| Jaguar | |

|---|---|

| |

| A French Air Force Jaguar completes air-to-air refueling over the Adriatic Sea | |

| Role | Attack aircraft |

| National origin | France/United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | SEPECAT (Breguet/BAC) |

| Built by | Hindustan Aeronautics Limited |

| First flight | 8 September 1968 |

| Introduction | 1973 |

| Retired | 2005 (France) / 2007 (UK) / 2014 (Oman) |

| Status | In service with Indian Air Force |

| Primary users | Indian Air Force

|

| Produced | 1968–1981 |

| Number built | 573[1] |

The SEPECAT Jaguar is an Anglo-French jet attack aircraft originally used by the British Royal Air Force and the French Air Force in the close air support and nuclear strike role. It is still in service with the Indian Air Force.

Originally conceived in the 1960s as a jet trainer with a light ground attack capability, the requirement for the aircraft soon changed to include supersonic performance, reconnaissance and tactical nuclear strike roles. A carrier-based variant was also planned for French Navy service, but this was cancelled in favour of the cheaper, fully French-built Dassault-Breguet Super Étendard. The aircraft were manufactured by SEPECAT (Société Européenne de Production de l'avion Ecole de Combat et d'Appui Tactique), a joint venture between Breguet and the British Aircraft Corporation, one of the first major joint Anglo-French military aircraft programmes.

The Jaguar was exported to India, Oman, Ecuador and Nigeria. The aircraft was used in numerous conflicts and military operations in Mauritania, Chad, Iraq, Bosnia, and Pakistan, as well as providing a ready nuclear delivery platform for the United Kingdom, France, and India throughout the latter half of the Cold War and beyond. In the Gulf War, the Jaguar was praised for its reliability and was a valuable coalition resource. The aircraft served with the French Air Force as the main strike/attack aircraft until 1 July 2005, and with the Royal Air Force until the end of April 2007. Its role was replaced by the Eurofighter Typhoon in the RAF and the Dassault Rafale in the French Air Force.

Development

Background

The Jaguar programme began in the early 1960s, in response to a British requirement (Air Staff Target 362) for an advanced supersonic jet trainer to replace the Folland Gnat T1 and Hawker Hunter T7, and a French requirement (the École de Combat et d'Appui Tactique, ECAT "tactical combat support trainer") for a cheap, subsonic dual role trainer and light attack aircraft to replace the Fouga Magister, Lockheed T-33 and Dassault Mystère IV.[1][2] In both countries several companies tendered designs: BAC, Hunting, Hawker Siddeley and Folland in Britain; Breguet, Potez, Sud-Aviation, Nord, and Dassault from France.[3] A Memorandum of Understanding was signed in May 1965 for the two countries to develop two aircraft, a trainer based on the ECAT, and the larger AFVG (Anglo-French Variable Geometry).[3]

Cross-channel negotiations led to the formation of SEPECAT (Société Européenne de Production de l'Avion d'École de Combat et d'Appui Tactique – the "European company for the production of a combat trainer and tactical support aircraft"[4]) in 1966 as a joint venture between Breguet[N 1] and the British Aircraft Corporation to produce the airframe. Though based in part on the Breguet Br.121, using the same basic configuration and an innovative French-designed landing gear, the Jaguar was built incorporating major elements of design from BAC, notably the wing and high lift devices.[5]

Production of components would be split between Breguet and BAC, and the aircraft themselves would be assembled on two production lines; one in the UK and one in France,[6] To avoid any duplication of work, each aircraft component had only one source.[7] The British light strike/tactical support versions were the most demanding design, requiring supersonic performance, superior avionics, a cutting edge nav/attack system of more accuracy and complexity than the French version, moving map display, laser range-finder and marked-target seeker (LRMTS). As a result, the initial Br.121 design needed a thinner wing, redesigned fuselage, a higher rear cockpit, and after-burning engines. While putting on smiling faces for the public, maintaining the illusion of a shared design, the British design departed from the French sub-sonic Breguet 121 to such a degree that it was effectively a new design.[8]

A separate partnership was formed between Rolls-Royce and Turbomeca to develop the Adour afterburning turbofan engine.[9][10] The Br.121 was proposed with Turbomeca's Tourmalet engine for ECAT but Breguet preferred the RR RB.172 and their joint venture would use elements of both. The new engine, which would be used for the AFVG as well, would be built in Derby and Tarnos.[11]

Previous collaborative efforts between Britain and France had been complicated – the AFVG programme ended in cancellation, and controversy surrounded the development of the supersonic airliner Concorde.[12] Whilst the technical collaboration between BAC and Breguet went well,[13] when Dassault took over Breguet in 1971 it encouraged acceptance of its own designs, such as the Super Étendard naval attack aircraft and the Mirage F1, for which it would receive more profit, over the Anglo-French Jaguar.[12][14]

The initial plan was for Britain to buy 150 Jaguar "B" trainers, with its strike requirements being met by the advanced BAC-Dassault AFVG aircraft, with France to buy 75 "E" trainers (école) and 75 "A" single-seat strike attack aircraft (appui). Dassault favoured its own Mirage G aircraft above the collaborative AFVG, and in June 1967, France cancelled the AFVG on cost grounds.[15] This left a gap in the RAF's planned strike capabilities for the 1970s;[15] at the same time as France's cancellation of the AFVG, Germany was expressing a serious interest in the Jaguar,[16] and thus the design became more oriented towards the low-level strike role.[17]

With the cancellation of both the BAC TSR-2 tactical strike aircraft and Hawker Siddeley P.1154 supersonic V/STOL fighter, the RAF were looking increasingly hard at their future light strike needs and realizing that they now needed more than just advanced trainers with some secondary counter insurgency capability. At this point, the RAF's proposed strike fleet was to be the American General Dynamics F-111s plus the AFVG for lighter strike purposes. There was concern that both F-111 and AFVG were high risk projects and with the French already planning on a strike role for the Jaguar, there was an opportunity to introduce a credible backup plan for the RAF's future strike needs – the Jaguar. As a result, by October 1970, the RAF's requirements had changed to 165 single-seat strike aircraft and 35 trainers.[13]

The Jaguar was to replace the McDonnell Douglas Phantom FGR2 in the close air support, tactical reconnaissance and tactical strike roles, freeing the Phantom to be used for air defence.[18] Both the French and British trainer requirements had developed significantly, and were eventually fulfilled instead by the Alpha Jet and Hawker Siddeley Hawk respectively.[19] The French, meanwhile, had chosen the Jaguar to replace the Aeronavale's Dassault Étendard IV, and increased their order to include an initial 40 of a carrier-capable maritime version of the Jaguar, the Jaguar M.[20] From these apparently disparate aims would come a single and entirely different aircraft: relatively high-tech, supersonic, and optimised for ground-attack in a high-threat environment.[21]

Prototypes

The first of eight prototypes flew on 8 September 1968, a two-seat design fitted with the first production model Adour engine.[22][23] This aircraft went supersonic on its third flight but was lost on landing on 26 March 1970 following an engine fire.[24] The second prototype flew in February 1969; a total of three prototypes flew at the Paris Air Show that year. The first French "A" prototype flew in March 1969. In October a British "S" conducted its first flight.[7]

.JPG.webp)

A Jaguar M prototype flew in November 1969. This had a strengthened airframe, an arrestor hook and different undercarriage: twin nosewheel and single mainwheels. After testing in France it went to RAE at Thurleigh for carrier landing trials from their land based catapult, after which, in July 1970, it underwent a series of shipboard trials from the French carrier Clemenceau. From these trials there were doubts about the throttle response in case of an aborted landing. The shipboard testing also revealed problems with the aircraft's handling when flying on one engine, although planned engine improvements were to have rectified these problems.[14] The "M" was considered a suitable replacement for the Etendard IV but the Aeronavale would only be able to afford 60 instead of 100 aircraft.[25]

