.svg.png.webp) | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | Early Middle Ages |

| Type | Judiciary |

| Jurisdiction | Scotland |

| Headquarters | Judicial Office for Scotland, Parliament House, Edinburgh, EH1 1RQ |

| Annual budget | £51.7 million (2013-14)[1] |

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent department | Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service |

| Website | www |

| Map | |

Scotland in the UK and Europe | |

| Part of a series on |

| Scots law |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

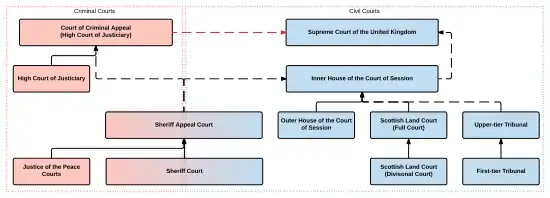

The judiciary of Scotland (Scottish Gaelic: Breitheamh na h-Alba) are the judicial office holders who sit in the courts of Scotland and make decisions in both civil and criminal cases. Judges make sure that cases and verdicts are within the parameters set by Scots law, and they must hand down appropriate judgments and sentences. Judicial independence is guaranteed in law, with a legal duty on Scottish Ministers, the Lord Advocate and the Members of the Scottish Parliament to uphold judicial independence, and barring them from influencing the judges through any form of special access.

The Lord President of the Court of Session is the head of Scotland's judiciary and the presiding judge of the College of Justice (which consists of the Court of Session and High Court of Justiciary.) As of May 2016, the Lord President was Lord Carloway, who was appointed in December 2015 having previously served as Lord Justice Clerk. The Lord President is supported by the Judicial Office for Scotland which was established on 1 April 2010 as a result of the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008, and the Lord President chairs the corporate board of the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service.

The second most senior judge is the Lord Justice Clerk, and the other judges of the College of Justice are called Senators. When sitting in the Court of Session, Senators are known as Lords of Council and Session, and when sitting in the High Court of Justiciary they are known as Lords Commissioners of Justiciary. There are also some temporary judges who carry out the same work on a part-time basis.

Scotland's sheriffs deal with most civil and criminal cases. There are 6 sheriffdoms, each administered by a sheriff principal. Sheriffs principal and sheriffs are legally qualified, and previously serve as either advocates or solicitors, though many are also King's Counsel. Summary sheriffs deal exclusively with cases under summary procedure, and some advocates and solicitors serve as part-time sheriffs. In 2014, Justice of the Peace courts replaced the previous district courts. In Justice of the Peace courts, lay justices of the peace work with a legally qualified clerk of court who gives advice on law and procedure. Justices of the peace handle minor criminal matters.

History

The head of the judiciary in Scotland is the Lord President of the Court of Session[2] whose office dates back to 1532 with the creation of the College of Justice.[3] Scotland's judiciary was historically a mixture of feudal, local, and national judicial offices. The first national, royal, justices were the justiciars established in the 12th century; with there being either two or 3 appointed. The justiciars and their deputes would go on circuit to hear the most serious of cases that could not be heard by the local feudal or sheriff courts,[4][5] in a comparable (but not identical) manner to Assizes in England. In the Middle Ages, many Scots were subject to the local feudal lords, with only treason reserved to the royal courts. These feudal jurisdictions, called heritable jurisdictions, were abolished in 1747 by the Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746.[6]

The sheriff courts developed in the Middle Ages as royal courts to challenge the authority of the local feudal courts, though the office of sheriff became itself a heritable jurisdiction with a legally qualified sheriff-depute the effective judge.[4][6] The jurisdiction of the sheriffs was re-organised into twelve sheriffdoms following the passage of the Sheriff Courts (Scotland) Act 1870[7] The number of sheriffdoms was reduced to six in 1975, with only minor changes to the territorial extent of each sheriffdom since then.[8]

Locally administered courts continued until the replacement of the district courts by justice of the peace courts in 2008,[9] and now all Scottish courts are administered centrally, with all judges, except the Lord Lyon and the justices of the peace, appointed on the recommendation of the Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland.[10][11] Due to the volume of business, some legally qualified stipendiary magistrates sat in Glasgow, when following the Court Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 the office of stipendiary magistrate was abolished, and several stipendiary magistrates became summary sheriffs.[12]

Today, the Scottish judiciary are divided into the Senior Judges, the Senators of the College of Justice, the Chairman of the Scottish Land Court, the Lord Lyon, the Sheriffs Principal, the Appeal Sheriffs, Sheriffs, Part-time Sheriffs, Summary Sheriffs, Part-Time Summary Sheriffs, Justices of the Peace, and Tribunal Judges.

Judicial officer holders

Lord President of the Court of Session

The Lord President of the Court of Session is the head of the country's judiciary and the presiding judge of the College of Justice (which comprises the Court of Session and High Court of Justiciary.) The current Lord President is Lord Carloway, who was appointed in December 2015 having previously served as Lord Justice Clerk[13] When presiding over criminal cases in the High Court of Justiciary the Lord President is known as the Lord Justice-General, an office that can be traced back to the ancient justiciars. In 1830, the Court of Session Act 1830 united the offices of Lord President of the Court of Session and Lord Justice General, with the person appointed as Lord President assuming the office of Lord Justice General ex officio.[14]

The Lord President presides over the 1st Division of the Inner House of the Court of Session, and will often hear appeals that raise significant or important points of law.[15]

The Lord President was made head of a unified judiciary as a result of the passage of the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 by the Scottish Parliament. In his role as Head of the Judiciary he is supported by the Judicial Office for Scotland, and the Lord President chairs the corporate board of the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service.[16] The Judicial Office is administered by an executive director of the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service.[17] The Lord President, and the wider judiciary, is advised on matters relating to the administration of justice by the Judicial Council for Scotland, which is a non-statutory body established in 2007. There had been plans for a statutory judges' council but these plans were abandoned in favour of a non-statutory council convened by the Lord President.[18][19][20]

