.jpg.webp) Edinburgh, the financial centre of Scotland, the 4th largest financial centre in Europe and 13th largest internationally[1] | |

| Currency | Pound Sterling (£) |

|---|---|

| 1 April – 31 March | |

Trade organisations | WTO, OECD, AIIB, G-20 and G7 |

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

GDP growth | |

GDP per capita | |

GDP by sector | Agriculture: 1% Construction: 6% Production: 18% Services: 75% (2016 est.) |

Population below poverty line | |

Labour force | 2,457,000 (Dec 2023 est.)[7] |

Labour force by occupation | Public sector (22.1% March 2022)[9] Production Industry Agriculture Services |

| Unemployment | |

Average gross salary | £2,377 / €2,757 / $3,019 monthly (2023)[7] |

| £1,951 / €2,263 / $2,478 monthly (2023)[7] | |

Main industries | Fishing, Food & Drink, Forestry, Oil & Gas, Renewable Energy, Textiles, Tourism |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | Fish, Confectionery, Oil & Gas, Renewable Energy, Scotch Whisky, Textiles, Timber, Water |

Main export partners |

|

Main import partners | |

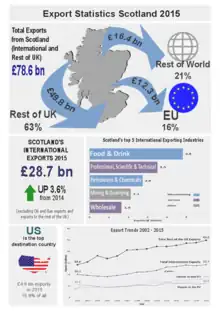

The economy of Scotland is an open mixed economy which, in 2023, had an estimated nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of £211.7 billion ($290 billion USD)[12] including oil and gas extraction in Scottish waters. Since the Acts of Union 1707, Scotland's economy has been closely aligned with the economy of the rest of the United Kingdom (UK), and England has historically been its main trading partner. Scotland still conducts the majority of its trade within the UK: in 2017, Scotland's exports totalled £81.4 billion, of which £48.9 billion (60%) was with the countries of the United Kingdom, £14.9 billion with the European Union (EU), and £17.6 billion with other parts of the world. Scotland’s imports meanwhile totalled £94.4 billion including intra-UK trade leaving Scotland with a trade deficit of £10.4 billion in 2017.

Scotland was one of the industrial powerhouses of Europe from the time of the Industrial Revolution onwards, being a world leader in manufacturing.[13] This left a legacy in the diversity of goods and services which Scotland produces, from textiles, whisky and shortbread to buses, computer software, ships, avionics and microelectronics, as well as banking, insurance, investment management and other related financial services. In common with most other advanced industrialised economies, Scotland has seen a decline in the importance of both manufacturing industries and primary-based extractive industries. This has, however, been combined with a rise in the service sector of the economy, which has grown to be the largest sector in Scotland.

The governments which involve themselves in Scotland's economy are largely the central UK Government (responsible for reserved matters via HM Treasury) and the Scottish Government (responsible for devolved matters). Their respective financial functions are headed by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, and the Cabinet Secretary for Finance. Since 1979, management of the UK economy (including Scotland) has followed a broadly laissez-faire approach.[14][15][16][17][18][19] The Bank of England is Scotland's central bank and its Monetary Policy Committee is responsible for setting interest rates. The currency of Scotland, as part of the United Kingdom, is the Pound sterling, which is also the world's fourth-largest reserve currency after the US dollar, the euro and Japanese yen.[20]

As one of the countries of the United Kingdom, Scotland is a member of the Commonwealth of Nations, the G7, the G20, the International Monetary Fund, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the United Nations.

Overview

General overview

.svg.png.webp)

After the Industrial Revolution in Scotland, the Scottish economy concentrated on heavy industry, dominated by the shipbuilding, coal mining and steel industries. Scottish participation in the British Empire also allowed Scotland to export its output throughout much of the world. However heavy industry declined in the late 20th century, leading to a shift in the economy of Scotland towards technology and the service sector. The 1980s saw an economic boom in the Silicon Glen corridor between Edinburgh and Glasgow, with many large technology firms relocating to Scotland.

Data released by the Scottish Government in 2023 found that there were a total of 149,992 establishments (a single site of an organisation), which employed a total of 2.46 million people in Scotland between each oganisation.[21] The largest employment industries in Scotland by March 2022 were the primary sector and utilities (5% of employment), manufacturing (7% of employment), construction (6% of employment), wholesale and retail (14% of employment), hotels and restaurants (8% of employment), transport and storage (4% of employment), information and communication (3% of employment), financial services (3% of employment), business services (16% of employment), public administration (6% of employment), the education sector (8% of employment) and health and social work (16% of employment).[21]

Scottish-based companies have strengths in information systems, defence, electronics, instrumentation and semiconductors. There is also a dynamic and fast growing electronics design and development industry, based around links between the universities and indigenous companies. There was a significant presence of global players like National Semiconductor and Motorola. Other major industries include banking and financial services, construction,[22] education, entertainment, biotechnology, transport equipment, oil and gas, whisky, and tourism. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of Scotland in 2013 was $248.5 billion including revenue generated from North Sea oil and gas.Edinburgh is the financial services centre of Scotland, with many large financial firms based there. Glasgow is the fourth-largest manufacturing centre in the UK, accounting for well over 60% of Scotland's manufactured exports. Shipbuilding, although significantly diminished from its heights in the early 20th century, is still a large part of the Glasgow economy. Aberdeen is the centre of North Sea offshore oil and gas production, with giants such as Shell and BP housing their European exploration and production HQs in the city. Other important industries include textile production, chemicals, distilling, agriculture, brewing and fishing.

Total public expenditure in Scotland in 1999/2000 was £36.4 billion, of which identifiable spending which can be proven to benefit Scotland was £27.4 billion. This increased to a total public expenditure of £100.4 billion in 2020/21 of which £81.1 billion was identifiable spending that can be proven to benefit Scotland.[23][24]

History

When Scotland ratified the 1707 Act of Union, Scotland's national debt was at zero, whereas England had totalled £20,000,000 in debt, taxes were low due to war avoidance, and trade thrived from industries such as tobacco, sugar, cotton and rice which enhanced Scotland's industrialisation through the 18th and 19th centuries.[25] Article 15 of the Treaty of Union Act 1707 stipulated that the Kingdom of England would pay the Kingdom of Scotland a lump sum of £398,085 10s, known as The Equivalent, which served as a means of compensation for Scotland taking on a share of England's debt.[26] As a consequence of the Act of Union, Scotland well–established trade links with France and the Low Countries was cut off abruptly. The economic benefits of Union which had been promised by proponents of the Act were slow to materialise, causing widespread discontent amongst the population. Despite their new status as citizens of the United Kingdom, it took many decades for Scottish traders to gain a noticeable foothold in the colonial markets which had long been dominated by English merchants and concerns. The economic effects of the Union on Scotland were negative until about 1715[27] mainly due to an increase in unpopular forms of taxation which increased the price of Scottish products which benefited manufacturers based in England,[27] such as the Malt Tax in 1712, as well as the introduction of duties on imports, which the Scottish exchequer had previously been neglectful in enforcing on most trade goods.[28] Eventually, the Union gave Scotland access to England's global marketplace, triggering an economic and cultural boom .[29] German sociologist Max Weber credited the Calvinist "Protestant Ethic", involving hard work and a sense of divine predestination and duty, for the entrepreneurial spirit of the Scots.[30]

Growth was rapid after 1700, as Scottish ports, especially those on the Clyde, began to import tobacco from the American colonies. Scottish industries, especially linen manufacturing, were developed. Scotland embraced the Industrial Revolution, becoming a small commercial and industrial powerhouse of the British Empire. Many young men built careers as imperial administrators. Many Scots became soldiers, returning home after 20 years with their pension and skills.[31]

From 1790 the chief industry in the west of Scotland became textiles, especially the spinning and weaving of cotton. This flourished until the American Civil War in 1861 cut off the supplies of raw cotton; the industry never recovered. However, by that time Scotland had developed heavy industries based on its coal and iron resources. The invention of the hot blast for smelting iron (1828) had revolutionised the iron industry, and Scotland became a centre for engineering, shipbuilding, and locomotive construction. Toward the end of the 19th century steel production largely replaced iron production. Emigrant Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) built the American steel industry, and spent much of his time and philanthropy in Scotland.[32] Agriculture gained after the union, and standards remained high. However the adoption of free trade in mid-19th century brought cheap American corn which undersold local farmers. The industrial developments, while they brought work and wealth, were so rapid that housing, town planning, and provision for public health did not keep pace with them, and for a time living conditions in some of the towns were notoriously bad.