In 1971, Dassault proposed the Super Étendard, claiming that it was a simpler and cheaper development of the existing Étendard IV, and in 1973, the French Navy ordered it instead of the Jaguar. However, rising costs meant that only 71 of the planned 100 Super Étendards were purchased.[14] The M was cancelled by the French government in 1973.[26]

Design

Overview

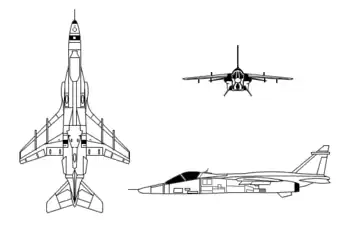

The Jaguar is an orthodox single-seat, swept-wing, twin-engine monoplane design, with tall tricycle-type retractable landing gear.[5] In its original configuration, it had a maximum take-off weight in the 15 tonne class;[27] with a combat radius on internal fuel of 850 km (530 mi), giving the Jaguar a greater operational range than competitor aircraft such as the Mikoyan MiG-27.[28] The aircraft had hardpoints fitted for an external weapons load of up to 10,000 lb (4,500 kg).[27] Typical weapons fitted included the Matra LR.F2 rocket pod, BAP 100-mm bombs, Martel AS.37 anti-radar missiles, AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles, and Rockeye cluster bombs.[29][30][31] The RAF's Jaguars gained several new weapons during the Gulf War, including CRV7 high-velocity rockets and American CBU-87 cluster bombs.[32] Finally, the Jaguar was equipped with either a pair of 30 mm autocannon - the French DEFA cannon, or British ADEN cannon.[33][34]

The Jaguar International had the unusual option of overwing pylons, used for short-range air-to-air missiles, such as the Matra R550 Magic or the Sidewinder. This option freed up the under-wing pylons for other weapons and stores. RAF Jaguars gained overwing pylons in the buildup to Operation Granby in 1990,[35] but French Jaguars were not modified.[36]

Engine

The SEPECAT Jaguar is powered by the Rolls-Royce Turbomeca Adour turbofan engine, which was developed in parallel with, and primarily for the Jaguar. A separate partnership was formed between Rolls-Royce and Turbomeca to develop the Adour, a two-shaft turbofan engine with afterburner.[9] Twin engines were selected for survivability. Ease of maintenance was major consideration, an engine change being possible within 30 minutes. For the Jaguars it needed a low bypass capable of high thrust for take off, supersonic flight and low level "dashes".[37]

When the first prototype Jaguar flew on 8 September 1968, it was also the first flight for the engine.[22] In its initial development the Adour engine had complications with the stability of the afterburner system,[38] and shipboard testing showed slow throttle response times, problematic in the situation of an aborted landing; engine improvements rectified these problems prior to the Jaguar coming into service.[14] In French service, the Jaguars were introduced using the original Mk.101 engine. RAF Jaguars entered service using the Mk.102 engine, mainly featuring better afterburner-throttle control over the Mk.101.[39] The RAF later had its Jaguars re-engined around 1981 with the improved Adour Mk.104, and again in 1999 with the Mk.106, each providing greater performance.[40][41]

The Adour was developed into both afterburning and non-afterburning models;[42] the Hawk, which had beaten the Jaguar to fulfill the Air Staff Target 362 trainer requirement, also used the non-afterburning Adour engine.[42] Other applications include the McDonnell Douglas T-45 Goshawk, the Mitsubishi T-2, and derived Mitsubishi F-1.[43]

Avionics

From the outset the Jaguar was equipped with a navigation and attack system. While A versions had a reliable double gyroscopic system and a Doppler radar derived from the Mirage IIIE, the GR1s had a totally new digital system with an inertial navigation system and a heads-up display, plus a Laser Ranging and Marked Targeting System (LRMTS) in the nose. These systems were a step above the current technology of the time, but reliability was quite low.

There were many more systems added with the time, like the Atlis II in the French aircraft, and, in 1994–95, some GR1s had laser-designator systems fitted. Missiles like AS-30 and the anti-ship Sea Eagle were added. Some IAF aircraft had the Agave radar system, purposely for maritime strike. India later developed the DARIN system in its Jaguar fleet, with a modern 1553 databus.

Although in operational theatres such as the Gulf War the Jaguar proved to be mechanically more reliable than the Panavia Tornado, the aircraft's avionics were a hindrance to conducting missions.[44] Owing to the Jaguar A's shortcomings in navigation and target acquisition, French Jaguars had to be escorted by Mirage F1CR reconnaissance aircraft to act as guides. The Jaguar provided a valuable component of the campaign, the RAF detachment of 12 Jaguars flew 612 combat sorties, with no aircraft lost.[45]

Significant changes were made both during and shortly after the war.[46] Owing to obsolete navigational systems being unable to provide the accuracy required, both French and British Jaguars were quickly modified with Global Positioning System (GPS) receivers, a recent technology at the time.[47] Prior to Operation Deliberate Force, the 1995 NATO bombing campaign in Bosnia and Herzegovina, a dozen Jaguars were upgraded with the capability to carry the TIALD laser designator pod and redesignated Jaguar GR1B or T2B respectively.[48] Shortly afterwards, the RAF upgraded its Jaguar fleet to a common standard, incorporating TIALD and the ability to use new reconnaissance pods. The interim GR3 (Jaguar 96) upgrade added a new HUD, a new hand controller and stick top, integrated GPS and TERPROM Terrain Referenced Navigation.[46][49] The further upgraded Jaguar GR3A introduced the new EO GP1 (JRP) digital reconnaissance pod, a helmet-mounted sight, improved cockpit displays, a datalink, and improved night vision goggles compatibility.[50]

A single Jaguar was converted into the Jaguar Active Control Technology (ACT) with fly-by-wire controls and aerodynamic alterations to the airframe; the aerodynamic instability improved manoeuvrability and the test data was used in the development of the Eurofighter.[51]

Operational history

France

The French Air Force took delivery of the first production Jaguar in 1973, one of an eventual 160 single-seat Jaguar As. For type conversion training, France also took 40 of the two-seat Jaguar E.[52] While the Jaguar was capable of carrying a single AN-52 nuclear bomb, the French government did not assign any Jaguars for use in the Force de frappe, France's strategic nuclear deterrent.[53] Nuclear armed Jaguars were instead assigned the "Pre-Strategic" role, to clear a path for the Strategic strike force.[54] The AN-52 nuclear bomb was retired from service in September 1991, when the formerly nuclear-armed squadrons of Escadre de Chasse 7 then concentrated on conventional attack.[55] French Jaguars also performed in the role of electronic counter measures (ECM) aircraft, bearing the Martel anti-radiation missile, capable of staying airborne to suppress enemy defences for long periods of time through mid air refuelling.[29]

In French service, the Jaguar was frequently deployed in defence of national interests in Africa during the 1970s, a policy sometimes referred to as "Jaguar diplomacy" (la diplomatie du Jaguar).[56] Jaguars made their combat debut against Polisario Front forces in Mauritania in December 1977, as part of Opération Lamantin.[9][57] In August 1978 a conventionally armed rapid reaction squadron was established, intended to deploy in support of French forces and interests anywhere in the world.[29]

France had been involved in the conflict in Chad for many years, and 2,000 men of the Force d'Intervention along with helicopters and Jaguars were deployed to defend central Chad in 1978; further forces arrived later as part of Opération Tacaud.[58] The Jaguars were engaged in May and June 1978, contributing significantly in halting an offensive by Goukouni Oueddei's FROLINAT forces, who were routed. One aircraft was shot down, but the pilot was recovered by helicopter.[59]