Lord Justice Clerk

The Lord Justice Clerk is the second most senior judge in Scotland, after the Lord President of the Court of Session.[21] The Lord Justice Clerk presides over the 2nd Division of the Inner House of the Court of Session.[15] The current Lord Justice Clerk is Lady Dorrian, who was appointed to the position on 13 April 2016.[22]

The office of Lord Justice Clerk can be traced back to the clerk of court to King's Court, later the Justiciary Court, which was normally the responsibility of the Justiciar. The Justiciar normally appointed several deputes to assist in the administration of justice, and to preside in his absence. The clerk was legally qualified and advised the Justiciar and his deputes on the law, as they were generally noblemen without any legal education or experience as practising lawyers. This clerk prepared all the indictments and was keeper of the records. Eventually the influence of the clerk increased until the clerk gained both a vote in the court, and a seat on the bench as the Justice-Clerk.[23][24] When the High Court of Justiciary was established in its modern form by the Courts Act 1672, the position of the Lord Justice Clerk was given a statutory basis.[25] The Lord Justice-General was president of the Court, and the Justice-Clerk vice-president. During the period when the office of Lord Justice-General was held by noblemen the Lord Justice-Clerk was virtual head of the Justiciary Court.[23]

Senators of the College of Justice

The Senators of the College of Justice are judges of the College of Justice and sit in either the Court of Session (where they are known as Lords of Council and Session[26]) or the High Court of Justiciary (where they are known as Lords Commissioners of Justiciary.) The Chairman of the Scottish Land Court ranks as a Senator but is always referred to by his judicial office.[27] Whilst the High Court and Court of Session historically maintained separate judiciary, these are now one and the same, and the term, Senator, is almost ordinarily used in referring to the judges of these courts.[28] When a Senator sits as judge in the Outer House of the Court of Session they are referred to as a Lord Ordinary.[29]

Ten senators will sit in the Inner House of the Court of Session, where they will hear appeals against decisions made by the Outer House, the Sheriff Appeal Court, or judgments made by a sheriff principal. The remaining senators will sit as judges of the Outer House. Additional duties include a senator being appointed as President of Scottish Tribunals, or Chairman of the Scottish Law Commission.[30][31]

To be eligible for appointment as a senator a person must have served at least 5 years as sheriff or sheriff principal, been an advocate for 5 years, a solicitor with 5 years rights of audience before the Court of Session or High Court of Justiciary, or been a Writer to the Signet for 10 years (having passed the exam in civil law at least 2 years before application.)[31][32]

Under the Treason Act 1708 it is treason to kill any of the Senators of the College of Justice when they are sitting in judgment and in exercise of their office.[33]

Chairman of the Scottish Land Court

The chairman of the Scottish Land Court, who is also appointed as president of the Lands Tribunal for Scotland, has the same rank and tenure as a senator of the College of Justice, but does not number as a member of the College of Justice. The office of chairman was created with the founding of the Scottish Land Court in 1991 by the Small Landholders (Scotland) Act 1911 which has a responsibility for hearing cases relating to agricultural tenancies and crofting. The chairman is supported by a deputy chairman who holds the office of sheriff.[34][35] The chairman is legally qualified, and must satisfy the same eligibility criteria as a senator: that is, they must have served at least 5 years as sheriff or sheriff principal, been an advocate for 5 years, a solicitor with 5 years rights of audience before the Court of Session or High Court of Justiciary, or been a Writer to the Signet for 10 years (having passed the exam in civil law at least 2 years before application.)[36]

When founded, the Scottish Land Court, and its judiciary, were a separate administration to the Court of Session, High Court of Justiciary and sheriff courts. The enactment of the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 sought to create a unified judiciary for Scotland, and so The Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 (Scottish Land Court) Order 2017 transferred responsibility for the administration of the court to the Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service, and made the chairman and deputy chairman part of the unified Scottish judiciary under the Lord President.[37]

The current chairman of the Scottish Land Court is Lord Minginish who was appointed by the monarch on 1 October 2014, having previously served as deputy chairman. His nomination by First Minister Alex Salmond was made following a recommendation of the Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland. At the same time he was also appointed by the Scottish Ministers as president of the Lands Tribunal for Scotland.[38]

Sheriffs principal

The sheriffs principal are responsible for the efficiency of administration of the courts within their sheriffdom (both the sheriff courts and the justice of the peace courts),[39] and since 1975 there have been 6 sherrifdoms in Scotland.[8] Sheriffs principal chair the Local Criminal Justice Boards, which bring together the local procurator fiscal, Police Scotland and Community Justice Authority, and Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service.[40] The sheriffs principal also serve ex officio as Commissioners of the Northern Lighthouse Board.[41]

To be eligible for appointment as a sheriff principal a person must be legally qualified as either an advocate or solicitor for at least 10 years.[32][42]

Sheriffs principal will preside over fatal accident inquiries brought under the Inquiries into Fatal Accidents and Sudden Deaths etc. (Scotland) Act 2016 with significant public interest.[39]

Sheriff officers are appointed by the sheriffs principal upon petition and the sheriff principal will investigate, and inspect, fitness for office under Part V of the Debtors (Scotland) Act 1987[43] and Section 8 of Act of Sederunt (Messengers-at-Arms and Sheriff Officers Rules) 1988.[44]

| Sheriffdom | Sheriff Principal | Main Court |

|---|---|---|

| Glasgow and Strathkelvin | Sheriff Principal Craig Turnbull | Glasgow Sheriff Court |

| Grampian, Highland and Islands | Sheriff Principal Derek Pyle | Inverness Sheriff Court |

| Lothian and Borders | Sheriff Principal Mhairi M. Stephen QC | Edinburgh Sheriff Court |

| North Strathclyde | Sheriff Principal Duncan L. Murray | Paisley Sheriff Court |

| South Strathclyde, Dumfries and Galloway | Sheriff Principal Aisha Anwar | Airdrie Sheriff Court |

| Tayside, Central and Fife | Sheriff Principal Marysia Lewis | Perth Sheriff Court |

