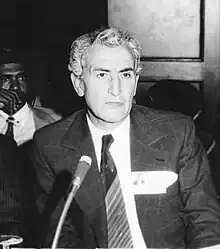

Seghir Mostefai (1926 – 21 January 2016) was an Algerian lawyer, economist and high civil servant. He graduated with a master's degree in law and economics from Sorbonne University, Paris. Long time anti-colonial activist with responsibilities in the political independentist organization in Algeria and later in exile in Tunis, he participated to the negotiation of the Évian Accords leading to the independence of Algeria. He founded the Central Bank of Algeria, created the national currency and served as Governor of the Central Bank, representing Algeria at the board of the IMF for 20 years.

Mostefai played a key role in the negotiations for the liberation of the American hostages in Tehran in 1981. He died on 21 January 2016, at the age of 89.[1]

The Evian Accords

Missioned by the Gouvernement Provisoire de la République algérienne (Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic) known as GPRA, based in Tunis, Seghir Mostefai was a member of the Algerian delegation that negotiated the “Évian Accords” for the independence of Algeria signed on March 18, 1962.

Confusion is often made with his uncle Dr Chawki Mostefai, one of the leaders of the anti-colonialist movement, member of the GPRA, known for being the designer of the Algerian flag which was displayed during the demonstrations of May 8, 1945. After secretly meeting with him in Morocco in 1962, Nelson Mandela referred to him as his first political mentor.[2][3][4]

Central Bank of Algeria

Creation of BCA

During the years preceding the independence of Algeria, Seghir Mostefai was based in Tunis and was hired by the Tunisian government as an expert for the Ministry of Finance and an adviser to Governor of the Central Bank of Tunisia.

Immediately after the independence was proclaimed he was in charge of representing the Algerian government at the board of Banque de l'Algérie, the French colonial monetary institution, to create within a few months the new independent Algerian central bank “Banque Centrale d’Algérie” (BCA) and to represent Algeria at the boards of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

Algerian Dinar and gold reserves

In 1964, he created the national currency, the Algerian Dinar, and later set up the country's sovereign printing of banknotes, making Algeria the first country in the Arab world and in Africa to be able to print its money independently. The BCA assisted several African countries to create their central banks, their national currencies and to have their money printed in Algeria.

In 1971, after the United States had decided to put an end to the international convertibility of the US Dollar to gold, he obtained from the Federal Reserve to make an exception for Algeria which enabled him to create the first gold reserves of the country.[5]

International organizations

Very active to promote the interests of Third World nations in the International Monetary Fund he was one of the three founders[6][7] of the Group of 24 (G-24) in 1971. He represented Algeria at the Arab Monetary Fund and collaborated as an expert with international organizations like UNCTAD and UNDP.

Readmission of China (PRC) in the International Monetary Fund

In 1980, the International Monetary Fund decided to recognize the People's Republic of China (PRC) rather than the Republic of China (ROC).[8] Based on his experience and reputation after a very long period of time representing Algeria and the interests of emerging countries in general with the G-24 in the international financial institutions, he was asked by the government of the People's Republic of China to introduce the country's application for membership at the International Monetary Fund, to represent China during the membership process and thus to organize its come-back into the international monetary and financial community.[9]

Negotiations for the release of the American hostages in Iran

On November 2, 1980, the Iranian parliament voted[10] the decision to free the American citizens detained in Iran if the United States agree to release the Iranian assets frozen in U.S. banks, to return the wealth[11] amassed by the Shah[12] and to pledge not to interfere in the Iranian internal affairs in the future.[13][14]

Several personalities had proposed to act as go-between such as former U.S. attorney general Ramsey Clark[15] sent by president Jimmy Carter, former Prime Minister of Sweden Olof Palme, UN General Secretary Kurt Waldheim with no result, because of the complexity of the financial litigation between the two countries’ public and private entities.

The Algerian government composed a team comprising their ambassadors to each country. The two ambassadors started to shuttle between Tehran and Algiers where the American delegation had arrived.[16] As diplomats with no experienced of complex negotiations and international financial arbitration their role was limited to forwarding messages and were referred in the American media as "the mailmen".[17][18]

The ambassadors arranged to meet with the hostages in Tehran and to check on their health. They collected letters from the hostages and organised a gathering at the Algerian embassy in Washington DC to deliver the letters to the hostages' families.[19] But their contribution to the resolution of the crisis could not go further.[20][21]

The political aspect of the negotiation was rapidly solved, the United States confirming that "it is and from now on will be the policy of the United States not to intervene, directly or indirectly, politically or militarily, in Iran's internal affairs".[22][23]

After the negotiation stalled[24][18][25] the Algerian minister of foreign affairs was unable to progress and called upon the help of the governor of the central bank[26] He was very well known for a long time by the representatives of the Federal Reserve Bank as a member of the international financial community and by the governor of the central bank of Iran. He was also able to build good relations with the Iranian negotiation team known as the "Nabavi Committee".[27] The difficulty of the negotiation was to determine which claims could be considered as legitimate by the two sides knowing that the Iranian government estimated frozen assets at $24 billion. He proposed a solution which consisted in the release of a significant portion of the Iranian frozen assets and the repayment to the United States of the Iranian sovereign debt through escrow accounts and at a later stage the creation of an arbitration tribunal to resolve pending disputes such as losses caused to American corporations and individuals by the revolution and Iranian claims in the United States was accepted by the two parties.[28] He offered the guarantee of the Algerian Central Bank to receive unfrozen funds on an escrow account. The solution he designed was formalized by the "Algiers Accord" signed on January 19, 1980. When the Algerian Central Bank received Iranian assets[29] transferred by the United States on its account at the Bank of England, the signal was given for the release of the American hostages on January 20, 1981.

