Serres

Σέρρες | |

|---|---|

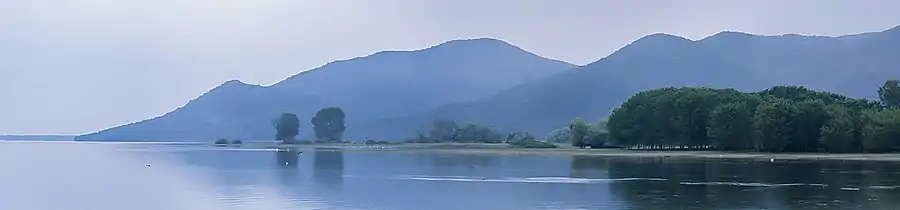

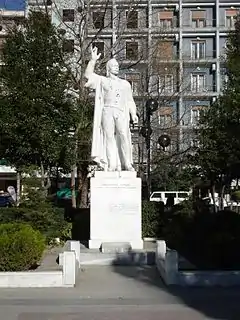

Clockwise from top: Saints Theodoroi Church, Serres Acropolis, Serres Prefecture Building, Archaeological Museum of Serres, Lake Kerkini, Emmanouel Pappas Statue and Sarakatsani Folklore Museum | |

Seal | |

Serres Location within the region  | |

| Coordinates: 41°5′N 23°33′E / 41.083°N 23.550°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Geographic region | Macedonia |

| Administrative region | Central Macedonia |

| Regional unit | Serres |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Varvara Mitliagka |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 600.5 km2 (231.9 sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 253.0 km2 (97.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 50 m (160 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

| • Municipality | 74.004 |

| • Municipality density | 0.12/km2 (0.32/sq mi) |

| • Municipal unit | 60.888 |

| • Municipal unit density | 0.24/km2 (0.62/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Serrean (Greek:Serreos) |

| Community | |

| • Population | 59.260 (2021) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 621 xx |

| Area code(s) | (+30) 2321x |

| Vehicle registration | ΕΡx-xxxx |

| Website | www.serres.gr |

Sérres (Greek: Σέρρες [ˈseɾes] ⓘ) is a city in Macedonia, Greece, capital of the Serres regional unit and third largest city in the region of Central Macedonia, after Thessaloniki and Katerini.

Serres is one of the administrative and economic centers of Northern Greece. The city is situated in a fertile plain at an elevation of about 70 metres (230 feet), some 24 kilometres (15 miles) northeast of the Strymon river and 69 km (43 mi) north-east of Thessaloniki, respectively. Serres' official municipal population was 74.004 in 2021.

The city is home to the Department of Physical Education and Sport Science of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greek: Τ.Ε.Φ.Α.Α. Σερρών) and the Serres Campus of the International Hellenic University (former "Technological Educational Institute of Central Macedonia"), composed of the Faculty of Engineering, the Faculty of Economics and Management, and the Department of Interior Architecture and Design. The head of the Faculty of Engineering of the International Hellenic University is located in Serres.

Names

The Ancient Greek historian Herodotus mentions the city as Siris (Σίρις) in the 5th century BC. Theopompus refers to the city as Sirra (Σίρρα). Later, it is mentioned as Sirae, in the plural, by the Roman historian Livy. Since then the name of the city has remained plural and by the 5th century AD it was already in the contemporary form as Serrae or Sérrai (Σέρραι) (plural), which remained the Katharevousa form for the name till modern times. In the local Greek dialect, the city is still known as "ta Serras" (τα Σέρρας), which is actually a corruption of the plural accusative "tas Serras" (τας Σέρρας) of the archaic form "Serrae".[1] The oldest mention of this form is attested in a document of the Docheiariou Monastery in Mount Athos from 1383, while there are many other such references in documents from the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. It was known as Serez or Siroz in Turkish. In the Slavic languages, the city is known as Ser (Сер) in Serbian, while in Bulgarian it is known as Syar (Сяр) or Ser (Сер). In Aromanian, Serres is known as Siar or Nsiar.[2]

History

Antiquity

Although the earliest mention of Serres (as Siris) is dating in the 5th century BC (Herodotus), the city was founded long before the Trojan War, probably at the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC. The ancient city was built on a high and steep hill (known as "Koulas") just north of Serres.[3] It held a strategic position, since it controlled a land road that followed the valley of the river Strymon from the shores of Strymonian Gulf to the Danubian countries.