Appeal sheriffs

Appeal sheriffs sit in the Sheriff Appeal Court and hear appeals against summary criminal proceedings, and some civil proceedings, from both the sheriff courts and justice of the peace courts. All sheriffs principal are automatically ex officio appeal sheriffs. They usually sit in a bench of 2 or 3 judges. Appeal sheriffs also hear appeals in civil cases that previously went to the sheriff principal. Decisions of the Sheriff Appeal Court may only be appealed to the High Court of Justiciary with the permission of the High Court.[46][47]

To be eligible for appointment as an appeal sheriff a person must have served at least 5 years as a sheriff.[48]

Sheriffs

Sheriffs deal with the majority of civil and criminal court cases in Scotland, with the power to preside in solemn proceedings with a jury of 15 for indictable offences and sitting alone in summary proceedings for summary offences. The maximum sentencing power of sheriff in summary proceedings is 12 months imprisonment, or a fine of up to £10,000. In solemn proceedings the maximum sentence is 5 years imprisonment, or an unlimited fine.[49]

The sheriff has exclusive jurisdiction for all civil claims under £100,000, with shared jurisdiction over all other civil proceedings with the Court of Session. There is no upper limit to the size of case handled by a sheriff, with almost all family actions taking place in the sheriff court.[49][50]

Sheriffs also preside over fatal accident inquiries which are convened to examine the circumstances around sudden or suspicious deaths, including those who die in the course of employment, in custody, or in secure accommodation.[51][52]

A sheriff must be legally qualified, and been qualified as an advocate or solicitor for at least 10 years.[49]

The office of sheriff (historically, sheriff-substitute or sheriff depute) evolved as a legally qualified person appointed by the hereditary sheriff principal (historically, sheriff). The hereditary office was abolished by the Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746.[6] The offices were officially renamed by section 4 of the Sheriff Courts (Scotland) Act 1971.[53]

Summary sheriffs

Summary sheriffs hear civil cases brought under Simple Procedure and criminal cases brought under summary proceedings. Their sentencing powers are identical to a sheriff sitting in summary proceedings.[54]

To be eligible for appointment as a summary sheriff a person must be legally qualified as either an advocate or solicitor for at least 10 years.[32][42]

The office of summary sheriff was established by the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014.[55]

Justices of the Peace

The justices of the peace primary role is to preside over summary criminal trials for driving offences (including careless driving, speeding, tachograph offences, and driving without a license), less serious assaults, breach of the peace, theft and other less serious common law offences. The maximum sentencing power of a justice of the peace is 60 days imprisonment, or a fine up to £2,500, or both, and the ability to disqualify drivers.[56] Justices of the peace are lay people (not legally qualified), and are advised by a lawyer who acts as legal adviser or clerk of court.[57]

The office of justice of the peace in Scotland can be traced back to 1609, when they were introduced by the Parliament of Scotland under James VI and I, as an alternative source of judicial authority to the sheriffs.[58] The sheriffs at this time were a heritable jurisdiction, which presented a perceived challenge to royal authority. Justices of the peace in Scotland have always had a limited jurisdiction and limited prestige: constantly overshadowed by the sheriff.[59]

Justices of the peace did, historically, have administrative functions such as regulating wages and contracts of servants and labourers, the maintenance of bridges, recruitment of militia, and special tax assessments. The office went into decline in the 19th century, and was revived by the establishment of the district courts in 1975.[59][60] The current system of justice of the peace courts was established in 2007 by the Criminal Proceedings etc. (Reform) (Scotland) Act 2007.[9]

Judicial independence

Judicial independence from the government, legislature and public prosecutor in Scotland in guaranteed in statute by the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008[61] which places a duty on the Scottish Ministers, the First Minister of Scotland, the Lord Advocate, and Members of the Scottish Parliament to uphold judicial independence and bars influences of the judiciary through special access. Judges swear a judicial oath which affirms their personal commitment to independence:[62]

“I will do right to all manner of people after the laws and usages of this realm, without fear or favour, affection or ill-will.”

— Judicial oath, Judicial Office for Scotland

The Scottish Government began consulting on how to ensure judicial independence in 2006 and the consultation resulted in the Lord President being recognised as the head of the Scottish judiciary, the transfer of the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service to judicial control, and the statutory basis for the Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland.[63]

The Lord President, Lord Justice Clerk, Senators of the College of Justice, Chairman of the Scottish Land Court, Sheriffs Principal, Sheriffs and Summary Sheriffs all hold office until retirement or until removal from office due to being unfit. They can only be removed from office for being unfit following a report from an independent tribunal, and subject to the oversight of the Scottish Parliament.

Judicial independence is also secured through a prohibition on permanent judges (no matter what office) from undertaking paid employment, and on restrictions as to the work that part-time or temporary judges can undertake. Generally, part-time and temporary judges will be practising advocates or solicitors, but they are prohibited from employment with the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service or the Government Legal Service for Scotland. Permanent judges are also barred from having any involvement with political parties or organisations.[64][32]

Judges may also not be sued or prosecuted for the work they carry out as a judge.[65]

Judicial independence was attested as early at 1599 when Lord President Seton addressed the King and said, "but this is a matter of law, in which we are sworn to justice according to our conscience and the statutes of the realm."[66]

Judicial appointment

Eligibility

To be eligible for appointment as a sheriff principal, sheriff, or summary sheriff (whether permanent, temporary, or part-time) a person must be legally qualified as either an advocate or solicitor for at least 10 years. To be eligible for appointment as a senator a person must have served at least 5 years as sheriff or sheriff principal, been an advocate for 5 years, a solicitor with 5 years rights of audience before the Court of Session or High Court of Justiciary, or been a Writer to the Signet for 10 years (having passed the exam in civil law at least 2 years before application.)[31][32][42]

Some sheriffs with five or more years’ service as a sheriff, are eligible to be appointed as Appeal Sheriffs to sit in the Sheriff Appeal Court.[48]

