| Marketing |

|---|

Sex appeal in advertising is a common tactic employed to promote products and services.[1] Research indicates that sexually appealing content, including imagery, is often used to shape or alter the consumer's perception of a brand, even if it is not directly related to the product or service being advertised. This approach, known as "sex sells," has become more prevalent among companies, leading to controversies surrounding the use of sexual campaigns in advertising.[2][1]

Contemporary mainstream advertising, across various media platforms such as magazines, online, and television, frequently incorporates sexual elements to market a wide range of branded goods and services. Provocative images of attractively dressed men and women are commonly used to promote clothing, alcohol, beauty products, and fragrances. Renowned brands like Calvin Klein, Victoria's Secret, and Pepsi use such imagery to cultivate an alluring media presence.

In some cases, sexual content is overtly displayed, while in others, it is subtly integrated with imperceptible cues aimed at influencing the target audience. Furthermore, sexual content has been employed to promote mainstream products that were not traditionally associated with sex. For instance, the Dallas Opera's marketing of the more suggestive aspects of its performances is believed to have contributed to a boost in ticket sales.[3][4]

The effectiveness of sex appeal in advertising varies depending on the cultural context and the gender of the recipient, though these aspects are subject to further research and discussion.

Concept

Gender Advertisements,[5] a 1979 book by Canadian social anthropologist Erving Goffman, is a series of studies of visual communication and how gender representation in advertising communicates subtle, underlying messages about the sexual roles projected by masculine and feminine images in advertising. The book is a visual essay about sex roles in advertising and the symbolism implied in the depictions of men and women in advertising.

When couples are used in an advertisement, the sex roles played by each partner also sends out messages. The interaction of the couple may send out a message of relative dominance and power, and may stereotype the roles of one or both partners. Usually the message is very subtle, and sometimes advertisements attract interest by changing stereotypical roles. For example, companies including Spotify, Airbnb, Lynx and Amazon.com have used same-sex couples in adverts.[6] These adverts appeal to same-sex couples; they also create the image that these companies are tolerant, allowing them to appeal to a wider consumer audience.

As many consumers and professionals are thinking people, sex may be used to grab a viewer's attention, but this is likely short-term success. Whether using sex in advertising is effective depends on the product.[7] About three-quarters of advertisements using sex to sell the product are communicating a product-related benefit, such as the product making its users more sexually attractive.

Daily exposure on social media by adolescents to these types of influences can affect their development. Younger teenage girls are drawn to these ads in order to learn about romance and relationships. [8]

Correlational studies have linked sociodemographic variables to adolescent viewing habits. This can include (but not limited to) sex, age, and even ethnicity. Adolescents who watch and listen to a lot of media are more likely than less regular audiences to consider stereotypes of sex roles on TV as realistic.

Types

Physical attractiveness

.jpg.webp)

The use of physically attractive models in advertising is a form of sex in advertising. Physical attractiveness can be conveyed through facial beauty, physique, hair, skin complexion as well as by the model's inferred personality. This form of sex in advertising is effective as it draws attention and influences the overall feeling of the ad. Furthermore, such ads create an association between physical attractiveness and the product which sends a message to the consumer that buying and using the product will help them achieve that physique.[9] The sexual arousal possibly elicited by physical attractiveness in adverts is thought to transfer onto the advertised product.[10]

Sexual behavior

.jpg.webp)

Marketers often use tactics such as sexual imagery in their advertisements to capture the consumer's attention for longer.[11] Sex in advertising is also incorporated using hints of sexual behavior. The latter is communicated by the models using flirtatious body language, open posture and making eye contact with the viewer. Sexual behavior can also be displayed using several models interacting in a more or less sexual way. Sexual behavior in advertising is used to arouse sexual interest from the viewer.[9] Research has shown that sexual arousal elicited by an advert subsequently affects the overall ad evaluation and the chances of future purchase.[10]

For example, in a Guess clothing advert, while the models are physically attractive, it is their behavior such as position, posture and facial expressions that communicate sexual interest to the viewer. Women are often shown as being shorter, put in the background of images, shown in more 'feminine' poses than men, and generally present a higher degree of 'body display' than men in print advertisements.[12]