References

- ↑ "Seghir Mostefaï, fondateur de la Banque d'Algérie et père du dinar". El Watan. 23 January 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- ↑ "Nelson Mandela meets Dr Mostefai, head of the Algerian diplomatic mission in Morocco and presents him with a memo – Nelson Mandela Foundation". www.nelsonmandela.org. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ↑ Youcef, Abdeldjalil Larbi (2014). ""The Algerian Army Made Me a Man"". Transition (116): 67–79. doi:10.2979/transition.116.67. ISSN 0041-1191. JSTOR 10.2979/transition.116.67. S2CID 153614543.

- ↑ "Reuters Archive Licensing". Reuters Archive Licensing. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ↑ "Notre premier stock en or avait été constitué grâce à la clairvoyance et la perspicacité de Seghir Mostefaï, le premier gouverneur de la Banque centrale, qui a géré l’institution pendant près de vingt ans avec compétence, efficacité et discrétion, sans jamais chercher à se prévaloir de ce qu’il accomplissait. Il avait acheté l’or à 35 dollars US l’once avant que les Etats-Unis ne décident, en 1971, de suspendre la convertibilité du dollar en or et de mettre fin ainsi au cours fixe de ce dernier." Contribution : Les réserves de change et leur gestion Bader Eddine Nouioua (Ancien gouverneur de la Banque centrale d’Algérie) 28 décembre 2011 https://www.elwatan.com/archives/economie-archives/contribution-les-reserves-de-change-et-leur-gestion-28-12-2011

- ↑ Mayobre, Eduardo (1999). G-24: The Developing Countries in the International Financial System. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1555878466.

- ↑ International Monetary Fund, The International Monetary 1972-1978 : Cooperation on Trial Volume III : Documents, International Monetary Fund. International Monetary Fund. 1996. ISBN 978-1-4639-9333-7.

- ↑ Boughton, James (2001). Silent Revolution, The International Monetary Fund 1979–1989. International Monetary Fund. p. 967.

- ↑ Benamraoui, A.; Boukrami, E. (1 February 2014). A History of the Algerian Banking Industry 1830-2010. New York, USA: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-0047-4.

- ↑ "Iran willing to release hostages" (PDF). The Daily Guardian.

- ↑ Branigin, William (17 January 1979). "Pahlavi Fortune: A Staggering Sum". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ "Ramsey Clark Advised Iran on Damages From Shah (Published 1979)". The New York Times. 21 November 1979. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ "SIGNIFICANT DATES IN THE HOSTAGE CRISIS (Published 1981)". The New York Times. Associated Press. 21 January 1981. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ "Khomeini Declares Terms For Freeing U.S. Hostages". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Ramsey Clark Ending Attempt to Reach Iran (Published 1979)". The New York Times. 15 November 1979. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ John M. Goshko (11 November 1980). "Christopher Flies To Algeria Bearing U.S. Reply to Iran". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Algeria started out as ''a simple mailman,'' delivering messages between the United States and Iran, but in the end it played a decisive mediator's role in the negotiations for the release of the 52 American hostages and the return to Iran of assets frozen in the United States." Marvine Howe, New York Times Jan. 26, 1981

- 1 2 Marvine Howe. "WARY ALGERIA EDGED INTO PIVOTAL ROLE". The New York Times.

- ↑ Barringer, Felicity (30 December 1980). "Photos, Letters Bring Bittersweet Comfort to Hostages' Families". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ↑ "The participation of financial leaders in the second American delegation did not surprise Algiers, in view of the Iranian demands pertaining to the Shah's assets and Iranian funds in the United States, but there was doubt as to what role Algeria could play in handling these particular aspects of the negotiations." CIA-RDP82-00850R000300080014-5.pdf

- ↑ "Near East / North Africa Report CIA-RDP82-00850R000300080014-5" (PDF).

- ↑ "Algiers Accords".

- ↑ "Iran hostage crisis negotiations".

- ↑ Algerian sources close to the negotiations said Algeria had faithfully observed its role as an intermediary until about a month ago, when ''a deadlock'' was reached between American and Iranian negotiators. Marvine Howe, New York Times Jan. 26, 1981

- ↑ p. 158 : "So there were several rounds of discussion.Christopher came a couple of times to Algiers where it was easy to communicate quickly with the Iranians through the Algerian Foreign Ministry, but these efforts had been unsuccessful.In early December, as I recall, we got instructions for our Chargé then, Chris Ross, now ambassador to Syria, to go to the Foreign Ministry and ask them if the Carter Administration should make one last effort to arrive at an agreement, or whether they should just give up and leave it to the Reagan administration --Reagan had already been elected by then." RICHARD SACKETT THOMPSON Political Counselor Algiers (1980-1982) https://adst.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Algeria.pdf

- ↑ "MOSTEFAI COMES TO THE RESCUE In Tehran Seghir Mostefai did wonders. His history as a financial expert in the GPRA delegation in Evian and his long experience as the head of the Central Bank of Algeria made him immediately welcomed by the Iranians who were listening to all his intervention with the admiring respect due to high competence. First he knew how to tactfully reduce the mistrust of his interlocutors and to explain in simple terms the complex financial mechanism by which the assets would be transferred as soon as they would be unfrozen." M. S. Dembri, General Secretary of the Algerian Ministry of foreign Affairs in "La Tribune" dated May 21st 1996

- ↑ Relations, United States Congress Senate Committee on Foreign (1981). The Iran Agreements: Hearings Before the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, Ninety-seventh Congress, First Session, February 17, 18 and March 4, 1981. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ "Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal".

- ↑ Washington Post (20 December 1980). "Iran Dashes Hopes for Hostages' Christmas Release". The Washington Post.