Judicial Appointments Board

Appointments to all offices of the judiciary, except for Lord Lyon and justices of the peace, are made by the First Minister of Scotland on the recommendation of the Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland. The statutory basis for making recommendations was established by the Scottish Parliament through Sections 9 to 27 of the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 (as amended by the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014). The 2008 Act established the requirements for making appointments of permanent, temporary and part-time judges.[10][67]

The appointment of sheriffs principal (permanent and temporary), sheriffs and summary sheriffs (permanent and part-time) is regulated by the Judiciaty and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 and the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014, which replaced the previous rules established by the Sheriff Courts (Scotland) Act 1971.[42][10][67]

Justice of the peace advisory committees

Justices of the peace are appointed by the First Minister on the recommendation of Justice of Peace Advisory Committees, which are established for each sheriffdom. Each sheriff principal is responsible for appointing members to the advisory committee for his or her sheriffdom, with each committee having at least 3 lay members, and no more than one sheriff.[68][69]

Lord Advocate

Historically appointments were made on the advice of the Lord Advocate, which in 1999 raised questions of judicial independence from the executive.[70][71] A conviction was overturned by the High Court of Justiciary Appeal Court on the grounds that a temporary sheriff was not independent in terms of Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights as he was appointed by the Lord Advocate for 1 year, and could be dismissed at will. Given that the Lord Advocate is also the chief public prosecutor for Scotland this meant the sheriff could be concerned about making a judgment that could see them removed from office.[72] The Bail, Judicial Appointments etc. (Scotland) Act 2000 abolished the office of temporary sheriff and replaced it with part-time sheriffs who were appointed for a period of 5 years, and they cannot not be dismissed unless they are found unfit for duty by an independent tribunal.[73]

The role of the Lord Advocate in judicial appointments was removed by the establishment of the Judicial Appointments Board in 2002,[74] and was abolished in statue by the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008.[10]

Tenure

The Lord President, Lord Justice Clerk, Senators of the College of Justice, and all permanent sheriffs principal, sheriffs and summary sheriffs, hold office until compulsory retirement unless they are removed from office for inability, neglect of duty, or misbehaviour.

College of Justice

The Lord President, Lord Justice Clerk, and Senators (including the Chairman of the Scottish Land Court) are subject to a retirement age of 75.[75] The judges of the College of Justice and the Chairman of the Scottish Land Court can only be removed from office should the Scottish Parliament resolve that the First Minister makes a recommendation to His Majesty the King. Such a recommendation can only be made after a tribunal has been convened to investigate the matter and reported on the need for removal from office. The tribunal is convened on the request of the Lord President, or in other circumstances that the First Minister sees fit. However, the First Minister must consult the Lord President (for all other judges) and the Lord Justice Clerk (when the Lord President is under investigation.)[76][65]

Sheriffs principal and sheriffs

Historically sheriffs were said, after seven years, to hold their office Ad vitam aut culpam (for life or until fault) meaning that they could only be only removed from office for "gross misbehaviour or neglect of duty". Ad vitam aut culpam was enacted by Section 29 of the Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746,[77] however this was modified by the Sheriff Courts (Scotland) Act 1971 which allowed for the Lord President and Lord Justice Clerk to investigate the fitness for office of any sheriff principal or sheriff, and by Section 2 of the Judicial Pension Act 1959 which enforced compulsory retirement at the age of 75.[78] This was subsequently modified to the age of 70 by Section 26 of the Judicial Pensions and Retirement Act 1993.[75]

Fitness for office of sheriffs principal, sheriffs, and summary sheriffs (and their part-time equivalents) is decided by an ad-hoc tribunal constituted by the First Minister at the request of the Lord President, and such a tribunal will make a report. The power to convene this tribunal is granted by Section 21 of the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014. The First Minister must present the report to the Scottish Parliament and, should the report find that the judge unfit to hold office by "reason of inability, neglect of duty or misbehaviour" then the First Minister may dismiss the judge. If the judge is a permanent sheriff principal, sheriff, or summary sheriff then the First Minister must make an order subject to negative procedure.[79]

Part-time and temporary judges

Part-time and temporary judges, and Justices of the Peace, hold office for a period of 5 years, and may be reappointed provided they have not resigned, been dismissed, or reached the compulsory retirement age.[67][80][81]

Justices of the peace are subject to a procedure regulated by Section 71 of the Criminal Proceedings etc. (Reform) (Scotland) Act 2007, and are dismissed from office by order of the Lord President. A tribunal must be convened, and the tribunal is chaired by the Sheriff Principal of the sheriffdom in which the justice of the peace is a judge. The process for regulating these tribunals and the process of investigation is regulated by acts of sederunt. Once removed from office a justice of the peace cannot be reappointed.[82]

Judicial administration

Judicial Office for Scotland

The Lord President is supported by the Judicial Office for Scotland which was established on 1 April 2010 as a result of the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008, and the Lord President chairs the corporate board of the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service.[16] The Judicial Office is administered by an executive director of the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service.[17]

Judicial Council for Scotland

The Lord President and the wider judiciary are advised on matters relating to the administration of justice by the Judicial Council for Scotland, which is a non-statutory body established in 2007. There had been plans for a statutory judges' council but these plans were abandoned in favour of a non-statutory council convened by the Lord President.[18][19][20]

Judicial Institute for Scotland

The Lord President has delegated this responsibility to the Judicial Institute for Scotland, as the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 makes the Lord President responsible for the welfare, training, and guidance of all judicial office holders in Scotland. The Lord President is President of the Judicial Institute.[83] The Judicial Institute was established on 2 September 2013 after Lord Gill, Lord President at the time, signed the Governance Framework for the Judicial Institute; the governance of the institute is the responsibility of an advisory council as the statutory duty for training resides with the Lord President alone. The Lord President also appoints a chairman and vice-chairman of the advisory council, with a director appointed to undertake operational responsibility for the Judicial Institute.[84][85]