Shipbuilding reached a peak in the early 20th century, especially during the Great War, but quickly went into a long downward slide when the war ended.[33] The disadvantage of concentration on heavy industry became apparent: other countries were themselves industrialising and were no longer markets for Scottish products. Within Britain itself there was also more centralisation, and industry tended to drift to the south, leaving Scotland as a neglected fringe. The entire period between the world wars was one of economic depression, of which the worldwide Great Depression of 1929–1939 was the most acute phase. The economy revived with munitions production during the Second World War. After 1945, however, the older heavy industries continued to decline and the government provided financial encouragement to many new industries, ranging from atomic power and petrochemical production to light engineering. The economy has thus become more diversified and therefore more stable.

COVID-19 impact

Like other international economies, the economy of Scotland had suffered loses in revenue as a result of temporary business closures resulted by the national lockdown implemented by the Scottish Government in March 2020. The Scottish Government announced that, based on economic predictions in 2020, that Scottish unemployment figures were expected to increase to 8.2% by the end of 2020. Many areas of the Scottish economy, such as production markets, began to operate at reduced capacity in an attempt to slow the spread of the virus, meaning that productions rates were slower than normal levels prior to the outbreak. The Scottish Government cautioned that Scotland's economic output could fall 9.8% in 2020, with global economic uncertainty remaining elevated.[34]

The tourism and hospitality sector has particularly suffered. In October 2020, the Scottish Tourism Alliance made this comment: "The devastating impact of this pandemic will make recovery incredibly challenging, if not questionable, without the assurance of continued targeted support from both the Scottish and UK Governments".[35] In a March 2021 speech, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon acknowledged the "acute challenges our tourism and hospitality sectors have faced".[36]

There have been suggestions that the economic impact as a result of the COVID-19 outbreak could permanently affect the economy of Scotland, similar to the way deindustrialization of Scotland's shipyards and coal production had a major, long-lasting effect on the economy during the 1980s.[37]

Exports of many food and drink products from the UK declined significantly,[38] including Scotch whisky. Distillers were required to close for some time and the hospitality industry worldwide experienced a major slump.[39] According to news reports in February 2021, the Scotch whisky sector had experienced £1.1 billion in lost sales. Exports to the US were also affected by the 25% tariff that had been imposed. Scotch whisky exports to the US during 2020 "fell by 32%" from the previous year. Worldwide exports declined by 70%.[40] A BBC News headline on 12 February 2021 summarized the situation: "Scotch whisky exports slump to 'lowest in a decade'".[41]

Primary industry

Agriculture and forestry

A very small proportion of Scotland's total land mass is classified as arable – circa 10% based on Scottish Government figures[42] Only about one quarter of the land is under cultivation – mainly in cereals. Barley, wheat and potatoes are grown in eastern parts of Scotland such as Aberdeenshire, Moray, Highland, Fife and the Scottish Borders. The Tayside and Angus area is a centre of production of soft fruits such as strawberries, raspberries and loganberries, owing to the climate. Sheep-raising is important in the less arable mountainous regions, such as the northwest of Scotland, which are used for rough grazing, due to its geographical isolation, poor climate and acidic soils. Parts of the east of Scotland (areas such as Aberdeenshire, Fife and Angus) are major centres of cereal production and general cropping. In such areas, the land is generally flatter, coastal, and the climate less harsh, and more suited to cultivation. The south-west of Scotland – principally Ayrshire and Dumfries and Galloway – is a centre of dairying. Agriculture, especially cropping in Scotland, is highly mechanised and generally efficient. Farms tend to cover larger areas than their European counterparts. Hill farming is also prominent in the Southern Uplands in the south of Scotland, resulting in the production of wool, lamb and mutton. Cattle rearing, particularly in the east and south of Scotland, results in the production of large amounts of beef. Farming in Scotland was affected by BSE and the European ban on the importation of British beef from 1996. Dairy and cattle farmers in south-west Scotland were affected by the 2001 UK Foot and Mouth outbreak, which resulted in the destruction of much of their livestock as part of the biosecurity effort to control the spread of the disease.

Because of the persistence of feudalism and the land enclosures of the 19th century the ownership of most land is concentrated in relatively few hands (some 350 people own about half the land). In 2003, as a result, the Scottish Parliament passed a Land Reform Act that empowered tenant farmers and communities to purchase land even if the landlord did not want to sell.[43]

As of 2019, a century since the founding of the Forestry Commission, about 18.5% of Scotland is forested.[44] The majority of forests are in public ownership, with forestry policy being controlled by Scottish Forestry. The biggest plantations and timber resources are to be found in Dumfries and Galloway, Tayside, Argyll and the Scottish Highlands. The economic activities generated by forestry in Scotland include planting and harvesting as well as sawmilling, the production of pulp and paper and the manufacture of higher value goods. Forests, especially those surrounding populated areas in Central Scotland, also provide a recreation resource.

Fishing

The waters surrounding Scotland are some of the richest in Europe. Fishing is an economic mainstay in parts of the North East of Scotland and along the west coast, with important fish markets in places such as Aberdeen and Mallaig. Fish and shellfish such as herring, crab, lobster, haddock and cod are landed at ports such as Peterhead, the biggest white fish port in Europe, Fraserburgh, the biggest shellfish port in Europe, Stornoway, Lerwick and Oban. There has been a large scale decrease in employment in the fishing industry within Scotland, due initially to the sacrifice of national fishing rights to the EEC on the UK's accession to the Common Market in the 1970s, and latterly to the historically low abundances of commercially valuable fish in the North Sea and parts of the North Atlantic. To rebuild stocks the EU's Common Fisheries Policy places restrictions on the total tonnage of catch that can be landed, on the days at sea allowed and on fishing gear that can be deployed.

In tandem with the decline of sea-fishing, commercial fish farms, especially in salmon, have increased in prominence in the rivers and lochs of the north and west of Scotland. Inland waters are rich in fresh water fish such as salmon and trout although here too there has been an inexorable and so far unexplained decline in abundance over the past decades.[45]

Mineral resources

Scotland has a large abundance of natural resources from fertile land suitable for agriculture, to oil and gas. In terms of mineral resources, Scotland produces coal, zinc, iron and oil shale. The coal seams beneath central Scotland, in particular in Ayrshire and Fife contributed significantly to the industrialisation of Scotland during the 19th and 20th centuries. The mining of coal – once a major employer in Scotland has declined in importance since the later half of the 20th century, due to cheaper foreign coal and the exhaustion of many seams. The last deep-coal mine was at Longannet on the Firth of Forth which closed in 2016.[46] A modest amount of opencast coal mining continues.

Fracking

"In October 2017 the Scottish Government announced a ban on fracking after a six year struggle that saw massive opposition to the industry across the country."[47] The Scottish Government states that it is taking a cautious, considered and evidenced-based approach to fracking. In January 2015 the Scottish Government placed a moratorium on granting consents for unconventional oil and gas extraction.[48] This will allow health and environmental impact tests to be carried out as well as a full public consultation to allow every interested organisation and any member of the public to input their views. The Scottish Government has stated that no fracking can or will take place in Scotland while the moratorium remains in place.

Oil and gas

Scottish waters consisting of a large sector of the North Atlantic and the North Sea, containing the largest oil resources in Western Europe – The UK is one of Europe's largest petroleum producers, with the discovery of North Sea oil transforming the Scottish economy. Oil was discovered in the North Sea in 1966, with the first year of full production taking place in 1976.[49] With the growth of oil exploration during that time, as well as the ancillary industries needed to support it, the city of Aberdeen became the UK's centre of the North Sea Oil Industry, with the port and harbour serving many oil fields off shore. Sullom Voe in Shetland is the site of a major oil terminal, where oil is piped in and transferred to tankers. Similarly the Flotta Oil Terminal in Orkney is linked by a 230 km long pipeline to the Piper and Occidental oil fields in the North Sea.[50] Grangemouth is at the centre of Scotland's petrochemicals industry. The oil related industries are a major source of employment and income in these regions. It is estimated that the industry employs around 100,000 workers (or 6% of the working population) of Scotland.