In support of the further military action in the region, known as Operation Manta, Jaguars were deployed to Bangui, Central African Republic, in 1983, before being rebased inside Chad at N'Djamena International Airport. On 25 January 1984, Jaguars attacked a rebel column that was withdrawing after raiding the town of Zigey. One aircraft was shot down and the pilot, Captain Michel Croci, was killed.[60] The "Manta" forces were withdrawn in 1984, as part of a de-escalation agreement, whereby both Libyan and French forces were to be withdrawn from Chad. The Libyans did not respect the agreement, and Jaguars returned to Chad in 1986, as part of Operation Epervier, this time with a more forceful role. On 16 February 1986, 11 Jaguars, escorted by Mirage F1 fighters and supported by Boeing C-135F tankers and Breguet Atlantic aircraft, launched a raid on the airfield at Wadi Doum, which the Libyans had constructed in Northern Chad, using BAP-100 anti-runway bombs.[61] In response to Libyan incursions, another strike was carried out on 7 January 1987, when a Jaguar destroyed a Libyan radar with a Martel missile.[59][62] The Jaguars stationed at Ndjamena were a target for Libyan sabotage owing to their effectiveness against enemy forces, but the attempts were unsuccessful.[63]

Persian Gulf War

France committed military assets to the Gulf War coalition; in October 1990, eight Jaguar A aircraft along with several Mirage F1CR reconnaissance aircraft were sent to the Middle East. The Mirages, which had more advanced avionics, acted as guides for the Jaguars.[64] Owing to obsolete navigational systems being unable to provide the accuracy required, both French and British Jaguars were quickly modified with GPS receivers, RAF Tornados also required adaption to a lesser extent.[47] The French Jaguar force in Saudi Arabia built up to a maximum of 28 aircraft, which carried out 615 combat sorties, with one Jaguar damaged by an Iraqi surface-to-air missile.[65] Typical targets were Iraqi armoured units, Scud missile sites, and naval vessels.[31]

On 17 January 1991, 12 French Jaguars bombed Ahmad al-Jaber Air Base, Kuwait; three were damaged in the attack but all returned to base.[31] On 26 January, RAF Jaguars and Tornados raided several Silkworm missile batteries in Kuwait to encourage the perception of an imminent amphibious invasion to liberate the country.[66] On the 30th, two RAF Jaguars destroyed a Polnochny-class landing ship with rockets and cannon.[67] The Iraqi Republican Guard, entrenched on the Kuwait-Saudi border, were subjected to a continuous intensive bombing campaign for weeks to demoralise them, allied Jaguars forming a portion of the delivering aircraft.[68] The Jaguars also performed valuable reconnaissance of the combat area for Coalition forces.[68] Both nations' Jaguars were withdrawn from the region in March 1991, at the end of Desert Storm.[68]

Subsequent Operations

In Operation Deliberate Force in 1995, six Jaguars based in Italy conducted 63 strike missions.[34] The last Jaguars in French service were retired in 2005, being replaced in the ground attack roles by the Dassault Rafale.[69]

United Kingdom

The RAF accepted delivery of the first of 165 single seat Jaguar GR1s (the service designation of the Jaguar S) with No 54 (F) squadron in 1974. These were supplemented by 35 two seat trainers, the Jaguar T2 (previously Jaguar B). The Jaguar S and B had a more comprehensive nav/attack system than the A and E models used by the French Air Force, consisting of a Ferranti/Marconi Navigation and Weapon Aiming Sub System (NAVWASS) and a Plessey 10 Way Weapon Control System. RAF Jaguars were used for rapid deployment and regional reinforcement,[70] and others flew in the tactical nuclear strike role, carrying the WE.177 bomb.[71]

Beginning in 1975 with 6 Squadron, followed by 54 Squadron based at RAF Coltishall, and a 'Shadow squadron', 226 OCU based at RAF Lossiemouth, Jaguar squadrons were declared operational to SACEUR with the WE.177.[72] 14 Squadron and 17 Squadron based at RAF Bruggen followed by 1977.[73][74] 20 Squadron and 31 Squadron also based at RAF Bruggen brought the RAF Jaguar force to its peak strength of six squadrons plus the OCU, each of twelve aircraft equipped with eight WE.177s. Two further squadrons, 2 Squadron and 41 Squadron based at RAF Laarbruch and RAF Coltishall respectively, were primarily tasked with tactical reconnaissance.[75] From 1975 the OCU's wartime role was as an operational squadron in the front line assigned to SACEUR with 12 Jaguar aircraft, eight WE.177 nuclear bombs, and a variety of conventional weapons.[76]

In April 1975, a single Jaguar was used to test the aircraft's rough airstrip capacity, by landing and taking off multiple times from the M55 motorway, the final test flight was conducted with a full weapons load; the ability was never used in service but was considered useful as improvised runways might be the only runways left available in a large scale European conflict.[77] In a high intensity European war, the role of the Jaguar was to support land forces on the continent in resisting a Soviet assault on Western Europe, striking targets beyond the forward edge of the battlefield should a conflict escalate. The apparent mismatch between aircraft numbers and nuclear bombs was a consequence of RAF staff planners concluding that there would be one third attrition of Jaguars in an early conventional phase, leaving the survivors numerically strong enough to deliver the allocated stockpile of 56 nuclear bombs.[76]

From December 1983, 75 Jaguar GR1s and 14 T2s were updated to the GR1A and T2A standards with FIN1064 navigation and attack systems replacing the original NAVWASS. At about the same time, most were also re-engined with Adour 104 engines and were fitted with the ability to carry Sidewinder air to air missiles or AN-ALQ-101(V)-10 electronic countermeasures pods under the wings.[40]

The RAF Jaguar force was altered in late 1984, when 17 Squadron, 20 Squadron and 31 Squadron exchanged their Jaguars for Tornado GR1s, although their assignment to SACEUR and their wartime role remained unchanged. The two other RAF Germany units, 14 Squadron and 2 Squadron, followed suit in 1985 and 1989 respectively, which left the operational Jaguar force concentrated in 6, 41 and 54 Squadrons at RAF Coltishall.[78][79]

1990 Gulf War

Following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, on 9 August 1990 the British government assigned an initial 12 Jaguar GR1A and 12 Tornado F3 aircraft to the Middle East in Operation Granby,[80] these aircraft operated from bases in Oman and Bahrain.[81] On 23 August 1990, a squadron of Tornado GR1 interdictors were dispatched to the region as well, but the Tornado GR1 was difficult to keep operational in the high temperatures.[44] Blackburn Buccaneers were dispatched in January 1991 to act as laser designators for the ground strike aircraft.[82] The RAF's Jaguars gained several new weapons during the Persian Gulf War, including CRV7 high-velocity rockets and American CBU-87 cluster bombs which were used because the RAF's existing BL755 bombs were designed for low-level release, and therefore unsuitable for higher-altitude operations common over the Persian Gulf.[32] The RAF's detachment of 12 Jaguars flew 612 combat sorties, with no aircraft being lost.[45] XZ364 "Sadman" flew 47 missions; the highest number of missions of any aircraft.[83]

Subsequent upgrades

In 1994, in order to meet an urgent need to increase the number of aircraft able to designate targets for laser-guided bombs, 10 GR1As and two T2As were upgraded with the capability to carry the TIALD laser designator pod and redesignated as Jaguar GR1B and T2B respectively.[48] TIALD equipped Jaguar GR1Bs were deployed to Italy in August to take part in Operation Deliberate Force against Bosnian Serb forces, being used to designate targets for RAF Harriers.[84] During the Bosnian operations, a Jaguar of 41 Squadron carried out the first RAF bombing raid in Europe since the end of the Second World War fifty years before.[85]