Sexual embeds

Sexual embeds are a controversial form of sex in advertising. They are a powerful technique that advertising agencies do not want consumers to consciously notice. They are subliminal elements that are detected as sexual information solely at the subconscious level. Sexual embeds can take the form of objects or words that, at the subconscious level (or when occasionally consciously identified) explicitly depict sexual acts or genitalia. For example, a perfume bottle could mimic a phallic shape and its positioning could suggest sexual intercourse. Embeds are especially effective as they unconsciously trigger sexual arousal in the consumer which drives motivation and goal directed behavior such as purchase intention.[9]

Gender roles

After women achieved the vote in the United States, Britain and Canada in the 1920s, advertising agencies exploited the new status of women. For example, they associated driving an automobile with masculinity, power, control, and dominance over a beautiful woman sitting alongside. More subtly, they published automobile ads in women's magazines, at a time when the vast majority of purchasers and drivers were in fact men. The new ads promoted themes of women's liberation while also delineating the limits of this freedom. Automobiles were more than practical devices, they were also highly visible symbols of affluence, mobility and modernity. The ads offered women a visual vocabulary to imagine their new social and political roles as citizens and to play an active role in shaping their identity as modern women.[13]

History

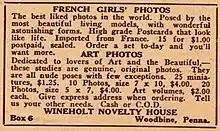

The earliest known use of sex in advertising is by the Pearl Tobacco brand in 1871, which featured a naked maiden on the package cover. In 1885, W. Duke & Sons inserted trading cards into cigarette packs that featured sexually provocative starlets. Duke grew to become the leading American cigarette brand by 1890.[14]

Other early forms of sex appeal in advertising include woodcuts and illustrations of attractive women (often unclothed from the waist up) adorning posters, signs, and ads for saloons, tonics, and tobacco. In several notable cases, sex in advertising has been claimed as the reason for increased consumer interest and sales.

Sex and soap

Woodbury's Facial Soap, a woman's beauty bar, was almost discontinued in 1911. The soap's sales decline was reversed, however, with ads containing images of romantic couples and promises of love and intimacy for those using the brand.[15] Jōvan Musk Oil, introduced in 1971, was promoted with sexual entendre and descriptions of the fragrance's sexual attraction properties. As a result, Jōvan, Inc.'s revenue grew from $1.5 million in 1971 to $77 million by 1978.[16]

Kamasutra condoms in India

In 1991, J.K. Chemicals Group asked the Bombay office of Lintas Bombay to develop a campaign for a new condom brand. The problem was that in the late 1940s, the Nehru government had launched a major population limitation program to reduce India's birthrate. The program was very heavy-handed, using coercion, and demanding that men use condoms. The product therefore signified an oppressive governmental intrusion. The agency head hit on the idea of a pleasurable condom, "So when the user hears the brand name, he says, "Wow. It's a turn on. Not a turn off." A brainstorming session hit on the name "Kamasutra", which refers to an ancient Sanskrit treatise on lovemaking and the sculptures at temples that illustrate the positions involved. The term was known to well-educated Indians, the intended audience. Correctly predicting the huge impact the campaign would have, the agency purchased all the advertising space in the popular glamour magazine Debonair and filled it with erotic images of Bollywood actors and actresses promoting Kamasutra condoms. A television commercial followed featuring a steamy shower scene. The television ad was censored but the print campaign proved highly successful.[17][18]

Benetton

The Italian clothing company Benetton gained worldwide attention in the late 20th century for its saucy advertising, inspired by its art director Oliviero Toscani. He started with multicultural themes, tied together under the campaign "United Colors of Benetton" then became increasingly provocative with interracial groupings, and unusual sexual images, such as a nun kissing a priest.[19]

Calvin Klein - sex and jeans

Calvin Klein of Calvin Klein Jeans has been at the forefront of this movement to use sex in advertising, having claimed, "Jeans are about sex. The abundance of bare flesh is the last gasp of advertisers trying to give redundant products a new identity." Calvin Klein's first controversial jeans advertisement showed a 15-year-old Brooke Shields, in Calvin Klein jeans, saying, "Do you want to know what gets between me and my Calvins? Nothing."[20] Calvin Klein has also received media attention for its controversial advertisements in the mid-1990s. Several of Calvin Klein's advertisements featured images of teenage models, some "who were reportedly as young as 15" in overly sexual and provocative poses.[21] Although Klein insisted that these advertisements were not pornographic, some considered the campaign as a form of "soft porn" or "kiddie porn" that was exploitative, shocking, and suggestive. In 1999, Calvin Klein was the subject of more controversy when it aired advertisements of young children who were only wearing the brand's underwear. This "kiddie underwear ad campaign" was pulled only one day after it aired as a result of public backlash.[22] A spokesperson from Calvin Klein insisted that these ads were intended "to capture the same warmth and spontaneity that you find in a family snapshot."[21]