The most ancient known inhabitants of the area were the Bryges (Phrygians) and Strymonians. Afterwards were the Paeonian tribes of the Siropaiones[4] (since 1100 BC) and Odomantes (from the early 5th century BC until the end of antiquity).[5] These populations mainly engaged in agriculture and cattle-raising especially worshiped the Sun, the deified river Strymon and later the "Thracian horseman".[6]

The ancient city of Serraepolis was founded in Cilicia by Siropaiones exiled from Serres.

Roman era

During the Roman period (168 BC – 315 AD) the city is mentioned in sources under the name Sirra (Σίρρα) and in inscriptions as Sirraion polis (Σιρραίων πόλις, lit. '"city of the Sirraians"').[7] It was an important city of the Roman province of Macedonia, with the status of a civitas stipendaria. It flourished especially during the imperial period thanks to the Pax Romana. Then, during the great crisis of the Roman Empire (235–284 AD), the city declined and only in the times of Diocletian, with its reforms (Tetrarchic system), returned to prosperity.[8]

As regards the urban structure it featured, like all Greek cities, a market (agora), parliament (bouleuterion), theater, gymnasium and temples. As we know from epigraphic evidence, the local government was also based on the known Greek institutions, which were the parliament (boule), the citizen body (demos) and the archons (politarchai, agoranomoi, gymnasiarchai, high priests etc.).[9] It was also the seat of a federation of five cities ("Pentapolis") and actively participated in the provincial life and organization of the Macedonians; while many residents, mostly members of the local aristocracy, had received the right of Roman citizenship and were promoted to senior provincial dignities.[10]

As a city-state (polis), apart from the usual Greek institutions, Sirra also had its own territory (chora), which roughly coincided with the area of the modern province of Serres. The organization of its territory was based on villages (komai, sing. kome), whose many sites have been found in various places near modern villages, such as Lefkonas, Oreini, Ano Vrontou, Neo Souli, Agio Pnevma, Chryso, Paralimnio etc. Within the limits of its territory have also discovered traces of marble quarries and iron mines, which indicate systematic exploitation of the existing mineral wealth in the imperial period (1st to 3rd century AD).[11]

In terms of population, except the most numerous Greek element, are recognized some population substrates even from prehistoric times. Concerning the society, the main feature was its distinction in upper (rich) and lower (poor) social strata (honestiores and humiliores in Latin). Finally, concerning the cults of the residents, except the known panhellenic cults (Dionysus, Zeus, Dioscuri, Apollo, Asclepius, Artemis and Isis),[12] are evidenced and some local and Thracian cults as the Thracian horseman (or "Hero").[13]

Many inscriptions of Roman (imperial) times have been found in the city (and to the early 1960s in the surrounding area). From these inscriptions (almost all written in Greek and only three in Latin), the eight are votive or honorific[14] and all other on epitaph reliefs or steles.[15]

Middle Ages

The first attested bishop of the city is recorded as participating in the Second Council of Ephesus in 449.[16]

In c. 803 Emperor Nikephoros I rebuilt the town and installed a strong garrison against the Slavic tribes of the Balkans.[17] The city's history was uneventful until the 10th century, being in the heartland of the Byzantine Greek world,[16] until it was pillaged and briefly occupied by the Bulgarians.[16] In 1185, the environs of the city were pillaged by a Norman invasion, and in the Battle of Serres in 1195/6 the Byzantines were defeated by the rebellious Bulgarian ruler Ivan Asen I.[16] After the Fourth Crusade, Boniface of Montferrat took over the city, but shortly after Kaloyan of Bulgaria defeated the Crusaders of the Latin Empire and captured the city, until it was retaken by the Crusaders in the early 1230s.[16] According to George Akropolites, Kaloyan almost destroyed the city, reducing it from a sizeable urban centre to a small settlement clustered around the fortified citadel, while the lower town was protected by a weak stone wall.[16]