Following the success of the GR1B/T2B upgrade, the RAF launched a plan to upgrade its Jaguar fleet to a common standard, incorporating improvements introduced to some aircraft during the Gulf War, together with adding the ability to use TIALD and new reconnaissance pods. The upgrade came in two parts; the interim GR3 (Jaguar 96) upgrade added a new HUD, a new hand controller and stick top, integrated GPS and TERPROM Terrain Referenced Navigation. It was delivered in two standards, for recce and TIALD.[46][49] The further upgraded Jaguar GR3A (also known as Jaguar 97) introduced fleet-wide compatibility with TIALD and the new EO GP1 (JRP) digital reconnaissance pod, a helmet mounted sight, improved cockpit displays, a datalink, and improved night vision goggles compatibility.[50] All GR3As were subsequently re-engined with the new Adour 106 turbofan.[41] The RAF's Jaguar 97s were intended to be wired for the carriage of ASRAAMs on the overwing launchers, but clearance of this weapon was never completed because of funding cuts.[86][87]

The Jaguars did not see service in the 2003 Iraq War; they had been planned to operate from bases in Turkey, to the north of Iraq, but Turkey refused access to its airbases and the northern attack was cancelled.[88]

Demands by the UK Treasury to cut the defence budget led to Defence Secretary Geoff Hoon detailing plans on 21 July 2004 to withdraw the Jaguar by 2007. An expected out of service date of October 2007 was brought forward at just five days notice to 30 April 2007.[89] On 20 December 2007, a Jaguar operated by QinetiQ undertook the last British military Jaguar flight.[90]

Following their retirement from flying service, many Jaguars continue to serve as ground instructional airframes, most notably at RAF Cosford, used in the training of RAF fitters.

India

India had been approached as a possible customer for the Jaguar as early as 1968, but had declined, partly on the grounds that it was not yet clear if the French and British would themselves accept the aircraft into service.[91] India had already its Marut fighter-bomber, and tried to upgrade it with new engines, until the new project collapsed. A decade later IAF would become the largest single export customer, with a $1 billion order for the aircraft in 1978, the Jaguar being chosen ahead of the Dassault Mirage F1 and the Saab Viggen after a long and difficult evaluation process.[92][93] The order involved 40 Jaguars built in Europe at Warton, and 120 licence-built aircraft from Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) under the local name Shamsher ("Sword of Justice").[92][94]

As an interim measure, 18 RAF Jaguars were loaned to the IAF with the first two loaned aircraft operational with Western Air Command on 27 July 1979.[95] The second batch of aircraft for the IAF were 40 Jaguar Internationals built at Warton, the first aircraft being delivered in March 1981.[96] Batch Three was the assembly of another 45 aircraft by HAL of kits shipped from the United Kingdom, the first kit being shipped to India in May 1981.[96] In the following phases more aircraft would be built in India with less European content. A total of 80 aircraft were built by HAL.[96][97]

%252C_Malabar_07-2.jpg.webp)

Indian Jaguars were quite different from the RAF ones. The Adour Mk 811 engines were soon adopted in the HAL production line (the previous Jaguars made in UK had the earlier Mk 804), giving 8,400 lbf each. There were R-550 Magic 1 or 2 in rails over the wings. But more importantly, the NAWASS, even if very modern in conception, was replaced because it was found quite unreliable. The RAF was already upgrading the system with the modern Ferranti Type 1024 INS, but India was offered the 1024E export, less powerful version. So IAF instead pursued the development of new nav-attack system, called DARIN, that combined several technologies from France, UK and other sources. This system was more reliable and more precise than the older NAWASS and all the IAF Jaguars had it as standard. The Jaguar was found to be a long-range, fast, stable and effective strike aircraft in IAF service. Another important upgrade was the Maritime Strike version, fitted with a radar (the French Agave) and powerful British anti-ship missiles, produced in a very limited number (12). The only real issue with Jaguar is the lack of power at altitude, especially with heavy ordnance on board.

Indian Jaguars were used to carry out reconnaissance missions in support of the Indian Peace Keeping Force in Sri Lanka between 1987 and 1990.[98] They later played an active role in the 1999 Kargil War with Pakistan, dropping both unguided and laser-guided bombs,[98] the IAF defining its role as a "deep penetrating strike aircraft".[99] The Jaguar is also used in small numbers for the anti-ship role, equipped with the Sea Eagle missile.[94][100] The Jaguar remains an important element of the Indian military as, along with the Mirage 2000, the Jaguar has been described as one of the few aircraft capable of performing the nuclear strike role with reasonable chances of success.[101] It has been alleged that the Indian military decided against developing the Jaguar into an active nuclear platform because of its lack of ground clearance for deploying India's gravity-dropped nuclear bombs.[102]

As the aircraft aged, the avionics were viewed as lacking suitable components for the ground attack mission, such as terrain-following radar, GPS navigation or modern night-flight systems;[103] consequently, several upgrades were carried out in the mid-1990s, including the addition of the Litening targeting pod.[92] India placed an order for 17 additional upgraded Jaguar aircraft from Hindustan Aeronautics in 1999 and a further 20 in 2001–2002.[104] The IAF plans to upgrade up to 125 Jaguars starting in 2013 by upgrading the avionics (including multi mode radar, auto-pilot and other changes) as part of the DARIN III programme and is considering fitting more powerful engines, Honeywell F125IN, to improve performance, particularly at medium altitudes.[98] The latest upgrade program DARIN III (Display Attack Ranging Inertial Navigation) has also been approved. In addition to new avionics and equipment installed as part of DARIN II upgrade, DARIN III would feature modified avionics architecture, new cockpit with dual SMD, solid state flight data recorder and solid state video recording system, auto pilot system, integration of new multi-mode radar on Jaguar IS (currently only Jaguar IM are fitted with radars). Major structural modification would be carried out on the air frame to accommodate the radar. Initial Jaguars delivered to the IAF were powered by two Adour 804E; further deliveries were powered by Adour Mk811. All the current IAF Jaguars are powered by Adour Mk811. DARIN III upgrade will cause additional weight problems due to addition of new avionics and radar, resulting in it becoming underpowered. Later IAF took decisions not to upgrade the engines due to budget problems. As part of technology transfer agreement with Israeli Aerospace Industries (IAI) for 54 EL/M-2052 AESA radar to be manufactured by HAL Avionics Division, the first production version will be ready by March 2021 to be fitted on Jaguar IS as part of DARIN III UPG standard.[105]

In 2018, India cannibalised 31 airframes purchased from France, 2 airframes from UK and Oman each, few engines and several hundred types of critically needed spares for optimum squadron serviceability.[106]

Other operators

In 1969, while still in the prototype stage of development, formal approaches had been made to Switzerland, India, Japan, Australia, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany, promoting the aircraft for sale.[107] Japan began negotiations towards licensed production of the Jaguar,[108] but these plans failed in part because of the high royalty payments sought by SEPECAT.[108] A proposal for Turkey to construct Jaguars under licence also did not come to fruition.[109] Kuwait initially ordered 50 Jaguars and 16 Mirage 5s, but instead chose F1s.[110] Pakistan approached SEPECAT after the US refused to sell their aircraft of choice, the LTV A-7 Corsair II, due to an arms embargo; Pakistan eventually opted for Mirage 5s.[110]