Although North Sea oil production has been declining since 1999, an estimated 920 million tonnes of recoverable crude oil remained in 2009. Over two and a half billion tonnes were recovered from UK offshore oil fields between the first North Sea crude coming ashore in 1975 and 2002,[51] with most oil fields being expected to remain economically viable until at least 2020. High oil prices have resulted in a resurgence of oil exploration, specifically in the North East Atlantic basin to the west of Shetland and the Outer Hebrides, in areas that were previously considered marginal and unprofitable.[52] The North Sea oil and gas industry contributed £35 billion to the UK economy (a little under 1% of GDP) in 2014 and is expected to decline in the coming years.[53]

Secondary sector

Heavy industry

Scotland's heavy industry began to develop in the second half of the 18th century. The Carron Company established its ironworks at Falkirk in 1759, initially using imported ore but later using locally sourced Ironstone. The iron industry expanded tenfold between 1830 and 1844.[54] The shipbuilding industry on the River Clyde increased greatly from the 1840s and by 1870 the Clyde was producing more than half of Britain's tonnage of shipping.[55] The heavy industries based around shipbuilding and locomotives went into severe decline after the Second World War.[56]

Light industry

Manufacturing in Scotland has shifted its focus, with heavy industries such as shipbuilding and iron and steel declining in their importance and contribution to the economy. It is generally argued that this has been in response to increasing globalisation and competition from low-cost producers across the world, which has eroded Scotland's comparative advantage in such industries over the later half of the 20th century. However, the decline in heavy industry in Scotland has been supplanted with the rise in the manufacture of lighter, less labour-intensive products such as optoelectronics, software, chemical products and derivatives as well as life sciences. The engineering and defence sectors employ around 30,000 people in Scotland. The principal companies operating in the sector include; BAE Systems, Rolls-Royce, Raytheon, Alexander Dennis, Thales, SELEX Galileo, Weir Group and Babcock. The decline of heavy industry resulted in a sectoral shift of labour. This led to smaller firms strengthening links with the academic community and substantial, industry-specific retraining programmes for the workforce.

Whisky

Whisky is probably the best known of Scotland's manufactured products. Exports have increased by 87% from 2003 to 2013 and it contributes over £4.25 billion to the UK economy, making up a quarter of all its food and drink revenues.[57] It is also one of the UK's overall top five manufacturing export earners and it supports around 35,000 jobs.[58] Principal whisky producing areas include Speyside and the Isle of Islay, where there are nine distilleries providing a major source of employment. In many places, the industry is closely linked to tourism, with many distilleries also functioning as attractions worth £30 million GVA each year.[59]

Textiles

Historically Scotland's export trade was based around animal hides and wool. This trade was firstly organised around religious centres such as Melrose Abbey.[60] The trade expanded towards long-established maritime bases for Scottish trade at Bruges and then Veere[61][62] in the Low Countries and at Elbląg and Gdańsk in the Baltic.[63]

During the 18th century, the trade in linen overtook that in wool, peaking at over 12 million yards produced in 1775.[64] Production remained in cottage industry units but the trading conditions were locked into the modern economy and gave rise to institutions such as the British Linen Bank. By 1770, Glasgow was the largest linen manufacturer in Britain.[65]

Cotton began to replace linen in economic importance during the 1770s, with the first mill opening in Penicuik in 1778.[66] The trade brought urbanisation of the population, including large numbers of migrants from the Highlands and from Ireland. The thread manufacturers Coats plc had its origin in that trade. In 1782, George Houston built what was then one of the largest cotton mills in the country in Johnstone.[67]

In modern times, knitwear and tweed are seen as traditional cottage industries but names like Pringle and Lyle & Scott have given Scottish knitwear and apparel a presence on the international market. Despite increasing competition from low-cost textile producers in SE Asia and the Indian subcontinent, textiles in Scotland is still a major employer with a workforce of around 22,000. Furthermore, the textiles industry is the seventh-largest exporter in Scotland accounting for over 3% of all Scottish manufactured products.[68]

Electronics

Silicon Glen is the phrase that was used to describe the growth and development of Scotland's hi-tech and electronics industries in the Central Belt through the 1980s and 1990s, analogous to the larger concentration of hi-tech industries in Silicon Valley, California. Companies such as IBM and Hewlett-Packard have been in Scotland since the 1950s being joined in the 1980s by others such as Sun Microsystems (now owned by Oracle). The IBM factory campus in Greenock was demolished in 2019/2020. IBM no longer manufacture any electronics in Scotland but instead provide consultancy services. 45,000 people are employed by electronics and electronics-related firms, accounting for 12% of manufacturing output. In 2006, Scotland produced 28% of Europe's PCs; more than seven per cent of the world's PCs; and 29% of Europe's notebooks.[69]

Two major game developers are based in Scotland; Rockstar North (previously DMA Design, famed for the Lemmings trilogy), who are best known as the creators of the Grand Theft Auto franchise, and Rockstar Dundee, best known for developing Crackdown 2.

Construction

Scotland builds around 21,000 to 22,000 new homes per year, about 1% of its existing dwelling stock. According to Property Wire, the number of new homes built in Scotland during 2018 reached over 20,000 for the first time in a decade, a rise of 15% in the previous year, official data indicates that the number of new homes built in Scotland were up 15% year-on-year.[70] In 2019 there were 21,805 new homes built according to the 'Housing Statistics for Scotland Quarterly Update', published on 10 March 2020. The home building industry in Scotland directly and indirectly contributed around £5 billion to the Scottish economy in 2006 – about 2% of GDP – greater than that of higher profile industries such as agriculture, fishing, electronics and tourism. The net value of new building and repairs, maintenance and improvements combined is just under £11.6 billion, which is about 4.5% of Scottish GDP.[22]

Tertiary and service industries

Financial services

Edinburgh was ranked 15th in the list of world financial centres in 2007, but fell to 37th in 2012, following damage to its reputation,[71] and in 2015 was ranked 71st out of 84.[72] Big financial institutions such as The Royal Bank of Scotland, the Bank of Scotland, Scottish Widows and Standard Life all have a presence in the city.

Centred primarily on the cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow, the financial services industry in Scotland grew by over 35% between 2000 and 2005.[73] The financial services sector employs around 95,000 people and generates £7bn or 7% of Scotland's GDP.[74]

By 2020, Edinburgh was ranked 17th in the world for its financial services sector, and 6th in Western Europe, according to the Global Financial Services Centres Index.[75]

Banking

Banking in Scotland has a long history, beginning with the creation of the Bank of Scotland in Edinburgh in 1695, and expanding greatly to support the trading developments of the 18th and 19th centuries. Retail banking services to individuals followed in the 19th century, on the trustee savings bank model pioneered by Rev. Henry Duncan .[76]

Scotland has four clearing banks: the Bank of Scotland, The Royal Bank of Scotland, the Clydesdale Bank and TSB Bank. The Royal Bank of Scotland expanded internationally to be the second-largest bank in Europe, the fourth largest in the world by market capitalisation in 2008, but collapsed in the 2008 financial crisis and had to be bailed out by the UK Government at a cost of £76 billion;[77] its new global headquarters in Edinburgh augmented the city's position as a major financial centre. Prior to the 2008 financial crisis Scotland ranked second only to London in the European league of headquarters locations of the 30 largest banks in Europe as measured by market value.[78][79]

Although the Bank of England remains the central bank for the UK Government, three Scottish clearing banks still issue their own banknotes: the Bank of Scotland, the Royal Bank of Scotland and the Clydesdale Bank. These notes are legal currency but have no status as legal tender, which does not exist in Scots' Law (neither have Bank of England banknotes in Scotland); but in practice they are accepted throughout Scotland and by some retailers in the rest of the UK.[80] The full range of Scottish bank notes commonly accepted are £5, £10, £20, £50 and £100. (See British banknotes for further discussion).