The city returned to Byzantine rule in 1246, when it was captured by the Nicaean Empire. By the 14th century, the city had regained its former size and prosperity, so that Nikephoros Gregoras called it a "large and marvelous" city.[16] Taking advantage of the Byzantine civil war of 1341–47, the Serbs besieged and took the city on 25 September 1345. It became the capital of Stefan Dušan's Serbian Empire.[16] Dušan rebuilt the citadel for the last time.[17] After Dušan's death in 1355 his realm fell into feudal anarchy, and Serres became a separate principality, initially under Dushan's Empress-dowager Helena and after 1365 by the Despot Jovan Uglješa.[16] Jovan Uglješa maintained close political and cultural ties to the Byzantine court in Constantinople, and the Greek element rose again to prominence: local Greeks played a major role in his administration, which was carried out in the Greek language.[16] After the 1371 Battle of Maritsa, the Byzantines under Manuel II Palaiologos (then governor of Thessalonica) retook Serres.[16]

Ottoman period

Serres fell to the Ottoman Empire for the first time briefly in 1371,[17] and definitely on 19 September 1383—although the Ottoman sources give several earlier and contradictory dates, the date is securely established by multiple Greek sources.[18]

The city (Siroz in Turkish) and the surrounding region became a fief of Evrenos Beg, who brought in Yörük settlers from Sarukhan.[18] Oral sources report that the terms of surrender guaranteed to the Greek population possession of its city quarters and churches, while the Turks were to settle outside the Byzantine walls, which were soon demolished to prevent any rebellion. The new Turkish quarters were established to the west and south of the walls, and named after their military leaders.[17] The Grand Vizier Çandarlı Kara Halil Hayreddin Pasha built the town's first mosque, the Old Mosque (Eski Camii), now destroyed, in 1385, as well as the Old Baths (Eski Hammam).[17] In the same year, Sultan Murad I used the city as a base for operations against the Serbs.[17] During the Ottoman Interregnum, the rebel Sheikh Bedreddin was executed in the city in 1412.[17] Although never rising to particular prominence within the Ottoman Empire, Serres became the site of a mint from 1413/14 on.[18]

In 1454/55, the city is estimated to have had some 6,200 inhabitants.[17] The Muslim population grew steadily, and in the 15th century there were 25 Muslim to 45 Christian quarters.[17] Towards the end of the 15th century, the first Sephardi Jews arrived from Sicily and Spain,[17] and the Grand Vizier Koca Mustafa Pasha funded various public and charitable buildings in the city.[17] In the early 16th century, Serres was visited by the French traveller Pierre Belon, who reported that the town was mainly inhabited by Greeks alongside German and Sephardi communities, while the people in the surrounding country spoke Greek and Bulgarian.[18] In 1519 (Hijri 925) the town had 684 Muslim and 545 Non-Muslim households 54 of which being Jewish households; it was a has of the Sultan.[19] In the aftermath of the Christian victory at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, Turkish reprisals were directed at the Greek population, who had risen in revolt.[17] The metropolitan cathedral of Serres was looted along with seven other churches, while land and land titles owned by the Monastery of St John the Baptist were confiscated.[20]

Much information on the town's history in the years 1598–1642 is given by the chronicle of the priest Synadinos, a former merchant who became a priest.[17] The town is also described in some detail by the 17th-century Ottoman travellers Haji Khalifa and Evliya Çelebi, as well as the Capuchin friar Robert de Dreux.[17] Evliya records a prosperous settlement, comprising the 10 Christian quarters of the old town, and 30 Muslim quarters in the new town, with about 2,000 and 4,000 houses respectively, 12 main mosques and 91 smaller ones, 26 madrasahs, two tekkes and five baths.[17] It boasted a large market, among the most important in the region of Macedonia, with 2,000 shops and 17 khans.[17]

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, Serres was an autonomous lordship (beylik) under a succession of derebeys, within the Sanjak of Salonica.[18][21] At the end of the 18th century, Serres was a cotton-producing area, exporting 50,000 balls of cotton to Germany, France, Venice and Livorno.[22] The metropolitan bishop Gabriel founded in 1735 the Greek School of Serres, which he directed until 1745. The school was maintained by donations from wealthy Greek merchants, among them Ioannes Constas from Vienna with 10,800 florins and the banker and tragic leader of the Greek War of Independence in Macedonia Emmanouil Pappas, who donated 1,000 Turkish silver coins. Minas Minoides taught philosophy and grammar in 1815–19. The school operated also in the period of the Greek War of Independence under Argyrios Paparizou from Siatista.[23]