The film industry

Film studios often make use of provocative movie posters in order to increase publicity and draw in larger audiences. One example is the iconic poster for Quentin Tarantino's 1994 film Pulp Fiction, in which Uma Thurman lies on her front, wearing a low-cut top and stilettos and smoking a cigarette despite the fact that, in the actual movie, she wears a button-down shirt that is far less revealing.[23] The idea that "sex sells" has also led to film studios going a step further - rather than dressing female stars in a certain way simply to promote the movie, they base their actual costume design around this concept. For example, in the 2004 film Catwoman, Halle Berry simply wore a black push-up bra with S&M inspired straps, heavily ripped leather trousers and heels with a cat mask and whip,[24] which commentators said "oozed overt [...] sexuality".[25] This costume was a move away from Catwoman's skin-tight black suit that she wears for the majority of her appearances within DC Comics and thus, despite being entirely more revealing, was actually not a popular decision among fans of the character.

Effectiveness

Effective use

Gallup & Robinson, an advertising and marketing research firm, has reported that in more than 50 years of testing advertising effectiveness, it has found the use of the erotic to be a significantly above-average technique in communicating with the marketplace, "...although one of the more dangerous for the advertiser. Weighted down with taboos and volatile attitudes, sex is a Code Red advertising technique ... handle with care ... seller beware; all of which makes it even more intriguing." This research has led to the popular idea that "sex sells".[26]

Marketing strategies centered around sex have been successful. Abercrombie & Fitch used sex to market their brand in a variety of ways, including store greeters dressed only in underwear, models working in store and topless models on the bags. Employees were hired based on physical attractiveness.[27] This strategy was aimed at teenagers and young adults, who are the most impressionable consumer group and have significant disposable income. During the late 1990s, the company produced a magazine/catalogue (magalog), featuring semi-nude or nude models. The magalog was a success, with A&F issuing over 1.5 million copies. The use of sexual branding raised their revenue from $85 million in 1993 to $1.35 billion in 2002.[28] A&F have expressed that they will move away from sexual marketing, and focus on showcasing product and trends.[29]

Sexuality in advertising is extremely effective at attracting the consumer's attention and once it has their attention, to remember the message.[30] This solves the greatest problem in advertising of getting the potential buyer to look at and remember the advertisement. However, the introduction of attraction and especially sexuality into an ad often distracts from the original message and can cause an adverse effect of the consumer wanting to take action.[31]

Ineffective use

There are some studies that contradict the theory that sex is an effective tool for improving finances and gathering attention. A study from 2009 found that there was a negative correlation between nudity and sexuality in movies, and box office performance and critical acclaim.[32] A 2005 research by MediaAnalyzer has found that less than 10% of men recalled the brand of sexual ads, compared to more than 19% of non sexual ads; a similar result was found in women (10.8% vs. 22.3%). It is hypothesized by that survey, that this is a result of a general numbing caused by overuse of sexual stimuli[33] in advertising.

In another experimental study conducted on 324 undergraduate college students, Brad Bushman, professor and Chair of Mass Communication at Ohio State University, examined brand recall for neutral, sexual or violent commercials embedded in neutral, sexual or violent TV programs. He found that brand recall was higher for participants who saw neutral TV programs and neutral commercials versus those who saw sexual or violent commercials embedded in sexual or violent TV programs.[34] Other studies have found that sex in television is extremely overrated and does not sell products in ads. Unless sex is related to the product (such as beauty, health or hygiene products), there is no clear effect.[35][36]

Using sex may attract one market demographic while repelling another at the same time. The overt use of sexuality to promote breast cancer awareness, through fundraising campaigns like "I Love Boobies" and "Save the Ta-tas", is effective at reaching younger women, who are at low risk of developing breast cancer, but angers and offends some breast cancer survivors and older women, who are at higher risk of developing breast cancer.[37]

In addition, sexually objectified content fails to achieve its goal of brand recall, a study by Vargas & Mensa (2020) shows.[38] Despite the use of sex in marketing to influence men, Vargas & Mensa (2020) study highlights that young women are more influenced; thus, the approach can be ineffective when directed towards male products.