Jaguars were successfully sold to a number of overseas countries, India being the largest operator. The Jaguar International was an export version which was sold to Ecuador, Nigeria and Oman. The Ecuadorian Air Force, the only Latin American export customer, purchased 10 single- and 2 two-seat variants, officially designated Jaguars ES and EB, respectively.[110] The first of twelve aircraft arrived in January 1977.[110] They were used mainly for ground attack roles and occasionally for air superiority duties during the Cenepa War with Peru in 1995, but the main part of the fleet was held in reserve in case of a wider conflict with the Peruvians.[111] Nigeria ordered 13 single-seat SN and 5 two-seat BN variants; SEPECAT delivered the first of these in May 1984.[110] A subsequent order for an 18-aircraft second batch was cancelled.[110] Some of those in service were withdrawn from operations on the grounds of economy, with the remaining aircraft put up for re-sale.[110] The Royal Air Force of Oman ordered 10 single-seat and 2 two-seat variants, designated Jaguars OS and OB, respectively; the first was delivered in March 1977.[110] A second identical 12-aircraft order was placed in the mid-1980s; these were joined by two secondhand Indian and RAF examples. The last of the Omani aircraft were retired on 6 August 2014.[112]

Variants

- Jaguar A

- Single-seat all-weather tactical strike, ground-attack fighter version for the French Air Force, two prototypes and 160 production aircraft built.[52]

- Jaguar B/Jaguar T2

- Two-seat training version for the Royal Air Force, one prototype and 38 production aircraft built.[40] Capable of secondary role of strike and ground attack.[113] Two flown by Empire Test Pilots School (ETPS) and one by Institute of Aviation Medicine. Equipped for inflight refuelling and with a single Aden cannon.[114]

- Jaguar T2A

- Jaguar T2 upgrade similar to GR1A, 14 conversions from T2.[40]

- Jaguar T2B

- Jaguar T4

- Jaguar T2A upgraded to Jaguar 96 standard.[116]

- Jaguar E

- Two-seat training version for the French Air Force, two prototypes and 40 production aircraft built.[52]

- Jaguar S / Jaguar GR1

- Single-seat all-weather tactical strike, ground-attack fighter version for the Royal Air Force, 165 built.[40] Equipped with NAVigation And Weapon Aiming Sub-System (NAVWASS) for attacking without use of radar. Ferranti "laser ranger and marked target seeker" added to nose during production[117] Engines replaced by Adour Mk 104 from 1978.[114]

- Jaguar M

- Single-seat naval strike prototype for the French Navy, one built.[52]

- Jaguar Active Control Technology

- One Jaguar converted into a research aircraft.

- Jaguar MAX

- Hindustan Aeronautics Limited-developed upgrade for the Indian Air Force S, M and B variant fleet. The upgrade suite was unveiled in February 2019 and includes new avionics, a reworked cockpit and integration of modern armaments.[118]

- Jaguar International

- Export versions based on either the Jaguar S or Jaguar B.

- Jaguar ES

- Export version of the Jaguar S for the Ecuadorian Air Force, 10 built.[119]

- Jaguar EB

- Export version of the Jaguar B for the Ecuadorian Air Force, two built.[119]

- Jaguar S(O)

- Export version of the Jaguar S for the Royal Air Force of Oman, 20 built.[120]

- Jaguar B(O)

- Export version of the Jaguar B for the Royal Air Force of Oman, four built.[120]

- Jaguar IS

- Single-seat all-weather tactical strike, ground-attack fighter for the Indian Air Force, 35 built by BAe[96] and 89 built by HAL (Shamser).[104]

- Jaguar IB

- Two-seat training version for the Indian Air Force, five built by BAe[96] and 27 built by HAL.[104]

- Jaguar IM

- Single-seat maritime strike aircraft for the Indian Air Force. Fitted with Agave radar and capable of carrying Sea Eagle anti-ship missile,[96] 12 built by HAL.[104] Upgraded with EL/M-2052.

- Jaguar SN

- Export version of the Jaguar S for the Nigerian Air Force, 13 built.[120]

- Jaguar BN

- Export version of the Jaguar B for the Nigerian Air Force, five built.[120]

Operators

Current

- Indian Air Force[121]

- No. 5 Squadron "Tuskers", IAF Ambala with Direct Supply (i.e. UK built) Jaguar IS and IB from August 1981.[122]

- No. 6 Squadron "Dragons", (Jaguar IM, IS, IB) from 1987.[123]

- No. 14 Squadron "Bulls", IAF Ambala. Operational from September 1980 with loaned RAF Jaguar GR1s and T2s, and re-equipped with Direct Supply Jaguar IS and IBs from March 1981.[122]

- No. 16 Squadron "Cobras". Equipped with Indian-built Jaguar IS and IB from October 1986.[122]

- No. 27 Squadron "Flaming Arrows". Equipped with Indian-built Jaguar IS and IB from June 1985.[122]

- No.224 Squadron "Warlords".[98]

Former operators

- Ecuadorian Air Force – ordered 10 single-seat EBs and 2 two-seat ESs in 1974, with the aircraft being delivered in 1977. It purchased 3 ex-RAF Jaguar GR.1s as attrition replacements in 1991.[119][124]

- Escuadron de Combate 2111 "Águilas" (Eagles)[119]

- French Air Force – all retired

- Escadron de Chasse 3/3 "Ardennes" at Nancy (1977–1987)[55]

- Escadron de Chasse 1/7 "Provence" at St Dizier. Re-equipped with Jaguars in May 1973 and declared operational September 1974.[55] It discarded the Jaguar in July 2005, the last French squadron to operate the Jaguar.[125]

- Escadron de Chasse 2/7 "Argonne" at St Dizier. French Jaguar OCU. Formed October 1974.[126] It was disbanded in June 2001.[125]

- Escadron de Chasse 3/7 "Languedoc" at St Dizier. Received first Jaguars in March 1974 and operational in July 1975.[127] Disbanded July 1997.[125]

- Escadron de Chasse 4/7 "Limousin". Formed April 1980 at St Dizier, but soon moved to Istres. Disbanded July 1989.[128]

- Escadron de Chasse 1/11 "Roussillon" at Toul. Operational March 1976.[129] Disbanded June 1994.[125]

- Escadron de Chasse 2/11 "Vosges" at Toul. Operational June 1977.[130] Disbanded July 1996.[125]

- Escadron de Chasse 3/11 "Corse" at Toul. Received Jaguars February 1975.[130] Disbanded July 1997.[125]

- Escadron de Chasse 4/11 "Jura" at Bordeaux-Mérignac. Formed August 1978, disbanded June 1992.[131]

- Nigerian Air Force ordered 13 Jaguar SNs & 5 Jaguar BNs in 1983, with delivery from 1984, being operated by a squadron at Makurdi.[120][124] Withdrawn from use in 1991 as an economy measure.[120] 14 examples were offered as a bulk lot purchase by Inter Avia Group on behalf of the Nigerian Air Force. (x11 single-seat variant and 3 trainers)[132]

- Royal Air Force of Oman purchased 10 Jaguar OSs and two Jaguar OBs in 1974, with an identical order following in 1980, supplementing these aircraft by an ex-RAF Jaguar T2 and GR1 in 1982 and 1986 respectively.[120][124] Oman's Jaguars were brought to full GR3A standards during the 1990s.[133] Oman's last four operational Jaguars were retired on 6 August 2014.[112]

- No. 8 Squadron RAFO at RAFO Thumrait.[120]

- No. 20 Squadron RAFO at RAFO Thumrait.[120]

- Royal Air Force – all retired

- No. 2 Squadron. JaguarGR.1/s replaced 2 Squadron's Phantoms at RAF Laarbruch, Germany in 1976, with a main role of tactical reconnaissance. It re-equipped with Tornado GR1As in 1988.[40]

- No. 6 Squadron JaguarGR.1A/GR.3/GR.3As formed at RAF Lossiemouth in October 1974, moving to RAF Coltishall in November 1974, serving in the attack role.[134] It moved to RAF Coningsby in April 2006, disbanding in May 2007.[135]

- No. 14 Squadron JaguarGR.1/GR.1As replaced its Phantoms with Jaguars in 1974, based at RAF Bruggen. Its Jaguars were replaced by Tornados in 1985.[134]

