected #4–7, 10, 14, 16, 24, 48, 68, 84 (1956–1964)

- Wonder Woman #1–6 (1942–1943)

- World's Finest Comics #68, 104, 106–108, 110–113, 115, 118, 122–123, 125–127, 129, 132, 135, 139–140, 148–151, 157 (inker) (1954–1966)

EC Comics

- Animal Fables #7 (1947)

- Crime Patrol #7 (1948)

- Gunfighter #5–6 (1948)

- The Happy Houlihans #1 (1947)

- International Comics #1–5 (1947)

- International Crime Patrol #6 (1948)

- Moon Girl #2–6 (1947–1949)

- Moon Girl and the Prince #1 (1947)

- Moon Girl Fights Crime #7–8 (1949)

- War Against Crime! #4 (1948)

Fawcett Comics

- Marvel Family #25 (1948)

Marvel Comics

- Astonishing #33 (1954)

- Combat Casey #12 (1953)

- Journey into Unknown Worlds #17 (1953)

- Menace #10 (1954)

- Mystic #18, 29 (1953–1954)

- Strange Tales #20 (1953)

- Uncanny Tales #23 (1954)

Quality Comics

- Hit Comics #25–30 (Kid Eternity) (1942–1943)

References

- 1 2 "In Memory of Sheldon Douglas Moldoff April 14, 1920 – February 29, 2012". Coral Springs, Florida: Kraeer Funeral Home and Cremation Center. Archived from the original on December 31, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2012.

- ↑ "Sheldon Moldoff". Lambiek Comiclopedia. June 14, 2012. Archived from the original on September 24, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "A Moon... A Bat... A Hawk: A Candid Conversation With Sheldon Moldoff". Alter Ego. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. 3 (4). Spring 2000. Archived from the original on December 1, 2010.

- ↑ "Jews Get Geek on at Comic-Con". July 22, 2009.

- 1 2 1994 Sheldon Moldoff interview, first published in Alter Ego # 59 (June 2006), p. 15

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sheldon Moldoff at the Grand Comics Database

- ↑ "All Star Comics #5 (June–July 1941)". Grand Comics Database.

- ↑ Wallace, Daniel; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "1940s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Thomas, Roy (2000). "The Men (and One Woman) Behind the JSA: Its Creation and Creative Personnel". All-Star Companion Volume 1. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 1-893905-055.

- ↑ Ringgenberg, Steven (March 7, 2012). "Sheldon Moldoff, April 14, 1920 – February 29, 2012". The Comics Journal. Seattle, Washington. Archived from the original on May 31, 2012.

- ↑ Manning, Matthew K.; Dougall, Alastair, ed. (2014). "1950s". Batman: A Visual History. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 56. ISBN 978-1465424563.

Writer Edmond Hamilton and artist Sheldon Moldoff created an international club of sorts for super heroes from other nations.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Irvine, Alex "1950s" in Dolan, p. 77: "Batman #92 (July 1955) Once Superman had a dog, Batman got one too, in 'Ace, the Bat-Hound!' In the story by writer Bill Finger and artist Sheldon Moldoff, Batman and Robin found a German Shepherd called Ace."

- ↑ Irvine "1950s" in Dolan, p. 80: "In the story 'The Batwoman' by writer Edmond Hamilton and penciler Sheldon Moldoff (as Bob Kane), Bruce Wayne took notice of a young admirer who...was fighting crime while wearing a bat-costume very similar to the one the Dark Knight wore."

- ↑ Irvine "1950s" in Dolan, p. 91: "Detective Comics #259 saw the first appearance of Julian Gregory Day, otherwise known as the Calendar Man in 'The Challenge of the Calendar Man' written by Bill Finger and drawn by Sheldon Moldoff."

- ↑ Irvine "1950s" in Dolan, p. 92: "The Dynamic Duo battle the frosty foe Mr. Zero in a story by Dave Wood and with art by Sheldon Moldoff in Batman #121...The 1960s Batman TV series, starring Adam West, included the character of Mr. Zero but renamed him Mr. Freeze."

- ↑ Irvine "1950s" in Dolan, p. 94: "The impish Bat-Mite made his first appearance in Detective Comics #267, care of writer Bill Finger and artist Sheldon Moldoff."

- ↑ McAvennie, Michael "1960s" in Dolan, p. 102: "Betty Kane assumed the costumed identity of Bat-Girl in this tale by writer Bill Finger and artist Sheldon Moldoff."

- ↑ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 103: "Scribe Bill Finger and artist Sheldon Moldoff reshaped the face of evil with the second – and perhaps most recognized – Clayface ever to challenge the Dark Knight."

- ↑ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 114: "Nearly eighteen years had passed since the Riddler last tried to stump Batman and Robin. Therefore, when writer Gardner Fox and artist Sheldon Moldoff released Edward Nigma, the villain insisted that he had reformed."

- ↑ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 118: "Poison Ivy first cropped up to plague Gotham City in issue #181 of Batman. Scripter Robert Kanigher and artist Sheldon Moldoff came up with a villain who would blossom into one of Batman's greatest foes."

- ↑ McAvennie "1960s" in Dolan, p. 119: "Batman was hopelessly entranced within 'The Circle of Terror' rendered by new villain Spellbinder, and produced by scripter John Broomw and artist Sheldon Moldoff."

- ↑ Barr, Mike W. (Summer 1999). "The Madames & the Girls: The DC Writers Purge of 1968". Comic Book Artist. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (5).

- ↑ Cassell, Dewey (December 2016). "Captain D's Exciting Adventures". Back Issue!. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing (93): 44–45.

- 1 2 "Sheldon Moldoff". Comic Art & Grafix Gallery. 2006. Archived from the original on March 3, 2011.

- ↑ "News from ME – Mark Evanier's blog".

- ↑ "Inkpot Award Winners". Hahn Library Comic Book Awards Almanac. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012.

Further reading

- Sheldon Moldoff interview, Alter Ego #59, June 2006, pp. 14–23; previously unpublished interview conducted in 1994 for Comics Interview magazine.

- Schoellkopf, Andrea. "Convention Indulges Comic Book Addicts," Albuquerque Journal (January 16, 1995), p. A1 — profile of Moldoff

External links

- Sheldon "Shelly" Moldoff (official site). WebCitation archive

- Sheldon Moldoff interview (July 1999). "'I Never Went a Day Without Work'". The Comics Journal. No. 214. pp. 90–107. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012.

- Sheldon Moldoff at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Sheldon Moldoff at Mike's Amazing World of Comics