A semimetal is a material with a very small overlap between the bottom of the conduction band and the top of the valence band. According to electronic band theory, solids can be classified as insulators, semiconductors, semimetals, or metals. In insulators and semiconductors the filled valence band is separated from an empty conduction band by a band gap. For insulators, the magnitude of the band gap is larger (e.g., > 4 eV) than that of a semiconductor (e.g., < 4 eV). Because of the slight overlap between the conduction and valence bands, semimetals have no band gap and a negligible density of states at the Fermi level. A metal, by contrast, has an appreciable density of states at the Fermi level because the conduction band is partially filled.[1]

Temperature dependency

The insulating/semiconducting states differ from the semimetallic/metallic states in the temperature dependency of their electrical conductivity. With a metal, the conductivity decreases with increases in temperature (due to increasing interaction of electrons with phonons (lattice vibrations)). With an insulator or semiconductor (which have two types of charge carriers – holes and electrons), both the carrier mobilities and carrier concentrations will contribute to the conductivity and these have different temperature dependencies. Ultimately, it is observed that the conductivity of insulators and semiconductors increase with initial increases in temperature above absolute zero (as more electrons are shifted to the conduction band), before decreasing with intermediate temperatures and then, once again, increasing with still higher temperatures. The semimetallic state is similar to the metallic state but in semimetals both holes and electrons contribute to electrical conduction. With some semimetals, like arsenic and antimony, there is a temperature-independent carrier density below room temperature (as in metals) while, in bismuth, this is true at very low temperatures but at higher temperatures the carrier density increases with temperature giving rise to a semimetal-semiconductor transition. A semimetal also differs from an insulator or semiconductor in that a semimetal's conductivity is always non-zero, whereas a semiconductor has zero conductivity at zero temperature and insulators have zero conductivity even at ambient temperatures (due to a wider band gap).

Classification

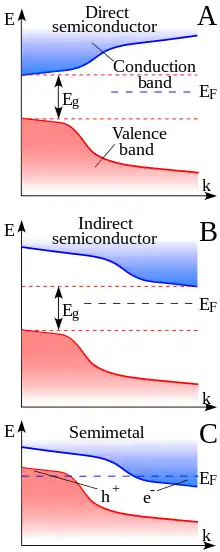

To classify semiconductors and semimetals, the energies of their filled and empty bands must be plotted against the crystal momentum of conduction electrons. According to the Bloch theorem the conduction of electrons depends on the periodicity of the crystal lattice in different directions.

In a semimetal, the bottom of the conduction band is typically situated in a different part of momentum space (at a different k-vector) than the top of the valence band. One could say that a semimetal is a semiconductor with a negative indirect bandgap, although they are seldom described in those terms.

Classification of a material either as a semiconductor or a semimetal can become tricky when it has extremely small or slightly negative band-gaps. The well-known compound Fe2VAl for example, was historically thought of as a semi-metal (with a negative gap ~ -0.1 eV) for over two decades before it was actually shown to be a small-gap (~ 0.03 eV) semiconductor[2] using self-consistent analysis of the transport properties, electrical resistivity and Seebeck coefficient. Commonly used experimental techniques to investigate band-gap can be sensitive to many things such as the size of the band-gap, electronic structure features (direct versus indirect gap) and also the number of free charge carriers (which can frequently depend on synthesis conditions). Band-gap obtained from transport property modeling is essentially independent of such factors. Theoretical techniques to calculate the electronic structure on the other hand can often underestimate band-gap.

Schematic

Schematically, the figure shows

- a semiconductor with a direct gap (e.g. copper indium selenide (CuInSe2))

- a semiconductor with an indirect gap (like silicon (Si))

- a semimetal (like tin (Sn) or graphite and the alkaline earth metals).

The figure is schematic, showing only the lowest-energy conduction band and the highest-energy valence band in one dimension of momentum space (or k-space). In typical solids, k-space is three-dimensional, and there are an infinite number of bands.

Unlike a regular metal, semimetals have charge carriers of both types (holes and electrons), so that one could also argue that they should be called 'double-metals' rather than semimetals. However, the charge carriers typically occur in much smaller numbers than in a real metal. In this respect they resemble degenerate semiconductors more closely. This explains why the electrical properties of semimetals are partway between those of metals and semiconductors.

Physical properties

As semimetals have fewer charge carriers than metals, they typically have lower electrical and thermal conductivities. They also have small effective masses for both holes and electrons because the overlap in energy is usually the result of the fact that both energy bands are broad. In addition they typically show high diamagnetic susceptibilities and high lattice dielectric constants.

Classic semimetals

The classic semimetallic elements are arsenic, antimony, bismuth, α-tin (gray tin) and graphite, an allotrope of carbon. The first two (As, Sb) are also considered metalloids but the terms semimetal and metalloid are not synonymous. Semimetals, in contrast to metalloids, can also be chemical compounds, such as mercury telluride (HgTe),[3] and tin, bismuth, and graphite are typically not considered metalloids.[4] Transient semimetal states have been reported at extreme conditions.[5] It has been recently shown that some conductive polymers can behave as semimetals.[6]

See also

References

- ↑ Burns, Gerald (1985). Solid State Physics. Academic Press, Inc. pp. 339–40. ISBN 978-0-12-146070-9.

- ↑ Anand, Shashwat; Gurunathan, Ramya; Soldi, Thomas; Borgsmiller, Leah; Orenstein, Rachel; Snyder, Jeff (2020). "Thermoelectric transport of semiconductor full-Heusler VFe2Al". Journal of Materials Chemistry C. 8 (30): 10174-10184. doi:10.1039/D0TC02659J. S2CID 225448662.

- ↑ Wang, Yang; N. Mansour; A. Salem; K.F. Brennan & P.P. Ruden (1992). "Theoretical study of a potential low-noise semimetal-based avalanche photodetector". IEEE Journal of Quantum Electronics. 28 (2): 507–513. Bibcode:1992IJQE...28..507W. doi:10.1109/3.123280.

- ↑ Wallace, P.R. (1947). "The Band Theory of Graphite". Physical Review. 71 (9): 622–634. Bibcode:1947PhRv...71..622W. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.71.622. S2CID 53633968.

- ↑ Reed, Evan J.; Manaa, M. Riad; Fried, Laurence E.; Glaesemann, Kurt R.; Joannopoulos, J. D. (2007). "A transient semimetallic layer in detonating nitromethane". Nature Physics. 4 (1): 72–76. Bibcode:2008NatPh...4...72R. doi:10.1038/nphys806.

- ↑ Bubnova, Olga; Zia, Ullah Khan; Wang, Hui (2014). "Semi-Metallic Polymers". Nature Materials. 13 (2): 190–4. Bibcode:2014NatMa..13..190B. doi:10.1038/nmat3824. PMID 24317188. S2CID 205409397.