Gender differences

Recent research indicates that the use of sexual images of females in ads negatively affects women's interest.[39] Research shows that females were more likely than males to be portrayed as nude, wearing sexual clothing or only a partial amount of clothing.[40] A study from the University of Minnesota in 2013 of how printed ads with sexual content affects women clearly showed that women are not attracted to them except in the case of products being luxurious and expensive.[41] Besides alienating women, there is a serious risk that the audience in general will reduce support for organisations that uses the sexual images of women without a legitimate reason.[42]

Further research[43] found that men have a positive attitude to sexual adverts, whereas women have a negative response to them; this study used an advert with both a male and female. This was thought to be because women had lower average sex drives than men. Another theory for this difference is that evolution has led men to seek casual sex, contrary to women who value commitment and intimacy in the context of a sexual relationship.[44] In adverts sex tends to be represented in its own right and not as part of a relationship leading to the difference in responses. This theory is supported by research which found that women respond less negatively to sexual adverts when it is in the context of gift giving from a man to a woman, i.e. when the sexuality of the advert is the context of commitment. Men respond more negatively to the sexual advert when it involves gift giving as it emphasizes them having to spend money in a relationship.[45] This is in line with evolutionary theory that women value men for their resources and men value women for sex and fertility.[46] Further research found that even in men, recall of the advert is worsened by sexual content, as they focus on breasts and legs but not on the product.[47]

Cultural differences

In order to be consistent, brands use standardized campaigns across various countries.[48] Cultural differences have been found in response to sexual adverts. A 2016 study by the Korea Internet Advertising Foundation (KIAF) noted that 94.5% of South Korean high-schoolers were familiar with sex-driven ads, 83.4% of adults thought such ads have negative influence on society, and 91.2% said there are too many of such ads. A KIAF official noted that government legislation aimed to reduce such ads is not effective due to its ambiguity.[49] Research has found that sex is used in adverts more in France than in the United States because they are more sexually liberated and so receptive to its use in advertising.[50]

Prevalence

.jpg.webp)

In the 21st century, the use of increasingly explicit sexual imagery in consumer-oriented print ads have become almost commonplace. Ads for jeans, perfumes and many other products have featured provocative images that were designed to elicit sexual responses from as large a cross section of the population as possible, to shock by their ambivalence, or to appeal to repressed sexual desires, which are thought to carry a stronger emotional load. Increased tolerance, more tempered censorship, emancipatory developments and increasing buying power of previously neglected appreciative target groups in rich markets (mainly in the West) have led to a marked increase in the share of attractive flesh 'on display'.

A 2008 cross-national study examined nudity in television advertising in Brazil, Canada, China, Germany, South Korea, Thailand, and the United States. It showed that female but not male levels of nudity differed substantially across countries, and that U.S. and Chinese commercials showed the lowest level of nudity, whereas German and Thai ads showed the highest level. [51]

Historically, sex in advertising has focused on heterosexual gender roles, but there are increasing examples of sex being used to advertise to the LGBT community. The New Zealand Aids Foundation's Love Your Condom (LYC) campaign used provocative images of males alongside captions such as "Riding hard?", "Bear hunting?" and "Going deep?", followed by the hashtag #loveyourcondom.[52] It was hoped by using images explicitly directed towards homosexual men, their use of condoms would increase, which would help decrease rates of HIV transmission amongst gay and bisexual men. The campaign has been successful, with a 12% reduction in new HIV infections among MSM in New Zealand.[53]

In a 2003 study conducted at the University of Georgia’s Department of Advertising and Public Relations Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication, researchers looked at sexual advertisements in magazines over the span of the last 30 years. The rate at which sex in advertising is being used increased from 15% to 27% in the advertisements that the researchers looked at. Their reasoning behind the increase is because they believe sex still sells, specifically with “low-risk products impulse purchases.” The study also mentions “alcohol, entertainment and beauty are the main product categories that use sex in advertising.[54]

Ad Age, a magazine delivering news, analysis, and data on marketing and media, published a list of Top 100 most effective advertising of the century, out of the 100, only eight involved use of sex.[55] Unruly Media's viral video tracker lists the Top-20 most viewed car commercial viral videos; only one uses sex, while the No.1 spot was held by VW's "The Force" ad.[56] The overall top-spot (across all product segments), was held by VW's "Fun Theory" campaign, the most viewed viral video as of October 2011.