Formal judicial training started in Scotland in 1997 with the establishment of the Judicial Studies Committee, which initially dealt with training for the Court of Session, High Court of Justiciary, and sheriff courts. In 2007 it took on responsibility for the training of justices of peace.[86]

Justices' Training and Appraisal Committees

Each sheriffdom has a Justices' Training Committee and a Justices' Appraisal Committee as required by the Justices of the Peace (Scotland) Order 2007. The training committee is responsible for organising the training required for new and existing justices, and the appraisal committee is responsible for appraising the performance of justices. Should a justice fail in their appraisal in the appraisal committee has the authority to recommend remedial action.[68] The training for justices of the peace is determined by the Lord President, and is laid out in the Justices of the Peace (Training and Appraisal) Order 2016.[87]

Complaints

Complaints about the conduct of all judicial officer holders in Scotland are made to the Lord President through the Judicial Office for Scotland. The Judicial Office does not consider complaints about judicial decisions which are dealt with through appeals. Such complaints can relate to the conduct of the judge within and outwith the court.[88]

The process for making complaints is regulated by the Complaints About the Judiciary (Scotland) Rules 2017 which were made by the Lord President under section 28 of the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008.[89] The rules require a disciplinary judge to be appointed by the Lord President, to supervise the operation of the rules, and the Judicial Office to handle the complaint. Allegations of criminal conduct are outwith the scope of the complaints process.[90]

Should the investigation find against the judicial officer holder the Lord President has the power to give formal advice, a formal warning, or a reprimand.[91]

The Judicial Complaints Reviewer is a Scottish public ombudsman, established by section 30 of the Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008.[92] Her role is to review how complaints have been handled by the Judicial Office for Scotland, and to ensure that they have been dealt with in accordance with the rules. She cannot the review the outcome of the investigation, overturn a decision, or initiate redress. Where she finds a fault in the process she passes a referral to the Lord President who then makes decision.[93]

The current Judicial Complaints Reviewer, Ian Gordon, OBE, QPM, was appointed on 1 September 2017.[94] The previous Judicial Complaints Reviewer was Gillian Thompson, who began her tenure on 1 September 2014 until succeeded by the current reviewer.[95]

Addressing judges

How to address, either by writing or in person, a judge in Scotland depends on which office they hold, and if they are a Peer of the Realm or not.

Senior Judges

The Lord President and Lord Justice Clerk are always made Privy Counsellors, and are given a judicial title in addition to any peerage they may already hold. Their judicial title will begin Lord or Lady, but is not a peerage. In Court the Lord President, Lord Carloway, is addressed as my Lord, and the Lord Justice Clerk, Lady Dorrian, is addressed as my Lady.

| Office | Abbreviated title (in Law Reports, etc.) | Form of address in correspondence (if a Peer) | Form of address in correspondence (if not a Peer) | Salutation | Form of address in court |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lord President of the Court of Session[96] | Lord President[97] | The Right Honourable the Lord Smith Lord President of the Court of Session | The Right Honourable Lord Smith Lord President of the Court of Session | Dear Lord President | My Lord |

| Lord Justice General of Scotland[96] | Lord Justice General[98] | The Right Honourable the Lord Smith Lord Justice General of Scotland | The Right Honourable Lord Smith Lord Justice General of Scotland | Dear Lord Justice General | My Lord |

| Lord Justice Clerk[96] | Lord Justice Clerk[99] | The Right Honourable the Lady Smith Lord Justice Clerk | The Right Honourable Lady Smith Lord Justice Clerk | Dear Justice Clerk | My Lady |

Senators of the College of Justice

Senators of the College of Justice are given a judicial title with the courtesy title of Lord or Lady, but this should be distinguished from a peerage. Some Senators are also made Privy Counsellors. In court they are addressed as either my Lord or my Lady.[96]

| Office | Abbreviated title (in Law Reports, etc.) | Form of address in correspondence (if a Privy Counsellor and Peer) | Form of address in correspondence (if a Privy Counsellor) | Form of address in correspondence (if a Peer) | Form of address in correspondence (if not a Peer or Privy Counsellor) | Salutation | Form of address in court |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Senator of the College of Justice[96] | Lord/Lady Smith (of Territory) | The Right Honourable the Lord/Lady Smith | The Right Honourable Lord/Lady Smith | The Honourable the Lord/Lady Smith | The Honourable Lord/Lady Smith | Dear Lord President | My Lord/Lady |

Sheriffs Principal and Sheriffs

Sheriffs and sheriffs principal are always given a judicial title, and are always addressed by their judicial title. In court they are addressed as either my Lord or my Lady.

| Office | Abbreviated title (in Law Reports, etc.) | Form of address in correspondence (if a QC) | Form of address in correspondence | Salutation | Form of address in court |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheriff Principal[96] | Sheriff Principal Smith | Sheriff Principal Smith QC | Sheriff Principal Smith | Sheriff Principal Smith | My Lord/Lady |

| Sheriff[96] | Sheriff Smith | Sheriff Smith QC | Sheriff Smith | Sheriff Smith | My Lord/Lady |

Justices of the Peace

Justices of the Peace are not afforded a judicial title and will be addressed in correspondence by whatever personal or professional title they otherwise hold. In court they will be addressed as Your Honour.

| Office | Form of address in correspondence | Salutation | Form of address in court |

|---|---|---|---|

| Justice of the Peace[96] | Mr/Miss/Ms/Mrs etc. Smith | Mr/Miss/Ms/Mrs etc. Smith | Your Honour |

Historical judicial offices

There are several judicial offices which are no longer extant in Scotland, with their powers having either been subsumed into other offices, their jurisdiction abolished, or their office having fallen into abeyance.