A great fire in 1849 destroyed most of the city's 31 surviving churches.[17] Serres became a regular province c. 1846 as the Sanjak of Siroz of the Salonica Eyalet (later Salonica Vilayet).[21] In the late 19th century, the kaza of Serres had a total population of 83.499, consisting of 31.210 Muslims, 31.148 Greeks, 19.494 Bulgarians, 995 Jews, 5 Armenians and 647 foreign citizens, and ranked, along with Monastir and Salonica, as one of the most important towns in Macedonia.[17][24]

The development of railways, highways and sea transport by steamship diminished the importance of the annual fairs for which the city was famous, and commercial activity declined in the late 19th century.[17] In 1886, the Greek colonel N. Schinas described the city as having 28,000 inhabitants, 26 churches and 22 mosques, two Greek and six Turkish schools, 24 khans and an enclosed market.[17] The city recovered some of its importance when it was connected via railway to Salonica and Constantinople in 1896.[17] During the last decades of Ottoman rule, the once dominant cultivation of cotton was replaced by tobacco.[17]

In the early 20th century, the city became a focus of anti-Ottoman unrest, which resulted in the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising of 1903.

The Ottoman census of 1905 registered 42,000 inhabitants.[17]

Modern period

A Bulgarian army commanded by General Georgi Todorov captured Serres during the First Balkan War on November 6, 1912, but was forced to withdraw by Greek forces commanded by the King of Greece, Constantine I, during the Second Balkan War. The first officer of the Hellenic Army to enter Serres was infantry colonel Napoleon Sotilis, head of the 7th Infantry Regiment on July 11, 1913.

Prior to abandoning the city, the Bulgarians set fire to it, which burned down much of the old Byzantine town, as well as many of the newer Muslim quarters.[17] As the National Schism erupted in Greece during the First World War, Serres was temporarily occupied by the Central Powers after King Constantine ordered the local garrison not to resist to a token force of the Imperial German Army; eventually the city was liberated in 1917 by Greek-French Entente forces under the Venizelos government.

During the Second World War, after the conquest of mainland Greece by Nazi Germany in April 1941 (which was followed by the conquest of Crete in June), Serres was assigned by the Nazis to their Bulgarian allies (along with the rest of East Macedonia and Thrace and the island of Thasos), who occupied the city until the Allied liberation of Greece in 1944.[25] In 1943, Serres' Jewish population was deported by the Gestapo to the Treblinka death camp and exterminated. There was a significant resistance movement in the city during the occupation, led by the left-wing National Liberation Front (EAM).[26]

In the postwar years, the city's population grew substantially, and there was also a significant rise in the standard of living. The long-serving conservative Greek Prime Minister Constantine Karamanlis (in office from 1955 to 1963 and again from 1974 to 1980) was a native of Serres, and as a result its people could count on the support of the central Greek government in Athens. However, the villages in the plains around the city were not so lucky; the low prices of agricultural products led many people of these villages to emigrate, mostly to the United States and West Germany.

As of 2015, the Mayor of Serres is Petros Angelidis (independent, formerly a member of PASOK).

Municipality

The present Serres municipality was formed at the 2011 local government reform by the merger of the following 6 former municipalities, that became municipal units of the new municipality: Ano Vrontou, Kapetan Mitrousi, Lefkonas, Oreini, Serres, and Skoutari.[27]

The municipality has an area of 600.479 km2, the municipal unit 252.973 km2.[28]

Climate

Serres has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa) bordering on a cold semi-arid climate (BSk). Serres has an irregular precipitation pattern throughout the year, with no pronounced dry season, although rainfall is fairly light year round. Summers are hot, whereas winters are cool but rarely very cold and snowy.

| Climate data for Serres (1971–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.9 (67.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

30.3 (86.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.2 (90.0) |

27.9 (82.2) |

21.5 (70.7) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.1 (48.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