Investment, insurance and asset servicing

The first half of the 19th century brought the creation of many life assurance companies in Scotland, predominantly on the mutual model. By the 1980s there were nine members of the Association of Scottish Life Offices (the counterpart of the Life Offices Association) but these have demutualised and most were taken over.[81] Standard Life, based in Edinburgh, demutualised and has remained independent.[82]

Starting in 1873, with Robert Fleming's Scottish American Investment Trust,[83] a relatively broad stratum of Scots invested in international investment trust ventures. Around 80,000 Scots held foreign investment assets in the early 20th century.[84]

Nowadays Scotland is one of the world's biggest fund management centres with over £300bn worth of assets directly serviced or managed in the country.[85] Scottish fund management centres have a major presence in areas such as pensions, property funds and investment trusts, as well as in retail and private client markets. Similarly asset servicing on behalf of fund managers has become an increasingly important component of the financial services industry in Scotland, with Scottish-based companies providing expertise in securities servicing, investment accounting, performance measurement, trustee and depositary services and treasury services.

Software

The software sector in Scotland developed rapidly and in 2016 there were an estimated 40,226[86] people working in the digital economy across Edinburgh, Glasgow and Dundee. Scotland's history in manufacturing is being transferred into the software sector and this is attracting companies from around the world. Software companies developing in Scotland include Skyscanner, FanDuel, Amazon and a thriving fintech community.

Several universities are playing an important role by producing research in Computing Science, including the University of Edinburgh's School of Informatics. According to the REF 2014[87] assessment for computer science and informatics the School of Informatics has produced more world-leading and internationally excellent research (4* and 3*) than any other university in the UK.

Tourism

It is estimated that tourism accounts for 5% of Scotland's GDP. Scotland is a well-developed tourist destination with attractions ranging from unspoilt countryside, mountains and abundant history. The tourism economy and tourism related industries in Scotland support c. 196,000 in 2014 mainly in the service sector accounting for around 7.7% of employment in Scotland.[88] In 2014, over 15.5 million overnight tourism trips were taken in Scotland, for which visitor expenditure totalled £4.8 billion. Domestic tourists (those from the United Kingdom) make up the bulk of visitors to Scotland. In 2014, for example, UK visitors made 12.5 million visits to Scotland, staying 41.6 million nights and spending £2.9 billion. In contrast, overseas residents made 2.7 million visits to Scotland, staying 21.5 million nights and spending £1.8 billion. In terms of overseas visitors, those from the United States made up 15% of visits to Scotland, with the United States being the largest source of overseas visitors, and Germany (13%), France (7%), Australia (6%) and Canada (5%) following behind.[88]

Like all of the UK, Scotland was negatively impacted by the restrictions and lockdowns necessitated by the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism has particularly suffered.[35] A report published in March 2021 by the Fraser of Allander Institute at the University of Strathclyde indicated that in Scotland, there was "no sign of a trend reversal with more than 70% of businesses in the sector reporting lower turnover than usual".[89]

The Scottish Tourism Alliance Task Force published its recommendations in October 2020, with "Immediate Actions" for both the Scottish government and the UK government, including financial grants, the funding of marketing for the sector, and a "temporary removal of Air Passenger Duty to boost route competitiveness".[90] On 24 March 2021, the First Minister announced a £25 million tourism recovery programme "to support the industry for the next 6 months to two years".[91] Sturgeon also reminded the hospitality/tourism industry that the government had provided "over £129 million" in support "for this sector".[92]

Trade

Regional trade

Excluding intra UK trade, the European Union and the United States constitute the largest markets for Scotland's exports. In the 21st century, with the high rates of growth in many emerging economies of southeast Asia such as China, Thailand and Singapore, there was a drive towards marketing Scottish products and manufactured goods in these countries.[93]

Note: Revenues from North Sea oil and gas are not included in these figures.

International trade

| Destination | 2014 value[94] | 2016 value[95] | 2019 value[96] |

|---|---|---|---|

| By country | |||

| £47,785 million | £45,785 million | £52,040 million | |

| £3,985 million | £4,775 million | £6,025 million | |

| £1,860 million | £1,960 million | £2,920 million | |

| £1,880 million | £2,115 million | £2,720 million | |

| £1,845 million | £1,910 million | £2,370 million | |

| £1,125 million | £1,025 million | £1,445 million | |

| £605 million | £760 million | £1,270 million | |

| £1,200 million | £1,365 million | £1,100 million | |

| £815 million | £855 million | £1,035 million | |

| £565 million | £715 million | £850 million | |

| £445 million | £650 million | £740 million | |

| £455 million | £525 million | £730 million | |

| £670 million | £705 million | £705 million | |

| £405 million | £565 million | £700 million | |

| £720 million | £995 million | £695 million | |

| £530 million | £555 million | £685 million | |

| £875 million | £770 million | £640 million | |

| £445 million | £610 million | £640 million | |

| £370 million | £460 million | £620 million | |

| £395 million | £795 million | £595 million | |

| No Data | No Data | £445 million | |

| By world region | |||

| £12,035 million | £12,675 million | £16,395 million | |

| North America | £4,915 million | £5,385 million | £6,665 million |

| Asia | £3,135 million | £3,175 million | £3,860 million |

| Rest of Europe | £2,870 million | £2,845 million | £2,505 million |

| Middle East | £1,720 million | £1,660 million | £1,845 million |

| Africa | £1,590 million | £1,640 million | £1,430 million |

| Central and South America | £1,390 million | £1,575 million | £1,490 million |

| Australasia | £605 million | £810 million | £865 million |

| Unallocable | £865 million | No Data | No Data |

| Total | £28,235 million | £29,790 million | £35,055 million |

- ↑ Includes trade with

England, Northern Ireland and

England, Northern Ireland and  Wales, but excludes trade with British Overseas Territories or Crown Dependencies.

Wales, but excludes trade with British Overseas Territories or Crown Dependencies. - ↑ "These are exports of goods and services by Scottish companies to customers in the rest of the UK. The majority of these exports will be consumed or remain within the rest of the UK, for example electricity or service exports such as financial services. However some of these Scottish exports to the rest of the UK will feed into supply chains elsewhere in the rest of the UK and in turn, underpin the export of subsequent goods and services internationally."[95]

- ↑ Excluding trade with the rest of the United Kingdom.

The total value of international exports from Scotland in 2014 (excluding oil and gas) was estimated at £27.5 billion. The top five exporting industries in 2014 were food and drink (£4.8 billion), legal, accounting, management, architecture, engineering, technical testing and analysis activities (£2.3 billion), manufacture of refined petroleum and chemical products (£2.1 billion), mining and quarrying (£1.9 billion) and wholesale and retail trade (£1.8 billion). The total value of exports from Scotland to the rest of the UK in 2014 (excluding oil and gas) was estimated at £48.5 billion.[94]

Including all items Scotland, as the rest of the UK, runs a substantial trade deficit. In 2020 Scottish exports of goods and service including oil and gas totalled £78.4 billion in value while imports were worth £90.6 billion leaving Scotland with a trade deficit of £12.2 billion.[97]

Infrastructure

Transport

Ports

The primary airports in Scotland are: Edinburgh Airport, Glasgow International Airport, Glasgow Prestwick Airport, Aberdeen Airport, Inverness Airport and Dundee Airport. Most airports in Scotland were privatised in the 1980s. with the exception of those owned and operated by HIAL which operate airports in many islands which provide flights to mainland Scotland.

In 2004, 22.6 million passengers used Scotland's airports, with there being 514,000 aircraft movements[98] with Scottish airports being amongst the fastest growing in the United Kingdom in terms of passenger numbers. Plans have been published by the major airport operator BAA plc to facilitate the expansion of capacity at the major international airports of Aberdeen, Edinburgh and Glasgow, including new terminals and runways to cope with a large forecast rise in passenger use. Prestwick Airport also has large air freight operations and cargo handling facilities. Scotland is well-served by many airlines and has an expanding international route network, with long-haul services to Dubai, New York, Atlanta and Canada.