Lord Chancellor of Scotland

The Lord Chancellor of Scotland was the first statutory President of the Court of Session when it was established in 1532 by the Parliament of Scotland. The Lord President of the Court of Session presided in the Lord Chancellor's absence, and when the Lord Chancellor was present sat as a Lord of Session.[100][101][102]

Extraordinary Lords of Session

Extraordinary Lords of Session were members of the Court of Session who were appointed as lay members, and were not required to have any legal education or experience of the law. In 1532 the number of Extraordinary Lords was fixed at 4. The power to appoint them lay with monarch of Scotland, and later the monarch of the United Kingdom.[101] The practice of appointing Extraordinary Lords ceased in 1721, and the office of Extraordinary Lord was abolished by the Section 2 of the Court of Session Act 1723. Section 1 of the same restated that Ordinary Lords of Session should be legally qualified.[103][104]

Barons of Exchequer

The Exchequer Court (Scotland) Act 1707 established the Court of Exchequer in Scotland, with Barons of Exchequer who acted in both a judicial capacity, dealing with revenue cases, debts to the crown, seizure of smuggled goods and prosecutions for illicit brewing and distilling, and in an administrative capacity, mainly auditing accounts. The president of the Exchequer Court was known as the Chief Baron of Exchequer, and the initial president was the Lord High Treasurer. The 1707 Act limited the numbers of Barons to five.[105][106] A separate Exchequer Court was abolished by the Exchequer Court (Scotland) Act 1856, and all of its powers were transferred to the Court of Session. With its abolishment no further Barons of Exchequer were appointed.[107]

Stipendiary magistrates

Stipendiary magistrates, magistrates in receipt of a stipend, were the most junior judges in the Scottish judiciary, until the passage of the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014. As of 2014 there were only 4.9 full-time equivalent posts and the only court they sit in was the Justice of the Peace Court in Glasgow. The Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014, passed by the Scottish Parliament, abolished the post with the creation of the new post of summary sheriff.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ "Scottish Budget Draft Budget 2014-15". Scottish Government. p. 7. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

Courts, Judiciary and Scottish Tribunal Service

- ↑ "Section 2, Paragraph 1, Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008", Acts of the Scottish Parliament, vol. 2008, no. 6, p. 2(1), retrieved 29 August 2009,

The Lord President is the Head of the Scottish Judiciary.

- ↑ Lord Hope of Craighead (20 October 2008). "King James Lecture – "The best of any Law in the world" – was King James right?" (PDF). United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- 1 2 Barrell, A.D.M. (2009). Medieval Scotland (Digital print. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Pr. p. 34. ISBN 978-0521586023. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. Accessed on 1 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Heritable jurisdictions - Oxford Reference". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. 2009. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ↑ "The Public general statutes, Volume 5" (eBook). archive.org. pp. 538–541. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

An Act to amend and extend the Act sixteenth and seventeenth Victoria, chapter ninety-two, to make further provision for uniting counties in Scotland in so far as regards the jurisdiction of the Sheriff..

- 1 2 Statutory Instrument 1974 No. 2087 The Sheriffdoms Reorganisation Order 1974 (Coming into force 1 January 1975)

- 1 2 "Section 59 of the Criminal Proceedings etc. (Reform) (Scotland) Act 2007 (asp 6)". Office of Public Sector Information. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

The Scottish Ministers may by order establish courts of summary criminal jurisdiction to be known as justice of the peace courts.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sections 9 to 18, Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

The judicial offices within the Board's remit are— (a)the office of judge of the Court of Session, (b)the office of Chairman of the Scottish Land Court, (c)the office of temporary judge (except in any case where the individual to be appointed to the office holds or has held one of the offices mentioned in subsection (2)), (d)the office of sheriff principal, (e)the office of sheriff, (f)the office of part-time sheriff, F1... [F2(fza)the office of summary sheriff, (fzb)the office of part-time summary sheriff,] [F3(fa)the positions within the Scottish Tribunals mentioned in subsection (2A), and]

- ↑ "Role and Remit of the Board | Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland". www.judicialappointments.scot. Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland. 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

The role of the Board is to recommend to the Scottish Ministers individuals for appointment to judicial offices within the Board's remit and to provide advice to Scottish Ministers in connection with such appointments.

- 1 2 "Summary Sheriffs". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2017. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

The 2014 Act also abolished the office of stipendiary magistrate...Part-time stipendiary magistrates will become part-time summary sheriffs from 1 April: J Kevin Duffy, Colin Dunipace, J Euan Edment, Sukhwinder Gill, David Griffiths, Diana McConnell.

- ↑ "Lord Carloway confirmed as next Lord President: The Journal Online". www.journalonline.co.uk. Law Society of Scotland. 18 December 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

Lord Carloway, the Lord Justice Clerk, has been appointed as Lord President of the Court of Session and Lord Justice General, it was confirmed this morning.

- ↑ "Court Of Session Act 1830", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1830 c. 69

- 1 2 "About the Court of Session". www.scotcourts.gov.uk. Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

The Inner House is in essence the appeal court, though it has a small range of first instance business. It is divided into the First and the Second Divisions, of equal authority, and presided over by the Lord President and the Lord Justice Clerk respectively.

- 1 2 "Schedule 3 of Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- 1 2 "SCTS Executive Team". www.scotcourts.gov.uk. Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

Executive Director Judicial Office | While a member of the Executive team, he is accountable to the Lord President for the functions of the Judicial Office.

- 1 2 Scottish Government (8 February 2006). "Strengthening Judicial Independence in a Modern Scotland - Chapter 4 - Judges' Council". www.gov.scot. The Scottish Government. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- 1 2 "Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Bill - Policy Memorandum" (PDF). parliament.scot. The Scottish Parliament. 30 January 2008. p. 7. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- 1 2 "Constitution of the Judicial Council for Scotland" (PDF). judiciary-scotland.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

The Judicial Council for Scotland ("the Council") is a body constituted for the purpose of providing information and advice to— (a) the Lord President of the Court of Session ("the Lord President"); and (b) the judiciary of Scotland, on matters relevant to the administration of justice in Scotland.