6.4 (43.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.6 (76.3) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

21.7 (71.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

5.2 (41.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.9 (55.2) |

16.9 (62.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

4.9 (40.8) |

1.2 (34.2) |

9.2 (48.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 34.6 (1.36) |

37.7 (1.48) |

32.6 (1.28) |

38.5 (1.52) |

47.3 (1.86) |

40.7 (1.60) |

27.6 (1.09) |

26.8 (1.06) |

29.1 (1.15) |

43.0 (1.69) |

48.8 (1.92) |

55.4 (2.18) |

464.2 (18.28) |

| Average precipitation days | 7.9 | 8.0 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 9.7 | 7.1 | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 6.5 | 8.2 | 9.3 | 89.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77.1 | 71.7 | 68.1 | 63.2 | 59.8 | 53.8 | 51.7 | 54.5 | 59.5 | 69.6 | 76.8 | 80.2 | 65.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 98.4 | 111.4 | 147.4 | 191.6 | 237.5 | 293.9 | 316.5 | 294.7 | 236.3 | 169.0 | 106.8 | 85.9 | 2,289.4 |

| Source: Hellenic National Meteorological Service[29] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Serres is the capital of a primarily agricultural district and is an important trade centre for tobacco, grain, and livestock. Following the development of a government-sponsored manufacturing area in the late 20th century, it has also become a centre for the production of textiles and other manufactured items. Various products, meat and dairy, are also produced by breeding at Lake Kerkini.

Places of interest

- Serres Public Regional Theatre

- Archaeological Museum of Serres (in the Ottoman bezesten)

- Serres Ecclesiastical Museum

- Sarakatsani Folklore Museum

- Lake Kerkini near the town

- Mehmet Bey Mosque

- Hadzilia Folklore and Ethnological Museum

- Serres Racing Circuit

- Saints Theodore Tyro and Theodore Stratelates Church, Serres

Culture

Late Ottoman author Omer Seyfeddin set his fictional work White Tulip (Beyaz Lale) describing events during the First Balkan War in the town.[30][31]

Cuisine

Probably the most well-known food from Serres is bougatsa. Additionally, gyros and souvlaki are standard forms of Greek cuisine served in many restaurants and taverns. One delicacy that is truly unique to the region is Akanés, which is a type of gourmet candy delight prepared according to a secret recipe since the beginning of the 20th century by the Roumbos family. Allegedly, Aristeidis Roumbos, the confectioner who invented this candy, disclosed the recipe to one of his loyal trainees, who then proceeded to establish a rival akanes business. Nevertheless, the Roumbos family, to this day, continues to produce this delight in their quaint workshop, which is reminiscent of life in the 1950s. Another popular dessert of the area is Poniró, similar to sfogliatella.

Neighborhoods

- Katakonozi is one of the most prosperous neighborhoods of the city, and it is currently experiencing a real estate growth.

- Kamenikia is one historic western neighborhood of the city.

- Taxiarches (Center)

- Kallithea

- Agios Panteleimon

- Agios Antonios

- Kiouplia

- Omonoia - Kalyvia

- Agios Nikitas

- Ionia (Sfageia)

- Saranta Martyres

- Profitis Ilias

- Siris (Sigis / Nea Kifisia)

- Agioi Anargyroi

- Timiou Stavrou

- Agios Athanasios

- Makedonomachon

- Vyzantio (Kalkani)

Transport

Road

![]() E79 passes near the city, connecting the city with Thessaloniki and the Greek-Bulgarian border of Promachonas.

E79 passes near the city, connecting the city with Thessaloniki and the Greek-Bulgarian border of Promachonas.

The Urban KTEL of Serres (has undertaken the transport within the city, while the Intercity KTEL of Serres connects the city with other cities of Macedonia and the rest of Greece.

Rail

Outside the city the railway station is located, on the Thessaloniki-Alexandroupoli Line, with local and regional services to Thessaloniki and Alexandroupolis.