Criticism

Stereotypes

The use of sex in advertising has been criticized for its tendency to reinforce sexist stereotypes. Since the late 1970s, many researchers have determined that advertisements depict women as having less social power than men, but the ways in which women are displayed as less powerful than men have evolved over time. In modern times, advertisements have displayed women's expanding roles in the professional realm and importance in business backgrounds. However, as this change occurred there has been a substantial increase in the number of images that showcase women as less sexually powerful than men and as objects of men's desire.[57] The 2011 documentary film Miss Representation by Jennifer Siebel Newsom explores how the depiction of women in mainstream media contributes to the under-representation of women in leadership roles and other positions of influence.

Objectification

Furthermore, sex in advertising has been criticized for its emphasis on the importance of physical attractiveness and role as a mate.[58] This emphasis has led men and women to value intelligence and general skills less.[59] The rise in awareness of sexism portrayed in these types of adverts has led to stricter advertising policies. One group that enforces these rules is the Advertising Women of New York association. Adverts using highly sexual images containing nudity and unrealistic physiques can lead to self-objectification.[60] In turn, this can lead to shame, disgust, appearance anxiety, eating disorders and depression. The increase in self-objectification caused by the use of sex in advertising has been found in women and men. The latter is not surprising with the increased sexual portrayal of men in advertising.[61]

Social norms

Sex in advertising is an accepted marketing technique, however it is not unusual for it to cause backlash when it breaks social norms.[58] In 1995, the Calvin Klein advertising campaign (see section on Calvin Klein, above) that showed teenage models in provocative poses wearing Calvin Klein underwear and jeans was deemed inappropriate and shocking. The ads were withdrawn when parents and child welfare groups threatened to protest and Hudson stores did not want their stores associated with the ads. It was reported that the U.S. Justice Department was investigating the ad campaign for possible violations of federal child pornography and exploitation laws. The Justice Department subsequently decided not to prosecute Calvin Klein for these alleged violations as the DOJ “independently verified that minors were not used as models in the particular photographs that raised questions,” according to Deputy Assistant Atty. Gen. Kevin V. Di Gregory. [62]

See also

References

- 1 2 Blair, J. D., Stephenson, J. D., Hill, K. L., & Green, J. S. (2006). Ethics in advertising: sex sells, but should it?. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 9(1/2), 109.

- ↑ Rodger Streitmatter, Sex sells!: The media's journey from repression to obsession (Basic Books, 2004).

- ↑ Chism, 1999

- ↑ Tom Reichert (2002). "Sex in advertising research: A review of content, effects, and functions of sexual information in consumer advertising". Annu. Rev. Sex Res. 13: 241–73. PMID 12836733.

- ↑ Goffman, Erving (March 1, 1979). Gender Advertisements (1 ed.). Harper & Row. p. 84. ISBN 978-0060906337.

- ↑ Williams, Gareth (13 August 2015). "13 amazing adverts featuring same-sex couples". PinkNews. Retrieved 2016-11-22.

- ↑ "DOES SEX IN ADVERTISING WORK?". Branding Strategy Insider. 2008-03-22. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

- ↑ "Media influence on pre-teens and teenagers: social media, movies, YouTube and apps". Raising Children Network. Retrieved 2023-09-23.

- 1 2 3 Reichert, Tom (2011). Sex in advertising: Perspectives on the erotic appeal. Routledge. pp. 11–151.

- 1 2 Berger, Arthur Asa (2015). Ads, fads and Consumer culture (Fifth ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 99–120.