- ↑ "Lady Dorrian named as next Lord Justice Clerk: The Journal Online". www.journalonline.co.uk. Law Society of Scotland. 13 April 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

Court of Session and High Court judge Lady Dorrian has been appointed Lord Justice Clerk, the second most senior judge in Scotland.

- ↑ McArdle, Helen (13 April 2016). "Scotland appoints first female Lord Justice Clerk". The Herald. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- 1 2 Keedy, Edwin R. (1 January 1913). "Criminal Procedure in Scotland". Journal of the American Institute of Criminal Law and Criminology. 3 (5): 728–753. doi:10.2307/1132916. JSTOR 1132916.

- ↑ Pearson, Charles (October 1896). "The Administation [sic] of Criminal Law in Scotland". The American Law Register and Review. 44 (10): 619–632. doi:10.2307/3305421. JSTOR 3305421.

- ↑ "Courts Act 1672 (as enacted)". Records of the Parliaments of Scotland. University of St Andrews. 1672. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "Act of Sederunt (Rules of the Court of Session 1994) 1994". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 5 September 1994. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

The Lords of Council and Session, under and by virtue of the powers conferred on them by section 5 of the Court of Session Act 1988(1),

- ↑ "Overview [About: The Scottish Land Court]". www.scottish-land-court.org.uk. Scottish Land Court.

The Court has a Chairman who has the status of a judge of the Court of Session, and a Deputy Chairman who is a sheriff.

- ↑ "Senators of the College of Justice - Judicial Office Holders - About the Judiciary - Judiciary of Scotland". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2017. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ "About the Court of Session". www.scotcourts.gov.uk. Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

The Outer House consists of 22 Lords Ordinary sitting alone or, in certain cases, with a civil jury.

- ↑ Court of Session Act 1988: "Part V Appeal and Review". Office of Public Sector Information. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- 1 2 3 "The Office of Senator of the College of Justice". www.judicialappointments.scot. Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland. March 2016. Archived from the original (DOC) on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Eligibility for Judicial Appointment | Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland". www.judicialappointments.scot. Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland. 2016. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "Section XI of Treason Act 1708". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 1708. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ "Small Landholders (Scotland) Act 1911", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1911 c. 49

- ↑ "Welcome | Scottish Land Court". scottish-land-court.org.uk. Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ↑ "Office of the Chair of the Scottish Land Court | Judicial Office for Scotland". scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ↑ Scottish Parliament. The Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 (Scottish Land Court) Order 2017 as made, from legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ "Land Court and Lands Tribunal appointment" (Press release). Edinburgh: Scottish Government. 12 September 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- 1 2 Judicial Office for Scotland (March 2016). "The Office of Sheriff Principal". www.judicialappointments.scot. Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ Scottish Government (3 April 2006). "Local Criminal Justice Boards". www.gov.scot. Scottish Government. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ "Schedule 8 of Merchant Shipping Act 1995". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 19 July 1995. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sheriff Courts (Scotland) Act 1971". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 27 July 1971. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "Part V of Debtors (Scotland) Act 1987". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 15 May 1987. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "Act of Sederunt (Messengers-at-Arms and Sheriff Officers Rules) 1988". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 29 November 1988. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "Sheriffs Principal - Judicial Office Holders - About the Judiciary - Judiciary of Scotland". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ↑ Agency, The Zen (30 October 2015). "An overview of the new Sheriff Appeal Court". www.bto.co.uk. BTO Solicitors LLP. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ McCallum, Frazer (1 June 2016). "The Scottish Criminal Justice System:The Criminal Courts" (PDF). parliament.scot. Scottish Parliament Information Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- 1 2 "Appeal Sheriffs - Judicial Office Holders - About the Judiciary - Judiciary of Scotland". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

Some sheriffs with five or more years' service as a sheriff, are appointed as Appeal Sheriffs to sit in the Sheriff Appeal Court.

- 1 2 3 "Sheriffs - Judicial Office Holders - About the Judiciary - Judiciary of Scotland". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2017. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ Judicial Office for Scotland. "The Office of Sheriff". www.judicialappointments.scot. Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland. p. 6. Archived from the original (DOC) on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

23) A sheriff has exclusive competence to deal with civil proceedings where the total value of the orders sought does not exceed £100,000.

- ↑ "Fatal Accidents and Sudden Deaths Inquiry (Scotland) Act 1976". Legislation.gov.uk. 13 April 1976. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ↑ Judicial Office for Scotland. "The Office of Sheriff". www.judicialappointments.scot. Judicial Appointments Board for Scotland. p. 9. Archived from the original (DOC) on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

34) The sheriff is required to make certain findings and is empowered to make recommendations to avoid a recurrence of the incident.

- ↑ "Section 4 of Sheriff Courts (Scotland) Act 1971". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 27 July 1971. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "Summary Sheriffs - Judicial Office Holders - About the Judiciary - Judiciary of Scotland". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2017. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "Section 5 of Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 10 November 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "Justices of the Peace - Judicial Office Holders - About the Judiciary - Judiciary of Scotland". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2017. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "About Justice of the Peace Courts". www.scotcourts.gov.uk. Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

In court justices have access to advice on the law and procedure from lawyers, who fulfil the role of legal advisers or clerk of court.