Population

| Year | Municipal unit | Municipality |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 46,317 | – |

| 1991 | 49,830 | – |

| 2001 | 56,145 | – |

| 2011 | 58,287 | – |

| 2021 | 60.888 | 74.004 |

Notable residents

- Christos Aritzis (born 1984), footballer

- Gazi Husrev-beg (1480–1541), bey in the Ottoman Empire

- Halil Rifat Pasha, 19th-century Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire

- Hoca Ibrahim Pasha, Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire in 1713

- Emmanouel Pappas, leader of the Greek War of Independence in Macedonia

- Konstantinos Karamanlis (8 March 1907 – 23 April 1998), founder and leader of ERE (Ethniki Rizospastike Enosis) and founder of New Democracy party, four times Prime Minister of Greece, the 3rd and 5th President of the Third Hellenic Republic, was born in Proti Serron, a village near Serres

- Efstathios Tavlaridis, football player

- Doukas Gaitatzis, chieftain of the Macedonian Struggle

- Demetrius Hondros, physicist

- Vicky Kalogera (1971), astrophysicist, Professor at Northwestern University and Director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA)

- Giorgos Kapoutzidis (1972), scriptwriter and actor

- Glykeria, singer

- Stratos Dionysiou (1935–1990), singer

- Angelos Charisteas, football player

- Maria Houkli, journalist

- Anna Spyridopoulou, basketball player

- Kostas Tsimikas, football player

- Christos Xenitopoulos, football player

- Dimitrios Psaltis (1970), astrophysicist, Professor of Astronomy and Physics at the University of Arizona

- Panos Ipeirotis, computer scientist, Professor of Information, Operations and Management Sciences at NYU Stern

Motor Sports

The City of Serres attracts high attention for motor sports. In the city is the Serres Circuit. It was built in 1998 in accordance with the construction requirements of up to Formula 3 races.[32] The racetrack is the largest in Greece and meets the construction specifications of the International Automobile Federation and of the International Motorcycling Federation. It is a municipal corporation with majority shareholder the Municipality of Serres.

Higher education

In the city of Serres there is the Technological Educational Institution (TEI) of Central Macedonia. It has more than 14.000 bachelor and master students, also three faculties and even more departments. In autumn 2012 there operated (for first time) two master programmes in English (MBA, MSc) and in 2013 a third one was added (MSc). In 2019 the Technological Educational Institution (TEI) of Central Macedonia merged with the International Hellenic University.

There is also a Department of Physical Education and Sport Science of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki that operates in the city of Serres, offering bachelor's and master's degrees.

In addition, in the Vocational Training Institute (Greek: Ι.Ε.Κ.) of Serres, various specialisations are being taught in programmes that last for up to two years of study.

Sporting teams

Serres hosts the sport club Panserraikos, a football club that plays in second national division (football league 2),[33]

| Club | Founded | Sports | Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panserraikos | 1964 | Football | Earlier presence in A Ethniki |

International relations

Twin towns — sister cities

Serres is twinned with:

Gallery

View of the center

View of the center Sts Cosmas and Damian church (1817)

Sts Cosmas and Damian church (1817) Evangelical church of Serres

Evangelical church of Serres St John Baptist church

St John Baptist church

Fresco in Prodromou Monastery near Serres, depicting Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos presenting to the monastery some privileges

Fresco in Prodromou Monastery near Serres, depicting Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos presenting to the monastery some privileges Buffalos breeding, Lake Kerkini

Buffalos breeding, Lake Kerkini Serrai sheep breed

Serrai sheep breed

References

- "Sérrai." Encyclopædia Britannica, 2006.

- "Sérrai, Siris, or Serres." The Columbia Encyclopedia, 2004.

- ↑ https://www.serres.gr/index.php/istoria/praktika-diethnon-epistimonikon-synedrion-serron-2/istoria-serron-samsaris Archived 2018-06-24 at the Wayback Machine Dimitrios C. Samsaris, A history of Serres (in the Ancient and Roman times), Thessaloniki 1999, p. 9-14 (Website of Municipality of Serres)

- ↑ The War of Numbers and its First Victim: The Aromanians in Macedonia (End of 19th – Beginning of 20th century)

