Seyðisfjörður | |

|---|---|

Seyðisfjörður | |

Coat of arms | |

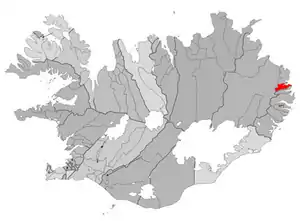

Location of the town | |

Seyðisfjörður | |

| Coordinates: 65°15′47″N 14°0′32″W / 65.26306°N 14.00889°W | |

| Country | Iceland |

| Region | Eastern Region |

| Municipality | Múlaþing |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 676 |

| Postal code(s) | 710 |

Seyðisfjörður (Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈseiːðɪsˌfjœrðʏr̥] ⓘ) is a town in the Eastern Region of Iceland at the innermost point of the fjord of the same name. The town is located in the municipality of Múlaþing.

A road over Fjarðarheiði mountain pass (elevation 600 m or 2,000 ft) connects Seyðisfjörður to the rest of Iceland; 27 kilometres (17 miles) to the ring road and Egilsstaðir. Seyðisfjörður is surrounded by mountains with the most prominent Mt. Bjólfur to the west (1085 m) and Strandartindur (1010 m) to the east. The fjord itself is accessible on each side from the town, by following the main road that leads through the town. Further out the fjord is fairly remote but rich with natural interests including puffin colonies and ruins of former activity such as nearby Vestdalseyri [ˈvɛstˌtalsˌeiːrɪ], from where the local church was transported.

History

Settlement in Seyðisfjörður traces back to the early period of settlement in Iceland. The first settler was Bjólfur, who occupied the entire fjord. The ruin of a burned-down stave church at Þórunnarstaðir [ˈθouːrˌʏnːarˌstaːðɪr̥] was excavated in 1998-1999 and carbon-dated to the 11th century.[2]

The town settlement in the Seyðisfjörður area started in 1848. The town was settled by Norwegian fishermen. These settlers also built some of the wooden buildings which still exist in the town. Another now-deserted settlement nearby in the fjord, Vestdalseyri was the site for the world's first modern industrialized whaling station. It was established in 1864 by American whaler Thomas Welcome Roys and run by him and his workforce until 1866. Both settlements served primarily as fishing and trading posts. The first telegraph cable connecting Iceland to Europe made landfall in Seyðisfjörður in 1906, making it a hub for international telecommunications well past the middle of last century. In 1913, a dam was made in the main river, harnessing power for the country's first high-voltage AC power plant together with a distribution network for street lighting and home use,[3] also the first of its kind in Iceland. Seyðisfjörður was used as a base for British/American forces during World War II and remnants of this activity are visible throughout the fjord, including a landing strip no longer in use and an oil tanker SS El Grillo that was bombed and sunk. It remains a divers' wreck at the bottom of the fjord.

With the recent demise of the local fish-processing plant, the village has shifted its economy to tourism. It still remains a significant fishing port on the east coast of Iceland, with harbours, ship construction facilities and a slip.

In December 2020, a series of mudflows hit the town after days of heavy raining, destroying several houses.[4] After 10 houses where damaged on 18 December, including the headquarters of the local SAR team,[5] a complete evacuation of the town was ordered.[6][7][8] A month after the mudflow had hit the town, the damage was fully estimated. In all, 39 houses had been damaged, twelve of which being completely destroyed and five more significantly damaged. The total damage was estimated by the Government of Iceland at over 1 billion Icelandic Króna (US$7.5m).[9] Residents were allowed to return to their homes (if not destroyed) in October 2021 after protections were installed.[10]

Overview

.jpg.webp)

The town of Seyðisfjörður is well known for its old wooden buildings and has remnants of urban street configurations within its urban fabric. There is a camping ground, facilities for campers, hotels, a swimming pool, a library, hospital, post office, liquor store, and other retail activity. Seyðisfjörður also has a vibrant cultural scene with an arts centre, the Technical Museum of East Iceland[11] and the only two cinemas in the east of Iceland. The LungA Art Festival takes place in Seyðisfjörður in July,[12] and LungA School, an independent art school, that runs outside of the summer months.[13][14] The renowned Swiss artist Dieter Roth had a residence and art studio in Seyðisfjörður. Along with others, Roth created a visual art collective in 1996. The Skaftfell Center for Visual Art was later established in 1998. It is the principal center for visual art in the eastern region of Iceland. The center is open to the public and houses an exhibition space, a library of artist books, and a bistro. [15]

There are several waterfalls in the town. A popular hiking path starts at the town center, following the East bank of the Fjarðará, the river that flows through the center of town. Further up the river there are 25 waterfalls. During the winter, a skiing area is used in Fjarðarheiði mountain pass.

Skálanes nature and heritage centre can be found 17 km (10.6 mi) east of the town. The nature reserve is home to a diverse range of wildlife, as well as catering for visitors and anyone wanting to explore the south side of the fjord.