Additionally, Scotland has a number of seaports, including, Clydeport, Hunterston Ore Terminal, Grangemouth, Port of Dundee, Port of Aberdeen, and Port of Inverness however there are significant ports at Scapa Flow, Sullom Voe and Flotta. Grangemouth is the only port with a railway connection with W12 gauge clearance; allowing for intermodal containers to be transported by rail. The Greenock and Ayrshire railway railway tunnel underneath Greenock connecting Clydeport to the rail network is disused and its tunnels are too small for intermodal containers to be transported by rail. The Port of Aberdeen has a rail connection, but is unable to transport all types of intermodal containers.

Many island communities on Scotland's north and western seaboard are served by lifeline ferry services commissioned by the Scottish Government.[99] These ferry services are vital to island communities' economy by bringing in goods and tourists and in exporting textiles, whisky and other produce. These services usually and interface with the trunk road network on the Scottish mainland.

Trunk roads

.jpg.webp)

The trunk road network is a network of high-priority roads covering mainland Scotland, ensuring that all the major ports, population centres, and islands remain connected. These roads are maintained to a specified standard with traffic alerts published through Traffic Scotland in order to assist hauliers and are available on the Transport Scotland website. Trunk roads can be single-carriageway, dual carriageway or motorways and are not correlated to traffic volumes, but are determined on how significant the roads' closure would affect the local economy and supplies. With the exception to the M90 between Perth and western Edinburgh - a dual-carriageway road upgraded to motorway standard - all motorways in Scotland radiate outwards from Strathclyde.

Infrastructure in Scotland is varied in its provision and its quality. The densest network of roads and railways is concentrated in the Central Lowlands of the country where around 70% of the population live. The motorway and trunk road network is principally centred on the cities of Edinburgh and Glasgow and connecting them to other major concentrations of population, and is vitally important to the economy of Scotland. Key routes include the M8 motorway, which is one of the busiest and most important major routes in Scotland, with other primary routes such as the A9 connecting the Highlands to the Central Belt, and the A90/M90 connecting Edinburgh and Aberdeen in the east. The M74 and A1, in the west and east of the country, respectively, provide the main road corridors from Scotland to England. Many roads in the Highlands are single track, with passing places.

Railways

The Scottish railway networks were built in the Victorian era by private investors, primarily for the movement of goods, such as coal. In 1963, the UK Transport Minister Ernest Marples commissioned a review of the railway network which recommended closures in many places, which were adopted. A reprieve was earned by Liberal MPs in the Highlands who successfully argued that the skeletal railway network in the highlands was the only system which still functioned during periods of heavy snow when roads were blocked. These railways were kept open, however many uneconomic local railway services were closed as they had lost passenger traffic to the bus and the car, and goods traffic to road hauliers. Most railway services today are local passenger services in and around Glasgow, and intercity or regional passenger rail services as part of the ScotRail franchise, currently operated by Abellio. The Scottish Government also commissions the Caledonian Sleeper franchise, providing overnight sleeper services to London. Both cross-border mainline services are commissioned by the UK government on the West Coast Main Line and the East Coast Main Line. Most railways in Scotland are not electrified north of Central Belt rail, however there are plans to electrify the majority of railway lines.[100]

Local transport

The majority of transport infrastructure are local roads, maintained by Councils. Quality of local roads varies according to that Council's funding priorities. Bus services are private businesses operating commercially or under contract by the local Council. SPT operates the Glasgow Subway - a circular narrow-gauge railway disconnected from the rest of the railway network. The City of Edinburgh operates the Edinburgh Trams - the only light railway in Scotland. In many of the seven crofting counties, many roads are single-track with passing places. Drivers negotiate these passing places by pulling into the left - if the pulling place is to the driver's left, the on-coming vehicle has priority.

Communications

.jpg.webp)

Scotland is considered to have an advanced communications infrastructure, similar to other Western nations, and has an extensive framework of developed radio, television, landline and mobile phone, as well as broadband internet networks. As Scotland's landmass is immense, and the population sparse, the most populated areas have been focused on for 4G connection; mainly the Central Belt regions, Aberdeen, Dundee and Inverness.

Scotland's primary public broadcaster is BBC Scotland and operates a substantial number of television channels, including satellite channels, and numerous radio stations. Privately owned commercial TV and radio broadcasters operate a multitude national, regional and local channels.

Energy

Energy policy in Scotland is the responsibility of the UK government, however the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Government have used their devolved powers to influence energy policy in Scotland by controlling or preventing construction of new thermal power stations or encouraging construction of wind turbines. While matters such as preventing blackouts and regulated energy costs are UK government matters. Some matters are negotiated between the UK and Scottish Government such as the Beauly-Denny power line and other projects.

Electricity

The Energy Market is reserved by the UK government, with only the planning policy within the competency of the Scottish Parliament. Electricity Transmission infrastructure is split between two privately owned Distribution network operators; Scottish Power, and Scottish and Southern Energy and is regulated by OfGEM. In addition to the regulated utilities, private wires are also available. A very large proportion of energy is generated by wind, hydroelectric and nuclear sources. National Grid plc is the transmission system operator for the whole of the UK. Longannet power station - the last coal power station in Scotland - closed in 2016 earlier than anticipated following the reform of electricity connection charges.[101] Scotland has been identified as having significant potential for the development of wind power.

Scotland is endowed with some of the best renewable energy resources in Europe.[102] The Carbon intensity of the Scottish grid is among the lowest in Europe, at 44gCO2e/kWh[103][104]

In 2012 the Scottish Government set a target of 40% of Scotland's electricity generation be derived from renewable sources by 2020.[105] In Q1 2020, 90.1% of electricity was generated from renewable sources.[106] with onshore wind generation making the largest contribution, and supporting several thousand jobs. There are many windfarms along the coast and hills, with plans to create one of the world's largest onshore windfarms at Barvas Moor on the Hebridean Isle of Lewis.[107]

In 2022 Scotland exported a net 18.7 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity, 53% of the 35.2 TWh of renewable energy generated in 2022, worth £4 billion.[108] [109]

Gas

Gas infrastructure in Scotland is owned and operated by SGN and regulated by OfGEM. The UK is no longer self-sufficient with natural gas from the North Sea as the UK moved away from coal powered electricity stations. Gas is used across much of the UK for cooking and domestic heating - which also transitioned away from coal over the second half of the 20th century.

The Scottish Government plans to decarbonise the gas supply by 2030 by substituting natural gas with hydrogen.[110] As elemental hydrogen does not exist in nature on earth, Scottish energy policy intends that hydrogen be sourced from electrolysis powered by renewable energy and from steam-reformed methane with carbon capture and storage.[111]

Revenue from taxation

The majority of public sector revenue payable by Scottish residents and enterprises is collected at the UK level. Generally it is not possible to identify separately the proportion of revenue receivable from Scotland. GERS therefore uses a number of different methodologies to apportion revenue to Scotland. Following the implementation of the Scotland Act 2012 and Scotland Act 2016, an increasing amount of revenue is set to be devolved to the Scottish Parliament, whereby direct Scottish measures of these revenues will be available. The first revenues which have been devolved are landfill tax and property transaction taxes, with Scottish revenue collected for these taxes from 2015‑16 onwards.