- ↑ https://www.serres.gr/index.php/istoria/praktika-diethnon-epistimonikon-synedrion-serron-2/istoria-serron-samsaris Archived 2018-06-24 at the Wayback Machine Dimitrios C. Samsaris, A History of Serres (in the Ancient and Roman Times) (in Greek), Thessaloniki 1999, p. 48 (Website of Municipality of Serres)

- ↑ Dimitrios C. Samsaris, Les Péoniens dans la vallée du Bas-Strymon, Klio 64(1982), 2, p. 339-351

- ↑ Dimitrios C. Samsaris, Les Thraces dans l’ Empire romain d’ Orient (Le territoire de la Grèce actuelle). Etude ethno-démographique, sociale, prosopographique et anthroponymique, Jannina (Université) 1993, p. 36, 372 et passim

- ↑ https://www.serres.gr/index.php/istoria/praktika-diethnon-epistimonikon-synedrion-serron-2/istoria-serron-samsaris Archived 2018-06-24 at the Wayback Machine Dimitrios C. Samsaris, A history of Serres (in the Ancient and Roman times), Thessaloniki 1999, p. 27-46, 69–71, 83–96 (Website of Municipality of Serres)

- ↑ Dimitrios C. Samsaris, La vallée du Bas-Strymon á l’ époque impériale (Contribution épigraphique á la topographie, l' onomastique, l' histoire et aux cultes de la province romaine de Macédoine), Dodona 18 (1989), fasc. 1, p. 235, n. 37 = The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 37, # PH150675)

- ↑ https://www.serres.gr/index.php/istoria/praktika-diethnon-epistimonikon-synedrion-serron-2/istoria-serron-samsaris Archived 2018-06-24 at the Wayback Machine Dimitrios C. Samsaris, A History of Serres, p. 97-113 (Website of Municipality of Serres)

- ↑ Dimitrios C. Samsaris, La vallée du Bas-Strymon á l’ époque impériale (Contribution épigraphique á la topographie, l’ onomastique, l’ histoire et aux cultes de la province romaine de Macédoine), Dodona 18 (1989), fasc. 1, p. 235-236, n. 37-38 = The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 37, # PH150675)The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 38, # PH150676)

- ↑ https://www.serres.gr/index.php/istoria/praktika-diethnon-epistimonikon-synedrion-serron-2/istoria-serron-samsaris Archived 2018-06-24 at the Wayback Machine Dimitrios C. Samsaris, A history of Serres (in the Ancient and Roman times), p. 9-13, 97–125, 186–188 (Website of Municipality of Serres) == Dimitrios C. Samsaris, Individual grants of the Roman citizenship (civitas Romana) and its propagation in the Roman province of Macedonia, III. The eastern part of the province (in Greek), Makedonika 28(1991–92)156–196

- ↑ Dimitrios C. Samsaris, Les mines et la metallurgie de fer et de cuivre dans la province romaine de Macédoine, Klio 69(1987), 1, p. 154, 156-157

- ↑ https://www.serres.gr/index.php/istoria/praktika-diethnon-epistimonikon-synedrion-serron-2/istoria-serron-samsaris Archived 2018-06-24 at the Wayback Machine Dimitrios C. Samsaris, A history of Serres, p. 137-175, 213–254 (Website of Municipality of Serres)

- ↑ Dimitrios C. Samsaris, Le culte du Cavalier thrace dans la vallée du Bas-Strymon à l’ époque romaine (Recherches pour la localisation de ses sanctuaries), Dritter Internationaler Thrakologischer Kongress (2-6 Juni 1980, Wien), II, Sofia 1984, p. 284-289 == D. C. Samsaris, Recherches sur l’ histoire, la topographie et les cultes des provinces romaines de Macédoine et de Thrace (en grec), Thessalonique 1984, p. 43-58

- ↑ Dimitrios C. Samsaris, La vallée du Bas-Strymon á l’ époque impériale (Contribution épigraphique á la topographie, l’ onomastique, l’ histoire et aux cultes de la province romaine de Macédoine), Dodona 18 (1989), fasc. 1, p. 232-240, n. 35-42 = The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 35, # PH150672)The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 36, # PH150673)The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 36(1), # PH150674)The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 37, # PH150675)The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 38, # PH150676)The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 39, # PH150677)The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 40, # PH150678) The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 41, # PH150679)The Packard Humanities Institute (Samsaris, Bas-Strymon 42, # PH150680)