- No. 16 (Reserve) Squadron, JaguarGR.1/GR.1A/GR.3/T.4s the OCU was formed at RAF Lossiemouth by renumbering 226 OCU,[136] later moving Coltishall and finally disbanding in March 2005.[137]

- No. 17 Squadron at RAF Bruggen replaced its Phantoms in the strike role with JaguarGR.1s from 1975 to 1976, and re-equipped with Tornados in 1984–85.[134]

- No. 20 Squadron JaguarGR.1s formed at RAF Bruggen in February 1977 in the strike role, disbanding in June 1984.[136]

- No. 31 Squadron JaguarGR.1/GR.1As based at RAF Bruggen replaced its Phantoms in 1976 in the strike role. Its Jaguars were replaced by Tornados in 1984.[136]

- No. 41 Squadron JaguarGR.1/GR.1A/GR.3/GR.3As formed at RAF Coltishall in 1976 in the reconnaissance role.[136] It disbanded in April 2006.[138]

- No. 54 Squadron JaguarGR.1/GR.1A/GR.3/GR.3As formed at RAF Lossiemouth in March 1974 in the attack role, moving to RAF Coltishall in August 1974.[136] It disbanded in March 2005.[137]

- No. 226 OCU (Operational Conversion Unit) GR.1/GR.1A/T.2/T.2A/T.4s, formed at RAF Lossiemouth in October 1974 and was redesignated No. 16 (Reserve) Squadron in September 1991.[136]

- Jaguar Conversion Team at RAF Lossiemouth (initial OCU).[136]

- Empire Test Pilots' School.[139]

Surviving aircraft

France

- On display

- A91 Jaguar A, Gulf-War veteran with damage from an Iraqi SAM at Musée de l'air et de l'espace[140]

United Kingdom

- On display

- XX108 Jaguar GR1B is displayed in AirSpace at the Imperial War Museum Duxford[141]

- XX109 Jaguar GR1 at the City of Norwich Aviation Museum in Horsham St Faith, Norfolk.[142]

- XZ119 Jaguar GR1A at the National Museum of Flight, East Fortune Airfield, East Lothian. [143]

- XX734 Jaguar GR1 at BDAC Old Sarum Airfield Museum, Old Sarum, Wiltshire[144]

- XX741 Jaguar GR1A is in taxiable condition at the Bentwaters Airfield, Suffolk.[145]

Specifications (Jaguar A / S)

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1980–81,[27]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1 (A and S); 2 (B and E)

- Length: 16.83 m (55 ft 3 in) [lower-alpha 1]

- Wingspan: 8.69 m (28 ft 6 in)

- Height: 4.89 m (16 ft 1 in)

- Wing area: 24.18 m2 (260.3 sq ft)

- Aspect ratio: 3.12

- Empty weight: 7,000 kg (15,432 lb) typical, (dependent on variant and role)

- Gross weight: 10,954 kg (24,149 lb) full internal fuel and 120 rpg

- Max takeoff weight: 15,700 kg (34,613 lb) with external stores

- Fuel capacity: 4,200 L (1,100 US gal; 920 imp gal) internal, with provision for three 1,200 L (320 US gal; 260 imp gal) drop tanks on inboard and centreline pylons

- Powerplant: 2 × Rolls-Royce Turbomeca Adour Mk.102 afterburning turbofan engines, 22.75 kN (5,110 lbf) thrust each dry, 32.5 kN (7,300 lbf) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 1,350 km/h (840 mph, 730 kn) Mach 1.1 at sea level

- 1,699 km/h (1,056 mph; 917 kn) Mach 1.6 at 11,000 m (36,000 ft)

- Combat range: 815 km (506 mi, 440 nmi) hi-lo-hi (internal fuel)

- 575 km (357 mi; 310 nmi) lo-lo-lo (internal fuel)[lower-alpha 2]

- Ferry range: 1,902 km (1,182 mi, 1,027 nmi) with full internal and external tanks

- Service ceiling: 14,000 m (46,000 ft) [146]

- g limits: +8.6 (ultimate load +12)

- Time to altitude: 9,145 m (30,003 ft) in 1 minute 30 seconds[146]

- Wing loading: 649.3 kg/m2 (133.0 lb/sq ft) maximum

- Thrust/weight: Adour Mk.102: 0.422[lower-alpha 3]

- Take-off run: 580 m (1,900 ft) with typical tactical load

- Take-off run to 15 m (49 ft): 940 m (3,080 ft) with typical tactical load

- Landing run from 15 m (49 ft): 785 m (2,575 ft) with typical tactical load

- Landing run: 470 m (1,540 ft) with typical tactical load

- Landing speed: 213 km/h (132 mph; 115 kn)

Armament

- Guns: 2× 30 mm (1.181 in) calibre DEFA cannon with up to 150 rounds/gun

- Hardpoints: 7 (4× under-wing, 2× over-wing and 1× centreline) with a capacity of 10,000 lb (4,500 kg), with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets: 8× Matra rocket pods with 18× SNEB 68 mm rockets each

- Missiles:

- AS.37 Martel anti-radar missiles or

- 2× AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles on overwing pylons

- Rudram-1 anti-radiation missile (Indian Air Force)[147]

- Harpoon Anti-ship missile (Indian Air Force)[148]

- Sea Eagle Anti-ship missile (Indian Air Force)

- Precision-guided munition:

- DRDO Smart Anti-Airfield Weapon (Indian Air Force)

- Equipped only with French aircraft :2× AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles on outboard pylons

- 2× R.550 Magic air-to-air missiles on overwing pylons、AS-30L laser guided air-to-ground missile

- 1× AN-52 nuclear bomb

- Bombs: various unguided or laser-guided bombs or 2× WE177A nuclear bombs

- Other: ECM protection pods, Reconnaissance Pod, ATLIS laser/electro-optical targeting pod, external drop tanks for extended range/loitering time.

Avionics

Radar: EL/M-2052 AESA Radar, as a part of Indian Air Force (IAF) DARIN III upgrade program.[149]

See also

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

- IAR-93 Vultur

- LTV A-7 Corsair II

- Mikoyan MiG-27

- Mitsubishi F-1

- Nanchang Q-5

- Soko J-22 Orao

- Sukhoi Su-17

Related lists

References

Notes

- ↑ Breguet later merged to form Dassault-Breguet, subsequently Dassault Aviation

Citations

- 1 2 "Military Dassault aircraft: Jaguar." Archived 20 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Dassault Aviation. Retrieved: 15 November 2010.

- ↑ Bowman 2007, pp. 12–13.

- 1 2 Jackson 1992, p. 56.

- ↑ Wagner 2009, p. 122.

- 1 2 Jackson 1992, pp. 58, 71.

- ↑ Bowman 2007, pp. 14–17.

- 1 2 Flight 16 October 1969, p. 600.

- ↑ "Thunder & Lightnings - SEPECAT Jaguar - History".

- 1 2 3 Taylor 1980, p. 105.

- ↑ Taylor 1980, p. 708.

- ↑ Bowman 2007. p18-19

- 1 2 Wallace 1984, p. 27.

- 1 2 Jackson 1992, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 4 Jackson 1992, p. 77.

- 1 2 Segell 1998, p. 169.

- ↑ Segell 1998, p. 172.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, pp. 56, 58.

- ↑ Hobbs 2008, p.37.

- ↑ Wallace 1984, p. 28.

- ↑ Bowman 2007, p. 21.

- ↑ Wagner 2009, pp. 122–123.

- 1 2 Flight 12 September 1968, p. 391.

- ↑ Taylor 1971, p. 107.

- ↑ "The Year 1970". Ejection-history.org.uk. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ↑ Bowman 2007, p. 23-27.