With a nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of up to £152 billion in 2015, total public sector non-North Sea current revenue in Scotland was estimated to be £53.7 billion in 2015‑16 approx. 36.5% of GDP.[112] Current non-North Sea revenue in Scotland is estimated to have grown by 13.4% between 2011–12 and 2015–16 in nominal terms.[112] Total public sector expenditure for Scotland has been declining, as a share of GDP, since 2011–12, and in 2015-16 is estimated to be £68.6 billion which is around 46.6% FY2015-16.[112]

Labour market

As of March 2016, there were 348,045 Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) operating in Scotland, providing an estimated 1.2 million jobs. SMEs accounted for 99.3% of all private sector enterprises and for 54.6% of private sector employment and 40.5% of private sector turnover.[113] As of March 2016, there were an estimated 350,410 private sector enterprises operating in Scotland. Almost all of these enterprises (98.2%) were small (0 to 49 employees); 3,920 (1.1%) were medium-sized (50 to 249 employees) and 2,365(0.7%) were large (250 or more employees).[113]

Public sector

.gif)

The public sector, in Scotland, has a significant impact upon the economy and comprises central government departments, local government, and public corporations. As of 2016, there were approximately 545,000 people employed in the public sector, which accounts for 20.9% of employment in Scotland – this includes all medical professionals employed within the National Health Service in Scotland, those employed in the emergency services and those employed in the state education and higher education sector.[114] This is in addition to employees of the government in the civil service and in local government as well as public bodies and corporations. Public sector spending in Scotland was reported in 2017 to be more than £1,400 per head more than the UK average.[115]

Since the Devolution Referendum of 1997, in which the Scottish electorate voted for devolution, a Scottish Parliament was reconvened under the Scotland Act 1998 and is considered to be a devolved national, unicameral legislature of Scotland. The Act delineates the legislative competence of the Parliament – the areas in which it can make laws – by explicitly specifying powers that are "reserved" to the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Scottish Parliament has the power to legislate in all areas that are not explicitly reserved to Westminster. There is a clear separation of responsibility of the powers of both the UK government and the devolved Scottish Government in relation to the formulation and execution of national economic policy as it affects Scotland – this is set out under Section 5 of the Scotland Act 1998.

UK Government

The UK Government along with the Parliament of the United Kingdom retains control over Scotland's fiscal environment, in relation to taxation (including tax rates, tax collection, and tax criteria) and the overall share of central government expenditure apportioned to Scotland, in the form of an annual block grant.

Defence

There are several military bases within Scotland, as well as The Royal Scots' Battalion based in Bourlon Barracks, Yorkshire.

RAF Lossiemouth, RAF Kirknewton, RAF West Freugh

Kinloss Barracks, Redford Barracks, Dreghorn Barracks, Glencourse Barracks, Cameron Barracks, Forthside Barracks, Gordon Barracks, Walcheren Barracks

Social security

HM Treasury retains responsibility for the Welfare State. National Insurance rates and bands are reserved as is the National Insurance Fund. The State pension age is also reserved, as is the rate and eligibility of the UK State pensions system. HMRC are also responsible for calculating and paying Child Benefit and Working Tax Credit in addition to collecting Scottish income taxes.

The Department for Work and Pensions are responsible for determining eligibility criteria, processing and paying benefits and the development of Universal Credit. The Scottish Government has introduced the Scottish Welfare Fund[116] to lessen the impact of cuts to social security benefits.

Scottish Government

The Scottish Government has complete control over Scottish taxes collected by Revenue Scotland and has complete power to set tax rates and bands (but not the personal allowance) for income tax in Scotland which is collected by HMRC. It also provides the majority of local authority funding and can exert control over Council Tax - such as capping rates. The Scottish Government has full control over how Scotland's annual block grant is spent, such as healthcare, education and on state-owned enterprises, e.g. Scottish Water and Caledonian MacBrayne. The Scottish Government does not control macroeconomic policy, however it does use public procurement to influence private sector behaviour on reserved matters such as requiring the Real Living Wage[117] to be paid to all its contractors and sub-contractors. In 2016, the budget of the Scottish Government was around £37bn, which the Scottish Government can spend on the areas not reserved under the Scotland Act 1998.

Taxation

Taxes on fuel, motor vehicles, and Insurance, Corporation Tax, and VAT, are reserved to Westminster. The Scottish Government has the power to set tax rates and bands on income earned in Scotland. Income taxes are collected by HM Revenue & Customs on behalf of Scottish ministers and all revenues are paid into the Scottish Consolidated Fund.

The Scottish Parliament has full autonomy over Landfill Tax and Land and Buildings Transaction Tax the Scottish equivalent of Stamp Duty and is collected by Revenue Scotland. LBTT is a progressive tax, with different rates of tax paid on different bands of value. This differs to UK Stamp Duty, where only one rate of tax applies to the whole value of the property on a 'slab system' which distorted prices near thresholds between bands.

There are many aspects of Income Tax in Scotland which are reserved to Westminster, such as the setting of exemptions and allowances, most notably the personal allowance. The Scottish Parliament first diverged from UK tax policy in FY 2017-18 which increased the threshold for the higher rate of income tax(£43,000 as opposed to £45,000) following the Scotland Act 2016, which allowed rates and bands to be set with no reference to UK tax policy. The following financial year, two new bands were created; the Starter Rate, and the Intermediate Rate. The Additional Rate was renamed the Top Rate. Scottish taxpayers have an 'S' prefix to their PAYE code.

Divergence in income tax rates and bands mean that, for the 2023–2024 tax year, a person earning less than £27,850 in Scotland will pay less in income tax than a person with the same earnings in the rest of the UK, and a person earning more than £27,850 in Scotland will pay more in income tax than a person with the same earnings in the rest of the UK.[118][119] The higher and top rates are increased by 1% as of April 2023.

| Rate | Income tax rate | Gross income | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023–2024 | |||||

| Starter rate | 19% | £12,570[lower-alpha 1] – £14,732 | |||

| Basic rate | 20% | £14,733 – £25,688 | |||

| Intermediate rate | 21% | £25,689 – £43,632 | |||

| Higher rate | 42% | £43,633 – £125,140[lower-alpha 2] | |||

| Top rate | 47% | Above £125,140[lower-alpha 2] | |||

Economic development

The Scottish Government has several economic development agencies, with Highlands and Islands' Enterprise, Scottish Enterprise, and Scottish Development International. The Scottish Government recently established the Scottish National Investment Bank whose aim is to provide finance to small and medium-sized enterprises to grow and develop. Skills Development Scotland was also established to focus on workforce training, apprenticeships and industrial skills.

Local Government

Local government in Scotland currently consists of 32 Councils, which govern many aspects of daily life in Scotland, including:

- Bus stops (but not bus services)

- Care of vulnerable adults

- Children's social services

- Commissioning socially necessary bus services

- Community Transport (some)

- Council leisure centres and swimming baths - Arm's Length

- Council Tax

- Domestic refuse collection and disposal

- Food Hygiene inspections

- Licensing of hours of sale for alcohol

- Licensing of cultural music parades

- Licensing of taxis and private hire vehicles

- Licensing of window cleaners, market traders, scrap metal merchants, and street hawkers

- Licensing of sexual entertainment venues[120]

- Maintenance of all roads and pavements (except trunk roads which are the responsibility of Transport Scotland)

- Non-domestic rates †

- Nurseries

- Parking policy

- Primary and secondary schooling

- Public parks

- Regulation of landlords[121]

- Scottish Welfare Fund - administers

- Town and Country Planning

† Non-domestic rates in Scotland were previously collected by councils, pooled and redistributed to councils according to a set formula without any passing through central government funds with nationally set exemptions, rebates and other measures. This was abolished in 2020 and non-domestic rates are now entirely controlled by councils.[122]

Social housing

Scotland had some of the worst overcrowding in the postwar period and many areas of cities were comprehensively redeveloped with new modernist housing built either in tower blocks on the site of former slum housing, greenfield sites on the periphery of the cities, or in entirely new towns, such as Cumbernauld, Livingstone, Glenrothes or East Kilbride. Many former council houses are now run by Housing Associations while others were sold to the tenant under the right-to-buy at a heavy discount. Some of these have been sold on again and are now leased as private rental housing inside what was once a wholly council-owned housing scheme. The right to buy council housing was abolished in Scotland in 2017.[123][124]

Water and drainage

Water and sewerage utilities were never privatised in Scotland and were previously run by local water boards which were gradually amalgamated until in 2002 one national body was created; Scottish Water. Competition for retailing water to business customers was introduced in 2008. Unlike in England, water infrastructure remains property of Scottish Water, however metering and billing of business customers is now undertaken by water supply companies.[125] The water industry is regulated by the Water Industry Commission for Scotland. Scottish Water's retail company Business stream competes in the water retail market.

Council tax bills in Scotland still include water rates if the property has a water mains connection - it is important to note that some properties in rural areas are not connected to the mains network and have their own private water supply. Water for residential properties is not metered in Scotland.

