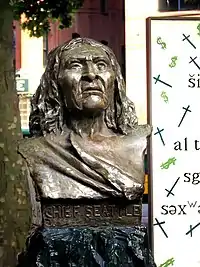

Chief Seattle | |

|---|---|

siʔaɬ | |

Only known photograph of Seattle, 1864 | |

| Suquamish & Duwamish leader | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1780[1][2] Blake Island |

| Died | June 7, 1866 (aged 85–86) Port Madison |

| Resting place | Port Madison, Washington, U.S. |

| Spouses |

|

| Relations | Doc Maynard |

| Children | 8, including Princess Angeline |

| Parents |

|

| Known for | Namesake of Seattle, Washington, and his speech on the land treaty |

| Nickname | Parents were known to call him "Se-Se" |

Chief Seattle (c. 1786 – June 7, 1866) was a Suquamish and Duwamish chief.[3] A leading figure among his people, he pursued a path of accommodation to white settlers, forming a personal relationship with "Doc" Maynard. The city of Seattle, in the U.S. state of Washington, was named after him. A widely publicized speech arguing in favour of ecological responsibility and respect of Native Americans' land rights had been attributed to him.

The name Seattle is an Anglicization of the modern Duwamish conventional spelling Si'ahl, equivalent to the modern Lushootseed spelling siʔaɫ Lushootseed pronunciation: [ˈsiʔaːɬ] and also rendered as Sealth, Seathl or See-ahth. According to elder taqʷšəbluʔ, his name was traditionally pronounced siʔaƛ̕.[4]

Biography

Seattle's mother Sholeetsa was dxʷdəwʔabš (Duwamish) and his father Shweabe was chief of the suq̓ʷabš (Suquamish).[3][5] Seattle was born some time between 1780 and 1786 on Blake Island, Washington. One source cites his mother's name as Wood-sho-lit-sa.[6] The Duwamish tradition is that Seattle was born at his mother's village of stukʷ on the Black River, in what is now the city of Kent, Washington, and that Seattle grew up speaking both the Duwamish and Suquamish dialects of Lushootseed. Because Native descent among the Salish peoples was not solely patrilineal, Seattle inherited his position as chief of the Duwamish Tribe from his maternal uncle.[3]

Seattle earned his reputation at a young age as a leader and a warrior, ambushing and defeating groups of tribal enemy raiders coming up the Green River from the Cascade foothills.

Like many of his contemporaries, he owned slaves captured during his raids.[7][8] He was tall and broad, standing nearly six feet (1.8 m) tall; Hudson's Bay Company traders gave him the nickname Le Gros (The Big Guy). He was also known as an orator; and when he addressed an audience, his voice is said to have carried from his camp to the Stevens Hotel at First and Marion, a distance of 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km).[6]

Chief Seattle took wives from the village of Tola'ltu just southeast of Duwamish Head on Elliott Bay (now part of West Seattle). His first wife La-Dalia died after bearing a daughter. He had three sons and four daughters with his second wife, Olahl.[6] The most famous of his children was his first, Kikisoblu or Princess Angeline. His grandniece, Rebecca Lena Graham, is also notable for her successful inheritance claim following the Graham v. Matthias, 63 F. 523 (1894) case. Seattle was converted to Christianity by French missionaries, and was baptized in the Catholic Church, with the baptismal name Noah, probably in 1848 near Olympia, Washington.[9]

For all his skill, Seattle was gradually losing ground to the more powerful Patkanim of the Snohomish when white settlers started showing up in force around 1850. (In later years, Seattle claimed to have seen the ships of the Vancouver Expedition as they explored Puget Sound in 1792.) When his people were driven from their traditional clamming grounds, Seattle met Doc Maynard in Olympia; they formed a friendly relationship useful to both. Persuading the settlers at the white settlement of Duwamps to rename their town Seattle, Maynard established their support for Chief Seattle's people and negotiated relatively peaceful relations with the tribes.

Seattle kept his people out of the Battle of Seattle in 1856. Afterwards, he was unwilling to lead his tribe to the reservation established, since mixing Duwamish and Snohomish was likely to lead to bloodshed. Maynard persuaded the government of the necessity of allowing Seattle to remove to his father's longhouse on Agate Passage, 'Old Man House' or Tsu-suc-cub. Seattle frequented the town named after him, and had his photograph taken by E. M. Sammis in 1865.[6] He died June 7, 1866, on the Suquamish reservation at Port Madison, Washington.[10]

The speech or "letter"

The speech or "letter" attributed to Chief Seattle has been widely cited as a "powerful, bittersweet plea for respect of Native American rights and environmental values".[11] But this document, which has achieved widespread fame thanks to its promotion in the environmental movement, is of doubtful authenticity. Although Chief Seattle evidently gave a speech expressing such feelings in 1854 to Isaac Stevens, the Governor of Washington Territories at the time, it was not documented until nearly a quarter century later by Dr. Henry Smith. Smith who stated in the October 29, 1887, edition of the Seattle Sunday Star that his documentation of the speech was based on notes he took at the time. The speech was delivered in Seattle's native Lushotseed language, translated into Chinook jargon, and then into English.[12]

.jpg.webp)

Legacy

- Seattle's grave site is at the Suquamish Tribal Cemetery.[13]

- In 1890, a group of Seattle pioneers led by Arthur Armstrong Denny set up a monument over his grave, with the inscription "SEATTLE Chief of the Suqampsh and Allied Tribes, Died June 7, 1866. The Firm Friend of the Whites, and for Him the City of Seattle was Named by Its Founders" On the reverse is the inscription "Baptismal name, Noah Sealth, Age probably 80 years."[6] The site was restored and a native sculpture added in 1976 and again in 2011.