- ↑ Bowman 2007, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 Taylor 1980, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Tellis 2001, p. 535.

- 1 2 3 Glenn 2005, p. 8.

- ↑ Glenn 2005, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 Glenn 2005, p. 40.

- 1 2 Jackson 1992, pp. 63–66.

- ↑ Wagner 2009, p. 123.

- 1 2 Owen 2000, p. 217.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, p. 64.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, p. 69.

- ↑ Bowman 2007, p. 19-20.

- ↑ Gunston, Bill. "The Phoenix of Derby." New Scientist, Vol. 52, No. 773, 9 December 1971, p. 76.

- ↑ Ford, T. "Rolls-Royce Adour." Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology, 51(3), 1979, pp. 2–5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jackson 1992, p. 94.

- 1 2 Thomas, Geoff. "More bite for Jaguars with upgraded Adour." Flight Daily News, 16 June 1999.

- 1 2 "Adour: Product Description." Rolls-Royce, Retrieved: 22 January 2011.

- ↑ Sekigawa 1980, p. 130.

- 1 2 Donald and Chant 2001, p. 34.

- 1 2 Jackson 1992, p. 93.

- 1 2 3 Barrie Flight International via flightglobal.com, 8–14 April 1998, pp. 30–32.

- 1 2 Russell and Hasik 2002, p. 151.

- 1 2 Lake Air International October 1997, pp. 226–228.

- 1 2 Lake Air International November 1997, pp. 274–276.

- 1 2 Lake Air International December 2000, pp. 359–360.

- ↑ SEPECAT Jaguar ACT Demonstrator. Archived 5 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine RAF Museum Cosford. Retrieved: 2 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Jackson 1992, p. 99.

- ↑ Croddy and Wirtz 2005, pp. 276, 361.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, pp. 80, 100.

- 1 2 3 Jackson 1992, p. 100.

- ↑ de Lespinois, Jérôme. "La diplomatie aérienne: The new gunboat diplomacy" (in French). Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Penser les Ailes françaises, Issue 24, 2010/2011. Retrieved: 19 January 2011.

- ↑ Forget, Michel. "Mauritanie 1977: Lamantin, une intervention extérieure à dominante air" (in French). Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Revue historique des armées, January 1992. Retrieved: 19 January 2011.

- ↑ Burr and Collins 2008, pp. 119, 124.

- 1 2 de Lespinois, Jérôme. "L'emploi de la force aérienne au Tchad (1967–1987)" (in French). Archived 5 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine Penser les Ailes françaises, Issue 6, June 2005, pp. 65–74. Retrieved: 19 January 2011.

- ↑ Shaked and Dishion 1984, p. 589.

- ↑ Burr and Collins 2008, p. 201.

- ↑ Cooper, Tom. "Libyan Wars, 1980–1989, Part 6." Air Combat Information Group, 13 November 2003. Retrieved: 19 January 2011.

- ↑ Burr and Collins 2008, p. 124.

- ↑ Donald and Chant 2001, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, p. 92.

- ↑ Glenn 2005, p. 41.

- ↑ Bowman 2007, pp. 174–175.

- 1 2 3 Glenn 2005, p. 44.

- ↑ "Rafale squadron inaugurated." Flight International via flightglobal.com, 4 July 2006.

- ↑ Eden 2004, p. 404.

- ↑ Cirincione et al. 2005, p. 199.

- ↑ "RAF nuclear front line Order-of-Battle 1975." nuclear-weapons.info. Retrieved: 15 November 2010.

- ↑ "RAF nuclear front line Order-of-Battle 1976." nuclear-weapons.info. Retrieved: 15 November 2010.

- ↑ "RAF nuclear front line Order-of-Battle 1977–78." nuclear-weapons.info. Retrieved: 15 November 2010.

- ↑ Wagner 2009, p. 124.

- 1 2 "WE.177 Carriage." nuclear-weapons.info. Retrieved: 15 November 2010.

- ↑ Glenn 2005, p. 19.

- ↑ "RAF nuclear front line Order-of-Battle 1984." nuclear-weapons.info. Retrieved: 15 November 2010.

- ↑ "RAF nuclear front line Order-of-Battle 1985." nuclear-weapons.info. Retrieved: 15 November 2010.

- ↑ Donald and Chant 2001, p. 32.

- ↑ Donald and Chant 2001, p. 33.

- ↑ Donald and Chant 2001, p. 35.

- ↑ Bowman 2007, p. 162.

- 1 2 3 Lake Air International October 1997, p. 228.

- ↑ "41 Squadron." Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Royal Air Force, 2011. Retrieved: 16 January 2011.

- ↑ Lake Air International December 2000, p. 360.

- ↑ Ripley, Tim. "Mixed news for contractors in UK defence spending plans." Flightglobal.com, 25 July 2000. Retrieved: 6 January 2011.

- ↑ "Cold War Squadrons: No. 41 Squadron." Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Royal Air Force Museum. Retrieved: 16 January 2011.

- ↑ "RAF News: RAF Jaguars leave service after 33 years." Archived 20 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Royal Air Force. Retrieved: 4 June 2011.

- ↑ Millard, Douglas. "QinetiQ says farewell with last ever UK Jaguar flight." Archived 29 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine Qinetiq. 20 December 2007. Retrieved: 15 November 2010.

- ↑ Cohen and Dasgupta 2010, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 Barua 2005, p. 274.

- ↑ Air International October 1988, pp. 177–181.

- 1 2 Eden 2004, pp. 400–401.

- ↑ Green et al. 1982, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jackson 1992, p. 108.

- ↑ "BAe Sepecat Jaguar IS/IB/IM "Shamsher"". www.bharat-rakshak.com.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilson and McBride 2009, p. 71.

- ↑ Abbas, Ahmed. "Indian Ambitions for Aerospace Supremacy: Options for Pakistan." Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad, Retrieved: 2 January 2011.

- ↑ Barua 2005, p. 378.

- ↑ Tellis 2001, p. 533.

- ↑ Tellis 2001, p. 542.

- ↑ Tellis 2001, p. 546.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilson and McBride 2009, p. 68.

- ↑ "HAL to Fly Production Version of AESA Radar in Jaguar Darin III Aircraft in March". Defense World. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ "First lot of Jaguar frames for ageing IAF fleet soon". Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Flight 16 October 1969, p. 604.

- 1 2 Lake 1994, p.139.

- ↑ Segell 1998, p. 168.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Eden 2004, p. 398.

- ↑ Cooper, Tom. "Peru vs. Ecuador; Alto-Cenepa War, 1995." Air Combat Information Group, 1 September 2003. Retrieved: 15 November 2010.

- 1 2 Oman retires last Jaguar strike aircraft – Flightglobal.com, 12 August 2014

- ↑ Bowman 2007, p. 237.

- 1 2 Bowman 2007, p. 113.

- 1 2 Bowman 2007, p. 117.

- 1 2 3 Lake Air International December 2000, p. 359.

- ↑ Bowman 2007, p. 112.

- ↑ Udoshi, Rahul (26 February 2019). "HAL showcases upgraded Jaguar MAX combat aircraft". Jane's 360. Bangalore. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Jackson 1992, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Jackson 1992, p. 111.

- ↑ Pandit, Rajat (23 July 2018). "IAF 'harvesting organs' of globally retired jets". The Times of India. The Times Group.

- 1 2 3 4 Lake Air International December 2001, pp. 345–346.

- ↑ Lake Air International December 2001, p. 346.

- 1 2 3 Taylor 1989, p. 143.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Francillon 2005, p. 25.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, p. 101.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, p. 102.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, p. 103.

- 1 2 Jackson 1992, p. 104.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, p. 105.