Education

Scotland's public education system mostly follows comprehensive education principles, with two major types of public school; non-denominational schools, and denominational schools. Most denominational schools in Scotland are Roman Catholic. Public education in Scotland is more standardised than in England - Scotland has no equivalents of publicly funded grammar schools, free schools, nor academies except for Jordanhill School which is maintained by the Scottish Government through direct Grant-in-Aid. Scotland also has networks of private schools which are separate from the public schooling system. Confusion over the terminology can occur between Scotland and England as 'public schools' in England charge fees for educating pupils, whereas public schools in Scotland refer to local authority run schools. 'Public' schools in England offered their services openly (to the public) rather than running under the patronage of the Church. Council-run schools in Scotland were traditionally referred to as 'public schools' and many Victorian-era schoolhouses to this day have 'public' inscribed on their exterior. Terminology common to both systems are 'state schools' for publicly funded education and 'independent schools'.

Education in Scotland is 100% devolved and all of the universities in Scotland are public universities, as are the colleges which provide Further Education. Most universities are linked with a research and development sector; the University of Dundee is at the heart of a biotechnology and medical research cluster;[126] the University of Edinburgh is a centre of excellence in the field of Artificial Intelligence and the University of Aberdeen is a world-leader in the study of offshore technology in the oil and gas industry.[127]

Health

Another major component of public expenditure in Scotland is on medical and social care services delivered by the devolved National Health Service (NHS), which delivers the majority of medical services in Scotland, and Local Authorities responsible for social care services. NHS Scotland is a major employer with just under 140,000 whole-time equivalent (WTE) staff.[128] A further 150,000 WTE staff work in social care and services.[129] The NHS in Scotland began in 1948 under a separate Act from England and Wales and was the responsibility of the Secretary of State for Scotland rather than the Health Secretary before devolution. There is no healthcare purchaser-provider split in Scotland, and the abolition of internal market in NHS Scotland was completed in 2004.[130] The Cabinet Secretary for Health and Sport is now responsible for the NHS in Scotland.

The NHS and social care services are funded from Scottish taxation and the UK block grant and is an almost entirely devolved matter - with procurement of prescription medicines done on a UK-wide basis. Medical care is provided free at the point of use to patients registered with a GP Practice in Scotland. Scotland has a more generous social care system than England, with free personal nursing care for adults over 65[131] and those under 60 with certain medical conditions.[132] Scotland's more generous social care provision results in Scotland's per capita spending being 43% higher per capita than England.[133]

Prescribed drugs were made free at the point of use in 2011, leaving England as the only UK-nation with prescription charges in place (a flat fee of £9.35 per item[134]). Dental[135] and optometry[136] examinations are also free at the point of use, however charges for procedures and appliances apply for adults over 18, except in certain circumstances.

Per capital spending on medical and social care is the highest in Great Britain due to a more dispersed population and worse health inequalities with higher rates of alcohol dependency, alienation, drug addiction, suicide, and violence, which was dubbed 'the Glasgow effect' by the media.[137] Medical and social care spending is forecast to increase as the population is aging faster than in England.

Justice

The Scottish Legal system draws from the civil law tradition, and has more in common with civil law traditions such as in France, than the Common-Law of England and Wales. The Judiciary of Scotland run the Civil and Criminal courts and set court procedure through Acts of Sederunt, or Acts of Ajournal, respectively. Solicitors in Scotland are regulated by the Law Society of Scotland, rather than through the Solicitors Regulation Authority. Advocates are regulated by the Faculty of Advocates whereas in England and Wales; barristers are regulated by their Inn.

The criminal justice system is almost entirely devolved; including the Procurator Fiscal (the Scottish public prosecutor), the police force employing about 17,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff in 2019,[138] and HM prisons in Scotland which collectively imprison 8,500 people.[139] The most distinct differences in the Scottish criminal justice system is that only a simple majority of 15 is required to convict, the requirement for corroberation of evidence, and the existence of a third verdict. The Cabinet Secretary for Justice is responsible for policy matters affecting these systems such as legal aid, prison governance, drugs rehabilitation, reoffending, victims and witnesses, sentencing guidelines, and anti-social behaviour, but has a legal duty to uphold the independence of the courts and the legal profession. Following its creation from the merger of eight regional fire & rescue services, the Cabinet Secretary for Justice is also responsible for the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service.

The civil justice system also has many differences from England and Wales with many differences in Contract Law, Property Law, and Family Law. Scots law has 'Delict' rather than 'tort' law, and no legal concept of equity. 'Heritable title' is equivalent to a freehold in England and Wales, however there is no equivalent of a leasehold in Scots' law.

Regional economic performance

In Scotland, GDP per capita varies from €16,200 in North & East Ayrshire to €50,400 in Edinburgh city.[140] 1.1 million (20% of Scots) live in these five deprived [GDP per person is under €20,000] Scottish districts: Clackmannanshire & Fife, East & Mid Lothian, West Dumbartonshire, East & North Ayrshire, Caithness Sutherland & Ross.[140]

According to Eurostat figures (2013) there are huge regional disparities in the UK with GDP per capita ranging from €15,000 in West Wales to €179,800 in Inner-London West.[140] The average GDP per capita in the South East England region (excludes London) is €34,200 with no local government area showing a GDP per capita of less than €20,000.[140] Equally, there are 21 areas in the rest of the UK where the GDP per person is under €20,000: 4.5 million (8.5% of English) live in these deprived English districts.

The figures below, noting the economic position of Scottish regions in terms of GDP and GDP per capita, come from Eurostat (2013) and are denoted in Euros. It should also be noted that the Scottish figures exclude offshore oil revenue. There are 26 areas in the UK where the GDP per person is under €20,000.

| Area | Total € | Per capita € |

|---|---|---|

| Tayside | €13 bn | €25,950 |

| Angus & Dundee | €6.5 bn | €24,500 |

| Perth & Kinross & Stirling | €6.5 bn | €27,400 |

| Dumfries & Galloway | €3 bn | €20,500 |

| Scottish Borders | €2.3 bn | €20,300 |

| Clackmann. & Fife | €8.3 bn | €19,900 |

| Falkirk | €3.4 bn | €21,800 |

| Edinburgh & Lothian | €32.7 bn | €31,766 |

| Edinburgh | €24.6 bn | €50,400 |

| West Lothian | €4.6 bn | €26,200 |

| East & Mid Lothian | €3.5 bn | €18,700 |

| Glasgow & Strathclyde | €57.6 bn | €23,671 |

| Glasgow City | €25.5 bn | €42,700 |

| Inverclyde & East Renfrew & Renfrew | €7.3 bn | €21,000 |

| North Lanarkshire | €7.1 bn | €21,200 |

| South Ayrshire | €2.9 bn | €25,200 |

| South Lanarkshire | €6.7 bn | €21,500 |

| East & West Dumbarton | €4 bn | €17,900 |

| East & North Ayrshire | €4.1 bn | €16,200 |

| Grampian | €23.2 bn | €47,900 |

| Aberdeen & Aberdeensire | €23.2 bn | €47,900 |

| Highlands & Islands | €11.2 bn | €24,000 |

| Caithness & Sutherland & Ross & Cromarty | €1.7 bn | €18,400 |

| Inverness | €5.3 bn | €26,900 |

| Lochaber & Skye | €2.3 bn | €23,300 |

| Eilean Siar | €0.5 bn | €20,200 |

| Orkney | €0.5 bn | €23,600 |

| Shetland | €1.1 bn | €45,800 |

| Total | €154.9 bn | €29,100 (excl. oil revenue) |

Relationship with the rest of the United Kingdom

The Scottish Parliament has full control of Income tax, land taxes, property tax and local taxation and some fiscal policy. The Scottish Parliament also controls the areas of Health and Education policy. Other aspects of economic and fiscal policies remain a matter for Westminster - including currency, corporate tax, energy policy, foreign policy.

See also

- Barnett formula

- Council of Economic Advisers (Scotland)

- Economy of the United Kingdom

- Economy of England

- Economy of the European Union

- Full fiscal autonomy for Scotland

- Geography of Scotland

- Politics of Scotland

- Scottish Council for Development and Industry

- Scottish Enterprise

- 2014 Scottish independence referendum

- Starter for 6

- Sustainable Growth Commission

References

- ↑ "Edinburgh 4th in Europe in new Financial Centres index – Scottish Financial Review". Scottishfinancialreview.com.