- ↑ Dahl, Sengupta & Vohs (2009)

- ↑ Zotos, Yorgos; Tsichla, Eirini (October 2014). "Snapshots of Men and Women in Interaction: An Investigation of Stereotypes in Print Advertisement Relationship Portrayals". Journal of Euromarketing. 23 (3): 35–58. doi:10.9768/0023.03.035 – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ Einav, Rabinovitch-Fox (2016). "Baby, You Can Drive My Car: Advertising Women's Freedom in 1920s America". American Journalism. 33 (4): 372–400. doi:10.1080/08821127.2016.1241641. S2CID 157498769.

- ↑ Porter, 1971

- ↑ Account Histories, 1926

- ↑ Sloan & Millman, 1979

- ↑ O'Barr, William M. (2008). "Advertising in India". Advertising & Society Review. 9 (3).

- ↑ William Mazzarella, Shoveling Smoke: Advertising and Globalization in Contemporary India (Duke University Press, 2003)

- ↑ Mark Tungate, Adland: A Global History of Advertising (2007) pp 146–49

- ↑ Sischy, Ingrid. "Vanity Fair Calvin Klein". Vanityfair.com. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- 1 2 Calvin Klein: A Case Study Archived 2012-05-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Peters, Robert. "Kiddie Porn" Controversy" Archived 2009-07-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Pulp Fiction (1994) - IMDb". IMDb.

- ↑ "Catwoman (2004) - IMDb". IMDb.

- ↑ McMurray, Jacob (2012). "Fantasy, Sci-Fi and Superheroes". In Nadoolman Landis, Deborah (ed.). Hollywood Costume. V&A Publishing. p. 290.

- ↑ Streitmatter, Roger (2004). Sex sells!: The media's journey from repression to obsession. Basic Books.

- ↑ Bowerman, Mary. "Cover up! Abercrombie & Fitch says sexual marketing is over". USA today. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- ↑ Driessen, Claire (2005). "Message Communication in Advertising: Selling the Abercrombie and Fitch Image" (PDF). UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research VIII. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- ↑ Monllos, Kristina. "Shirts on, Boys. Abercrombie Says It's Done With Sexualized Marketing". Adweek.com. Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- ↑ King, James; McClelland, Alastair; Furnham, Adrian (2015-03-01). "Sex Really Does Sell: The Recall of Sexual and Non-sexual Television Advertisements in Sexual and Non-sexual Programmes". Applied Cognitive Psychology. 29 (2): 210–216. doi:10.1002/acp.3095. ISSN 1099-0720.

- ↑ Baron, Robert S. (1982). "Sexual Content and Advertising Effectiveness: Comments on Belch Et Al. (1981) and Caccavale Et Al. (1981) by Robert S. Baron". Acr North American Advances. NA-09. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

- ↑ Anemone Cerridwen, Dean Keith Simonton (2009). "Sex Doesn't Sell—Nor Impress! Content, Box Office, Critics, and Awards in Mainstream Cinema" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-03-14.

- ↑ "Sex in ads does not sell". Emergencemarketing.com. 2005-10-25. Retrieved 2013-03-14.

- ↑ Bushman, Brad (2007). "That was a great commercial, but what were they selling? Effects of violence and sex on memory for products in television commercials". Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 37 (8): 1784–1796. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2007.00237.x. hdl:1871/39449.

- ↑ "Magazine trends study finds increase in advertisements using sex". uga.edu. 2012-06-05. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ↑ "Violence and Sex in Television Programs Do Not Sell Products in Advertisements". 2012-06-05. Retrieved 2012-06-05.

- ↑ Szabo, Lisa (30 October 2012). "Sexy breast cancer campaigns anger many patients". USA Today. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- ↑ Vargas-Bianchi, Lizardo; Mensa, Marta (2020-03-21). "Do you remember me? Women sexual objectification in advertising among young consumers". Young Consumers. 21 (1): 77–90. doi:10.1108/YC-04-2019-0994. ISSN 1747-3616. S2CID 216353566.

- ↑ "Women find sexually explicit ads unappealing—unless the price is right". medicalxpress.com. 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

- ↑ Soley, Lawrence (1986). "Sex in Advertising: A Comparison of 1964 and 1984 Magazine Advertisements". Journal of Advertising. 15 (3): 46–64. doi:10.1080/00913367.1986.10673018.