- ↑ "1983 SEPECAT JAGUAR Jets". trade-a-plane.com. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ↑ "Omani Air Force to Upgrade Jaguars." Flight Daily News, 16 November 1997.

- 1 2 3 Jackson 1992, p. 95.

- ↑ "RAF Leuchars Welcomes the Typhoon." Archived 8 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine Royal Air Force, 7 September 2010. Retrieved: 13 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jackson 1992, p. 96.

- 1 2 "RAF starts disbanding Jaguar squadrons ahead of Typhoon." Flight International via flightglobal.com, 15 March 2005. Retrieved: 16 January 2011.

- ↑ "Jaguars Depart." Flight International via flightglobal.com, 11 April 2006. Retrieved: 16 January 2011.

- ↑ Jackson 1992, p. 98.

- ↑ "SEPECAT Jaguar A n°91". Musée de l'Air et de l'Espace (in French). Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ "Thunder & Lightnings - SEPECAT Jaguar - Survivor XX108". www.thunder-and-lightnings.co.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ↑ "Aircraft List". City of Norwich Aviation Museum. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ↑ "SEPECAT Jaguar | National Museum of Flight". National Museums Scotland. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- ↑ https://www.boscombedownaviationcollection.co.uk/index_files/Page1514.htm. BDAC Old Sarum Museum website Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ↑ "Thunder & Lightnings - SEPECAT Jaguar - Survivor XX741". www.thunder-and-lightnings.co.uk. Retrieved 9 January 2024.

- 1 2 Donald and Lake 1996, p. 378.

- ↑ "Captive flight trials of anti-radiation missile soon". THE HINDU. 17 February 2016. Archived from the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ↑ "A first for IAF: Anti-ship Harpoon missile fired from fighter jet". Hindustan times. 29 May 2015.

- ↑ "HAL to Fly Production Version of AESA Radar in Jaguar Darin III Aircraft in March". Defense World. 3 February 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

Bibliography

- Barrie, Douglas (8–14 April 1998). "A Matter of Survival". Flight International. pp. 30–32. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012.

- Barua, Pradeep. The State at War in South Asia. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8032-1344-1.

- Bowman, Martin W. SEPECAT Jaguar. London: Pen and Sword Books, 2007. ISBN 1-84415-545-5.

- Burr, Millard and Robert Collins. Darfur: The Long Road to Disaster. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2008. ISBN 1-55876-470-4.

- Carbonel, Jean-Christophe. French Secret Projects 1: Post War Fighters. Manchester, UK: Crecy Publishing, 2016 ISBN 978-1-91080-900-6

- Cirincione, Joseph, Jon B. Wolfsthal and Miriam Rajkumar "Deadly Arsenals: Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Threats." Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Second edition 2005. ISBN 978-0-87003-216-5.

- Cohen, Stephen and Sunil Dasgupta. Arming Without Aiming: India's Military Modernization. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2010. ISBN 0-8157-0402-X.

- Croddy, Eric and James J. Wirtz. Weapons of Mass Destruction: An Encyclopedia on Worldwide Policy, Technology, and History – Volume 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2005. ISBN 1-85109-490-3.

- Cuny, Jean and Pierre Leyvastre. Les Avions Breguet (1940/1971). Paris: Editions Larivière, 1977. DOCAVIA vol. 6. OCLC 440863702

- "The Decade of the Shamsher: Part One". Air International, Vol. 35, No. 4, October 1988, pp. 175–183. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Donald, David and Christopher Chant. Air War in The Gulf 1991. London: Osprey Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1-84176-295-4.

- Donald, David and Jon Lake. World Encyclopedia of Military Aircraft Single Volume Edition. London: Aerospace Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-874023-95-6.

- Eden, Paul. The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London, UK: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- Francillon, René J. "Jaguar: The French Connection". Air International, Vol. 69 No. 3. pp. 20–25. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Glenn, Ashley. SEPECAT Jaguar in action. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 2005. ISBN 0-89747-491-0.

- Green, William, Gordon Swanborough and Pushpinder Singh Chopra, eds. The Indian Air Force and its Aircraft. London: Ducimus Books, 1982.

- Hobbs, David. "British F-4 Phantoms". Air International, Vol. 74, No. 4, May 2008, pp. 30–37. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Jackson, Paul. "SEPECAT Jaguar". World Air Power Journal. Volume 11, Winter 1992, pp. 52–111. London: Aerospace Publishing, 1992. ISBN 1-874023-96-4. ISSN 0959-7050.

- Lake, Jon. "Mitsubishi T-2: Supersonic Samurai". World Air Power Journal, Volume 18, Autumn/Fall 1994. London:Aerospace Publishing. ISBN 1-874023-45-X. ISSN 0959-7050. pp. 136–147.

- Lake, Jon. "Jaguar in India". Air International, Vol. 61, No. 6, December 2001. pp. 344–347. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Lake, Jon. "The Jaguar Sharpens its Claws". Air International, Vol. 59, No. 6, December 2000, pp. 356–360. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Lake, Jon. "SEPECAT Jaguar: The RAF's 'newest' Fast Jet: Part 1". Air International, Vol. 53, No. 4, October 1997, pp. 220–229. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Lake, Jon. "SEPECAT Jaguar: The RAF's 'newest' Fast Jet: Part 2". Air International, Vol. 53, No. 5, November 1997, pp. 273–280. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1971–72. London: Sampson Low Marston & Co, 1971. ISBN 0-354-00094-2.

- Owen, Robert C., ed. Deliberate Force: A Case Study in Effective Air Campaigning, Final Report of the Air University Balkans Air Campaign Study. Darby, PA: Diane Publishing, 2000. ISBN 1-58566-076-0.

- Russell Rip, Michael and James Hasik. The Precision Revolution: GPS and the Future of Aerial Warfare. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002. ISBN 1-55750-973-5.

- Segell, Glen. Weapons Procurement in Phase Considerations. London: Glen Segell Publishers, 1998. ISBN 1-901414-09-4.

- Sekigawa, Eiichiro. "Mitsubishi's Sabre Successor". Air International, Vol. 18, No, 3, March 1980, pp. 117–121, 130–131. Bromley, UK: Fine Scroll. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Shaked, Haim and Daniel Dishon, eds. Middle East Contemporary Survey, Vol. 8, 1983–84. Tel Aviv: The Moshe Dayan Center, 1986. ISBN 965-224-006-0.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1980–81. London: Jane's Publishing Company, 1980. ISBN 0-7106-0705-9.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1989–90. London: Jane's Publishing Company, 1989. ISBN 0-7106-0896-9.

- Tellis, Ashley J. India's Emerging Nuclear Posture: Between Recessed Deterrent and Ready Arsenal. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2001. ISBN 0-8330-2781-6.

- Wagner, Paul J. Air Force Tac Recce Aircraft: NATO and Non-aligned Western European Air Force Tactical Reconnaissance Aircraft of the Cold War. Pittsburgh, PA: Dorrance Publishing, 2009. ISBN 1-4349-9458-9.

- Wallace, William. Britain's Bilateral Links Within Western Europe. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984. ISBN 0-7102-0298-9.

- Wilson, Michael (16 October 1969). "Britain's Jaguar Emerges". Flight International. pp. 600–604. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012.

- Wilson, Séan and Liam McBride. "Indian Jaguars-Still on the Prowl". Air International, Vol. 77, No. 4, October 2009, pp. 66–71. Stamford, UK: Key Publishing. ISSN 0306-5634.

- "World News: Jaguar First Flight." Flight International via flightglobal.com, 12 September 1968, p. 391.

Further reading

- Lacaze, Henri (2016). Les avions Louis Breguet Paris [The Aircraft of Louis Breguet, Paris] (in French). Vol. 2: le règne du monoplan. Le Vigen, France. ISBN 978-2-914017-89-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)