- ↑ Dimitrios C. Samsaris, La vallée du Bas-Strymon á l’ époque impériale (Contribution épigraphique á la topographie, l’ onomastique, l’ histoire et aux cultes de la province romaine de Macédoine), Dodona 18 (1989), fasc. 1, p. 241-262, n. 43-89

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Gregory, Timothy E.; Ševčenko, Nancy Patterson (1991). "Serres". In Kazhdan, Alexander (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1881–1882. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Yerolimpos, Alexandra (1997). "Siroz". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume IX: San–Sze (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 673–675. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor, ed. (1987). "Serres". E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume VII: S–Ṭaiba. Leiden: BRILL. p. 234. ISBN 90-04-08265-4.

- ↑ GÖKBİLGİN, M. TAYYİB (1956). "KANUNÎ SULTAN SÜLEYMAN DEVRİ BAŞLARINDA RUMELİ EYALETİ, LİVALARI, ŞEHİR VE KASABALARI". Belleten. 20 (78): 265. eISSN 2791-6472. ISSN 0041-4255.

- ↑ Vakalopoulos, Constantinos A. (1996). Ιστορία του Βορείου Ελληνισμού -Μακεδονία. Εκδοτικός Οίκος Αδελφών Κυριακίδη. p. 80. ISBN 960-343-017-X.

The metropolis of Serres was looted along with seven other churches, the Monastery of St John the Baptist, while land owned by the monastery was confiscated.

- 1 2 Birken, Andreas (1976). Die Provinzen des Osmanischen Reiches. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients (in German). Vol. 13. Reichert. p. 77. ISBN 978-3-920153-56-8.

- ↑ Vakalopoulos, Constantinos A. (1996). Ιστορία του Βορείου Ελληνισμού -Μακεδονία. Εκδοτικός Οίκος Αδελφών Κυριακίδη. p. 130. ISBN 960-343-017-X.

At the end of the 18th C, Serres was cotton producing area, exporting 50,000 balls of cotton to Germany, France, Venice and Livorno.

- ↑ Vakalopoulos, Constantinos A. (1996). Ιστορία του Βορείου Ελληνισμού -Μακεδονία. Εκδοτικός Οίκος Αδελφών Κυριακίδη. pp. 131–132. ISBN 960-343-017-X.

- ↑ Kemal Karpat (1985), Ottoman Population, 1830-1914, Demographic and Social Characteristics, The University of Wisconsin Press, p. 136-137

- ↑ Tsekou, Katerina (14 October 2011). "Η Βόρεια Ελλάδα υπό Βουλγαρική κατοχή 1941 (Northern Greece under Bulgarian Occupation, 1941)".

- ↑ ΑΠΟΜΝΗΜΟΝΕΥΤΙΚΕΣ ΣΗΜΕΙΩΣΕΙΣ Γ. ΚΟΚΚΙΝΟΥ, Γραμματέα ΕΑΜ Ν. Σερρών, για την αντίσταση στη Βουλγαρική κατοχή του 1941–44,

- ↑ "ΦΕΚ A 87/2010, Kallikratis reform law text" (in Greek). Government Gazette.

- ↑ "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece.

- ↑ "Serres Climatological data 1971–2010". Hellenic National Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ Boyar, Ebru (29 June 2007). Ottomans, Turks and the Balkans: Empire Lost, Relations Altered. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857715432 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Koroglu, Erol (21 July 2007). Ottoman Propaganda and Turkish Identity: Literature in Turkey During World War I. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9780857715371 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Racetrack • Serres Racing Circuit • RDE • Rent Drive Enjoy".

- ↑ "Athletics Land". panserraikos.gr.

- ↑ "Twinnings" (PDF). Central Union of Municipalities & Communities of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-06-30. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

External links

- Information about Serres (in English and Greek)

- Information about Serres by the Municipality of Serres (in Greek)

- Awarded "EDEN – European Destinations of Excellence" non traditional tourist destination 2010

- The deportation of the Jews of Serres to the Treblinka extermination camp during World War II, at Yad Vashem website.