The 2015 Icelandic mystery television series Trapped (Icelandic: Ófærð) is set in the town, and was partially filmed there. The series aired on BBC4 in the UK in early 2016.[16][17]

Transport

Port

Every week the car ferry MS Norröna of Smyril Line comes to Seyðisfjörður from Hirtshals in Denmark and Tórshavn in the Faroe Islands. It is the only car ferry between Iceland and other countries.

Roads

Seyðisfjörður is connected to the Icelandic ring road Route 1 at Egilsstaðir, via Route 93 which departs west from Seyðisfjörður. Route 951 travels east along the northern side of Seyðisfjörð and Route 952 also travels east, but along the southern side of the fjord.

Sports

The local football club Huginn play in Iceland's third tier (3rd Division). The colours of their kit are yellow and black.

Climate

Seyðisfjörður has a tundra climate (Koppen ET), bordering on subpolar oceanic (Cfc). However, the high annual precipitation over 1,650 mm (65 in) and the drying trend in summer are very atypical for tundra areas, which are normally very dry and peak in precipitation in summer.

| Climate data for Seyðisfjörður (1981-2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.5 (63.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.0 (77.0) |

22.0 (71.6) |

20.7 (69.3) |

18.0 (64.4) |

27.0 (80.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

2.9 (37.2) |

3.1 (37.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.0 (55.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.4 (43.5) |

4.4 (39.9) |

2.7 (36.9) |

6.9 (44.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.2 (31.6) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

1.4 (34.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

7.8 (46.0) |

9.9 (49.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.8 (38.8) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

3.8 (38.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.5 (25.7) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

1.8 (35.2) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.1 (44.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.7 (33.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −18.0 (−0.4) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−9.9 (14.2) |

−14.0 (6.8) |

−15.8 (3.6) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 210.7 (8.30) |

156.1 (6.15) |

160.5 (6.32) |

94.2 (3.71) |

67.0 (2.64) |

55.9 (2.20) |

56.8 (2.24) |

95.0 (3.74) |

173.4 (6.83) |

214.2 (8.43) |

178.1 (7.01) |

188.6 (7.43) |

1,650.5 (65) |

| Source: Icelandic Met Office[18] | |||||||||||||

Twin towns – sister cities

Seyðisfjörður is the twin town of Sandur in the Faroe Islands.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ "Seyðisfjarðarkaupstaður". Samband íslenskra sveitarfélaga (in Icelandic). 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ "Viking Archaeology - the Early Medieval Church at Seydisfjordur".

- ↑ "Rafveita Seyðisfjarðar". timarit.is (in Icelandic). Retrieved 2023-11-11.

- ↑ Þórhildur Þorkelsdóttir (18 December 2020). "Bærinn er í rúst". RÚV (in Icelandic). Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ Viðar Guðjónsson (18 December 2020). "Óttaðist að þetta væri hans síðasta". Morgunblaðið (in Icelandic). Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ "Minnst tíu hús skemmdust þegar stór skriða féll". Vísir.is (in Icelandic). 18 December 2020. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ Freyr Gígja Gunnarsson; Hildur Margrét Jóhannsdóttir (18 December 2020). "Ætla að rýma Seyðisfjörð - minnst tíu hús skemmd". RÚV (in Icelandic). Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ Freyr Rögnvaldsson (18 December 2020). "Við erum öll í sjokki". Stundin (in Icelandic). Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ Friðjónsdóttir, Hólmfríður Dagný (26 January 2021). "17 hús á Seyðisfirði ónýt eða mikið skemmd". Icelandic National Broadcasting Service. RÚV. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ↑ "Seyðisfjörður Residents May Return Home". Iceland Review. 2021-10-13. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ "Technical Museum Seydisfjordur - history and local heritage". seydisfjordur.org. 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ "LungA Art Festival". Visit Seyðisfjörður. 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ "Lighting up the Darkness in the East". icenews.is. 19 February 2016. Retrieved 2023-07-24.

- ↑ Kelly, Robert (2020). Collaborative Creativity: Educating for Creative Development, Innovation and Entrepreneurship. Edmonton, Alberta: Brush Education Incorporated. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-550-59837-7.

- ↑ "The Dieter Roth Academy at Skaftfell – Center for Visual Art, East Iceland". skaftfell.is. 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ "Trapped". BBC Four. 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ Wollaston, Sam (15 February 2016). "Trapped review: stuck in a stormy, moody fjord with a killer on the loose? Yes please". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ↑ "Monthly Temperature and Precipitation Averages for Seyðisfjörður". Icelandic Meteorological Office. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ↑ "Vinabæir". sfk.is (in Icelandic). Seyðisfjörður. Retrieved 2020-02-12.

.jpg.webp)

_(Kenny_McFly).jpg.webp)