- ↑ Davidson, Ian (2015). "The role of Justice of the Peace Court within the Scottish Legal System and the community" (PDF). poppyscotland.org.uk. The Scottish Prison Service. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- 1 2 Team, National Records of Scotland Web (2017). "National Records of Scotland". www.nrscotland.gov.uk. National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "District Courts (Scotland) Act 1975 (as enacted)". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 27 March 1975. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "Section 1 of Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "Judicial independence". judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ Scottish Government (8 February 2006). "Strengthening Judicial Independence in a Modern Scotland". www.gov.scot. The Scottish Government. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "FAQs - Help - Judiciary of Scotland". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2017. Archived from the original on 30 December 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- 1 2 "Judicial independence". judiciary-scotland.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ Tytler, Patrick Fraser (1843). History of Scotland, Volume 9 (eBook) (2 ed.). William Tait. p. 290. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Sections 6 to 11 of Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 10 November 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- 1 2 Scottish Parliament. The Justices of the Peace (Scotland) Order 2007 as made, from legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ "Justice of the Peace". www.gov.scot. The Scottish Government. 1 November 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "The constitutional position of the Lord Advocate: The Journal Online". www.journalonline.co.uk. Law Society of Scotland. 1 March 2000. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ Volkcansek, Mary L. (1 January 2009). "Exporting the Missouri Plan: Judicial Appointment Commissions". Missouri Law Review. 74 (3): 793. ISSN 0026-6604. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ Starrs and Chalmers v Ruxton, 1999 GWD 37-1793 (High Court of Justiciary Appeals Court 11 November 1999) ("appointment by the executive is consistent with independence only if it is supported by adequate guarantees that the appointed judge enjoys security of tenure. It is clear that temporary sheriff are appointed in the expectation that they will hold office indefinitely, but the control which is exercised by means of the one year limit and the discretion exercised by the Lord Advocate detract from independence").

- ↑ "Part 2 of Bail, Judicial Appointments etc. (Scotland) Act 2000". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 9 August 2000. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "Judicial Appointments: lessons from the Scottish experience" (PDF). parliament.uk. House of Commons. 30 June 2003. p. 6. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- 1 2 "Section 26 of Judicial Pensions and Retirement Act 1993". www.legislation.gov.uk. 29 March 1993. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ "Chapter 5 of Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ Stewart vs Secretary of State for Scotland, 1997-1998 SC (HL) (House of Lords 22 January 1998) ("section 29 of the Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746 which stated that a Sheriff Depute, after being in office for seven years, should hold the office "ad Vitam aut Culpam," and that a Sheriff Depute should only be deprived of his office for "gross Misbehaviour or Neglect of Duty" after a summary trial before the Court of Session.").

- ↑ "Section 2 of Judicial Pensions Act 1959". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 17 December 1959. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ "Sections 21 to 25 of Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 10 November 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ "Section 20B of Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 10 November 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ "Section 67 of Criminal Proceedings etc. (Reform) (Scotland) Act 2007". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 22 February 2007. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ "Section 71 of Criminal Proceedings etc. (Reform) (Scotland) Act 2007". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 22 February 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- ↑ "Judicial Training - About the Judiciary - Judiciary of Scotland". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ "Governance Framework for the Judicial Institute for Scotland" (PDF). scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2 September 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ "JI Advisory Council Members - Judicial Training - About the Judiciary - Judiciary of Scotland". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

The governing body of the Judicial Institute, known as the Advisory Council, meets quarterly and the Chairman, Director and Deputy-Director report on their work at every meeting.

- ↑ "UK: Scotland - EJTN Website". www.ejtn.eu. European Judicial Training Network. 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ↑ Scottish Parliament. The Justices of the Peace (Training and Appraisal) (Scotland) Order 2016 as made, from legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ "Complaints About Court Judiciary - You and the Judiciary - Judiciary of Scotland". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 (Section 28)". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "Complaints About the Judiciary (Scotland) Rules 2017" (PDF). scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 31 March 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 (Section 29)". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "Judiciary and Courts (Scotland) Act 2008 (Section 30)". www.legislation.gov.uk. The National Archives. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "How to complain". www.judicialcomplaintsreviewer.org.uk. Judicial Complaints Reviewer. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ↑ "About Us". Judicial Complaints Reviewer. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ↑ "New Judicial Complaints Reviewer appointed". The Scottish Government. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Addressing a Judge - You and the Judiciary - Judiciary of Scotland". www.scotland-judiciary.org.uk. Judicial Office for Scotland. 2017. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ↑ David MacMillan vs T Leith Developments Ltd (in receivership and liquidation), 2017 CSIH 23 (Inner House, Court of Session 10 March 2017) ("Lord President").

- ↑ HM Advocate vs Margo Robertson Alongi, 2017 HCJAC 18 (High Court of Justiciary Appeal Court 29 April 2016) ("Lord Justice General").

- ↑ Post Office Limited (Appellant) vs Assessor for Renfrewshire Valuation Joint Board (Respondent), 2010 CSIH 93 (Inner House, Court of Session 7 March 2017) ("Lord Justice Clerk").

- ↑ Lord Hope of Craighead (20 October 2008). "King James Lecture – "The best of any Law in the world" – was King James right?" (PDF). United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- 1 2 "College of Justice Act 1532 | Records of the Parliaments of Scotland". www.rps.ac.uk. University of St Andrews. 17 May 1532. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ↑ Bankton, Lord Andrew MacDowall (1752). An Institute of the Laws of Scotland in Civil Rights: With Observations Upon the Agreement Or Diversity Between Them and the Laws of England : After the General Method of the Viscount of Stair's Institutions. Stair Society. pp. 508–519. ISBN 978-1174517105. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ↑ Rayment, Leigh (30 December 2016). "Scottish Lords of Session". www.leighrayment.com. Leigh Rayment. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ "When the four present Extraordinary Lords of Session shall become vacant, no Presentation shall be made by the King to supply such Vacancy.": "Court of Session Act 1732". Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom No. 10 Geo. 1 XIX. of 9 October 1722.

- ↑ National Records of Scotland. "Exchequer Records". www.nrscotland.gov.uk. National Records of Scotland. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ↑ "Exchequer Court (Scotland) Act, 1707". Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom No. 6 Ann. XXVI. (53) of 23 October 1707.

- ↑ "The whole power, authority, and jurisdiction at present belonging to the Court of Exchequer in Scotland, as at present constituted, shall be transferred to and vested in the Court of Session, and the Court of Session shall be also the Court of Exchequer in Scotland": "Exchequer Court (Scotland) Act 1856". UK Statute Law Database. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

External links

- Official website

- National Records of Scotland -Exchequer Records Archived 9 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Open Government Licence v2.0. © Crown copyright.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the Open Government Licence v2.0. © Crown copyright.