- Soundgarden, a Seattle rock band, covered the Black Sabbath song, "Into the Void" replacing the lyrics with the words from what was incorrectly alleged to be Chief Seattle's speech.

- The Suquamish Tribe honors Chief Seattle every year in the third week of August at "Chief Seattle Days".

- The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America commemorates the life of Seattle on June 7 in its Calendar of Saints. The liturgical color for the day is white.[14]

- The city of Seattle, and numerous related features, are named after Seattle.

- A B-17E Flying Fortress, SN# 41-2656 named Chief Seattle, a so-called "presentation aircraft", was funded by bonds purchased by the citizens of Seattle. Flying with the 435th Bombardment Squadron out of Port Moresby, it was lost with its 10-man crew on August 14, 1942.[15][16]

- The Chief Sealth Trail in southern Seattle is named after Chief Seattle.[17]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Chief Si'ahl". Duwamish Tribe.

- ↑ "Chief Seattle | The Suquamish Tribe". Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Chief Si'ahl and His Family". Culture and History. Duwamish Tribe. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- ↑ "Chief Seattle (Seattle, Chief Noah [born Si?al 178?-1866])". www.historylink.org. Retrieved January 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Chief Si'ahl".

- 1 2 3 4 5

- Emily Inez Denny (1899). Blazing the Way (reprinted 1984 ed.). Seattle Historical Society.

- ↑ Buerge, David M. "Chief Seattle and Chief Joseph: From Indians to Icons". University of Washington.

Despite an attribution of slavery in his lineage, Seattle's noble status was affirmed by his reception of Thunderbird power from an important supernatural wealth-giver during a vision quest held sometime during his youth. He married well, taking wives from the important village of Tola'ltu on the western shore of Elliott Bay. His first wife died after bearing a daughter, but a second bore him sons and daughters, and he owned slaves, always a sign of wealth and status

- ↑ David M. Buerge (2017) Chief Seattle and the Town That Took His Name: The Change of Worlds for the Native People and Settlers on Puget Sound page 55, 60-61 ISBN 978-1632171351

- ↑ Buerge, David M. "Chief Seattle and Chief Joseph: From Indians to Icons". University of Washington. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ↑ Gifford, Eli (2015). The Many Speeches of Chief Seattle (Seathl): The Manipulation of the Record on Behalf of Religious Political and Environmental Causes. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-1-5187-4949-0.

- ↑ "Chief Seattle's Speech". HistoryLink. 2001. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ↑ Jeffers, Susan. Brother Eagle, Sister Sky. New York, NY: Dial Books (Division of Penguin); 1991 (OCLC 733769707)(ISBN 9780803709638)

- ↑ "Suquamish Culture". Suquamish Tribe. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ↑ "The Church Year" (PDF). Renewing Worship. January 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 8, 2006. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ↑ Salecker, Gene E.; Salecker, E. (October 9, 2007). "Chief Seattle" and Crew. ISBN 9780306817151. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

- ↑

- Gene Eric Salecker (2001). Fortress Against the Sun bob. Da Capo Press. 978-1580970495.

- ↑ "Chief Sealth Trail". Retrieved February 12, 2012.

Additional references

- Lakw'alas (Thomas R. Speer), The Life of Seattle, 'Chief Seattle', Duwamish Tribal Services board of directors, for the Duwamish Tribe, July 22, 2004.

- Murray Morgan, Skid Road, 1951, 1960, and other reprints, ISBN 0-295-95846-4.

- William C. ("Bill") Speidel, Doc Maynard, The Man Who Invented Seattle, Nettle Creek Publishing Company, Seattle, 1978.

- Chief Seattle bio, Chief Seattle Arts, accessed online 2009-02-23.

- The Suquamish Museum (1985). The Eyes of Chief Seattle. Suquamish, WA: Suquamish Museum.

- Jefferson, Warren (2001). The World of Chief Seattle, How Can One Sell the Air?. Summertown, TN: Native Voices. p. 127. ISBN 1-57067-095-1.

- Fox, Emily (December 11, 2017). "A rare move by Chief Seattle changed the future of the city". KUOW Puget Sound Public Radio. KUOW-FM.

External links

- Suquamish Museum & Cultural Center

- Chief Seattle and Chief Joseph: From Indians to Icons - University of Washington Library

- Chief Seattle grave (The Traveling Twins videoclip)

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.