- ↑ "Sex doesn't sell? This study into women's response to raunchy advertising starts wrong and gets worse". www.independent.co.uk. 2013-12-10. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- ↑ "Study: Does sex always sell?". phys.org. 2013-12-19. Retrieved 2013-12-19.

- ↑ Sengupta, J (2008). "Gender-related reactions to gratuitous sex appeals in advertising". Journal of Consumer Advertising. 18: 62–78. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2007.10.010.

- ↑ Herold (1993). "Gender differences in casual sex and AIDS prevention: A survey of dating bars". Journal of Sex Research. 30: 36–42. doi:10.1080/00224499309551676.

- ↑ Dahl, Darren (2009). "Sex in advertising: Gender differences and the role of relationship commitment". Journal of Consumer Research. 36 (2): 215–231. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.620.2353. doi:10.1086/597158.

- ↑ Buss, David (1989). "Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 12: 1–14. doi:10.1017/s0140525x00023992.

- ↑ Nudd (2005). "Does sex really sell?". Adweek. 46: 14–17.

- ↑ Argawal, Wadhu (1995). "Review of a 40-year debate in international advertising: Practitioner and academician perspectives to the standardization/adaptation issue". International Marketing Review. 12: 26–48. doi:10.1108/02651339510080089.

- ↑ "Internet Ads with Sexual Imagery at a Critical Level: Survey | Be Korea-savvy". koreabizwire.com. 8 September 2016. Retrieved 2016-09-12.

- ↑ Biswas (1992). "A comparison of print advertisements from the United States and France". Journal of Advertising. 21 (4): 73–81. doi:10.1080/00913367.1992.10673387.

- ↑ Nelson, Michelle R.; Paek, Hye-Jin (2008). "Nudity of female and male models in primetime TV advertising across seven countries". International Journal of Advertising. 27 (5): 715–744. doi:10.2501/s0265048708080281. S2CID 144322217.

- ↑ "Order free condoms". New Zealand Aids Foundation. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ "History of NZAF". New Zealand Aids Foundation. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ↑ "Why Sex Sells…More Than Ever". Business News Daily. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ↑ Garfield, Bob (29 March 1999). "Top 100 Advertising Campaigns of the Century". Ad Age. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

- ↑ "Top-20 most popular car commercials". Unruly Media. Archived from the original on 2014-08-11. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

- ↑ Stankiewicz and Rosselli, Julie and Francine (2008). "Women as Sex Objects and Victims in Print Advertisements". Sex Roles. 58 (7): 579–589. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9359-1. S2CID 143452062.

- 1 2 Timke, Edward; O'Barr, William M.; Zuzarte, Raquelle M.; Reichert, Tom; Mechlin, David; Lambiase, Jacqueline; Kilbourne, Jean; Bronstein, Carolyn; Bass, Debra (2018). "Roundtable on Sex in Advertising, Part I". Advertising & Society Quarterly. 19 (4). doi:10.1353/asr.2018.0034. ISSN 2475-1790. S2CID 149832346.

- ↑ Pardun, Carol (2013). Advertising and Society.

- ↑ Roberts (2004). "Mere exposure:effects of priming a state of self-objectification". Sex Roles. 51: 17–28. doi:10.1023/b:sers.0000032306.20462.22. S2CID 55703429.

- ↑ Reichart, Tom (1999). "Cheesecake and beefcake: No matter how you slice it, sexual explicitness in advertising continues to increase". Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 76: 7–20. doi:10.1177/107769909907600102. S2CID 145780411.

- ↑ "Justice Department Plans No Charges Over Calvin Klein Ads". Los Angeles Times. 1995-11-16. Retrieved 2015-03-31.

Further reading

- Garcia, Eli, and Kenneth CC Yang. "Consumer responses to sexual appeals in cross-cultural advertisements." Journal of International Consumer Marketing 19#2 (2006): 29–52.

- Reichert, Tom, and Jacqueline Lambiase, eds. Sex in advertising: Perspectives on the erotic appeal (Routledge, 2014)

- Sherman, Claire, and Pascale Quester. "The influence of product/nudity congruence on advertising effectiveness." Journal of Promotion Management 11#2-3 (2006): 61–89.

- Streitmatter, Roger. Sex sells!: The media's journey from repression to obsession (Basic Books, 2004)

External links

Media related to Sex in advertising at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sex in advertising at Wikimedia Commons