- ↑ "Scotland's Census 2022 - Rounded population estimates". 14 September 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 "GDP Quarterly National Accounts, Scotland 2023 Quarter 2 (April to June)" (PDF). gov.scot. Scottish Government. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ↑ "Consumer price inflation, UK: December 2023". ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ↑ "UK". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ↑ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income - EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu/eurostat. Eurostat. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Scotland's Labour Market Trends : January 2024" (PDF). Gov.scot. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- 1 2 "Labour market in the regions of the UK: September 2023". ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ↑ "Public Sector Employment In Scotland Statistics For 1st Quarter 2022". Gov.scot. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ↑ "Ease of Doing Business in United Kingdom". Doingbusiness.org. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- ↑ "Export statistics Scotland: 2019". Gov.scot.

- ↑ "GDP Quarterly National Accounts for Scotland:2023 Q2". Gov.scot. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ↑ BBC (17 October 2012). "Scotland profile". BBC News. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ↑ "A survey of the liberalisation of public enterprises in the UK since 1979" (PDF). Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ "Acknowledgements" (PDF). Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Nigel Hawkins (1 November 2010). "Privatization Revisited" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Alan Griffiths & Stuart Wall (16 July 2011). "Applied Economics" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Nigel Hawkins (4 April 2008). "Privatization – Reviving the Momentum" (PDF). Adam Smith Institute, London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Graeme Hodge (28 October 2011). "Revisiting State and Market through Regulatory Governance: Observations of Privatisation, Partnerships, Politics and Performance" (PDF). Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ Chavez-Dreyfuss, Gertrude (1 April 2008). "Global reserves, dollar share up at end of 2007-IMF". Reuters. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- 1 2 "UK Employer Skills Survey 2022 – Scotland Report". The Scottish Government. Scottish Government. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- 1 2 Mackay Consultants (November 2007). The Economic Value of the House Building Industry in Scotland: a report for Homes For Scotland (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008.

- ↑ "Country and regional public sector finances expenditure tables - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ↑ "Statistics on Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland" (PDF). p. 5.

- ↑ "Scotland and the Caribbean" (PDF). National Museums Scotland. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ↑ "Equivalent Company". NatWest Group. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- 1 2 "The impact of union to 1715 Negative economic impact". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ↑ David Ross, A History of Scotland (2009) p 121/122

- ↑ "The impact of union to 1715 Positive economic impact". BBC Bitesize. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ↑ David McCrone, Understanding Scotland: the sociology of a nation (2001) p 56

- ↑ Arthur L. Herman, How the Scots Invented the Modern World: The True Story of How Western Europe's Poorest Nation Created Our World & Everything in It(2001)

- ↑ Bruce Lenman, An Economic History of Modern Scotland, 1660–1976 (1977)

- ↑ Catriona M. M. MacDonald, and E. W. McFarland, Scotland and the Great War (1999)

- ↑ "Scotland's economy recovering but fragile". Gov.scot.

- 1 2 "Tourism Recovery Recommendations". Scottishtourismallaince.co.uk. 23 October 2020. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

discussions led by Malcolm Roughead, CEO, VisitScotland, Marc Crothall, CEO, Scottish Tourism Alliance and Malcolm Buchanan, Chair of Scotland Board, RBS

- ↑ "£25 million for tourism recovery". Gov.scot. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

We've provided an unprecedented amount of funding for the sector, including over £129 million in business support

- ↑ "Coronavirus 'could hit Scottish economy as hard as the loss of heavy industry'". Insider.co.uk. 10 November 2020.

- ↑ "Data shows collapse of UK food and drink exports post-Brexit". TheGuardian.com. 22 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ↑ "Scotland's whisky islands are dealing with a major Covid hangover". CNN. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ↑ "COVID COSTS SCOTCH WHISKY EXPORTS £1.1 BILLION IN LOST SALES". Scottishfield.co.uk. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ↑ "Scotch whisky exports slump to 'lowest in a decade'". BBC News. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ↑ "Explaining the rise in price of Scottish arable land | Strutt & Parker". Struttandparker.com.

- ↑ "Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003". Office of Public Sector Information. 2003. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- ↑ "Scotland's Forestry Strategy 2019–2029". Gov.scot.

- ↑ "Fisheries Research Services The Changing Abundance of Spring Salmon" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2012.

- ↑ "Longannet power station closes ending coal power use in Scotland". The Guardian. 24 March 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ↑ "Fracking". Foe.scot. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ↑ "Scotland announces moratorium on fracking for shale gas". The Guardian. 28 January 2015.

- ↑ Shepherd, Mike (2015). Oil Strike North Sea: A first-hand history of North Sea oil. Luath Press.

- ↑ "Scottish Marine Bill Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA): Environmental Report (ER)". The Scottish Government. p. 28. Archived from the original on 2 February 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ↑ "Oil and gas research and information". Scottish Enterprise. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009.

- ↑ Hopes of Western Isles bonanza as Shell starts searching for oil The Times December 2005

- ↑ "Oil and gas industry 'worth £35bn annually' to UK economy". BBC News. 23 April 2014.

- ↑ Lynch, Michael (1992). Scotland: A New History. Pimlico. p. 408. ISBN 0-7126-9893-0.

- ↑ Fraser, W. Hamish (2004). "Second City of The Empire: 1830s to 1914". The Glasgow Story. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- ↑ "Industrial decline – the 20th Century". Glasgow City Council. 28 March 2008. Archived from the original on 3 July 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2009.

- ↑ Scotch Whisky Association. "Scotch Whisky Exports Hit Record Level". Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Scotch Whisky Association. "Scotch Whisky Briefing 2013". Archived from the original on 7 May 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ The Whisky Barrel (11 September 2011). "Scotch Whisky Exports & Visitor Numbers Soar". Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Lynch, Michael (1992). Scotland: A New History. Pimlico. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-7126-9893-0.

- ↑ "The Scottish Staple at Veere". Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ↑ "Museum De Schotse Huizen". Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ↑ "Letter of five Scots to Gdansk City Council with request for citizenship, dated 1594". Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2009.

- ↑ Lynch, p381.

- ↑ Michael Meighan, Glasgow: A History (Amberley Publishing, 2013), p. 47.

- ↑ Lynch, p382-3

- ↑ Anthony Cooke, The Rise and Fall of the Scottish Cotton Industry, 1778-1914 (Manchester University Press, 2010), p. 30.

- ↑ "Scottish Enterprise – Textile Industry, Facts and Figures". Archived from the original on 22 March 2006.

- ↑ "Key Facts and Figures on the Electronics Industry from Scottish Enterprise". Archived from the original on 22 March 2006.

- ↑ "Number of new homes built in Scotland up 15% year on year". Propertywire.com. 12 June 2019.

- ↑ Askeland, Erikka (20 March 2012) "Scots Cities Slide down Chart of the World's Top Financial Centres". The Scotsman.

- ↑ "The Global Financial Centres Index 18". (September 2015) p. 5. Long Finance.

- ↑ "Scottish Financial Enterprise Industry Overview". Archived from the original on 22 December 2005.

- ↑ "Financial services". Scottish Enterprise. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ↑ "GFCI 27 Rank - Long Finance". Longfinance.net. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ↑ "TSB". Lloyds TSB. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ↑ "RBS collapse: timeline". The Guardian. London. 12 December 2011.

- ↑ "Scottish Financial Enterprise – Financial Industry Overview". Archived from the original on 6 May 2006.

- ↑ "Lloyds Bank - Internet Banking - Error". Lloydsbank.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2012.

- ↑ "Parliamentary Business : Scottish Parliament" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2009.

- ↑ "A history of life as we know it". The Scotsman. 21 February 2002. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ↑ Stevenson, Rachel (6 April 2004). "Standard Life, last of the Scottish mutuals, presides over Edinburgh's changing scene". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ↑ Fry, Michael (2001). The Scottish Empire. Tuckwell Press. p. 270. ISBN 1-84158-259-X.

- ↑ Fry, p. 269

- ↑ "Overview of the Scottish Financial Industry". Archived from the original on 6 May 2006.